Abstract

Background:

Bayes' theorem describes the probability of an event, based on conditions that might be related to the event.[1] We developed the Bayesian Diagnostic Gains (BDG) method as a simple tool for interpreting diagnostic impact.[2,3,4,5,6,7]

Aim:

We aimed to evaluate the clinical diagnostic impact of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) compared to traditional abdominal computed tomography (CT) and standard ultrasound (US) in a Bayesian Clinical Decision Scheme.

Materials and Methods:

Our mathematical method uses Bayesian Diagnostic Gains (BDG) model. For the purposes of our model, the EMTRAS was used as pretest probability and stratified as low risk (0–3 points = 10%), moderate risk (4–6 points = 42%), and high risk (7–12 points = 80%) based on mortality risk. Sensitivity and specificity for US, CT, and CEUS were obtained from pooled data and used to calculate LR- and LR+. Bayesian/Fagan nomogram was used to attain posttest probabilities using baseline probability of an event on the first axis (PRE), with LR on the second axis, and read off the pos-test probability (POST) on the third axis. For the nomogram analysis, the pretest probability (Pre) scoring for the EMTRAS score was obtained using the original EMTRAS data. Posttest probabilities were obtained based on the Bayes/Fagan Nomgram. Relative diagnostic gain (RDG) and absolute diagnostic gain (ADG) were calculated based on the differences deducted from pre- and post-test probabilities. IBM® SPSS® Statistics 20 was used for analysis and modeling. ANOVA was used for association between EMTRAS, CT scan, and CEUS, where P value set at 0.05.

Results:

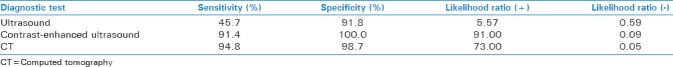

Pooled data for Sensitivity (Se), Specificity (Sp), LR+, and LR- were obtained for US (Se = 45.7%, Sp = 91.8%, LR+ = 5.57, and LR- = 0.59), CEUS (Se 91.4%, Sp 100%, LR+ 91, and LR-0.09), and CT (Se = 94.8%, SP = 98.7%, LR+ = 73, and LR- =0.05). ANOVA analysis for LR+ and LR- showed no significant difference (P < 0.8745 and P < 0.9841). Comparison of CT and CEUS did not yield statistically significant differences for LR+ (P < 0.1).

Conclusion:

In this Bayesian model, the diagnostic performance of CEUS was found to be similar to traditional abdominal CT. The greatest diagnostic gain was observed in low pretest positive LR groups.

Key Words: Contrast enhanced, trauma, ultrasound

INTRODUCTION

In probability theory and statistics, Bayes' theorem describes the probability of an event, based on conditions that might be related to the event Bayes' theorem then links the degree of belief in a proposition before (pretest probability) and after (posttest probability) accounting for evidence.[1]

With the Bayesian probability interpretation, the theorem expresses how a subjective degree of belief should rationally change to account for evidence: this is Bayesian inference, which is fundamental to Bayesian statistics. The Fagan/Bayesian nomogram is a graphical calculator that is a useful and convenient way to perform calculations without the need to remember the formula integrating pretest probability with diagnostic tests and likelihood ratios (LRs) [Figures 1–3]. The use of the Fagan/Bayes' nomogram has simplified the use of diagnostic test information and is now frequently used by numerous physicians. We developed the Bayesian Diagnostic Gains (BDG) method as a simple clinical tool for interpreting diagnostic impact, this mathematical decision support model has been studies and validated by our ACDC work group.[2,3,4,5,6,7]

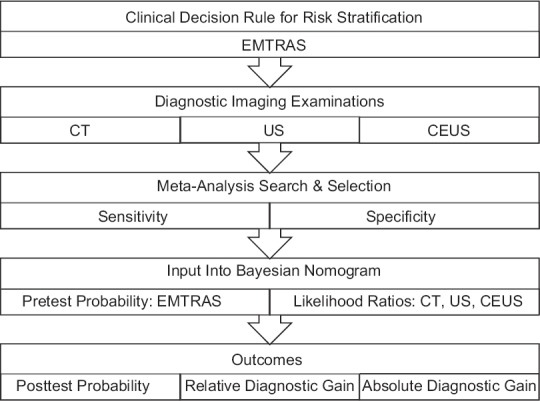

Figure 1.

Methodology schematic

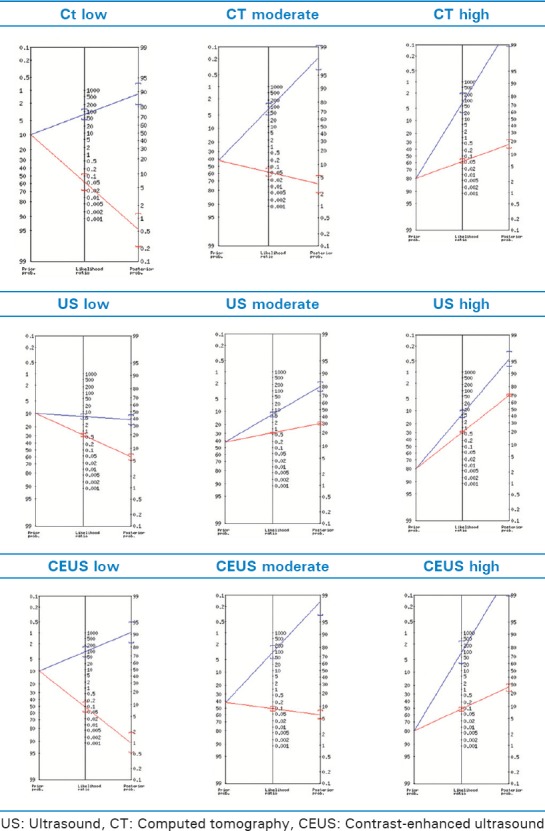

Figure 3.

Bayesian/Fagan nomograms for computed tomography, ultrasound, and contrast-enhanced ultrasound

The Emergency Trauma Score (EMTRAS) was developed to be an easy-to-compute scoring system for the emergency resuscitation and based on a limited number of clinical predictors that are commonly and early available. In 2009, Raum et al.[8] introduced the EMTRAS for early estimation of mortality risk in adult trauma patients. EMTRAS combines four early predictors from the emergency resuscitation room and demonstrated favorable discrimination compared with more complex scores. The early predictors used by EMTRAS are age (year), Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), base excess (mmol/L), and prothrombin time (PT) (%). For each predictor, a sub score of 0, 1, 2, or 3 points is assigned, based on the actual value of the predictor. EMTRAS is defined as the sum of these sub scores, that is, the lowest (best) EMTRAS is zero and the highest (worst) is 12. The EMTRAS was developed in a large cohort (n = 4808) of trauma patients with an Injury Severity Score[8] of 16 or higher and derived from the German Trauma Registry (http://www.traumaregister.de). The EMTRAS has been internally and externally validated.[8,9] Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the clinical diagnostic impact of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) compared to traditional abdominal computed tomography (CT) and standard ultrasound (US) in a Bayesian Clinical Decision Scheme integrating the EMTRAS.

METHODS

Mathematical model

Sensitivity was defined as the ability of a test to correctly identify those with the disease (true positive rate), whereas test specificity was defined as the ability of the test to correctly identify those without the disease (true negative rate). LRs were used as epidemiological instruments to show how much we should shift our suspicion for a particular test result. The positive LR (LR+) was defined as probability of an individual with the condition having a positive test LR+ = probability of an individual without the condition having a positive test. Similarly, the negative LR (LR−) was defined as probability of an individual with the condition having a negative test LR− = probability of an individual without the condition having a negative test. We defined LR+ and LR− in terms of sensitivity and specificity:

LR+ = sensitivity / (1-specificity) = (a/(a+c)) / (b/(b+d))

LR- = (1-sensitivity) / specificity = (c/(a+c)) / (d/(b+d))

Specificity

Bayes' theorem was used to convert the results from CT, US, and CEUS testing into the probability of the event. Bayes' math describes the analysis as a relation of Pr (AǀX), the chance that an event A happened given the indicator X, and Pr (XǀA), the chance the indicator X happened given that event A occurred. Our mathematical method uses Bayes' nomogram [Figures 1–3]. In statistics, a nomogram is an arrangement of two linear or logarithmic scales such that an intersecting straight line enables an intermediate values or values on a third scale to be read off using a straight edge on the nomogram, line up the baseline probability of an event on the first axis, with LR on the second axis, and read off the posttest probability on the third axis [Figure 1].

Population

Stratification of the population was made using point scores attributed by applying the EMTRAS which is comprised four parameters: patient age, GCS, base excess, and PT. For the purposes of our model, the EMTRAS was used as pretest probability and stratified as low risk (0–3 points = 10%), moderate risk (4–6 points = 42%), and high risk (7–12 points = 80%) based on mortality risk. Sensitivity and specificity for US, CT, and CEUS were obtained from pooled data and used to calculate LR− and LR+ [Figure 1].[10,11,12,13]

Outcomes

Bayesian nomogram was used to attain posttest probabilities using baseline probability of an event on the first axis (PRE), with LR on the second axis, and read off the posttest probability (POST) on the third axis. For the nomogram analysis, the pretest probability (Pre) scoring for the EMTRAS score was obtained using the original EMTRAS data.

Posttest probabilities were obtained after inserting EMTRAS score as pretest probability and LRs into Bayesian nomogram [Tables 1–4]. Posterior probability is the mathematical sum of the diagnostic value of the EMTRAS plus CEUS or CT scan.

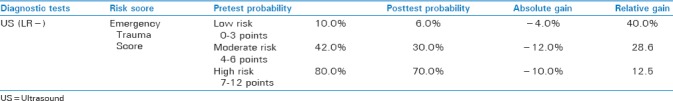

Table 1.

Diagnostic gain results for ultrasound

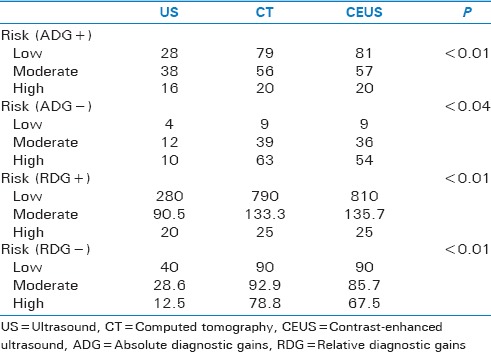

Table 4.

Stuart-Maxwell test results for absolute diagnostic gains and relative diagnostic gains in “rule ins (+) and rule outs (−)”

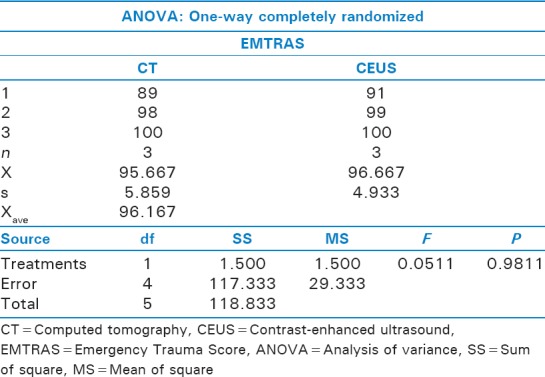

We developed a simple method for interpreting diagnostic impact, where relative diagnostic gain (RDG) and absolute diagnostic gain (ADG) were calculated based on the differences deducted from pre- and posttest probabilities (ADG = post-test – pre-test) and (RDG = 100 × post-test – pre-test/Pre-test).[2,3,4,5,6,7] Figure 2 reflects an example of the mathematical model for creating the case distribution and calculations. IBM® SPSS® Statistics 20 was (IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY, USA) used for analysis and modeling. ANOVA was used to evaluate strength of association between EMTRAS, CT scan, and CEUS, and Stuart–Maxwell test was used for symmetry and marginal homogeneity testing, where P value set at 0.05. IBM® SPSS® Statistics 20 was used for analysis and modeling. The mathematical nature of this study makes it Institutional Review Board exempt.

Figure 2.

Analysis of variance between computed tomography and contrast-enhanced ultrasound

RESULTS

Pooled data for Sensitivity (Se), Specificity (Sp), LR+, and LR− were obtained [Table 5] for US (Se = 45.7%, Sp = 91.8%, LR+ = 5.57, and LR− = 0.59), CEUS (Se 91.4%, Sp 100%, LR+ 91, and LR− 0.09), and CT (Se = 94.8%, SP = 98.7%, LR+ = 73, and LR− = 0.05).[12]

Table 5.

Sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios

US LR+ model results showed low-risk posttest probability of 38%, RDG of 28%, and ADG of 280%, moderate-risk posttest of 80%, RDG of 38%, and ADG of 90.5%, whereas high-risk posttest of 96%, RDG of 16%, and ADG of 20% [Table 1].

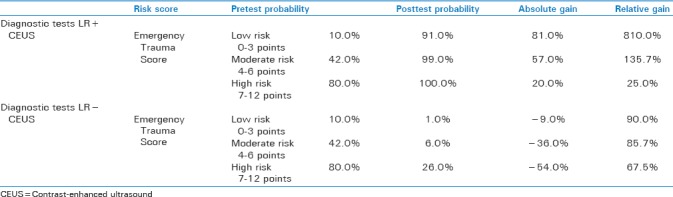

Contrast-enhanced US model results for LR + yielded low-risk posttest probability of 91%, ADG of 81.0%, and RDG of 810.0%, moderate-risk posttest probability of 99.0%, ADG of 57.0%, and RDG of 135.7%, whereas high-risk posttest probability of 100.0%, RDG of 20.0%, and RDG of 25.0% [Table 2].

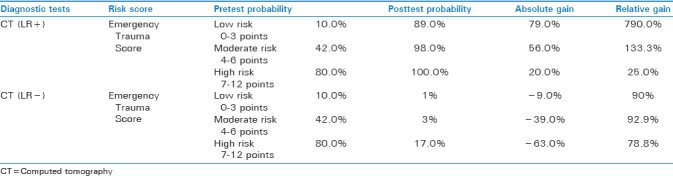

Table 2.

Diagnostic gain results for computed tomography for positive and negative likelihood rations

CT LR+ results were low-risk posttest of 89%, RDG of 79%, and ADG of 790%, moderate-risk posttest of 98%, RDG of 56%, and ADG of 133.3%, whereas high-risk scores, posttest of 100%, RDG of 20%, and ADG of 25% [Table 3].

Table 3.

Diagnostic gains analysis for contrast-enhanced ultrasound

ANOVA analysis for LR+ showed no significant difference (P < 0.8745), with standard error of difference of 485.39 [Figure 1]. ANOVA analysis for LR− showed no significant difference (P < 0.9841), with standard error of difference of 248.123. Comparison of CT and CEUS did not yield statistically significant differences for LR+ (P < 0.1) [Figure 2].

Stuart–Maxwell test comparing ADG for LR+ P yielded a P < 0.0001 and ADG for LR− a P < 0.04, when comparing RDG for LR+ a P < 0.0001 0001 and RDG for LR− a P < 0.0001 [Table 4].

DISCUSSION

This study using Bayesian statistical model demonstrated the comparable diagnostic quality of CEUS and CT scan in risk-stratified patients using EMTRAS score. More specifically, for rule out of disease, CT and CEUS were statistically significantly superior than traditional US in all three risk populations, proving that clinically, CEUS has equal diagnostic accuracy to discard disease in all patient populations. Lowest diagnostic gain was observed using traditional US, where ADG ranged from 12.5% to 40%, lowest being high pretest probability population. Our results showed greatest ADG (81.0%) for low pretest probability EMTRAS using CEUS.

Previously published literature also provides evidence of the superiority of CT and CEUS over simple abdominal US.[8,9,10,11,12,13,14] More specifically, Catalano et al.[14] evaluated concordance of results among US and CEUS in patients with blunt abdominal trauma, showing an increase in sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy when using CEUS. In our moderate-risk patient population, however, CT scan demonstrated a superior RDG in ruling out disease.

These results are important in that they suggest that moderate-risk individuals represent the most beneficial population in being imaged to rule out disease severity using EMTRAS and CT scan. Likewise, Pinto et al.[15] reported that CEUS can provide a more reliable evaluation of solid organ injuries and vascular-related complications in a more timely manner yet concluded that it does not replace CT imaging. Our results showcase promising potential applications for austere and resource-limited environments.

Limitations of this study include the mathematical nature of this model as well as the use of pooled meta-analysis data for diagnostic performance indicators. Other limitations include those related to severity of injury speculations based on the use EMTRAS score. Furthermore, future studies should take into consideration the cost of a CEUS or CT test when choosing appropriateness of test, as by choosing the correct test for the right patient, one could save an important amount of dollars per patient. A more comprehensive value-based and cost-effective analysis will be performed in a future study. Other further implications in potential future studies that we recommend involve the implications of contrast-enhanced risks of CEUS versus the radiation-related risks posed by CT scan, which would be particularly beneficial in the pediatric population.

CONCLUSION

In a Bayesian Clinical Decision Scheme incorporating EMTRAS for risk stratification, the diagnostic performance of CEUS was found to be similar to traditional abdominal CT. The greatest diagnostic gain was observed in low pretest positive LR groups, and further validation of this model is needed as well as cost-benefit analysis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Medow MA, Lucey CR. A qualitative approach to bayes' theorem. Evid Based Med. 2011;16:163–7. doi: 10.1136/ebm-2011-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baez AA, Cochon L. Acute care diagnostics collaboration: Assessment of a bayesian clinical decision model integrating the prehospital sepsis score and point-of-care lactate. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:193–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baez AA, Cochon L. Improved rule-out diagnostic gain with a combined aortic dissection detection risk score and D-dimer bayesian decision support scheme. J Crit Care. 2017;37:56–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cochon L, Esin J, Baez AA. Bayesian comparative model of CT scan and ultrasonography in the assessment of acute appendicitis: Results from the acute care diagnostic collaboration project. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:2070–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cochon L, McIntyre K, Nicolás JM, Baez AA. Incremental diagnostic quality gain of CTA over V/Q scan in the assessment of pulmonary embolism by means of a wells score bayesian model: Results from the ACDC collaboration. Emerg Radiol. 2017;24:355–9. doi: 10.1007/s10140-017-1486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cochon L, Smith J, Baez AA. Bayesian comparative assessment of diagnostic accuracy of low-dose CT scan and ultrasonography in the diagnosis of urolithiasis after the application of the STONE score. Emerg Radiol. 2017;24:177–82. doi: 10.1007/s10140-016-1471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cochon L, Ovalle A, Nicolás JM, Baez AA. Acute care diagnostic collaboration: Bayesian modeling comparative diagnostic assessment of lactate, procalcitonin and CRP in risk stratified population by mortality in ED (MEDS) score. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35:564–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raum MR, Nijsten MW, Vogelzang M, Schuring F, Lefering R, Bouillon B, et al. Emergency trauma score: An instrument for early estimation of trauma severity. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1972–7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819fe96a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soto JA, Anderson SW. Multidetector CT of blunt abdominal trauma. Radiology. 2012;265:678–93. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laugesen NG, Nolsoe CP, Rosenberg J. Clinical applications of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the pediatric work-up of focal liver lesions and blunt abdominal trauma: A Systematic review. Ultrasound Int Open. 2017;3:E2–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-124502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao DW, Tian M, Zhang LT, Li T, Bi J, He JY, et al. Effectiveness of contrast-enhanced ultrasound and serum liver enzyme measurement in detection and classification of blunt liver trauma. J Int Med Res. 2017;45:170–81. doi: 10.1177/0300060516678525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sessa B, Trinci M, Ianniello S, Menichini G, Galluzzo M, Miele V, et al. Blunt abdominal trauma: Role of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in the detection and staging of abdominal traumatic lesions compared to US and CE-MDCT. Radiol Med. 2015;120:180–9. doi: 10.1007/s11547-014-0425-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miele V, Piccolo CL, Galluzzo M, Ianniello S, Sessa B, Trinci M, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in blunt abdominal trauma. Br J Radiol. 2016;89:20150823. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catalano O, Aiani L, Barozzi L, Bokor D, De Marchi A, Faletti C, et al. CEUS in abdominal trauma: Multi-center study. Abdom Imaging. 2009;34:225–34. doi: 10.1007/s00261-008-9452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinto F, Valentino M, Romanini L, Basilico R, Miele V. The role of CEUS in the assessment of haemodynamically stable patients with blunt abdominal trauma. Radiol Med. 2015;120:3–11. doi: 10.1007/s11547-014-0455-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]