Abstract

Activation of protein kinase C (PKC) by phorbol ester facilitates hormonal secretion and transmitter release, and phorbol ester-induced synaptic potentiation (PESP) is a model for presynaptic facilitation. A variety of PKC isoforms are expressed in the central nervous system, but the isoform involved in the PESP has not been identified. To address this question, we have applied immunocytochemical and electrophysiological techniques to the calyx of Held synapse in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB) of rat auditory brainstem. Western blot analysis indicated that both the Ca2+-dependent “conventional” PKC and Ca2+-independent “novel” PKC isoforms are expressed in the MNTB. Denervation of afferent fibers followed by organotypic culture, however, selectively decreased “novel” ɛPKC isoform expressed in this region. The afferent calyx terminal was clearly labeled with the ɛPKC immunofluorescence. On stimulation with phorbol ester, presynaptic ɛPKC underwent autophosphorylation and unidirectional translocation toward the synaptic side. Chelating presynaptic Ca2+, by using membrane permeable EGTA analogue or high concentration of EGTA directly loaded into calyceal terminals, had only a minor attenuating effect on the PESP. We conclude that the Ca2+-independent ɛPKC isoform mediates the PESP at this mammalian central nervous system synapse.

Protein kinase C (PKC) comprises a family of serine/threonine protein kinases that are widely distributed in a variety of tissues with high concentrations in neuronal tissues. The PKC isozymes are classified into the “conventional” PKC (cPKC; α, β1, β2, and γ), the “novel” PKC (nPKC; δ, ɛ, η, and θ), and the “atypical” PKC (aPKC; ζ and ι/λ) subspecies (1). These different isoforms exhibit distinct tissue distributions, suggesting specific roles in various cellular functions (2). On activation, in secretory cells, PKC translocates from cytosol to cell membrane (3–6), possibly to the proximity of its target. At synapses, many proteins involved in synaptic transmission are possible targets of PKC (2). Phorbol ester enhances transmitter release (7, 8), and this effect is thought to be mediated by presynaptic PKC acting on the release machinery (9, 10). The specific target of PKC, however, has not been identified. Also, there is no direct evidence that phorbol ester activates PKC in the presynaptic terminal. PKC is thought to play regulatory roles in the induction mechanism of long-term synaptic modulation (11–14), thereby possibly involved in memory formation (15). Thus, it is of particular importance to clarify molecular mechanisms underlying the presynaptic facilitatory effect of phorbol ester.

Among PKC isozymes, α, β, γ (cPKC) and δ, ɛ (novel PKC) subspecies are expressed in the central nervous system (2), but it has not been determined which isozyme is involved in the phorbol ester-induced synaptic potentiation (PESP). The calyx of Held is a glutamatergic nerve terminal of globular bushy cells in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus (aVCN) innervating the principal cells in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB) in mammalian brainstem (16). Because of its large size, intraterminal localization of presynaptic proteins can be resolved under a laser confocal microscope (17, 18), and direct patch-clamp recordings can be made from the terminal viewed in thin slices (19–21). At this synapse, phorbol ester presynaptically potentiates excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) without affecting presynaptic Ca2+ or K+ currents (10). Taking advantage of this large terminal, we examined which PKC isozymes are involved in the PESP, and whether activated PKC translocates to the cell membrane in the nerve terminal, as it does in secretory cells.

Methods

All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Physiological Society of Japan.

Immunocytochemistry.

Wistar rats (13–15 days old) were anesthetized with Nembutal and transcardially perfused with a fixative (4% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% picric acid in 0.1 M sodium phosphate, pH 7.4). The phorbol ester 4β-PDBu (1 μM) or its inactive analogue 4α-PDBu (1 μM) was dissolved in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF, see below for composition) and applied through transcardial perfusion for 3 min before the fixative. After fixation, rats were decapitated, and a tissue block of the brainstem including the MNTB region was removed for postfixation for 1–2 days at 4°C. The fixed tissue was cryoprotected at 4°C in 0.1 M sodium phosphate with sucrose of graded concentrations: in 4% sucrose for 30 min, 10% for 2 h, 15% for 2 h, and 20% for overnight. Transverse slices (25 μm in thickness) were cut by using a cryostat (CM3050, Leica, Nussloch Germany) at −21°C. The sections were then processed for immunocytochemistry as follows: (i) blocking and permeabilization in PBS containing 4% skim milk and 0.3% (wt/vol) Triton X-100 for 5 h, (ii) application of primary antibodies in PBS containing 0.5% (wt/vol) BSA and 0.05% Triton X-100 for 2 days at 4°C, (iii) application of secondary antibodies in the same buffer as primary antibodies for overnight at 4°C, and (iv) mounting with ProLong antifade kit (Molecular Probes). ɛPKC was visualized with rabbit polyclonal anti-ɛPKC and anti-autophosphorylated ɛPKC by using the conventional avidin-biotin horseradish peroxidase complex method (ABC elite, Vector Laboratories) followed by tyramide-FITC amplification (NEN). F-actin was visualized with phalloidin conjugated with Alexa fluor 568 (Molecular Probes). The primary antibodies were mouse monoclonal anti-syntaxin (Sigma, diluted 1:100), rabbit polyclonal anti-ɛPKC (Sigma, diluted 1:5000), and rabbit polyclonal anti-autophosphorylated ɛPKC (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid NY, diluted 1:100). The secondary antibodies were anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa fluor 568 (Molecular Probes, diluted 1:200) and anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with biotin (Vector Laboratories, diluted 1:500). Stained sections were viewed with a ×100 oil-immersion objective (numerical aperture 1.35) by using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Fluoview FV300, Olympus Optical, Tokyo Japan). Emission wavelengths are 510–530 nm (for green) and >610 nm (for red). All of the immunocytochemical procedures were carried at room temperature (22–27°C) unless otherwise noted.

Confocal Fluorescence Image Analysis.

To quantify the translocation of ɛPKC induced by phorbol ester application, fluorescence intensities for ɛPKC immunoreactivity and F-actin (phalloidin staining) were measured along the radial axis across the synapse. The position of highest F-actin fluorescence intensity was first determined, and the fluorescence intensities of F-actin and ɛPKC were measured at various distances from this point. To quantify the phosphorylated ɛPKC, total immunofluorescence intensity for phosphorylated ɛPKC at a confocal plane in a calyceal nerve terminal was measured. For all fluorescence quantifications, background fluorescence was subtracted. The significance of difference was evaluated by Student's unpaired t test, with 0.05 as the level of significance.

Denervation Experiments.

Wistar rats (13 days old) were decapitated under halothane anesthesia. After isolating a brainstem block, transverse slices including the MNTB region (400 μm thick) were cut by using a tissue slicer (DTK 1000; Dosaka, Kyoto, Japan). To denervate afferent inputs into MNTB neurons, the aVCN regions on both sides were removed manually with a razor blade under a dissecting microscope, and slices were kept in organotypic culture as described previously (22). However, even without dissecting the aVCN, calyces of Held appeared to degenerate during culture, because no EPSC could be evoked in MNTB neurons (Y. Kajikawa, M. Okada, and T.T., unpublished observation). For Western blotting, tissues including MNTB regions were trimmed under a dissecting microscope by using a razor blade from slices kept for 7 days in culture or from acute slices for control. The tissue samples were sonicated, and their protein concentrations were determined by the DC protein assay (Bio-Rad). Samples containing 10 μg protein were separated by 4% to 20% gradient SDS/PAGE and electrophoretically transferred onto poly(vinylidene difluoride) (PVDF) membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore). After blocking with TPBS (PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20) containing 5% skim milk, PVDF membranes were incubated with primary antibodies in TPBS overnight at 4°C. The antibodies used were mouse monoclonal anti-synapsin (Chemicon, diluted 1:1000), mouse monoclonal anti-αPKC (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY, diluted 1:1000), mouse monoclonal anti-βPKC (Transduction Laboratories, diluted 1:250), mouse monoclonal anti-δPKC (Transduction Laboratories, diluted 1:500), mouse monoclonal anti-γPKC (Transduction Laboratories, diluted 1:5000), rabbit polyclonal anti-ɛPKC (Sigma, diluted 1:5000), mouse monoclonal anti-Munc13 (Synaptic Systems, Göttingen Germany, diluted 1:500). Blotted membranes were visualized with peroxidase ABC elite kit (Vector Laboratories) followed by POD immunostain set (Wako, Osaka).

Electrophysiological Recordings.

Transverse slices of the superior olivary complex were prepared from Wistar rats (13–15 days old) killed by decapitation under halothane anesthesia. The MNTB neurons and calyces were viewed with a ×60 water immersion lens (Olympus Optical) attached to an upright microscope (Axioskop, Zeiss). Each slice was superfused with aCSF containing 120 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 26 mM NaHCO3, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, 0.5 mM myo-inositol, 2 mM sodium pyruvate, and 0.5 mM ascorbic acid (pH 7.4) with 5% CO2 and 95% O2. The aCSF contained routinely bicuculline methiodide (10 μM) and strychnine hydrochloride (0.5 μM) to block spontaneous inhibitory synaptic currents. Effect of phorbol ester on EPSCs was tested in the aCSF containing 1 mM Ca2+ and 2 mM Mg2+. For simultaneous pre- and postsynaptic whole-cell recordings, presynaptic pipettes were filled with the solution containing 97.5 mM potassium gluconate, 32.5 mM KCl, 10 mM Hepes, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM l-glutamate, 2 mM ATP (Mg salt), 12 mM phosphocreatine, 0.5 mM GTP, and EGTA (0.2 mM; pH 7.4 adjusted with KOH), and EPSCs were evoked by presynaptic action potentials elicited by 1 ms depolarizing pulse (10). When 10 mM EGTA was included in the presynaptic pipettes, isotonicity of the pipette solution was maintained by reducing gluconate. Postsynaptic pipette solution contained 110 mM CsF, 30 mM CsCl, 10 mM Hepes, 5 mM EGTA, and 1 mM MgCl2 added with N-(2, 6-diethylphenylcarbamoylmethyl)-triethyl-ammonium chloride (QX314, 5 mM) to suppress action potential generation. EPSCs were also evoked by extracellular stimulation of presynaptic axons by using a bipolar platinum electrode positioned near the midline of a relatively thick slice (200 μm). The resistance of patch pipette was 5–8 MΩ for presynaptic recordings and 2–4 MΩ for postsynaptic recordings. Current or potential recordings were made with a patch-clamp amplifier (Axopatch 200B, Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Records were low-pass-filtered at 2.5–20 kHz and digitized at 5–50 kHz by a CED 1401 interface (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, U.K.). Phorbol ester was bath-applied by switching superfusates by using solenoid valves. The magnitude of potentiation of EPSCs was evaluated from the mean amplitude of six consecutive events during 5–6 min after phorbol ester application divided by that of six events before application. Values in the text and figures are given as means ± SEM. Experiments were carried at room temperature (22–26°C).

Results

Localization of ɛPKC at the Calyx of Held.

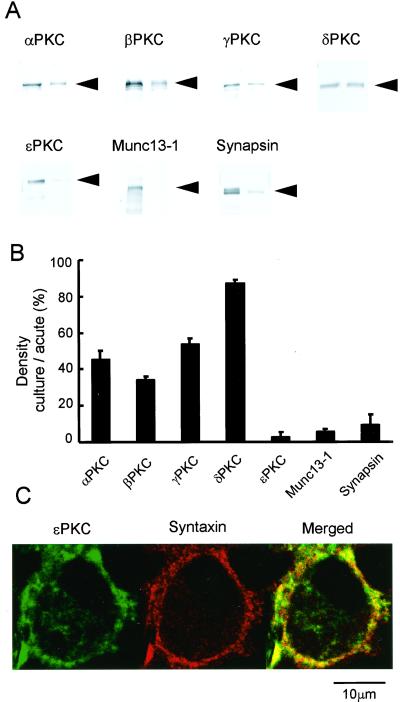

To examine which PKC subspecies is expressed at the calyx of Held nerve terminal, we first carried out Western blot analysis by using PKC subspecies-specific antibodies on the brainstem tissue trimmed from the MNTB region. The tissue expressed all subspecies of PKC examined (α, β, γ, δ, and ɛ), together with other presynaptic proteins, Munc13-1 and synapsin I (Fig. 1A). To assess whether these proteins are expressed at the nerve terminal, we deafferented the projection to the MNTB neurons by removing aVCN on both sides of transverse slices and kept them in organotypic culture. Seven days after deafferentation, EPSCs could no longer be evoked in the MNTB principal cells by extracellular stimulation, suggesting that the afferent fibers were degenerated. In the deafferented slices, expressions of ɛPKC, Munc13-1, and synapsin I in the MNTB region markedly decreased, whereas expressions of other PKC subspecies (α, β, γ, δ) largely remained (Fig. 1 A and B). These results suggest that ɛPKC, as well as synapsin I and Munc13-1, is expressed at the afferent nerve terminal. To further examine this issue, we made immunocytochemical staining of PKC subspecies at the calyx of Held terminal. At a confocal plane, the nerve terminal was identified as a ring structure expressing syntaxin immunofluorescence (Fig. 1C). The ɛPKC immunofluorescence was clearly observed at the terminal, with its distribution largely overlapped with those of presynaptic marker proteins syntaxin (Fig. 1C) and synapsin I (data not shown), whereas immunofluorescence signal for other PKC subtypes (α, β, γ, and δ) was much less clear in the nerve terminal. The immunofluorescence for γPKC was found mainly in the area surrounding the calyces and overlapped with the glial marker protein S-100 (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Presence of ɛPKC at the calyx of Held nerve terminal. (A) Immunoblottings for different PKC isozymes (α, β, γ, δ, and ɛ), and Munc13-1, and synapsin I on tissues trimmed from the MNTB region in acute slices (left lanes) and in deafferented slices kept 7 days in organotypic culture (right lanes). (B) Densitometric quantification of immunoreactivities. Immunoblot densities of deafferented tissues were normalized to those of intact tissues for PKC isozymes, Munc13-1, and synapsin I. Bar graphs indicate mean and +SEMs here and in Fig. 3. Data derived from three samples of three animals each for deafferented and control tissues. (C) ɛPKC immunofluorescence (labeled green with fluorescein), syntaxin immunofluorescence (red with Alexia fluor 568), and their overlap (yellow) at the calyx of Held terminal.

Phorbol Ester Induces Translocation and Autophosphorylation of ɛPKC at the Calyceal Nerve Terminal.

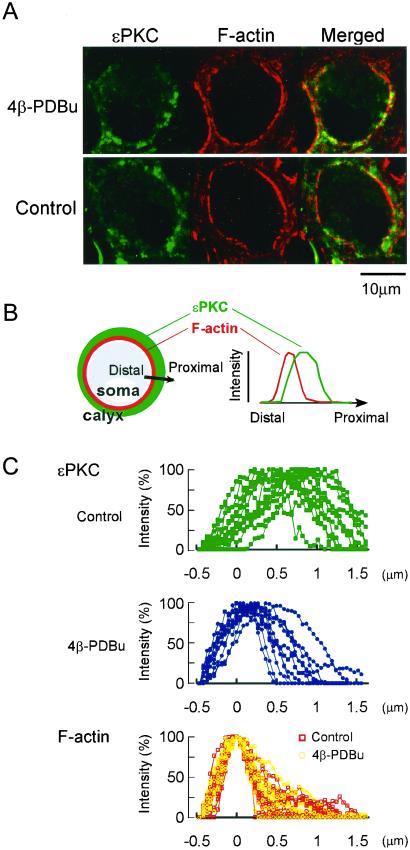

On activation by phorbol ester, PKC translocates from cytosol to membrane in leukemic cells (23) and secretory cells (4–6). We examined whether the translocation of ɛPKC can be observed at the nerve terminal. For this purpose, we used phalloidin conjugated with Alexa fluor 568 for staining F-actin. The F-actin fluorescence signal overlapped with syntaxin immunofluorescence (data not shown), implying that F-actin is expressed predominantly at the presynaptic terminal. Relative to the syntaxin immunofluorescence, F-actin signal was confined to the distal end of terminal just inside the plasma membrane (Fig. 2 A and C). The ɛPKC immunofluorescence was diffusely distributed throughout the nerve terminal, with its peak at 0.62 ± 0.07 μm proximal to the peak of F-actin signal (n = 15, Fig. 2C). The proportion of ɛPKC fluorescence signal overlapped with F-actin signal was 23 ± 2% (n = 12). When the phorbol ester 4β-PDBu (1 μM) was systemically applied, the peak of ɛPKC signal was found translocated toward the synaptic side by 0.38 μm, to 0.24 ± 0.04 μm (n = 29) from the peak of F-actin signal (Fig. 2C). Concomitantly, the overlap between the ɛPKC and F-actin fluorescence became significantly greater (39 ± 1%, n = 30, Fig. 2A). By contrast, the inactive analog 4α-PDBu (1 μM) had no such effect, with the peak of ɛPKC remaining at 0.65 ± 0.06 μm (n = 20, data not shown) from that of F-actin signal, with no change in their overlap (22 ± 2%, n = 30). Thus, on activation, ɛPKC undergoes unidirectional translocation toward the synaptic side.

Figure 2.

Unidirectional translocation of ɛPKC on activation by phorbol ester. (A) ɛPKC immunofluorescence (green), phalloidin staining of F-actin (labeled red with Alexa fluor 568), and their overlap (yellow). On stimulation with 4β-PDBu (1 μM), ɛPKC translocated toward the synaptic side, resulting in a greater overlap with F-actin (yellow, Upper). (B) Schematic drawings explaining the method of densitometric measurements of the immunofluorescence intensity. The intensity was measured along the distal-proximal axis across the calyx of Held terminal. (C Bottom, red and yellow) Intensity profiles of phalloidin normalized to the peak intensity (ordinate) and aligned at the peak (red, defined as 0 μm in abscissa, 12 data sets from three experiments are shown). The phalloidin signal remained similar after application of 4β-PDBu (yellow, 12 data sets from three experiments). (Top, green) Intensity profiles of ɛPKC immunofluorescence (12 data sets from three experiments). The individual fluorescence intensities were normalized to the peak intensity and aligned according to the distance from the peak of phalloidin signal measured along the same line (abscissa). (Middle, blue) Intensity profiles of ɛPKC immunofluorescence after 4β-PDBu application (12 data sets from three experiments). Note the shift in intensity profiles of ɛPKC immunofluorescence toward the peak of actin/phalloidin profile.

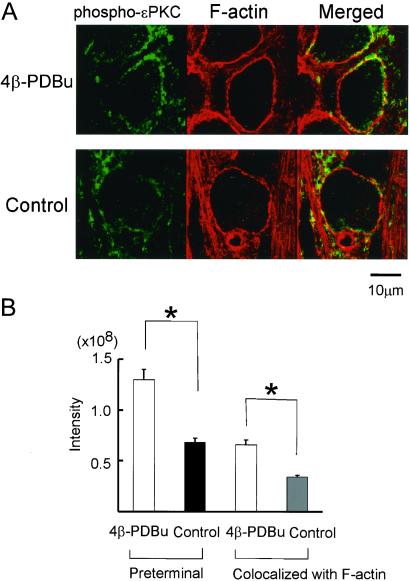

It is thought that the phosphorylation of PKC accompanies its translocation (24). By using a specific antibody against the phosphorylated ɛPKC at the autophosphorylation site (Ser-719), we examined whether the translocation of ɛPKC is accompanied by its autophosphorylation. Phosphorylated ɛPKC immunofluorescence was found at the calyx terminal (Fig. 3A), which was significantly increased by application of 1 μM 4β-PDBu (by 91% of control, Fig. 3B), whereas the inactive 4α-PDBu (1 μM) had no effect (data not shown). The phosphorylated ɛPKC immunofluorescence overlapped with F-actin fluorescence also increased after 4β-PDBu application (by 94%, Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Autophosphorylation of presynaptic ɛPKC on activation by phorbol ester. (A) Calyceal nerve terminals were stained with an antibody against phosphorylated ɛPKC (at Ser-719). Immunoreactivity for the phosphorylated ɛPKC (green) was stronger after application of 4β-PDBu (1 μM, Upper) than control without 4β-PDBu (Lower). Overlap of phosphorylated ɛPKC with F-actin (yellow) increased after phorbol ester application. (B) The immunofluorescence intensities of phosphorylated ɛPKC in the preterminal, and those overlapped with phalloidin. Data derived from three animals each for control and 4β-PDBu application. Asterisks indicate significant difference in unpaired Student's t test (P < 0.05).

Ca2+ Dependence of the Phorbol Ester-Induced Synaptic Potentiation.

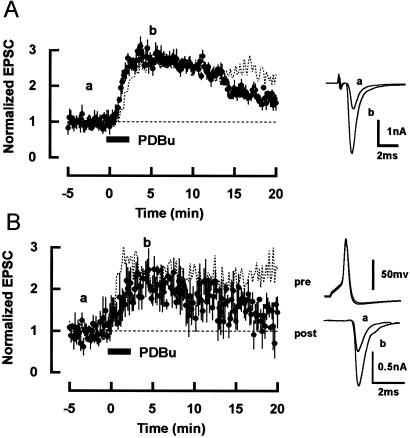

In contrast to the conventional PKC, the novel PKC isoforms do not possess a Ca2+ binding (C2) domain, implying that their activation is independent of Ca2+ (25, 26). Thus we examined whether the PESP at this synapse is Ca2+ dependent. We first examined the effect of EGTA tetra-acetoxymethyl ester (EGTA-AM, 0.2 mM). After incubating slices for 1 h with EGTA-AM, 4β-PDBu (0.5 μM) potentiated EPSCs (Fig. 4A) to a similar extent as in normal condition (10), albeit a small difference in the time course of potentiation. Under these conditions, EGTA-AM must reduce intraterminal Ca2+ concentration because the initial Ca2+-dependent component of recovery time after synaptic depression by a train of 300 Hz stimuli (27) was abolished (n = 3, data not shown). For a more direct test, we next loaded EGTA (10 mM) into calyces via presynaptic whole-cell pipettes in simultaneous pre- and postsynaptic recordings. After loading EGTA, application of 4β-PDBu (0.5 μM) potentiated EPSCs evoked by presynaptic action potentials (Fig. 4B) by 112 ± 7% (n = 5), which is similar in magnitude to the PESP in simultaneous pre- and postsynaptic recordings with 0.2 mM EGTA in presynaptic pipette (116 ± 11%, n = 5) (10). These results indicate that the PESP at the calyx of Held synapse is largely Ca2+ independent.

Figure 4.

Ca2+-independent potentiation of EPSCs induced by phorbol ester. (A) After incubating slices with EGTA-AM (200 μM for 1 h), 4β-PDBu (0.5 μM, applied for 2 min at a bar) potentiated EPSCs (filled circles, mean values, and SEMs from four neurons). Dotted line represents the average potentiation of EPSCs by 4β-PDBu (0.5 μM) without EGTA-AM in single electrode recordings (10). Sample records of averaged EPSCs before (a) and after (b) 4β-PDBu application are superimposed and shown on the Right. (B) In simultaneous pre- and postsynaptic whole-cell recordings, 4β-PDBu (0.5 μM) potentiated EPSCs in the presence of EGTA (10 mM) in presynaptic pipettes (filled circles, n = 5; 4β-PDBu was applied 10 min after rupture). EPSCs (Right, post) were evoked by presynaptic action potentials (Right, pre) elicited by brief depolarizing pulses. Sample records before (a) and after (b) 4β-PDBu application are superimposed. Dotted line indicates the average potentiation of EPSCs induced by 4β-PDBu (0.5 μM) with 0.2 mM EGTA in presynaptic pipettes (10).

Discussion

The ɛ isoform of PKC is a new member of PKC family and is thought to be involved in diverse cell functions such as gene expression (28), cell adhesion (29), secretion (3, 5, 30), and endocytosis (31). ɛPKC is widely distributed in the central nervous system and has been found in hippocampal nerve terminals (32), although its presynaptic role has not been identified. Our results indicate that ɛPKC is expressed at the calyx of Held terminal in the rat brainstem. On stimulation by phorbol ester, ɛPKC underwent autophosphorylation and translocation toward the membrane of the synaptic side. Concomitantly, EPSCs were potentiated in a Ca2+-independent manner. These results taken together suggest that the Ca2+-independent ɛPKC largely mediates the PESP at the calyx of Held synapse. It has been reported that the magnitude of PESP at hippocampal synapse is normal in mice lacking γPKC (33). Therefore, ɛPKC might also mediate the PESP at hippocampal synapses. γPKC is localized at the nerve terminal and somata of cerebellar Purkinje cells (2). It remains to be seen whether γPKC mediates the PESP at the cerebellar inhibitory synapse (34).

In the present study, after phorbol ester application, ɛPKC translocated toward the synaptic side of the nerve terminal. Translocation of PKC on activation has been documented in a variety of secretory cells (3–6) and leukemic cells (23). Here, we demonstrate that ɛPKC can translocate in the nerve terminal. In contrast to the PKC translocations previously reported, this presynaptic translocation was unidirectional. If the ɛPKC translocation is directed toward its target (24), the target molecules must reside near the plasma membrane on the synaptic side of the nerve terminal. It has been reported that ɛPKC, but not other PKC isozymes, can directly bind with F-actin (35, 36), and this interaction maintains the ɛPKC in a catalytically active conformation (36). In epithelial cells, ɛPKC can regulate endocytosis via F-actin (31). Actins regulate exocytosis of dense cored vesicles in neurosecretory cells (35) although less is known for small vesicles. In secretory cells, phorbol ester disrupts cortical F-actin and increase exocytosis (37–39). By analogy, at the nerve terminal, it may be speculated that ɛPKC activated by phorbol ester might interact with F-actin and change its conformation, thereby increasing transmitter release.

After reducing presynaptic Ca2+ concentrations by EGTA-AM or intracellular loading of EGTA, the PESP was relatively short-lasting, suggesting that the late component of the PESP is Ca2+ dependent. Although cPKCs were not detectable in our immunocytochemical study, weakly expressed cPKCs at the calyceal nerve terminal might still be involved in the Ca2+-dependent late component of PESP. Because synaptic transmission largely remained unblocked in the presence of EGTA (10 mM) in calyces (40), our results do not rule out the possibility that cPKCs are localized within the Ca2+ microdomain where EGTA cannot reach (41) and involved in PESP. At this synapse, the PESP is mediated by both PKC and the Doc2α-Munc13-1 interaction (10) as at the neuromuscular junction (42), although it is not known whether Munc13-1 and PKC are colocalized at the same nerve terminal. The presynaptically injected Mid peptide, which blocks the Doc2α-Munc13-1 interaction, attenuates PESP particularly at the late component (10). Doc2α possesses C2 domain and the Doc2α-Munc13-1 interaction is Ca2+ dependent, at least in vitro (43). Thus, the Doc2α-Munc13-1 interaction might also mediate the Ca2+-dependent late component of PESP.

PKC can be activated by diacylglycerol, cis-unsaturated fatty acid, and lysophosphatidylcholine (44). Although natural messages that activate ɛPKC at the calyx of Held remain to be identified, this large nerve terminal provides a model system for elucidating the molecular mechanism underlying the PKC-dependent synaptic modulation, which is widely observed among central synapses.

Acknowledgments

We thank Taro Ishikawa, David Saffen, and Tetsuhiro Tsujimoto for discussion and comments on our manuscript. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture.

Abbreviations

- PKC

protein kinase C

- cPKC

conventional PKC

- PESP

phorbol ester-induced synaptic potentiation

- aVCN

anteroventral cochlear nucleus

- MNTB

medial nucleus of the trapezoid body

- EPSC

excitatory postsynaptic current

- aCSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- EGTA-AM

EGTA tetra-acetoxymethyl ester

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Nishizuka Y. Science. 1992;258:607–614. doi: 10.1126/science.1411571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka C, Nishizuka Y. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:551–567. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.003003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akita Y, Ohno S, Yajima Y, Konno Y, Saido T C, Mizuno K, Chida K, Osada S, Kuroki T, Kawashima S, Suzuki K. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4653–4660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bastani B, Yang L, Baldassare J J, Pollo D A, Gardner J D. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1995;1269:307–315. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(95)00120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong D-H, Forstner J F, Forstner G G. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G31–G37. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.1.G31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yedovitzky M, Mochly-Rosen D, Johnson J A, Gray M O, Ron D, Abramovitch E, Cerasi E, Nesher R. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1417–1420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malenka R C, Madison D V, Nicoll R A. Nature (London) 1986;321:175–177. doi: 10.1038/321175a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shapira R, Silberberg S D, Ginsburg S, Rahamimoff R. Nature (London) 1987;325:58–60. doi: 10.1038/325058a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capogna M, Gahwiler B H, Thompson S M. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1249–1260. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01249.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hori T, Takai Y, Takahashi T. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7262–7267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07262.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J-H, Feng D-P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2576–2580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanse E, Gustafsson B. Neuroscience. 1994;58:263–274. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanton P K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1724–1728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bortolotto Z A, Collingridge G L. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:4055–4062. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Micheau J, Riedel G. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:534–548. doi: 10.1007/s000180050312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Held H. Arch Anat Physiol Anat Abt. 1893;17:201–248. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu L-G, Westenbroek R E, Borst J G G, Catterall W A, Sakmann B. J Neurosci. 1999;19:726–736. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00726.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kajikawa Y, Saitoh N, Takahashi T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8054–8058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141031298. . (First Published June 19, 2001; 10.1073/pnas.141031298) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forsythe I D. J Physiol (London) 1994;479:381–387. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borst J G G, Helmchen F, Sakmann B. J Physiol (London) 1995;489:825–840. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takahashi T, Forsythe I D, Tsujimoto T, Barnes-Davies M, Onodera K. Science. 1996;274:594–597. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoppini L, Buchs P-A, Muller D. J Neurosci Methods. 1991;37:173–182. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90128-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shoji M, Girard P R, Mazzei G J, Vogler W R, Kuo J F. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;135:1144–1149. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)91047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mochly-Rosen D, Gordon A S. FASEB J. 1998;12:35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohno S, Akita Y, Konno Y, Imajoh S, Suzuki K. Cell. 1988;53:731–741. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ono Y, Fujii T, Ogita K, Kikkawa U, Igarashi K, Nishizuka Y. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:6927–6932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang L-Y, Kaczmarek L K. Nature (London) 1998;394:384–388. doi: 10.1038/28645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reifel-Miller A E, Conarty D M, Valasek K M, Iversen P W, Burns D J, Birch K A. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21666–21671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.35.21666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chun J-S, Ha M-J, Jacobson B S. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13008–13012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.13008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zoukhri D, Hodges R R, Sergheraert C, Toker A, Dartt D A. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:C263–C269. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.1.C263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song J C, Hrnjez B J, Farokhzad O C, Matthews J B. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:C1239–C1249. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.6.C1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saito N, Itouji A, Totani Y, Osawa I, Koide H, Fujisawa N, Ogita K, Tanaka C. Brain Res. 1993;607:241–248. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91512-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goda Y, Stevens C F, Tonegawa S. Learn Mem. 1996;3:182–187. doi: 10.1101/lm.3.2-3.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shuntoh H, Taniyama K, Tanaka C. Brain Res. 1989;483:384–388. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prekeris R, Mayhew M W, Cooper J B, Terrian D M. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:77–90. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prekeris R, Hernandez R M, Mayhew M W, White M K, Terrian D M. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26790–26798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muallem S, Kwiatkowska K, Xu X, Yin H L. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:589–598. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.4.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vitale M L, Seward E P, Trifaro J-M. Neuron. 1995;14:353–363. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koffer A, Tatham P E R, Gomperts B D. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:919–927. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borst J G G, Sakmann B. Nature (London) 1996;383:431–434. doi: 10.1038/383431a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adler E M, Augustine G J, Duffy S N, Charlton M P. J Neurosci. 1991;11:1496–1507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01496.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Betz A, Ashery U, Rickmann M, Augustin I, Neher E, Sudhof T C, Rettig J, Brose N. Neuron. 1998;21:123–136. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80520-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Orita S, Naito A, Sakaguchi G, Maeda M, Igarashi H, Sasaki T, Takai Y. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16081–16084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shirai Y, Kashiwagi K, Yagi K, Sakai N, Saito N. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:511–521. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]