Abstract

Background

The patient’s perspective of their facial scar after skin cancer surgery influences perception of care and quality of life. Appearance satisfaction after surgery is also an important but often overlooked treatment outcome.

Objectives

To report the psychometric validation of the FACE-Q Skin Cancer Module consisting of 5 scales measuring appearance satisfaction (Satisfaction with Facial Appearance, Appraisal of Scars), quality of life (Cancer Worry, Appearance-related Psychosocial Distress) and the patient experience (Satisfaction with Information: Appearance).

Methods

Participants underwent Mohs surgery for facial basal or squamous cell carcinoma or excision of early facial melanoma. Cohort 1 received a set of scales before and after surgery. Cohort 2 received the scales on 2 occasions in the postoperative period for test-retest reliability. Rasch measurement theory was used to select (item-reduce) the most clinically meaningful items for the scales. Reliability, validity, floor and ceiling effects and responsiveness were also analysed.

Results

Of 334 patients, 209 (response rate 62.6%) were included. Rasch analysis reduced the total scale items from 77 to 41. All items had ordered thresholds and good psychometric fit. Reliability was high (Person separation index and Cronbach α ≥0.90) and scales measuring similar constructs correlated. High floor and ceiling effects were seen for the scales. The Cancer Worry scale demonstrated responsiveness (p=0.004).

Conclusions

The FACE-Q Skin Cancer Module meet the requirements of the Rasch model providing linearized measurement. Discriminating between patients with minimal appearance or worry impairment may be a limitation. The scales can be used for larger validation studies, clinical practice and research.

INTRODUCTION

As the incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) and melanoma has risen globally over the last few decades, (1, 2) surgical management of facial skin malignancies has also increased.(3) Studies have shown that skin tumours located on the face and facial scarring are associated with significant psychologic morbidity.(4, 5) As physical appearance directly influences emotions and social interactions, scarring from facial surgery can impact an individual’s self-perception. The patient’s perspective of their aesthetic outcome is becoming increasingly important. However, as appearance is subjective, patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments are questionnaires designed to quantify the patient’s perspective of their disease and/or treatment.

The patient’s assessment of their aesthetic outcome after surgery can differ from the surgeon’s perspective.(6, 7) Furthermore, this perception markedly influences the patient’s satisfaction with the overall care provided.(8) Patients may be dissatisfied if their scar size is greater than anticipated or others will struggle to adapt to appearance changes leading to anxiety, social isolation and a decreased quality of life (QOL). (9, 10) Although patients express concerns related to scar appearance, it is minimally addressed with validated measures.(11) In a systematic review performed by the authors of PRO instruments used in nonmelanoma skin cancer, only the Skin Cancer Index (SCI) addressed appearance with limited questions about attractiveness and scar size/noticeability.(12) Attributes related to overall appearance and scarring may contribute to dissatisfaction and psychosocial distress yet are not addressed by existing PRO instruments, suggesting a more comprehensive instrument is needed.

The vast majority of existing PRO instruments were developed and validated with the traditional classic test theory approach, however newer or modern psychometric approaches (e.g. Rasch Measurement Theory) improve the clinical interpretation of the scale scores.(13) In this approach, the qualitative phase is crucial as it provides data that can be used to create the content for a set of independently functioning scales, each of which function like a “ruler” whereby the items map out a clinical hierarchy to reflect less of the concept (e.g., cancer worry) at one end of the scale to more of the concept at the other end. The field-test data is then analysed to see if the scale’s clinical hierarchy worked as hypothesized. When data collected for a scale meet the requirements of the Rasch model the scale can be said to provide linearized measurement.

The FACE-Q (14-19) is a multi-module PRO instrument developed for the aesthetic patient undergoing elective surgical and nonsurgical procedures. The FACE-Q Skin Cancer Module was developed for patients undergoing surgical procedures for facial skin cancers as additional concerns were identified by our group such as cancer worry and appearance (i.e. scarring), similar to previous research in this area.(11, 20, 21) The module consists of 5 scales that address constructs identified to be important to facial skin cancer patients.(20) In this study, the FACE-Q Skin Cancer Module scales are psychometrically analysed and validated with a modern psychometric approach for clinical use in the skin cancer population.

METHODS

Ethics review board approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). The FACE-Q Skin Cancer was developed according to the US Food and Drug Administration guidance to industry and other recommended guidelines for the development of a PRO instrument.(22-25) To develop the conceptual framework and scales, a pool of items was generated from 3 sources: a systematic review of the literature,(12) qualitative interviews and expert opinion. In-depth qualitative interviews were conducted from 15 participants with NMSC and early melanoma to generate the themes most important to patients. The themes included appearance-related concerns, psychological and social function, adverse problems and the experience of care.(20) Participants were also shown the FACE-Q Satisfaction with Facial Appearance and Psychological Distress scales (14, 26) to identify items that might be relevant to skin cancer patients. Examples of response options for possible inclusion were also reviewed for feedback.

The Face-Q Skin Cancer Module consists of 2 scales related to appearance, 2 quality of life scales and 1 patient experience scale (Table 1). All the scales were developed with four response options in keeping with the best practice for scale development.(27) The scales are available in the Appendix (S1). The scales were pilot-tested with 5 participants to clarify ambiguities, confirm acceptability and completion time. To determine the final number of items in each of the scales and checklists, a field-test study was performed.

Table 1.

FACE-Q Skin Cancer Scales including Number of Items and Type of Response Option

| Name of Scale | Items | Example Item | Response Option Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facial Appearance | 9 | How symmetric your face looks? | Dissatisfied/satisfied |

| Appraisal of Scars | 8 | The color of your scar? | Extremely bothered/not at all |

| Cancer Worry | 10 | I worry my skin cancer may come back after treatment. | Agree/disagree |

| Appearance-related Psychosocial Distress | 8 | I feel self-conscious about how my face looks. | Agree/disagree |

| Information: Appearance | 6 | What your scar(s) would look like? | Dissatisfied/satisfied |

Data collection for field-testing (Phase 2)

We enrolled patients 18 years or older undergoing Mohs surgery for a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the head and neck region or excision for an early (stage 0 or 1A) melanoma. Participant information such as age, sex, skin cancer site, diagnosis and type of surgical repair was obtained from the medical records. Recruitment was from July 2014 to July 2015. There were two patient cohorts:

Cohort 1 was approached by the research team in clinic and if enrolled, they received the Cancer Worry and Appearance-related Distress scales before surgery. After surgery, the same group received the same scales and in addition, received the Satisfaction with Facial Appearance, Appraisal of Scars, and Satisfaction with Information: Appearance scales.

Cohort 2 completed dermatologic surgery at MSKCC within 3 years. In the Mohs and Dermatologic Surgery Unit, procedure notes from surgical cases are prospectively stored. Participants for possible inclusion were selected from this database. To reflect clinical practice, a wide range of ages and surgical repair types were included. Participants unable to speak or read English and locations not on facial skin were excluded. This group was mailed the same set of scales (Cancer Worry, Appearance-related Psychosocial Distress, Satisfaction with Facial Appearance, Appraisal of Scars, Satisfaction with Information: Appearance) with instructions to complete one set upon receipt of the package and the second 2 weeks later. The participants were asked to answer the questions in reference to their most recent skin cancer treatment. To increase participation, a gift card incentive was included. The participants also received a reminder letter and telephone call.

The scales are scored separately. For each scale, if missing data was less than 50% of the scale’s items, the responses were summed. Using a conversion table specific to each scale, the Rasch logit scores were transformed into 0 to 100. Higher scores for the 2 appearance scales and the information scale indicated a better outcome; whereas higher scores for cancer worry and psychosocial distress scales indicated worse outcomes.

STASTICAL ANALYSIS

Rasch measurement theory (RMT) analysis (28, 29) was used to select the items for the final versions of the scales with RUMM2030 statistical software.(30) The analysis uses a number of statistical and graphic tests to examine each item in a scale (31-33) and considers the results together when making decisions about the overall scale quality. For the 5 scales we performed:

Threshold for item response options: For each scale, we examined thresholds between response options (e.g. very dissatisfied and somewhat dissatisfied) to determine if a scale’s response categories scored with successive integer scores as intended.

-

Item fit statistics: The items of a scale must work together (fit) as a set both clinically and statistically. When items do not fit (misfit), it is inappropriate to sum item responses to reach a total score and the validity of the scale is questioned. As there are no absolute criteria for interpreting fit statistics, it is more meaningful to interpret them together and in the context of their clinical usefulness.

Three indicators of fit were assessed: (1) log residuals (item-person interaction), (2) Chi-square (x2) values (item-trait interaction) and (3) item characteristic curves. Fit residual should fall between -2.5 and +2.5 with associated nonsignificant chi-square values after Bonferroni adjustment.(31)

Dependency: Residual correlations between pairs of items were examined to identify any that were 0.30 or higher as high residual correlations can artificially inflate reliability.

Targeting: informs about the suitability of the sample for evaluating the scales and how suitable the scale is for measuring the sample. Better targeting allows for an improved ability to interpret the psychometric data with confidence. We examined person and item locations to determine if items were evenly spread across a reasonable range that matched the range of the construct experienced by the sample.

Person separation index (PSI): We examined internal reliability using the PSI, a statistic comparable to the Cronbach α. The PSI measures error associated with the measurement of people in a sample. Higher values indicate greater reliability.

Cronbach α was computed for each scale, which provides a measure of how closely related a set of items are as a group (internal consistency).(34) For test-retest reliability, interclass correlations (ICC) was computed.(35) Floor and ceiling effects for each scale were also calculated.

For responsiveness, we computed group-level change for the 2 scales (Cancer Worry and Appearance-related Psychosocial Distress) completed by a subgroup before and after surgery. Cancer worry was anticipated to decrease after surgery whereas, appearance-related distress was expected to remain the same or increase after surgery. We compared preoperative and postoperative Rasch transformed scores using paired t-test and then calculated an effect size (34) (i.e., the mean time 1 (preop) minus the mean time 2 (postop) divided by the standard deviation at time 1). Cohen criteria were used to interpret the results (0.2 is small, 0.5 is moderate and 0.8 is large).(36-39)

Construct validity

Pearson correlations were performed to exam associations among scores and 2-tailed independent sample t tests to assess for differences among means to test the hypotheses:

Scales measuring similar constructs (e.g. appearance) would correlate more with each other.

Higher cancer worry scores (more worry) would correlate with higher appearance-related psychosocial distress (more distress). Degree of cancer worry may also correlate with appearance scores with more worry being associated with lower facial satisfaction and more scar bother.

RESULTS

Response Rate and Sample Characteristics

A total of 334 participants were approached of which 89 participants were enrolled in cohort 1 and 120 participants enrolled in cohort 2 (already had surgery) for an overall response rate of 62.6%. In cohort 1, the participants completed the postoperative scales at a median of 16 days after surgery. In cohort 2, 52 participants filled out the scales a second time for the test-retest (43.3%) at an average of 26 days (median 17 days, range 12-105 days). There was one outlier of 105 days and without this outlier, the maximum number of days was 62. Patient characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics of sample (n=209)

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age (y) | |

| Mean [range] | 64 [25-92] |

|

| |

| Sex | |

| Female | 113 (54.1) |

| Male | 96 (45.9) |

|

| |

| Skin cancer | |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 143 (68.4) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 40 (19.1) |

| Melanoma | 25 (12.0) |

| Other | 1 (0.5) |

|

| |

| Repair | |

| Second intention | 31 (14.8) |

| Primary repair | 101 (48.3) |

| Flap repair | 54 (25.8) |

| Skin graft | 20 (9.6) |

| Other (nonsurgical) | 3 (1.4) |

|

| |

| Scales completed (n=326)* | |

| Cancer worry | 321 (98.5) |

| Facial appearance | 229 (70.2) |

| Scar appearance | 234 (71.8) |

| Appearance Distress | 326 (100.0) |

| Information | 232 (71.2) |

Includes participants who completed the scales/checklists more than once

Rasch Measurement Theory (RMT) Analysis

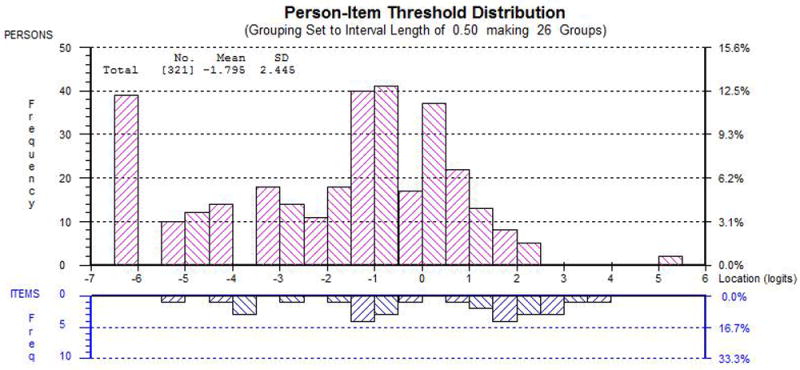

The RMT analysis supported the reliability and validity of the 5 independent scales. The Satisfaction with Facial Appearance scale was reduced from 14 to 9 items, Appraisal of Scars from 13 to 8 items, Cancer Worry from 15 to 10 items, Appearance-related Psychosocial Distress from 15 to 8 items and Satisfaction with Information: Appearance from 20 to 6 items. All 41 items had ordered thresholds, which provide evidence that the response options for each scale worked as a continuum that increased for the construct being measured. Only 1 item was minimally outside the -2.5 to +2.5 range (Appendix Table S3). This item (Information scale: options scar) was retained, given that the other fit statistics were satisfied. The chi-square p values for all 41 items were nonsignificant, also indicating good item fit. For dependency, the item residuals were above 0.30 for four pairs of items; however, subtests performed revealed only a marginal effect on the scale reliability (0 to 0.01 differences in PSI value). In Figure 1, this histogram shows how well the participants are measured by the items of the Cancer Worry scale. The top histogram shows the frequency of person estimates (or measurements) and the bottom histogram shows the frequency of item thresholds (for each response option for each item). Less cancer worry is represented towards the left of the histograms, more to the right. For 88% of sample there is good coverage of item thresholds, meaning there are items to verbalize the different levels of cancer worry for each of these participants. Conversely, 12% of the sample scored at the floor of the scale and, therefore, are not covered by the scale content.

Figure 1.

Person-Item Threshold Distribution for Cancer Worry. The x-axis represents cancer worry. The y-axis shows the frequency of person locations (top histogram) and item locations (bottom histogram).

The 5 scales demonstrate high reliability. The PSI ranged from 0.81 to 0.90 with extremes included and excluded indicating good internal reliability (Table 3). Cronbach α values were 0.90 and higher. The ICC value was 0.93 and higher for the appearance, scar, psychosocial distress and information scale and 0.76 for cancer worry. The Appearance-related Psychosocial Distress scale show a floor effect of 40% and for the Cancer Worry scale, 15%. The ceiling effects were > 30% for the two appearance scales and the Satisfaction with Information scale (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Reliability Statistics and Floor and Ceiling Effects

| Scale | PSI with extremes | PSI with no extremes | Cronbach α | ICC | % floor Score 0 | % ceiling Score 100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 1.7 | 32.8 |

| Scar | 0.81 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.4 | 40.6 |

| Worry | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.76 | 15.3 | 0.6 |

| Distress | 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 39.9 | 0 |

| Information | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 1.3 | 47.6 |

PSI = Person Separation Index

ICC = Interclass correlation coefficients

The endorsement frequencies and missing values for the 5 Scales are provided in the Appendix (S2). The endorsement frequencies show the clinical hierarchy for each scale. For example, for the Satisfaction with Facial Appearance scale, the clinical hierarchy ranges from the item “The shape of your face” which had 64% of participants indicate they were very satisfied to “How your face looks up close”, which had 40% of participants indicate they were very satisfied. Between the two ends of the “ruler,” the remaining 8 items mapped out the scales’ concept in terms of decreasing satisfaction with appearance of the face.

Responsiveness

Sixty-three participants completed the Cancer Worry and Appearance-related Psychosocial Distress scales before and after surgery. Cancer Worry scores changed from a mean of 40.2 (SD 17.6) before surgery to 32.2 (SD 20.8) after surgery (p=0.004, effect size 0.46) which shows a significant improvement after surgery and a moderate effect size. The psychosocial distress scale scores did not have a significant change before (mean score 18.6 (SD 16.1) and after (19.9 (SD 20.3) surgery (p=0.61, effect size -0.1).

Construct validity

Pearson correlations between the appearance (facial appearance and scar [0.55, p=0.01]) and QOL scales (cancer worry and appearance-related psychosocial distress [0.39, p=0.01]) correlated and were significant. Higher cancer worry scores correlated with more appearance-related psychosocial distress (0.39, p=0.01) and less satisfaction with facial appearance (-0.18, p=0.01) and more scar bother after surgery (-0.27, p=0.01).

DISCUSSION

Facial appearance defines an individual’s identity, and directly influences emotions and social interactions. (40) Therefore, visible scarring can lead to anxiety, poor self-esteem and a decreased quality of life. (41) While satisfaction with facial appearance after surgery is an important outcome, it is often overlooked in dermatologic surgery. The FACE-Q Skin Cancer Module provides the dermatologic and reconstructive surgery communities with a comprehensive set of meaningful and scientifically sound set of scales for the facial skin cancer population.

The psychometric analyses provide evidence of reliability and validity of the 5 scales that comprise the FACE-Q Skin Cancer Module. The use of RMT methods has fundamental advantages. The RMT methods differ from traditional psychometric methods (based on classic test theory) because their focus is on the association between a persons’ measurement and the probability of responding to an item, rather than the association between a person’s measurement and the observed scale total score.(31) Advantages of using RMT to develop PRO instruments include: (1) RMT provides measurements of people that are independent of the sampling distribution of the people in whom they are developed, (2) RMT improves the potential to diagnose item-level psychometric issues and (3) RMT allows for a more accurate picture of individual person measurements.(31) These qualities, together with the qualitative work performed to create the FACE-Q Skin Cancer Module are what set it apart from other PRO instruments in the same clinical area. A recent Dutch questionnaire also utilized modern psychometrics (item response theory); however, the appearance questions are limited to scar worry and attractiveness and not specific to scar attributes or overall facial appearance.(42)

The 2 appearance scales ask about satisfaction with facial appearance and the degree of bother for different scar attributes, respectively. The majority of studies assessing QOL in the NMSC population use the Skindex-16 (12) a rigorously developed instrument that focuses on symptoms, emotions and physical/social limitations.(43) A PRO questionnaire specific to advanced BCC and BCC nevus syndrome showed that scarring was an important patient concern.(44) Studies have also demonstrated diminished QOL with scarring and the value of reconstruction of facial defects.(6, 40) Therefore, an instrument that measures facial appearance satisfaction and scar outcome is especially applicable to the skin cancer population.

The Satisfaction with Information: Appearance scale inquiries about scar and healing expectations. As the patients’ perception of their scars influences service perception,(8) this scale could be used to identify patient education gaps for an individual clinician and for larger quality improvement efforts. The correlation between scales also showed more worry and appearance-related distress were negatively correlated with appearance satisfaction suggesting a potential relationship between these constructs for future studies. The scales could explore the driving factors for patient satisfaction; for example, addressing specific scar attributes may impact overall facial satisfaction and in turn, appearance-related distress. An advantage of using Rasch analysis as the statistical model is that the scores are interpreted for the individual person and not for group comparisons only.(45) The scale scores are interpreted at the individual level to offer tangible and unique clinical benefits for the clinician.

We acknowledge there could be some bias as the sample is from one institution and participants were not recruited consecutively. However, the responses were varied and a range of patients participated. The number of questionnaires filled out for each scale varied reflecting the challenges of obtaining follow-up and mail surveys despite including a monetary incentive card. The presence of floor and ceiling effects in the current scales indicate an inability to differentiate between patients with low levels of impairment. It could be argued that this could be due to a limitation in the content validity of these scales. However, our previous research(46) and extensive qualitative research developing the current scales, suggests this is more likely a reflection of the clinical picture related to low morbidity. Thus, the floor effect for the cancer worry scale may reflect the perceived less serious nature of NMSC, for at least a proportion of patients. The observed greater ceiling effects (facial appearance, scar bother scales) and floor effect (appearance-related distress scale) may reflect minimal impact of surgical scarring and successful healing experienced by many patients. Never-the-less, it is important to bear in mind that our scales are better targeted to those patients with greater impairments related to NMSC.

The FACE-Q Skin Cancer Module is a promising new instrument that can be used by dermatologic and plastic surgeons to evaluate their outcomes at the individual patient or larger practice level. The unique inclusion of facial appearance and scar appraisal and quality of life allows for future studies comparing the long-term success of different surgical techniques from the patient’s perspective. It could also aid in identifying patients at risk for poor outcomes and dissatisfaction and allow for rigorous studies in different age groups and anatomic locations to further validate the instrument. The FACE-Q Skin Cancer Module can be used for clinical practice, research or quality improvement and may complement existing clinician-based outcomes.

Supplementary Material

What is already known about this topic?

Surgical treatment of facial skin cancers leads to scarring and changes in appearance that may negatively impact quality of life.

The aesthetic outcome of surgery is strongly correlated to patient satisfaction.

Current patient-reported outcome instruments are limited in their elicitation of appearance and scar satisfaction.

What does this study add?

The FACE-Q Skin Cancer Module scales measure facial and scar appearance, appearance-related psychosocial distress, cancer worry and the patient experience.

The FACE-Q Skin Cancer Module scales was validated with modern psychometric methods (i.e. Rasch measurement theory) for greater clinical applicability and individualization of scores.

What are the clinical implications of this work?

The FACE-Q Skin Cancer Module is recommended for clinical care to improve individual patient outcomes and to inform research studies.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: This research is supported by The Skin Cancer Foundation and in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Andrea Pusic, Anne Klassen and Stefan Cano are co-developers of the FACE-Q which is owned by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

References

- 1.Organization WH. http://www.who.int/uv/faq/skincancer/en/index1.html.

- 2.Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, Coldiron BM. Incidence Estimate of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer (Keratinocyte Carcinomas) in the U.S. Population, 2012. JAMA dermatology. 2015;151(10):1081–6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donaldson MR, Coldiron BM. Dermatologists perform the majority of cutaneous reconstructions in the Medicare population: numbers and trends from 2004 to 2009. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2013;68(5):803–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinbauer J, K M, Kohl E, Karrer S, et al. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges Quality of life in health care of non-melanoma skin cancer- results of a pilot study. Journal of Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:129–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2010.07547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dropkin MJ. Body image and quality of life after head and neck cancer surgery. Cancer Pract. 1999;7:309–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.76006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown BC, McKenna SP, Siddhi K, McGrouther DA, Bayat A. The hidden cost of skin scars: quality of life after skin scarring. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2008;61(9):1049–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young VL, Hutchison J. Insights into patient and clinician concerns about scar appearance: semiquantitative structured surveys. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2009;124(1):256–65. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a80747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon AJ, Dixon MP, Dixon JB. Prospective study of long-term patient perceptions of their skin cancer surgery. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2007;57(3):445–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassileth BR, Lusk EJ, Tenaglia AN. Patients’ perceptions of the cosmetic impact of melanoma resection. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1983;71(1):73–5. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198301000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dropkin MJ. Coping with disfigurement and dysfunction after head and neck cancer surgery: a conceptual framework. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1989;5(3):213–9. doi: 10.1016/0749-2081(89)90095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radiotis G, Roberts N, Czajkowska Z, Khanna M, Korner A. Nonmelanoma skin cancer: disease-specific quality-of-life concerns and distress. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(1):57–65. doi: 10.1188/14.ONF.57-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee EH, Klassen AF, Nehal KS, Cano SJ, Waters J, Pusic AL. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome instruments of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the dermatologic population. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2013;69(2):e59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cano SJ, Hobart JC. The problem with health measurement. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:279–90. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S14399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Cano SJ. Development and psychometric evaluation of the FACE-Q satisfaction with appearance scale: a new patient-reported outcome instrument for facial aesthetics patients. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2013;40(2):249–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Scott A, Snell L, Pusic AL. Measuring patient-reported outcomes in facial aesthetic patients: development of the FACE-Q. Facial plastic surgery : FPS. 2010;26(4):303–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panchapakesan V, Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Scott AM, Pusic AL. Development and psychometric evaluation of the FACE-Q Aging Appraisal Scale and Patient-Perceived Age Visual Analog Scale. Aesthetic surgery journal / the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic surgery. 2013;33(8):1099–109. doi: 10.1177/1090820X13510170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Scott AM, Pusic AL. Measuring outcomes that matter to face-lift patients: development and validation of FACE-Q appearance appraisal scales and adverse effects checklist for the lower face and neck. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2014;133(1):21–30. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000436814.11462.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Schwitzer JA, Scott AM, Pusic AL. FACE-Q scales for health-related quality of life, early life impact, satisfaction with outcomes, and decision to have treatment: development and validation. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2015;135(2):375–86. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Schwitzer JA, Baker SB, Carruthers A, Carruthers J, et al. Development and Psychometric Validation of the FACE-Q Skin, Lips, and Facial Rhytids Appearance Scales and Adverse Effects Checklists for Cosmetic Procedures. JAMA dermatology. 2016;152(4):443–51. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee EH, Klassen AF, Lawson JL, Cano SJ, Scott AM, Pusic AL. Patient experiences and outcomes following facial skin cancer surgery: A qualitative study. The Australasian journal of dermatology. 2016;57(3):e100–4. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burdon-Jones D, Thomas P, Baker R. Quality of life issues in nonmetastatic skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162(1):147–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guidance for industry: Patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Services UDoHaH, editor. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aaronson N, Alonso J, Burnam A, Lohr KN, Patrick DL, Perrin E, et al. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2002;11(3):193–205. doi: 10.1023/a:1015291021312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, Leidy NK, Martin ML, Molsen E, et al. Content validity--establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 1--eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value in health : the journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2011;14(8):967–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, Leidy NK, Martin ML, Molsen E, et al. Content validity--establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report: part 2--assessing respondent understanding. Value in health : the journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2011;14(8):978–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Schwitzer J, Scott A, Pusic AL. FACE-Q Scales for Health-Related Quality of Life, Early Life Impact and Satisfaction with Outcomes and Decision to Have Treatment: Development and Validation. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2014 doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khadka J, Gothwal VK, McAlinden C, Lamoureux EL, Pesudovs K. The importance of rating scales in measuring patient-reported outcomes. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2012;10:80. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andrich D. Controversy and the Rasch model: a characteristic of incompatible paradigms? Medical care. 2004;42(1 Suppl):I7–16. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000103528.48582.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wright B, M G. Rating Scale Analysis. Chicago, IL: Mesa Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrich D, Sheridan B. RUMM2030 (software program) RUMM Laboratory; Perth, Australia: 1997-2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hobart J, Cano S. Improving the evaluation of therapeutic interventions in multiple sclerosis: the role of new psychometric methods. Health technology assessment. 2009;13(12):iii, ix–x. 1–177. doi: 10.3310/hta13120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.G R Probabilistic Models for Some Intelligence and Attainment Tests. Copenhagen, Denmark: Danish Institute for Education Research; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sage, editor. Newbury Park, CA: 1988. D. A. Rasch Models for Measurement. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cronbach LJ. Coeffient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16(3):297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Streiner D, N G. Press OU, editor. Oxford: 2008. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kazis LE, Anderson JJ, Meenan RF. Effect sizes for interpreting changes in health status. Medical care. 1989;27(3 Suppl):S178–89. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155–9. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katz JN, Larson MG, Phillips CB, Fossel AH, Liang MH. Comparative measurement sensitivity of short and longer health status instruments. Medical care. 1992;30(10):917–25. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199210000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.J C Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dey JK, Ishii LE, Joseph AW, Goines J, Byrne PJ, Boahene KD, et al. The Cost of Facial Deformity: A Health Utility and Valuation Study. JAMA facial plastic surgery. 2016;18(4):241–9. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2015.2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sobanko JF, Sarwer DB, Zvargulis Z, Miller CJ. Importance of physical appearance in patients with skin cancer. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al] 2015;41(2):183–8. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waalboer-Spuij R, Hollestein LM, Timman R, van de Poll-Franse LV, Nijsten TE. Development and Validation of the Basal and Squamous Cell Carcinoma Quality of Life (BaSQoL) Questionnaire. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017 doi: 10.2340/00015555-2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Sahay AP, Sands LP. Measurement properties of Skindex-16: a brief quality-of-life measure for patients with skin diseases. Journal of cutaneous medicine and surgery. 2001;5(2):105–10. doi: 10.1007/BF02737863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mathias SD, Chren MM, Colwell HH, Yim YM, Reyes C, Chen DM, et al. Assessing health-related quality of life for advanced basal cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma nevus syndrome: development of the first disease-specific patient-reported outcome questionnaires. JAMA dermatology. 2014;150(2):169–76. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.5870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andrich D. Rating scales and Rasch measurement. Expert review of pharmacoeconomics & outcomes research. 2011;11(5):571–85. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cano SJ, Browne JP, Lamping DL, Roberts AH, McGrouther DA, Black NA. The Patient Outcomes of Surgery-Head/Neck (POS-head/neck): a new patient-based outcome measure. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2006;59(1):65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.