Abstract

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are formulated using unmodified cholesterol. However, cholesterol is naturally esterified and oxidized in vivo, and these cholesterol variants are differentially trafficked in vivo via lipoproteins including LDL and VLDL. We hypothesized that incorporating the same cholesterol variants into LNPs - which can be structurally similar to LDL and VLDL – would alter nanoparticle targeting in vivo. To test this hypothesis, we quantified how >100 LNPs made with 6 cholesterol variants delivered DNA barcodes to 18 cell types in wildtype, LDL R−/−, and VLDLR−/− mice that were both age-matched and female. By analyzing ~2,000 in vivo drug delivery data points, we found that LNPs formulated with esterified cholesterol delivered nucleic acids more efficiently than LNPs formulated with regular or oxidized cholesterol when compared across all tested cell types in the mouse. We also identified an LNP containing cholesteryl oleate that efficiently delivered siRNA and sgRNA to liver endothelial cells in vivo. Delivery was as - or more - efficient than the same LNP made with unmodified cholesterol. Moreover, delivery to liver endothelial cells was 3X more efficient than delivery to hepatocytes, distinguishing this oleate LNP from hepatocyte-targeting LNPs. RNA delivery can be improved by rationally selecting cholesterol variants, allowing optimization of nanoparticle targeting.

Keywords: DNA barcoded nanoparticles, cholesterol trafficking, cholesterol structure, drug delivery, gene editing, siRNA, nanotechnology

In vivo drug delivery is a complex process that is difficult to predict.1,2 The relationship between in vitro and in vivo delivery can be non-existent,3 demonstrating the utility of testing hundreds of nanoparticles in vivo.3 Recently, DNA barcode-based technologies have enabled scientists to study many nanoparticles in vivo simultaneously.3–5 Here we sought to improve nucleic acid delivery mediated by lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) by systematically studying the relationship between LNP chemical structure and in vivo delivery.

We focused on cholesterol variants in the LNP for several reasons. Many labs have studied how the structure of hundreds of cationic or ionizable lipid-like biomaterial in LNPs affects delivery in vitro;6–11 in vivo structure function studies using more than a few LNPs have not been published. LNPs are created (‘formulated’) by mixing these lipid-like biomaterials with other constituents, most often PEG-lipids12 and unmodified cholesterol. However, cholesterol is naturally oxidized or esterified in vivo. Oxidized cholesterol is typically found within oxidized LDL (ox-LDL). LDL oxidation is partially driven by diet, the presence of reactive oxygen species, and other factors.13 Esterification of cholesterol occurs at different sites (e.g. peripheral tissues, liver), enabling more compact storage and transportation of cholesterol.14 Esterification of cholesterol from peripheral tissues is mediated by lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase on the surface of nascent HDL, and by acyl-COA-cholesterol acyltransferase intracellularly.15,16 These cholesterol ‘variants’ are also actively trafficked to cells including hepatocytes, endothelial cells, and macrophages.14

The amount of different cholesterol variants also changes with many common diseases (e.g., high cholesterol, atherosclerosis, hyperlipidemia, diabetes),17 suggesting that LNP trafficking may change with the disease state of the patient. For instance, ox-LDL is pro-atherosclerotic, pro-inflammatory, and contributes to the amount of ROS in the bloodstream.18–21 Increases in ox-LDL are indicators of diseases such as atherosclerosis and heart disease.22–25 Despite these facts, the relationship between cholesterol structure and in vivo LNP delivery remains unexplored.

We hypothesized that the structure of cholesterol included in LNPs affects targeting in vivo. This hypothesis has important implications. It suggests LNP targeting can be tuned using naturally- or synthetically-derived cholesterol variants; this is critical given the need for LNPs that deliver RNAs to cell types other than hepatocytes.26 It also implies that LNPs may behave differently in patients with aberrant cholesterol levels. For instance, patients with aberrant metabolisms may have increased amounts of oxidative stress, leading to a higher presence of oxidized cholesterol, creating positive feedback.27 In patients with dyslipidemia, this positive feedback loop can start as a change in lipoprotein core structure, particularly a decrease in cholesteryl esters and cholesterol and an increased chance of oxidation.28 This is important given the growing clinical use of LNPs that deliver siRNAs29 and the high percentage of patients that have aberrant cholesterol levels. We tested our hypothesis in wild type mice as well as low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) and very low-density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) knockout mice. Both mouse models are regularly used to study cholesterol dysfunction.30,31 LDLR−/− and VLDLR−/− mice are typically given high fat diets to induce metabolic disease. Herein we examined nanoparticle delivery in strain- and age-matched wildtype (WT) controls for mice fed a normal diet, such that the only difference would be LDLR or VLDLR expression.

Other groups have studied the relationship between nanoparticles and gene expression32,33. Our current work complements these studies but is distinct. These studies used a small number of nanoparticles to test the hypothesis that a specific gene influenced nanoparticle delivery. By contrast, we used >100 LNPs to test hypothesis that cholesterol structure affected LNP delivery. We formulated 141 LNPs with 6 cholesterol variants based on natural lipoproteins. We administered all the LNPs in vivo at once to WT, LDLR−/−, or VLDLR−/− mice using high throughput LNP DNA barcoding,3,4 and isolated cells using fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). Using a nanoparticle bioinformatics pipeline, we found that LNPs formulated with esterified cholesterol increased LNP distribution relative to LNPs with regular or oxidized cholesterol in WT mice when averaging nanoparticle distribution across all cell types analyzed. Based on the in vivo screen, we identified an LNP enriched in hepatic endothelial cells. As predicted by the in vivo nanoparticle barcoding screen, the LNP efficiently delivered therapeutic acids to hepatic endothelial cells, which have been refractory to systemic nanoparticle targeting.

Results and Discussion

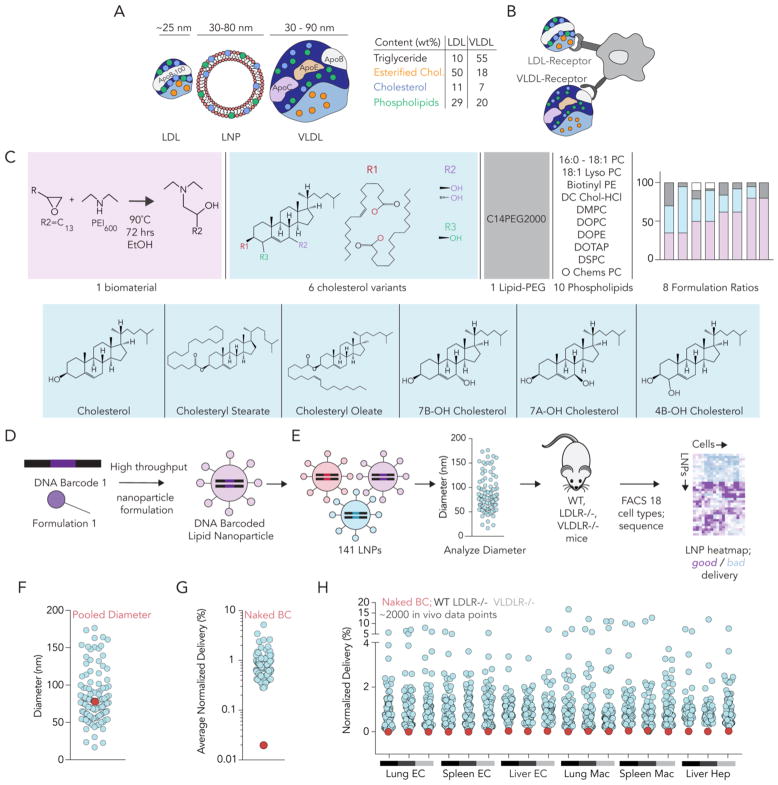

We used high throughput DNA barcoding3,4 to assess how cholesterol variants altered LNP biodistribution. LNPs can be made with a similar size and composition as LDL and VLDL (Fig 1A), two lipoproteins which interact with the LDLR and VLDLR (Fig 1B). We formulated 141 LNPs using esterified, oxidized, or unmodified cholesterol (Fig. 1C,D, Supplementary Fig. 1A). All LNPs were formulated using the validated biomaterial 7C1.6 Of the 141, 111 met our inclusion criteria: autocorrelation curves with 1 inflection point and hydrodynamic diameters between 20 nm and 200 nm, based on dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Fig. 1E–F, Supplementary Fig. 1B). These 111 LNPs – along with a naked DNA barcode, which served as a negative control - were pooled together and intravenously administered to WT, LDLR−/−, and VLDLR−/− mice at a total DNA dose of 0.5 mg/kg (0.0045 mg / kg / barcode). We sacrificed the mice 72 hours later and harvested DNA from lung endothelial cells (CD31+CD45−), lung macrophages (CD31−CD45+CD11b+), splenic endothelial cells, splenic macrophages, liver endothelial cells, and hepatocytes (CD31−CD45−) using FACS3,6,34–36 (Supplementary Fig. 1C–E). Seventy-two hours is sufficiently long for LNPs to be cleared from the bloodstream.6 All 3 cell types play critical roles in cholesterol trafficking. Macrophages are known to uptake oxidized cholesterol via scavenger receptor-mediated endocytosis of ox-LDL, one of the initial steps in the formation of foam cells which are critical to the progression of atherosclerosis37–39 Hepatocytes also play a critical role by synthesizing cholesterol in the liver and responding to internal increases or decreases in cholesterol by up or down-regulating production of LDLR.40,41 Finally, endothelial cells actively interact with serum lipoproteins to maintain cholesterol homeostasis.42,43 To assess how all LNPs delivered DNA at once, we amplified barcodes and deep sequenced them as we previously described3,4. The readout for these DNA sequencing experiments is normalized delivery,3 which is analogous to counts per million in RNA-seq experiments (Supplementary Fig. 1F).

Figure 1.

High throughput DNA barcoding can be used to test the hypothesis that cholesterol modifications influence LNP delivery in vivo. (A) LDL and VLDL particles share physical traits with LNPs, including composition and size. Notably, LDL and VLDL both contain unmodified cholesterol as well as modified cholesterol. (B) Cells naturally interact with (and traffic) LDL and VLDL, suggesting similar mechanisms may alter LNP targeting. (C) A diverse library of 141 LNPs was formulated using 6 cholesterol variants to test the hypothesis that cholesterol structure altered LNP delivery in vivo. (D) Each LNP was formulated to carry a distinct DNA barcode, before (E) stable LNPs were pooled together and administered to either WT, LDLR−/−, or VLDLR−/− mice. After isolating 6 cell types from each mouse, delivery mediated by all LNPs was measured concurrently using DNA sequencing. (F) Hydrodynamic diameter, measured by DLS, for all individual LNPs included, as well as the diameter of the LNP pool after mixing. (G,H) Normalized delivery for the negative control (naked barcode) - averaged across all 18 samples - was much lower than normalized delivery for all LNPs.

We first analyzed whether cholesterol structure affected LNP size. We measured the hydrodynamic diameter of all 111 LNPs individually. Oxidized, esterified, and unmodified cholesterol formulated LNPs that met our inclusion criteria 72–100%, 56–76%, and 80% of the time, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1G). Cholesteryl oleate had the lowest percent included LNPs and the tightest diameter distribution (22 – 115 nm) for cholesterol containing LNPs (Supplementary Fig. 1H). The average LNP diameter did not change with cholesterol type (Supplementary Fig. 1H). As an additional control for LNP size, we plotted normalized delivery against LNP diameter for all ~2,000 in vivo data points. The number of in vivo data points was calculated as shown in Supplementary Table 1. As we reported previously,3,4 we found no relationship between LNP size and delivery (Supplementary Fig. 1I). We then looked at whether this relationship improved if we split the LNPs by cholesterol variant and then plotted normalized delivery against LNP diameter (Supplementary Fig. 1J–P). We did not observe an improvement in the R2 value, suggesting that there was no trend between LNP size distribution and normalized delivery when breaking up the LNPs by cholesterol variant (Supplementary Fig. 1Q). The diameter of the pooled LNPs was similar to the diameters of the individual LNPs (Fig. 1F). We also analyzed the delivery of naked barcode; as expected, this negative control was delivered much less efficiently than barcodes delivered by LNPs in all 18 samples (Fig. 1G,H).

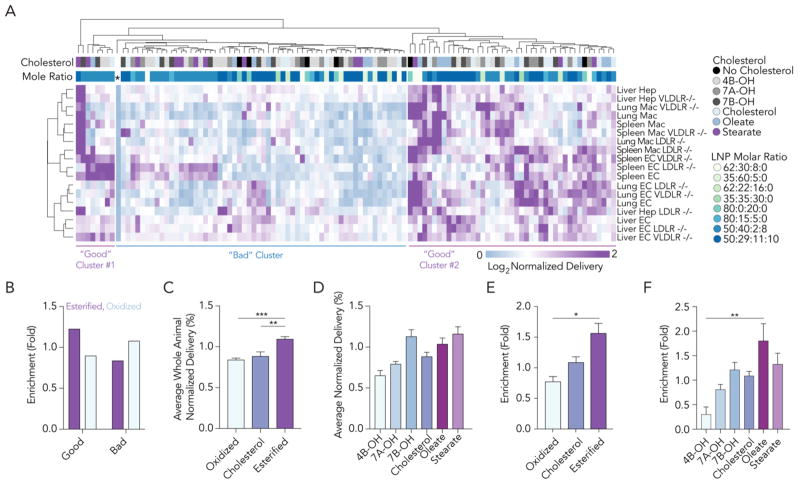

To assess how cholesterol structure affected delivery in vivo for all LNPs, we used unbiased Euclidian analysis to generate a nanoparticle targeting heatmap (Fig. 2A). Euclidean analysis is a common bioinformatics approach44 that ‘clusters’ large data sets into experimental groups which behave similarly; it can be used to study barcoded LNPs.3 The naked barcode – designated by an asterisk – was easily identified; it delivered barcodes inefficiently in all samples. Euclidean analysis created 3 clusters; when compared to the ‘center’ cluster, the left- and right-most clusters had more purple, which designated higher normalized delivery (Fig. 2A). Based on this data visualization, we analyzed the cholesterol types in the left- and right-most (i.e. ‘good’) clusters, and the center (i.e. ‘bad’) cluster. LNPs formulated with esterified cholesterols were 1.4-fold enriched in the good clusters, relative to LNPs made with oxidized cholesterol. In other words, LNPs formulated with esterified cholesterols were 1.4-fold more likely to be in the left- or rightmost clusters than oxidized cholesterols. LNPs made with oxidized cholesterols were enriched by 1.3-fold in the center cluster (Fig. 2B). Enrichment is described in Supplementary Fig. 2A. Based on these analyses, we quantified normalized barcode delivery mediated by nanoparticles that contained esterified, unmodified, or oxidized cholesterols in all cell types in WT mice. Normalized barcode delivery mediated by LNPs made with esterified cholesterol was significantly higher than barcode delivery mediated by LNPs with regular cholesterol or oxidized cholesterol (Fig 2C,D, Supplementary Table 2). These analyses averaged delivery of each nanoparticle, including those that delivered barcodes inefficiently, across all cell types. However, many studies focus on top performing LNPs. We identified LNPs in the top 15% in each cell type and performed an enrichment analysis as described in Supplementary Fig. 2A. LNP formulations that were enriched in each cell type in WT, VLDLR−/−, and LDLR−/− mice are listed in Supplementary Fig. 2B–D. We then analyzed whether particle size and biodistribution in top performing LNPs were correlated and found no significant relationship between the two (Supplementary Fig. 2E–K). We performed this analysis for the whole animal (i.e., all cell types, averaged); esterified cholesterol was consistently enriched in the top 15%. LNPs formulated with esterified cholesterols were 2-fold more likely to be in the top 15% of LNPs than LNPs made with oxidized cholesterols in WT mice (Fig. 2E, F). Taken together, these data support the hypothesis that cholesterol structure affects LNP delivery in vivo.

Figure 2.

LNPs made with esterified cholesterol outperform LNPs made with oxidized cholesterol in vivo. (A) A nanoparticle targeting heatmap depicting normalized delivery generated by unbiased Euclidean clustering. This dataset contains nearly 2,000 in vivo drug delivery data points. The negative control (*) performed worse than all LNPs. LNP delivery was divided into 3 horizontal clusters. Lung, liver, and spleen endothelial cells (ECs), lung and spleen macrophages (Macs) and liver hepatocytes (Hep) are clustered vertically. (B) Enrichment of esterified and oxidized cholesterols in the left- / right-most (good) clusters and center-most (bad) cluster. LNPs made with esterified and oxidized cholesterol were more likely to be found in good and bad clusters, respectively. (C,D) Normalized delivery for all LNPs in WT mice, subdivided by the cholesterol type. (E,F) Enrichment in the top 15% of LNPs, subdivided by the cholesterol type. *p>0.0332, **p<0.0021, ***p<0.0002, 1-way ANOVA.

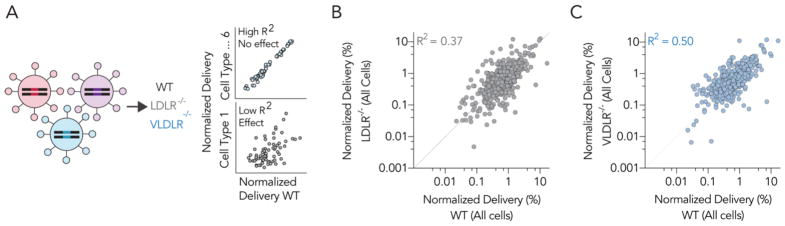

We performed the same analyses described above (Fig. 2C–F) for LDLR−/− and VLDLR−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 2L–S). Mimicking results in WT mice, oxidized cholesterols performed poorly relative to esterified and unmodified cholesterol in both knockout models when quantified using average normalized delivery and enrichment. Esterified cholesterol and unmodified cholesterol performed similarly when quantified using average normalized delivery. Enrichment in the top 15% varied; esterified cholesterol outperformed unmodified cholesterol in LDLR−/− mice, but not in VLDLR−/− mice. These results support previously published data demonstrating the cholesterol trafficking receptors can affect LNP delivery.32 Based on these initial analyses, we quantified the extent to which LNP delivery in LDLR−/− and VLDLR−/− mice differed from LNP delivery in WT mice. We plotted normalized delivery for all LNPs in all 6 cell types in WT, LDLR−/−, and VLDLR−/− mice (Fig. 3A). If either gene affected delivery of the LNP library tested, then the R2 value between the WT and knockout mice would decrease (Fig. 3A). The high throughput nature of barcoding enabled us to compare WT and knockout mice rigorously; each plot contains >650 in vivo data points (Fig. 3B,C). We found that both LDLR and VLDLR affected delivery; the R2 values between WT and either LDLR−/− or VLDLR−/− mice was 0.37 and 0.50, respectively. We then evaluated whether there was a cell type-specific effect to these genes by analyzing the R2 values between WT and LDLR−/− (Supplementary Fig. 3A–F) or VLDLR−/− (Supplementary Fig. 3G–L) mice for each of the 6 cell types individually. We did not observe clear patterns; the cell type specific effects of these genes on LNP delivery will need to be explored using different approaches in the future. values strongly suggest that both genes affect LNP targeting in vivo, and that LDLR affects delivery slightly more than VLDLR.

Figure 3.

LDLR and VLDLR affect LNP in vivo delivery globally. (A) To quantify the extent to which LDLR and VLDLR influenced LNP delivery, we quantified the correlation between delivery for all LNPs in all 6 cell types (>650 data points per mouse model). Normalized delivery in (B) LDLR−/− and (C) VLDLR−/− knockout mice plotted against normalized delivery in WT mice. The R2

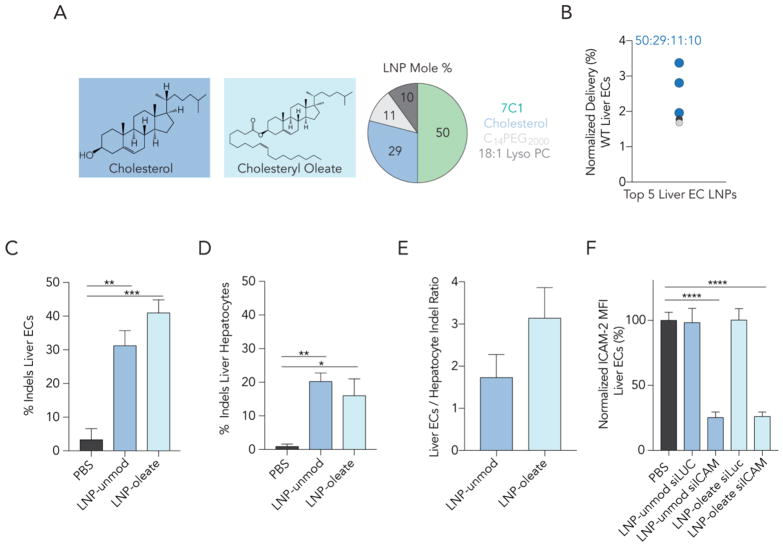

DNA barcode readouts quantify nanoparticle biodistribution, which is required, but not sufficient, for functional RNA delivery into the cytoplasm. Cytoplasmic RNA delivery is necessary for successful RNA-interference as well as gene editing. RNA mediated in vivo genome editing is important for studying biological pathways and understanding the potential differential effects that genes have on different cell types. To analyze whether LNPs formulated with esterified cholesterols functionally delivered RNAs in vivo, we selected an LNP for further analysis. To directly compare esterified cholesterol and unmodified cholesterol – which is the current gold standard in the field - we chose an LNP molar ratio (Fig. 4A) that made up 3 of the top 5 LNPs in hepatic endothelial cells in our barcoding screen (Fig. 4B). Hepatic endothelial cells have – with few exceptions45 – been difficult to target systemically, and as a result, have not been edited by Cas9 after systemic administration of single guide RNAs (sgRNAs). We formulated 2 LNPs with a 50: 29: 11: 10 molar ratio of 7C1, cholesterol, C14PEG2000, and 18:1 Lyso PC, respectively. LNP-oleate contained cholesteryl oleate, whereas LNP-unmod contained unmodified cholesterol. This molar ratio resulted in small, stable LNPs when formulated to carry siRNA and sgRNA (Supplementary Fig. 4A). We considered formulating LNPs with cholesteryl stearate, however, LNPs formulated with stearate were stable less frequently (Supplementary Fig. 1H).

Figure 4.

LNPs formulated with cholesteryl oleate deliver therapeutic RNAs as – or more – efficiently than LNPs formulated with unmodified cholesterol. (A,B) Based on the DNA barcoding screen, LNPs with a 50:29:11:10 molar ratio of 7C1: cholesterol: C14PEG2000: 18:1 Lyso PC were highly enriched in hepatic endothelial cells. We formulated 2 LNPs with this molar ratio; LNP-oleate contained cholesteryl oleate, where LNP-unmod contained unmodified cholesterol, the current gold standard in the field. (C–D) Indel percentage from (C) hepatic endothelial cells and (D) hepatocytes isolated 5 days after a single intravenous injection of either LNP-oleate or LNP-unmod. (E) Interestingly, LNP-oleate delivery led to 3X more editing in hepatic ECs relative to hepatocytes. (F) ICAM-2 MFI 3 days after an injection of PBS (control) siRNA targeting Luciferase (control) or siICAM-2. Robust ICAM-2 protein silencing was observed in siICAM-2 treated mice, but not siLuc treated mice. * p< 0.0332, **p<0.0021, ***p<0.0002, ****p<0.0001, 1-way ANOVA.

We formulated LNP-oleate and LNP-unmod to carry a chemically modified46 sgRNA targeting GFP (Supplementary Fig. 4B) and injected these nanoparticles intravenously into mice that express SpCas9-P2A-GFP under a CAG promoter. Five days after a 1.0 mg / kg sgRNA injection, we isolated hepatic endothelial cells and hepatocytes using FACS and quantified insertions and deletions (‘indels’) using Tracking Indels with DEcomposition (TIDE).47 Delivery to hepatic endothelial cells was highly efficient, leading to 41% editing at the target GFP locus (Fig. 4C). LNP-unmod was efficient (31% indels), but less so than LNP-oleate. Oleate delivery was particularly specific; the indel ratio of hepatic endothelial cells: hepatocytes was 3 (Fig. 4D,E). By contrast, all previous systemically administered nanoparticle gene editing has occurred preferentially in hepatocytes.46,48–50 This is the first report of sgRNA-mediated in vivo editing in hepatic endothelial cells.

We assessed the activity of LNP-oleate and LNP-unmod using siRNA. siRNA-based therapeutics have successfully treated disease in hepatocytes; understanding how to target hepatic endothelial cells has the potential to lead to therapeutics that target endothelial cell driven disease. We intravenously injected WT mice with 1.5 mg / kg siRNA targeting the endothelial specific gene ICAM-2 (Supplementary Fig. 4C). Both siICAM-2 and the control siRNA targeting Luciferase (siLuc) were chemically modified to reduce immune stimulation and promote on-target activity.6,34,35 Three days after siICAM-2 treatment with LNP-oleate or LNP-unmod, ICAM-2 protein expression, measured by mean fluorescent intensity (MFI), decreased by 74% and 75% respectively, in hepatic endothelial cells, compared to PBS- and siLuc-treated mice (Fig. 4F). Following treatment, mice injected with sgRNA or siRNA gained weight as quickly as PBS-treated mice (Supplementary Fig. 4D,E).

Conclusion

Despite being a universal problem that limits all genetic therapies,51–54 it is still difficult to predict which nanoparticles will deliver RNAs in vivo. Here we demonstrated that in vivo screening can be used to identify LNP traits that affect delivery. Our study was powered by strong statistical analyses; we compared nearly 2,000 in vivo drug delivery data points. These data support the hypothesis that modified cholesterols can affect nanoparticle targeting.

We identified an LNP formulation that efficiently targeted hepatic endothelial cells in vivo. The LNP preferentially delivered sgRNAs to hepatic endothelial cells 3X more efficiently than hepatocytes. This is uncommon; almost all reported LNPs preferentially target hepatocytes.7–12,46,48–50 Targeting hepatic endothelial cells is important given the active role they play in establishing the liver microenvironment and driving fibrosis, inflammation, primary tumor growth, and metastasis.55 Although we do not know the mechanism for preferential targeting to hepatic endothelial cells over hepatocytes, literature suggests that LNPs interact with serum proteins, which may promote delivery to specific cell types. We anticipate future studies utilizing LNP-oleate to treat hepatic endothelial cell disease and study fundamental biological questions related to hepatic endothelial cell signaling. More generally, our data demonstrate that cholesterol can be viewed as another modular LNP component that can be rationally designed to improve in vivo delivery, demonstrating that DNA barcoding is a powerful tool that can identify material properties that influence nanoparticle delivery in vivo.

This study complements previous in vitro work relating siRNA delivery to the structure of the cationic or ionizable lipid-like compound.6–10 This work also supports the idea that LNPs can be rationally designed with cholesterol structures that closely mimic natural LDL, HDL, or VDLR to improve delivery,56 or rationally designed to interact with natural cholesterol trafficking pathways. Given that cholesterol trafficking is perturbed in many diseases and as a side effect of commonly prescribed drugs,17 this also suggests that the efficacy of a LNP may vary with the patient population. One important limitation to this work is that the mechanism by which delivery of LNPs with esterified cholesterol is improved remains unclear. We hypothesize that this effect is mediated by differential interactions with serum proteins and the protein corona.57 Future studies detailing changes in target cell signaling and protein coronas will be required to confirm or disprove this proposed mechanism.

Methods/Experimental

Nanoparticle Formulation

Nanoparticles were formulated in a microfluidic device by mixing DNA with 7C1, PEG, cholesterol, and a helper lipid, as previously described.4,6,34–36,58–62 Nanoparticles were made with variable mole ratios of these constituents. The nucleic acid (e.g. DNA barcode, siRNA, sgRNA) was diluted in 10 mM citrate buffer (Teknova) and loaded into a syringe (Hamilton Company). The materials making up the nanoparticle (7C1, cholesterol, PEG, and helper lipid) were diluted in 100% ethanol, and loaded into a second syringe. The citrate phase and ethanol phase were mixed together in a microfluidic device at 600 uL/min and 200 uL/min, respectively. Helper lipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids.

DNA barcoding

Each chemically distinct LNP was formulated to carry its own distinct DNA barcode (Fig. 1A, B). For example, LNP1 carried DNA barcode 1, while the chemically distinct LNP2 carried DNA barcode 2. The DNA barcodes (IDT) were designed rationally with universal primer sites and an 8 nucleotide barcode sequence, similar to what we previously described3,4. Three nucleotides on the 5’ and 3’ ends were modified with phosphorothioates to reduce exonuclease degradation and improve DNA barcode stability. To ensure equal amplification of each sequence, we included universal forward and reverse primer regions on all barcodes. Each barcode was distinguished using a distinct 8nt sequence. An 8nt sequence can generate over 48 (65,536) distinct barcodes. We used 156 distinct 8nt sequences designed by to prevent sequence bleaching on the Illumina MiniSeqTM sequencing machine.

Nanoparticle Characterization

LNP hydrodynamic diameter was measured using dynamic light scattering (DLS) (DynaPro Plate Reader II, Wyatt). LNPs were diluted in sterile 1X PBS to a concentration of ~0.06 μg/mL, and analyzed. LNPs were included if they met 3 criteria: diameter >20 nm, diameter <200 nm, and autocorrelation function with only 1 inflection point. Particles that met these criteria were pooled and dialyzed in 1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Invitrogen), and sterile filtered with a 0.22 μm filter.

Animal Experiments

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Female C57BL/6J (#000664), LDLR−/− (#002207), VLDLR−/− (#002529), and SpCas9 constitutive mice (#026179) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. All mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. In all experiments, mice were aged 5–8 weeks, and N = 3 or 4 mice per group were injected intravenously via the lateral tail vein (Supplementary Table 3). The nanoparticle concentration was determined using NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific).

Cell Isolation & Staining

Mice were perfused with 20 mL of 1X PBS through the right atrium. The lungs, spleen, and liver were isolated immediately following perfusion. Tissues were finely cut, and then placed in a digestive enzyme solution with Collagenase Type I (Sigma Aldrich), Collagenase XI (Sigma Aldrich), and Hyaluronidase (Sigma Aldrich) at 37ºC and 550 rpm for 45 minutes. The digestive enzyme for heart and spleen included Collagenase IV (Sigma Aldrich).6,34,35 Digested tissues were passed through a 70 μm filter and red blood cells were lysed. Cells were stained to identify specific cell populations and sorted using the BD FacsFusion cell sorter in the Georgia Institute of Technology Cellular Analysis Core. Antibody clones used for staining were: anti-CD31 (390, BioLegend), anti-CD45.2 (104, BioLegend), anti-CD11b (M1/70, BioLegend), and anti-CD102 (3C4, BioLegend).

Endothelial RNAi

C57BL/6J Mice were injected with 1.5 mg/kg siLuciferase or 1.5 mg/kg siICAM2 (AxoLabs). siRNAs were chemically modified at the 2’ position to increase stability and specificity, and negate immunostimulation. Both siGFP and siICAM2 sequences have been previously reported several times.6,34,35 Seventy-two hours after injection, tissues were isolated and protein expression was quantified as mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) using flow cytometry. ICAM2 MFI in PBS-treated mice was normalized to 100 percent, and all treated groups were compared to this control group.

Endothelial Gene Editing

Constitutive SpCas9 mice were injected with LNP-unmod or LNP-oleate delivering e-sgGFP (AxoLabs) at a dose of 1.0mg/kg. 5 days after injection, tissues were isolated, and cell types were sorted using FACs. DNA was extracted using QuickExtract and sanger sequencing was conducted by Eton Biosciences. Indel formation was measured by TIDE (https://tide-calculator.nki.nl).

PCR Amplification

All samples were amplified and prepared for sequencing using a two-step, nested PCR protocol. More specifically, 1 μL of each primer (10 uM Reverse/Forward) were added to 5 μL of Kapa HiFi 2X master mix, 2 μL sterile H2O, and 1 μL DNA template. This first PCR reaction was run for 30 cycles. The second PCR, to add Nextera XT chemistry, indices, and i5/i7 adapter regions was run for 5–10 cycles and used the product from ‘PCR 1’ as template If this initial PCR reaction did not produce clear bands, the primer concentrations, DNA template input, PCR temperature, and number of cycles were optimized for individual samples. The PCR amplicon was isolated using BluePippin (Sage Science).

Deep Sequencing

Illumina deep sequencing was conducted in Georgia Tech’s Molecular Evolution core. Runs were performed on an Illumina MiniseqTM. Primers were designed based on Nextera XT adapter sequences.

Data Normalization

Counts for each particle, per tissue, were normalized to the barcoded LNP mixture injected into mice, as previously described.4 This ‘input’ DNA was used to normalize DNA counts from the cells and tissues.

Data Analysis

Sequencing results were processed using a custom python-based tool to extract raw barcode counts for each tissue. These raw counts were then normalized with an R script prior to further analysis. Statistical analyses were done using GraphPad Prism 7. Correlation analyses were run assuming a Gaussian distribution in order to obtain Pearson correlation coefficients. R2 values (0 – 1) were computed by squaring Pearson correlation coefficients. Data is plotted as mean ± standard error mean unless otherwise stated.

Data Access

The data, analyses, and scripts used to generate all figures in the paper are available upon request to J.E.D. or dahlmanlab.org.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jordan Cattie and Taylor E. Shaw. The authors thank Sommer Durham and the Georgia Tech Cellular Analysis and Cytometry Core.

Funding. K.P., C.D.S., and J.E.D. were funded by Georgia Tech startup funds (awarded to J.E.D.). K.P. was also funded by the NIH/NIGMS-sponsored Cell and Tissue Engineering (CTEng) Biotechnology Training Program (T32GM008433). C.D.S. was also funded by the NIH/NIGMS-sponsored Immunoengineering Training Program (T32EB021962). M.G.C. was supported by the National Institutes of Health GT BioMAT Training Grant under Award Number 5T32EB006343 and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE-1451512. C.J.G. was funded by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under grant grant DGE-1650044. Research was funded by the Cystic Fibrosis Research Foundation (DAHLMA15XX0, awarded to J.E.D.), the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation (PDF-JFA-1860, awarded to J.E.D.), and the Bayer Hemophilia Awards Program (AGE DTD, awarded to J.E.D.). This work was performed in part at the Georgia Tech Institute for Electronics and Nanotechnology, a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure, which is supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant ECCS-1542174).

Footnotes

Author Contributions. K.P. and J.E.D. designed experiments. K.P., C.J.G., M.G.C., C.D.S., M.P.L., M.S., G.L., and A.V.B. performed the experiments. K.P. and J.E.D. analyzed the data. K.P. and J.E.D. wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Supporting Information Available. LNP library design, LNP inclusion criteria, FACS gating strategies for lung, spleen, and liver endothelial cells, macrophages, and hepatocytes, data normalization strategy, LNPs meeting inclusion criteria subdivided by cholesterol type, LNP diameter plotted against normalized delivery; schematic depicting enrichment procedure, enrichment of each cholesterol in each animal model, composition and formulation of the top 15% of LNPs in each cell type in each mouse model; normalized delivery in VLDLR−/− and LDLR−/− mice versus normalized delivery in WT mice for each cell type; size distribution for LNP-unmod and LNP-oleate with different payloads, sgRNA and siRNA sequences and modifications, normalized mouse weight for each day of each experiment; table depicting how 2,000 data points were obtained; significance data for Figure 2D, detailed description regarding mice used in each experiment.

Associated Content. Supporting information is available online. J.E.D. and K.P. have filed intellectual property related to this publication.

References

- 1.Blanco E, Shen H, Ferrari M. Principles of Nanoparticle Design for Overcoming Biological Barriers to Drug Delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:941–951. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng CJ, Tietjen GT, Saucier-Sawyer JK, Saltzman WM. A Holistic Approach to Targeting Disease with Polymeric Nanoparticles. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2015;14:239–247. doi: 10.1038/nrd4503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paunovska K, Sago CD, Monaco CM, Hudson WH, Castro MG, Rudoltz TG, Kalathoor S, Vanover DA, Santangelo PJ, Ahmed R, Bryksin AV, Dahlman JE. A Direct Comparison of in Vitro and in Vivo Nucleic Acid Delivery Mediated by Hundreds of Nanoparticles Reveals a Weak Correlation. Nano Lett. 2018;18:2148–2157. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b00432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahlman JE, Kauffman KJ, Xing Y, Shaw TE, Mir FF, Dlott CC, Langer R, Anderson DG, Wang ET. Barcoded Nanoparticles for High Throughput in Vivo Discovery of Targeted Therapeutics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:2060–2065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620874114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yaari Z, da Silva D, Zinger A, Goldman E, Kajal A, Tshuva R, Barak E, Dahan N, Hershkovitz D, Goldfeder M, Roitman JS, Schroeder A. Theranostic Barcoded Nanoparticles for Personalized Cancer Medicine. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13325. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahlman JE, Barnes C, Khan OF, Thiriot A, Jhunjunwala S, Shaw TE, Xing Y, Sager HB, Sahay G, Speciner L, Bader A, Bogorad RL, Yin H, Racie T, Dong Y, Jiang S, Seedorf D, Dave A, Singh Sandhu K, Webber MJ, et al. In Vivo Endothelial Sirna Delivery Using Polymeric Nanoparticles with Low Molecular Weight. Nat Nanotechnol. 2014;9:648–655. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Love KT, Mahon KP, Levins CG, Whitehead KA, Querbes W, Dorkin JR, Qin J, Cantley W, Qin LL, Racie T, Frank-Kamenetsky M, Yip KN, Alvarez R, Sah DW, de Fougerolles A, Fitzgerald K, Koteliansky V, Akinc A, Langer R, Anderson DG. Lipid-Like Materials for Low-Dose, in Vivo Gene Silencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1864–1869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910603106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akinc A, Zumbuehl A, Goldberg M, Leshchiner ES, Busini V, Hossain N, Bacallado SA, Nguyen DN, Fuller J, Alvarez R, Borodovsky A, Borland T, Constien R, de Fougerolles A, Dorkin JR, Narayanannair Jayaprakash K, Jayaraman M, John M, Koteliansky V, Manoharan M, et al. A Combinatorial Library of Lipid-Like Materials for Delivery of Rnai Therapeutics. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:561–569. doi: 10.1038/nbt1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Semple SC, Akinc A, Chen J, Sandhu AP, Mui BL, Cho CK, Sah DW, Stebbing D, Crosley EJ, Yaworski E, Hafez IM, Dorkin JR, Qin J, Lam K, Rajeev KG, Wong KF, Jeffs LB, Nechev L, Eisenhardt ML, Jayaraman M, et al. Rational Design of Cationic Lipids for Sirna Delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:172–176. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou K, Nguyen LH, Miller JB, Yan Y, Kos P, Xiong H, Li L, Hao J, Minnig JT, Zhu H, Siegwart DJ. Modular Degradable Dendrimers Enable Small Rnas to Extend Survival in an Aggressive Liver Cancer Model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:520–525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1520756113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong Y, Love KT, Dorkin JR, Sirirungruang S, Zhang Y, Chen D, Bogorad RL, Yin H, Chen Y, Vegas AJ, Alabi CA, Sahay G, Olejnik KT, Wang W, Schroeder A, Lytton-Jean AK, Siegwart DJ, Akinc A, Barnes C, Barros SA, et al. Lipopeptide Nanoparticles for Potent and Selective Sirna Delivery in Rodents and Nonhuman Primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:3955–3960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322937111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mui BL, Tam YK, Jayaraman M, Ansell SM, Du X, Tam YY, Lin PJ, Chen S, Narayanannair JK, Rajeev KG, Manoharan M, Akinc A, Maier MA, Cullis P, Madden TD, Hope MJ. Influence of Polyethylene Glycol Lipid Desorption Rates on Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Sirna Lipid Nanoparticles. Mol Ther —Nucleic Acids. 2013;2:e139. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2013.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshida H, Kisugi R. Mechanisms of Ldl Oxidation. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:1875–1882. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikonen E. Cellular Cholesterol Trafficking and Compartmentalization. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:125–138. doi: 10.1038/nrm2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cases S, Novak S, Zheng YW, Myers HM, Lear SR, Sande E, Welch CB, Lusis AJ, Spencer TA, Krause BR. Acat-2 a Second Mammalian Acyl-Coa: Cholesterol Acyltransferase Its Cloning Expression and Characterization. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26755–26764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cases S, Smith SJ, Zheng YW, Myers HM, Lear SR, Sande E, Novak S, Collins C, Welch CB, Lusis AJ. Identification of a Gene Encoding an Acyl Coa: Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase, a Key Enzyme in Triacylglycerol Synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13018–13023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wasan KM, Brocks DR, Lee SD, Sachs-Barrable K, Thornton SJ. Impact of Lipoproteins on the Biological Activity and Disposition of Hydrophobic Drugs: Implications for Drug Discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2008;7:84–99. doi: 10.1038/nrd2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinbrecher UP, Zhang H, Lougheed M. Role of Oxidatively Modified Ldl in Atherosclerosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;9:155–168. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hulthe J, Fagerberg B. Circulating Oxidized Ldl Is Associated with Subclinical Atherosclerosis Development and Inflammatory Cytokines (Air Study) Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1162–1167. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000021150.63480.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tall AR, Yvan-Charvet L. Cholesterol, Inflammation and Innate Immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:104–116. doi: 10.1038/nri3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller YI, Choi SH, Wiesner P, Fang L, Harkewicz R, Hartvigsen K, Boullier A, Gonen A, Diehl CJ, Que X. Oxidation-Specific Epitopes Are Danger-Associated Molecular Patterns Recognized by Pattern Recognition Receptors of Innate Immunity. Circ Res. 2011;108:235–248. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li D, Mehta J. Oxidized Ldl, a Critical Factor in Atherogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68:353–354. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manninen V, Tenkanen L, Koskinen P, Huttunen JK, Mänttäri M, Heinonen OP, Frick MH. Joint Effects of Serum Triglyceride and Ldl Cholesterol and Hdl Cholesterol Concentrations on Coronary Heart Disease Risk in the Helsinki Heart Study. Implications for Treatment. Circulation. 1992;85:37–45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armstrong V, Cremer P, Eberle E, Manke A, Schulze F, Wieland H, Kreuzer H, Seidel D. The Association between Serum Lp (a) Concentrations and Angiographically Assessed Coronary Atherosclerosis: Dependence on Serum Ldl Levels. Atherosclerosis. 1986;62:249–257. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(86)90099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kontush A, Chapman MJ. Antiatherogenic Small, Dense Hdl—Guardian Angel of the Arterial Wall? Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2006;3:144–153. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lorenzer C, Dirin M, Winkler AM, Baumann V, Winkler J. Going Beyond the Liver: Progress and Challenges of Targeted Delivery of Sirna Therapeutics. J Control Release. 2015;203:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holvoet P, Keyzer DD, Jacobs D., Jr Oxidized Ldl and the Metabolic Syndrome. Future Lipidol. 2008;3:637–649. doi: 10.2217/17460875.3.6.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The Metabolic Syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365:1415–1428. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coelho T, Adams D, Silva A, Lozeron P, Hawkins PN, Mant T, Perez J, Chiesa J, Warrington S, Tranter E, Munisamy M, Falzone R, Harrop J, Cehelsky J, Bettencourt BR, Geissler M, Butler JS, Sehgal A, Meyers RE, Chen Q, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Rnai Therapy for Transthyretin Amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:819–829. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishibashi S, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Gerard RD, Hammer RE, Herz J. Hypercholesterolemia in Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor Knockout Mice and Its Reversal by Adenovirus-Mediated Gene Delivery. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:883–893. doi: 10.1172/JCI116663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frykman PK, Brown MS, Yamamoto T, Goldstein JL, Herz J. Normal Plasma Lipoproteins and Fertility in Gene-Targeted Mice Homozygous for a Disruption in the Gene Encoding Very Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:8453–8457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akinc A, Querbes W, De S, Qin J, Frank-Kamenetsky M, Jayaprakash KN, Jayaraman M, Rajeev KG, Cantley WL, Dorkin JR, Butler JS, Qin L, Racie T, Sprague A, Fava E, Zeigerer A, Hope MJ, Zerial M, Sah DW, Fitzgerald K, et al. Targeted Delivery of Rnai Therapeutics with Endogenous and Exogenous Ligand-Based Mechanisms. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1357–1364. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bertrand N, Grenier P, Mahmoudi M, Lima EM, Appel EA, Dormont F, Lim JM, Karnik R, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Mechanistic Understanding of in Vivo Protein Corona Formation on Polymeric Nanoparticles and Impact on Pharmacokinetics. Nat Commun. 2017;8:777. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00600-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sager HB, Dutta P, Dahlman JE, Hulsmans M, Courties G, Sun Y, Heidt T, Vinegoni C, Borodovsky A, Fitzgerald K, Wojtkiewicz GR, Iwamoto Y, Tricot B, Khan OF, Kauffman KJ, Xing Y, Shaw TE, Libby P, Langer R, Weissleder R, et al. Rnai Targeting Multiple Cell Adhesion Molecules Reduces Immune Cell Recruitment and Vascular Inflammation after Myocardial Infarction. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:342ra380–342ra380. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sager HB, Hulsmans M, Lavine KJ, Moreira MB, Heidt T, Courties G, Sun Y, Iwamoto Y, Tricot B, Khan OF, Dahlman JE, Borodovsky A, Fitzgerald K, Anderson DG, Weissleder R, Libby P, Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M. Proliferation and Recruitment Contribute to Myocardial Macrophage Expansion in Chronic Heart Failure. Circ Res. 2016;119:853–864. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White K, Lu Y, Annis S, Hale AE, Chau BN, Dahlman JE, Hemann C, Opotowsky AR, Vargas SO, Rosas I, Perrella MA, Osorio JC, Haley KJ, Graham BB, Kumar R, Saggar R, Saggar R, Wallace WD, Ross DJ, Khan OF, et al. Genetic and Hypoxic Alterations of the Microrna-210-Iscu1/2 Axis Promote Iron-Sulfur Deficiency and Pulmonary Hypertension. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7:695–713. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201404511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore KJ, Sheedy FJ, Fisher EA. Macrophages in Atherosclerosis: A Dynamic Balance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:709–721. doi: 10.1038/nri3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choudhury RP, Lee JM, Greaves DR. Mechanisms of Disease: Macrophage-Derived Foam Cells Emerging as Therapeutic Targets in Atherosclerosis. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2005;2:309–315. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore KJ, Tabas I. Macrophages in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. Cell. 2011;145:341–355. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. The Srebp Pathway: Regulation of Cholesterol Metabolism by Proteolysis of a Membrane-Bound Transcription Factor. Cell. 1997;89:331–340. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chawla A, Saez E, Evans RM. Don't Know Much Bile-Ology. Cell. 2000;103:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hassan HH, Denis M, Krimbou L, Marcil M, Genest J. Cellular Cholesterol Homeostasis in Vascular Endothelial Cells. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:35B–40B. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70985-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Connell BJ, Denis M, Genest J. Cellular Physiology of Cholesterol Efflux in Vascular Endothelial Cells. Circulation. 2004;110:2881–2888. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000146333.20727.2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ronan T, Qi Z, Naegle KM. Avoiding Common Pitfalls When Clustering Biological Data. Sci Signaling. 2016;9:re6–re6. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aad1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan OF, Zaia EW, Yin H, Bogorad RL, Pelet JM, Webber MJ, Zhuang I, Dahlman JE, Langer R, Anderson DG. Ionizable Amphiphilic Dendrimer-Based Nanomaterials with Alkyl-Chain-Substituted Amines for Tunable Sirna Delivery to the Liver Endotheliumin Vivo. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53:14397–14401. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yin H, Song C-Q, Suresh S, Wu Q, Walsh S, Rhym LH, Mintzer E, Bolukbasi MF, Zhu LJ, Kauffman K, Mou H, Oberholzer A, Ding J, Kwan S-Y, Bogorad RL, Zatsepin T, Koteliansky V, Wolfe SA, Xue W, Langer R, et al. Structure-Guided Chemical Modification of Guide Rna Enables Potent Non-Viral in Vivo Genome Editing. Nat Biotechnol. 2017:1179–1187. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brinkman EK, Chen T, Amendola M, van Steensel B. Easy Quantitative Assessment of Genome Editing by Sequence Trace Decomposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e168. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Finn JD, Smith AR, Patel MC, Shaw L, Youniss MR, van Heteren J, Dirstine T, Ciullo C, Lescarbeau R, Seitzer J, Shah RR, Shah A, Ling D, Growe J, Pink M, Rohde E, Wood KM, Salomon WE, Harrington WF, Dombrowski C, et al. A Single Administration of Crispr/Cas9 Lipid Nanoparticles Achieves Robust and Persistent in Vivo Genome Editing. Cell Rep. 2018;22:2227–2235. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller JB, Zhang S, Kos P, Xiong H, Zhou K, Perelman SS, Zhu H, Siegwart DJ. Non-Viral Crispr/Cas Gene Editing in Vitro and in Vivo Enabled by Synthetic Nanoparticle Co-Delivery of Cas9 Mrna and Sgrna. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2017;56:1059–1063. doi: 10.1002/anie.201610209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang C, Mei M, Li B, Zhu X, Zu W, Tian Y, Wang Q, Guo Y, Dong Y, Tan X. A Non-Viral Crispr/Cas9 Delivery System for Therapeutically Targeting Hbv DNA and Pcsk9 in Vivo. Cell Res. 2017;27:440–443. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hsu PD, Lander ES, Zhang F. Development and Applications of Crispr-Cas9 for Genome Engineering. Cell. 2014;157:1262–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Doudna JA, Charpentier E. Genome Editing. The New Frontier of Genome Engineering with Crispr-Cas9. Science. 2014;346:1258096. doi: 10.1126/science.1258096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ulitsky I, Bartel DP. Lincrnas: Genomics, Evolution, and Mechanisms. Cell. 2013;154:26–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bartel DP. Micrornas: Target Recognition and Regulatory Functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poisson J, Lemoinne S, Boulanger C, Durand F, Moreau R, Valla D, Rautou PE. Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells: Physiology and Role in Liver Diseases. J Hepatol. 2017;66:212–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuai R, Li D, Chen YE, Moon JJ, Schwendeman A. High-Density Lipoproteins (Hdl) – Nature’s Multi-Functional Nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2016;10:3015–3041. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Monopoli MP, Aberg C, Salvati A, Dawson KA. Biomolecular Coronas Provide the Biological Identity of Nanosized Materials. Nat Nanotechnol. 2012;7:779–786. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen D, Love KT, Chen Y, Eltoukhy AA, Kastrup C, Sahay G, Jeon A, Dong Y, Whitehead KA, Anderson DG. Rapid Discovery of Potent Sirna-Containing Lipid Nanoparticles Enabled by Controlled Microfluidic Formulation. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:6948–6951. doi: 10.1021/ja301621z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yun S, Budatha M, Dahlman JE, Coon BG, Cameron RT, Langer R, Anderson DG, Baillie G, Schwartz MA. Interaction between Integrin Alpha5 and Pde4d Regulates Endothelial Inflammatory Signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2016:1043–1053. doi: 10.1038/ncb3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Platt RJ, Chen S, Zhou Y, Yim MJ, Swiech L, Kempton HR, Dahlman JE, Parnas O, Eisenhaure TM, Jovanovic M, Graham DB, Jhunjhunwala S, Heidenreich M, Xavier RJ, Langer R, Anderson DG, Hacohen N, Regev A, Feng G, Sharp PA, et al. Crispr-Cas9 Knockin Mice for Genome Editing and Cancer Modeling. Cell. 2014;159:440–455. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xue W, Dahlman JE, Tammela T, Khan OF, Sood S, Dave A, Cai W, Chirino LM, Yang GR, Bronson R, Crowley DG, Sahay G, Schroeder A, Langer R, Anderson DG, Jacks T. Small Rna Combination Therapy for Lung Cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E3553–E3561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412686111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koga J, Nakano T, Dahlman JE, Figueiredo JL, Zhang H, Decano J, Khan OF, Niida T, Iwata H, Aster JC, Yagita H, Anderson DG, Ozaki CK, Aikawa M. Macrophage Notch Ligand Delta-Like 4 Promotes Vein Graft Lesion Development: Implications for the Treatment of Vein Graft Failure. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:2343–2353. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.