ABSTRACT

Helicobacter pylori infection is common among Alaska native (AN) people, however scant gastric histopathologic data is available for this population. This study aimed to characterise gastric histopathology and H. pylori infection among AN people. We enrolled AN adults undergoing upper endoscopy. Gastric biopsy samples were evaluated for pathologic changes, the presence of H. pylori, and the presence of cag pathogenicity island-positive bacteria. Of 432 persons; two persons were diagnosed with gastric adenocarcinoma, two with MALT lymphoma, 40 (10%) with ulcers, and 51 (12%) with intestinal metaplasia. Fifty-five per cent of H. pylori-positive persons had cag pathogenicity island positive bacteria. The gastric antrum had the highest prevalence of acute and chronic moderate–severe gastritis. H. pylori-positive persons were 16 and four times more likely to have moderate–severe acute gastritis and chronic gastritis (p < 0.01), respectively. An intact cag pathogenicity island positive was correlated with moderate–severe acute antral gastritis (53% vs. 31%, p = 0.0003). H. pylori-positive persons were more likely to have moderate–severe acute and chronic gastritis compared to H. pylori-negative persons. Gastritis and intestinal metaplasia were most frequently found in the gastric antrum. Intact cag pathogenicity island positive was correlated with acute antral gastritis and intestinal metaplasia.

KEYWORDS: Helicobacter pylori, Alaska natives, gastritis, metaplasia, cagPAI

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) seroprevalence varies significantly between different populations in the USA as well as worldwide [1–3]. H. pylori is considered a group 1 carcinogen by the World Health Organization and populations with high H. pylori infection rates tend to have a higher risk for gastric cancer [4]. H. pylori infection typically progresses from gastritis and inflammation, to ulcers and eventually gastric cancer [5]. While H. pylori is found in over 50% of the world’s population [6], not all infected will go on to develop secondary pathologic changes.

Multiple factors have been identified that account for the virulence of particular H. pylori strains, of which, the cag pathogenicity island (cagPAI) is the best characterised. The cagPAI encodes a secretory system that allows one of its gene products, CagA, to be injected into cells and affect cell function [7]. Presence of the cagPAI has been found to be associated with more severe gastritis [7–10] and gastric cancer [11,12].

Previous studies have found that up to 75% of the Alaska Native (AN) population are infected with H. pylori, and that AN people are between 2 and 4 times more likely to develop stomach cancer than the white US population [13–16]. Even after successful treatment and eradication, reinfection is frequent, especially among AN persons living in rural villages where a 2-year re-infection rate of 22% has been documented [17]. These high rates of chronic infection likely contribute to disproportionately high rates of gastric cancer in AN people [14,18,19].

In order to understand the underlying upper gastrointestinal (GI) pathology in AN people who present with significant chronic upper abdominal complaints, we reviewed endoscopic and pathologic results of AN adults who underwent endoscopic evaluation. We identified individuals who were H. pylori positive by pathology and evaluated the relationship between H. pylori and gastric pathology.

Methods

Participant recruitment and evaluation was described previously [17]. Briefly, Alaska Native adults (≥ 18 years) scheduled for esophagogastroduodenoscopy for clinical indications from 1998 through 2005 were recruited from clinical sites around Alaska. We analysed data participants recruited from the Alaska Native Medical Center in Anchorage and from the regional hospitals in Bethel, Dillingham, and Nome. Patients were excluded from the study if they had a history of gastric cancer, gastric resection, were pregnant or had undergone cancer chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy within the previous year. Information regarding H. pylori treatment and recent antibiotic and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs) use was collected by chart review while information regarding tobacco and alcohol use was collected using a standard questionnaire.

Two gastric biopsies were collected for pathologic evaluation, one from the antrum and one from the fundus. These were processed and inoculated to solid media as described previously [17,20]. Gastric biopsy tissue obtained at the time of esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) were stained with Diff-Quik® (Mercedes Medical, USA) stain, for quantification of H. pylori and with haematoxylin and eosin stain for histological evaluation. Samples were considered positive for H. pylori if bacteria were observed on histologic examination. All biopsies were reviewed independently by two pathologists and graded using a tiered system. Pathologists were blinded to all other study results. Levels of acute gastritis were: None, Mild (rare clustered neutrophils), Moderate (neutrophils involved in several crypts), and Severe (multiple extensive crypt lesions in nearly every field). Levels of chronic gastritis were: None, Mild (lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates involving only the upper part of the mucosa), Moderate (lamina propria involved at all levels with expiation by lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates), and Severe (dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates at all levels with severe expansion or obliteration of epithelium). The levels of intestinal metaplasia (IM) were: None, Focal (rare or localised gland involvement), Patchy (several glands involved not in one focus), and Diffuse (most or all glands involved). The subjective concentration of H. pylori was graded using the following tiers: None, Focal (a few organisms found with difficulty), Moderate (multiple organisms in several areas), Numerous (organisms in nearly all areas). A sample was considered pathologic if at least one pathologist considered it to have pathologic changes.

During the EGD, gastric biopsy specimens were also collected for H. pylori culturing and genotyping, as previously described [21,22]. PCR analysis was performed on H. pylori DNA extracts to detect the presence of the right and left ends of the cagPAI, as well as the cagA, cagE, cagT, and virD4 genes (Supplemental Table 1). Due to potential sequence heterogeneity, two sets of primers were used for some genes. DNA extracts positive for all gene targets were considered to have originated from an H. pylori organism containing an intact cagPAI.

Anti-H. pylori IgG antibodies were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as described previously [23]. As a H. pylori standard serum is not available, optical density (OD) is used as a surrogate for antibody titer. OD measurements were divided into “high” and “low” based on a threshold of 1.5. This threshold was chosen as it was 3 times greater than the cut-point for anti-HP positivity and approximated the 80th percentile of the data distribution.

When combining results from the antral and fundal specimens and from the two pathologists, persons were considered to have H. pylori, gastritis or IM if it was found in ≥1 specimen or by ≥1 pathologist. The most severe grade was kept. Statistical analysis was performed by using StatXact 9 (Cytel Software Corp., USA) and SAS software v. 9 · 3 (SAS Institute Inc., USA). p-Values are two-sided and confidence limits and p values are exact when appropriate. Kappa statistic was used to determine inter-rater agreement. The following risk factor variables were analysed: age, sex, tobacco and alcohol use, study location, obesity (BMI ≥ 30), H. pylori concentration, elevated anti-HP antibodies, and presence of an intact cagPAI element. Univariate comparisons were made by use of the likelihood ratio chi-square test or the Cochran Armitage test of trend. Variables with a univariate p-value <0.25 were considered in the multi-variable models. All variables were entered into the model and a backwards elimination with re-entry was used to select the final statistical model. Variables were considered confounders and remained in the model if their exclusion changed the value of the coefficient(s) of interest by >15%. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Institutional Review Boards of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Alaska Area Indian Health Service approved the study. In addition, the study was approved by the following Alaska Native tribal health organisations: Southcentral Foundation, Norton Sound Health Corporation, Yukon Kuskokwim Health Corporation, Bristol Bay Area Health Corporation, the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium Board of Directors. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

A total of 432 Alaska Native individuals participated in this study. Sixty-three per cent of participants were female and the mean age was 49 years (Table 1). The most common reasons for endoscopy included stomach pain (84%), heartburn (71%), nausea (65%), or chronic symptoms including indigestion, reflux and epigastric pain (80%). Known risk factors for gastric pathology among participants included smoking (46%), any alcohol consumption (36%) and previous gastritis (47%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

General characteristics of H. pylori among Alaska native adults evaluated by esophagogastroduodenoscopy from 1998–2005.

| Demographics |

N (%) Total = 432 |

|---|---|

| % Female | 271 (63%) |

| Rural Site | 121 (28%) |

| Mean age | 49 years (range 18–88) |

| Smoke | 200 (46%) |

| Drink alcohol | 156 (36%) |

| Previous gastritis | 205 (47%) |

The most common endoscopic finding was gastritis (n = 358, 85%). Gastric ulcers were seen in 8% (n = 33) of patients and duodenal ulcers in 2% (n = 7). Ulcers were documented in the antrum [n = 9, 22%], duodenal bulb [n = 7, 17%], fundus [n = 10, 25%], the greater or lesser curvature of the stomach [n = 3, 8%], and at the pre pylorus or pylorus [n = 11, 18%]. Esophagitis was seen in 104 participants (24%).

Kappa statistics for agreement between pathologists for H. pylori, acute and chronic gastritis and IM are shown in Table 2. The two pathologists had good concordance on both presence/absence and grade of H. pylori and acute gastritis. The concordance was lower on chronic gastritis and the amount of IM.

Table 2.

Kappa statistics for pathology between raters in the H. pylori study of Alaska native adults; 1998–2005.

| Pathology outcome |

Kappa statistic (95% confidence interval) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of H. pylori | Amount Of H. pylori |

Presence and amount combined | |

| H. Pylori | 0.91 (0.87–0.95) | 0.72 (0.64–0.80) | 0.88 (0.85–0.91) |

| Acute gastritis | 0.78 (0.72–0.84) | 0.63 (0.53–0.74) | 0.75 (0.70–0.80) |

| Chronic gastritis | 0.65 (0.57–0.74) | 0.49 (0.41–0.57) | 0.64 (0.59–0.69) |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 0.88 (0.80–0.95) | 0.35 (0.14–0.56) | 0.76 (0.68–0.84) |

A total of 777 biopsies were obtained from 432 people of which 408 (53%) were from the antrum and 369 (47%) were from the fundus. 345 (80%) persons had two specimens (an antral and a fundal specimen), 24 (5%) had a fundal specimen only and 63 (15%) had an antral specimen only. Histological diagnoses are shown in Table 3. The overall prevalence of acute gastritis was 54% (n = 233) and chronic gastritis was 86% (n = 372). Fifty-one (12%) cases of IM were identified, two cases (0.5%) of gastric cancer and two cases (0.5%) of MALT lymphoma. Acute gastritis was more commonly detected in the antral (48%) than the fundal specimen (30%) and was more likely to be moderate–severe in the antral specimen (55%) than the fundal specimen (32%) (p < 0.01 for both). The pattern was similar for chronic gastritis with chronic gastritis observed more often in the antral (83%) than fundal specimens (74%) and more likely to be moderate–severe in the antrum (p < 0.01 for both). Similarly, IM was observed in 12% of antral specimens, but only 1% of fundal specimens (p < 0.0001).

Table 3.

Prevalence of histological diagnoses according to biopsy location; Alaska 1998–2005.

| Histological outcome | Antrum (n = 408) |

Fundus (n = 369) |

p-value (antrum vs. fundus) |

Antrum or fundus (n = 432) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute gastritis | 48% (n = 194) | 30% (n = 109) | < 0.0001 | 54% (n = 233) |

| Mild | 45% | 69% | 0.004 | 46% |

| Moderate | 48% | 28% | 46% | |

| Severe | 7% | 4% | 7% | |

| Chronic gastritis | 83% (n = 337) | 74% (n = 273) | 0.0001 | 86% (n = 372) |

| Mild | 31% | 66% | 33% | |

| Moderate | 55% | 29% | <0.0001 | 52% |

| Severe | 14% | 5% | 15% | |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 12% (n = 49) | 1% (n = 5) | <0.0001 | 12% (n = 51) |

| Focal | 39% | 40% | 0.22 | 39% |

| Patchy | 59% | 40% | 59% | |

| Diffuse | 2% | 20% | 4% | |

| Gastric carcinoma | 0.5% (n = 2) | 0% | Not tested | 0.5% (n = 2) |

| MALT lymphoma | 0.5% (n = 2) | 0.3% (n = 1) | Not tested | 0.5% (n = 2) |

| H. pylori present | 54% (n = 220) | 54% (n = 199) | 0.47 | 60% (n = 259) |

| Focal | 20% | 32% | <0.0001 | 17% |

| Moderate | 47% | 53% | 47% | |

| Numerous | 33% | 16% | 35% |

Of 259 persons who were H. pylori positive based on pathologic exam, the H. pylori infection was classified as focal in 45 (17%), moderate in 123 (48%), and numerous in 91 (35%) (Table 3). Two cases of gastric carcinoma and two cases of MALT lymphoma occurred; of these, one gastric carcinoma case and both of the MALT lymphoma cases were positive for H. pylori. Presence of H. pylori was similar between antrum and fundus with 54% of samples positive for H. pylori in both locations, however, H. pylori was more likely graded as numerous in the antral (n = 135, 33%) than the fundal specimen (n = 32, 16%, p < 0.01). Among those people positive for H. pylori, 78% and 98% had acute and chronic gastritis respectively, compared to 18% and 69% of persons without H. pylori (when the mild, moderate and severe categories are combined, p < 0.0001, Table 4). When the prevalence of moderate–severe gastritis was compared between the H. pylori positive and negative participants, it was found that H. pylori-positive participants had 16 times the prevalence of moderate–severe acute gastritis (p < 0.01) and 3.9 times the prevalence of moderate–severe chronic gastritis (p < 0.01) when compared to H. pylori-negative participants (Table 4). This elevated prevalence was found irrespective of the gastric location of the observed gastritis.

Table 4.

Pathology of Alaska native adults positive and negative for H. pylori; 1998–2005.

| Characteristic |

H. Pylori status |

Prevalence ratio (95%CI) a |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n = 259) |

Negative (n = 173) |

|||

| % Female | 59% (153) | 68% (118) | 0.87 (0.4, 1.0) | |

| Age ≥50 Years | 41% (106) | 49% (85) | 0.83 (0.7, 1.0) | |

| Acute gastritis (fundal and antral combined) | None | 22% (57) | 82% (142) | ref |

| Mild | 32% (82) | 15% (26) | ||

| Moderate | 40% (104) | 2% (4) | 16.0 (6.7, 38.4) b | |

| Severe | 6% (16) | 1% (1) | ||

| Fundus | None | 56% (124) | 91% (136) | ref |

| Mild | 29% (63) | 8% (12) | ||

| Moderate | 13% (29) | 1% (1) | 22.3 (3.1, 161.6) b | |

| Severe | 2% (4) | 0% (0) | ||

| Antrum | None | 30% (73) | 88% (141) | ref |

| Mild | 29% (71) | 10% (16) | ||

| Moderate | 37% (91) | 2% (3) | 16.8 (6.3, 44.7) b | |

| Severe | 5% (12) | 1% (1) | ||

| Chronic gastritis (fundal and antral combined) | None | 2% (6) | 31% (54) | ref |

| Mild | 15% (39) | 47% (82) | ||

| Moderate | 63% (162) | 19% (33) | 3.9 (2.9, 5.2) b | |

| Severe | 20% (52) | 2% (4) | ||

| Fundus | None | 8% (18) | 52% (78) | ref |

| Mild | 53% (117) | 42% (63) | ||

| Moderate | 34% (75) | 3% (5) | 7.2 (3.6, 14.4) b | |

| Severe | 5% (10) | 2% (3) | ||

| Antrum | None | 2% (6) | 40% (65) | ref |

| Mild | 16% (40) | 41% (66) | ||

| Moderate | 63% (155) | 18% (29) | 4.4 (3.1, 6.1) b | |

| Severe | 19% (46) | 1% (1) | ||

| Intestinal metaplasia | 13% (34) | 10% (17) | 1.3 (0.8, 2.3) | |

| Ulcer | 9% (24) | 9% (16) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | |

| Duodenal ulcer | 2% (6) | 1% (1) | 4.0 (0.5, 33.0) | |

| Gastric ulcer | 7% (18) | 9% (15) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.5) | |

aPrevalence ratio represents the prevalence of the outcome in question in persons positive for H. pylori compared to those negative for H. pylori.

bPrevalence ratio for gastritis outcomes compares those with moderate or severe gastritis combined versus those with none or mild gastritis.

Among persons who were H. pylori positive, factors associated with acute and chronic gastritis and IM are shown in Table 5. An increasing concentration of H. pylori organisms identified in the biopsy specimen was positively correlated with the proportion of people who had moderate–severe acute and chronic gastritis; 60% and 90% of people who had numerous H. pylori on exam had moderate–severe acute and chronic gastritis, respectively. Similarly, moderate serve chronic gastritis was more common among persons with high levels of IgG antibody (79% vs. 93%, p < 0.0001) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Factors associated with chronic (moderate/severe) and acute (moderate/severe) gastritis and intestinal metaplasia among Alaska native adults positive for H. pylori (Hp) by histological assessment; 1998–2005.

| Factor | Level (n) | Acute gastritis (mod/sev) |

Chronic gastritis (mod/sev) |

Intestinal metaplasia |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % with (n) | p-value | % with (n) | p-value | % with (n) | p-value | ||

| Age ≥50 Years | Yes (n = 106) | 43% (46) | 0.43 | 76% (81) | 0.03 d | 22% (23) | 0.0007 d |

| No (n = 153) | 48% (74) | 87% (133) | 7% (11) | ||||

| Sex | F (n = 153) | 44% (67) | 0.32 | 84% (129) | 0.39 | 10% (16) | 0.13 |

| M (n = 106) | 50% (53) | 80% (85) | 17% (18) | ||||

| Study arm | Urban (n = 177) | 47% (84) | 0.59 | 81% (143) | 0.24 | 14% (24) | 0.76 |

| Rural (n = 82) | 44% (36) | 87% (71) | 12% (10) | ||||

| Obese (BMI ≥30 | Yes (n = 82) | 49% (40) | 0.57 | 85% (70) | 0.47 | 11% (9) | 0.47 |

| No (n = 147) | 45% (66) | 82% (120) | 14% (21) | ||||

| Alcohol use (any) | Yes (n = 98) | 50% (49) | 0.38 | 86% (84) | 0.35 | 13% (13) | 0.86 |

| No (n = 160) | 44% (71) | 81% (130) | 13% (20) | ||||

| Current smoker a | Yes (n = 62) | 39% (24) | 0.17 | 74% (46) | 0.05 d | 15% (9) | 0.71 |

| No (n = 197) | 49% (96) | 85% (168) | 13% (25) | ||||

| Concentration of HP | Focal (n = 45) | 18% (8) | < 0.0001 d | 53% (24) | <0.0001 d | 16% (7) | 0.85 |

| Moderate (n = 123) | 46% (57) | 88% (108) | 12% (15) | ||||

| Numerous (n = 91) | 60% (55) | 90% (82) | 13% (12) | ||||

| High anti-HP IgG c | Yes (n = 45) | 58% (26) | 0.07 | 93% (42) | 0.01 | 4% (2) | 0.03 |

| No (n = 185) | 43% (79) | 79% (146) | 15% (28) | ||||

| Intact CAGe | Yes (n = 120) | 62% (74) | 0.0002 d | 88% (105) | 0.79 | 16% (19) | 0.09 d |

| No (n = 97) | 36% (35) | 89% (86) | 8% (8) | ||||

a ≥10 cigarettes/day.

b ≥20 delta over baseline.

c OD ≥ 1.5.

d Significant in multivariate model.

ecagPAI.

Thirty-one people had evidence of acute gastritis but did not have any H. pylori detected by histology. Among H. pylori-negative individuals, persons with acute gastritis were more likely to be using proton pump inhibitors (p = 0.04) and less likely to be using H2 blockers (p = 0.02) than individuals who did not have signs of gastritis. Within this group, no association was found for reported alcohol, NSAID, antibiotic use or with previous H. pylori treatment (data not shown). No significant differences in exposures were found among the 119 H. pylori-negative individuals with chronic gastritis when compared to those without gastritis.

No differences were detected between persons with and without ulcers in terms of presence of H. pylori by histology (Table 4), amount of H. pylori antibody at study entry (p = 0.72), presence and amount of acute gastritis (p = 0.56) or presence and amount of chronic gastritis (p = 0.43) (data not shown).

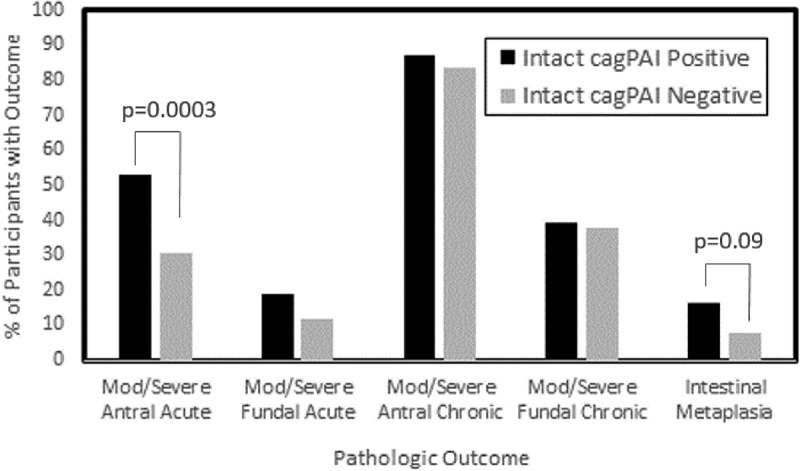

Of the 432 persons enrolled in the study, 217 were positive for H. pylori by culture. Of these, 129 (55%) of the Hp carried an intact cagPAI element (data not shown). Individuals with an intact cagPAI were more likely to have moderate to severe acute gastritis (p = 0.0002) when compared to persons without an intact cagPAI (Table 5). When evaluated by gastric location, the trend remained for moderate–severe acute antral gastritis (p = 0.0003) but not fundal gastritis (p = 0.16) (Figure 1). No relationship was seen between cagPAI integrity and chronic gastritis (Table 4).

Figure 1.

On univariate and multivariable analysis, among persons positive for H. pylori, age greater than 50 years was associated with an decreased risk of moderate–severe chronic gastritis (p = 0.01) and increased risk of IM (p = 0.003). Presence of an intact cagPAI was associated with increased risk of IM (p = 0.047) and acute gastritis (p = 0.001). Increased H. pylori concentration on pathology was associated with increased acute gastritis (p = 0.047) and chronic gastritis (p < 0.0001), while current smoking was associated with a decreased risk of chronic gastritis (p = 0.05) (Table 5). No association was found between H. pylori concentration and gender, obesity or alcohol use.

Discussion

Alaska Native persons have previously been shown to have a very high rate of H. pylori infection, ulcers, and gastric cancer [14–16]. This study characterised the distribution of H. pylori infection and characterised the pathologic changes found in Alaska Native patients who underwent upper endoscopy for gastric complaints. The high prevalence of inflammation found in this study is concerning as these types of lesions have a high risk of progressing to cancer.

Overall, 85% of participants had gastritis, 12% had IM, and 10% had ulcers. Both gastritis and IM were more common in the antrum than the fundus, while ulcers were seen five times more frequently in the body of the stomach compared to the duodenum. A high proportion of participants tested positive for H. pylori by histology, however this number cannot be considered reflective of the general population due to recruitment bias. H. pylori-positive participants were significantly more likely to have acute gastritis and chronic gastritis. In comparison to the gastric fundus, the antrum was more likely to have evidence of both acute and chronic gastritis and antral disease was more frequently categorised as severe. The antrum was more likely to have H. pylori present and the antrum was more likely to be infected with H. pylori with an intact cagPAI element. These observations are likely interrelated since specimens with more numerous H. pylori (higher concentration) were more likely to exhibit moderate to severe acute and chronic gastritis as well as IM.

Few studies have directly compared pathologist consistency in diagnosis of gastritis or H. pylori infection [24–26]. Here, specimens were reviewed by two pathologists independently, both as a way to validate the findings, but also to understand inter-pathologist variation. A high concordance was found between the two pathologists on the presence, absence, and concentration of H. pylori, the presence of IM, as well as the grade of acute gastritis, and a lower concordance was found between pathologists regarding chronic gastritis and grade of IM. This highlights the importance of including multiple evaluators in pathology studies.

Although H. pylori was found with equal frequency in the fundus and antrum, antral specimens were found to have a higher concentration of bacteria. In addition, antral specimens were more likely to have IM and the more severe forms of both acute and chronic gastritis. These results agree with previous work that have shown while the presence of H. pylori is equal in the body and fundus of affected individuals, the concentration of bacteria and the presence of disease is significantly greater in the antrum [27–30]. We found a direct correlation between the concentration of H. pylori in a specimen and the severity of both active and chronic gastritis. This finding was reinforced by the finding that the OD of H. pylori antibodies (a surrogate for concentration) correlated with both H. pylori concentration and gastritis severity. This finding supports earlier studies showing that the density of antibodies to H. pylori in blood correlates with the severity of antral gastritis and concentration of H. pylori found in the stomach [31,32].

A few individuals had evidence of gastritis without any histologic evidence of H. pylori infection. These persons were more likely to use proton pump inhibitors and less likely to use a H2-receptor blocker when compared to persons who did not have gastritis. It is uncertain if these medications are affecting the H. pylori infection or reflect symptom severity and management. No association was seen between gastritis in those without H. pylori infection and NSAID use or alcohol consumption, known causes of gastritis. This is consistent with findings from an earlier case-series among Alaska Native persons in Anchorage which found evidence of gastritis in individuals in the absence of H. pylori infection or other known causes of gastritis [33]. Whether these findings represent persistent mucosal changes after H. pylori infection or undetected infection is not known.

Previous work has suggested that the age of acquisition of H. pylori increases the likelihood that a person will develop cancer later in life [34–36]. It is thought that infection at an early age allows time for pathological progression through multiple stages, that ultimately result in gastric cancer [35]. Gastric H. pylori infection initially causes inflammation which leads to destruction of parietal cells and results in a drop in stomach acidity. This change in acidity promotes further gastric infection and inflammation, while creating an unfavourable environment for H. pylori in the duodenum. Thus, populations in the early stages of infection are thought to have a low ratio of gastric to duodenal ulcers, while those in later stages have a high ratio. This information makes it possible to identify populations who are infected early in life, and at increased risk of cancer, as they have a higher ratio of gastric to duodenal ulcers. This study found a 4:1 ratio of gastric to duodenal ulcers. This ratio is similar to what was observed in earlier studies involving Alaska Natives and other Indigenous Arctic populations [33,37,38], but the reverse of what is reported from the rest of the USA and many other populations around the world [39–42]. The high ratio of gastric ulcers is consistent with the idea that individuals in this population tend to acquired H. pylori infection at an early age and are at an increased risk of cancer [16,43].

A significant association was found between infection with H. pylori with an intact cagPAI and both IM and moderate–severe acute antral gastritis. While the low number of cancers identified in this study makes it impossible to evaluate an association between genotype and cancer, it was possible to evaluate the association with intermediates in the cascade towards cancer. The progression from normal tissue to cancerous tissue is thought to be a change from acute gastritis to chronic gastritis to IM to cancer [44,45]. The association seen here, between cagPAI and both IM and moderate–severe acute antral gastritis, agrees with previous reports that have shown an intact element is related to more severe disease [7,11,12,21,46–48]. A previous study in Alaska Native people found that over 90% of both individuals with gastric cancer and healthy individuals had antibodies against the CagA protein[19], indicating that exposure to bacteria expressing and exporting this protein is very common. Here we show that while exposure to CagA expressing bacterial strains may be common, active infection with a strain carrying an intact element is less common and is associated with disease.

The multivariable analysis identified known risk factors for more severe disease, including older age, presence of an intact cagPAI and bacterial concentration in gastric biopsy specimens. One unexpected finding was an inverse association between current smoking and risk of moderate–severe chronic gastritis. Smoking is known to be associated with gastric cancer [49,50]. The inverse relationship found here is likely due to a flaw in the questionnaire, which only asked about current smoking, not smoking history. This led to an underestimation of smoking exposure in the study population.

It is important to recognise that this study recruited symptomatic individuals, and therefore does not reflect the general population. The limited number of carcinoma and MALT cases made it impossible for any analysis of these outcomes. Ulcers were not found to be associated with H. pylori infection or gastritis, however very few ulcers were diagnosed as part of this study, thus limiting the ability to evaluate this outcome.

This study highlights the association between gastric lesion severity, the concentration of H. pylori, and the presence of cagPAI in Alaska Native people. It has previously been shown that Alaska Native people are at an increased risk for gastric cancer compared to the rest of the USA population [13–16]. While early screening for Alaska Native people for colorectal cancer secondary to the increased risk of this type of cancer in the Alaska Native population is recommended by the Alaska Native Medical Center [51] no specific recommendations have been created for this population regarding gastric cancer. Given the gastric pathology observed in this study and the increased risk of gastric cancer among Alaska Native persons, it would be appropriate to consider whether a population-based screening approach for gastric cancer should be considered. Further studies are needed to evaluate screening and treatment methods for H. pylori and gastric cancer in this population.

Funding Statement

This project was funded in part by the Indian Health Service [U26IHS300410]. This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a Native American Research Centers for Health (NARCH) grant no.: 1 U26 94 00005.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Julie Morris and Alisa Reasonover for their work culturing the H. pylori organisms.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].Smith JG, Li W, Rosson RS.. Prevalence, clinical and endoscopic predictors of Helicobacter pylori infection in an urban population. Conn Med. 2009March;73(3):133–9. PubMed PMID: 19353987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Go MF. Review article: natural history and epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002March;16(Suppl 1):3–15. PubMed PMID: 11849122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Everhart JE, Kruszon-Moran D, Perez-Perez GI, et al. Seroprevalence and ethnic differences in Helicobacter pylori infection among adults in the USA. J Infect Dis. 2000April;181(4):1359–1363. PubMed PMID: 10762567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991October17;325(16):1127–1131. PubMed PMID: 1891020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kuipers EJ, Uyterlinde AM, Pena AS, et al. Long-term sequelae of Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Lancet. 1995June17;345(8964):1525–1528. PubMed PMID: 7791437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bruce MG, Maaroos HI, Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2008; October 13 Suppl 1:1–6. PubMed PMID: 18783514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jones KR, Whitmire JM, Merrell DS. A tale of two toxins: helicobacter Pylori CagA and VacA modulate host pathways that impact disease. Front Microbiol. 2010;1:115 PubMed PMID: 21687723; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3109773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tohidpour A. CagA-mediated pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori. Microb Pathog. 2016April;93:44–55. PubMed PMID: 26796299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Occhialini A, Marais A, Urdaci M, et al. Composition and gene expression of the cag pathogenicity island in Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from gastric carcinoma and gastritis patients in Costa Rica. Infect Immun. 2001March;69(3):1902–1908. PubMed PMID: 11179371; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC98100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jenks PJ, Megraud F, Labigne A. Clinical outcome after infection with Helicobacter pylori does not appear to be reliably predicted by the presence of any of the genes of the cag pathogenicity island. Gut. 1998December;43(6):752–758. PubMed PMID: 9824600; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1727354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Blaser MJ, Perez-Perez GI, Kleanthous H, et al. Infection with Helicobacter pylori strains possessing cagA is associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res. 1995May15;55(10):2111–2115. PubMed PMID: 7743510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gwack J, Shin A, Kim CS, et al. CagA-producing Helicobacter pylori and increased risk of gastric cancer: a nested case-control study in Korea. Br J Cancer. 2006September04;95(5):639–641. PubMed PMID: 16909137; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2360680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kelly JJ, Lanier AP, Schade T, et al. Cancer disparities among Alaska native people, 1970-2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014December18;11:E221 PubMed PMID: 25523352; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4273544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wiggins CL, Perdue DG, Henderson JA, et al. Gastric cancer among American Indians and Alaska natives in the USA, 1999-2004. Cancer. 2008September01;113(5 Suppl):1225–1233. PubMed PMID: 18720378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tveit AH, Bruce MG, Bruden DL, et al. Alaska sentinel surveillance study of Helicobacter pylori isolates from Alaska native persons from 2000 to 2008. J Clin Microbiol. 2011October;49(10):3638–3643. PubMed PMID: 21813726; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3187320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Parkinson AJ, Gold BD, Bulkow L, et al. High prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in the Alaska native population and association with low serum ferritin levels in young adults. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000November;7(6):885–888. PubMed PMID: 11063492; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC95979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bruce MG, Bruden DL, Morris JM, et al. Reinfection after successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori in three different populations in Alaska. Epidemiol Infect. 2015April;143(6):1236–1246. PubMed PMID: 25068917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].McMahon BJ, Bruce MG, Koch A, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in Arctic regions with a high prevalence of infection: expert commentary. Epidemiol Infect. 2016January;144(2):225–233. PubMed PMID: 26094936; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4697284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Keck JW, Miernyk KM, Bulkow LR, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and markers of gastric cancer risk in Alaska Native persons: a retrospective case-control study. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014June;28(6):305–310. PubMed PMID: 24945184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4072235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].McMahon BJ, Bruce MG, Hennessy TW, et al. Reinfection after successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori: a 2-year prospective study in Alaska Natives. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006April15;23(8):1215–1223. PubMed PMID: 16611283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Miernyk K, Morris J, Bruden D, et al. Characterization of Helicobacter pylori cagA and vacA genotypes among Alaskans and their correlation with clinical disease. J Clin Microbiol. 2011September;49(9):3114–3121. PubMed PMID: 21752979; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3165571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].McMahon BJ, Hennessy TW, Bensler JM, et al. The relationship among previous antimicrobial use, antimicrobial resistance, and treatment outcomes for Helicobacter pylori infections. Ann Intern Med. 2003September16;139(6):463–469. PubMed PMID: 13679322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Miernyk KM, Bruden DL, Bruce MG, et al. Dynamics of Helicobacter pylori-specific immunoglobulin G for 2 years after successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection in an American Indian and Alaska native population. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007January;14(1):85–86. PubMed PMID: 17079433; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1797704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Andrew A, Wyatt JI, Dixon MF. Observer variation in the assessment of chronic gastritis according to the Sydney system. Histopathology. 1994October;25(4):317–322. PubMed PMID: 7835836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ramirez-Mendoza P, Angeles-Angeles A, Aguirre-Garcia J, et al. [Concordance between pathologists in the diagnosis of gastric atrophy according with the OLGA system]. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2009Apr-Jun;74(2):88–93. PubMed PMID: 19666288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Isajevs S, Liepniece-Karele I, Janciauskas D, et al. Gastritis staging: interobserver agreement by applying OLGA and OLGIM systems. Virchows Arch. 2014April;464(4):403–407. PubMed PMID: 24477629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bayerdorffer E, Lehn N, Hatz R, et al. Difference in expression of Helicobacter pylori gastritis in antrum and body. Gastroenterology. 1992May;102(5):1575–1582. PubMed PMID: 1568567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Stolte M, Eidt S, Ohnsmann A. Differences in Helicobacter pylori associated gastritis in the antrum and body of the stomach. Z Gastroenterol. 1990May;28(5):229–233. PubMed PMID: 2402931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kuipers EJ, Uyterlinde AM, Pena AS, et al. Increase of Helicobacter pylori-associated corpus gastritis during acid suppressive therapy: implications for long-term safety. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995September;90(9):1401–1406. PubMed PMID: 7661157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Siurala M, Sipponen P, Kekki M. Campylobacter pylori in a sample of Finnish population: relations to morphology and functions of the gastric mucosa. Gut. 1988July;29(7):909–915. PubMed PMID: 3396964; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1433761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kreuning J, Lindeman J, Biemond I, et al. Relation between IgG and IgA antibody titres against Helicobacter pylori in serum and severity of gastritis in asymptomatic subjects. J Clin Pathol. 1994March;47(3):227–231. PubMed PMID: 8163693; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC501900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Plebani M, Basso D, Cassaro M, et al. Helicobacter pylori serology in patients with chronic gastritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996May;91(5):954–958. PubMed PMID: 8633587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Sacco F, Bruce MG, McMahon BJ, et al. A prospective evaluation of 200 upper endoscopies performed in Alaska native persons. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2007April;66(2):144–152. PubMed PMID: 17515254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Blaser MJ, Chyou PH, Nomura A. Age at establishment of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma, gastric ulcer, and duodenal ulcer risk. Cancer Res. 1995February1;55(3):562–565. PubMed PMID: 7834625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process–first American cancer society award lecture on cancer epidemiology and prevention. Cancer Res. 1992December15;52(24):6735–6740. PubMed PMID: 1458460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Howson CP, Hiyama T, Wynder EL. The decline in gastric cancer: epidemiology of an unplanned triumph. Epidemiol Rev. 1986;8: 1–27. PubMed PMID: 3533579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cheung J, Goodman KJ, Girgis S, et al. Disease manifestations of Helicobacter pylori infection in Arctic Canada: using epidemiology to address community concerns. BMJ Open. 2014;4(1):e003689 PubMed PMID: 24401722; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3902307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Fenger HJ, Gudmand-Hoyer E. Peptic ulcer in Greenland Inuit: evidence for a low prevalence of duodenal ulcer. Int J Circumpolar Health. 1997July;56(3):64–69. PubMed PMID: 9332130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Thompson WM, Ackerstein H. Peptic ulcer disease in the Alaska natives: a four-year (1967-1971) retrospective study. Alaska Med. 2005Apr-Jun;47(1): 22 PubMed PMID: 16295985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Feinstein LB, Holman RC, Yorita Christensen KL, et al. Trends in hospitalizations for peptic ulcer disease, USA, 1998-2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010September;16(9):1410–1418. PubMed PMID: 20735925; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3294961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Perez-Aisa MA, Del Pino D, Siles M, et al. Clinical trends in ulcer diagnosis in a population with high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005January1;21(1):65–72. PubMed PMID: 15644047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Serin A, Tankurt E, Sarkis C, et al. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with gastric and duodenal ulcers - a 10-year, single-centre experience. Prz Gastroenterol. 2015;10(3):160–163. PubMed PMID: 26516382; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4607692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Carmack AM, Schade TL, Sallison I, et al. Cancer in the Alaska native People: 1969-2013 the 45-year report. Alaska Native Tumor Registry, Alaska Native Epidemiology Center, Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium 2015. 2015.

- [44].Correa P, Haenszel W, Cuello C, et al. A model for gastric cancer epidemiology. Lancet. 1975July12;2(7924):58–60. PubMed PMID: 49653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Correa P, Haenszel W, Cuello C, et al. Gastric precancerous process in a high risk population: cohort follow-up. Cancer Res. 1990August01;50(15):4737–4740. PubMed PMID: 2369748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Basso D, Zambon CF, Letley DP, et al. Clinical relevance of Helicobacter pylori cagA and vacA gene polymorphisms. Gastroenterology. 2008July;135(1):91–99. PubMed PMID: 18474244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Memon AA, Hussein NR, Miendje Deyi VY, et al. Vacuolating cytotoxin genotypes are strong markers of gastric cancer and duodenal ulcer-associated Helicobacter pylori strains: a matched case-control study. J Clin Microbiol. 2014August;52(8):2984–2989. PubMed PMID: 24920772; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4136171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Nomura AM, Perez-Perez GI, Lee J, et al. Relation between Helicobacter pylori cagA status and risk of peptic ulcer disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2002June1;155(11):1054–1059. PubMed PMID: 12034584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Bornschein J, Malfertheiner P. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. Dig Dis. 2014;323:249–264. PubMed PMID: 24732191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Gonzalez CA, Lopez-Carrillo L. Helicobacter pylori, nutrition and smoking interactions: their impact in gastric carcinogenesis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;451:6–14. PubMed PMID: 20030576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Alaska Native Medical Center Colorectal Cancer Screening Guidelines. http://anthctodayorg/epicenter/assets/colon/ANMC-CR-ScreeningGuideline2013v082014pdf. 2013