Abstract

Background

End-of-life care is a prominent consideration in patients on maintenance dialysis, especially when death appears imminent and quality of life is poor. To date, examination of race- and ethnicity-associated disparities in end-of-life care for patients with ESRD has largely been restricted to comparisons of white and black patients.

Methods

We performed a retrospective national study using United States Renal Data System files to determine whether end-of-life care in United States patients on dialysis is subject to racial or ethnic disparity. The primary outcome was a composite of discontinuation of dialysis and death in a nonhospital or hospice setting.

Results

Among 1,098,384 patients on dialysis dying between 2000 and 2014, the primary outcome was less likely in patients from any minority group compared with the non-Hispanic white population (10.9% versus 22.6%, P<0.001, respectively). We also observed similar significant disparities between any minority group and non-Hispanic whites for dialysis discontinuation (16.7% versus 31.2%), as well as hospice (10.3% versus 18.1%) and nonhospital death (34.4% versus 46.4%). After extensive covariate adjustment, the primary outcome was less likely in the combined minority group than in the non-Hispanic white population (adjusted odds ratio, 0.55; 95% confidence interval, 0.55 to 0.56; P<0.001). Individual minority groups (non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic Native American, and Hispanic) were significantly less likely than non-Hispanic whites to experience the primary outcome. This disparity was especially pronounced for non-Hispanic Native American and Hispanic subgroups.

Conclusions

There appear to be substantial race- and ethnicity-based disparities in end-of-life care practices for United States patients receiving dialysis.

Keywords: end stage kidney disease, dialysis, end-of-life, race, ethnicity, disparity

End-of-life care is an increasingly prominent consideration, especially in situations where death appears imminent and quality of life is poor. Research and commentary on end-of-life issues have accelerated rapidly. For example, a PubMed search in March of 2018 with the term “end-of-life” revealed that annual citation rates increased over one hundred–fold between 1990 and 2017, from 19 to 2243.1 Unexplained race-based disparities have long been a feature of the United States dialysis population, with black patients experiencing higher incidence rates of ESKD treated with RRT, longer survival, and lower transplantation rates then age-matched, white counterparts.2 Given its emerging importance, it is surprising that examination of race- and ethnicity-associated disparities in end-of-life care in patients with ESKD has largely been restricted to comparisons of white and black patients. This is even more surprising when one considers demographic changes in the general population, and the observation that ESKD rates are meaningfully higher in patients of Hispanic ethnicity than in their white contemporaries.2 Furthermore, it is unknown whether potential disparities differ by mode of health insurance and regional income inequalities. Given these knowledge gaps, we performed a retrospective national study to determine whether end-of-life care in United States dialysis exhibits disparities across multiple races and ethnicities.

Methods

Objectives

Among patients dying on maintenance dialysis between January 1, 2000 and June 30, 2014, the objectives of this study were to quantify associations between race-ethnicity and: (1) the composite outcome of a) discontinuation of dialysis and b) death in either a nonhospital or hospice setting, the primary outcome; and (2) individual components of the composite outcome (discontinuation of dialysis, hospice care, death in a nonhospital setting). In addition, we wished to determine whether associations between race-ethnicity and end-of-life care outcomes differed by: (3) mode of health care insurance and (4) income dispersion, as measured by the Gini index.

Subjects and Measurements

We used United States Renal Data System (USRDS) standard analytic files (“saf”) to study patients on maintenance dialysis who died between January 1, 2000 and June 30, 2014. We used the saf.Death file to determine date, cause, and place of death; discontinuation of dialysis; and hospice care. Demographic factors were obtained from the saf.Patients file; mirroring strategies used in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, “Race” and “Hispanic” variables were used to define race-ethnicity; race was selected when ethnicity was non-Hispanic, and ethnicity when the latter was Hispanic.3 The saf.Patients file was also used to determine date of birth, sex, type of kidney disease, and duration of RRT. Last mode of dialysis and dialysis unit characteristics were determined from the saf.Rxhist and saf.Facility files, respectively. The saf.Payhist file was used to determine insurance status. In the majority subgroup (74.6%) with Medicare parts A and B insurance, Medicare hospitalization files (saf.Hosp) and International Classification of Diseases (Ninth Revision) Clinical Modification codes were used to capture the presence of common medical conditions seen in the last 4 weeks of life. The saf.Residenc file was used to determine the state and county of residence at the time of death; linkage by county to census and Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service files allowed us to determine income dispersion (the Gini index) and rural-urban continuum codes, respectively.4,5

Statistical Analyses

We used the chi-squared test and logistic regression, respectively, for comparisons of categoric variables and calculation of odds ratios. Four adjustment strategies were used for estimating race- and ethnicity-related odds ratios for end-of-life care parameters: model 1—no adjustment; model 2—adjustment for age and sex; model 3—model 2 plus adjustment for Gini index of county-level income dispersion, rural-urban continuum code, type of kidney disease, years of RRT, mode of dialysis, prior transplant, type of insurance, and dialysis unit characteristics; model 4 (applied to subgroup with Medicare parts A and B)—model 3 plus adjustment for number of hospitalization-identified illnesses in the last 28 days of life. Adjustment models were repeated in the following subgroups: those with Medicare Parts A and B health insurance, those insured with group health organizations, those with county-level Gini index below the national median, and those with Gini index above the national median. SAS Version 9.4 (Cary, NC) was used for statistical analyses.6

Results

Of the study population, 27.6% were classified as non-Hispanic black, 1.0% as non-Hispanic Native American, 3.2% as non-Hispanic Asian, and 11.7% as Hispanic (Table 1). The primary cause of death was cardiovascular causes in 39.6%, infection in 10.9%, malignancy in 2.8%, and uremia/dialysis withdrawal in 7.4% (Table 1). A total of 63.2% died in hospital, 19.6% at home, and 7.4% in nursing homes; 14.7% received hospice care before death and 24.9% of the study population discontinued dialysis before death, predominantly because of failure to thrive (34.8% of withdrawals) and medical complications (24.9%; Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics at death of patients on dialysis, compared by race-ethnicity (n=1,098,384)

| Characteristic | Subgroup | All | Minority | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No 56.4% | Yes 43.6% | |||||||

| All M 43.6% | AA 27.6% | NA 1.0% | A 3.2% | H 11.7% | ||||

| Place of death | Hospital | 63.2 | 58.5 | 69.2 | 69.8 | 63.1a | 69.1 | 68.3 |

| Home | 19.6 | 21.5 | 17.0 | 16.1 | 22.4 | 17.6 | 18.6 | |

| Nursing home | 7.4 | 8.8 | 5.5 | 5.9 | 6.3 | 5.3 | 4.8 | |

| Other | 9.9 | 11.1 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 8.2 | 8.0 | 8.3 | |

| Hospice | 14.7 | 18.1 | 10.3 | 9.5 | 11.1 | 10.6 | 12.1 | |

| Hospice location | Nonhospital, nonhome | 36.6 | 37.2 | 35.1 | 37.7 | 29.3 | 32.7 | 31.2 |

| Hospital | 29.2 | 27.1 | 34.2 | 36.9 | 29.7 | 33.9 | 29.8 | |

| Home | 34.2 | 35.7 | 30.7 | 25.5 | 41.0b | 33.4 | 39.0 | |

| Dialysis discontinuation | 24.9 | 31.2 | 16.7 | 15.3 | 23.3 | 18.4 | 18.8 | |

| Reason discontinuedc | Dialysis access failurec | 1.1 | 0.9d | 1.5d | 1.8a | 1.4a | 1.3a | 1.2 |

| Failure to thrivec | 34.8 | 36.2 | 31.5 | 32.3 | 35.3a | 34.3 | 28.8 | |

| Acute medical complicationc | 24.9 | 24.3 | 26.5 | 26.4 | 32.5 | 26.5 | 26.0 | |

| Otherc | 39.1 | 38.6 | 40.5 | 39.6 | 30.8 | 37.9 | 44.1 | |

| Era | 2000–2006 | 46.7 | 47.0 | 46.5 | 48.0 | 48.3d | 43.2 | 43.6 |

| 2007–2014 | 53.3 | 53.0 | 53.5 | 52.0 | 51.7d | 56.8 | 56.4 | |

| Age, yr | 0–39 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 4.5 | 2.1 | 3.4 |

| 40–64 | 31.8 | 25.7 | 39.6 | 41.9 | 46.1 | 27.9 | 36.9 | |

| 65–70 | 42.3 | 43.9 | 40.2 | 38.5 | 40.3 | 43.8 | 43.3 | |

| ≥80 | 22.9 | 28.4 | 15.8 | 14.6 | 9.1 | 26.2 | 16.4 | |

| Female sex | 45.7 | 42.4 | 49.9 | 51.8 | 53.2 | 47.3 | 46.1d | |

| Region | Northeast | 18.6 | 21.7 | 14.6 | 15.9 | 3.8 | 12.8 | 12.5 |

| Midwest | 22.1 | 27.2 | 15.3 | 18.8 | 20.5 | 7.5 | 7.7 | |

| South | 40.7 | 34.6 | 48.9 | 57.6 | 26.6 | 12.6 | 39.1 | |

| West | 18.5 | 16.5 | 21.2 | 7.7 | 49.1 | 67.1 | 40.8 | |

| County type | Metro, ≥1 million | 52.4 | 46.2 | 60.7 | 60.4 | 19.9 | 71.0 | 62.5 |

| Metro, 0.25–0.99 million | 19.6 | 20.4 | 18.5 | 17.4 | 15.1 | 20.7a | 21.1 | |

| Metro, <0.25 million | 9.9 | 11.5 | 7.8 | 8.3 | 11.4 | 2.9 | 7.6 | |

| Nonmetro | 18.1 | 21.9 | 13.0 | 13.9 | 53.6 | 5.3 | 8.7 | |

| County Gini index | ≤0.430 | 26.0 | 34.3 | 15.1 | 14.7 | 30.3 | 24.0 | 12.1 |

| 0.431–0.453 | 24.9 | 28.2 | 20.5 | 19.4 | 37.1 | 25.5d | 20.4 | |

| 0.454–0.481 | 24.6 | 23.2 | 26.5 | 27.9 | 20.1 | 22.0 | 24.9a | |

| >0.481 | 24.5 | 14.3 | 37.9 | 38.0 | 12.5 | 28.5 | 42.5 | |

| Cause of ESKD | Diabetes | 46.9 | 43.0 | 52.0 | 44.9 | 74.7 | 55.3 | 65.9 |

| Hypertension | 28.7 | 28.3 | 29.2 | 35.4 | 9.5 | 25.0 | 17.8 | |

| GN | 8.2 | 8.8 | 7.4 | 7.7 | 7.6b | 9.1 | 6.2 | |

| Cystic disease | 1.6 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Other | 14.6 | 17.8 | 10.5 | 11.2 | 7.5 | 9.6 | 9.2 | |

| RRT, yr | <1 | 29.1 | 33.5 | 23.5 | 23.2 | 18.6 | 23.3 | 24.6 |

| 1–2.9 | 27.7 | 29.5 | 25.3 | 24.5 | 25.7 | 27.2b | 26.9 | |

| 3–4.9 | 17.5 | 16.8 | 18.3 | 17.7 | 19.6 | 19.4 | 19.4 | |

| ≥5 | 25.7 | 20.2 | 32.8 | 34.6 | 36.1 | 30.1 | 29.1 | |

| Type of dialysis | Center hemodialysis | 92.4 | 91.0 | 94.3 | 94.7 | 93.6 | 92.4a | 94.1 |

| Home hemodialysis | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.3a | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.9 | |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 6.2 | 7.6 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 5.8a | 6.7 | 5.0 | |

| Prior transplant | 6.2 | 6.5 | 5.8 | 6.0 | 6.7b | 5.2 | 5.3 | |

| For-profit dialysis unit | 79.5 | 77.4 | 82.3 | 81.7 | 67.9 | 76.4 | 86.8 | |

| Dialysis unit affiliation | Hospital-based | 11.4 | 13.1 | 9.3 | 9.3 | 18.6 | 12.9 | 7.4 |

| Independent | 18.6 | 18.7b | 18.5b | 17.0 | 15.9 | 23.3 | 20.9 | |

| Chain, 2–99 units | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.5 | 4.1 | 1.9 | 8.9 | 4.5 | |

| Chain, ≥100 units | 65.7 | 64.1 | 67.7 | 69.7 | 63.5 | 55.0 | 67.2 | |

| Insurance | Medicare parts A and B | 74.6 | 76.4 | 72.2 | 75.3 | 78.0 | 60.7 | 67.8 |

| Medicare 1°, other | 2.0 | 1.3 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 4.2 | 7.8 | 3.4 | |

| Medicare 2°, EGHP | 3.2 | 3.8 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 1.9 | |

| Medicare 2°, other | 0.9 | 0.9d | 0.9d | 1.0 | 0.8a | 0.4 | 0.7 | |

| Health maintenance organization | 11.3 | 12.1 | 10.3 | 8.3 | 2.6 | 15.5 | 14.3 | |

| 90-d wait for Medicare | 0.2 | 0.2d | 0.2d | 0.2d | 0.1a | 0.2a | 0.2a | |

| Other | 7.8 | 5.3 | 11.1 | 10.6 | 11.9 | 12.5 | 11.6 | |

| Conditions, last 28 d | Myocardial infarction | 6.9 | 6.9b | 7.0b | 6.5 | 6.8a | 9.5 | 7.8 |

| Cardiac failure | 24.6 | 26.5 | 22.0 | 21.6 | 18.0 | 22.2 | 23.3 | |

| Stroke | 5.0 | 4.4 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 4.8a | 6.6 | 5.8 | |

| Malignancy | 14.5 | 14.9 | 14.0 | 14.4a | 12.7 | 13.2 | 13.1 | |

| Pneumonia | 12.0 | 12a | 12.0a | 11.5 | 12.1a | 14.0 | 13.0 | |

| Septicemia | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.6b | 0.4a | 0.4d | |

| Number of conditions | 0 | 54.3 | 53.6 | 55.3 | 55.7 | 59.6 | 53.7a | 54.3a |

| 1 | 30.6 | 30.5b | 30.7b | 30.9d | 27.9 | 30.0b | 30.7a | |

| ≥2 | 15.1 | 15.9 | 14.0 | 13.5 | 12.5 | 16.4 | 15.0a | |

| Cause of death | Cardiovascular | 39.6 | 38.7 | 40.7 | 40.5 | 36.7 | 44.1 | 40.8 |

| Infection | 10.9 | 9.9 | 12.3 | 11.9 | 13.0 | 11.5 | 13.4 | |

| Malignancy | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.8a | 2.0 | 2.4 | 2.1 | |

| Withdrawal of dialysis | 7.4 | 9.7 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 7.0b | 5.4 | 5.5 | |

| Other | 39.3 | 38.8 | 39.9 | 40.9 | 41.3 | 36.5 | 38.3 | |

Parameter estimates are column percentages. P values <0.001 (versus non-Hispanic white) for all comparisons by race/ethnicity, unless otherwise indicated. Northeast (states): Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont; Midwest: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin; South: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia; West: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. Missing data ≥0.1%: race-ethnicity, 0.2%; county type, 1.6%; dialysis chain affiliation, 1.4%. “Conditions” refer to patients with Medicare parts A and B and hospitalizations containing the following International Classification of Disease Clinical Modification–9 codes in the last 28 d of life: myocardial infarction—410xx (1≤x≤9); cardiac failure—428xx; stroke—434xx; malignancy—140xx to 209xx; pneumonia—480xx to 488xx; septicemia—38xxx. M, Minority; AA, black; NA, Native American, A, Asian; H, Hispanic; EGHP, employer group health plan.

NS, P value ≥0.05.

0.01≤P value <0.05.

Column percentages for reason for withdrawal of dialysis have the subgroup who withdrew from dialysis as denominator.

0.001≤P value <0.01.

The primary outcome—a composite of (1) discontinuation of dialysis and (2) death in a nonhospital or hospice setting—was less likely in patients from minority groups (10.9%) than in the white population (22.6%, P value <0.001; Table 2). Corresponding values for dialysis discontinuation, hospice, and nonhospital death were 16.7% versus 31.2%, 10.3% versus 18.1%, and 34.4% versus 46.4%, respectively (P value <0.001 for each comparison; Table 2). Within individual minority groups, primary outcome estimates were arrayed as follows: non-Hispanic black (9.8%) <non-Hispanic Asian (11.2%) <Hispanic (13.0%) <non-Hispanic Native American (14.2%); this pattern was repeated for each component of the primary outcome, with the exception of hospice care, where the pattern was non-Hispanic black (9.5%) <non-Hispanic Asian (10.6%) <non-Hispanic Native American (11.1%) <Hispanic (12.1%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Unadjusted associations of primary outcome (withdrawal of dialysis and death in either a nonhospital or hospice setting), and of component outcomes in patients on dialysis dying between 2000 and 2014 (n=1,098,384)

| Characteristic | Subgroup | Primary Outcome (17.5%) | Dialysis Discontinuation (24.9%) | Hospice (14.7%) | Nonhospital (36.8%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minority | No | 22.6 | 31.2 | 18.1 | 46.4 |

| Yes | 10.9 | 16.7 | 10.3 | 34.4 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 9.8 | 15.3 | 9.5 | 33.7 | |

| Non-Hispanic Native American | 14.2 | 23.3 | 11.1 | 40.2a | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 11.2 | 18.4 | 10.6 | 34.5 | |

| Hispanic | 13.0 | 18.8 | 12.1 | 35.3 | |

| Era | 2000–2006 | 13.5 | 23.1 | 5.9 | 35.8 |

| 2007–2014 | 20.9 | 26.5 | 22.4 | 45.8 | |

| Age, yr | 0–39 | 5.6 | 11.6 | 5.3 | 32.3 |

| 40–64 | 10.1 | 16.4 | 9.6 | 36.3 | |

| 65–70 | 18.3 | 26.2 | 15.2 | 41.1b | |

| ≥80 | 27.7 | 35.9 | 22.0 | 49.2 | |

| Sex | Male | 16.6 | 23.4 | 14.5 | 42.2 |

| Female | 18.5 | 26.7 | 14.9 | 39.9 | |

| Region | Northeast | 16.3 | 24.6c | 12.4 | 38.0 |

| Midwest | 21.3 | 28.7 | 17.2 | 46.5 | |

| South | 15.8 | 23.1 | 14.4 | 39.2 | |

| West | 18.9 | 26.1 | 15.7 | 43.4 | |

| County type | Metro, ≥1 million | 15.7 | 22.1 | 14.2 | 39.3 |

| Metro, 0.25–0.99 million | 20.0 | 28.5 | 16.6 | 43.5 | |

| Metro, <0.25 million | 20.9 | 30.4 | 16.1 | 44.0 | |

| Nonmetro | 20.1 | 28.6 | 15.6 | 44.6 | |

| County Gini index | ≤0.430 | 22.0 | 30.4 | 17.4 | 45.9 |

| 0.431–0.453 | 19.6 | 27.7 | 16.3 | 43.3 | |

| 0.454–0.481 | 17.9 | 25.6 | 15.3 | 41.5 | |

| >0.481 | 10.9 | 16.2 | 10.4 | 34.5 | |

| Cause of ESKD | Diabetes | 15.9 | 23.1 | 13.3 | 40.3 |

| Hypertension | 18.5 | 25.6 | 15.6 | 41.5 | |

| GN | 15.6 | 23.5 | 13.3 | 39.4 | |

| Cystic disease | 16.4 | 24.2a | 14.6b | 42.8 | |

| Other | 21.6 | 30.0 | 18.1 | 43.9 | |

| Years of RRT | <1 | 19.8 | 28.0 | 15.3 | 41.6 |

| 1–2.9 | 18.3 | 25.8 | 15.0 | 42.0 | |

| 3–4.9 | 17.3a | 24.5 | 14.9c | 41.2b | |

| ≥5 | 14.0 | 20.6 | 13.6 | 39.7 | |

| Type of dialysis | Center hemodialysis | 17.7 | 25.2 | 14.8 | 41.1 |

| Home hemodialysis | 12.1 | 16.6 | 12.7 | 39.8c | |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 14.5 | 22.4 | 14.0 | 42.7 | |

| Prior transplant | No | 18.1 | 25.7 | 15.0 | 41.1b |

| Yes | 7.2 | 12.6 | 10.4 | 41.5b | |

| For-profit dialysis unit | No | 18.5 | 27.2 | 14.4 | 42.6 |

| Yes | 17.2 | 24.3 | 14.8 | 40.8 | |

| Dialysis unit affiliation | Hospital-based | 18.3 | 27.7 | 13.1 | 42.6 |

| Independent | 16.0 | 23.2 | 13.2 | 39.4 | |

| Chain, 2–99 units | 19.0 | 25.7 | 18.9 | 43.0 | |

| Chain, ≥100 units | 17.6 | 24.8c | 15.0 | 41.2a | |

| Insurance | Medicare parts A and B | 17.8 | 25.5 | 14.5 | 41.3 |

| Medicare 1°, other | 12.5 | 18.7 | 11.4 | 36.7 | |

| Medicare 2°, employer group health plan | 12.4 | 19.9 | 11.4 | 38.0 | |

| Medicare 2°, other | 19.3 | 25.2b | 19.4 | 45.6 | |

| Health maintenance organization | 22.1 | 28.8 | 20.1 | 45.9 | |

| 90-day wait for Medicare | 12.6 | 20.8 | 9.9 | 34.4 | |

| Other | 10.4 | 16.6 | 10.0 | 35.1 | |

| Conditions, last 28 d | Myocardial infarction | 9.5 | 18.0 | 8.3 | 20.7 |

| Cardiac failure | 15.8 | 25.3 | 13.1 | 31.5 | |

| Stroke | 16.0 | 28.8 | 13.1 | 26.6 | |

| Malignancy | 19.2 | 29.5b | 16.3 | 35.2 | |

| Pneumonia | 14.6 | 24.8b | 12.7 | 28.4 | |

| Septicemia | 22.8 | 31.8 | 22.2 | 39.1a | |

| Number of conditions | 0 | 19.6 | 25.4 | 15.8 | 50.3 |

| 1 | 15.8 | 25.5 | 12.8 | 30.7 | |

| 2 | 15.7 | 25.8 | 13.6 | 29.8 | |

| Cause of death | Cardiovascular | 8.3 | 12.9 | 7.3 | 37.2 |

| Infection | 9.0 | 19.3 | 8.8 | 17.5 | |

| Malignancy | 33.2 | 42.1 | 34.2 | 59.7 | |

| Uremia/withdrawal of dialysis | 81.9 | 94.9 | 72.2 | 85.5 | |

| Other | 15.7 | 24.1 | 11.5 | 41.9 |

Northeast (states): Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont; Midwest: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin; South: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia; West: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. Parameter estimates are row percentages. P values <0.001 for all comparisons unless otherwise stated. “Conditions” refer to patients with Medicare parts A and B with hospitalizations containing the following International Classification of Disease Clinical Modification–9 codes in the last 28 d of life: myocardial infarction—410xx (1≤x≤9); cardiac failure—428xx; stroke—434xx; malignancy—140xx to 209xx; pneumonia—480xx to 488xx; septicemia—38xxx.

0.01≤P value <0.05.

NS, P value ≥0.05.

0.001≤P value <0.01.

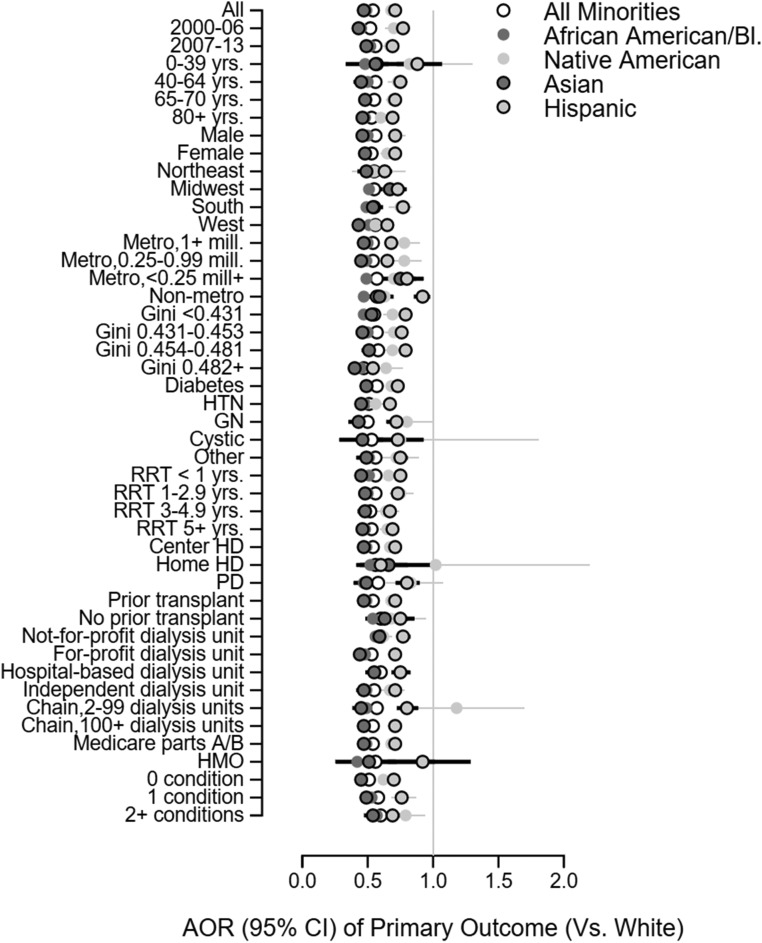

When adjustment was made for age, sex, era, Gini index of county-level income dispersion, rural-urban continuum code, type of kidney disease, years of RRT, mode of dialysis, prior transplant, type of insurance, and dialysis unit characteristics (model 3), the likelihood of the composite primary outcome was lower among patients from any minority group (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] versus white, 0.55; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.55 to 0.56; P value <0.001; Table 3); within individual minority groups, model 3 AOR values (versus white, P value <0.001 for each) were similarly low for non-Hispanic Asian (AOR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.48 to 0.45) and non-Hispanic black (AOR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.47 to 0.49) subgroups and higher, although <1, for non-Hispanic Native American (AOR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.68 to 0.76) and Hispanic (AOR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.72 to 0.74) subgroups (Table 3). Model 3 minority-associated AORs for the primary outcome were <1 (P value <0.001) in all subgroups examined (Figure 1). Findings were similar when outcome models were repeated in the subgroups defined by type of health insurance (Table 4) and in subgroups defined by median county-level Gini index of income dispersion (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 3.

Odds ratios of primary outcome (withdrawal of dialysis and death in either a nonhospital or hospice setting), and of component outcomes, according to minority status in patients on dialysis dying between 2000 and 2014 (n=1,098,384)

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome (17.5%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Minority | 0.42 (0.41 to 0.42) | 0.48 (0.47 to 0.48) | 0.55 (0.55 to 0.56) | 0.54 (0.54 to 0.55) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.37 (0.37 to 0.38) | 0.44 (0.43 to 0.44) | 0.49 (0.49 to 0.50) | 0.49 (0.48 to 0.50) |

| Non-Hispanic Native American | 0.57 (0.54 to 0.60) | 0.72 (0.68 to 0.76) | 0.70 (0.67 to 0.74) | 0.68 (0.64 to 0.72) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.43 (0.42 to 0.45) | 0.42 (0.41 to 0.44) | 0.49 (0.47 to 0.51) | 0.47 (0.45 to 0.49) |

| Hispanic | 0.51 (0.50 to 0.52) | 0.56 (0.55 to 0.57) | 0.73 (0.71 to 0.74) | 0.71 (0.70 to 0.73) |

| Dialysis discontinuation (24.9%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Minority | 0.44 (0.44 to 0.45) | 0.50 (0.49 to 0.50) | 0.58 (0.57 to 0.58) | 0.57 (0.56 to 0.57) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.40 (0.39 to 0.40) | 0.46 (0.45 to 0.46) | 0.52 (0.51 to 0.52) | 0.51 (0.50 to 0.52) |

| Non-Hispanic Native American | 0.67 (0.64 to 0.7) | 0.81 (0.78 to 0.85) | 0.78 (0.74 to 0.81) | 0.75 (0.72 to 0.79) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.50 (0.48 to 0.51) | 0.50 (0.48 to 0.51) | 0.57 (0.56 to 0.59) | 0.55 (0.53 to 0.57) |

| Hispanic | 0.51 (0.5 to 0.52) | 0.56 (0.55 to 0.57) | 0.72 (0.71 to 0.74) | 0.71 (0.70 to 0.73) |

| Hospice (14.7%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Minority | 0.52 (0.52 to 0.53) | 0.57 (0.56 to 0.57) | 0.63 (0.62 to 0.64) | 0.62 (0.62 to 0.63) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.48 (0.47 to 0.48) | 0.54 (0.53 to 0.54) | 0.58 (0.57 to 0.59) | 0.58 (0.57 to 0.59) |

| Non-Hispanic Native American | 0.56 (0.53 to 0.60) | 0.67 (0.63 to 0.71) | 0.70 (0.66 to 0.75) | 0.68 (0.64 to 0.73) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.54 (0.52 to 0.56) | 0.50 (0.48 to 0.52) | 0.54 (0.52 to 0.56) | 0.54 (0.51 to 0.56) |

| Hispanic | 0.62 (0.61 to 0.64) | 0.64 (0.63 to 0.66) | 0.79 (0.77 to 0.81) | 0.78 (0.76 to 0.79) |

| Nonhospital death (41.1%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Minority | 0.60 (0.60 to 0.61) | 0.64 (0.63 to 0.64) | 0.70 (0.70 to 0.71) | 0.69 (0.68 to 0.69) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.59 (0.58 to 0.59) | 0.63 (0.62 to 0.63) | 0.69 (0.68 to 0.70) | 0.67 (0.66 to 0.68) |

| Non-Hispanic Native American | 0.78 (0.75 to 0.80) | 0.85 (0.82 to 0.88) | 0.84 (0.81 to 0.87) | 0.81 (0.77 to 0.84) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.61 (0.59 to 0.62) | 0.60 (0.58 to 0.61) | 0.65 (0.64 to 0.67) | 0.64 (0.62 to 0.66) |

| Hispanic | 0.63 (0.62 to 0.64) | 0.65 (0.64 to 0.66) | 0.74 (0.73 to 0.75) | 0.73 (0.72 to 0.74) |

Parameter estimates are odds ratios from logistic regression models (with 95% CIs in parentheses). P values versus white <0.001 for all odds ratios. Model 1: no adjustment; model 2: adjustment for age and sex; model 3: model 2 plus adjustment for era, Gini index of county-level income dispersion, rural-urban continuum code, type of kidney disease, years of RRT, mode of dialysis, prior transplant, type of insurance, and dialysis unit characteristics; model 4 (population with Medicare parts A and B, n=818,953): model 3 plus adjustment for number of conditions in the last 28 d of life.

Figure 1.

Subgroup analyses; parameter estimates are odds ratios (with 95% CIs and non-Hispanic white as reference category) from logistic regression models for the primary outcome (withdrawal of dialysis and death in either a nonhospital or hospice setting). Odds ratios for race and ethnicity were similar in all subgroups examined. Ethnicity is non-Hispanic, unless otherwise stated. Model 3 adjustment strategy was used: adjustment for age, sex, era, Gini index of county-level income dispersion, rural-urban continuum code, type of kidney disease, years of RRT, mode of dialysis, prior transplant, type of insurance, and dialysis unit characteristics. “Conditions” refers to patients with Medicare parts A and B with hospitalizations for the following in the last 28 days of life: myocardial infarction, cardiac failure, stroke, malignancy, pneumonia, and septicemia. HD, hemodialysis; HMO, health maintenance organization; HTN, hypertension; mill., million (population); PD, peritoneal dialysis; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

Table 4.

Odds ratios of primary outcome (withdrawal of dialysis and death in either a non-hospital or hospice setting), and of component outcomes, according to minority status in patients on dialysis dying between 2000 and 2014, analyzed separately in subgroups defined by insurance provider

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicare A/B | HMO | Medicare A/B | HMO | Medicare A/B | HMO | Medicare A/B | |

| Primary outcome (Medicare A/B, 17.9% of 818,953/HMO, 22.1% of 124,246) | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Minority | 0.41 (0.41 to 0.42) | 0.48 (0.46 to 0.49) | 0.48 (0.47 to 0.48) | 0.5 (0.49 to 0.52) | 0.56 (0.55 to 0.56) | 0.60 (0.58 to 0.62) | 0.55 (0.55 to 0.56) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.37 (0.37 to 0.38) | 0.42 (0.41 to 0.44) | 0.44 (0.43 to 0.45) | 0.45 (0.43 to 0.47) | 0.50 (0.49 to 0.51) | 0.51 (0.49 to 0.54) | 0.50 (0.49 to 0.51) |

| Non-Hispanic Native American | 0.58 (0.54 to 0.61) | 0.60 (0.45 to 0.81) | 0.71 (0.67 to 0.76) | 0.71 (0.52 to 0.95)a | 0.70 (0.66 to 0.74) | 0.70 (0.51 to 0.95)a | 0.69 (0.65 to 0.74) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.41 (0.40 to 0.43) | 0.49 (0.46 to 0.53) | 0.40 (0.39 to 0.42) | 0.51 (0.47 to 0.55) | 0.47 (0.45 to 0.50) | 0.54 (0.50 to 0.58) | 0.47 (0.45 to 0.5) |

| Hispanic | 0.51 (0.50 to 0.52) | 0.55 (0.53 to 0.57) | 0.57 (0.56 to 0.58) | 0.58 (0.55 to 0.60) | 0.72 (0.7 to 0.74) | 0.78 (0.74 to 0.82) | 0.72 (0.70 to 0.74) |

| Dialysis discontinuation (Medicare A/B, 25.5% of 818,953/HMO, 28.8% of 124,246) | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Minority | 0.44 (0.43 to 0.44) | 0.49 (0.48 to 0.50) | 0.50 (0.49 to 0.50) | 0.52 (0.50 to 0.53) | 0.58 (0.57 to 0.59) | 0.63 (0.61 to 0.64) | 0.58 (0.57 to 0.59) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.40 (0.39 to 0.40) | 0.44 (0.42 to 0.45) | 0.46 (0.45 to 0.47) | 0.46 (0.45 to 0.48) | 0.53 (0.52 to 0.53) | 0.54 (0.52 to 0.56) | 0.52 (0.52 to 0.53) |

| Non-Hispanic Native American | 0.66 (0.63 to 0.69) | 0.67 (0.51 to 0.87)b | 0.80 (0.76 to 0.84) | 0.77 (0.59 to 1.01)c | 0.77 (0.73 to 0.81) | 0.77 (0.59 to 1.00)c | 0.77 (0.73 to 0.81) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.47 (0.45 to 0.49) | 0.59 (0.55 to 0.62) | 0.47 (0.46 to 0.49) | 0.60 (0.56 to 0.64) | 0.55 (0.53 to 0.57) | 0.64 (0.60 to 0.68) | 0.55 (0.53 to 0.57) |

| Hispanic | 0.51 (0.50 to 0.51) | 0.53 (0.51 to 0.56) | 0.57 (0.56 to 0.58) | 0.57 (0.55 to 0.59) | 0.72 (0.70 to 0.73) | 0.78 (0.74 to 0.81) | 0.72 (0.7 to 0.73) |

| Hospice (Medicare A/B, 14.5% of 818,953/HMO, 20.1% of 124,246) | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Minority | 0.52 (0.52 to 0.53) | 0.59 (0.57 to 0.61) | 0.57 (0.56 to 0.58) | 0.59 (0.57 to 0.60) | 0.63 (0.62 to 0.64) | 0.68 (0.66 to 0.70) | 0.63 (0.62 to 0.64) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.48 (0.47 to 0.49) | 0.54 (0.52 to 0.56) | 0.54 (0.53 to 0.55) | 0.54 (0.52 to 0.56) | 0.59 (0.58 to 0.60) | 0.59 (0.57 to 0.62) | 0.59 (0.58 to 0.6) |

| Non-Hispanic Native American | 0.58 (0.54 to 0.62) | 0.86 (0.65 to 1.14)c | 0.67 (0.62 to 0.71) | 0.98 (0.73 to 1.31)c | 0.69 (0.64 to 0.74) | 0.98 (0.73 to 1.33)c | 0.69 (0.64 to 0.74) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.55 (0.52 to 0.57) | 0.55 (0.51 to 0.60) | 0.50 (0.47 to 0.52) | 0.57 (0.53 to 0.62) | 0.54 (0.51 to 0.56) | 0.58 (0.54 to 0.63) | 0.54 (0.51 to 0.56) |

| Hispanic | 0.62 (0.61 to 0.64) | 0.67 (0.64 to 0.70) | 0.66 (0.64 to 0.67) | 0.66 (0.63 to 0.68) | 0.78 (0.76 to 0.80) | 0.88 (0.84 to 0.92) | 0.78 (0.76 to 0.8) |

| Nonhospital death (Medicare A/B, 41.3% of 818,953/HMO, 45.9% of 124,246) | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Minority | 0.60 (0.59 to 0.61) | 0.64 (0.63 to 0.66) | 0.63 (0.63 to 0.64) | 0.65 (0.64 to 0.67) | 0.70 (0.69 to 0.70) | 0.71 (0.69 to 0.73) | 0.68 (0.67 to 0.69) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.58 (0.58 to 0.59) | 0.61 (0.59 to 0.63) | 0.62 (0.62 to 0.63) | 0.63 (0.61 to 0.64) | 0.68 (0.68 to 0.69) | 0.67 (0.65 to 0.69) | 0.67 (0.66 to 0.67) |

| Non-Hispanic Native American | 0.78 (0.75 to 0.82) | 0.68 (0.54 to 0.85)b | 0.85 (0.81 to 0.88) | 0.73 (0.58 to 0.92)b | 0.82 (0.79 to 0.86) | 0.72 (0.57 to 0.92)b | 0.80 (0.77 to 0.84) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.59 (0.58 to 0.61) | 0.66 (0.62 to 0.7) | 0.58 (0.56 to 0.60) | 0.67 (0.64 to 0.71) | 0.64 (0.62 to 0.66) | 0.68 (0.64 to 0.72) | 0.63 (0.61 to 0.65) |

| Hispanic | 0.62 (0.61 to 0.63) | 0.68 (0.65 to 0.7) | 0.65 (0.64 to 0.66) | 0.69 (0.66 to 0.71) | 0.73 (0.72 to 0.74) | 0.81 (0.78 to 0.84) | 0.73 (0.71 to 0.74) |

Parameter estimates are odds ratios from logistic regression models (with 95% CIs in parentheses). P values versus white <0.001 for all odds ratios. Model 1: no adjustment; model 2: adjustment for age and sex; model 3: model 2 plus adjustment for era, Gini index of county-level income dispersion, rural-urban continuum code, type of kidney disease, years of RRT, mode of dialysis, prior transplant, type of insurance, and dialysis unit characteristics; model 4 (population with Medicare parts A and B): model 3 plus adjustment for number of conditions in the last 28 d of life. HMO, health maintenance organization.

XXX.

XXX.

NS.

Table 5.

Odds ratios of primary outcome (withdrawal of dialysis and death in either a nonhospital or hospice setting), and of component outcomes, according to minority status in patients on dialysis dying between 2000 and 2014, analyzed separately in subgroups defined by the median county-level Gini index of 0.43

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.43 | >0.43 | ≤0.43 | >0.43 | ≤0.43 | >0.43 | ≤0.43 | >0.43 | |

| Primary outcome (≤0.43, 14.4% of 528,817/>0.43, 20.8% of 547,979) | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Minority | 0.49 (0.48 to 0.49) | 0.42 (0.42 to 0.43) | 0.55 (0.54 to 0.56) | 0.48 (0.48 to 0.49) | 0.57 (0.56 to 0.58) | 0.55 (0.54 to 0.56) | 0.57 (0.56 to 0.58) | 0.54 (0.53 to 0.55) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.41 (0.40 to 0.42) | 0.39 (0.38 to 0.40) | 0.48 (0.47 to 0.49) | 0.46 (0.45 to 0.47) | 0.50 (0.49 to 0.51) | 0.51 (0.50 to 0.52) | 0.50 (0.48 to 0.51) | 0.50 (0.49 to 0.51) |

| Non-Hispanic Native American | 0.57 (0.53 to 0.61) | 0.56 (0.51 to 0.62) | 0.71 (0.67 to 0.76) | 0.71 (0.64 to 0.79) | 0.72 (0.67 to 0.77) | 0.73 (0.66 to 0.81) | 0.70 (0.65 to 0.76) | 0.69 (0.61 to 0.77) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.48 (0.46 to 0.51) | 0.44 (0.42 to 0.46) | 0.48 (0.46 to 0.50) | 0.42 (0.40 to 0.44) | 0.51 (0.48 to 0.53) | 0.49 (0.46 to 0.52) | 0.50 (0.47 to 0.53) | 0.46 (0.43 to 0.49) |

| Hispanic | 0.66 (0.64 to 0.68) | 0.49 (0.48 to 0.51) | 0.74 (0.72 to 0.76) | 0.54 (0.53 to 0.55) | 0.78 (0.76 to 0.80) | 0.69 (0.67 to 0.71) | 0.78 (0.75 to 0.81) | 0.67 (0.65 to 0.69) |

| Dialysis Discontinuation (≤0.43, 20.9% of 528,817/>0.43, 29.9% of 547,979) | ||||||||

| Minority | 0.51 (0.50 to 0.52) | 0.44 (0.44 to 0.45) | 0.57 (0.57 to 0.58) | 0.50 (0.49 to 0.51) | 0.61 (0.60 to 0.61) | 0.57 (0.56 to 0.58) | 0.60 (0.59 to 0.61) | 0.56 (0.55 to 0.57) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.44 (0.43 to 0.45) | 0.42 (0.41 to 0.42) | 0.50 (0.49 to 0.51) | 0.48 (0.47 to 0.49) | 0.53 (0.52 to 0.54) | 0.53 (0.52 to 0.54) | 0.52 (0.51 to 0.54) | 0.52 (0.51 to 0.53) |

| Non-Hispanic Native American | 0.66 (0.63 to 0.70) | 0.66 (0.60 to 0.71) | 0.80 (0.76 to 0.85) | 0.80 (0.73 to 0.86) | 0.80 (0.76 to 0.85) | 0.80 (0.73 to 0.87) | 0.78 (0.74 to 0.83) | 0.77 (0.7 to 0.85) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.56 (0.54 to 0.58) | 0.49 (0.47 to 0.51) | 0.57 (0.54 to 0.59) | 0.47 (0.45 to 0.50) | 0.60 (0.58 to 0.63) | 0.56 (0.54 to 0.59) | 0.59 (0.56 to 0.62) | 0.52 (0.5 to 0.55) |

| Hispanic | 0.65 (0.64 to 0.67) | 0.49 (0.48 to 0.50) | 0.72 (0.71 to 0.74) | 0.54 (0.53 to 0.55) | 0.78 (0.76 to 0.80) | 0.69 (0.68 to 0.71) | 0.78 (0.76 to 0.81) | 0.67 (0.65 to 0.68) |

| Hospice (≤0.43, 12.9% of 528,817/>0.43, 16.9% of 547,979) | ||||||||

| Minority | 0.59 (0.58 to 0.60) | 0.52 (0.51 to 0.53) | 0.63 (0.62 to 0.64) | 0.56 (0.55 to 0.57) | 0.64 (0.63 to 0.65) | 0.64 (0.62 to 0.65) | 0.64 (0.62 to 0.65) | 0.62 (0.61 to 0.64) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.51 (0.5 to 0.52) | 0.49 (0.48 to 0.50) | 0.56 (0.55 to 0.57) | 0.56 (0.54 to 0.57) | 0.57 (0.55 to 0.58) | 0.60 (0.59 to 0.61) | 0.57 (0.55 to 0.58) | 0.6 (0.58 to 0.61) |

| Non-Hispanic Native American | 0.58 (0.54 to 0.62) | 0.54 (0.49 to 0.61) | 0.67 (0.63 to 0.72) | 0.65 (0.58 to 0.73) | 0.72 (0.67 to 0.78) | 0.69 (0.62 to 0.78) | 0.71 (0.66 to 0.77) | 0.64 (0.56 to 0.73) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.60 (0.57 to 0.63) | 0.54 (0.51 to 0.57) | 0.56 (0.53 to 0.59) | 0.48 (0.46 to 0.51) | 0.56 (0.53 to 0.59) | 0.54 (0.51 to 0.57) | 0.56 (0.52 to 0.59) | 0.53 (0.49 to 0.56) |

| Hispanic | 0.79 (0.77 to 0.81) | 0.59 (0.58 to 0.61) | 0.83 (0.80 to 0.85) | 0.60 (0.58 to 0.62) | 0.84 (0.82 to 0.87) | 0.76 (0.73 to 0.78) | 0.84 (0.81 to 0.87) | 0.73 (0.71 to 0.76) |

| Non-Hospital (≤0.43, 38.0% of 528817/>0.43, 44.6% of 547,979) | ||||||||

| Minority | 0.63 (0.62 to 0.64) | 0.64 (0.63 to 0.64) | 0.66 (0.66 to 0.67) | 0.66 (0.66 to 0.67) | 0.69 (0.68 to 0.70) | 0.71 (0.70 to 0.72) | 0.67 (0.66 to 0.68) | 0.69 (0.68 to 0.70) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.58 (0.58 to 0.59) | 0.63 (0.62 to 0.64) | 0.62 (0.61 to 0.63) | 0.67 (0.66 to 0.68) | 0.65 (0.64 to 0.66) | 0.71 (0.7 to 0.72) | 0.63 (0.62 to 0.65) | 0.69 (0.68 to 0.70) |

| Non-Hispanic Native American | 0.79 (0.76 to 0.83) | 0.73 (0.68 to 0.78) | 0.87 (0.83 to 0.91) | 0.79 (0.74 to 0.85) | 0.86 (0.82 to 0.90) | 0.80 (0.75 to 0.86) | 0.83 (0.78 to 0.87) | 0.77 (0.71 to 0.84) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.61 (0.59 to 0.63) | 0.67 (0.65 to 0.69) | 0.60 (0.58 to 0.62) | 0.65 (0.63 to 0.67) | 0.62 (0.60 to 0.64) | 0.69 (0.67 to 0.72) | 0.61 (0.58 to 0.63) | 0.68 (0.65 to 0.71) |

| Hispanic | 0.74 (0.72 to 0.76) | 0.63 (0.62 to 0.64) | 0.77 (0.75 to 0.78) | 0.65 (0.64 to 0.66) | 0.80 (0.78 to 0.82) | 0.71 (0.70 to 0.72) | 0.78 (0.76 to 0.80) | 0.70 (0.68 to 0.71) |

Parameter estimates are odds ratios from logistic regression models (with 95% CIs in parentheses). P values versus white <0.001 for all odds ratios. Model 1: no adjustment; model 2: adjustment for age and sex; model 3: model 2 plus adjustment for era, Gini index of county-level income dispersion, rural-urban continuum code, type of kidney disease, years of RRT, mode of dialysis, prior transplant, type of insurance, and dialysis unit characteristics; model 4 (population with Medicare parts A/B, n=818,953): model 3 plus adjustment for number of illnesses in the last 28 d of life.

Table 6.

STROBE statement—checklist of items that should be included in reports of observational studies

| Variable | Item No. | Recommendation | Page No. | Relevant Text from Manuscript |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title and abstract | 1 | (1) Indicate the study’s design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract | 3 | Retrospective |

| (2) Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was done and what was found | 3 | Methods and Results sections of abstract | ||

| Introduction | ||||

| Background/rationale | 2 | Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported | 4 | All page 4 |

| Objectives | 3 | State specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses | 5 | Under: Objectives |

| Methods | ||||

| Study design | 4 | Present key elements of study design early in the paper | 4 | Last sentence |

| Setting | 5 | Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, exposure, follow-up, and data collection | ||

| Participants | 6 | (1) Cohort study—Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of selection of participants. Describe methods of follow-up Case-control study—Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of case ascertainment and control selection. Give the rationale for the choice of cases and controls Cross-sectional study—Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of selection of participants | Page 5: “Subjects and Measurements” | |

| (2) Cohort study—For matched studies, give matching criteria and number of exposed and unexposed Case-control study—For matched studies, give matching criteria and the number of controls per case | N/A | |||

| Variables | 7 | Clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers. Give diagnostic criteria, if applicable | Page 5: “Subjects and Measurements” | |

| Data sources/measurement | 8a | For each variable of interest, give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement). Describe comparability of assessment methods if there is more than one group | Page 5: “Subjects and Measurements” | |

| Bias | 9 | Describe any efforts to address potential sources of bias | Statistical adjustments described on page 5. | |

| Study size | 10 | Explain how the study size was arrived at | Full national experience: explicit | |

| Quantitative variables | 11 | Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses. If applicable, describe which groupings were chosen and why | Page 5: “Subjects and Measurements” | |

| Statistical methods | 12 | (1) Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding | Statistical adjustments described on page 5. | |

| (2) Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions | All subgroups of Table 1 were examined | |||

| (3) Explain how missing data were addressed | Very low frequency; no imputation. | |||

| (4) Cohort study—If applicable, explain how loss to follow-up was addressed Case-control study—If applicable, explain how matching of cases and controls was addressed Cross-sectional study—If applicable, describe analytic methods taking account of sampling strategy | N/A | |||

| (5) Describe any sensitivity analyses | None | |||

| Results | ||||

| Participants | 13a | (1) Report numbers of individuals at each stage of study—e.g., numbers potentially eligible, examined for eligibility, confirmed eligible, included in the study, completing follow-up, and analyzed | N/A | |

| (2) Give reasons for nonparticipation at each stage | N/A | |||

| (3) Consider use of a flow diagram | N/A | |||

| Descriptive data | 14a | (1) Give characteristics of study participants (e.g., demographic, clinical, social) and information on exposures and potential confounders | Table 1 | |

| (2) Indicate number of participants with missing data for each variable of interest | Table 1 | |||

| (3) Cohort study—Summarize follow-up time (e.g., average and total amount) | N/A | |||

| Outcome data | 15a | Cohort study—Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures over time | N/A | |

| Case-control study—Report numbers in each exposure category, or summary measures of exposure | N/A | |||

| Cross-sectional study—Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures | Tables 1–3 | |||

| Main results | 16 | (1) Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates and their precision (e.g., 95% CI). Make clear which confounders were adjusted for and why they were included | 95% CI, stated explicitly throughout. | |

| (2) Report category boundaries when continuous variables were categorized | Done | |||

| (3) If relevant, consider translating estimates of relative risk into absolute risk for a meaningful time period | N/A | |||

| Other analyses | 17 | Report other analyses done—e.g., analyses of subgroups and interactions, and sensitivity analyses | Done | |

| Discussion | ||||

| Key results | 18 | Summarize key results with reference to study objectives | 8 | First line of Discussion |

| Limitations | 19 | Discuss limitations of the study, taking into account sources of potential bias or imprecision. Discuss both direction and magnitude of any potential bias | 11 | Second-to-last paragraph of Discussion. |

| Interpretation | 20 | Give a cautious overall interpretation of results considering objectives, limitations, multiplicity of analyses, results from similar studies, and other relevant evidence | Last paragraph of Discussion. | |

| Generalizability | 21 | Discuss the generalizability (external validity) of the study results | This is a full national sample | |

| Other information | ||||

| Funding | 22 | Give the source of funding and the role of the funders for this study and, if applicable, for the original study on which this article is based | Not funded |

An Explanation and Elaboration article discusses each checklist item and gives methodologic background and published examples of transparent reporting. The STROBE checklist is best used in conjunction with this article (freely available on the Web sites of PLoS Medicine at http://www.plosmedicine.org/, Annals of Internal Medicine at http://www.annals.org/, and Epidemiology at http://www.epidem.com/). Information on the STROBE Initiative is available at www.strobe-statement.org. STROBE, STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology; N/A: not available.

Give information separately for cases and controls in case-control studies and, if applicable, for exposed and unexposed groups in cohort and cross-sectional studies.

Discussion

We observed that patients of minority race or ethnicity were less likely to discontinue dialysis, less likely to receive hospice care, and more likely to die in hospital than their non-Hispanic white counterparts. Across the breadth of end-of-life outcomes studied here, patterns were broadly similar for patients of non-Hispanic black and Asian race-ethnicity, and broadly similar for patients of non-Hispanic Native American race-ethnicity and Hispanic ethnicity. These disparities could not be explained by differences in age, demography, local income dispersion, urban-rural configuration, dialysis facility type, mode of insurance coverage, and recent illness profiles, and were evident in a wide range of subgroups.

The proportions of patients on dialysis dying in nonhospital or hospice settings in this study appeared low when compared with populations without ESKD. For example, among Medicare-insured participants in the Health and Retirement Survey who died between 1998 and 2012, the average age at death was 83 years and 29.3% died in hospital (versus 63.2% in patients on dialysis in our study) and 37.3% received hospice care (versus 14.7%).7 In nondialysis settings racial and ethnic disparities have also been described in many domains of end-of-life care, including access to palliative care, symptom alleviation, and communication.8–10 Compared with white individuals, those from minority populations have a greater likelihood of death in a hospital setting, and those of black race or Hispanic ethnicity are at higher risks of being hospitalized and receiving intensive care in the last 6 months of life.11 Several studies also suggest that individuals from black, Hispanic, and Asian minority populations are less well informed about advance directives and less likely to complete them.12–14 Other studies have shown lower rates of hospice use for older adults from minority populations, across a wide variety of care settings, major diagnoses, and geographic regions.15–19

Few studies have specifically focused on the nexus of race, ethnicity, dialysis withdrawal, hospice care, and death outside of conventional hospital settings. This being said, unexplained disparities have been observed in related domains of care. For example, one study reported that Hispanic patients on dialysis were more likely to undergo intensive medical procedures such as ventilation, tracheostomy, feeding enterostomy, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the last 6 months of life.20 Other studies comparing black to white patients showed that in-hospital death, dialysis discontinuation, and hospice referral differed substantially between the two racial populations examined, as well as across regions of the United States.21–23

Our study differs from these informative studies in a number of ways. One difference from preexisting research in this area is that, because the analysis relied on the Death Notification Form, as opposed to Medicare claims, we were able to describe patterns of end-of-life care for groups without Medicare Parts A and B coverage. In this regard, it was notable that adjusted race-and-ethnicity–associated odds ratios for our primary outcome were similar in the subgroups with insurance provided by Medicare Parts A and B and health maintenance organizations. Another potentially novel aspect of this study was the examination of racial-ethnic disparities within regions of different income dispersion. Regarding regional income dispersion, it was notable that adjusted race-and-ethnicity–associated odds ratios for our primary outcome were similar in all levels examined.

In particular, having focused on several minority groups, we found that non-Hispanic white patients on dialysis were the outlier with regard to end-of-life care. Although our study cannot accurately assess the role of patient-related and non–patient-related factors in our findings, the observation that end-of-life care differed between nonminority and the combined minority population, as well as between individual minority groups, tempts one to speculate that the causes of the disparities seen in this study may be multifaceted; for example, if end-of-life care was entirely decided by an entity other than the individual patient, and this entity uniformly treated individuals from the majority population in one way, and individuals from minority populations in another way, one would not expect to see differences between minority groups.

This study has limitations, including its retrospective, registry-based design and the use of reimbursement claims to define comorbidity close to death. Another limitation of our study is the fact that the variables contained in the USRDS Death Notification Form file have not been formally validated. Confronted with substantial racial and ethnic biases at the level of health delivery systems, careful, prospective confirmatory studies are needed to characterize attitudes and belief systems regarding end-of-life issues, both among health care recipients and health care providers.

Despite its limitations, our study may have useful features. It is nationally representative and the large sample sizes help to generate precise association estimates, within the overall population and within multiple subgroups. Given that ongoing illness is likely to influence end-of-life care, the ability to capture comorbid illness present may be advantageous, because it tends to counter the hypothesis that racial and ethnic disparities in end-of-life care are explicable by differences in illness profiles.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

R.N.F.: (1) Substantial contributions to conception and design. Substantial contributions to acquisition of data. Substantial contributions to analysis and interpretation of data. (2) Substantial contributions to drafting the article. Substantial contributions to revising it critically for important intellectual content. (3) Final approval of the version to be published. (4) Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work. D.J.S.: (1) Substantial contributions to conception and design. Substantial contributions to acquisition of data. Substantial contributions to analysis and interpretation of data. (2) Substantial contributions to drafting the article. Substantial contributions to revising it critically for important intellectual content. (3) Final approval of the version to be published. (4) Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work. P.D.: (1) Substantial contributions to conception and design. (2) Substantial contributions to revising it critically for important intellectual content. (3) Final approval of the version to be published. (4) Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work. A.I.: (1) Substantial contributions to analysis and interpretation of data. (2) Substantial contributions to revising it critically for important intellectual content. (3) Final approval of the version to be published. (4) Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work. S.R.: (1) Substantial contributions to conception and design. (2) Substantial contributions to drafting the article. Substantial contributions to revising it critically for important intellectual content. (3) Final approval of the version to be published. (4) Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

References

- 1.National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine: PubMed home page. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/. Accessed April 3, 2018

- 2.United States Renal Data System: Annual Data Report 2017. Available at: https://www.usrds.org/adr.aspx. Accessed April 3, 2018

- 3.National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm. Accessed April 3, 2018

- 4.United States Census Bureau: American Fact Finder. Available at: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml. Accessed April 3, 2018

- 5.United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service: Data Products. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products. Accessed April 3, 2018

- 6.SAS Institute: SAS 9.4 Software. Available at: https://www.sas.com/en_us/software/sas9.html. Accessed April 3, 2018

- 7.Byhoff E, Harris JA, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ: Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life medicare expenditures. J Am Geriatr Soc 64: 1789–1797, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson KO, Green CR, Payne R: Racial and ethnic disparities in pain: Causes and consequences of unequal care. J Pain 10: 1187–1204, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welch LC, Teno JM, Mor V: End-of-life care in black and white: Race matters for medical care of dying patients and their families. J Am Geriatr Soc 53: 1145–1153, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mack JW, Paulk ME, Viswanath K, Prigerson HG: Racial disparities in the outcomes of communication on medical care received near death. Arch Intern Med 170: 1533–1540, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Center for Health Statistics (US): Health, United States, 2010: With special feature on death and dying. Hyattsville, MD, National Center for Health Statistics (US), 2011. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK54381/. Accessed April 2, 2018 [PubMed]

- 12.Kwak J, Haley WE: Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups. Gerontologist 45: 634–641, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwak J, Salmon JR: Attitudes and preferences of Korean-American older adults and caregivers on end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc 55: 1867–1872, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelley AS, Wenger NS, Sarkisian CA: Opiniones: End-of-life care preferences and planning of older Latinos. J Am Geriatr Soc 58: 1109–1116, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greiner KA, Perera S, Ahluwalia JS: Hospice usage by minorities in the last year of life: Results from the National Mortality Followback Survey. J Am Geriatr Soc 51: 970–978, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ngo-Metzger Q, Phillips RS, McCarthy EP: Ethnic disparities in hospice use among Asian-American and Pacific Islander patients dying with cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc 56: 139–144, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lackan NA, Ostir GV, Freeman JL, Kuo Y-F, Zhang DD, Goodwin JS: Hospice use by Hispanic and non-Hispanic white cancer decedents. Health Serv Res 39: 969–983, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lepore MJ, Miller SC, Gozalo P: Hospice use among urban Black and White U.S. nursing home decedents in 2006. Gerontologist 51: 251–260, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Givens JL, Tjia J, Zhou C, Emanuel E, Ash AS: Racial and ethnic differences in hospice use among patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med 170: 427–432, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eneanya ND, Hailpern SM, O’Hare AM, Kurella Tamura M, Katz R, Kreuter W, et al.: Trends in receipt of intensive procedures at the end of life among patients treated with maintenance dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 69: 60–68, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gessert CE, Haller IV, Johnson BP: Regional variation in care at the end of life: Discontinuation of dialysis. BMC Geriatr 13: 39, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Hare AM, Rodriguez RA, Hailpern SM, Larson EB, Kurella Tamura M: Regional variation in health care intensity and treatment practices for end-stage renal disease in older adults. JAMA 304: 180–186, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas BA, Rodriguez RA, Boyko EJ, Robinson-Cohen C, Fitzpatrick AL, O’Hare AM: Geographic variation in black-white differences in end-of-life care for patients with ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1171–1178, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.