Summary

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of Class III medical devices can take from 3 to 7 years. Although this is shorter than times for drug approvals, patients with serious or life-threatening diseases and disorders may not have time to wait for device approval to access needed treatments. The FDA has a number of pathways, similar to drug approval processes, for expanded use of unapproved medical devices in patients for whom no reasonable alternative therapy is available. Additionally, the FDA regulates the manufacture and use of “custom” medical devices—those made for use by 1 specific patient. With the advent of 3-dimensional printing and bioprinting, new rules are evolving to address concerns that lines may be blurred between “custom” treatments and unregulated human experimentation.

Key Words: 3D printing, compassionate use, custom medical devices, device regulations, expanded access, FDA device approval, HDE, medical devices

Abbreviations and Acronyms: 3D, 3-dimensional; AM, additive manufacturing; CDE, custom device exemption; CUR, compassionate use request; DBS, deep brain stimulator(s); EA, expanded access; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; HDE, humanitarian device exemption; IDE, investigational device exemption; IRB, institutional review board; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; PMA, pre-market approval; TIDE, treatment investigational device exemption

As with drugs, in the United States, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval is required for the interstate transport and marketing of devices used in the treatment of human disease (1). Class I devices (e.g., bandages, hand-held surgical instruments) and Class II devices (e.g., infusion pumps, surgical drapes) present the lowest risk to patients and usually do not require clinical trials for marketing approval. Class III devices carry a significant risk of illness or injury, and usually require clinical trials. The approval process for Class III devices that have no “predicate” (i.e., a predecessor-approved device that is similar in function) and have passed preclinical bench and animal testing begins with the filing of an investigational device exemption (IDE). This exemption allows the device to be used in human trials. Further details of medical device classification and approvals, and the IDE application have been discussed in a previous review (1), and can be found at the FDA’s website (2). Once a device enters the clinical testing and approval process, the average time to market is 3 to 7 years (1).

Although the time to device approval is significantly shorter than the approval process for new drugs, it is nevertheless lengthy and could prevent patients from accessing device therapy when they most need it for “life-threatening or severely debilitating disease” or “serious diseases or conditions,” including “sight-threatening and limb-threatening conditions and situations involving irreversible morbidity” (3). Mechanisms have therefore evolved to allow expanded access (EA) to unapproved devices for emergency and nonemergency treatment of individuals and groups of patients.

Device approval and EA to nonapproved devices face additional issues that drug approvals do not. Drugs, once approved, may not then be chemically modified to meet individual patient requirements. Modification of many devices, such as medical implants, on the other hand, may be necessary for the treatment of a patient or patients whose needs are not met by the device in its strictly approved form. One example is an approved orthopedic implant or prosthetic device that is modified to fit the joint or limb of a patient who has special anatomy or requires it to be adapted to special use. Other examples include creation of custom vascular stents and other implants to meet unusual anatomic challenges. As the trend toward more personalized medical treatment evolves, and as evolving manufacturing methods such as 3-dimensional (3D) printing provide easier and rapid methods for device design and alteration, custom device therapy is likely to become more and more common.

This review examines the regulatory pathways by which an investigational device or implant that has not begun and/or completed clinical testing can be accessed for patients in urgent need; reviews some of the rules regarding how and when an already approved device may be modified from its strictly approved form for use in an individual patient; and explores future regulatory concerns for personalized devices created in 3D printing processes.

The Changing Regulatory Landscape

As the world’s oldest consumer protection agency (4), the FDA’s primary missions are to assure the efficacy and safety of both drug- and device-based medical therapies. When individual patient need is urgent, and no comparable effective therapy is available, the agency faces a challenge to provide reasonable assurances that devices are both safe and effective, while acknowledging that some patients face markedly elevated risks or disabilities from their own disease or disorder and may be willing to accept significantly higher risks in pursuit of treatment. On the other hand, FDA oversight also serves to prevent deliberate or inadvertent misuse of devices in vulnerable patient populations to further purely commercial interests.

Specific FDA pathways for EA to unapproved medical devices include a compassionate use request (CUR), custom device exemptions (CDEs), and the humanitarian device exemption (HDE). Each of these pathways has unique characteristics that are important to understand in order to determine which is the most appropriate process for use of a specific unapproved device.

Since the 1976 amendments to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act, there have been multiple changes to the FDA rules and regulations regarding the acquisition by physicians of unapproved medical devices for patients facing unique, unusual, or urgent/emergent circumstances.

Compassionate Use Requests

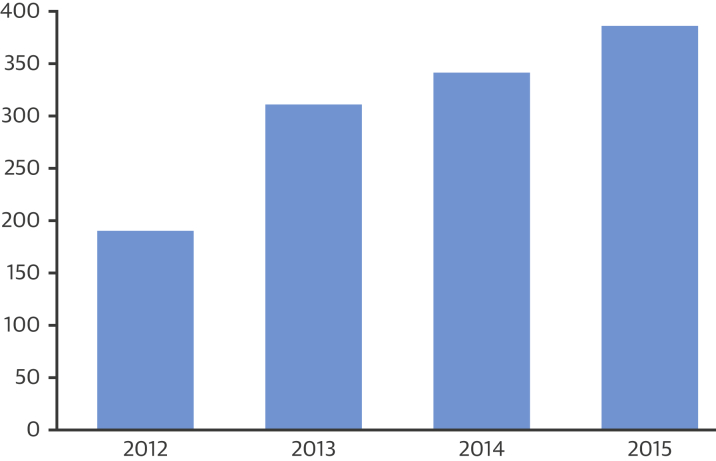

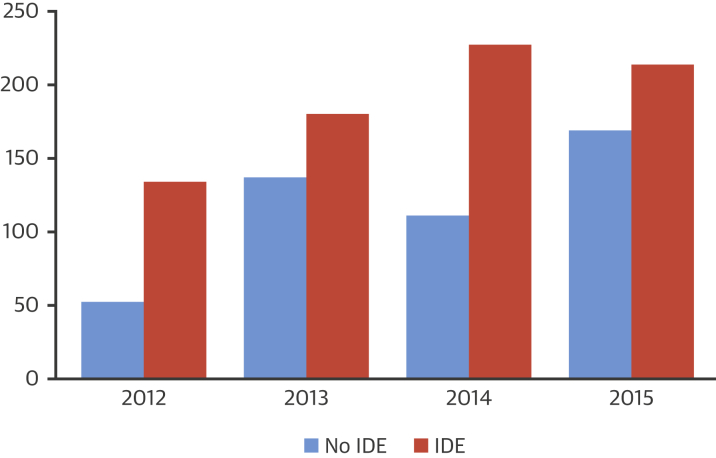

The FDA uses the term “expanded access” rather than “compassionate use” to define access to unapproved drugs or devices outside of clinical testing. EA, even if it involves a group of patients, rather than an individual patient, differs significantly from clinical studies of the device; EA is not “research” and does not have the primary purpose of generating performance, efficacy, and safety data. Overall, the number of submissions for compassionate use of devices is trending upward (Figure 1). Consistently, use of devices with an IDE (i.e., those in clinical trial phases) have been requested more often than those without an IDE (those not yet entered in clinical trials) (Figure 2). Approximately 99% of all requests for EA to devices with an IDE are granted by the FDA. Even EA to devices without an IDE are granted in 98% to 99% of cases (Table 1) 5, 6.

Figure 1.

Total FDA Submissions for Compassionate Use of Medical Devices, 2012 to 2015∗

FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration. ∗See reference (5).

Figure 2.

FDA CURs for Devices With IDEs Versus Without IDEs

CUR = compassionate use request; FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; IDE = investigational device exemption.

Table 1.

FDA Approval Rates for Compassionate Use of Medical Devices

| Year | With IDE | Without IDE |

|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 99.19 | 98.11 |

| 2013 | 98.86 | 91.79 |

| 2014 | 99.54 | 99.01 |

| 2015 | 99.04 | 98.80 |

Values are %. See reference (5).

FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; IDE = investigational device exemption.

When a request is made to use an unapproved device for treating a patient, the appropriate EA pathway depends on whether or not an IDE has been filed for the device, and whether the use involves treatment of a life-, limb-, or sight-threatening emergency (Table 2).

Table 2.

FDA Pathways for Use of Unapproved Medical Devices∗

| EA Pathway | Criteria for Use | When Can It Be Used? | No. of Patients to Be Treated | FDA Approval Needed? | How Is FDA Approval Obtained | Patient Protection Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency use |

|

Before or after initiation of clinical trials | Individual or few patients | No: submit report to FDA within 5 days after treatment | N/A |

|

| Compassionate use |

|

While clinical trials are ongoing | Individual patient or small patient groups | Yes | IDE supplement including:

|

|

| Treatment IDE |

|

During (within) a clinical trial | Wide access depending on patient/physician need | Yes | Treatment IDE supplement, including:

|

|

| Continued access: patients are allowed continued access to a investigational device during pre-marketing application and review |

|

After completion of a clinical trial | Same rate of enrollment as for study | Yes | IDE supplement, including:

|

|

Emergency expanded use

As with EA to investigational drugs, the FDA provides a pathway for emergency use of an unapproved device. Emergency use reports can be submitted both for those without an IDE, as well as for devices that are in clinical trials under an IDE.

Criteria for allowable emergency use are: 1) the patient has a life-threatening or serious disease or condition that needs immediate treatment; 2) no generally acceptable alternative treatment for the condition exists; and 3) because immediate use is needed in a critical situation, there is no time to obtain FDA approval for the use. The FDA now considers that limb-threatening, and sight-threatening diseases, situations involving irreversible morbidity, and those that constitute “life-threatening or serious conditions” as qualifying for EA 2, 3. When these criteria are met, an unapproved device may be used without prior permission of the FDA. The treating physician need not have clinical data regarding the device to proceed, but must have “substantial reason to believe” that benefit will occur from use of the device. The FDA expects the physician to “follow as many patient protection procedures as possible.” These include obtaining informed consent from the patient or their legal representative, obtaining clearance from their institution as specified in the institutional policies, obtaining concurrence of the institutional review board (IRB) chairperson at their institution, obtaining an independent assessment and concurrence from an uninvolved physician, and obtaining authorization from the device manufacturer 2, 5. If an IDE exists for the device, then the IDE sponsor (investigator or manufacturer) must notify the FDA of the emergency use within 5 days after its use through submission of an IDE report. This usually takes the form of a “Deviations From the Investigational Plan” report under the existing IDE and includes a summary of the conditions constituting the emergency, the patient protection measures that were followed, and patient outcome information (6). If no IDE exists, the physician should submit a follow-up report to the FDA within 5 days of treatment that includes a description of the device, details of the case, and the patient protection measures that were followed. This report can be sent to: Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, 10903 New Hampshire Avenue, Document Control Center, W066 Rm G-609, Silver Spring, Maryland 20993.

Nonemergency expanded use

In nonemergency EA of an investigational device for an individual patient, the process begins when a physician requests use of the device from its manufacturer, because the FDA cannot compel a manufacturer to provide a nonapproved device for patient use. If the manufacturer agrees to provide the device, there are 2 “pathways” to obtain FDA approval for nonemergency EA, depending on whether there is an existing IDE for the device or not. In either case, the physician should not treat the patient without prior FDA approval for use of the device. The physician must also in both cases devise an appropriate schedule for monitoring the patient to detect any problems arising from use of the device. After treatment, a follow-up report must be sent to the FDA.

Devices with IDEs

If the device is subject to an IDE, the sponsor of the IDE (e.g., the investigator, physician, or manufacturer) should submit an IDE supplement that requests approval for EA. Elements that should be included in the supplement are found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Elements in the IDE Supplement for Expanded Use of an Investigational Device

|

|

|

|

Abbreviations as in Table 2.

In some cases, the IRB will not give final approval until FDA approval is obtained. In that case, the request should indicate that IRB approval will be obtained before use of the device. Proof of approval by the IRB chairperson must be submitted with the follow-up report after the patient is treated.

Devices without IDEs

If there is no IDE for the device, the physician or manufacturer (because there is no investigator) submits a request including all of the information that would be included in an IDE supplement, except deviations from approved clinical protocols (because there are no “approved protocols” in the absence of an IDE) (Table 3). Assistance for submission of a request for expanded use of a device without an IDE can be obtained by contacting: CDRHExpanded-Access@fda.hhs.gov.

More than 1 patient will be treated

If the treatment is being requested for more than 1 patient, the physician follows the same processes outlined in the preceding text, but should additionally include the number of patients to be treated. If there is an IDE in place, the IDE supplement should then also include a protocol for treatment, or identify deviations from the existing IDE clinical protocol(s). After treatment of all patients, a follow-up report must be submitted to the FDA and to the IRB that includes information on patient outcomes.

The treatment IDE

An approved IDE specifies the number of sites and maximum number of human subjects to be enrolled in the clinical trial. If during the course of the trial data suggests that the device is effective, the ongoing trial can be expanded to include additional patients with life-threatening or serious disease. An expansion of a clinical trial under these circumstances is called a “treatment use” and requires submission of a treatment IDE (TIDE). Criteria for a TIDE are summarized in Table 4 (5).

Table 4.

Criteria for Treatment IDE

|

|

|

|

IDE = investigational device exemption.

An “immediately life-threatening” disease refers to a disease in which there is a reasonable likelihood that death will occur within months or in which premature death is likely without early treatment.

Because an IDE is in place, the application for a TIDE must be made by the IDE sponsor (investigator, physician, or manufacturer). The contents of the application, in the designated order, are provided in Table 5. Treatment may begin 30 days after the FDA receives the TIDE submission unless the FDA otherwise notifies the sponsor before 30 days. The FDA can approve the application as written or approve with modifications.

Table 5.

Contents (in Order) for TIDE Application

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Applications should be identified on the outside of the envelope as a T IDE application, and reference the original IDE number. An original and 2 copies should be submitted to: Food and Drug Administration, enter for Devices and Radiological Health, Document Mail Center. W066-G609, 10903 New Hampshire Avenue, Silver Springs, Maryland 20993-0002.

TIDE = treatment investigational device exemption; other abbreviations as in Table 2.

FDA disapproval, or later withdrawal of approval, can occur for a variety of reasons: 1) the application does not meet approval criteria; 2) the FDA determines that any of the grounds for disapproval or withdrawal of approval apply (Table 6); 3) there are insufficient safety and efficacy data to support use of the device; 4) available scientific evidence taken as a whole fails to provide a reasonable basis to conclude that the device will be effective for its intended use in the intended patient population or to conclude that the device would not expose the intended patients to an unreasonable and significant additional risk of illness or injury; 5) there is reasonable evidence that the TIDE is impeding enrollment in or otherwise interfering with conduct or completion of a controlled trial of the same or another investigational device; 6) the device has received approval, or a comparable device or therapy becomes available to treat or diagnose the same condition in the same patient population; 7) the sponsor is not diligently pursuing marketing approval; 8) approval of the IDE has been withdrawn; or 9) the clinical investigators are not qualified to use the device for the intended treatment (7).

Table 6.

FDA Grounds for Disapproval or Withdrawal of Approval of a Device

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abbreviations as in Table 2.

If a TIDE is granted, the sponsor must submit progress reports, including adverse event reports, on a semiannual basis to all reviewing IRBs and the FDA until the filing of a marketing application. After filing of a marketing application, reports to the FDA are due annually.

Humanitarian Device Exemption

A humanitarian device is one that is expected to diagnose or treat conditions affecting very small groups of patients. The 20th Century Cures Act (8) recently amended the size of the population required to qualify for Humanitarian Use Designation from fewer than 4,000 to “not more than 8,000 individuals” in the United States annually (9). Because so few individuals are affected by the disease or conditions to be treated, it could take years to locate and recruit sufficient numbers of patients to provide sufficient power in clinical controlled trials to attain statistical significance. Therefore, evidence of scientific efficacy is not required for humanitarian use, and sponsors need only show that there is a probable benefit to health and that the probable benefit outweighs the risks of injury or illness from the device. Further details about HDEs can be found in a previous review in the Journal (1). HDEs are handled through the Office of Orphan Products Development at the FDA.

Apart from concerns that HDEs may not sufficiently guarantee patient safety or efficacy because clinical trials are not required, some authors have questioned whether manufacturers have exploited HDEs for market advantage. For example, deep brain stimulators (DBS) emerged as a possible treatment for neuropsychiatric disorders. In 2009, the FDA granted Medtronic corporation an HDE to use one of their DBS devices to treat refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Some authors have noted that there are an estimated 440,000 to 660,000 patients in the United States with chronic, severe, treatment-resistant OCD, more than enough to run a small randomized clinical trial (10). In fact, at the time the HDE was granted, there was a clinical trial underway at the National Institutes of Health to test DBS for OCD, under an IDE. An HDE allows marketing of an untested device; the manufacturer can bypass the steep FDA pre-market approval (PMA) fees ($271,787 in 2009), as well as avoid the costs and the years-long delay to bring a device to market due to clinical trials (10). According to Fins et al. (10), undisclosed sources suggest that through the HDE, Medtronic recovered $10 million from the initial research and development costs, and developed “good relationships” with physicians in the field—in other words, generated publicity within the specialty and established a marketing base.

Custom Device Exemptions

The 1976 Medical Device Amendments of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act of 1938 provided for a CDE, that allows customization of approved devices, and creation of custom devices outside of clinical trials to serve individual needs 11, 12. Custom devices can be either “patient-centric,” meaning they are used in the treatment of a patient, or “physician-centric,” meaning they meet the special needs of a physician or the physician’s practice. An example of a physician-centric custom device might be modification to an existing device to fit an individual physician’s physical disabilities. This review focuses on patient-centric devices, although many of the same principles and processes also apply to physician-centric devices.

Congress was clear in intending that the CDE amendment would allow physicians to provide care only for individual patients whose needs could not be met by devices currently on the market. The Senate Committee report on the amendment stated, “It is the intent of these provisions to allow physicians to order custom-made products but not to permit manufacturers to circumvent standards-setting and scientific review requirements by commercially exploiting these products” (13). A legislative distinction was drawn between “customized” and “custom” devices. A custom device is intended for only 1 patient, whereas a customized device is one that is widely disseminated, but can, on the order of a physician, vary in size, shape, or material to meet the needs of an individual patient 13, 14. If a practitioner uses a custom patient-centric device in the general “course of conduct” of their practice on multiple patients, a CDE is not applicable, and the practitioner can be sanctioned. The House Committee report on the amendment stated, “[Custom] devices are not exempt from otherwise applicable provisions of the proposed legislation, such as provisions regarding investigational use, banning, restriction, adulteration or misbranding.” The legislation explicitly allowed the FDA to take action against a physician “when a practitioner’s use of a custom device is repeated to such an extent that the practitioner is in effect conducting unsupervised experiments or is otherwise using a device in violation of the act” (13). It is nevertheless often difficult to draw distinctions between compassionate use and human experimentation, and exert the appropriate regulatory controls.

An example of the blurring of these distinctions is the case of Italian surgeon Paolo Macchiarini, who implanted the first tracheobronchial biometric devices for tracheal stenosis and other disorders of the trachea into patients who had failed conventional medical therapy and sought desperate solutions. Dr. Macchiarini began by implanting cadaveric trachea that had been stripped and colonized by the recipient’s stem cells, and progressed to using fully synthetic trachea seeded with the recipient’s stem cells. Despite dismal results (7 of 8 patients died), his work continued, and he recruited relatively healthier patients for operations in Sweden, Russia, Britain, Spain, and the United States, with continued deaths. When Macchiarini was accused of violating Swedish law because he did not obtain legally required ethical review before performing his surgeries, he responded by arguing that the surgeries were performed “for health reasons” and not as research, and that he consulted the Medical Products Agency (a Swedish counterpart to the FDA) and the Regional Ethics Committee, confirmed the patient had no other therapeutic options, and obtained approval from the chairman of the Ethics Council of Karolinska University Hospital where the operations were to be performed 15, 16—steps similar to those required by the FDA and considered allowable for treatment of patients with life-threatening and serious disease using unapproved medical devices. This and other cases, such as the Medtronic DBS raise cautionary flags about potential misuses of compassionate device exemptions and HDEs to circumvent FDA regulatory oversight, bypass patient safety protections, and award device manufacturers unique marketing opportunities (10).

Although the CDE has been available for over 40 years, specific guidance and rules regarding CDEs have only recently been released by the FDA. Thus, laws and regulations regarding the CDE developed largely as a result of compliance actions taken by the FDA against custom devices over the years, or through other litigation history. The FDA differentiation of custom versus customized devices can be seen in the case of Contact Manufacturers Association v. FDA, 1985, for example (17). Contact Manufacturers argued that contact lenses were a custom device, because each individual patient required an individualized prescription from a health-care professional who had examined the patient’s eyes. The court sided with the FDA, stating that contact lenses were generally available to or used by many physicians. The FDA pointed out that a contact lens prescription was a simple variation among an “approved range of powers and anterior and posterior surface contours,” and “prescriptions for all but the most pathological eyes are likely to replicated again and again and are thus ‘generally used’” 13, 17. Thus, devices that are individualized to some extent may be considered customized rather than custom and not qualify for a CDE. A customized device must go through the normal PMA process for devices, including clinical trials, if approval via a PMA or 501(k) can be broad enough to cover a usual range of variations to meet individual patient needs. Examples of characteristics that may qualify a device as custom rather than customized and avoid the PMA process are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Characteristics of Devices that May Qualify as “Custom” Vs. “Customized”

|

|

|

|

|

Subsequently, the passage of the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act in 2012 created significant changes in custom device regulations, although it took 2 years for the FDA to release their guidance with regard to these changes. Then in October of 2016, the FDA released final rules that amended its definition of custom devices (Table 8) 18, 19, 20. New provisions for a CDE included the following limitations: 1) the device is for the purpose of treating a “sufficiently rare condition, such that conducting clinical investigations on such device would be impractical”; 2) the production of the device must be limited to no more than 5 units per year of a particular device type; and 3) a manufacturer is required to submit an annual report to the FDA on the custom devices it has supplied to physicians and patients (18). A summary of the FDA’s decision tree on whether a device is custom can be found in Table 9 (21). The FDA clarified that it now considers CDEs on a per patient rather than per use basis, thus allowing, for example, for bilateral custom orthopedic implants in the same patient to be treated by the manufacturer as only 1 occurrence, provided that both devices are ordered within the same reporting year 21, 22. Further, once a device is considered a valid custom device, further modifications are still allowable under the original case, provided the modifications are performed in order to meet the individual patient’s special needs 21, 22.

Table 8.

Congressional Definition of a “Custom Device”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FDCA = Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act.

Table 9.

Patient-Centric Custom Device: Requirements

| Modified in response to an order of a qualified provider |

| “Necessarily deviates”∗ from an otherwise applicable performance standard such that investigations would be impractical |

| Not generally available for commercial distribution in the United States from a manufacturer, importer, or distributor |

| Designed to treat a unique pathological or physiological condition, or intended for use by a single patient named in the order of the qualified practitioner |

| Assembled from components made on a case-by-case basis |

| Intended for treatment of a “sufficiently rare”† condition |

| Produced in fewer than 5 units per yr‡ |

FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

“Necessarily deviate” is defined by the FDA as a device that is modified to be sufficiently unique that clinical investigations would be impractical and could not be done to prove conformance to applicable performance standards and/or to support a premarket review.

”Sufficiently rare condition” is defined by the FDA as a condition in a patient population in which the incidence and prevalence is so small that conducting clinical trials would be impractical.

See text for further details defining 5 units per yr.

Allowing more than 1 iteration of a custom device under a CDE raises an interesting issue about storage of custom devices. “Storage” implies the presence of an inventory, which in turn raises questions of whether a device is actually custom. But there may nevertheless be situations in which a truly custom product that has been designed for a single patient may nevertheless require multiple iterations (13). Take, for example, the use of an innovative and customized heart valve. The surgeon may be unsure of the exact size needed for the patient until in the middle of the operation—he or she may thus request that the custom device be created in several sizes for intraoperative selection. FDA rules allow the manufacture of more than 1 device in these situations but requires that once a properly sized device is chosen, the unused devices must be returned to the manufacturer and/or destroyed, and the physician must provide a statement certifying that this has been done (21). A device may become ineligible to be treated as a custom device under a CDE if the manufacturer stockpiles too many of them (13).

CDE Requests

The regulatory process for custom devices begins with a physician request to a manufacturer to create/supply the device, and agreement with the manufacturer to begin a CDE application and develop a reporting schedule to the FDA. The manufacturer (not the FDA) is responsible for the initial determination of whether the device meets all of the CDE criteria or not. The manufacturer then reports its decision in its annual submission to the FDA (sometimes after the device has been used), no later than March 31st of the following year (20), at which time the FDA determines whether it concurs with the manufacturer’s determination. Use of a device that meets all the requirements for a CDE does not require prior FDA approval, but does require the informed consent of the patient or their legal representatives. The FDA further recommends that as many of the patient protection measures included in Table 3 be instituted as possible (23). CDEs carry an annual reporting requirement to the FDA. Required elements of the annual report for patient-centric custom devices can be found in Table 10.

Table 10.

Required Elements of the Annual Report to the FDA for Patient-Centric Custom Device

|

|

|

The FDA defines a “necessary deviation” as a device that has been modified to be sufficiently unique so that clinical investigations would be impractical and could not be performed to demonstrate that it conforms to applicable performance standards and/or to support a pre-market review.

What happens if the FDA determines that a device that was used for patient treatment did not meet CDE requirements? According to the FDA information webinar on CDEs, the FDA notifies the manufacturer in writing the reasons why the device does not qualify for a CDE, with the primary focus of “helping manufacturers [to] implement the Custom Device Exemption correctly and efficiently,” however, “the FDA will consider taking enforcement actions when the situation calls for it” (20). Over the years, the FDA has sent warning letters to several companies alleging that their “custom” devices were in fact customized rather than custom and did not in fact qualify for the exemption. One example is the case of Inter-OS Technologies Inc.—a manufacturer of dental implants—in which the FDA alleged that 2 patients had been implanted with the same prototype device. Although each had been “customized,” the device itself was of the same design, which was not created specifically for each patient (24). Because the device was denied custom designation, a number of other violations were deemed to therefore have occurred. The company was accused of failing to obtain informed consent for the implants, and of failure to obtain FDA and IRB approval before enrolling and treating patients—which are required with customized, but not custom, devices. Similarly, the company was accused of failure to adhere to the responsibilities of investigators and sponsors, failure to have written monitoring procedures in place, and failure to maintain device accountability records. Additional accusations were that the company implanted a third patient after further device modification, and only then submitted an IDE to the FDA, which was disapproved. They were then alleged to have implanted a fourth patient after disapproval of the IDE (25). The company was given 15 days to respond with specific corrective steps (25).

Compassionate Use Requests

CURs permit timely review of a custom device that is intended for the unique or unusual circumstance of a particular patient, or a customized device that does not meet all criteria for a CDE. In many cases, CURs can be approved in <30 days by the FDA (22). The manufacturer is required to provide a monitoring schedule for the device and a follow-up report after the patient has been treated.

CURs can also be used to access devices that are under investigation in pre-market studies: 1) when an investigational device is desired for a unique use that is inconsistent with the approved investigational plan for a device; 2) when a physician who is not part of the clinical investigation is making the request; or 3) when a physician wishes to treat a patient or group of patients who have a serious disease or condition for which no alternative, legally marketed device exists that adequately addresses the medical need. When access to an investigational device is being sought under a CUR, the physician must either access the IDE through requests to the manufacturer or investigator, or must file an investigator IDE him- or herself. The manufacturer must submit a supplement to their existing IDE that details the number of patients to be treated, the treatment protocol, and any deviations that are expected from their approved IDE protocol. Treatment under a nonemergency CUR cannot proceed without prior approval of the FDA. As with CDEs, CURs require both a monitoring schedule and follow-up reports to the FDA (5).

Emergency Use Requests

In rare instances in which an acute condition is life-, limb-, or sight-threatening, and there is no time for FDA approval, emergency use of an unapproved custom device may be needed before an IDE is approved. In such cases, similar to emergency use of unapproved, noncustom devices, the physician may go ahead and treat the patient but must notify the FDA within 5 days of the emergency use, by submitting an IDE report that includes the case details and patient protection measures (Table 3) that were followed.

On-Demand, Custom, and Patient-Matched 3D-Printed Medical Devices

3D printing (also called additive manufacturing [AM]) has entered the manufacturing stream for medical devices (26), although until recently, custom 3D printing was used primarily for education. Since 2010, however, an explosion of interest in 3D-printed devices is evident in the published reports, with a remarkable 20-fold increase in publications indexed by PubMed between 2010 and 2016 (27). Both clinical and regulatory issues concerning custom devices created via 3D printing are complex and evolving rapidly (28).

In cardiovascular medicine, 3D printing of a patient’s anatomic structures constructed from data obtained in medical scans (computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging) has been used, for example, to check sizing of treatment devices and to clarify complex anatomic variation that may affect surgical planning for device placement or facilitate the creation of a custom device (29). It is not clear at this time whether such 3D-printed materials are “devices” or should rather be classified as a form of “3D imaging,” that is, another type of clinical documentation (27). In a few instances, teaching hospitals have used custom 3D printing to produce devices for patient implantation, (also referred to as “patient-matched” devices), the use of which generally follows established FDA custom device regulations (30). 3D printing of matrices embedded with living cells and other elements, so-called “bioprinting,” presents the potential for creating complex tissue architectures 26, 31, 32, 33, 34 and for producing tissues or even organs for transplantation 35, 36.

Rules and regulations regarding implanted 3D-printed devices, particularly those that involve biomechanical hybridization, are in their infancy, whereas device development leaps ahead. The FDA announced rules changes for custom medical devices in 2016 that included a few clarifications for on-demand and one-off 3D-printed devices. In cases where a hospital creates a 3D-printed custom device, for example, the hospital becomes the designated “manufacturer” that is governed by the amended rules 37, 38.

There has been some confusion in the published reports about FDA device classification of a 3D-printed treatment apparatus, with at least 1 group of authors erroneously implying that the FDA has classified them as low-risk, class II devices (27). 3D device classifications generally follow the same processes within the FDA as devices made by other manufacturing means, and vary depending on the device’s function, whether it will be implanted into a patient, and whether it carries the potential for significant harm. Most implanted devices are considered by the FDA to be class III, requiring preclinical laboratory and animal testing, and (usually) clinical trials.

In December of 2017, the FDA issued guidance on the manufacturing processes and regulation of AM devices (30). The FDA further emphasizes that “in general, if the type of characterization or performance testing is needed for a device that is made with non-AM techniques, the information should also be provided for an AM device of the same device type” (30). Thus, in any expanded use application, whether it be nonemergency compassionate use, treatment IDE, humanitarian use, or customized devices, similar manufacturing details will be required by the FDA regardless of whether or not the device is made by more traditional manufacturing processes or via AM.

Misuse of Compassionate Use Pathways

The laudable goal of EA pathways is to provide vulnerable patients who have few alternatives access to unapproved treatments. But concerns abound when the treatment use of unproven medical devices bypasses normal regulatory oversight. Because unapproved treatments come with incomplete data, or even totally lack clinical data to support their use, concerns over exploitation of vulnerable patients for the gain of commercial entities are reasonable. From a practical standpoint, EA pathways allow manufacturers access to patients, but do not generally provide researchers with improved access to subjects, because the underlying purpose of EA pathways is not scientific, but humanitarian. Sound scientific data are generally not produced in EA “episodes,” and these uses, therefore, do not usually further knowledge about experimental treatments in rigorous ways that benefit others with similarly desperate conditions. In addition, manufacturers could use, and potentially have used, EA exemptions to achieve simpler, cheaper, and more rapid approval compared with the more expensive and prolonged randomized clinical trials required under an IDE, such as in the Humanitarian Use Designation exemption described previously (10).

Finally, a serious concern regarding compassionate use of drugs and devices is that desperate patients seeking life-saving treatment could become victims of exorbitant pricing to access treatments they need. In response, FDA regulations state that pricing of devices for compassionate use must be based on “manufacturing and handling costs only” (39).

Summary

Patients with life-threatening or serious diseases, including limb- and sight-threatening disorders, can obtain EA to unapproved medical devices via pathways that parallel pathways for use of unapproved drugs. Emergency treatment of patients for whom no reasonable alternative treatment is available and for which there is no time to obtain FDA approval can proceed without prior FDA approval, but requires notification of the FDA within 5 days of treatment. Nonemergent EA use for patients who have serious or life-threatening diseases and no reasonable alternative involves either submission to an existing IDE (if one exists) or submission of a written request containing the same information (when an IDE does not exist). Requests for EA are granted in 98% to 99% of cases. When EA is sought within a clinical trial (i.e., results suggest the trial should be opened to more patients), EA is obtained by submission of a treatment IDE. Humanitarian use of unapproved devices is a special pathway for patients suffering from life-threatening or serious diseases that are sufficiently rare that clinical trials would be impractical or impossible.

Custom devices can be used in individual patients without going through the PMA process, but must meet strict criteria to be classified as custom versus customized. Finally, 3D printing, including bioprinting, poses special challenges to regulators. Because these devices are easily made and altered to individual use, use of 3D printed devices can potentially blur the regulatory lines between approved custom devices, and human experimentation.

Footnotes

Dr. Van Norman has received financial support from the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The author attests she is in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors' institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACC: Basic to Translational Scienceauthor instructions page.

References

- 1.Van Norman G. Drugs, devices, and the FDA: part 2. An overview of approval processes: FDA approval of medical devices. J Am Coll Cardiol Basic Trans Science. 2016;1:277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Device Advice: Investigational Device Exemption (IDE). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/HowtoMarketYourDevice/InvestigationalDeviceExemptionIDE/default.htm. Accessed May 31, 2018.

- 3.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance on IDE Policies and Procedures. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/ucm080202.htm. Accessed June 23, 2018.

- 4.Van Norman G.A. Drugs, devices and the FDA: part 1: an overview of approval processes for drugs. J Am Coll Cardiol Basic Trans Science. 2016;1:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Expanded Access for Medical Devices. January 1, 2018. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/howtomarketyourdevice/investigationaldeviceexemptionide/ucm051345.htm. Accessed June 2, 2018.

- 6.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. IDE Reports. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/HowtoMarketYourDevice/InvestigationalDeviceExemptionIDE/ucm046164.htm#fda_action. Accessed July 18, 2018.

- 7.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Action on IDE Applications. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/HowtoMarketYourDevice/InvestigationalDeviceExemptionIDE/ucm046164.htm. Accessed July 18, 2018.

- 8.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 20th Century Cures Act. Authenticated U.S. Government Information. Government Printing Office. November 30, 2016. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/forindustry/developingproductsforrarediseasesconditions/designatinghumanitarianusedeviceshuds/default.htm. Accessed June 23, 2018.

- 9.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Designating Humanitarian Use Device (HUD). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/forindustry/developingproductsforrarediseasesconditions/designatinghumanitarianusedeviceshuds/default.htm. Accessed June 23, 2018.

- 10.Fins J.J., Mayberg H.S., Nuttin B. Misuse of the FDA’s humanitarian device exemption in deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:302–311. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.94th U.S. Congress (December 11, 1975). H.R.11124: Medical Device Amendments. U.S. House of Representative Bill Summary & Status. Library of Congress. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/94th-congress/house-bill/11124. Accessed June 20, 2018.

- 12.Medical Device Amendments of 1976. Public Law 94-295, May 28, 1976. Available at: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-90/pdf/STATUTE-90-Pg539.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2018.

- 13.Klepinski R.J. Old customs, ancient lore: the development of custom device law through neglect. Food Drug Law J. 2006;61:237–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodlee D. Understanding the US FDA’s custom device exemption. Practical solutions for handling the sale of patient-specific devices in the USA. J Med Device Reg. 2011;8:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macchiarini Did Not Obtain Necessary Ethics Approval, Says Swedish Research Council. Retraction Watch. May 2, 2016. Available at: https://retractionwatch.com/2016/05/02/macchiarini-did-not-apply-for-ethical-review-swedish-research-council/. Accessed June 16, 2018.

- 16.Kremer W. Paolo Macchiarini: A Surgeon’s Downfall. BBC World Service. September 10, 2016. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-37311038 Accessed June 16, 2018.

- 17.Contact Manufacturers Association v. FDA; 766 F.2d.592 (D.C. Cir. 1985).

- 18.Brennan Z. FDA Amends Definition of a Custom Device. Regulatory Focus. October 11, 2016. Available at: https://www.raps.org/regulatory-focus™/news-articles/2016/10/fda-amends-definition-of-custom-device. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- 19.Office of the Federal Register. Medical devices; custom devices; technical amendment. A rule by the Food and Drug Administration on 10/12/16. Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/10/12/2016-24438/medical-devices-custom-devices-technical-amendment. Accessed June 23, 2018.

- 20.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Custom Device Exemption (webinar). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Training/CDRHLearn/UCM418838.pdf. Accessed June 23, 2018.

- 21.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Custom Device Exemption: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. September 14, 2014. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/UCM415799.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2018.

- 22.Mihalko W.M. How do I get what I need? Navigating the FDA’s custom, compassionate use, and HDE pathways for medical devices and implants. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:919–922. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Information Sheet Guidance for Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), Clinical Investigators, and Sponsors. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/scienceresearch/specialtopics/runningclinicaltrials/guidancesinformationsheetsandnotices/ucm113709.htm. Accessed June 20, 2018.

- 24.Davis J, Gibbs J. The Custom Device Exemption: What Is It and Does It Ever Apply? September 1, 2009. Medical Device and Diagnostic Industry. Available at: https://www.mddionline.com/custom-device-exemption-what-it-and-does-it-ever-apply. Accessed June 23, 2018.

- 25.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Warning Letter to Randolph Robinson MD, DDS, President, Inter-Os Technologies, Incorporated. Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration. June 20, 2003. Available at: http://www.circare.org/fdawls2/interos_20030720.pdf. Accessed June 23, 2018.

- 26.Di Prima M., Coburn J., Hwant D., Kelly J., Khairuzzaman A., Ricles L. Additively manufactured medical products—the FDA perspective. 3D Print Med. 2016;2:1. doi: 10.1186/s41205-016-0005-9. https://threedmedprint.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s41205-016-0005-9 Available at: Accessed June 23, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luo H., Meyer-Szary J., Wang Z., Sabiniewicz R., Liu Y. Three-dimensional printing in cardiology: current applications and future challenges. Cardiology J. 2017;24:436–444. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2017.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morrison R.J., Kashlan K.N., Flanagan C.L. Regulatory considerations in the design and manufacturing of implantable 3D-printed medical devices. Clin Trans Sci. 2015;8:594–600. doi: 10.1111/cts.12315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sodian R., Schmauss D., Schmitz C. 3-dimensional printing of models to create custom-made devise for coil embolization of an anastomotic leak after aortic arch replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:974–978. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Technical Considerations for Additive Manufactured Medical Devices: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/UCM499809.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- 31.Kolesky C.B., Homan K.A., Skylar-Scott M.A., Lewis J.A. Three-dimensional bioprinting of thick vascularized tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:3179–3184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521342113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J.Z., Li Z.Y., Zhang J.P., Guo X.H. Could personalized bio-3D printing rescue the cardiovascular system? Int J Cardiol. 2016;223:561–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.08.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vukicevic M., Mosadegh B., Min J.K., Little S.H. Cardiac 3D printing and its future directions. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2017;10:171–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bartel T., Rivard A., Jimenez A., Mestres C.A., Muller S. Medical three-dimensional printing opens up new opportunities in cardiology and cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:1246–1254. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee V.K., Dai G. Printing of three-dimensional tissue analogs for regenerative medicine. Ann Biomed Eng. 2017;45:115–131. doi: 10.1007/s10439-016-1613-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duan B. State-of-the-art review of 3D bioprinting for cardiovascular tissue engineering. Ann Biomed Eng. 2017;45:195–209. doi: 10.1007/s10439-016-1607-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fornell D. FDA changes rules for custom medical device exemptions. Diagnostic and Interventional Cardiology. October 13, 2016. Available at: https://www.dicardiology.com/article/fda-changes-rules-custom-medical-device-exemptions. Accessed June 1, 2018.

- 38.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 3D Printing of Medical Devices. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/3DPrintingofMedicalDevices/default.htm. Accessed June 20, 2018.

- 39.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. CFR-Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. 21CFR812. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfCFR/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=812&showFR=1. Accessed June 1, 2018.