Abstract

Collagen and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) play a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP) as a switch between type I and III collagen together with a simultaneous activation of MMPs have been observed in the vaginal wall. The aim of this study was to evaluate the Advanced Glycation End (AGE) products, ERK1/2 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β/Smad pathway expression in muscularis propria in women with POP compared with control patients. We examined 20 patients with POP and 10 control patients treated for uterine fibromatosis. Immunohistochemical analysis using AGE, RAGE, ERK1/2, Smads-2/3, Smad-7, MMP-3, and collagen I-III, TIMP, and α-SMA were performed. Smad-2/3, Smad-7, AGE, ERK1/2, p-ERK, and p-Smad3 were also evaluated using Western-blot analysis. POP samples from the anterior vaginal wall showed disorganization of the normal muscularis architecture. In POP samples, AGE, ERK1/2, Smad-2/3, MMP-3, and collagen III were upregulated in muscularis whereas in controls, Smad-7 and collagen I were increased. The receptor for AGEs (RAGE) was mild or absent both in controls and prolapse. We demonstrated the involvement of these markers in women with POP but further studies are required to elucidate if the overexpression of these molecules could play a crucial role in the pathophysiology of POP disease.

Keywords: Advanced Glycation End products, extracellular matrix, immunological staining, muscularis, POP, transforming growth factor-β/Smads

Introduction

Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP) refers to the abnormal descent of an organ or a part of it from its primitive anatomical location. Because 40% of women between 45 and 85 show clinical evidence of POP, this condition represents a real public health issue, affecting noticeably female quality of life1–3 and representing the main indication for hysterectomy in post-menopause, which is currently the most common intervention although demolitive surgery, when performed alone, exposes patients to a risk of recurrence of 9–13%.4

Anatomical and functional integrity of the pelvic floor is strictly related to its connective scaffolding, which guarantees mechanical support and stability to organs. Ligaments superiorly and muscles inferiorly hang vagina and uterus in the pelvis. This architecture can be effectively compared with the one of a suspension bridge: when muscles contract, ligaments become stretched, giving shape and solidity to pelvic organs. If tissues are not supported by an adequate collagenic framework, ligaments would anchor to a shapeless mass, and the whole structure would collapse downward.5,6

Prolapse pathophysiology remains still unclear but several studies have demonstrated that in the muscularis vaginal wall of POP patients, connective tissue plays a pivotal role in disorganizing the architecture of the muscularis. Abnormal levels of connective tissue within the muscularis of the anterior wall of the vagina in POP are associated with a switch from collagen I, composed of tough fibers able to bear high traction forces in connective tissue forming the pelvic floor, to collagen III, with thinner and more fragile fibers.7,8 In addition to this, it has been reported that an imbalance in Extracellular Matrix (ECM) turnover involving matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) causes overactivation.9,10 MMP can be specifically inhibited by Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase (TIMP), thus, both MMP and TIMP maintain the integrity of ECM and are implicated in remodeling the excessive matrix via their dynamic balance. Therefore, this family of enzymes could be related to the physiopathology of POP.

Growing interest has been shown for Advanced Glycation End (AGE) products, the products of non-enzymatic glycation and oxidation of proteins and lipids, because their interaction with the receptor for AGEs (RAGE) and other receptors activate several pathways involved in many human diseases characterized by a deregulation of collagen metabolism.11–14

It has been demonstrated that AGEs could also take part in the pathophysiology of POP as Chen et al. found that collagen I levels were decreased in prolapse tissue, and the expression of AGEs in the same tissue was concomitantly increased.15 Recent in vitro studies demonstrated that the interaction between AGE and its receptor RAGE seem capable of inducing connective remodeling through MMP-1, TIMP, and changes in p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and nuclear factor (NF)-kB.16

Other pathways may also be involved in the synthesis and degradation metabolism of collagen. ERK1/2, numbered in the MAPK family, can mediate this induction by increasing MMP levels,17 and it seems able to recruit, in a transforming growth factor (TGF)-β–independent manner, Smads proteins, which eventually affect collagen synthesis and deposition.18–20 There are also studies about the altered expression of TGF-β in women with POP, showing that this cytokine may directly play an important role in pelvic organ disorders.21

In light of this, the aim of our study was to evaluate the changes of AGEs, ERK, and TGF-β/Smad proteins expression in the muscularis propria of the anterior vaginal wall of patients affected from POP compared with controls.

Materials and Methods

The study was set by recruiting a total number of 30 patients of female gender. Vaginal tissues were obtained from 10 women without symptoms of urinary incontinence or uterine prolapse, who underwent laparotomic hysterectomy for uterine fibromatosis or other benign gynecological disorders (control group) and from 20 patients suffering from at least stage III POP, who underwent colpohysterectomy followed by anterior or posterior plastic surgery (case group).

Women were selected following specific criteria, taking into account the average age, which was 57 SD ± 14 in both groups, and the selection of samples was carried out after careful, pre-operative clinical and case history evaluations.

Women with a history of vulvar, vaginal, or cervical neoplasia, connectival pathologies, dystrofic vulvar, or vaginal lesions, Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT), and incontinence were excluded from the study.

Some women showed risk factors for POP, such as vaginal delivery, episiotomy, and/or perineal lacerations and Kristeller maneuver. None of the subjects included in our study had a history of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), constipation, and neurodegenerative diseases. During clinical evaluation, patients had a Body Mass Index (BMI) between 25 and 28 and an anovulvar distance higher than 3 cm. POP biopsies were collected during vaginal plastic surgery, whereas control fragments were provided during abdominal hysterectomy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Risk Factors for POP.

| Cases (20) | Cases % | Controls (10) | Controls % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| COPD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Constipation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Neurodegenerative diseases | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Varicose veins | 9 | 45 | 1 | 10 |

| One or more spontaneous delivery | 20 | 100 | 10 | 100 |

| Episiotomy | 13 | 65 | 7 | 70 |

| Perineal tears | 7 | 35 | 4 | 40 |

| Operative vaginal delivery | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kristeller maneuver | 7 | 35 | 7 | 40 |

| Fetal macrosomia | 2 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 25 < BMI < 28 | 20 | 100 | 10 | 100 |

| Anovulvar distance > 3 cm | 20 | 100 | 10 | 100 |

Abbreviations: POP = pelvic organ prolapse; HRT = hormone replacement therapy; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BMI = body mass index.

All patients have given their consent to the processing of personal data, and this study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethic Committee (no. 36944).

Tissue Acquisition and Preparation

Samples of anterior vaginal wall were collected during surgery, cleaned, and immersed in 4% buffered formalin for 3 hr at room temperature for histological and IHC analysis. Biopsy specimens were also processed for protein extraction by homogenization in lysis buffer 2× concentrated in presence of proteases and phosphatases inhibitor.

Histology and IHC

Fragments were previously fixed and embedded in low temperature-fusion paraffin, and serial sections of 3 μm were employed for several histological stainings. H&E was performed to evaluate the general architecture of the anterior vaginal wall; Masson Trichrome and Van Gieson were used to identify collagen deposition and elastic fibers, respectively. Stained sections were observed using an Olympus BX51 Light Microscope (Olympus Optical Co. Ltd.; Tokyo, Japan).

For IHC analysis, sections were incubated in methanol and 3% hydrogen peroxidase solution for 40 min and then rinsed in PBS. Thereafter, samples were incubated overnight at 4C with polyclonal antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; Santa Cruz, CA) to Smad-2/3 (sc- 6202; dilution 1:400), p-Smad3 (sc-130218; dilution 1:100), Smad-7 (sc-9185; dilution 1:400), TGF-β1 (sc-146; dilution 1:400), Collagen I (sc-8784; dilution 1:400), Collagen III (sc-8781; dilution 1:400), and MMP-3 (sc-6839; dilution 1:400), TIMP1 (sc-6834; dilution 1:500), α-SMA (sc-32251; dilution 1:400), AGE (ab23722: Abcam; Cambridge, UK; dilution 1:50), RAGE (pA1-075: Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.; Waltham, MA; dilution 1:50), and ERK1/2 (pA1-075: Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.; dilution 1:50) and p-ERK (sc-7383; dilution 1:100). Samples were then rinsed with PBS for 5 min and incubated with a labeled streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase conjugate kit (Dako LSAB plus, cod.K0675, DakoCytomation; Milan, Italy). After rinsing in PBS for 10 min, the sections were incubated with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine-tetrahydrochloride (DAB; k3468, DakoCytomation) for 1–3 min. Last, the samples were counterstained with Mayer’s Hematoxylin and observed under a photomicroscope Olympus BX51 Light Microscope (Olympus Optical Co. Ltd.).

To demonstrate the immunoreaction specificity, negative and positive controls were performed for all immunoreactions. For negative controls, the primary antibody was replaced (same dilution) with normal serum from the same species. For positive controls, the following tissues were tested: arteriosclerotic plaque was used for AGE (ab23722: Abcam; dilution 1:100); diabetic vessels for RAGE (pA1-075: Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.; dilution 1:50); human prostate cancer for ERK1,2 (pA1-075: Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.; dilution 1:100); Inflammatory Bowel Disease for Smad-2/3; normal colon for Smad-7; intestinal stenotic tract for Collagen I and III; high-grade glioblastoma for MMP-3 and TIMP1; muscularis mucosae and muscularis propria of normal colon for α-SMA (used at same dilution of POP samples and control samples; see Supplemental Figs. 1 and 2).

Observations were processed with an image analysis system (IAS; Delta; Rome, Italy) and were independently performed by two pathologists (A.V., R.S.) in a blinded fashion.

Quantitative Digital Image Analysis of Immunohistochemical Staining and Statistical Analyses

Quantitative comparison of immunohistochemical staining was measured by digital image analysis using ImageJ public domain software (W.S. Rasband, ImageJ, U.S. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD; imagej.nih.gov/ij/). IHC-stained samples were implemented using the open-source image processing software ImageJ (imagej.en.softonic.com), after installing the IHC profiler plug-in. The IHC images employed were stained with DAB and Hematoxylin, and four fields for each sample were randomly chosen and photographed at the same magnification. The microphotographs underwent spectral deconvolution method of DAB/Hematoxylin. For each of the photographs, the software analyzed the pixel intensity splitting it in threshold values: negative, low positive, positive, and high positive. Taking this into account, we obtained the whole immunopositivity by summing the three different grades of positivity.

The microphotographs were saved as digital images, each of them having the same amount of pixels. This procedure was carried out to get images with comparable digital features and repeated for each tested antibody. Then, the amount of immunostaining was analyzed through the IHC profiler software. The immunopositivity was expressed as a percentage in the total software-classified areas, and the data obtained were plotted on histograms.

The results were reported as a percentage in the total software-classified areas, and the data obtained were plotted on histograms and expressed as mean ± SD; p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.22

In Vitro Analyses

The evaluation of markers levels was performed on proteins extracted by homogenization of patients tissues in lysis buffer 2× (Cell Signaling Technology-9802; Danvers, MA), added with proteases and phosphatases inhibitors (Cell Signaling Technology-9803). The amount of proteins for each of the samples was calculated with Bradford assay, and an electrophoresis was run in denaturant condition. The protein was transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and incubated with the following primary antibodies: Smad-2/3 (sc-6202), p-Smad3 (sc-130218), Smad-7 (sc-9185), AGE (ab23722: Abcam), ERK1/2 (44-6544: Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), p-ERK (sc-7383) at concentrations suggested by datasheets. Finally, the identification of the specific chemiluminescent bands was performed by exposure of the nitrocellulose membrane, previously incubated with the corresponding secondary antibodies, to enhanced chemiluminescent (ECL; Chemiluminescent Substrate Pico. COD. EMP001005; Euroclone; Milan, Italy).

Results

Whole Mount Tissue Histology

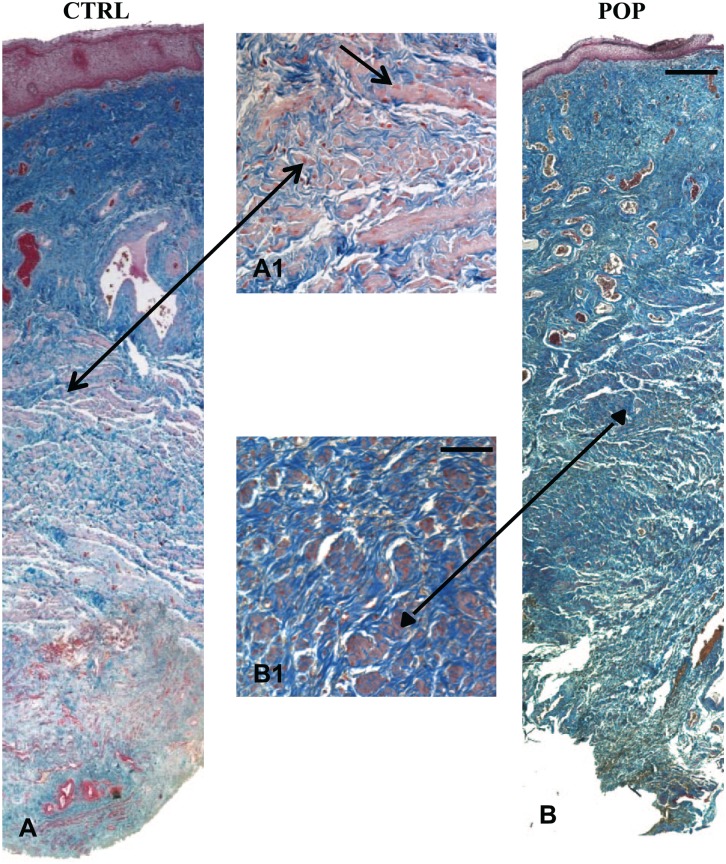

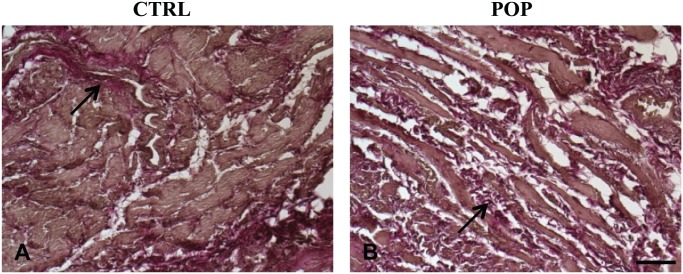

Histomorphological evaluation with H&E (data not shown) and Masson’s Trichrome allowed an appreciation that all the layers constituting the anterior vaginal wall were present; there was no inflammatory infiltration of the lamina propria or subepithelium in any of the samples, both in control (Fig. 1A) and POP samples (Fig. 1B). In prolapsed fragments, remodeling of the muscular layer architecture with a distortion of smooth muscle cells (SMC) was evident, together with a simultaneous increase of collagen deposition (Fig. 1B) and a reduction of elastin fibers (Fig. 2B; arrow). In the control samples, SMCs were more tightly packed, organized in orientated fibers, with a more regular distribution of elastic fibers (arrow; Fig. 2A).

Figure 1.

Masson Trichrome. Histomorphological features of anterior vaginal wall. The control fragments showed the typical compact and well-organized muscle layer with a regular disposition of SMCs (A–A1; arrow). On the opposite side, in the prolapsed specimens, fibers were disrupted and encircled by an increased amount of collagen (B–B1; arrowhead). The figures were the result of a montage/composite images of three consecutive fields captured at 5X. Original magnification (O.M.) 5× and 20×: scale bar = 200 µm and 50 µm. Abbreviations: SMC, smooth muscle cell; CTRL, control; POP, pelvic organ prolapse.

Figure 2.

Weigert Van Gieson. Histomorphological features of anterior vaginal wall. In pathological specimens, a marked rearrangement of the muscular layer with reduction of elastin fibers was evident (B) with respect to CTRLs (A). O.M. 10×, scale bar = 100 µm. Abbreviations: CTRL, control; POP, pelvic organ prolapse.

Whole Mount Tissue IHC and Western Blot Analysis

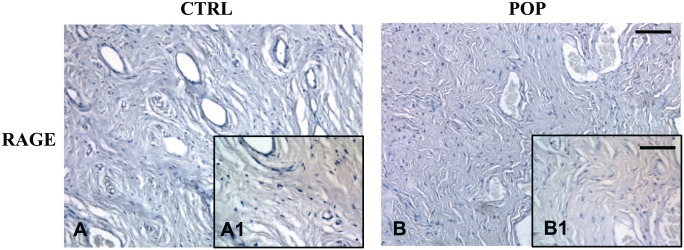

IHC for RAGE result was mild or absent, both in pathological and control specimens (Fig. 3A, A1–B, B1).

Figure 3.

IHC for RAGE. Immunostaining for RAGE antibody did not demonstrate any significant difference between CTRLs (A, A1) and POP samples (B, B1). O.M. 10×, scale bar = 100 µm; 40×, scale bar = 25 µm. Abbreviations: CTRL, control; POP, pelvic organ prolapse.

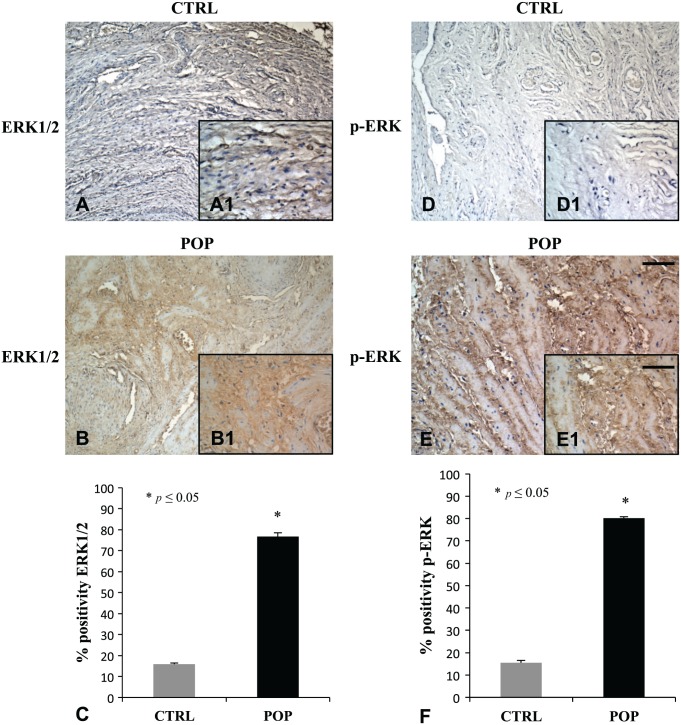

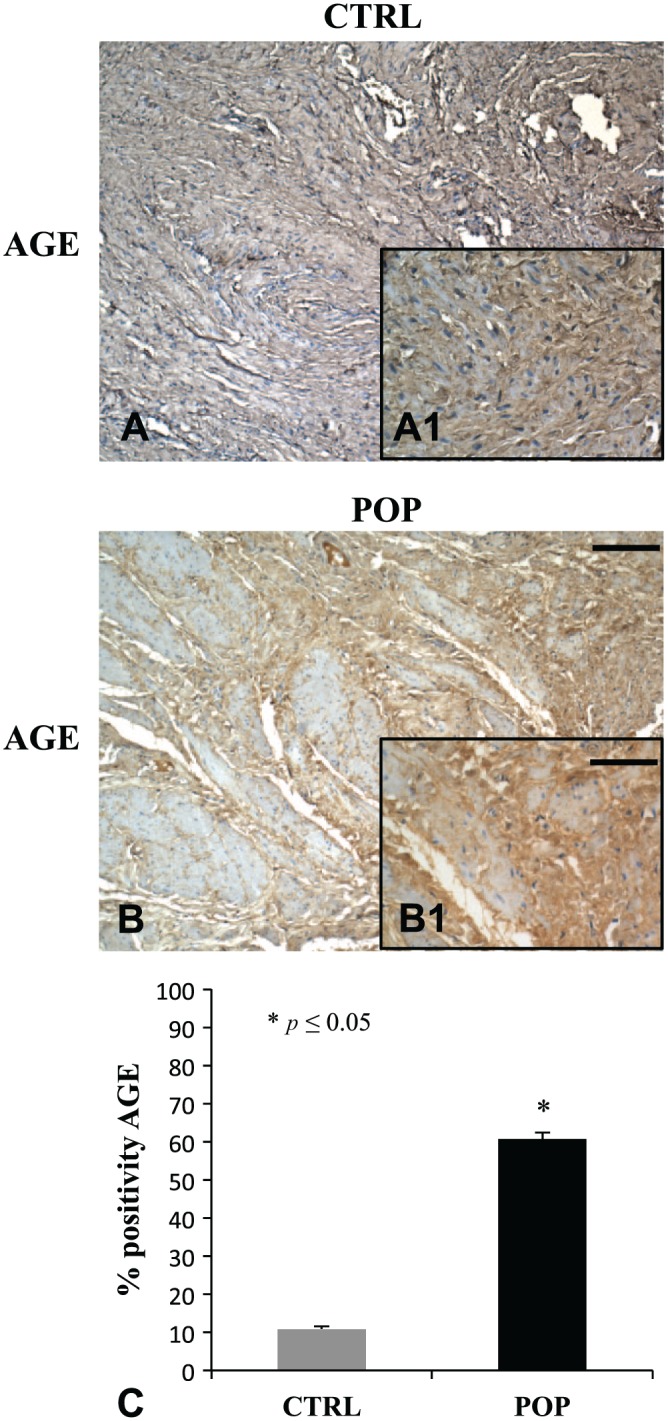

Immunostaining and its quantitative analysis demonstrated in the muscularis propria a weak positivity for AGE in control fragments (Fig. 4A, A1), while reported was a relevant enhancement of the immunopositivity for the same antibody in POP samples (Fig. 4B, B1). The disposition of the antibody was not casual, because it encircled myocytes (Fig. 4A–B). Immunohistochemical evaluations for ERK1/2 (Fig. 5B, B1) and p-ERK (Fig. 5E, E1) showed a marked overexpression in muscularis of prolapsed tissues, while it was mild in controls (Fig. 5A, A1 and D, D1) for ERK1/2 and p-ERK, respectively.

Figure 4.

IHC for AGE. In the muscularis propria of pathological fragments, immunostaining for AGE showed a significant increase in expression (B, B1), when compared with specimens from CTRL patients (A, A1). The disposition of the immunopositivity encircled peculiarly all the muscle fibers in both samples (A and B). O.M. 10×, scale bar = 100 µm; 40× scale bar = 25 µm. Quantitative analysis (C). Abbreviations: AGE = Advanced Glycation End product; CTRL, control; POP, pelvic organ prolapse.

Figure 5.

IHC for ERK1/2 and p-ERK. In muscularis propria, a remarkable increase of ERK1/2 and p-ERK expression was evident in fragments from patients with prolapse (B–B1, E–E1), in contrast with the mild or absent immunopositivity observed in CTRLs specimens (A–A1, D–D1). The disposition of the immunopositivity duplicated the one detected with AGE. O.M. 10×, scale bar = 100 µm; 40× scale bar = 25 µm. Both data were consistent with the ones obtained with quantitative analysis (C–F). Abbreviations: AGE = Advanced Glycation End product; CTRL, control; POP, pelvic organ prolapse.

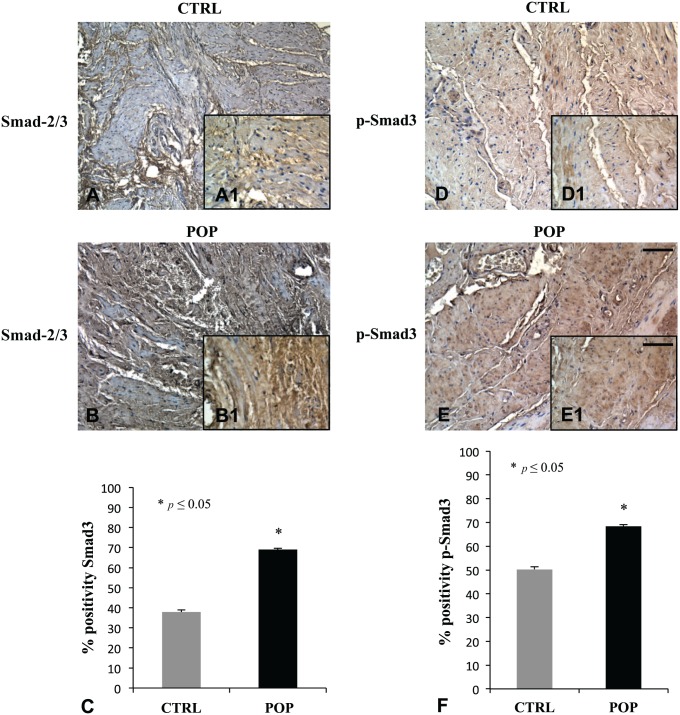

IHC analysis for TGF-β did not show any significant difference in POP and controls, as if transforming growth is not involved in Smads activation (data not shown). Smad-2/3 and p-Smad3 immunohistochemical evaluation demonstrated a high positivity in POP fragments (Fig. 6B, B1 and E, E1 respectively), while it was mild in controls (Fig. 6A, A1 and D, D1, respectively).

Figure 6.

IHC for Smad-2/3 and p-Smad3. The positivity detected for Smad-2/3 and p-Smad3 was considerably different between the two groups, as it appeared to be higher in prolapsed tissues (B–B1, E–E1) than in CTRL fragments (A–A1, D–D1) as confirmed by quantitative evaluation (C–F). O.M. 10×, scale bar = 100 µm; 40× scale bar = 25 µm. Abbreviations: CTRL, control; POP, pelvic organ prolapse.

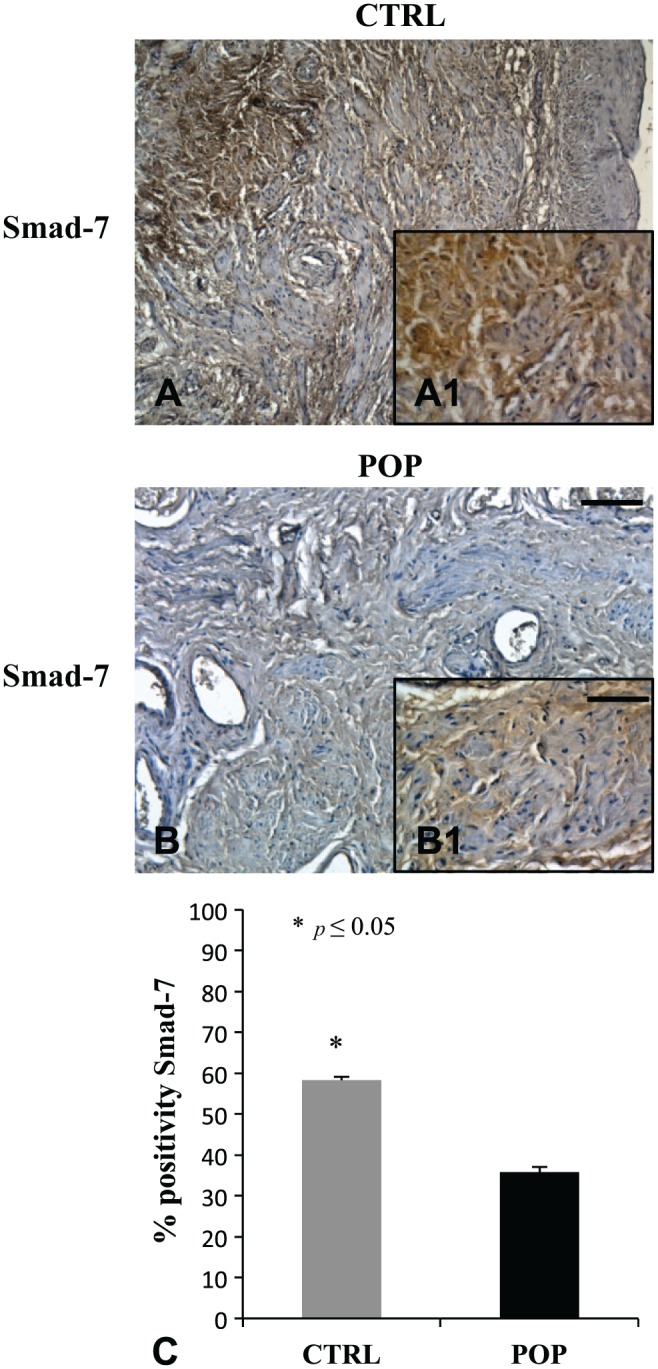

On the contrary, Smad-7, the inhibitor of the TGF-β/Smads pathway, was significantly more immunopositive in controls (Fig. 7A, A1) than in pathological specimens (Fig. 7B, B1).

Figure 7.

IHC for Smad-7. Smad-7, the inhibitor of the TGF-β/Smads cascade, was more expressed in CTRL specimens (A, A1) when compared with prolapsed fragments (B, B1) where immunopositivity was mild. O.M. 10×, scale bar = 100 µm; 40× scale bar = 25 µm. Quantitative analysis (C). Abbreviations: TGF, transforming growth factor; CTRL, control; POP, pelvic organ prolapse.

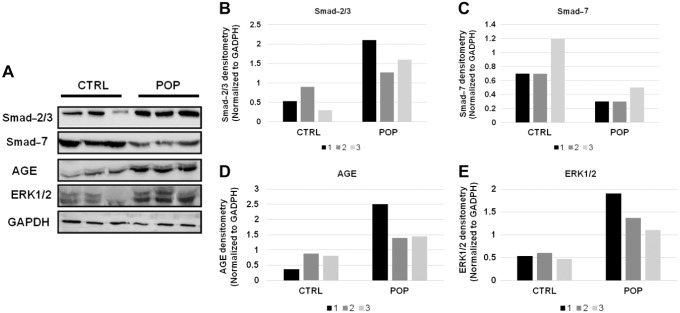

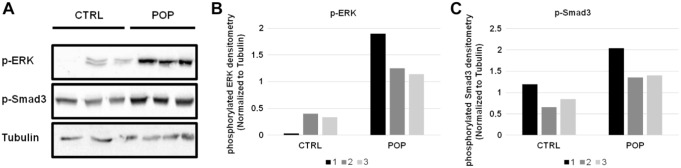

These IHC data agreed with Western blot analysis performed on a representative tissue extracted samples for the same markers. Indeed, we can see the upregulation of ERK1/2 (Fig. 8) and its phosphorylated form (Fig. 9) in POP samples, as well as the increased levels of AGE protein in the same samples (Fig. 8). In association with this, we identified the downmodulation of Smad-7 and the increased levels of Smad-2/3 (Fig. 8) and p-Smad3 (Fig. 9) proteins in POP specimens.

Figure 8.

Western blot evaluation of Smad-2/3, Smad-7, AGE, and ERK1/2, in CTRL and POPs samples (A) and relative densitometry quantization (B–C–D–E). Abbreviations: AGE = Advanced Glycation End product; CTRL, control; POP, pelvic organ prolapse.

Figure 9.

Western blot evaluation of p-ERK and p-Smad3 in CTRL and POPs samples (A) and relative densitometry quantization (B–C). Abbreviations: CTRL, control; POP = pelvic organ prolapse.

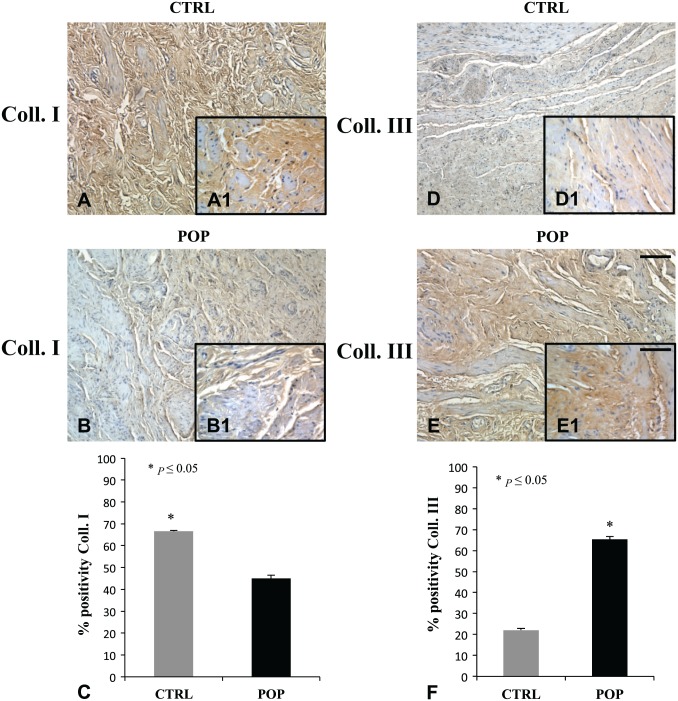

Collagen I and III molecules were expressed in both groups (Fig. 10), even though there was a considerable difference in the immunoreactions. Collagen I resulted predominantly in control tissues (Fig. 10A, A1), while there was an enhancement in collagen III expression in lamina propria and muscular layer in POP samples (Fig. 10E, E1). Particularly, the ratio between collagen I and collagen III in the control samples versus POP samples was 4.5 times higher.

Figure 10.

IHC for Collagen I and Collagen III. Collagen I was increased in CTRL specimens (A, A1) when compared with POP fragments (B, B1). On the contrary, Collagen III showed an increase of immunopositivity in prolapse (E, E1) compared with CTRL (D, D1). O.M. 10×, scale bar = 100 µm; 40× scale bar = 25 µm. Quantitative evaluations results (C–F). Abbreviations: COLL., collagen; CTRL, control; POP = pelvic organ prolapse.

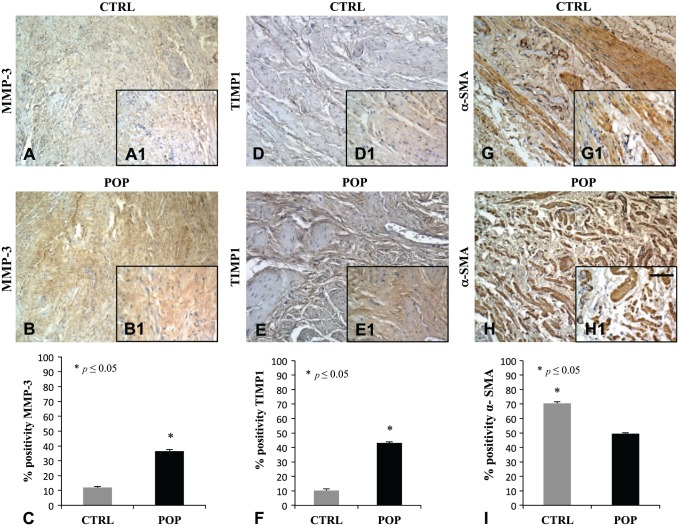

Immunohistochemical evaluation for MMP-3 and TIMP showed a marked positivity in muscularis propria of prolapsed fragments (Fig. 11B, B1–E, E1) when compared with controls (Fig. 11A, A1–D, D1). The α-SMA immunoreaction was located in typical sides with a regular distribution of SMCs in the muscularis of control specimen, whereas in prolapsed fragments, the immunopositivity appeared displaced by an increased presence of connective tissue deposition (Fig. 11G, G1–H, H1). These data where confirmed by quantitative analysis (Fig. 11C–F–I).

Figure 11.

IHC for MMP-3, TIMP1, and α-SMA. Immunohistochemical evaluation for MMP-3 and TIMP showed a high expression in muscularis propria of prolapsed fragments (B, B1–E, E1) when compared with CTRLs (A, A1–D, D1). The α-SMA was regularly distributed in SMCs in the muscularis of the CTRL specimen (G, G1), with respect to prolapsed fragments (H, H1), where it was displaced by an increased presence of connective tissue deposition. O.M. 10×, scale bar = 100 µm; 40× scale bar = 25 µm. Quantitative analysis (C–F–I). Abbreviations: MMP = matrix metalloproteinase; TIMP = Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase; CTRL, control; POP = pelvic organ prolapse; SMC, smooth muscle cell.

Discussion

The pathophysiology of POP is multifactorial and incompletely understood although recent evidence has suggested that besides environmental factors and genetic predisposition, structural modifications of muscularis propria together with changes in composition of connective tissue play a pivotal role.

In accordance with previous observations,23–26 this study also demonstrated both in Trichromic and αSMA immunolocalization that in muscularis propria, SMCs appeared to be more disorganized and disrupted in the anterior vaginal wall of the POP patient, when compared with controls. Bundles of prevalent collagen III were interspersed between muscular fibers, resulting in alteration of the normal architecture of the muscularis. A phenotypic switch from SMCs to myofibroblasts may be the underlying cause of these structural modifications, as Platelet Derived Growth Factor (PDGF) was also found overexpressed in POP samples, and it may be involved in this metaplastic trans-differentiation cellular transition from a contractile phenotype to a synthetic one.7 Patients with POP also showed an increased MMP-3 and TIMP1 expression to remodel the excess of ECM as we also found in this study.27–31 The crucial role of connective tissue in the disorder is now certain, although the primitive effector of the collagen activation and deposition is still unclear.

According to literature, other factors are involved in both normal and pathological ECM remodeling also in the pelvic floor. It is known that AGEs are products of non-enzymatic glycation and oxidation of proteins and lipids, and they show a wide range of cellular and tissue effects implicated in the development and progression of several disorders (neurodegeneration, inflammation, collagen metabolism, and ECM modification).

In particular, in pelvic organ prolapse, it has been demonstrated that AGEs are overexpressed and inversely related to collagen I content.15 Recent in vitro studies on fibroblasts from the vaginal wall of patients with POP demonstrated the crucial role of AGEs on the AGE and RAGE signaling pathways. In particular, in POP, AGEs inhibited human vaginal fibroblasts and decreased the expression of collagen I through RAGE.16

Besides, in other organs, AGE could mediate MMPs’ induction through ERK1/2.32 This protein kinase causes the MMPs’ accumulation either directly or indirectly by Smads activation.20 The Smad-2/3 phosphorylation leads them to bind with the common mediator Smad4 and the Smad-2/3–Smad4 complex translocates into the nucleus, where it regulates specific genes involved in abnormal production and deposition of ECM proteins in many organs.33 This signaling is negatively regulated by inhibitory Smad-7.

As in our previous study, in which histomorphological evaluations showed an evident remodeling of muscularis propria and an increase of MMPs, TIMP, and Type III collagen in POP patients,7 we have planned to evaluate if this upregulation could depend on AGEs’ overexpression involving ERK1/2 and Smads pathway.

Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated a significant increase of expression for AGEs, ERK1/2, p-ERK in POP samples, when compared with controls, and the immunolocalization was peculiar, encircling muscle cell fibers. We observed an enhancement in Smad-7 expression in controls, consistent with the inhibitory function of this protein against Smad-2 and Smad-3. Further validations of our hypothesis came from the evaluation of TGF-β/Smads cascade as immunostaining analysis detected a noticeable positivity for Smad-2/3 and p-Smad3 in pathological samples, but they gave evidence of a reduced expression of TGF-β. These results may suggest not only a plausible role for AGEs as effectors of the connective damage, but also that their stimulation on ERK1/2 may recruit Smad-2/3 proteins without involving TGF-β.

In light of these results, we hypothesize the possible interaction between this MAPK, originally stimulated by AGEs, and Smads; this condition leads to, on one hand, an increase in MMPs’ synthesis, and, on the other hand, an increase in collagen III deposition. Both these effects represent two complementary sides of the same coin: connective tissue remodeling. This study could suggest the role of AGEs in the process of ECM homeostasis and its influence on the pathophysiology and progression of POP. These preliminary experimental observations encourage the idea that AGEs, together with ERK1/2 and Smads-2/3, might be considered as a possible pharmacological target to be employed in a therapeutic approach combined with surgery.

However, more patients will need to be enrolled to further clarify the relationship between AGE and the disarrangement of muscularis propria of the vaginal wall in POP disease.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, JHC772798_Supplemental_Material for Immunolocalization of Advanced Glycation End Products, Mitogen Activated Protein Kinases, and Transforming Growth Factor-β/Smads in Pelvic Organ Prolapse by Antonella Vetuschi, Simona Pompili, Anna Gallone, Angela D’Alfonso, Maria Gabriella Carbone, Gaspare Carta, Claudio Festuccia, Eugenio Gaudio, Alessandro Colapietro and Roberta Sferra in Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: All authors have contributed to this article as follows: AV and SP developed the study design, coordination, and manuscript drafting; SP and AG performed immunohistochemical and quantitative analyses; AC and CF were responsible for in vitro analyses; GC, ADA, and MGC provided surgical specimens; RS and EG provided study supervision, as well as critical manuscript revision; and all authors have read and approved the manuscript as submitted.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by grant RIA (Rilevante Interesse di Ateneo) from the University of L’Aquila, Department of Biotechnological and Applied Clinical Sciences, L’Aquila, Italy.

Contributor Information

Antonella Vetuschi, Department of Biotechnological and Applied Clinical Sciences, University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy.

Simona Pompili, Department of Biotechnological and Applied Clinical Sciences, University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy.

Anna Gallone, Department of Biotechnological and Applied Clinical Sciences, University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy.

Angela D’Alfonso, Department of Life, Health and Environmental Sciences, Gynecology and Obstetrics Unit, University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy.

Maria Gabriella Carbone, Department of Life, Health and Environmental Sciences, Gynecology and Obstetrics Unit, University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy.

Gaspare Carta, Department of Life, Health and Environmental Sciences, Gynecology and Obstetrics Unit, University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy.

Claudio Festuccia, Department of Biotechnological and Applied Clinical Sciences, University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy.

Eugenio Gaudio, Department of Anatomical, Histological, Forensic Medicine and Orthopedic Sciences, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy.

Alessandro Colapietro, Department of Biotechnological and Applied Clinical Sciences, University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy.

Roberta Sferra, Department of Biotechnological and Applied Clinical Sciences, University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy.

Literature Cited

- 1. Dieter AA, Wilkins MF, Wu JM. Epidemiological trends and future care needs for pelvic floor disorders. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;27:380–84. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Toozs-Hobson P, Freeman R, Barber M, Maher C, Haylen B, Athanasiou S, Swift S, Whitmore K, Ghoniem G, de Ridder D. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for reporting outcomes of surgical procedures for pelvic organ prolapse. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:415–21. doi 10.1002/nau.22238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Slieker-ten Hove MC, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Eijkemans MJ, Steegers-Theunissen RP, Burger CW, Vierhout ME. Prediction model and prognostic index to estimate clinically relevant pelvic organ prolapse in a general female population. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:1013–21. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0903-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. von Theobald P. Place of mesh in vaginal surgery, including its removal and revision. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;25:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Petros P, Swash M, Kakulas B. Experimental Study No. 8: stress urinary incontinence results from muscle weakness and ligamentous laxity in the pelvic floor. Pelviperineology. 2008;27:107–109. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Petros P, Swash M. A musculo-elastic theory of anorectal function and dysfunction in the female. Pelviperineology. 2008;27:86–87. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vetuschi A, D’Alfonso A, Sferra R, Zanelli D, Pompili S, Patacchiola F, Gaudio E, Carta G. Changes in muscularis propria of anterior vaginal wall in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Eur J Histochem. 2016;60(1):2604. doi: 10.4081/ejh.2016.2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kerkoff MH, Ruiz-Zapta AM, Bril H, Bleeker MCG, Belien JAM, Stoop R, Helder MN. Changes in tissue composition of the vaginal wall of premenopausal women with prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(2):168.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.10.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Freitas-Rodríguez S, Folgueras AR, López-Otín C. The role of matrix metalloproteinases in aging: tissue remodeling and beyond. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1864(11 Pt A):2015–2025. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nagase H, Woessner JF., Jr. Matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21491–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ramasamy R, Yan SF, Schmidt AM. Advanced glycation endproducts: from precursors to RAGE: round and round we go. Amino Acids. 2012;42:1151–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yamagishi S, Fukami K, Maatsui T. Evaluation of tissue accumulation levels of advanced glycation end products by skin autofluorescence: a novel marker of vascular complications in high-risk patients for cardiovascular disease. Int J Cardiol. 2015;185:263–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hu H, Jiang H, Ren H, Hu X, Wang X, Han C. AGEs and chronic subclinical inflammation in diabetes: disorders of immune system. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2015;31:127–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lohwasser C, Neureiter D, Weigle B, Kirchner T, Schuppan D. The receptor for advanced glycation end products is highly expressed in the skin and upregulated by advanced glycation end products and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126(2):291–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen Y, Huang J, Hu C, Hua K. Relationship of advanced glycation end products and their receptor to pelvic organ prolapse. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:2288–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen Y, Wang X, Feng W, Hua K. Advanced glycation end products decrease collagen I levels in fibroblasts from the vaginal wall of patients with POP via the RAGE, MAPK and NF-kB pathways. Int J Mol Med. 2017;40(4):987–98. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang F, Banker G, Liu X, Suwanabol PA, Lengfeld J, Yamanouchi D, Kent KC, Liu B. The novel function of advanced glycation end products in regulation of MMP-9 production. J Surg Res. 2011;171(2):871–6. 10.1016/j.jss.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li R, Lan HY, Chung ACK. Distinct roles of Smads and microRNAs in TGF-β signaling during kidney diseases. Hong Kong J Nephr. 2013;15:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.hkjn.2013.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Budi EH, Duan D, Derynck R. Transforming growth factor-β receptors and Smads: regulatory complexity and functional versatility. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27(9):658–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li JH, Huang XR, Zhu HJ, Oldfield M, Cooper M, Truong LD, Johnson RJ, Lan HY. Advanced glycation end products activate Smad signaling via TGF-β-dependent and independent mechanisms: implications for diabetic renal and vascular disease. FASEB J. 2004;18(1):176–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1117fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Meijerink AM, van Rijssel RH, van der Linden PJQ. Tissue composition of the vaginal wall in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2013;75:21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Varghese F, Bukhari AB, Malhotra R, De A. IHC profiler: an open source plugin for the quantitative evaluation and automated scoring of immunohistochemistry images of human tissue samples. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kannan K, McConnel A, McLeod M, Rane A. Microscopic alterations of vaginal tissue in women with pelvic organ prolapse. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;31:250–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. de Landsheere L, Blacher S, Munaut C, Nusjens B, Robod C, Noel A, Foidart JM, Cosson M, Nisolle M. Changes in elastin density in different locations of the vaginal wall in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:1673–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Takacs P, Gualtiere M, Nassiri M, Candiotti K, Medina C. Vaginal smooth muscle cell apoptosis is increased in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1559–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Boreham MK, Wai CY, Miller RT, Schaffer JI, Word RA. Morphometric properties of the posterior vaginal wall in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:1501–8; discussion 1508–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alarab M, Kufaishi H, Lye S, Drutz H, Shynlova O. Expression of extracellular matrix-remodeling proteins is altered in vaginal tissue of premenopausal women with severe pelvic organ prolapse. Reprod Sci. 2014;21:704–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dviri M, Leron E, Dreiher J, Mazor M, Shaco-Levy R. Increased matrix metalloproteinases-1,-9 in the uterosacral ligaments and vaginal tissue from women with pelvic organ prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;156:113–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liang CC, Huang HY, Tseng LH, Chang SD, Lo TS, Lee CL. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1, TIMP-2 and TIMP-3) in women with uterine prolapse but without urinary incontinence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;153:94–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mosier E, Lin VI, Zimmern P. Extracellular matrix expression of human prolapsed vaginal wall. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:582–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shapiro SD. Matrix metalloproteinase degradation of extracellular matrix: biological consequences. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:602–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Xu Z, Sun J, Tong Q, Lin Q, Qian L, Park Y, Zheng Y. The role of ERK1/2 in the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(12):E2001. doi: 10.3390/ijms17122001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Latella G, Vetuschi A, Sferra R, Speca S, Gaudio E. Localization of αvβ6 integrin-TGF-β1/Smad3, mTOR and PPARγ in experimental colorectal fibrosis. Eur J Histochem. 2013;57(4):e40. doi: 10.4081/ejh.2013.e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, JHC772798_Supplemental_Material for Immunolocalization of Advanced Glycation End Products, Mitogen Activated Protein Kinases, and Transforming Growth Factor-β/Smads in Pelvic Organ Prolapse by Antonella Vetuschi, Simona Pompili, Anna Gallone, Angela D’Alfonso, Maria Gabriella Carbone, Gaspare Carta, Claudio Festuccia, Eugenio Gaudio, Alessandro Colapietro and Roberta Sferra in Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry