Abstract

A new complex, [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN)]2+ (1, tpy = 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine, dppn = benzo[i]dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine) was synthesized and its photochemical properties were investigated. This complex undergoes photorelease of the Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN ligand, a known cathepsin K inhibitor, with a quantum yield, Φ450, of 0.0012(4) in water (λirr = 450 nm). In addition, 1 sensitizes the production of singlet oxygen upon visible light irradiation with quantum yield, ΦΔ, of 0.64(3) in CH3OH. The photophysical properties of 1 were compared with those of [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN)]2+ (2, bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine), [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(CH3CN)]2+ (3), and [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(CH3CN)]2+ (4) to evaluate the effect of the release of the Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN inhibitor relative to the CH3CN ligand, as well as the role of dppn as the bidentate ligand for 1O2 production instead of bpy. Nanosecond transient absorption spectroscopy confirms the formation of the long-lived dppn-centered 3ππ* state in 1 and 3 with a maximum at ∼540 nm and τ ∼20 μs in deaerated acetonitrile. Complexes 1 and 3 are able to cause photoinduced damage to DNA (λirr ≥ 395 nm), whereas 2 and 4 do not cause DNA photocleavage under similar experimental conditions. These results suggest that 1 is a promising agent for dual activity, both releasing a drug and producing singlet oxygen, and is poised to exhibit enhanced biological activity in phototochemotherapy upon irradiation with visible light.

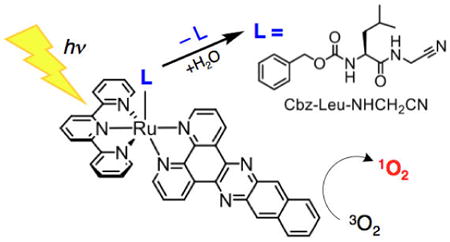

Graphical abstract

Synopsis. A new Ru(II) complex releases a cysteine protease inhibitor and produces cytotoxic 1O2 upon irradiation with visible light, making it potentially useful as a dual-action PDT agent.

Introduction

The spatiotemporal control over therapeutic activity that photodynamic therapy (PDT) provides is attractive in the development of cancer treatment methods that are less invasive and present fewer side effects than surgical resection or chemotherapy.1–5 Traditional PDT requires ground state 3O2, a photosensitizer with a long excited state lifetime, and activation using low energy visible light, preferably in the therapeutic window of 600 – 900 nm.6–8 For optimal performance, the photosensitizer should be inactive in the dark, but able to transfer energy from its excited state to 3O2 to form cytotoxic 1O2 upon irradiation, such that the therapeutic activity of PDT agents occurs only in tissue that is exposed to light.1–8 Photofrin, a mixture of hematoporphyrin and its oligomers, was approved in the U.S. as a PDT agent in 1995 for the treatment of head, neck, and esophageal cancers.9 Photofrin absorbs strongly in the therapeutic window due to the Q-band porphyrin transitions, leading to the population of the long-lived 3ππ* excited state with a quantum yield of 0.83; the latter sensitizes the production of 1O2 with quantum yields, ΦΔ, of 0.65 in methanol and 0.74 in water at pH 7.4.9 One drawback of Photofrin is its inability to enter cells, such that 1O2 production results in necrosis, making treatment painful to the patient.10 Instead, small cationic transition metal complexes possessing ligands with extended π-systems were shown to produce 1O2 in high yield, enter cancer cells, and promote apoptosis upon irradiation.11

Ru(II) diimine complexes represent one class of molecules with extremely high quantum yields of 1O2 production owing to their ∼100% yield of intersystem crossing to long-lived triplet metal-to-ligand charge transfer (3MLCT) excited states.12,13 For example, [Ru(bpy)3]2+ (bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine), [Ru(bpy)2(dppn)]2+ (dppn = benzo[i]-dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine), and [Ru(bpy)2(ippy)]2+ (ippy = 2-(1-pyrenyl)-1H-imidazo[4,5-f][1,10]-phenanthroline) produce 1O2 with ΦΔ =0.81, 0.88, and 0.73, respectively.14,15,16 Although these complexes produce 1O2 in high yields, the reliance of the action of the drug on the presecne of O2 represents a limitation for treatment for hypoxic tumors.9,17

To overcome the limitations of traditional PDT agents in the treatment of hypoxic tumors, Ru(II)-diimine complexes that undergo light-induced ligand exchange to deliver a biologically active compound have been a subject of intense investigation.18–22 These potential PDT agents can function either by labilization of a metal-ligand bond to allow for covalent binding of the metal center to biomolecules, such as DNA, or by the release of a caged drug coordinated to the metal center.18–22,23 Photoinduced ligand exchange in Ru(II) complexes is generally believed to take place via the thermal population of metal-centered 3LF (ligand field) state(s) from the lowest energy 3MLCT (metal-to-ligand charge transfer) state, which places electron density on Ru–L orbitals with σ* antibonding character.25,26 Complexes of the type[Ru(bpy)2(L)2]2+ (L = CH3CN, pyridine, NH3) and [Ru(bpy)2(L′)]2+ (L′ = 6,6′-dimethyl-2,2′-bipyridine,7,10-dimethylpyrazino[2,3-f][1,10]phenanthroline) have been reported to exchange the monodentate L or bidentate L′ ligands with solvent molecules upon visible light irradiation,27 and the resulting [Ru(bpy)2(OH2)2]2+ moiety was shown to covalently bind to DNA in a manner akin to cisplatin.18c,28

In addition to these systems, photoinduced ligand release can be used to achieve spatiotemporal control over caged drug delivery. For example, [Ru(bpy)2(5CNU)2]2+ (5CNU = 5-cyanouracil)28a and [Ru(tpy)(5CNU)3]2+ were shown to release the cytotoxic 5CNU ligand upon irradiation,29 and Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes have also been used to photorelease peptides that inhibit enzymes that promote metastasis and are overexpressed in cancer cells.20,30,31 Recently, [Ru(bpy)2(PPh3)(RGH)]2+ (RGH = tripeptide Arg-Gly-His) was reported to release the bioactive RGH tripeptide upon irradiation.31 Similarly, complexes of the [Ru(bpy)2(peptide-CN)2]2+ architecture, where peptide-CN = Ac-Phe-NHCH2CN, Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN, Cbz-Leu-Ser(OBn)-CN, were reported to release enzyme inhibiting peptides upon irradiation, leading to cell death.30 Other examples of bioactive molecules released from Ru(II) cages upon irradiation include cytochrome p450 inhibitors, such as metyrapone and etomidate.18a,20b

In order to increase the efficiency of PDT agents, complexes that are able to achieve cell death via multiple modes of action are being investigated. For example, [Ru(bpy)(dppn)(CH3CN)2]2+ combines the production of 1O2 with photorelease of the CH3CN ligands, and the metal-containing product is able to covalently bind to DNA.32 The dual activity by this complex results in ∼1100 fold increase in toxicity upon irradiation as compared to dark activity, which represents an ∼170-fold increase in reactivity compared to than that of the related complex [Ru(bpy)2(CH3CN)2]2+, which only exchanges ligands, and ∼4 fold greater than [Ru(bpy)2(dppn)]2+ which is only able to produce 1O2. Additionally, [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)(py)]2+ (Me2dppn = 3,6-dimethylbenzo[i]dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine) and [Ru(pydppn)(biq)(py)]2+ (pydppn = 3-(pyridin-2-yl)benzo[i]dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine, biq= 2,2′-biquinoline) have shown potential as dual action PDT agents due to the ability to produce 1O2 and undergo photoinduced exchange of the pyridine ligand with a solvent molecule.33

The work reported herein focuses on the combination of 1O2 production and the release of a caged bioactive molecule upon irradiation with visible light by complexes with a [Ru(tpy)(L′)(L)]2+ architecture, where L′ = bpy or dppn and L = CH3CN or Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN (Figure 1). [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN)]2+(1) produces 1O2 and releases Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN, a known cathepsin K inhibitor, whereas [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN)]2+ (2) is only able to undergo the release of the Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN ligand. Two additional control complexes were also investigated, [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(CH3CN)]2+ (3), which only produces 1O2, and [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(CH3CN)]2+ (4), which neither sensitizes the production of 1O2 nor releases a nitrile drug upon irradiation. These controls were designed to gain further understanding of the impact of the [Ru(tpy)(L′)(OH2)]2+ complex after release of Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN, since complexes 1 and 3 result in the same photoproduct, [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(OH2)]2+ (5), and complexes 2 and 4 result in the same photoproduct, [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(OH2)]2+ (6), upon irradiation with visible light in water. Cathepsin K is a protease that is overexpressed in various cancers and is associated with promoting metastasis.34 Dual mode complexes that release protease inhibitors and generate 1O2 have potential applications in cancer treatment because they generate 1O2 to kill tumor cells and reduce metastasis through cathepsin K inhibition.

Figure 1.

Schematic representations of the structures of 1 – 4.

Experimental Section

Materials

All materials were used as received without further purification unless otherwise noted. Ethanol (200 proof) was purchased from Decon Laboratories, diethyl ether, acetone, acetonitrile, and methanol were procured from Fisher Scientific, and dichloromethane and hexanes were obtained from Macron Fine Chemicals. N,N-dimethylformamide was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and was vacuumed distilled to dryness. Ammonium hexafluorophosphate, lithium chloride, potassium chloride, silver tetrafluoroborate, silver trifluoromethanesulfonate, 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine (tpy), 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF), methylene chloride-d2 and acetone-d6 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and 2,2′-bipyridine was obtained from Alfa Aesar. Triethylamine and sodium bicarbonate were received from Fisher Scientific, and potassium ferrioxoalate was purchased from Strem Chemicals. Neutral alumina, purchased from Fisher Scientific, was deactivated with methanol. The pUC19 plasmid was purchased from Bayou Biolabs and purified via the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Spin system purchased from Qiagen, and the SmaI restriction enzyme was purchased from Invitrogen Life Technology. The complexes Ru(tpy)Cl3, [Ru(tpy)(bpy)Cl](PF6), [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(CH3CN)](PF6)2, [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(py)](PF6)2, [Ru(bpy)2(dppn)](PF6)2, dppn, and Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN were synthesized according to published procedures.33a,35–39 The aqua complexes [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(OH2)](PF6)2 (5) and [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(OH2)](PF6)2 (6) were obtained by irradiating solutions of 0.5 mM [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(CH3CN)](PF6)2 and 1.0 mM [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(CH3CN)](PF6)2, respectively, in water (<5% acetone) under a nitrogen atmosphere with λirr > 395 nm until conversion was completed.

[Ru(tpy)(dppn)Cl](PF6) was prepared by refluxing a mixture of Ru(tpy)Cl3 (100 mg, 0.227 mmol), dppn (110 mg, 0.331 mmol), LiCl (120 mg, 2.83 mmol) and triethylamine (250 μL, 1.79 mmol) in 25 mL of EtOH for 4 hours under a nitrogen atmosphere. The purple reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and stirred with aqueous NH4PF6. The EtOH was removed under a gentle stream of N2, and the precipitate was collected by vacuum filtration and washed with H2O, acetone, and toluene. Purification was achieved by first dissolving the resulting solid in CH2Cl2 and removing the remaining solid by centrifugation. The complex was isolated by column chromatography using a deactivated alumina stationary phase with a CH2Cl2 (1% MeOH) mobile phase. A yellow band containing excess dppn eluted first, followed by a purple band containing the desired product. Solvent was removed by rotary evaporation resulting in 80 mg of dark purple product (0.094 mmol, 42% yield). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2) δ ppm 7.23 (t, 1H), 7.23 (dd, 1H), 7.52 (dd, 1H), 7.71 (m, 3H), 7.78 (m, 2H), 7.90 (td, 2H), 8.20 (t, 1H), 8.34 (m, 4H), 8.45 (dd, 1H), 8.48 (d, 2H), 9.11 (s, 1H), 9.21 (s, 1H), 9.43 (dd, 1H), 9.98 (dd, 1H), 10.68 (dd, 1H). ESI MS:[M–PF6]+ experimental m/z = 702.11, calculated m/z = 702.07.

[Ru(tpy)(dppn)(Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN)](PF6)2 ([1](PF6)2)

[Ru(tpy)(dppn)(Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN)](PF6)2 was prepared by refluxing a mixture of [Ru(tpy)(dppn)Cl](PF6) (55 mg, 0.065 mmol), Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN (165 mg, 0.544 mmol) and AgBF4 (62 mg, 0.32 mmol) in 20 mL of EtOH for 20 hours under a nitrogen atmosphere and shielded from room light with aluminum foil. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and filtered through Celite to remove insoluble impurities. The filtrate was added dropwise to a solution of aqueous NH4PF6 and the resulting orange precipitate was collected by vacuum filtration. The solid was dissolved in a minimal amount of acetone then added dropwise to stirring diethyl ether; the precipitate was collected by vacuum filtration resulting in 65 mg of product (0.052 mmol, 79% yield). 1H NMR ((CD3)2CO) δ 1.25 ppm (s, 1H), 1.51 (m, 3H), 1.66 (m, 1H), 2.66 (m, 1H), 2.80 (m, 4H), 4.08 (m, 1H), 4.33 (d, 2H), 5.00 (dd, 2H), 6.62 (d, 1H), 7.30 (s, 5H), 7.40 (t, 2H), 7.68 (m, 3H), 7.97 (t, 1H), 8.01 (t, 2H), 8.07 (dd, 1H), 8.11 (t, 2H), 8.33 (m, 2H), 8.50 (t, 1H), 8.57 (dd, 1H), 8.72 (d, 2H), 8.88 (d, 2H), 9.04 (s, 1H), 9.13 (s, 1H), 9.40 (dd, 1H), 9.92 (dd, 1H), 10.28 (dd, 1H). ESI MS: [M–2PF6]2+ experimental m/z = 485.12, calculated m/z = 485.13. Anal. Calc for C53H44F12N10O3P2Ru•(CH3)2CO•H2O: C, 50.34; H, 3.92; N, 10.48. Found C, 49.92; H, 3.87; N, 10.48.

[Ru(tpy)(bpy)(Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN)](PF6)2 ([2](PF6)2)

[Ru(tpy)(bpy)(Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN)](PF6)2 was prepared by combining [Ru(tpy)(bpy)Cl](PF6) (32 mg, 0.048 mmol), Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN (80 mg, 0.26 mmol), and AgBF4 (28 mg, 0.14 mmol) in 15 mL of EtOH bubbled with N2. The solution was refluxed overnight under a nitrogen atmosphere, while shielded from light with aluminum foil. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature then further cooled in an ice bath and filtered through Celite to remove solid impurities. The filtrate was added dropwise to a solution of aqueous NH4PF6 and the resulting orange precipitate was collected by vacuum filtration. Excess ligand was removed by dissolving solid in acetone followed by centrifugation. The acetone solution was then added dropwise into stirring diethyl ether, and the precipitate was collected by vacuum filtration yielding 28 mg (0.026 mmol, 54% yield). 1H NMR ((CD3)2CO) δ 0.23 ppm (t, 2H), 0.40 (s, 2H), 0.58 (m, 2H), 0.73 (m, 2H), 2.68 (q, 1H), 3.16 (m, 1H), 3.32 (d, 1H), 3.38 (d, 1H), 4.14 (q, 2H), 5.73 (d, 1H) 6.36 (td, 1H), 6.46 (s, 5H), 6.62 (td, 3H), 6.76 (dt, 1H), 7.15 (m, 6H), 7.56 (m, 2H), 7.79 (t, 2H), 7.97 (d, 2H), 8.03 (d, 1H), 8.98 (d, 1H). ESI MS: [M–2PF6]2+ experimental m/z = 397.11, calculated m/z = 397.12. Anal. Calc for C41H40F12N8O3P2Ru•2(CH3)2CO: C, 47.04; H, 4.37; N, 9.34. Found C, 47.00; H, 4.43; N, 9.30.

[Ru(tpy)(dppn)(CH3CN)](PF6)2 ([3](PF6)2)

[Ru(tpy)(dppn)(CH3CN)](PF6)2 was prepared by refluxing a mixture of [Ru(tpy)(dppn)Cl](PF6) (30 mg, 0.035 mmol) in 15 mL of 1:1 CH3CN:H2O (v/v) overnight under a nitrogen atmosphere, while shielded from light with aluminum foil. The reaction was cooled to room temperature, excess NH4PF6 was added, and the solution was stirred for 30 minutes. The orange precipitate was collected by vacuum filtration and washed with H2O resulting in 15 mg (0.015 mmol, 43% yield). 1H NMR ((CD3)2CO) δ 2.43 ppm (s, 3H), 7.45 (m, 2H), 7.76 (m, 1H), 7.80 (m, 2H), 8.09 (d, 2H), 8.16 (m, 3H), 8.44 (m, 2H), 8.58 (t, 1H) 8.63 (q, 1H), 8.81 (dt, 2H), 8.97 (dd, 2H), 9.15 (s, 1H), 9.25 (s, 1H). 9.52 (dd, 1H), 10.03 (dd, 1H), 10.35 (dd, 1H). ESI MS: [M–2PF6]2+ experimental m/z = 354.06, calculated m/z = 354.07. Anal. Calc for C39H26F12N8P2Ru•H2O: C, 46.12; H, 2.78; N, 11.03. Found C, 46.29; H, 2.72; N, 10.80.

Instrumentation and Methods

1H NMR spectra were collected with a Bruker 400 MHz DPX spectrometer. The sample was dissolved in acetone-d6 or methylene chloride-d2, syringe filtered to remove any solid, and the chemical shifts were referenced the residual solvent peak (2.05 ppm or 5.32 ppm). Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) was performed with a Bruker micrOTOF instrument dissolved in methanol. Elemental analysis was performed at the CENTC Elemental Analysis Facility at the University of Rochester (Rochester, NY). Electronic absorption spectra were obtained using a Hewlett-Packard 8453 diode array spectrophotometer and luminescence was measured using a Horiba Fluoromax-4 spectrometer in 1×1 cm quartz cuvettes. Extinction coefficients were determined in triplicate and reported as the average value with the error as one standard deviation. Sample irradiation was performed using a 150 W Xe arc lamp (USHIO) in a MilliArc lamp housing unit with an LPS-220 power supply and an LPS-221 igniter (PTI). The desired irradiation wavelengths were controlled by selecting the appropriate long pass (CVI Melles Griot) or bandpass (Thorlabs) filters. In general, the samples were irradiated in water (<5% acetone) in a quartz cuvette, and a 395 nm long pass filter placed between the arc lamp and the sample holder. Electronic absorption spectra were recorded at various time points throughout the photolysis. The ligand exchange quantum yields (ΦL) were determined by irradiating the samples (concentration ranging from 35 μM to 70 μM) in water using a 450 nm band pass filter together with a 395 nm long pass filter to ensure that no high energy light reached the sample. The electronic absorption spectra were recorded at early irradiation times (<10% conversion), and the rate of consumption of the reactant was determined from the slope of the line of a plot of the moles of reactant vs irradiation time. The photon flux of the lamp was determined to be 2.4(1) × 10−7 Einsteins/min using potassium ferrioxalate as the chemical actinometer.40 The quantum yield for ligand dissociation using 450 nm light (ΦL) was calculated as the rate of moles of reactant consumed divided by the photon flux and corrected for the mean fraction of light (fm) absorbed by the sample, see Equation S1 and Equation S2. The quantum yields for 1O2 production (ΦΔ) were measured using [Ru(bpy)3]2+ as a standard, with ΦΔ = 0.81 in CH3OH,41 and 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF) as a 1O2 trap. DPBF is emissive in CH3OH, and the resulting product from the reaction of DPBF with 1O2 is nonemissive. The absorbance values of samples in methanol were matched at the irradiation wavelength (A = 0.01 at 460 nm) in a 1×1 cm quartz cuvette. The samples were irradiated in the sample compartment of the fluorimeter (λirr = 460 nm) in the presence of 1.0 μM DPBF, and the quenching of the DPBF emission (λexc = 405 nm; λem = 479 nm) was monitored as a function of irradiation time, resulting in a linear plot of the emission intensity vs irradiation time, and the quantum yield was determined by comparing the slope for the sample with that obtained for the [Ru(bpy)3]2+ standard. DNA photocleavage experiments were carried out with 20 μL total volume in transparent 0.5 mL Eppendorf tubes containing 100 μM pUC19 plasmid (concentration in bases), 10 or 20μM of each complex, and 5 mM Tris buffer (pH = 7.5, 50 mM NaCl) in water. After incubation for 30 minutes in the dark at room temperature, the samples were irradiated with a 150 W Xe arc lamp (λirr ≥ 395 mn). After irradiation, 4 μL of loading dye buffer was added to each sample and the solutions were loaded into a 1% agarose gel (stained with 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide) in a 1× TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA, pH ∼8.5). Gel electrophoresis was performed at a voltage of 60 V for ∼1.5 hours; different conditions are described as needed. The gels were imaged using a BioRad Gel Doc 2000 transilluminator. For nanosecond transient absorption (nsTA) experiments, the excitation source was an optical parametric oscillator (basiScan, Spectra-Physics), pumped by a Nd:YAG laser (Quanta-Ray INDI, Spectra-Physics), with ca. 6 ns at a repetition frequency of 10 Hz. The spectrometer (LP980, Edinburgh Instruments) used a continuous 150 W xenon arc lamp as probe source. The spectral measurements were collected with an ICCD camera while the kinetic traces were measured with a PMT and a digital oscilloscope. Samples for nsTA were prepared in a 1×1 cm quartz cuvette with an absorbance vale of 0.5 OD at the excitation wavelength.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Electronic Absorption Spectroscopy

Complex 1 was designed to both release the active Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN cathepsin K inhibitor and to produce cytotoxic 1O2 with high efficiency upon irradiation with visible light, generating [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(OH2)]2+ (5) upon photoinduced ligand exchange in aqueous media. The sensitized production of 1O2 is not expected to take place in 2 because it lacks the extended π-system of dppn, but it should be able to release the caged inhibitor when irradiated resulting the formation of [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(OH2)]2+. Additionally, the two corresponding CH3CN complexes were prepared, 3 and 4, as analogs that cannot release the caged drugs, however, their photoinduced ligand exchange in water also results in the formation of 5 and [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(OH2)]2+ (6), respectively. Moreover, 3 possesses the capability to produce 1O2, but will serve as a control for 1 because it does not release a biologically active molecule.

Complexes 1 – 4 were prepared by reacting the desired bidentate L′ ligand, bpy or dppn, with Ru(tpy)Cl3 in the presence of excess chloride and the reducing agent triethylamine to produce the corresponding [Ru(tpy)(L′)Cl]+ complexes. The inner-sphere chloride anion was replaced with CH3CN by refluxing [Ru(tpy)(L′)Cl]+(L′ = bpy, dppn) in CH3CN/H2O (1:1, v:v) to generate the corresponding [Ru(tpy)(L′)(CH3CN)]2+ complex, while refluxing each reactant in EtOH with excess Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN resulted in [Ru(tpy)(L′)(Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN)]2+ (L′ = bpy, dppn). The samples were characterized by 1H NMR, and the ESI-MS for each complex exhibits molecular ion peaks corresponding to the divalent [M] – 2PF6 parent ion, where [M] = 1 – 4 (Figure S1 and S2).

The Ru(II) complexes 1 – 4 absorb ultraviolet and visible light efficiently, extending to ∼600 nm at low energies. The electronic absorption spectra of 1 – 4 collected in CH3CN are shown in Figure S3, and the 1MLCT absorption maxima and extinction coefficients are listed in Table 1. The Ru→tpy/bpy 1MLCT transitions are observed at 455 nm (ε = 9,700 M−1cm−1) and 454 nm (ε = 10,400 M−1cm−1) for 2 and 4 in acetone, respectively. The similarity in absorption maxima and extinction coefficients demonstrates that the substituents on the nitrile ligand have a negligible impact on the 1MLCT transition. Similarly to the analogous bpy complexes, the Ru→tpy/dppn 1MLCT transitions of 1 and 3 are observed at 455 nm with ε = 16,800 M–1cm−1 and 15,700 M−1cm−1 respectively. The enhanced extinction coefficients of the dppn complexes as compared to their bpy counterparts are likely due to contributions from overlapping dppn-centered 1ππ* transitions with maxima at 385 nm and 407 nm; these peaks exhibit ε values of 14,000 M−1cm−1 and 16,400 M−1cm−1 in 1, respectively, and of 12,600 M−1cm−1 and 14,700 M−1cm−1 in 3, respectively. The enhancement of the extinction coefficient is similar to that reported in related systems such as [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(py)]2+ as compared to [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(py)]2+, with molar absorptivities of 12,900 M−1cm−1 at 474 nm for the former and 8,120 M−1cm−1 at 468 nm for the latter.33a

Table 1.

1MLCT Absorption Maxima, λabs, and Molar Extinction Coefficients, ε, in Acetone, Quantum Yield of Photoinduced Ligand Exchange in H2O, ΦL, and Quantum Yield of 1O2 Production, ΦΔ, for 1 – 4.

| Complex | λabs/nm (ε/M−1cm−1) | ΦL | ΦΔ |

|---|---|---|---|

| [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN)]2+ (1) | 455 (16,800) | 0.00014(3) | 0.64(3) |

| [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN)]2+ (2) | 455 (9,700) | 0.0012(4) | |

| [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(CH3CN)]2+ (3) | 455 (15,700) | 0.00023(1) | 0.67(6) |

| [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(CH3CN)]2+ (4) | 454 (10,400) | 0.0026(2) |

Photochemistry in Solution

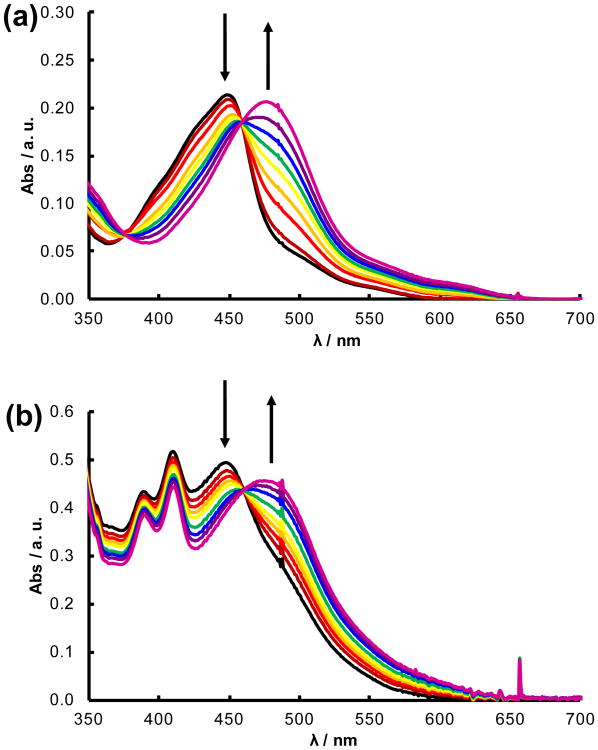

Upon irradiation with visible light, the monodentate nitrile ligand, Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN in 1 and 2 or CH3CN in 3 and 4, is replaced by a solvent H2O molecule to produce the corresponding [Ru(tpy)(L′)(OH2)]2+ (L′ = bpy, dppn) photoproduct. For example, the changes in the electronic absorption spectrum of 2 as a function of irradiation time (0 – 80 min) are shown in Figure 2a (λirr ≥ 395 nm), which result in a red shift in the 1MLCT transition from 455 nm to 478 nm with isosbestic points at 376 and 459 nm. The absorption of the photoproduct is consistent with that previously reported for [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(OH2)]2+, formed following the exchange of Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN for a solvent H2O molecule.35b In addition, the spectral changes observed upon irradiation are in agreement with those of 4 (Figure S4a), which generates the same product upon solvolysis. This process for 2 occurs with a quantum yield (ΦL, λirr = 450 nm) of 0.0012(4), a value lower than that measured for 4, ΦL = 0.0026(2). The difference in efficiency is attributed to the lower solubility and size of the peptide ligand compared to CH3CN in water, making the escape from the solvent cage less probable in 4 than in 2, such that the regeneration of the starting material is more likely in the former.42

Figure 2.

Changes to the electronic absorption spectra upon irradiation (λirr ≥ 395 nm) of (a) 2 for 0 – 80 min and (b) 1 for 0 – 180 minin water (< 5% acetone; bubbled with N2 for 10 min).

The photoinduced ligand exchange of 1 was monitored in water deoxygenated by bubbling with N2 for 10 min to prevent the formation of 1O2 (Figure 2b). As the sample was irradiated, the 1MLCT transition red shifted from 448 nm to 477 nm with an isosbestic point at 460 nm. A small decrease of the dppn 1ππ* absorption bands at 389 and 410 nm was observed attributed to the bathochromic shift of the overlapping 1MLCT band, thus providing a lower contribution to the absorption in this region. The 1MLCT absorption maximum of the photoproduct is consistent with that of the reported spectrum for [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(OH2)]2+,19b indicative of the exchange of Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN for a solvent water molecule upon irradiation. These results parallel those obtained for 3 shown in Figure S4b. The quantum yields of photoinduced ligand exchange in water were measured to be 0.00014(3) and 0.00023(1) for 1 and 3, respectively (λirr = 450 nm). The observation that the quantum yields for the two dppn complexes are lower than those measured for the corresponding bpy compounds can be explained by the competitive population of the long-lived dppn 3ππ* state in the former, reducing that of the dissociative 3LF state. It should be noted that each complex is stable in solution in the dark for at least 30 minutes (Figures S5-S8), which represents an important feature in the design of light activated chemotherapeutic agents.

The incorporation of the dppn ligand in 1 renders the complex in its excited state capable of 1O2 generation, and a quantum yield ΦΔ, of 0.64(3) was measured for the process in air-saturated methanol (λirr = 460 nm). As expected, a similar ΦΔ value was measured for 3, 0.67(6), under similar experimental conditions. It should also be noted that the photoproduct of ligand exchange for complexes 1 and 3, [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(OH2)]2+, is capable of 1O2 generation with a quantum yield, ΦΔ, of 0.52(1). These values are in agreement with that reported for the related complex [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)(py)]2+, ΦΔ = 0.69(9).33a It is believed that the ΦΔ values for these complexes are lower than unity because of the competitive population of the dppn/Me2dppn-centered 3ππ* state and the dissociative 3LF state from the 3MLCT state. In contrast, [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(py)]2+, which does not undergo ligand exchange upon excitation, produces 1O2 with ΦΔ = 0.98(6),33a explained by the absence of competitive population of the 3LF and 3ππ* states in this complex. The production of 1O2 is not observed for 2 or 4, since these complexes do not possess long-lived excited states able to transfer energy to 3O2 in solution.

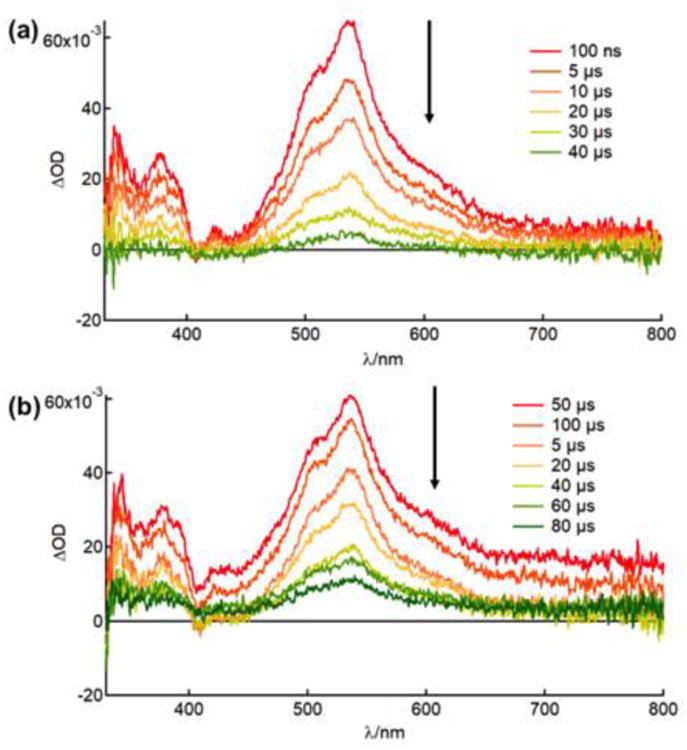

The long lived excited state of 1, 3, and 5 were investigated by nanosecond transient absorption spectroscopy (nsTA). Figure 3 shows the nsTA spectra of 1 and 3 in deaerated acetonitrile and both feature a strong positive signal centered at ∼540 nm that decays monoexponentially with lifetimes of 22 μs and 20 μs respectively (λexc = 480 nm, 5 mJ/pluse). The features of the excited state absorption and their lifetimes are consistent with the reported nsTA spectra of complexes containing dppn ligands, such as [Ru(bpy)2(dppn)]2+ (τ = 33 μs) and [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(py)]2+ (τ = 50 μs), and assigned to the dppn-centered 3ππ* state.15,33a The nsTA spectrum of 5 could not be obtained in acetonitrile due its rapid conversion to the acetonitrile bound complex 3. The nsTA experiments were also performed in deaerated methanol (<5% acetone), where 1, 3, and 5 exhibit a strong positive feature centered at ∼540 nm that decays monoexponentially with lifetimes of 34 μs, 36 μs, and 3.1 μs respectively (λexc = 480 nm, 5 mJ/pluse). Once exposed to air, the lifetime of each complex decreases dramatically to 260 ns, 397 ns and 338 ns for 1, 3, and 5, respectively, in methanol due to the quenching of the excited state by dissolved oxygen, resulting in respective calculated Stern-Volmer quenching rate constants, kq, of 3.7 × 108 M−1s−1, 2.4 × 108 M−1s−1, and 2.6 × 108 M−1s−1. These values are on the same order of magnitude as other bimolecular quenching constants by oxygen, for example, 2.8 × 108 M−1s−1 for [Ir(phen)3]3+ (phen = 1,10-phenanthroline) and 3.4 × 108 M−1s−1 for [Ir(bpy)3]3+ in methanol.40,41

Figure 3.

Transient absorption spectra of (a) 1 and (b) 3 in CH3CN under N2 atmosphere (λexc = 480 nm, irf = 5.5 ns, 5 mJ/pluse).

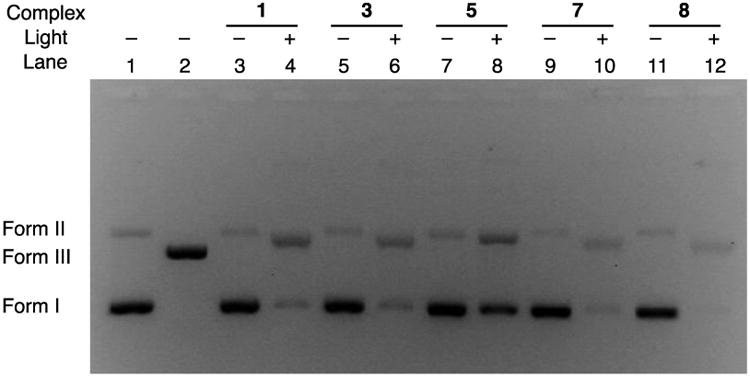

DNA Photocleavage

The ability of the complexes containing the dppn ligand, 1 and 3, and the dppn-containing photoproduct 5 were evaluated for their ability to photocleave DNA upon irradiation in air (λirr ≥ 395 nm). Lane 1 of Figure 4 shows supercoiled pUC19 plasmid (form I, 100 μM bases) in the absence of any complex, featuring a small amount of the nicked open circular impurities (form II), while lane 2 shows the position of the band corresponding to pUC19 plasmid linearized by the SmaI restriction enzyme (form III). In the absence of light, 10 μM of the dppn-containing complexes 1, 3, and 5 do not result in the cleavage of DNA, as evidenced by lanes 3, 5, and 7, respectively. However, irradiation of each complex in air (λirr ≥ 395 nm), lanes 4, 6, and 8, respectively, results in an increase of the amount of nicked open circular DNA (form II). This DNA photocleavage is similar to that previously reported by us and can be attributed to the production of 1O2, a species known to result in the generation of 8-oxo-guanine, a base modification that leads to DNA damage.43,44 These results are consistent to those previously reported for related complexes of dppn, [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(py)]2+ (7), reproduced in lanes 9 (dark) and 10 (irradiated) and [Ru(bpy)2(dppn)]2+ (8), reproduced in lanes 11 (dark) and 12 (irradiated), both of which are only able to produce singlet oxygen upon irradiation and do not undergo ligand exchange.15,33a The photoproduct of 1 and 3, [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(OH2)]2+ (5), is also able to cleave DNA upon irradiation, as compared in lanes 7 (dark) and 8 (irradiated). This finding suggests that after the inhibitor is delivered, the remaining ruthenium fragment is still able to produce singlet oxygen but not as efficiently as the parent complexes 1 and 3. The bpy complexes 2, 4 and [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(OH2)]2+ did not display DNA photocleavage under similar experimental conditions (Figure S9), consistent with their lack of ability to sensitize the production of 1O2.

Figure 4.

Ethidium bromide-imaged agarose gel (1%) of 100 μM pUC19 and 10 μM of each complex in air (5 μM Tris buffer, pH = 7.5, 50 μM NaCl); lanes 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11 were kept in the dark and lanes 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 were irradiated (λirr ≥ 395 nm, 5 min); lane 1, plasmid only; lane 2 plasmid treated with SmaI; lanes 3 and 4, 1; lanes 5 and 6, 3; lanes 7 and 8, 5; lanes 9 and 10, 7; and lanes 11 and 12, 8.

Conclusions

[Ru(tpy)(dppn)(Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN)]2+, 1, represents a potential PDT agent with dual reactivity, undergoing ligand exchange to deliver a known cysteine protease inhibitor Cbz-Leu-NHCH2CN, and producing 1O2 upon irradiation with visible light. The presence of the dppn ligand in the complex results in a long-lived ligand-centered 3ππ* state able to produce 1O2 in good yield upon irradiation with visible light. Although the quantum yield for ligand exchange decreases with the introduction of the dppn ligand, the ability of 1 to undergo both processes with spatiotemporal control is promising to achieve anticancer activity via two different mechanisms. In addition, the resulting ligand exchange photoproduct of 1, [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(OH2)]2+ (5), is also able to produce 1O2 in good yield, such that the latter may continue to result in cell death after the inhibitor is delivered. As such, the dual activity of 1 upon exposure to visible light makes it an attractive candidate for further photochemotherapeutic investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Institutes of Health (EB 016072) for their generous support.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest. There are no conflicts to declare

References

- 1.Dolmans DEJGJ, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:380–387. doi: 10.1038/nrc1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Civantos FJ, Karakullukcu B, Biel M, Silver CE, Rinaldo A, Saba NF, Takes RP, Vander Poorten V, Ferlito A. Adv Ther. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0659-3. Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Heinemann F, Karges J, Gasser G. Acc Chem Res. 2017;50:2727–2736. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mari C, Pierroz V, Ferrari S, Gasser G. Chem Sci. 2015;6:2660–2686. doi: 10.1039/c4sc03759f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lange C, Bednarski PJ. Curr Pharm Des. 2017;22:6956–6974. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666161124155344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abrahamse H, Hamblin MR. Biochem J. 2016;473:347–364. doi: 10.1042/BJ20150942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dichiara M, Prezzavento O, Marrazzo A, Pittala V, Salerno L, Rescifina A, Amata E. Eur J Med Chem. 2017;142:459–485. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonnet S. Comments Inorg Chem. 2015;35:179–213. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li X, Zheng BD, Peng XH, Li SZ, Ying JW, Zhao Y, Huang JD, Yoon J. Coord Chem Rev. 2017 Ahead of Print. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanielian C, Schweitzer C, Mechin R, Wolff C. Free Rad Biol Med. 2001;30:208–212. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dellinger M. Photochem Photobiol. 1996;64:182–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1996.tb02440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joyce LE, Aguirre JD, Angeles-Boza AM, Chouai A, Fu PKL, Dunbar KR, Turro C. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:5371–5376. doi: 10.1021/ic100588d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juris A, Balzani V, Barigelletti F, Campagna S, Belser P, von Zelewsky A. Coord Chem Rev. 1988;84:85–277. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCusker JK. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:876–887. doi: 10.1021/ar030111d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhattacharyya K, Das P. Chem Phys Lett. 1985;116:326–332. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun Y, Joyce LE, Dickson NM, Turro C. Chem Commun. 2010;46:2426–2428. doi: 10.1039/b925574e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stephenson M, Reichardt C, Pinto M, Wächtler M, Sainuddin T, Shi G, Yin H, Monro S, Sampson E, Dietzek B, Mcfarland SA. J Phys Chem A. 2014;118:10507–10521. doi: 10.1021/jp504330s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li X, Lee S, Yoon J. Chem Soc Rev. 2018;47:1174–1188. doi: 10.1039/c7cs00594f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Zamora A, Denning CA, Heidary DK, Wachter E, Nease LA, Ruiza J, Glazer EC. Dalton Trans. 2017;46:2165–2173. doi: 10.1039/c6dt04405k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kohler L, Nease L, Vo P, Garofolo J, Heidary DK, Thummel RP, Glazer EC. Inorg Chem. 2017;56:12214–12223. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b01642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Howerton BS, Heidary DK, Glazer EC. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8324–8327. doi: 10.1021/ja3009677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Siewert B, van Rixel VHS, van Rooden EJ, Hopkins SL, Moester MJB, Ariese F, Siegler MA, Bonnet S. Chem Eur J. 2016;22:10960–10968. doi: 10.1002/chem.201600927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lameijer LN, Hopkins SL, Brevé TG, Askes SHC, Bonnet S. Chem Eur J. 2016;22:18484–18491. doi: 10.1002/chem.201603066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Li A, Turro C, Kodanko JJ. Chem Commun. 2018;54:1280–1290. doi: 10.1039/c7cc09000e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li A, Yadav R, White, Herroon JKMK, Callahan BP, Podgorski I, Turro C, Kodanko JJ. Chem Commun. 2017;53:3673–3676. doi: 10.1039/c7cc01459g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Herroon MK, Sharma R, Rajagurubandara E, Turro C, Kodanko JJ, Podgorski I. Biol Chem. 2016;397:571–582. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2015-0274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Respondek T, Garner RN, Herroon MK, Podgorski I, Turro C, Kodanko JJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:17164–17167. doi: 10.1021/ja208084s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Brabec V, Pracharova J, Stepanokova J, Sadler PJ, Kasparkova J. J Inorg Biochem. 2016;160:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2015.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Smith NA, Zhang P, Geenough SE, Horbury MD, Clarkson GJ, McFeely D, Habtemariam A, Salassa L, Stavros VG, Dowson CG, Sadler PJ. Chem Sci. 2017;8:395–404. doi: 10.1039/c6sc03028a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Ford PC. Nitric Oxide. 2013;34:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ostrowski AD, Ford PC. Dalton Trans. 2009:10660–10669. doi: 10.1039/b912898k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bjelosevic A, Pages BJ, Spare LK, Deo KM, Ang DL, Aldrich-Wright JR. Curr Med Chem. 2018;25:478–492. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666170530085123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reeβing F, Szymanski W. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24:4905–4950. doi: 10.2174/0929867323666160906103223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Wagenknecht PS, Ford PC. Coord Chem Rev. 2011;255:591–616. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ford PC. Coord Chem Rev. 1982;44:61–82. [Google Scholar]; (c) Malouf G, Ford PC. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:7213–7221. [Google Scholar]; (d) Malouf G, Ford PC. J Am Chem Soc. 1974;96:601–603. [Google Scholar]

- 26.White JK, Schmehl RH, Turro C. Inorg Chim Acta. 2017;454:7–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durham B, Caspar JV, Nagle JK, Meyer TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:4803–4810. [Google Scholar]

- 28.(a) Garner RN, Gallucci JC, Dunbar KR, Turro C. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:9213–9215. doi: 10.1021/ic201615u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Singh TN, Turro C. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:7260–7262. doi: 10.1021/ic049075k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sgambellone MA, David A, Garner RN, Dunbar KR, Turro C. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:11274–11282. doi: 10.1021/ja4045604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Respondek T, Sharma R, Herroon MK, Garner RN, Knoll JD, Cueny E, Turro C, Podgorski I, Kodanko JJ. ChemMedChem. 2014;9:1306–1315. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201400081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mosquera J, Sánchez MI, Mascareñas JL, Vázquez ME. Chem Commun. 2015;51:5501–5504. doi: 10.1039/c4cc08049a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albani BA, Peña B, Leed NA, de Paula NABG, Pavani C, Baptista MS, Dunbar KR, Turro C. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:17095–17101. doi: 10.1021/ja508272h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Knoll JD, Albani BA, Turro C. Chem Commun. 2015;51:8777–8780. doi: 10.1039/c5cc01865j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Loftus LM, White JK, Albani BA, Kohler L, Kodanko JJ, Thummel RP, Dunbar KR, Turro C. Chem Eur J. 2016;22:3704–3708. doi: 10.1002/chem.201504800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Knoll JD, Albani BA, Turro C. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:2280–2287. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Platt MO, Dumas JE. Tumor Angiogenesis Regulators. 2013:297–339. [Google Scholar]

- 35.(a) Sullivan BP, Calvert JM, Meyer TJ. Inorg Chem. 1980;19:1404–1407. [Google Scholar]; (b) Takeuchi KJ, Thompson MS, Pipes DW, Meyer TJ. Inorg Chem. 1984;23:1845–1851. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hecker CR, Fanwick PE, McMillin DR. Inorg Chem. 1991;30:659–666. [Google Scholar]

- 37.McConnell AJ, Lim MH, Olmon ED, Song H, Dervan EE, Barton JK. Inorg Chem. 2012;51:12511–12520. doi: 10.1021/ic3019524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foxon SP, Green C, Walker MG, Wragg A, Adams H, Weinstein JA, Parker SC, Meijer AJHM, Thomas JA. Inorg Chem. 2012;51:463–471. doi: 10.1021/ic201914h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Löser R, Schilling K, Dimmig E, Gütschow M. J Med Chem. 2005;48:7688–7707. doi: 10.1021/jm050686b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montalti M, Credi A, Prodi L, Gandolfi MT. Handbook of Photochemistry. 3rd. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Demas JN, Harris EW, McBride RP. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:3547–3551. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lampe FW, Noyes RM. J Am Chem Soc. 1954;76:2140–2144. [Google Scholar]

- 43.(a) Liu Y, Hammitt R, Lutterman DA, Joyce LE, Thummel RP, Turro C. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:375–385. doi: 10.1021/ic801636u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhao R, Hammitt R, Thummel RP, Liu Y, Turro C, Snapka RM. Dalton Trans. 2009:10926–10931. doi: 10.1039/b913959a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cadet J, Douki T, Gasparutto D, Ravanat JL. Mutat Res - Fundam Mol Mech Mutagen. 2003;531:5–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.