Abstract

New regulations require living kidney donor (LKD) follow-up for two years, but donor retention remains poor. Electronic communication (e.g. text messaging, e-mail) might improve donor retention. To explore the possible impact of electronic communication, we recruited LKDs to participate in an exploratory study of communication via telephone, e-mail, or text messaging post-donation; communication through this study was purely optional and did not replace standard follow-up. Of 69 LKDs recruited, 3% requested telephone call, 52% e-mail, and 45% text messaging. Telephone response rate was 0%; these LKDs were subsequently excluded from analysis. Overall response rates with email or text messaging at 1-week, 1-month, 6-months, 1-year, and 2-years were 94%, 87%, 81%, 72%, and 72%. Lower response rates were seen in African Americans, even after adjusting for age, sex, and contact method (incidence rate ratio (IRR) nonresponse 2.075.8116.36, p=0.001). Text messaging had higher response rates than email (incidence rate ratio (IRR) nonresponse 0.110.280.71, p=0.007). Rates of nonresponse were similar by sex (incidence rate ratio (IRR) 0.68, p=0.4) and age (incidence rate ratio (IRR) 1.00, p>0.9). In summary, LKDs strongly preferred electronic messaging over telephone and were highly responsive two years post-donation, even in this non-required, non-incentivized exploratory research study. These electronic communication tools can be automated and may improve regulatory compliance and post-donation care.

Keywords: living kidney donor, electronic messaging, communication, follow-up

INTRODUCTION

Since 1999, the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) has collected follow-up data on living donors.1 However, rates of follow-up have been poor despite a majority of living donors believing that follow-up should extend at least two years and that achieving this is a high priority.2 From 2008–2012, clinical follow-up data were reported for only 67% of LKDs at six months and 50% at two years post-donation, while laboratory follow-up data were reported for only 51% and 30% at 6 months and 2 years, respectively.3 In 2013, UNOS began to require that donor follow-up meet specific thresholds. For example, for anyone who donated after December 31, 2014, 80% must have complete clinical data and 70% must have complete laboratory data.4,5 In the first cohort of donors under this new policy, less than 50% of centers were compliant with donor follow-up at the specified thresholds.6 Without new strategies for improving follow-up, it will be difficult for centers to meet these thresholds.

The traditional approach to follow-up, including clinic visits, telephone calls, and paper mailings, is resource-intensive and cumbersome for both patient and provider. Methods of follow-up communication that are realistic for transplant centers and donors must be efficient and effective. Technologies such as automated text messages and e-mail provide potential novel avenues to contact donors for follow-up. These electronic messaging systems are now nearly ubiquitous in our society; a Pew Research Center Survey found that 90% of adults in the United States had a mobile phone as of January 2014.7 While many individuals remain too technophobic to communicate via “apps” or social media, nearly all individuals communicate electronically in some manner or another. Email and text messaging provide an opportunity to bring providers to the patient in a convenient manner.

National transplant organizations have recommended the use of these technologies; the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) “Procedures to collect post-donation follow-up data from living donors” recommends that providers “use not only regular mail and telephone contacts, but emails and texts to communicate with donors.” However, despite promising results in other clinical fields,8–10 these technologies have not yet been studied in the LKD population. We hypothesized that electronic follow-up methods, including automated text messaging, email, and telephone calls, would improve donor follow-up rates following donation. To investigate this hypothesis, we performed an exploratory prospective study of electronic communication with LKDs at our center.

METHODS

Study population

LKDs who underwent living kidney donation at our institution between May 2010 and June 2011 were approached during their one week follow-up appointment and offered to participate in a pilot study of communication by the institution via text messaging, e-mail, or telephone call; participants represented a convenience sample of LKDs at our center. Participants were informed that the study communication would not replace regular follow-up, but was just for exploring feasibility and retention. LKDs who chose to participate selected their preferred method of communication and were contacted at 1 week, 1 month, 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after initial enrollment. Due to a response rate of 0%, LKDs who resided internationally (5%, N=4) were excluded from further analysis. This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board.

This study used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The SRTR data system includes data on all donor, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the US, submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), and has been described elsewhere.11 The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors.

Electronic communication

LKDs were given the phone number and e-mail address associated with a dedicated e-mail account that would be used to contact them. They were asked to add these to their contact lists so they would know the messages came from the transplant center, and to avoid spam-filtering. LKDs were contacted using their preferred communication modality (text, e-mail, or phone call) at 1 week, 1 month, 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after their enrollment in the study. These messages were sent out by an automated system, and the content of the messages was standardized. Participants who did not respond were sent additional messages. If participants failed to respond to text message or email three times, a research assistant called them to confirm that the contact information on record was correct. Patients who selected telephone call (3%, N=2) as their primary method of contact had a response rate of 0% and were excluded from further analysis.

Comparing clinical and research response

This study was initiated prior to the February 2013 OPTN requirements, but our center was already using the OPTN-recommended follow-up intervals of 6 months, 12 months, and 2 years. Since this research study was completely separate from our clinical follow-up protocols (conducted by different individuals, with patients explicitly told that response in this study did not “count” as follow-up by the clinical team), we compared aggregate rates of successful follow-up at our center through our standard clinical protocols (as reported to OPTN) during this time period with aggregate follow-up in this research study. Since some of our study participants had a 2-year follow-up visit after the implementation of new OPTN follow-up requirements, we also analyzed patients stratified by whether their follow-up was completed before or after new follow-up requirements were implemented.

Statistical analysis

We defined response rate as the percentage of total participants who responded to the text message, email, or phone call that they received at a particular time point as a part of this study. The proportion of participants who responded, by demographic characteristics, was compared using Fisher’s exact testing. Univariate analysis was used to explore associations between rates of nonresponse and race, sex, age, contact method, in-state versus out-of-state residence, and donor-recipient relationship type. For state of residence and donor-recipient relationship, no significant relationship was found with rate of nonresponse on univariate or multivariate analysis, and these variables were excluded from the final multivariable models. To determine demographic characteristics associated with nonresponse, we estimated the association between LKD characteristics and rate of nonresponse at each time point using a patient-level modified Poisson regression model including sex, race, age, and contact method.

We estimated the incidence rate ratio (IRR) of nonresponse at the follow-up time points using a multi-level Poisson regression model with a random intercept at each follow-up time point, adjusted for donor characteristics including age at donation, sex, race, and contact mode. We tested potential non-linearity of the effect of age using a LOWESS plot, and there was no statistically significant deviation from the linearity assumption.

To assess absolute differences in rate of nonresponse, we created a predictive model of the rate of nonresponse to show the absolute change in nonresponse over time for a reference patient. This model included age at donation, race, sex, and contact method. We selected a reference patient who was African American, female, and 45 years old who was contacted via text message. We then used the model to predict the probability of nonresponse at each time period in the study (1 week, 1 month, 6 months, 1 year, 2 years) for our reference patient.

Confidence intervals are reported using subscripts, as per the method of Louis and Zeger.12 All analyses were performed using Stata 14.1/MP for Windows (College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Study population

Between May 2010 and June 2011, 67 LKDs who underwent nephrectomy at our center participated in this study. Of study participants, 55% were female and 20.9% were African American. The median LKD age at donation was 45 years (IQR 33–53, range 19–74) (Table 1). By comparison, the overall population of domestically-residing LKDs at the Johns Hopkins Hospital during the study period was 59.6% female and 18.3% African American, with a median (IQR) age of 44.5 (32–52.5) years.

Table 1. Characteristics of LKD participants, overall and by preferred communication method chosen.

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the proportion of participants who used email versus text messaging, by demographic characteristics. No significant differences were seen in the proportion of patients selecting email versus text messaging by sex or race. However, there was a significant difference in patient selection of email versus text message by age group, with patients 31–50 years old preferring text messaging over e-mail and patients ≤30 or >50 years old preferring e-mail.

| Patient Characteristics | N | E-mail (%) | Text (%) | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Overall | 67 | 54% | 46% | 0.6 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 29 | 62% | 38% | 0.3 |

| Female | 38 | 47% | 53% | |

| Race | ||||

| African American | 14 | 29% | 71% | 0.04 |

| Other | 53 | 60% | 40% | |

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 67 | 49 (36–57.5) | 42 (32–49) | 0.1 |

| Age groups | ||||

| ≤30 years | 12 | 58% | 42% | |

| 31–40 years | 13 | 38% | 62% | |

| 41–50 years | 22 | 36% | 64% | 0.02 |

| 51–60 years | 13 | 69% | 31% | |

| >60 years | 7 | 100% | 0% | |

Methods of communication

Among participants, 52% selected e-mail and 45% selected text message as their method of communication. Text messaging was the chosen form of communication for 38% of males and 53% of females (P=0.3), and for 71% of African American donors and 40% of non-African American donors (P=0.04; Table 1). E-mail was the preferred contact method for the youngest (≤30 years old) and oldest (>50 years old) donors, while text messaging was preferred by donors 31–50 years old (p=0.02, Table 1).

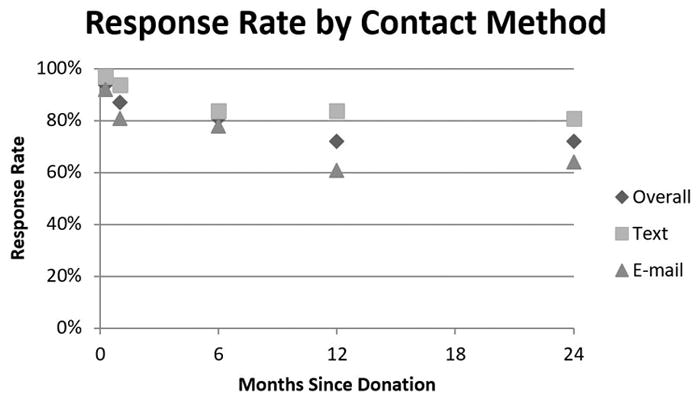

Response rates overall and by LKD characteristics

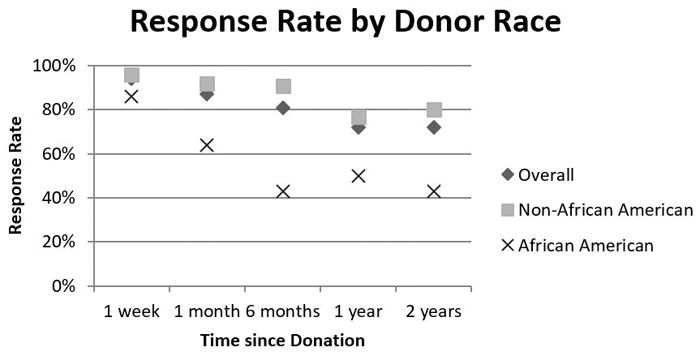

The overall response rate was 94% at 1 week, 87% at 1 month, 81% at 6 months, 72% at 1 year, and 72% at 2 years. Response rates were consistently higher for participants using text messaging versus email: 97% versus 92% at 1 week, 94% versus 81% at 1 month, 84% versus 78% at 6 months, 84% versus 61% at 1 year, and 81% versus 64% at 2 years. This trend persisted after adjusting for donor age, race, and sex (IRR of nonresponse to text messaging versus email 0.110.280.71, p=0.007; Table 3).

Table 3. Multilevel modified Poisson regression model of LKD nonresponse rate.

Multilevel modified Poisson regression showed similar rates of nonresponse among LKDs of different sex (p=0.4) and age (p>0.9). Contact via text messaging produced lower rates of nonresponse than contact via email (p=0.007). Significantly higher nonresponse rates were associated with donors of African American race (p=0.001) and later follow-up time points.

| Incidence Rate Ratio of Nonresponse | P | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Donor age, per year | 0.971.001.03 | >0.9 |

| Female sex | 0.290.681.59 | 0.4 |

| African American race | 2.075.8116.36 | 0.001 |

| Text message | 0.110.280.71 | 0.007 |

| Response over time | ||

| 1 week | (reference) | |

| 1 month | 0.692.257.31 | 0.2 |

| 6 months | 1.063.259.97 | 0.04 |

| 1 years | 1.624.7513.96 | 0.005 |

| 2 years | 1.624.7513.96 | 0.005 |

There was no significant difference in response rate by age on univariate analysis (Table 2) or after adjusting for LKD sex, race, and contact method (IRR of nonresponse per year of age 0.971.001.03, p>0.9; Table 3). There was also no significant difference in response rate by sex on univariate analysis (Table 2) or after adjusting for LKD age, race, and contact method (IRR of female versus male sex 0.290.681.59, p=0.4; Table 3). African American LKDs had significantly lower response rates at 1 month (p=0.02), 6 months (p<0.01), and 2 years (p=0.02) compared to non-African American LKDs (Table 2). While all racial groups had high initial response rates, there was a large decline in response rate among African American donors (86% at 1 week, 43% at 2 years), but only a modest decline in response rate among non-African American donors (96% at 1 week, 80% at 2 years; Table 2). After adjusting for donor age, sex, and contact method, African Americans had a lower response rate compared to donors of other races (IRR of nonresponse 2.075.8116.36, p=0.001, Table 3).

Table 2. Follow-up response rates for LKDs by subgroup.

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the proportion of participants who responded, by demographic and study characteristics. LKDs of all ages were responsive to follow-up e-mail or text messages, particularly at earlier time points. Response rates were similar by contact method, donor sex, and donor age (by decade). Lower response rates were seen in African American donors than in non-African American donors.

| N | 1 week | P | 1 month | P | 6 month | P | 1 year | P | 2 years | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 67 | 94% | 87% | 81% | 72% | 72% | |||||

| 36 | 92% | 0.6 | 81% | 0.2 | 78% | 0.8 | 61% | 0.0 | 64% | 0.2 | |

| Text | 31 | 97% | 94% | 84% | 84% | 6 | 81% | ||||

| Male | 29 | 93% | 1.0 | 90% | 0.7 | 86% | 0.4 | 69% | 0.8 | 69% | 0.8 |

| Female | 38 | 95% | 84% | 76% | 74% | 74% | |||||

| AA* Race | 14 | 86% | 0.2 | 64% | 0.02 | 43% | <0.0 | 50% | 0.1 | 43% | 0.0 |

| Other Race | 53 | 96% | 92% | 91% | 1 | 77% | 80% | 2 | |||

| Age (years): | |||||||||||

| ≤30 | 12 | 92% | 83% | 75% | 58% | 50% | |||||

| 31–40 | 13 | 92% | 85% | 85% | 69% | 69% | |||||

| 41–50 | 22 | 95% | 0.8 | 86% | 0.4 | 77% | 0.7 | 73% | 0.3 | 82% | 0.2 |

| 51–60 | 13 | 100% | 100% | 92% | 92% | 85% | |||||

| >60 | 7 | 86% | 71% | 71% | 57% | 57% | |||||

AA = African American

Changes in response rate over time

Overall response rate decreased slowly at each time point observed. Using the first time point of 1 week post-enrollment as a reference, the incidence rate ratio of nonresponse was suggestive but not statistically significant at 1 month (IRR 0.692.257.31, p=0.2) and increased significantly at 6 months (IRR 1.063.259.97, p=0.04), 1 year (IRR 1.624.7513.96, p=0.005), and 2 years (IRR 1.624.7513.96, p=0.005; Table 3). In absolute terms, the predicted probability of nonresponse for a reference patient was 0%5%11% at 1 week, 6%13%20% at 1 month, 11%19%27% at 6 months, 18%28%38% at 1 year, and 18%28%38% at 2 years.

Clinical versus research follow-up

In our clinical practice, during the study time period, the rates of overall complete follow-up were 11.9% at 6 months, 12.8% at 1 year, and 20.2% at 2 years, compared to 81%, 72%, and 72% research follow-up for the electronic communication study (p<0.001). For those patients whose two years of follow-up were complete prior to the implementation of new OPTN follow-up requirements, the rates of complete follow-up were 4% at 6 months, 9% at 12 months, and 13% at 2 years (compared to 77%, 69%, and 67% research follow-up, all p<0.001). For those patients whose two years of follow-up were completed after the implementation of new OPTN follow-up requirements, the rates of complete follow-up were 25% at 6 months, 20% at 12 months, and 33% at 2 years (compared to 89%, 79%, and 84% research follow-up, all p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

In this single-center exploratory study of electronic communication tools for living donor follow-up, we found that over 97% of LKD participants selected e-mail or text messaging as their preferred method of contact. Of patients who chose one of these two modalities, the response rate was 94% at 1 week, 87% at 1 month, 81% at 6 months, 72% at 1 year, and 72% at 2 years post-donation, significantly higher than our own clinical follow-up reporting to the OPTN (p<0.001). Lower response rates were independently associated with African American race (IRR of nonresponse 2.075.8116.36, p=0.001); higher response rates were associated with the use of text message versus email (IRR of nonresponse 0.110.280.71, p=0.007). No change in response rate was observed by sex (IRR of nonresponse 0.290.681.59, p=0.4) or age (IRR of nonresponse per year 0.971.001.03, p>0.9).

The response rates in our study are higher than published national follow-up rates at 6 months and 1 and 2 years of 67%, 60%, and 50% for clinical data and 51%, 40%, and 30% for laboratory data.3 These reported national follow-up rates are below compliance thresholds for current OPTN guidelines.13 While the different time periods, sample sizes, and type of information obtained from patients limit the comparison of our data to that used by Schold et al., the higher rates of response to electronic research communication than rates of standard clinical follow-up at our own center suggest that electronic supplementation for follow-up would likely help clinicians maintain contact with patients who might otherwise be lost to follow-up.

While our 72% study response rate at 2 years is encouraging and far exceeds current OPTN reporting, we noted lower response rates among African American LKDs. This is consistent with previous studies that found lower rates of follow-up among African American donors.3 However, previous studies of electronic messaging in clinical settings have found that text messaging and email reminders were particularly useful in African American patients.8 Therefore, though we found that African American donors had a lower absolute response rate than donors of other races, we believe that electronic messaging still has potential to increase follow-up rates in this group. Strategies to improve follow-up in African American donors are of particular importance given their higher risk for complications including end-stage renal disease compared to donors of other races.14 Further optimization of our strategy might benefit these at-risk groups.

Limitations of this study include a small sample size, which may obscure subtle relationships in how response rate changes with age and over time. Nevertheless, significant associations between response rate and LKD characteristics were seen. Furthermore, our study was limited to simple, non-required, non-incentivized communication that did not replace required follow-up, so motivation to participate and respond was likely lower than it would be in a true clinical setting; in other words, in a clinical setting where response was required and even possibly incentivized, response rates at 2 years might approach closer to 100%.

Improving the follow-up of LKDs is imperative, given the serious albeit rare risks associated with living donation. Utilization of electronic methods may improve retention of LKDs through cost-effective, convenient means. We found that LKDs preferred email and text message to telephone call for communication and that donor age was not a barrier to implementation of these technologies. These methods may enhance current follow-up and allow centers to better achieve OPTN targets for LKD follow-up.

Figure 1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants number R01DK096008, K01DK101677, and K24DK10182801 from the National Institute of Health (NIH). The analyses described here are the responsibility of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. JR and DS are supported by a Doris Duke Clinical Research Mentorship grant.

The data reported here have been supplied by the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation (MMRF) as the contractor for the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR or the U.S. Government.

ABBREVIATIONS

- LKD

living kidney donor

- IRR

incidence rate ratio

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS:

Jessica Ruck – data analysis and interpretation, drafting manuscript. Sheng Zhou – data analysis, drafting manuscript. Alvin Thomas – data analysis, drafting manuscript. Shannon Cramm – data analysis, drafting manuscript. Allan Massie – data analysis and interpretation, revising manuscript. John Montgomery – study design, data collection, revising manuscript. Jonathan Berger – study design, data collection, revising manuscript. Macey Henderson – data interpretation, revising manuscript. Dorry Segev – study design, data analysis and interpretation, revising manuscript.

References

- 1.Brown JRS, Higgins R, Pruett TL. The Evolution and Direction of OPTN Oversight of Live Organ Donation and Transplantation in the United States. American Journal of Transplantation. 2009;9(1):31–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waterman ADDM, Davis CL, McCabe M, Wainright JL, Forland CL, Bolton L, Cooper M. Living-donor follow-up attitudes and practices in US kidney and liver donor programs. Transplantation. 2013;95(6):883–888. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31828279fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schold JD, Buccini LD, Rodrigue JR, et al. Critical Factors Associated With Missing Follow-Up Data for Living Kidney Donors in the United States. American Journal of Transplantation. 2015;15(9):2394–2403. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Network OPaT. Policy 18.5: Living Donor Data Submission Requirements. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Network OPT. Policy 18.2: Timely Collection of Data. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henderson ML, Thomas AG, Shaffer A, et al. The National Landscape of Living Kidney Donor Follow-Up in the United States. American Journal of Transplantation. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14356. n/a-n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pew Research Center Internet Project Survey, January 9–12, 2014. N=1,006 adults.

- 8.Saeedi OLC, Ellish N, Robin A. Potential Limitations of E-mail and Text Messaging in Improving Adherence in Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension. Journal of Glaucoma. 2015;24(5):8. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song H, May A, Vaidhyanathan V, Cramer EM, Owais RW, McRoy S. A two-way text-messaging system answering health questions for low-income pregnant women. Patient Education and Counseling. 2013;92(2):182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saffari M, Ghanizadeh G, Koenig HG. Health education via mobile text messaging for glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Primary Care Diabetes. 2014;8(4):275–285. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Massie AB, Kuricka LM, Segev DL. Big Data in Organ Transplantation: Registries and Administrative Claims. American Journal of Transplantation. 2014;14(8):1723–1730. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Louis TA, Zeger SL. Effective communication of standard errors and confidence intervals. Biostatistics. 2009;(1):1–2. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxn014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Network OPaT. Procedures to collect post-donation follow-up data from living donors. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Wang M, et al. Risk of end-stage renal disease following live kidney donation. JAMA. 2014;311(6):579–586. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.285141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]