Abstract

Objective:

Low-dose hydrocortisone (LDH) enhances aspects of learning and memory in select populations including patients with PTSD and HIV-infected men. HIV-infected women show impairments in learning and memory, but the cognitive effects of LDH in HIV-infected women are unknown.

Design:

Double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study examining the time-dependent effects of a single low-dose administration of hydrocortisone (10mg oral) on cognition in 36 HIV-infected women. Participants were first randomized to LDH or placebo and then received the opposite treatment one month later.

Methods:

Cognitive performance was assessed 30 minutes and 4 hours after pill administration to assess, respectively nongenomic and genomic effects. Self-reported stress/anxiety and salivary cortisol were assessed throughout sessions.

Results:

LDH significantly increased salivary cortisol levels versus placebo; levels returned to baseline 4-hours post-administration. At the 30-minute assessment, LDH enhanced verbal learning and delayed memory, working memory, behavioral inhibition, and visuospatial abilities. At the 4-hour assessment, LDH enhanced verbal learning and delayed memory compared to placebo. LDH-induced cognitive benefits related to reductions in cytokines and to a lesser extent to increases in cortisol.

Conclusions:

The extended benefits from 30 minutes to 4 hours of a single administration of LDH on learning and delayed memory suggest that targeting the HPA axis may have potential clinical utility in HIV-infected women. These findings contrast with our findings in HIV-infected men who showed improved learning only at the 30-minute assessment. Larger, longer-term studies are underway to verify possible cognitive enhancing effects of LDH and the clinical significance of these effects in HIV.

Keywords: hydrocortisone, immune, cognition, HIV, women

Introduction

Despite effective antiretroviral therapies, milder forms of cognitive impairment persist among people living with HIV (PLWH). To date, very little is known about the pathophysiology underlying HIV-associated complications among PLWH on antiretrovirals. Potential mechanisms of HIV-associated cognitive impairment include direct neurotoxic effects of the virus such as the release of neurotoxic viral proteins such as Tat and gp120[1], as well as indirect neurotoxic monocyte-driven inflammatory processes[2]. Characterizing the mechanisms underlying cognitive impairment will facilitate the development of new cognitive therapies among PLWH.

A new target for the development of cognitive therapeutics for HIV is the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, a key mediator of the stress response. With inhibitory feedback regulation from prefrontal and limbic (e.g., hippocampal) regions, the HPA axis mediates the systemic release of glucocorticoids (GCs). These effects are mediated by the binding of cortisol to GC receptors in prefrontal and hippocampal brain regions[3–7]. Alterations in HPA axis function, including excessive release of cortisol and changes in GC receptor can influence cognitive abilities subserved by these brain regions[8]. The HPA axis can also influence cognition through immunomodulatory effects, including the regulation of cytokine production. In homeostasis, the HPA axis activates innate immunity and promotes the development of an adaptive, protective immune responses such as the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines and the inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines[9, 10]. Conversely, perturbations in the HPA axis can impair cognition through cytokine-driven neuroinflammation. The communication between the HPA axis and immune system is bidirectional so that not only do increases in GCs promote proinflammatory cytokines but also proinflammatory cytokines stimulate GC release[9, 10].

Viral infections such as HIV induce high levels of circulating inflammatory cytokines which can activate the HPA axis at several levels. HIV-infected men show alterations in HPA axis function, including elevated basal cortisol levels, increased cortisol over time, attenuated cortisol responsivity to behavioral and corticotropin-releasing hormone challenges, and alterations in the diurnal rhythm of cortisol secretion[11–18]. However, studies have not examined alterations in cortisol relation to cognition. Similarly, although in healthy individuals immune parameters such as interleukin(IL)-6, IL-β, and C-reactive protein (CRP) shift following psychosocial stress paradigms that engage the HPA axis[19], studies have not examined these effects in PLWH nor have they linked such effects to cognition. It is known that peripheral systemic inflammatory markers including IL-6, IL-β, interferon metabolism (IP-10), CRP, and soluble levels of monocyte cell surface markers (sCD163, sCD14) are associated with cognitive dysfunction among PLWH[20–23]. It remains to be determined whether altering the HPA axis in HIV can influence cognition through effects on cytokine production.

One experimental approach used to investigate the influence of the HPA axis on learning and memory impairment in HIV is a pharmacological challenge study involving the administration of a low-dose hydrocortisone, an exogenous GC. The GC challenge probes HPA-axis related cortisol and immune changes which may be involved in HIV-related cognitive alterations and offers strengths as an experimental approach to studying the role of the HPA axis, immune function, and cognition. This approach focuses on the causal role of GCs as a specific mechanism that induces cognitive change. Whereas psychosocial stress paradigms not only produce elevations in cortisol in most participants but also increases subjective stress[24], the GC challenge does not typically induce elevations in subjective stress and allows control over the dose of cortisol. With LDH, the time-dependent effects of cortisol-induced cognitive changes can be examined in order to distinguish rapid, nongenomic mechanisms that are evident shortly after LDH administration (e.g., 30 minutes) from slower genomic mechanisms (e.g., 4 hours post-pill administration)[25, 26]. The delayed time points are of particular interest as they inform understanding of the possible benefits of daily LDH administration since long-term LDH use would affect cognition primarily through genomic mechanisms.

Studies of healthy individuals, HIV-infected men, and individuals with mental health issues such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression demonstrate that LDH administration reliably increases salivary cortisol levels[25, 27–29]. Whether LDH induces positive or negative cognitive effects depends on a number of factors including mental health status, sex, dose, and timing between LDH administration and cognitive testing[30–34]. For example, LDH can impair aspects of declarative memory (e.g., delayed free recall of words, word-pairs, or pictures) in healthy individuals[31, 35] and has no effect on autobiographical verbal memory or verbal working memory in acute depression[36, 37]. However, LDH enhances episodic verbal learning, episodic verbal memory (paragraph free recall), declarative verbal memory, autobiographical verbal memory, and verbal working memory (Letter-Number Sequencing, Digit Span Backwards) in PTSD[38–41]. We also found LDH to enhance verbal learning (single trial learning; total learning across trials) and delayed recall on the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-R (HVLT-R) in HIV-infected men 30 minutes after LDH administration[29]. While the mechanisms underlying these varied effects of LDH on these cognitive abilities are unknown, they may depend in part on basal cortisol levels, levels of neuroinflammation, and/or GC receptor availability, sensitivity, and/or function. Such effects may also depend on sex as there are sex differences in HPA axis activity and HPA-related cognitive effects[42, 43].

Here we investigated the time-dependent effects of LDH on verbal learning and delayed memory in HIV-infected women an understudied group. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over design, 36 HIV-infected women received 10mg of hydrocortisone (LDH) or placebo before cognitive testing which occurred 30-minutes and 4-hours post-pill administration. Given our findings in HIV-infected men, we hypothesized that LDH relative to placebo would enhance verbal learning and delayed memory 30-minutes post LDH administration. We also hypothesized that LDH administration may change these abilities by inducing changes in immune functioning[44, 45].

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from HIV primary care clinics in the Chicago-land area via advertisements and websites. Inclusionary criteria included confirmed HIV seropositivity via medical record, age 18 to 45 years, English as first language, and use of same antiretrovirals for at least three months. Exclusionary criteria included history of psychosis or Axis I mood or anxiety disorder in the past month based on a structured clinical interview, reported neurological conditions affecting cognition, body mass index greater than 40, history of substance abuse/dependence in the past 6 months, and evidence of illicit substance use 24 hours before testing on urine toxicology screen. Participants received compensation for travel and time.

Procedures

Participants were first screened by phone for interest and general inclusion/exclusion criteria. Qualifying interested participants visited the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) for an initial visit (Session 1) where they provided informed consent and completed a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (SCID) IV interview, toxicology screen, vitals assessment, and questionnaires, including: Childhood Trauma Questionnaire[46], Schedule of Life Events checklist[47], PTSD Checklist–Civilian version[48], Perceived Stress Scale[49], Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)[50], Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index[51], and Medication Adherence Self-Report Inventory[52].

The study design was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over pharmacologic challenge study. The within-subject design controls for individual difference factors including education and premorbid intelligence. After screening (Session 1), participants returned for two subsequent visits (Sessions 2 and 3) that comprised the LDH and placebo testing sessions. Participants were randomized by UIC’s Investigational Drug Service (IDS) to receive either LDH (10 mg orally; Qualitest®) or placebo at Session 2 and then received the opposite treatment at Session 3. To maintain blinding, UIC IDS encapsulated LDH tablets and placebo tablets which were made from microcrystalline cellulose. Parallel procedures were used at Sessions 2 and 3 and entailed a toxicology screen, pregnancy test, blood draw, vitals assessment, completion of questionnaires and cognitive assessments, and collection of saliva samples. Cognitive assessments occurred 30 minutes and 4 hours post-pill administration. Session 2 occurred within one week of Session 1, and Session 3 occurred approximately one month after Session 2. To control for diurnal variations in cortisol[53–55], Sessions 2 and 3 occurred between 12:00 pm (±30min) and 6:00 pm (±30min).

Cognitive Measures and Outcomes

Verbal learning and memory was assessed with the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT-R; learning=immediate Trial 1 learning and total learning across Trials 1–3; memory=delayed recall; strategic organizational encoding and retrieval strategies =semantic clustering across Trials 1–3 and during delayed recall)[56]. Attention and concentration was assessed with the control condition of the Letter-Number Sequencing (LNS) task from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale IV (total correct)[57], Trail Making Test (TMT) Part A (time to completion)[58], and congruent trials on the computerized Stroop Test (accuracy)[59]. Executive functioning was assessed with the experimental condition of LNS (working memory; total correct)[57], TMT Part B (mental flexibility, time to completion)[58], and incongruent trials on Stroop (behavioral inhibition, accuracy). Visuospatial ability was assessed with the Line Orientation Task from the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS; total correct)[60].

The cognitive test battery administered 30 minutes post-pill administration at Sessions 2 and 3 included HVLT, LNS, TMT Parts A and B, Stroop, and Line Orientation (administration time = 35–45 minutes). The cognitive battery administered 4 hours post-pill administration at Sessions 2 and 3 included HVLT, LNS, and TMT (administration time=35–45 minutes). Four alternate versions of the HVLT, LNS and TMT tests were used to minimize carryover effects[61–63]. Forms were administered in a counterbalanced manner. Stroop was only administered 30 minutes post-pill administration because this task is more susceptible to practice effects than the other tests administered[63].

Saliva collection and analysis of cortisol and cytokine levels

To minimize the influence of external factors on cortisol levels, participants were instructed to refrain from recreational drugs and alcohol for 24 hours before study sessions, refrain from caffeine/physical exertion for three hours before appointments, eat a light breakfast low in fat/protein, and refrain from smoking the day of appointments. During Sessions 2 and 3, salivary samples were obtained at 10 time points. Baseline measures were taken 35 and 20 minutes before pill administration. Saliva was then measured 30, 60, 90, 180, 210, 240, 270, and 300 minutes after pill administration. Saliva was collected via straws into Nalgene tubes, stored at −80 degrees, batch shipped to Salimetrics, and assayed for cortisol with an enzymeimmunoassay kit (sensitivity <0.007μg/dL).

For salivary cytokines, saliva was collected at three time points, once 20 minutes before pill administration (baseline) and then 30 and 240 minutes after pill administration. Fourteen cytokines were assessed, including IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor-(TNF)-α, CRP, macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), IP-10, monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1, monokine induced by interferon (MIG), cell surface receptor TNF receptor type 2 (TNFRII), and matrix metalloproteinase MMP-9, MMP-2, sCD163, and sCD14. Saliva was assayed using a MILLIPLEX MAP human high sensitivity T cell panel immunology multiplex assay (Millipore, Billerica, MA) to detect IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α (standard curves 0.18–7500pg/mL; average interplate coefficient of variation [CV]=9.9%); MILLIPLEX MAP standard sensitivity cytokine to detect IP-10 and MCP-1 (standard curve 3.2–10,000 pg/mL; average interplate CV=9%); R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN) singleplex to detect soluble TNFRII (12–50,000pg/mL; average interplate CV=5.75%), and R&D systems custom 5-plex to detect CRP, MIP, MIG, MMP-2, and MMP-9 (144–96,000pg/mL; average interplate CV=12.7%). Testing was performed following manufacturer’s procedures. Standards and experimental samples were tested in duplicate. Milliplex results were acquired on a Labscan 200 analyzer (Luminex, Austin, Tx) using Bio-Plex manager software 6.1 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). R&D Systems ELISAs were used to measure sCD14 and sCD163, plates were read and analyzed by SoftmaxPro (250–16000pg/mL; interplate; average interplate CV<6%, and 1.5–100pg/mL; average interplate CV<6%, respectively). A 5-point logistic regression curve was used to calculate the concentration from the fluorescence intensity of the bead measurements. Samples below the level of detection were assigned one-half the lowest detectable value for that analyte. All cytokine values were log transformed due to nonnormal distributions.

IL-8, IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, IP-10, MCP1, CRP, MIG, and MMP9 were included in the original panel of markers. Any missing values would reflect insufficient sample. sCD163, sCD14, TNFRII, MIF, and MMP2 were added for assessment as the study progressed given there relevance to HIV and/or cognitive functioning/impairment[22, 23, 64–69]. Thus, these markers are not available on all participants.

Psychological Measures

Self-reported measures of stress and anxiety were obtained at 10 time points concurrent with saliva sampling. Measures included State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: Short Form (STAI)[70] and a two-item Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) measuring how “anxious” and “stressed” participants felt on a 10-cm line.

Statistical Analysis

A series of mixed-effects regression models (MRM, random intercept) were conducted to examine the effects of LDH versus placebo on salivary cortisol levels, psychological measures, and cognition. Models included the following predictors: Treatment (LDH, placebo), Time (Acute, Delayed), and Treatment x Time interaction. Of primary interest was the effect of Treatment when Time=0 (Acute) and when Time=1 (Delayed). Modeling acute and delayed effects in one model enabled adjustment for within-subject trends across time. To account for potential bias due to carry-over effects, models adjusted for sequence of cognitive testing forms and treatment sequence (Supplemental Table 1 provides MRM results examining practice effects). Additional MRMs were conducted to determine LDH-induced cytokine changes and correlations were conducted to determine whether those changes were related to LHD-related cognitive changes. For cytokines, we first computed the median cytokine value across three saliva samples from the placebo day[71]. By using the median of the three placebo day values, we accounted for normal variation in cytokine levels. Then we computed the change from the median cytokine value from the placebo day to acute (e.g., (median on placebo day – LDH acute)) and delayed time points during the LDH session.

Based on the cognition analyses, exploratory Pearson correlations were conducted to determine potential mechanisms of LHD-related cognitive changes. Correlations were conducted between LDH-related cortisol (area under the curve-[AUC]-with respect to ground[72]) and immune responsivity (median on placebo day – LDH) and LDH-related cognitive changes (LDH - placebo). Given that these exploratory correlational analyses were performed for heuristic purposes to examine the potential mechanistic role of cortisol and inflammation, we did not correct for multiple comparisons. Analyses were conducted in SAS (v.9.4 for Windows; SAS); significance was set at p<0.05. Cohen’s d effect sizes were computed (small=0.3; medium=0.5)[73].

Results

Among the 36 HIV-infected women, current HIV plasma viral load was undetectable for 42%, and 28% had values at the lowest detectable limit (20 cp/ml)(Table 1). The prevalence of elevated depressive symptoms (42% CES-D score ≥16) and reported history of sexual abuse (36%) was high. Women reported on average 7.5 stressful life events in the past 6 months and above-average levels of perceived stress in the past month[74].

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics for HIV-infected women at enrollment visit, Session 1 (n=36).

| Variables | M (SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Socio-demographic factors | |

| Age | 36.63 (7.40) |

| Education | |

| <High school | 14 (39) |

| High school graduate | 13 (36) |

| >High school | 9 (25) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Black, not Hispanic | 34 (94) |

| White, not Hispanic | 1 (3) |

| Other | 1 (3) |

| Unemployed | 20 (56) |

| Smoking | |

| Never | 14 (39) |

| Former | 6 (17) |

| Current | 16 (44) |

| Number of Alcohol drinks/week | 0.47 (0.73) |

| Current use | |

| Marijuana | 8 (22) |

| Number of times used/week | 4.28 (2.93) |

| Positive marijuana toxicology screen | 9 (25) |

| Cocaine | 2 (5) |

| Heroin | – |

| Methadone | 1 (3) |

| Methamphetamines | – |

| Ever dependent/abuse alcohol | 2 (5) |

| Ever dependent/abuse substances | 13 (36) |

| Psychological profile | |

| Lifetime Major depression† but not past year | 18 (50) |

| Depressive symptoms (CES-D)(range: 0–60) | 15.86 (9.04) |

| Perceived stress (PSS-10)(range: 0–40) | 22.2 (5.78) |

| PTSD symptoms (PCL-C)(range: 17–85) | 35.53 (14.67) |

| Childhood Trauma (CTQ) | |

| Emotional abuse (range: 5–25) | 11.55 (6.00) |

| Physical abuse (range: 5–25) | 10.63 (6.30) |

| Sexual abuse (range: 5–25) | 9.19 (6.74) |

| Emotional neglect (range: 5–25) | 12.53 (4.66) |

| Physical neglect (range: 5–25) | 9.58 (4.39) |

| Negative Life events (SLE)(range: 0–54) | 7.52 (4.77) |

| Exposure to interpersonal violenceⱡ | 12 (33) |

| Exposure to sexual abuseⱡ | 13 (36) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Body mass index | 28.52 (5.29) |

| Years living with HIV | 12.19 (6.05) |

| Medication adherence (MASRI) missing ≥1 dose: | |

| 3 days summated before visit | 11 (30) |

| 2 weeks before visit | 13 (36) |

| Last month± | 16 (44) |

| CD4 Count (cells/μl) | |

| > 500 | 18 (50) |

| ≥ 200 and ≤ 500 | 14 (39) |

| < 200 | 4 (11) |

| Viral Load (HIV RNA (cp/ml)) | |

| Undetectable | 15 (42) |

| Lowest detectable limit (20 cp/ml) | 10 (28) |

| < 10,000 | 7 (19) |

| ≥ 10,000 | 4 (11) |

Note. IQR=Interquartile Range. Current use=use in the last month. CES-D= Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; PSS-10=Perceived Stress Scale; PCL-C=PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version; CTQ=Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; SLE=Schedule of Negative Life Events Checklist; PSQI=Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; MASRI= Medication Adherence Self-Report Inventory† based on the Structural Clinical Interview of Mental Health Disorders (SCID); ±visual analogue scale for proportion of doses taken in the last month; ⱡbased on information extracted from the PTSD module on the SCID.

Effects of LDH versus Placebo in HIV-infected women

At 30 and 45 minutes before LDH and placebo (i.e., baseline) mean salivary cortisol levels were 0.21ug/dl (5.8nmol/L) and 0.19ug/dl (5.2nmol/L). Cortisol levels changed across study duration following LDH administration but not placebo. Compared to baseline levels, cortisol levels increased at 105 and 150 minutes post-LDH administration (p’s<0.001), the time frame when the first “acute” cognitive battery was administered. Importantly, cortisol levels returned to baseline levels at the 315 and 360 minute time points following LDH (p’s>0.11), the time frame when the second “delayed” cognitive assessment was obtained. Cortisol levels remained stable across the placebo study session. Following LDH and placebo, self-reported anxiety on the STAI (Treatment x Time p=0.10) and VAS remained stable across study duration and Session (Treatment x Time p’s>0.18).

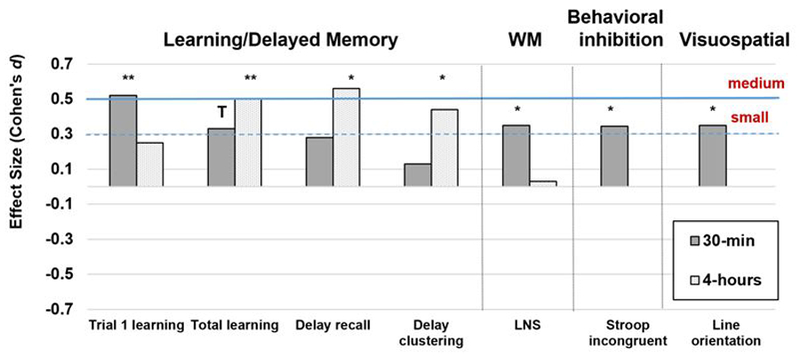

At the 30-minute time point, LDH improved performance versus placebo on HVLT trial 1 learning and delayed recall, LNS working memory, Stroop incongruent trials, and line orientation (Table 2; Figure 1). The effects of LDH versus placebo were substantially larger than any benefit due to practice on all outcomes except LNS working memory (Supplemental Table 1). Specifically, the LDH effects versus placebo were >200% greater than the benefit gained from practice on HVLT trial 1 ((0.22 from practice – 0.78 from LDH)/0.22), 59% greater on delayed recall, 17% greater on Stroop incongruent trials, and >300% greater on line orientation. Although LDH benefits were seen on LNS working memory, the benefit was 17% less than the benefit derived from practice. At the 4-hour time point, LDH improved performance versus placebo on HVLT total learning, delayed recall, and strategic organizational retrieval strategies. The effects of LDH versus placebo were >500% larger than any benefit due to practice on all of these HVLT outcome measures. Controlling for strategic organizational retrieval strategies eliminated the delayed effect of LDH on delayed recall (p=0.29).

Table 2.

Time-dependent effects of low-dose hydrocortisone (LDH) versus placebo on cognition in HIV-infected women.

| Time point tested post-pill |

Time Effects of LDH vs Placebo | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate, rapid (30 min) | Delayed, slow (4 hours) | ||||||

| Outcome measures | Placebo M (SE) | LDH M (SE) | LDH vs Placebo B (SE) | Placebo M (SE) | LDH M (SE) | LDH vs Placebo B (SE) | F |

| Learning/Memory | |||||||

| HVLT | |||||||

| Immediate Trial 1 Learning | 5.33 (0.30) | 6.11 (0.26) | 0.78 (0.29)** | 5.05 (0.30) | 5.47 (0.30) | 0.42 (0.29) | 8.42** |

| Total learning | 20.57 (0.86) | 21.77 (0.85) | 1.19 (0.64)T | 19.18 (0.85) | 20.99 (0.86) | 1.81 (0.64)** | 10.98*** |

| Delay recall | 5.90 (0.49) | 6.52 (0.49) | 0.61 (0.39) | 4.49 (0.49) | 5.48 (0.49) | 1.00 (0.40)* | 8.27** |

| Strategic organizational strategies | |||||||

| Semantic clustering Trials 1–3 | 6.52 (0.80) | 6.69 (0.80) | 0.17 (0.80) | 5.88 (0.80) | 6.89 (0.80) | 1.00 (0.63) | 1.70 |

| Semantic clustering Delay recall | 2.16 (0.37) | 2.38 (0.37) | 0.22 (0.29) | 1.72 (0.36) | 2.38 (0.37) | 0.67 (0.29)* | 4.75* |

| Executive Function | |||||||

| LNS working memory condition | 9.99 (0.54) | 11.21 (0.54) | 1.22 (0.51)* | 11.35 (0.54) | 11.46 (0.54) | 0.11 (0.51) | 3.37T |

| TMT Part B∥ | 4.74 (0.08) | 4.66 (0.08) | -0.08 (0.07) | 4.58 (0.08) | 4.63 (0.08) | 0.05 (0.08) | 0.79 |

| Stroop Incongruent Trials | 0.82 (0.03) | 0.89 (0.03) | 0.06 (0.03)* | – | – | – | 4.52* |

| Attention/Concentration | |||||||

| LNS attention condition | 13.10 (0.55) | 12.62 (0.56) | -0.48 (0.47) | 13.48 (0.56) | 13.38 (0.56) | -0.10 (0.47) | 0.77 |

| TMT Part A∥ | 3.66 (0.06) | 3.71 (0.06) | 0.05 (0.05) | 3.61 (0.06) | 3.57 (0.06) | -0.04 (0.05) | 0.00 |

| Stroop Congruent Trials | 0.96 (0.01) | 0.98 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | – | – | – | 1.64 |

| Visuospatial abilities | |||||||

| Line Orientation Test | 11.82 (0.71) | 13.21 (0.71) | 1.39 (0.64)* | – | – | – | 4.68* |

Note.

p<0.001;

p<0.01;

p<0.05.

=0.06.

Log transformed values.

LDH=low-dose hydrocortisone; HVLT=Hopkins Verbal Learning Test; LNS= Letter-Number Sequencing (LNS) task; TMT=Trail Making Test (higher scores=worse performance).

Figure 1.

Cohen’s d effect size for the time-dependent effects of low dose hydrocortisone versus placebo on cognition in HIV-infected women.

Note. **p<0.01; *p<0.05. T=0.06. WM=working memory.

Among the cytokines examined, on average, LDH only changed IL-1β, MIF, and sCD14 (p’s<0.05). LDH increased IL-1β (B =0.14, SE=0.07, p=0.04) and decreased MIF (B =−0.27, SE=0.12, p=0.03) across time. LDH decreased sCD14 at the 30-minute time point (B=−1.98, SE=0.95, p=0.04).

Do individual differences in salivary cortisol and/or immune responsivity to LDH correlate with LDH-related cognitive improvements versus placebo?

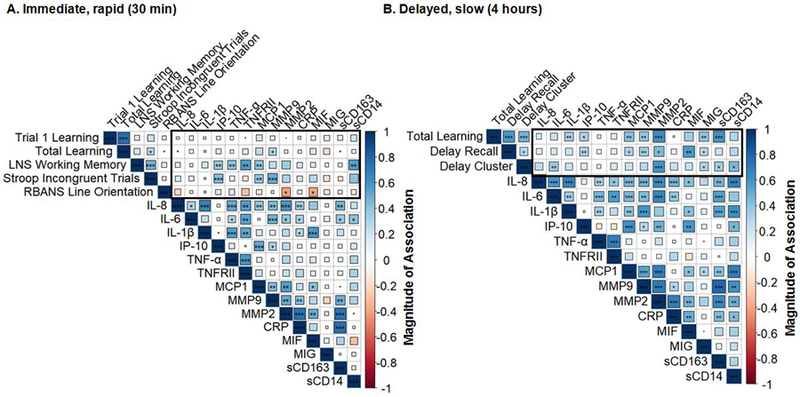

The magnitude of LDH-related salivary cortisol increases was not associated with cognitive improvements at the 30-minute time point and was only associated with improved performance on HVLT delayed recall at the 4-hour time point (Figure 2). LDH changes in immune markers were associated with cognitive improvements at both time points (Figure 3). At the 30-minute time point, greater LDH-induced reductions in IP-10, TNF-α, TNFRII, MCP1, MMP9, and sCD14 were associated with improvements in executive functioning (LNS working memory, Stroop incongruent trials; p’s<0.05). At the 4-hour time point, LDH-induced reductions in IL-6, IL-1β, IP-10, MCP1, MMP9, MMP2, MIF, MIG, and sCD163 were associated with HVLT improvements (learning, memory, and strategic retrieval; p’s<0.05).

Figure 2.

The magnitude of increase in salivary cortisol responsivity due to low dose hydrocortisone (LDH) is associated with verbal memory improvement (LHD – placebo) at the delayed, slow 4-hour time point but not at the immediate, rapid 30 minute time point.

Note. HVLT=Hopkins Verbal Learning Test.

Figure 3.

Raw correlations between immune responsivity and cognitive improvement due to low dose hydrocortisone (LDH) at the (A) immediate, rapid (30 min) and (B) delayed, slow (4 hour) time point.

Note. ***p<0.01; **p<0.05; *p<0.10. Immune responsivity calculated as placebo minus LDH; Cognitive improvement was calculated as LDH minus placebo. Thus, when the magnitude of the association is positive (blue) that means that the greater the reduction in inflammatory markers is associated with greater cognitive improvement with LDH. All women (n=36) had values for IL-8, IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α. 35 women had values for IP-10, MCP1, CRP, and MIG. 32 women had values for MMP9. 23 women had values for sCD163. 19 women had values for TNFRII. 18 women had values for MIF and MMP2. 17 women had values for sCD14. IL-8, IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, IP-10, MCP1, CRP, MIG, and MMP9 were part of the original panel of markers; thus missing values on these immune markers reflects sample availability. sCD163, sCD14, TNFRII, MIF, and MMP2 were added as the study progressed and thus not all women have these markers.

Discussion

Our primary goal was to examine the cognitive effects of LDH versus placebo in HIV-infected women. In our within-subjects design, we found that versus placebo, LDH had cognitive enhancing effects both 30 minutes and 4 hours after administration. At the 30-minute time point, LDH improved verbal learning and delayed memory, working memory, behavioral inhibition, and visuospatial abilities. LDH improvements on all of these abilities excluding working memory were larger than improvements due to practice and the effect sizes were generally small. The benefits of LDH on these abilities were only seen at the 30-minute time point suggesting a temporary, nongenomic mechanism. The benefits of LDH on verbal learning and delayed memory, as well as strategic retrieval, were also seen at the 4-hour time point. These effect sizes were medium, and were larger than any benefit due the practice. The enduring benefit on verbal learning and delayed memory suggests a genomic mechanism that is maintained after cortisol levels return to baseline[25–27, 75]. Notably, the findings at the 4 hour time point indicate specificity of benefits to cognitive domains subserved by the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, brain regions abundant with GC receptors. Altogether, the pattern of findings suggests that LDH might enhance verbal learning and delayed memory in HIV-infected women through genomic effects on GC receptors in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Supporting this view, a functional magnetic resonance imaging study showed that hippocampal and prefrontal function is altered during a memory encoding task 180 minutes after LDH administration[26].

In addition to the GC effects on the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, the acute and delayed cognitive enhancing effects of LDH among HIV-infected women appear to be in part due to LDH-induced reductions in inflammation and for delayed memory were also due to cortisol responsivity. At the 30-minute time point, LDH-induced reductions in 6 of 14 immune markers (43%) including IP-10, TNF-α, TNFRII, MCP1, MMP9, and sCD14 were associated with LDH-induced enhancements in executive function. At the 4-hour time point, LDH-induced reductions in 9 out of 14 immune markers (64%) including IL-6, IL-1β, IP-10, MCP1, MMP9, MMP2, MIF, MIG, and sCD163 were associated with LDH-induced enhancements in verbal learning, delayed memory, and strategic retrieval. GCs are known to alter a number of cytokines including the ones that changed with LDH administration in the present study—IL-1β, IL-8, MIF, and sCD14 [76–78]. While immune changes were associated with cognitive changes, changes in cortisol generally were not; the exception was that increased cortisol responsivity was associated with improved delayed verbal memory at the 4-hour time point. Therefore, it appears that individual differences in cognitive response to LDH were strongly related to individual differences in immune response to LDH, but more weakly associated with individual differences in cortisol levels.

Our findings of a beneficial effect of LDH versus placebo in HIV-infected women may not be specific to HIV but rather may be due to the participants’ psychological status. Participants reported elevated childhood trauma, exposure to interpersonal violence, above-average levels of perceived stress [74] and depressive symptoms. In PTSD, LDH has also been shown to have acute (between 30 and 75 minutes) enhancing effects on verbal episodic, declarative, autobiographical, and working memory[38–41] that appear to be related to alterations in limbic-prefrontal connections[39, 79] possibly in a sex-dependent manner[79]. In contrast, healthy individuals often demonstrate negative effects of acute LDH treatment on declarative memory[31] and individuals with depression show no positive or negative benefit of LDH on autobiographical verbal or working memory[36, 37]. Larger scale-studies are needed to examine the modulatory effects of these factors on the impact of LDH on cognition among HIV-infected women.

The pattern and potential mechanisms underlying the cognitive effects of LDH in HIV-infected women differed from our findings in HIV-infected men[29]. Using the same procedures in HIV-infected men, we found that LDH only improved verbal learning at the 30-minute time point – a benefit associated with individual differences in LDH-induced changes in cortisol levels[29]. In the present study, LDH-induced increases in cortisol were associated with improvements in delayed memory, whereas no such relationship was observed in our prior study in men. While these findings regarding sex differences are preliminary and in need of replication, there are known sex differences in HPA axis activity[42, 43], in the association between cortisol and memory [80, 81], and in the cognitive response to stressor-induced increases in cortisol (women more sensitive[82])[80, 81, 83]. Sex differences in immune function in HIV[84–86] including monocyte-driven inflammatory biomarkers are also reported[87–91]. There are bidirectional influences of HPA axis and immune function[9, 10], but the effects of HIV and sex on these influences have not yet been elucidated. It is also important to consider sex differences in trauma exposure, mental health, and substance use[29], as HIV-infected women were more likely to report psychological risk factors but less likely to smoke, use cannabis, and have a history of alcohol use disorders versus our sample of HIV-infected men.

The study has a number of limitations including the relatively small number of women and number of exploratory statistical comparisons. Additionally, we did not assess baseline cognitive status. As in other LDH studies, we included current smokers but had them refrain from smoking the day of appointments. Nicotine withdrawal can induce increases in GC levels and changes in HPA axis sensitivity[92, 93], but adjusting for smoking did not change our results. As in many HIV studies we included cannabis users, which is another substance that can alter HPA axis responsivity[94] but again adjusting for cannabis use did not change our results. Larger studies are needed to understand the impact of these substances in the context of HIV and whether they moderate the impact of LDH on cognition.

In sum, administration of LDH in HIV-infected women enhanced a number of cognitive abilities acutely and in the longer term. The finding of cognitive benefits in HIV-infected women at the delayed time point, when cortisol levels returned to baseline, indicates that targeting the HPA axis may have utility for treating cognitive impairments in HIV-infected women. Larger studies are needed to verify the cognitive-enhancing effects of LDH, to determine whether effects are observed with extended daily use of LDH, to verify the genomic and immune mechanisms contributing to LDH-induced cognitive enhancements, and to understand the factors that determine cognitive response to LDH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers K01MH098798 (Rubin) and R21MH099978 (Rubin). The project described was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1TR000050. This project was also supported in part by a University of Illinois at Chicago Campus Review Board (CRB) Grant (Rubin) and a Chicago Developmental Center for AIDS Research pilot grant. We would like to thank Bruni Hirsch, Alana Aziz-Bradley, Jacob Ellis, Sheila D’Sa, Shannon Dowty, Lauren Drogos, Lacey Wisslead, Aleksa Anderson, and Preet Dhillon for their assistance with this study and Raha Dastgheyb for help with creating Figure 3. We would also like to thank Kathleen Weber and the CORE Center at John H. Stroger Jr Hospital of Cook County for help in recruiting participants to the present study. We would also like to thank all of our participants, for without you this work would not be possible.

Study Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers K01MH098798 (Rubin) and R21MH099978 (Rubin). The project described was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1TR000050. This project was also supported in part by a University of Illinois at Chicago Campus Review Board (CRB) Grant (Rubin) and a Chicago Developmental Center for AIDS Research pilot grant. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Contributors

Drs. Rubin, Phan, and Maki conceived the study idea. Dr. Rubin provided oversight as principal investigator of the study. Dr. Rubin is responsible for the ascertainment of biospecimens (saliva, blood) and the integrity of cognitive, behavioral, and clinical data. Dr. Rubin also conducted the statistical analyses. Dr. Keating takes responsibility for the integrity of the immune data and analyses. Drs. Rubin and Maki wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

References

- 1.D’Aversa TG, Eugenin EA, Berman JW. NeuroAIDS: contributions of the human immunodeficiency virus-1 proteins Tat and gp120 as well as CD40 to microglial activation. J Neurosci Res 2005; 81(3):436–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burdo TH, Lackner A, Williams KC. Monocyte/macrophages and their role in HIV neuropathogenesis. Immunological reviews 2013; 254(1):102–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magarinos AM, Somoza G, De Nicola AF. Glucocorticoid negative feedback and glucocorticoid receptors after hippocampectomy in rats. Horm Metab Res 1987; 19(3):105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diorio D, Viau V, Meaney MJ. The role of the medial prefrontal cortex (cingulate gyrus) in the regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress. J Neurosci 1993; 13(9):3839–3847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meaney MJ, Aitken DH. [3H]Dexamethasone binding in rat frontal cortex. Brain Res 1985; 328(1):176–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McEwen BS, De Kloet ER, Rostene W. Adrenal steroid receptors and actions in the nervous system. Physiol Rev 1986; 66(4):1121–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez MM, Young LJ, Plotsky PM, Insel TR. Distribution of corticosteroid receptors in the rhesus brain: relative absence of glucocorticoid receptors in the hippocampal formation. J Neurosci 2000; 20(12):4657–4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valdez A, Rubin LH, Neigh GN. Untangling the Gordian knot of HIV, stress, and cognitive impairment. Neurobiology of Stress 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman MN, Sternberg EM. Glucocorticoid regulation of inflammation and its functional correlates: from HPA axis to glucocorticoid receptor dysfunction. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012; 1261:55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverman MN, Pearce BD, Biron CA, Miller AH. Immune modulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis during viral infection. Viral Immunol 2005; 18(1):41–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biglino A, Limone P, Forno B, Pollono A, Cariti G, Molinatti GM, et al. Altered adrenocorticotropin and cortisol response to corticotropin-releasing hormone in HIV-1 infection. Eur J Endocrinol 1995; 133(2):173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verges B, Chavanet P, Desgres J, Vaillant G, Waldner A, Brun JM, et al. Adrenal function in HIV infected patients. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1989; 121(5):633–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enwonwu CO, Meeks VI, Sawiris PG. Elevated cortisol levels in whole saliva in HIV infected individuals. Eur J Oral Sci 1996; 104(3):322–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lortholary O, Christeff N, Casassus P, Thobie N, Veyssier P, Trogoff B, et al. Hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal function in human immunodeficiency virus-infected men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996; 81(2):791–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christeff N, Gherbi N, Mammes O, Dalle MT, Gharakhanian S, Lortholary O, et al. Serum cortisol and DHEA concentrations during HIV infection. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1997; 22 Suppl 1:S11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chittiprol S, Kumar AM, Shetty KT, Kumar HR, Satishchandra P, Rao RS, et al. HIV-1 clade C infection and progressive disruption in the relationship between cortisol, DHEAS and CD4 cell numbers: a two-year follow-up study. Clin Chim Acta 2009; 409(1–2):4–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar M, Kumar AM, Morgan R, Szapocznik J, Eisdorfer C. Abnormal pituitary-adrenocortical response in early HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1993; 6(1):61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rondanelli M, Solerte SB, Fioravanti M, Scevola D, Locatelli M, Minoli L, et al. Circadian secretory pattern of growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor type I, cortisol, adrenocorticotropic hormone, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and prolactin during HIV infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 1997; 13(14):1243–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steptoe A, Hamer M, Chida Y. The effects of acute psychological stress on circulating inflammatory factors in humans: a review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 2007; 21(7):901–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen RA, de la Monte S, Gongvatana A, Ombao H, Gonzalez B, Devlin KN, et al. Plasma cytokine concentrations associated with HIV/hepatitis C coinfection are related to attention, executive and psychomotor functioning. J Neuroimmunol 2011; 233(1–2):204–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Correia S, Cohen R, Gongvatana A, Ross S, Olchowski J, Devlin K, et al. Relationship of plasma cytokines and clinical biomarkers to memory performance in HIV. Journal of Neuroimmunology 2013; 265(1–2):117–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubin LH, Benning L, Keating SM, Norris PJ, Burke-Miller J, Savarese A, et al. Variability in C-reactive protein is associated with cognitive impairment in women living with and without HIV: a longitudinal study. J Neurovirol 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imp BM, Rubin LH, Tien PC, Plankey MW, Golub ET, French AL, et al. Monocyte Activation Is Associated With Worse Cognitive Performance in HIV-Infected Women With Virologic Suppression. J Infect Dis 2017; 215(1):114–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller R, Plessow F, Kirschbaum C, Stalder T. Classification criteria for distinguishing cortisol responders from nonresponders to psychosocial stress: evaluation of salivary cortisol pulse detection in panel designs. Psychosom Med 2013; 75(9):832–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henckens MJ, van Wingen GA, Joels M, Fernandez G. Time-dependent effects of corticosteroids on human amygdala processing. J Neurosci 2010; 30(38):12725–12732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henckens MJ, Pu Z, Hermans EJ, van Wingen GA, Joels M, Fernandez G. Dynamically changing effects of corticosteroids on human hippocampal and prefrontal processing. Human brain mapping 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henckens MJ, van Wingen GA, Joels M, Fernandez G. Time-dependent corticosteroid modulation of prefrontal working memory processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108(14):5801–5806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henckens MJ, van Wingen GA, Joels M, Fernandez G. Time-dependent effects of cortisol on selective attention and emotional interference: a functional MRI study. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience 2012; 6:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubin LH, Phan KL, Keating SM, Weber KM, Maki PM. Low dose hydrocortisone has acute enhancing effects on verbal learning in HIV-infected men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schilling TM, Kolsch M, Larra MF, Zech CM, Blumenthal TD, Frings C, et al. For whom the bell (curve) tolls: cortisol rapidly affects memory retrieval by an inverted U-shaped dose-response relationship. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013; 38(9):1565–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Het S, Ramlow G, Wolf OT. A meta-analytic review of the effects of acute cortisol administration on human memory. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005; 30(8):771–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lupien SJ, Fiocco A, Wan N, Maheu F, Lord C, Schramek T, et al. Stress hormones and human memory function across the lifespan. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005; 30(3):225–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolf OT. Stress and memory in humans: twelve years of progress? Brain Res 2009; 1293:142–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandi C, Pinelo-Nava MT. Stress and memory: behavioral effects and neurobiological mechanisms. Neural Plast 2007; 2007:78970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Domes G, Rothfischer J, Reichwald U, Hautzinger M. Inverted-U function between salivary cortisol and retrieval of verbal memory after hydrocortisone treatment. Behav Neurosci 2005; 119(2):512–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schlosser N, Wolf OT, Fernando SC, Riedesel K, Otte C, Muhtz C, et al. Effects of acute cortisol administration on autobiographical memory in patients with major depression and healthy controls. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2010; 35(2):316–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Terfehr K, Wolf OT, Schlosser N, Fernando SC, Otte C, Muhtz C, et al. Hydrocortisone impairs working memory in healthy humans, but not in patients with major depressive disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011; 215(1):71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yehuda R, Harvey PD, Buchsbaum M, Tischler L, Schmeidler J. Enhanced effects of cortisol administration on episodic and working memory in aging veterans with PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology 2007; 32(12):2581–2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yehuda R, Harvey PD, Golier JA, Newmark RE, Bowie CR, Wohltmann JJ, et al. Changes in relative glucose metabolic rate following cortisol administration in aging veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: an FDG-PET neuroimaging study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2009; 21(2):132–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wingenfeld K, Driessen M, Terfehr K, Schlosser N, Fernando SC, Otte C, et al. Cortisol has enhancing, rather than impairing effects on memory retrieval in PTSD. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wingenfeld K, Driessen M, Schlosser N, Terfehr K, Carvalho Fernando S, Wolf OT. Cortisol effects on autobiographic memory retrieval in PTSD: an analysis of word valence and time until retrieval. Stress 2013; 16(5):581–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kajantie E, Phillips DI. The effects of sex and hormonal status on the physiological response to acute psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2006; 31(2):151–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kudielka BM, Kirschbaum C. Sex differences in HPA axis responses to stress: a review. Biol Psychol 2005; 69(1):113–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Webster JI, Tonelli L, Sternberg EM. Neuroendocrine regulation of immunity. Annual review of immunology 2002; 20:125–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rohleder N, Wolf JM, Kirschbaum C. Glucocorticoid sensitivity in humans-interindividual differences and acute stress effects. Stress 2003; 6(3):207–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bernstein D, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective self-report. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Coorporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bieliauskas L, Counte M, Glandon G. Inventorying stressing life events as related to health change in the elderly. Stress Medicine 1995; 11(93–103). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruggiero KJ, Del Ben K, Scotti JR, Rabalais AE. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version. J Trauma Stress 2003; 16(5):495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983; 24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1977; 1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Hoch CC, Yeager AL, Kupfer DJ. Quantification of subjective sleep quality in healthy elderly men and women using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Sleep 1991; 14(4):331–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walsh JC, Mandalia S, Gazzard BG. Responses to a 1 month self-report on adherence to antiretroviral therapy are consistent with electronic data and virological treatment outcome. AIDS 2002; 16(2):269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petrovsky N, McNair P, Harrison LC. Diurnal rhythms of pro-inflammatory cytokines: regulation by plasma cortisol and therapeutic implications. Cytokine 1998; 10(4):307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petrovsky N, Harrison LC. The chronobiology of human cytokine production. International reviews of immunology 1998; 16(5–6):635–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stalder T, Kirschbaum C, Kudielka BM, Adam EK, Pruessner JC, Wust S, et al. Assessment of the cortisol awakening response: Expert consensus guidelines. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016; 63:414–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Benedict RHB, Schretlen D, Groninger L, Brandt J. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test - Revised: Normative Data and Analysis of Inter-Form and Test-Retest Relability. The Clinical Neuropsychologist 1998; 12(43–55v). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 4 San Antonio, TX: Pearson; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reitan R. Manual for Administration of Neuropsychological Test Batteries for Adults and Children. Tuscon, AZ: Neuropsychology Laboratories, Inc.; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 59.MacLeod CM. Half a century of research on the Stroop effect: an integrative review. Psychol Bull 1991; 109(2):163–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Benton AL, Hamsher K., Varney NR, Spreen O. Judgment of line orientation. Oxford University Press, Inc.; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Benedict RH, Zgaljardic DJ. Practice effects during repeated administrations of memory tests with and without alternate forms. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1998; 20(3):339–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wagner S, Helmreich I, Dahmen N, Lieb K, Tadic A. Reliability of three alternate forms of the trail making tests a and B. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2011; 26(4):314–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beglinger LJ, Gaydos B, Tangphao-Daniels O, Duff K, Kareken DA, Crawford J, et al. Practice effects and the use of alternate forms in serial neuropsychological testing. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2005; 20(4):517–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Burdo TH, Weiffenbach A, Woods SP, Letendre S, Ellis RJ, Williams KC. Elevated sCD163 in plasma but not cerebrospinal fluid is a marker of neurocognitive impairment in HIV infection. AIDS 2013; 27(9):1387–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Royal W 3rd, Cherner M, Burdo TH, Umlauf A, Letendre SL, Jumare J, et al. Associations between Cognition, Gender and Monocyte Activation among HIV Infected Individuals in Nigeria. PLoS One 2016; 11(2):e0147182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oikonomidi A, Tautvydaite D, Gholamrezaee MM, Henry H, Bacher M, Popp J. Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor is Associated with Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology and Predicts Cognitive Decline in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Mild Dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 2017; 60(1):273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Popp J, Bacher M, Kolsch H, Noelker C, Deuster O, Dodel R, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. J Psychiatr Res 2009; 43(8):749–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li Q, Michaud M, Shankar R, Canosa S, Schwartz M, Madri JA. MMP-2: A modulator of neuronal precursor activity and cognitive and motor behaviors. Behav Brain Res 2017; 333:74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weekman EM, Wilcock DM. Matrix Metalloproteinase in Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown in Dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 2016; 49(4):893–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marteau TM, Bekker H. The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Br J Clin Psychol 1992; 31 ( Pt 3):301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stacey AR, Norris PJ, Qin L, Haygreen EA, Taylor E, Heitman J, et al. Induction of a striking systemic cytokine cascade prior to peak viremia in acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection, in contrast to more modest and delayed responses in acute hepatitis B and C virus infections. J Virol 2009; 83(8):3719–3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pruessner JC, Kirschbaum C, Meinlschmid G, Hellhammer DH. Two formulas for computation of the area under the curve represent measures of total hormone concentration versus time-dependent change. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003; 28(7):916–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992; 112(1):155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cohen S, Williamson GM. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States In: The Social Psychology of Health. Spacapan S, Oskamp S (editors). Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Henckens MJ, Hermans EJ, Pu Z, Joels M, Fernandez G. Stressed memories: how acute stress affects memory formation in humans. J Neurosci 2009; 29(32):10111–10119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nockher WA, Scherberich JE. Expression and release of the monocyte lipopolysaccharide receptor antigen CD14 are suppressed by glucocorticoids in vivo and in vitro. J Immunol 1997; 158(3):1345–1352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brattsand R, Linden M. Cytokine modulation by glucocorticoids: mechanisms and actions in cellular studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1996; 10 Suppl 2:81–90; discussion 91–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Calandra T, Bucala R. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF): a glucocorticoid counter-regulator within the immune system. Crit Rev Immunol 1997; 17(1):77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ma ST, Abelson JL, Okada G, Taylor SF, Liberzon I. Neural circuitry of emotion regulation: Effects of appraisal, attention, and cortisol administration. Cognitive, affective & behavioral neuroscience 2017; 17(2):437–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Seeman TE, McEwen BS, Singer BH, Albert MS, Rowe JW. Increase in urinary cortisol excretion and memory declines: MacArthur studies of successful aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997; 82(8):2458–2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McCormick CM, Lewis E, Somley B, Kahan TA. Individual differences in cortisol levels and performance on a test of executive function in men and women. Physiol Behav 2007; 91(1):87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wolf OT, Schommer NC, Hellhammer DH, McEwen BS, Kirschbaum C. The relationship between stress induced cortisol levels and memory differs between men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2001; 26(7):711–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wolf OT, Kudielka BM, Hellhammer DH, Hellhammer J, Kirschbaum C. Opposing effects of DHEA replacement in elderly subjects on declarative memory and attention after exposure to a laboratory stressor. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1998; 23(6):617–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Alcaide ML, Parmigiani A, Pallikkuth S, Roach M, Freguja R, Della Negra M, et al. Immune activation in HIV-infected aging women on antiretrovirals--implications for age-associated comorbidities: a cross-sectional pilot study. PLoS One 2013; 8(5):e63804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Krebs SJ, Slike BM, Sithinamsuwan P, Allen IE, Chalermchai T, Tipsuk S, et al. Sex differences in soluble markers vary before and after the initiation of antiretroviral therapy in chronically HIV infected individuals. AIDS 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Meier A, Chang JJ, Chan ES, Pollard RB, Sidhu HK, Kulkarni S, et al. Sex differences in the Toll-like receptor-mediated response of plasmacytoid dendritic cells to HIV-1. Nat Med 2009; 15(8):955–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ticona E, Bull ME, Soria J, Tapia K, Legard J, Styrchak SM, et al. Biomarkers of inflammation in HIV-infected Peruvian men and women before and during suppressive antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2015; 29(13):1617–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fitch KV, Srinivasa S, Abbara S, Burdo TH, Williams KC, Eneh P, et al. Noncalcified coronary atherosclerotic plaque and immune activation in HIV-infected women. J Infect Dis 2013; 208(11):1737–1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Martin GE, Gouillou M, Hearps AC, Angelovich TA, Cheng AC, Lynch F, et al. Age-associated changes in monocyte and innate immune activation markers occur more rapidly in HIV infected women. PLoS One 2013; 8(1):e55279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mathad JS, Gupte N, Balagopal A, Asmuth D, Hakim J, Santos B, et al. Sex-Related Differences in Inflammatory and Immune Activation Markers Before and After Combined Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016; 73(2):123–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Looby SE, Fitch KV, Srinivasa S, Lo J, Rafferty D, Martin A, et al. Reduced ovarian reserve relates to monocyte activation and subclinical coronary atherosclerotic plaque in women with HIV. AIDS 2016; 30(3):383–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pickworth WB, Fant RV. Endocrine effects of nicotine administration, tobacco and other drug withdrawal in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1998; 23(2):131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Semba J, Wakuta M, Maeda J, Suhara T. Nicotine withdrawal induces subsensitivity of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis to stress in rats: implications for precipitation of depression during smoking cessation. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2004; 29(2):215–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.van Leeuwen AP, Creemers HE, Greaves-Lord K, Verhulst FC, Ormel J, Huizink AC. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis reactivity to social stress and adolescent cannabis use: the TRAILS study. Addiction 2011; 106(8):1484–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.