Abstract

This review describes the outcomes for patients who underwent first rib resection for all three forms of thoracic outlet syndrome during a period of 10 years. The data were previously published in 2014 and the ACCA presentation, and this manuscript are derived largely from this work (1). Patients treated with first rib section from August 2003 through July 2013 were retrospectively reviewed using a prospectively maintained database. Five hundred thirty-eight patients underwent 594 first rib resections for indications of neurogenic (n = 308, 52%), venous (n = 261, 44%), and arterial (n = 25, 4%). Fifty-six (9.4%) patients had bilateral first rib resection surgery. Fifty-two (8.8%) patients had cervical ribs. Three hundred ninety-eight (67%) of the first rib resections were performed on female patients with a mean age of 33 years (range, 10 to 71 years). Three hundred forty (57%) were right-sided procedures. Seventy-five children (aged 18 years or younger) underwent first resection — 25 during the first 5 years, and 50 during the second 5 years. When comparing the second 5-year period with the first 5-year period, more patients had venous thoracic outlet syndrome (48% vs. 37%; P < 0.02). Fewer patients had neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome (48% vs. 58%; P < 0.05) and improved or fully resolved symptoms increased from 93% to 96%. Complications included 2 vein injuries, 2 hemothoraces, 4 hematomas, 138 pneumothoraces (23%), and 8 (1.3%) wound infections. Length of hospital stay was 1 day.

Excellent results were seen in this surgical series of neurogenic, venous, and arterial thoracic outlet syndrome due to appropriate selection of neurogenic patients, use of a standard protocol for venous patients, and expedient intervention in arterial patients. There is an increasing role for surgical intervention and children.

INTRODUCTION

Thoracic outlet syndrome is caused by compression of the neurovascular structures passing through the thoracic inlet. Patients with thoracic outlet syndrome can present with neurogenic, venous, and or arterial symptoms. These different kinds of thoracic outlet syndrome occur due to compression of the nerves of the brachial plexus, subclavian vein, or the subclavian artery by the scalene muscle, first rib, or fibrous bands (2–4).

Diagnosis and treatment of the various types of thoracic outlet syndrome can be a challenge as many patients do not respond to conservative management. Surgical intervention using first rib resection is offered to patients with neurogenic thoracic outlet who have failed to improve with physical therapy. Patients with symptomatic venous compression or thrombosis and those with the subclavian artery aneurysms, occlusion, or embolization are also offered first rib resection and may require vein or artery intervention. Postoperative physical therapy and follow-up for the first year after surgery has led to excellent results in our experience. The objective of this study was to evaluate the outcomes of patients who underwent first rib resection for thoracic outlet syndrome at one institution over a decade (1).

METHODS

A database of all patients treated with first rib resection with the thoracic outlet syndrome was maintained with institutional review board approval at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions in the Division of Vascular Surgery and Endovascular Therapy. Patients provided informed consent to be included in the database. Surgical intervention was offered to patients with neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome who were refractory to 8 weeks of physical therapy (5,6). Those patients with vascular thoracic outlet syndrome including venous thrombosis, venous compression, and arterial occlusion, embolization, and aneurysm formation, were also offered surgical intervention.

Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome is diagnosed by a detailed history and physical examination including the elevated arm stress test. Anterior scalene blocks using lidocaine or Botox (botulinum toxin type A) can be helpful in making the diagnosis. Duplex scans can easily make the diagnosis of subclavian vein thrombosis and arterial compression in abduction, thrombosis or aneurysm formation.

Data analysis was performed by diagnosis — neurogenic, venous, or arterial — and date of first rib resection using descriptive statistics, Student t tests, and chi-square tests. Stata software, version 13.1 (Stata Corp) was used and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

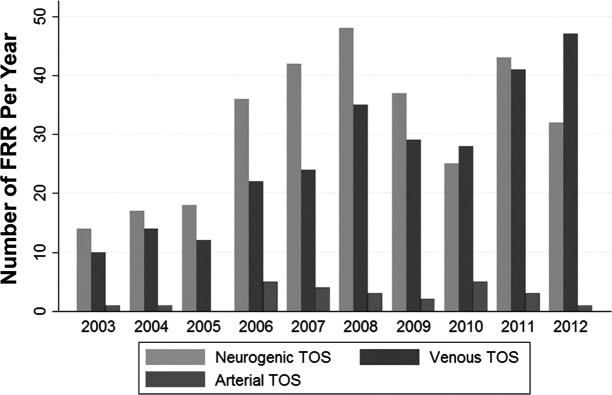

Five hundred thirty-eight patients underwent 594 first rib resections between August 2003 and July 2013 (Figure 1). Fifty-six patients (9.4%) had bilateral procedures. Three hundred eight patients (52%) had neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome; 261 patients (44%) had venous thoracic outlet syndrome; and 25 patients (4%) had arterial thoracic outlet syndrome. Three hundred ninety-eight patients’ (67%) first rib resections were performed on female patients. The mean age of all patients was 33 years old (range, 10 to 71 years). Patients with neurogenic thoracic outlet were older (35.9 years vs. 30.2 years; P < 0.05) and were more likely female (P < 0.001). There were 75 children (younger than 18 years): 25 in the first 5 years and 50 in the second 5 years. Three hundred forty patients (57%) underwent right-sided procedures; neurogenic patients had more left-sided procedures (P < 0.001), and venous patients had more right-sided procedures (P < 0.001). Fifty-two patients (8.8%) had cervical ribs. Those patients with arterial thoracic outlet were more likely to have a cervical rib (P < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Number of first rib resections (FRR) for neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS), venous TOS, and arterial TOS.

Complications included 138 (23%) pneumothoraces, 8 (1.3%) wound infections, 6 hematomas, 2 hemothoraces, and 2 vein injuries. The mean length of stay was 1 day. Excellent outcomes were maintained over the entire study period. Positive outcomes were seen in 93% in the first 5 years and 96% in the second 5-year period (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Patient Characteristics Between Those Treated During the First and Second Halves of the Study Period (August 2003 to July 2008 and August 2008 to July 2013)

| Patient Characteristics | 2003 to 2008 (n = 220) | 2008 to 2013 (n = 374) |

|---|---|---|

| Neurogenic TOS | 127 (58) | 181 (48) |

| Venous TOS | 82 (37) | 179 (48) |

| Arterial TOS | 11 (5) | 14 (3.7) |

| Female | 143 (65) | 255 (68) |

| White | 202 (92) | 337 (90) |

| Right-side surgery | 118 (54) | 222 (59) |

| Cervical ribs | 16 (7.3) | 36 (9.6) |

| Active smoker* | 34 (18) | 47 (13) |

| Age at surgery, y, mean (range) | 34.2 (10–62) | 32.7 (13–71) |

| Pneumothorax | 45 (20) | 93 (25) |

| Wound infection | 5 (2.3) | 3 (0.8) |

| Hematoma | 3 (1.4) | 3 (0.8) |

| Hemothorax | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Vein injury | 0 (0) | 2 (0.5) |

| Follow-up, mo, mean (range) | 20 (0–110) | 9.5 (0–41) |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise noted.

Smoking status was available for 188 of 220 patients treated during the first half of the study period and 357 of 374 patients treated during the second half.

TOS, thoracic outlet syndrome.

DISCUSSION

More than half of the patients in this review underwent first rib resection for neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. Those referred to us with neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome undergo initial physical therapy and two-thirds of these patients improve and will not require surgical intervention (7). Other patient factors including smoking, age, and chronic narcotic use more reliably predict long-term outcomes than the anterior scalene blocks (8).

Twice as many children were operated upon in our study in the second 5 years. We previously reported 35 adolescents who underwent first rib resection for neurogenic, venous (18), and arterial (8) indications. All of these young patients did well. Therefore, using the same indications for first rib resection as for adults, children can successfully undergo surgery (9).

The number of patients who had a successful outcome, as shown by resolution of pain and discomfort in the neurogenic patients, patent vein in the venous patients, and both patent artery and ischemic pain resolution in the arterial patients, increased from 93% in the first 5 years to 96% in the second 5 years. These excellent results are due to the development of a specialized surgical practice with established protocols and attention to outcomes by use of a registry.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: None disclosed.

DISCUSSION

Guze, Los Angeles: Julie, nicely done. How often or how long do you do physical therapy before you decide on doing surgery?

Freischlag, Winston-Salem: When I meet these patients, they usually have had their disease symptoms for at least 2 years, and so when I see them, frequently they have already had physical therapy. But it may be the wrong therapy, so we actually had published a physical therapy protocol in the literature so people can find it. We’ll put them in for 6 to 8 weeks to make sure their posture and their workplace is good and everything is appropriate, and about two-thirds will get better. Similarly, after you operate on neurogenic patients they have to go back at physical therapy, sometimes for 3 to 6 months, to get strong, to get better. Because as you remove the rib, the shoulder moves forward. So, 6 to 8 weeks unless they’ve been on an appropriate protocol when they’ve seen you.

Billings, Baton Rouge: This is a tangential comment, and this is the only time that this has been a forum for me to make this comment. I had a patient referred to me, and I’m from Louisiana, which is biblically fairly conservative. As she came to me from another oncologist, my first question to anybody who switches doctors is:

“Why did you switch doctors? I don’t want to fall down the same ditch.” She said, “Because I wanted to see a doctor who was more than just one rib,” meaning her former doctor was only a rib, which came from Adam. There’s been no other forum for me to mention this.

Freischlag, Winston-Salem: I’m trying to understand. Well, one thing I will follow up with is that is that these patients love to keep their ribs. So, the first rib is a very small thing, it’s not very big. When I was at UCLA, when I took over the division there, patients wanted to get their ribs back, and the guy that gave them back to them was named Adam. Which I found fascinating. However, at Hopkins, it took me 2 years to get approval so that they could have their ribs back. We worried about infection, we worried about lawsuits. So, finally in 2 years, we were able to autoclave them and give them back to patients. And actually it’s in this article in the Johns Hopkins Magazine. We had them bleach the ribs, put nail polish on them, and they wear them as necklaces, use them as wind chimes. If you didn’t know it was a bone you would love it. Some of the sports guys carry it in their pocket for good luck. However, at Davis — no problem giving patients back their rib, and similarly at Wake Forest. That’s a very interesting comment Dr. Billings, and maybe Adam can give us back all of our ribs.

Sacher, Cincinnati: My question is not as deep as that. Have you done any thrombophilic marker testing on the venous thoracic outlet syndrome patients? And second, have you seen a rare condition called Mondor’s disease which is a superficial thrombophlebitis of the anterior chest. Do you think that a hypercoagulable state or Monder’s disease may be related to venous thoracic outlet syndrome?

Freischlag, Winston-Salem: Do such patients have any sort of thrombotic tendency or some sort of abnormality in their hematologic profile? It’s a rare thing. We published on that as well. Usually these patients give you an incredible story of activity, and that’s why it’s called “effort thrombosis.” They have been playing tennis. They walk and run. They painted the ceiling of all their rooms in their house. And then they thrombose. And of the ones we tested, which was not all of them, we found that about 7% to 10% may have some sort of abnormality. It tends to be young women who were doing nothing. They were sitting reading a book, they were on a beach. There was no effort whatsoever, and then they thrombosed the vein. The most important information we find that out in these young women is that they actually have a higher incidence of miscarriage. You will find that they will have an abnormality on their hematologic profile. We treat the factor V Leiden patients very liberally, we’ll take the rib out initially. We do not keep them on long-term anticoagulation, but if they do have protein C or S deficiency, or another abnormality, then they will need to be put on long-term anticoagulants. I wouldn’t screen them all, but if they are young women who were doing nothing, we call this “couch potato thrombosis.” Those are the ones to test because they probably have an abnormality. As far as the other disease, Mondor’s disease, I haven’t seen that. There is a whole group of patients that will get thrombosis of the subclavian vein due to catheters or due to other manipulation such as for pacemakers. Those are a whole different group than we’re talking about here and those perhaps are the ones related to other diseases that we’ll see. These are healthy people by in large that tend to come to you with an event, they tend to be young. Occasionally though, if they don’t fit the profile of the history, then you need to go looking for more unusual activity. But 92% to 95% of them will be healthy people with a mechanical compression that you can fix with rib resection.

Sacher, Cincinnati: Why I ask about the Mondor’s disease, the patient I reference is a young woman, who, in fact, is an exercise therapist who spontaneously developed this anterior superficial thrombophlebitis. It’s intriguing about the association between exercise and thrombosis.

Freischlag, Winston-Salem: The patient’s deep veins were probably not affected — that would be more muscle-related. I haven’t seen that, but again you can interrogate the subclavian vein by duplex scan. It’s very easy. You don’t need to have a venogram or CT scans or MRIs. Your vascular lab can do that. Right underneath the clavicle they can take an image of that subclavian vein and you’ll know for sure whether it’s thrombosed. Also, if they are not swollen in their arms or hands, probably don’t have effort thrombosis disease.

REFERENCES

- 1.Orlando MS, Likes KC, Mirza S, Cao Y, Cohen A, et al. A decade of excellent outcomes after surgical intervention in 538 patients with throracic outlet syndrome. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:934–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson RW, Petrinec D. Surgical treatment of thoracic outlet compassion syndromes: diagnostic considerations and transaxillary first rib resection. Ann Vasc Surg. 1997;11:315–23. doi: 10.1007/s100169900053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fugate MW. Rotellini-Coltvet L, Freischlag JA. Current management of thoracic outlet syndrome. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2009;11:175–83. doi: 10.1007/s11936-009-0018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanders RJ, Hammond SL, Rao NM. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a review. Neurologist. 2008;14:365–73. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e318176b98d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang DC, Lidor AO, Matsen SL, Freischlag JA. Reported in-hospital complications following rib resections for neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg. 2007;21:564–70. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2007.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rochlin DH, Likes KC, Gilson MM, et al. Management of unresolved, recurrent, and/or contralateral neurogenic symptoms in patients following first rib resection. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:1061–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.03.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Likes K, Rochlin DH, Salditch Q, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of physician and self- referred patients for thoracic outlet syndrome is excellent. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28:1100–5. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rochlin DH, Gilson MM, Likes KC, et al. Quality-of-life scores in neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome patients undergoing first rib resection. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57:436–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.08.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang K, Graf E, Davis K, et al. Spectrum of thoracic outlet syndrome presentation in adolescents. Arch Surg. 2011;146:1383–7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]