Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis is a synovial inflammatory disease marked by joint infiltration by immune cells and damage to the extracellular matrix. Although genetics plays a critical role in heritability and its pathogenesis, the relative lack of disease concordance in identical twins suggests that noncoding influences can affect risk and severity. Environmental stress, which can be reflected in the genome as altered epigenetic marks, also contributes to gene regulation and contributes to disease mechanisms. Studies on DNA methylation suggest that synovial cells, most notably fibroblast-like synoviocytes, are imprinted in rheumatoid arthritis with epigenetic marks and subsequently assume an aggressive phenotype. Even more interesting, the synoviocyte marks are not only disease specific but can vary depending on the joint of origin. Understanding the epigenetic landscape using unbiased methods can potentially identify nonobvious pathways and genes that that are responsible for synovial inflammation as well as the diversity of responses to targeted agents. The information can also be leveraged to identify novel therapeutic approaches.

INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common inflammatory arthritis and affects approximately 1% of adults worldwide (1). There are minor variations in prevalence in different populations around the world, and a few groups such as the Pima Indians in North America have a much higher rate. Nevertheless, the risk of developing RA is surprisingly constant regardless of location, ethnicity, or race. Women are affected more commonly than men with a 2.5 to 1 or 3.5 to 1 ratio, although the precise mechanism of the sex predilection is unclear. The average age of onset is between 30 and 50 years of age, but RA can occur at all stages of life. RA is typically a symmetric polyarticular arthritis affecting primarily the small joints of the hands and feet and other larger joints including the ankles, wrists, knees, elbows, and hips as it progresses. The most common clinical findings include joint tenderness and pain due to the influx of mononuclear cells, especially CD4+ T cells, into the synovial lining of the joint. The intimal lining of the joint becomes markedly hyperplastic, with an increase in macrophage-like and fibroblast-like cells that produce degradative enzymes and a wide array of inflammatory cytokines.

During the last few decades, treatment paradigms have shifted. With increasing use of methotrexate and the advent of targeted therapies, especially anticytokine therapy, long-term outcomes for RA have improved dramatically. Despite our best efforts, however, a significant percentage of patients never respond or have a clearly inadequate response to all of the available agents. Assuming that this population is approximately 10% to 20% of patients, this means that as many as 300,000 to 600,000 patients continue to have symptoms of moderate to severe RA with decreased quality of life as well as increased mortality. As a result, research is focusing on using new technologies that can improve our understanding of disease pathogenesis, stratify patients based on individualized pathology, and dissect nonobvious pathways that might contribute to disease.

ROLE OF GENETICS IN RA

Genetics clearly plays a role in the etiology and pathogenesis of RA (2). By far the most dominant influences are the class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) genes, most notably HLA-DR. A specific sequence known as the susceptibility epitope in the beta chain of HLA-DR is associated with increased risk and increased severity of RA. The HLA-DR genes are involved with antigen presentation of immunogenic peptides to cells in the adaptive immune system. The RA-associated MHC genes bind more avidly to peptides that have been modified through citrullination of arginine, which could account for the anti-citrullinated protein antibodies that are characteristic of this disease (3). The contribution of HLA-DR, although prominent, is still relatively modest. Individuals with copies of this gene have a 4- to 6-fold increase in risk. More than 100 other gene variants have been associated with increased risk of RA, although relative contributions are much lower than HLA-DR. Most of these genes are involved with immune response, cell trafficking, cell adhesion, and signal transduction. One of the most prominent examples is PTPN22, which is involved with signaling through the T cell receptor.

Although the search for genetic variance continues, we have likely reached the point of diminishing returns. For example, the disease concordance rate between identical twins is surprising low. If one twin develops RA the chance that the second twin will develop the disease is only 12% to 15% (4). That means we can sequence everyone’s genome and still miss more than 85% of the risk for RA. Some of the increased risk is due to environmental factors and other stochastic influences. Smoking is the best-defined risk and interacts with HLA-DR to amplify the risk of developing RA (possibly by inducing protein citrullination in the airway) (5). However, most of the environmental influences remain poorly defined or have a rather modest contribution.

We have referred to the gap between genetic associations and risk for RA as the “dark matter” for this disease. The term is borrowed from our astronomy colleagues who postulated that dark matter and dark energy in the interstices of the universe explain anomalies in the measurable dimensions. An analogy can be made to RA or many other complex human diseases. The “visible matter” in human disease is that what we have already measured, including cytokines, gene variance, histological variance, and the environment. But what is the remaining dark matter of RA? How do we account for this disease and what is its dark matter?

THE “DARK MATTER” OF RA: IMPRINTING CELLS WITH EPIGENETIC MARKS

A few years ago, we hypothesized that epigenetics is a crucial link between genetics and disease risk in RA (6). Epigenetics is defined as heritable changes in the genome that are independent of the DNA sequence. The sequence of DNA defines many aspects of our phenotype, such as our eye color and height, as well as disease risk in some cases. But gene regulation involves much more than transcription factors and requires a complex system of marks that can alter accessibility to the chromatin and affect binding characteristics of transcription factor motifs in regulatory regions. Through DNA methylation, histone marks, noncoding RNA, and other types of epigenetic mechanisms, genes are carefully regulated in a stereotypic fashion that can define the cell lineage, when cells should proliferate, and when they should be terminally differentiated. The epigenetic changes do not alter the sequence of nucleotides in DNA; instead, they decorate the DNA in a highly organized fashion to control how cells behave. When errors in epigenetic marks occur, catastrophic results can ensue with unregulated growth and malignant transformation. It is likely that these mechanisms contribute to many complex human diseases, most notably autoimmune diseases such as RA.

Our studies in epigenetics or RA initially focused on DNA methylation. This process, which is controlled by a series of enzymes called DNA methyltransferase, converts deoxycytidine to a methylated form when deoxycytidine and deoxyguanosine are adjacent to each other. These nucleotide pairs are sometimes referred to as CpG loci. Conventional wisdom suggests that methylation of CpG sites in the promoter regions silences the genes and prevents gene transcription. When a promoter region is demethylated, RNA transcription and gene expression can occur. In reality, this simplification and the situation is more complex in regulatory regions such as enhancers, introns, and gene bodies, where methylation can either increase or decrease transcription depending on the location and context.

Because every cell lineage has its own epigenetic pattern, studying mixed populations of cells creates significant hurdles to data analysis. We addressed this issue by focusing on a single cell type, namely, fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS). FLS, sometimes called synoviocytes, are mesenchymal cells that form the intimal lining of the synovium that boarders the synovial fluid space and are responsible for producing lubricants in the joint and allowing nutrients to diffuse from the blood to the cartilage (7). In RA synovium, the number of synoviocytes increases dramatically and they assume an aggressive phenotype that contributes to joint damage and persists even when cells are removed from the joint. When RA FLS are grown in culture, they display many properties of transformed cells compared with normal FLS. When implanted into cartilage in pre-clinical models, they autonomously invade into the matrix. The mechanism of aggressive behavior is not fully defined but could involve somatic mutations in genes such as the p53 tumor suppressor gene, abnormal SUMOylation, or dysregulation of genes such as PTEN and sentrin.

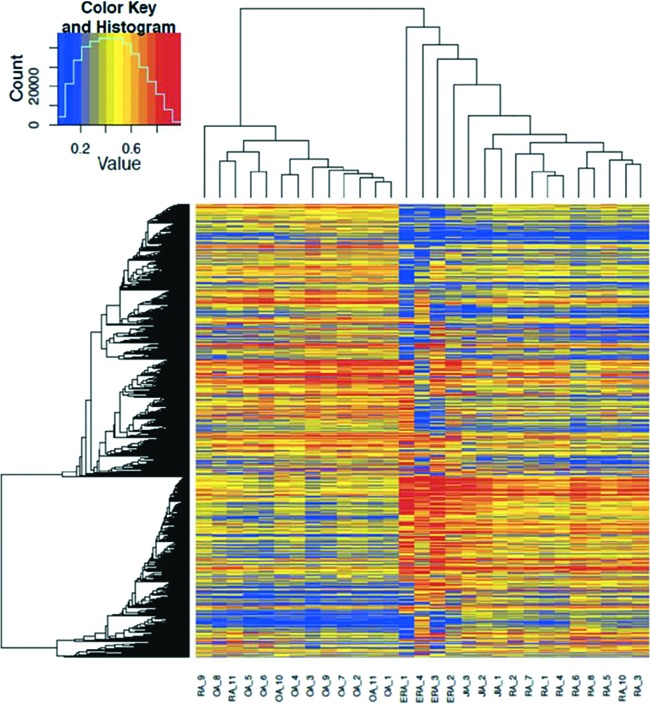

Our group used genome-wide methods to study FLS methylation patterns in RA instead of the more traditional candidate gene approach. RA FLS were then compared with control FLS, including cells from non-inflammatory arthritis such as osteoarthritis and from normal synovium. Much to our surprise, the pattern of DNA methylation of gene promoters in RA was distinctive and could be readily distinguished from non-RA FLS (Figure 1) (8). The methylation signature observed in RA was stable and persisted in culture for up to seven passages, suggesting that the cells are imprinted rather than transiently altered. Hierarchical clustering based solely on its epigenetic marks showed clear segregation of RA FLS, with differential methylation involving genes and pathways related to cell proliferation and differentiation, cell adhesion, and cell trafficking (9). This striking finding was independently replicated by another group independently and as well as our own confirmatory datasets (10). In addition, the promoter-focused studies were then expanded to other regulatory regions such as enhancers and revealed additional pathways involved with immune responses and cytokine signaling.

Fig. 1.

Hierarchical clustering of methylomes. Late rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and osteoarthritis (OA) segregate based on their methylation patterns. Early RA (ERA) and juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) forms separate subgroups within RA. Reprinted from Ai et al. (11).

Another important question related to the abnormal methylation signature in RA relates to the kinetics, i.e., when it occurs in the evolution of the disease. This is rather difficult to study because pre-RA joint samples are not readily available. However, synovial biopsy specimens in patients with very early RA have been obtained and the FLS derived from the samples evaluated (11). Although the sample size is small, the genome-wide methylation analysis showed that early RA synoviocytes are still distinguishable from osteoarthritis cells. Hierarchical clustering shows that they are similar to late RA synoviocytes with some interesting differences, although they form a separate subgroup within the RA methylation patterns (Figure 1). The key variations between early and late RA involve integrin, PDGF and Wnt/ß-catenin signaling pathways. Thus, the imprinting of synoviocytes in RA occurs early in disease but is not fixed. There is plasticity during disease progression and the methylation pattern evolves over time. The key areas that distinguish early and late RA are related to cell growth and differentiation which may explain the more aggressive nature of synoviocytes in late RA.

INTEGRATING LARGE DATASETS TO PRIORITIZE PATHOGENIC GENES

Methylation is only one aspect of gene regulation and does not always directly correlate with risk alleles or gene expression. To expand the analysis, we evaluated ways to integrate other large data sets with the methylation profile. In the simplest iteration of this approach, we integrated RA FLS transcriptome data, the methylome patterns and information on the genes with single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with increased RA risk. We used Venn diagrams to determine which genes appear in two or three different datasets (12). Pathway analysis of the “double” and “triple” evidence genes confirmed the importance of cell trafficking, cell adhesion, and immune responses as critical distinguishing features of RA FLS.

A limited subset of triple evidence genes was present in all three databases, which allowed us to prioritize them for subsequent studies. Some of them, such as class II MHC and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, were already known to participate in the pathogenesis of RA. Others had not been considered particularly important and only emerged because of the unbiased approach to target identification. Understanding the biology and role of these genes has been a valuable tool to dissect the pathogenesis of RA and discover unexpected genes that participate. For example, we showed that one of these genes, ELMO1, regulates synoviocyte migration and invasion and suggests that abnormal ELMO1 expression might contribute to joint damage. A second gene, PTPN11, encodes the proto-oncogene SHP-2. This gene is over-expressed in RA FLS, but its role in RA was poorly defined. By studying the PTPN11 methylome of RA FLS in greater detail, an abnormally methylated intron enhancer that includes a glucocorticoid responsive element was identified. The data provided a molecular mechanism for PTPN11 dysregulation in synovitis (13). Subsequent studies showed that targeting PTPN11 through genetic methods or with small molecules decreases arthritis severity a pre-clinical model. Thus, the unbiased analysis has helped identify two high priority targets for RA.

The gene that has attracted much of our attention is called the Limb Bud Heart Development gene or LBH. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in this gene and its regulatory regions have been associated with multiple autoimmune diseases including type 1 diabetes, celiac disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis. LBH is abnormally methylated in multiple locations in RA FLS, most notably in an upstream enhancer only approximately 85 bp away from the risk single nucleotide polymorphism. Detailed mechanistic studies showed that the risk allele and LBH deficiency alters the cell cycle and synoviocytes, leading to accumulation of DNA damage and S phase arrest (14). Genetic disruption of the gene in mice, which mimics the low LBH state observed in RA, increased arthritis severity in a pre-clinical model. These experiments identified a novel pathway for regulating cell growth and DNA integrity, and could lead to new ways to think about synovial proliferation and autoimmunity.

LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION

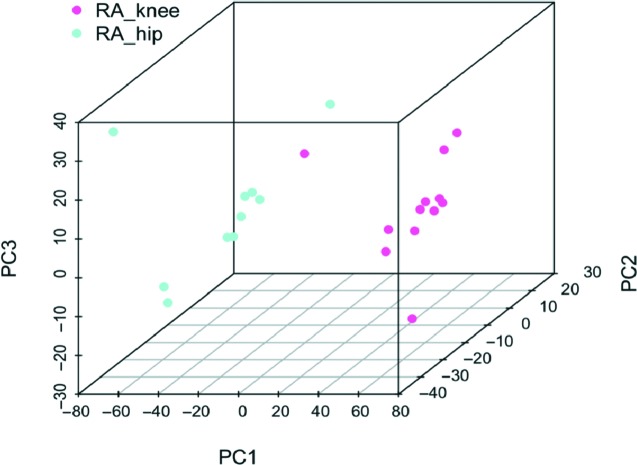

Careful examination of the methylation patterns in RA and osteoarthritis clearly showed that the two diseases could be distinguished. What was unexpected was the fact that individual joint locations also appeared to have some distinguishing epigenetic features (15). Because the biological samples in these studies are derived mainly from total joint replacements in late disease, the most common joints where tissues could be obtained were hips and knees. Within the RA group, principal component analysis surprisingly showed that hip and knee synoviocyte methylomes could be distinguished from each other (Figure 2). The joint-specific changes were also confirmed at the level of transcriptome by RNA-seq. The magnitude of the differences between RA hip and knee FLS was significant, but quantitatively less than the RA-osteoarthritis differences, as might be expected. Joint-specific DNA methylation patterns were also observed with osteoarthritis synoviocytes, with distinct DNA marks in osteoarthritis hip and knee cells.

Fig. 2.

Principle component analysis (PCA) of hip and knee methylomes in rheumatoid arthritis (RA). DNA methylation in fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) isolated from RA hips and knees showed distinct methylation patterns. The PCA shows differentially methylated loci that distinguish RA hip and knee FLS Reprinted from Ai et al. (15).

The fact that hip-knee differences were noted in both diseases led us to identify two different categories of joint-specific imprinting. The first type is “disease independent,” i.e., the differences between hips and knees occur regardless of whether the patient has RA or osteoarthritis (and is most likely true in normal individuals as well). The disease-independent genes, based on location, were recently confirmed by another group using an independent cohort and in pre-clinical models (16). The genes and pathways that distinguish hips and knees from each other in this category are enriched for HOX and WNT genes, which are critically involved in cell differentiation. The identification of these genes makes teleological sense because hips and knees have distinct biomechanical functions and they have different needs for their support structures. FLS in each location have been “instructed” on how to behave based upon the needs of that particular joint.

We then removed disease-independent pathways from the RA analysis and were surprised to find a panel of remaining genes that were only found in RA. We called these “disease-specific,” i.e., they only distinguish hips and knees from each other in RA but not osteoarthritis. These RA disease-specific pathways include signaling mechanisms for cytokines such as interleukin 6 (IL-6), IL-17, and IL-22. This is particularly relevant because some of these cytokines, most notably IL-6, can be targeted either with biologics or small molecule JAK inhibitors and are effective in RA.

The identification of distinct signaling pathways, based on joint location, has potential implications for how we treat patients and evaluate novel therapeutics. For example, highly targeted agents can be effective in some but not all RA patients. Clinicians also widely recognize that not all joints improve in a particular patient when he or she is treated with these agents. Joint-specific differences in signaling due to epigenetic imprinting provide a potential explanation for this phenomenon. In addition, clinical trials in RA do not evaluate which joint improves; joint counts are the primary indicators and we simply tabulate the total number of joints involved. It is possible that we are missing or underestimating therapeutic responses by not taking into account joint-specific biology and clinical status.

CONCLUSION

Understanding the epigenetics of autoimmunity and RA is only in its infancy. DNA methylation signatures are only the first step in this process, and those epigenetic marks do not operate in isolation. Our group has recently used genome-wide methods to evaluate histone marks and identify regions of open chromatin in RA synoviocytes to complement methylome data. Computational algorithms that look at the epigenetic landscape and define disease-specific chromatin states have been developed and we are now using this methodology to understand precisely how chromosomal structural elements distinguish RA from other diseases. The goal of these studies is not to identify targets that one could glean from reading the literature. Instead, the data will be used to find unexpected genes and pathways that can be leveraged. In addition, epigenomic modulators that alter histone marks and DNA methylation could be explored as ways to reverse abnormal imprinting of RA FLS. The unbiased methods provide a treasure trove of data to be mined and we are currently pursuing numerous potential targets that might be important in immune-mediated diseases.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: This work was funded in part by grants from the Rheum-atology Research Foundation, the Arthritis Foundation, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (R01 AR065466). Dr. Firestein has received grant funding from Gilead Sciences and Janssen Pharmaceuticals; and he has received consulting income from Roche and Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

DISCUSSION

Sacher, Cincinnati: Could you please discuss the disease course of sero-positive and sero-negative rheumatoid arthritis patients? Do sero-positive patients have more aggressive disease?

Firestein, San Diego: Yes. Clinically the sero-positive patients have much more aggressive disease and which means is they are almost always are the ones that have to undergo joint replacement. So our data are strongly biased towards sero-positive disease, and we don’t have enough information to show that they segregate out separately because most patients with sero-negative are a reasonably well controlled and have less joint damage.

Loeser, Chapel Hill: At the risk of insulting the ACCA members, you asked for normal synovium, and by looking around the room, I’m guessing there’s osteoarthritis synovium here!

Firestein, San Diego: Well, a previous questioner in the last talk said we were relics.

Loeser, Chapel Hill: I won’t go that far. But I’m wondering if you actually learned anything about osteoarthritis when you were comparing it to rheumatoid arthritis in terms of methylation patterns in osteoarthritis (OA) that might be useful for us that are in the OA world?

Firestein, San Diego: That’s an excellent question. It is very difficult to get normal synoviocytes. We have obtained about a half a dozen of those lines. We have looked at the methylation patterns and included that in a publication from a couple of years ago. The bottom line is that OA is not the same as normal but rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is much more different than both of those. One of the problems with analyzing normal synoviocytes is we don’t really know what normal is. They are generally anonymized samples from individuals who may have had OA, may have died from sepsis and their synoviocytes might have been exposed to medications or a variety of other things. But at least at this point we don’t think that there are huge differences between normal synoviocytes and those from osteoarthritis, particularly when comparing them to the differences with RA.

Schreiner, Los Altos: Gary, fascinating talk, but I was struck by a comment — a throwaway comment — that you saw stabilization of these methylation patterns when you remove these cells from an environment where we think they are acting in a complex of immune factors and other cell types, and that this methylation pattern was retained. I actually thought that was quite interesting. Have you done that on a clonal level to see whether or not these cells that you are passing in mice are influencing each other to maintain this methylation? Or once methylated is that it? And that the cell divisions maintain that infinitely, in terms of daughter cells.

Firestein, San Diego: So, it’s an important question — and we have looked at the effect of cytokines on DNA methyltransferases, and the methylation pattern and their expression can be modified. In fact, if you treat OA synoviocytes with cytokines for a long period of time, some of the characteristic patterns of RA appear. But when you wash the cytokines off in this artificial environment they revert to the OA methylation type. So, that leads me to believe that the methylation pattern not just due to exposure to cytokines. The most striking component of the observations is that these cells are actually imprinted. We published that the methylation pattern is stable for at least seven passages in culture which means many months. Ultimately, the cells senesce and it becomes quite difficult to assess. Epigenetic plasticity does create the potential for trying to unwind that pattern. We know that early RA is different from late RA, which is why I thought it was important to mention the plasticity aspect. I’m quite interested in trying to de-imprint — if that’s a word — some of these cells in order to have them revert to a more non-RA phenotype.

Schreiner, Los Altos: But what’s interesting is they don’t seem to do that spontaneously.

Firestein, San Diego: No, they do not. That’s because they’re imprinted.

Schreiner, Los Altos: Yes. Thank you.

Mackowiak, Baltimore: You probably explained this in great detail but I missed it. So, I need to ask the question: Epigenetics, in my innocence, implies that some event or factor has taken place, frequently during development. Perhaps malnutrition in the mom or some other hardship. What were these events that you identified that related to the RA epigenetic changes?

Firestein, San Diego: It’s not clear for rheumatoid arthritis, as you alluded. There are excellent data showing that diet can affect the methylation patterns, including methyl donors like folic acid and that hardship including cyclic feast and famine can not only change DNA methylation in the individuals that are affected but also in their progeny. For rheumatoid arthritis, the environmental influences are not nearly as well-defined. The best and most well-documented environmental influence on RAs is smoking. There are data showing that cigarette smoking can alter DNA methylation in particularly in the airway but also in peripheral blood. How that ultimately relates to the pathogeneses of disease is not clear. But we know that at least one environmental factor associated with RA has a clear effect on the methylation.

Wasserman, San Diego: We’re all friends, so I’m going to ask you this question: What about the children of RA patients? I mean, getting their synovium must be probably tricky, but do you think that they will be imprinted and therefore more likely to get rheumatoid arthritis?

Firestein, San Diego: It’s a difficult question to answer. Getting synovium is probably not a reasonable thing for IRB approval, which is one of the reasons why I alluded briefly to the notion of looking at peripheral blood. We’ve published on peripheral blood particularly naïve T-cells, CD4+ T cells where you can detect some of these same marks, and we’re now in the process of defining those marks in patients — high-risk patients and patients with RA. By studying blood it becomes a feasible experiment where we can look at the family members.

REFERENCES

- 1.Firestein GS. Kelley and Firestein’s Textbook of Rheumatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Elsevier; Etiology and pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. 2016 1115–66. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okada Y, Wu D, Trynka G, et al. Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis contributes to biology and drug discovery. Nature. 2014;506:376–81. doi: 10.1038/nature12873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill JA, Southwood S, Sette A, Jevnikar AM, Bell DA, et al. Cutting edge: the conversion of arginine to citrulline allows for a high-affinity peptide interaction with the rheumatoid arthritis-associated HLA-DRB1*0401 MHC class II molecule. J Immunol. 2003;171:538–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aho K, Koskenvuo M, Tuominen J, Kaprio J. Occurrence of rheumatoid arthritis in a nationwide series of twins. J Rheumatol. 1986;13:899–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sparks JA, Chang SC, Deane KD, et al. Associations of smoking and age with inflammatory joint signs among first-degree relatives without rheumatoid arthritis: results from the studies of the etiology of RA. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68((8)):1828–38. doi: 10.1002/art.39630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bottini N, Firestein GS. The duality of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis: passive responders and imprinted aggressors. Nature Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9:24–33. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartok B, Firestein GS. Fibroblast-like synoviocytes: key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Rev. 2010;233:233–55. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakano K, Whitaker JW, Boyle DL, Wang W, et al. DNA methylome signature of rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:110–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitaker J, Shoemaker R, Boyle DL, Hillman J, et al. An imprinted rheumatoid arthritis methylome signature reflects pathogenic phenotype. Genome Med. 2013;5:40. doi: 10.1186/gm444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de la Rica L, Urquiza JM, Gómez-Cabrero D, Islam AB, et al. Identification of novel markers in rheumatoid arthritis through integrated analysis of DNA methylation and microRNA expression. J Autoimmun. 2013;41:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ai R, Whitaker JW, Boyle DL, Tak PP, et al. DNA methylome signature in synoviocytes from patients with early rheumatoid arthritis compared to synoviocytes from patients with longstanding rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:1978–80. doi: 10.1002/art.39123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitaker JW, Boyle DL, Bartok B, Ball ST, et al. Integrative omics analysis of rheumatoid arthritis identifies non-obvious therapeutic targets. PLoS ONE. 2015;10((4)):e0124254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maeshima K, Stanford SM, Hammaker D, Sacchetti C, et al. Abnormal PTPN11 enhancer methylation promotes rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocyte aggressiveness and joint inflammation. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e86580. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.86580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuda S, Hammaker D, Topolewski K, Briegel KJ, et al. Regulation of the cell cycle and inflammatory arthritis by the transcription cofactor LBH Gene. J Immunol. 2017;199:2316–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ai R, Hammaker D, Boyle DL, Morgan R, et al. Joint-specific DNA methylation and transcriptome signatures in rheumatoid arthritis identify distinct pathogenic processes. Nature Commun. 2016;7:11849. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank-Bertoncelj M, Trenkmann M, Klein K, Karouzakis E, et al. Epigenetically-driven anatomical diversity of synovial fibroblasts guides joint-specific fibroblast functions. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14852. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]