Highlights

-

•

Epidemiological Trial of Hypertension in North Africa (ETHNA-Tunisia) was a multicentre, epidemiological, cross-sectional study conducted in Tunisia to evaluate the prevalence and clinical profile of hypertension.

-

•

The total prevalence of hypertension was 47.4% (adjusted for age: 26.9%) and only 37.1% were controlled.

-

•

Greater awareness and improved management of hypertension are needed in Tunisia.

Keywords: Hypertension, Blood pressure, Epidemiology, Controlled hypertension, Tunisia

Abstract

The aim of the Epidemiological Trial of Hypertension in North Africa (ETHNA-Tunisia) was to evaluate the prevalence and clinical profile of hypertension in a large sample of individuals in Tunisia. This was multicenter, epidemiological, cross-sectional study conducted in patients consulting primary care physicians in Tunisia. Mean age of 5802 individuals was 49.6 ± 16.3 years. The total prevalence of hypertension was 47.4% (adjusted for age: 26.9%). Control of hypertension was only 37.1%. Hypertension may also be underdiagnosed and ineffectively treated. Greater awareness and improved management of hypertension and cardiovascular risks are needed in Tunisia.

1. Introduction

Epidemiological transition occurring in the majority of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is characterized by an increased exposure to risk factors driven by changes in diet, physical activity, and environment.1 The result has been an increase in the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors including hypertension, raising concerns about the potential development of an epidemic of cardiovascular disease in developing countries.

One region that has seen considerable economic development over the past few decades is North Africa. However, a good understanding of the current levels of hypertension and cardiovascular disease risks in the region, and especially Tunisia, is lacking. Some data from studies in specific cities or for specific ages are available on the prevalence of hypertension. Data collected from 8000 adults from Tunisia, estimated the prevalence of hypertension to be 30.6%.2 Recently, in North Africa, a cross-sectional study Epidemiological Trial of Hypertension in North Africa (ETHNA) conducted in 28,000 patients consulting primary care physicians in Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco reported a high prevalence of hypertension (45.4%).3 In this paper, we presented the results about hypertension from Tunisian patients’ data.

2. Methods

This was a national, multicenter, epidemiological, cross-sectional study conducted in patients attending primary care physicians in Tunisia. The sample size was calculated based on an estimated prevalence of hypertension of 30%. With a risk of error of 1%, a difference of imprecision of 1.0% and a cluster effect of 2, the number to be included in the study was rounded to 6000 participants. Data were collected by participating primary care physicians using a standardized questionnaire. Patients were also clinically examined and measurements were taken for weight, height, waist circumference and blood pressure (BP). BP of participants was measured by a trained physician with the mercury sphygmomanometer. The participants were required to rest in a seated position for at least 5 min before the measurement. Two BP measurements were planned: one after 5 min of rest and the second following a further 2-min rest after the completion of the first measurement. When possible, BP measurements were recorded as the mean of the two measurements. Hypertension was identified according to the criteria of the European Society of Hypertension and the European Society of Cardiology (ESH/ESC) guidelines.4 Details of material and methods was previousely published.3

Descriptive analyses were used to determine the crude prevalence of hypertension over the whole sample. In addition, age- and sex-adjusted rates were calculated by multiplying the age- and sex-specific rate for each age group in the study population by the appropriate weights from a standard population.5 Data were analyzed by using binary logistic regression models to evaluate possible risk factors associated with the presence of hypertension. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were estimated. A test was considered significant when p < 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

The characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 49.6 ± 16.3 years, and almost 28% of participants were older than 60 years of age. Nearly 54% of the participants were female and 79% of participants lived in urban area.

Table 1.

Proportions of individuals with a history of hypertension, control of hypertension and newly detected hypertension according to socio-demographic characteristics and personal medical profile.

| Category | Total n (%) |

History of hypertension (HH) |

Control of hypertension (CH) |

Newly detected hypertension (NH) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total of individuals | Individuals with HH (%) | Total of individuals | Individuals with CH (%) | Total of individuals | Individuals with NH (%) | ||

| Age | |||||||

| <50 years | 2921 (50.2) | 2883 | 27.8*** | 326 | 36.5 | 2557 | 14.6*** |

| 50–59 years | 1279 (21.9) | 1265 | 45.8 | 579 | 38.5 | 686 | 28.4 |

| ≥60 years | 1627 (27.9) | 1616 | 65.7 | 1062 | 35.5 | 554 | 35.2 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 3120 (53.7) | 3087 | 37.2*** | 1147 | 36.7 | 1940 | 19.5 |

| Male | 2693 (46.3) | 2663 | 30.8 | 820 | 36.2 | 1843 | 20.7 |

| Area of habitation | |||||||

| Rural | 1183 (21.0) | 1171 | 32.5 | 381 | 32.5 | 790 | 24.4*** |

| Urban | 4443 (79.0) | 4392 | 34.9 | 1532 | 37.5 | 2860 | 18.9 |

| Education | |||||||

| Illiterate | 1100 (19.2) | 1087 | 56.9*** | 618 | 31.6** | 469 | 32.8*** |

| Elementary school | 1219 (21.3) | 1209 | 41.9 | 507 | 37.9 | 702 | 23.5 |

| Secondary school | 2168 (37.9) | 2143 | 26.6 | 571 | 37.1 | 1572 | 18.4 |

| University graduate | 1237 (21.6) | 1222 | 19.6 | 240 | 45.8 | 982 | 14.5 |

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Ex-smoker | 588 (10.1) | 584 | 50.2*** | 288 | 39.6 | 283 | 30.4*** |

| Current smoker | 1208 (20.8) | 1194 | 23.3 | 274 | 32.5 | 909 | 21.8 |

| Non-smoker | 4023 (69.1) | 3978 | 35.2 | 1381 | 37.5 | 2556 | 18.8 |

| Abdominal obesity | |||||||

| Yes | 2419 (41.1) | 2392 | 46.8*** | 1105 | 34.8* | 1273 | 28.9*** |

| No | 3197 (58.9) | 3164 | 24.8 | 771 | 39.9 | 2380 | 15.5 |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||||||

| Non-diabetic | 4646 (80.8) | 4588 | 27.4*** | 1236 | 39.2* | 3332 | 18.7*** |

| Type 1 | 907 (15.8) | 902 | 62.3 | 555 | 33.7 | 340 | 30.9 |

| Type 2 | 196 (3.4) | 196 | 67.3 | 132 | 32.6 | 64 | 39.1 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | |||||||

| Yes | 1187 (20.7) | 1176 | 65.1*** | 755 | 35.0 | 0411 | 36.7*** |

| No | 4535 (79.3) | 4483 | 26.4 | 1165 | 38.5 | 3301 | 17.9 |

| Body mass indexa | |||||||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 113 (1.9) | 113 | 8.8*** | 10 | 50.0* | 0103 | 06.8*** |

| Normal (18.5 to <25 kg/m2) | 2177 (37.0) | 2156 | 21.3 | 455 | 42.4 | 1697 | 12.8 |

| Overweight (25 to <30 kg/m2) | 2007 (34.1) | 1983 | 37.9 | 743 | 35.9 | 1232 | 23.6 |

| Obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) | 1507 (26.0) | 1497 | 48.5 | 715 | 34.0 | 771 | 31.9 |

p < 0.05.

p ≤ 0.01.

p ≤ 0.001.

World Health Organization classification.

Among the 5802 participants surveyed, 2750 individuals had hypertension, an overall crude prevalence of 47.4% [95% confidence interval (CI) 46.1%-48.7%]. Of these individuals, 1981 (72.0%) had a history of hypertension and 769 (28.0%) were detected with hypertension at the time of the study assessment. When adjusted for age and sex, the overall prevalence of hypertension was 26.9% [95% CI 26.4%-27.4%; 25.4% in men (95% CI 24.6%-26.1%) and 28.4% in women (95% CI 27.7%-29.1%)]. The ETHNA-Tunisia data shows that the prevalence of hypertension is high in population consulting general medicine.

The overall worldwide prevalence of hypertension was estimated at 26.4% of the adult population.6 Results from our study, suggest an overall age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension to be 26.9% which is similar to that reported in the USA (28%) and Canada (27%) and was found a substantially lower compared with the European countries (Sweden, 38%; England, 42%; Spain, 47%; and Germany, 55%).6 Ethnicity has played a role in the prevalence of hypertension in certain geographical areas. Epidemiologic studies demonstrating higher prevalence of hypertension among African Americans relative to those from continental Africa.7 In Arab countries, hypertension prevalence varied widely between and within countries.8 For national studies, hypertension prevalence ranged from 27.6% in Palestine9 to 41.5% in Oman.10 In the Tunisian context, data collected from 957 individuals in 1995–1996 in the city of Sousse, estimated the prevalence of hypertension to be 28.9%,11 while a 2004–2005 national study in over 8000 adults (aged 35–70 years) reported a prevalence of 30.6%.2

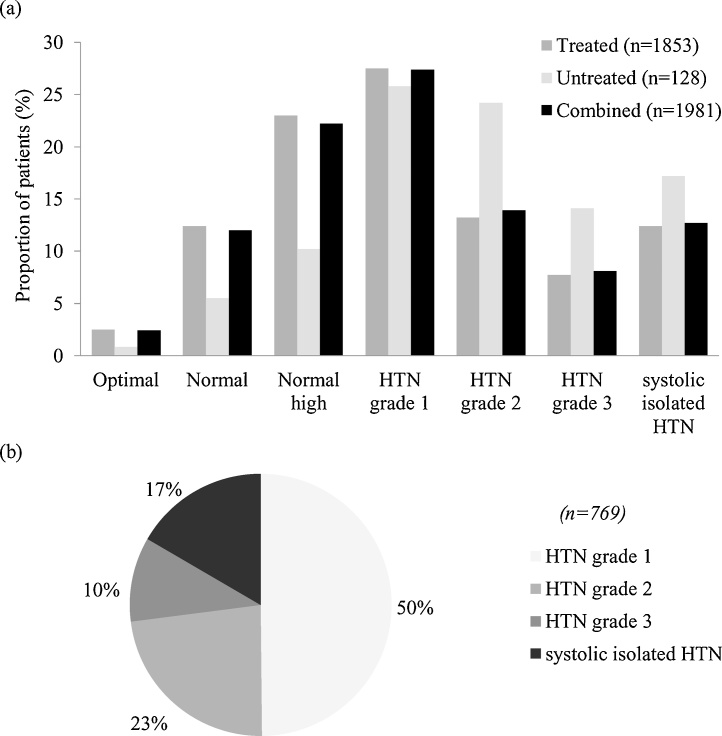

Fig. 1 present hypertension severity in patients with a history of hypertension and newly detected hypertension. In total, 14.4% of patients had either normal or optimal blood pressure (BP) at the time of the study visit. Hypertension was more common in illiterate participants, women, ex-smokers, individuals who had abdominal or central obesity, diabetes and hypercholesterolemia.

Fig. 1.

Hypertension severity in patients with (a) a history of hypertension and (b) newly detected hypertension. Data presented are percentage of patients within each group. (HTN: hypertension).

Among 3834 individuals without a history of hypertension, 769 participants (20.0%) were detected with hypertension at the time of the study visit. Newly detected hypertension was higher in aged individuals, illiterate, people from rural areas, patients with diabetes, high cholesterol and obesity.

History of hypertension was more common in women than in men (37.2% vs 30.8%). This could be related to the fact that around half of the women in the study were postmenopausal. However, links between cardiovascular risk and postmenopausal status have been an area of debate, and it may be argued that any increase in the prevalence of hypertension in these women could be attributed to their age and sex hormones.12

The results of binary logistic regression analysis, including OR for each of the socio-demographic factors, clinical data and family history of hypertension are presented in Table 2. Significant risk factors were related to age, education, residency, obesity, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia and family history of hypertension.

Table 2.

Significant independent variables (risk factors) for hypertension according to binary logistic regression analysis (final model).

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years old | <0.0001 | ||

| <50 | – | – | 1 |

| 50–59 | 3.19 | 2.69–3.78 | <0.0001 |

| ≥60 | 9.33 | 7.63–11.42 | <0.0001 |

| Education level | <0.0001 | ||

| University graduate | – | – | 1 |

| Secondary school | 1.14 | 0.94–1.38 | 0.185 |

| Elementary school | 1.57 | 1.26–1.96 | <0.0001 |

| Illiterate | 1.65 | 1.25–2.17 | <0.0001 |

| Area of habitation (urban vs rural) | 1.30 | 1.07–1.58 | 0.008 |

| Abdominal obesity (yes vs no) | 1.22 | 1.01–1.49 | 0.043 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 vs <30) | 1.66 | 1.47–1.88 | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus (yes vs no) | 1.76 | 1.45–2.14 | <0.0001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia (yes vs no) | 2.49 | 2.05–3.01 | <0.0001 |

| Family history of hypetension (yes vs no) | 2.43 | 2.08–2.83 | <0.0001 |

Hypertension prevalence was higher in olders and like in many studies; age represents a significant risk factor for hypertension.8 In our study and several other studies, it was found that obesity is a strong risk factor for the development of hypertension.8, 13, 14 Therefore, especially physicians from primary care centers should pay attention to the BMI of their hypertensive patients and encourage them to lose weight. Also, hypertension prevalence decreased in higher education consultants as proved in several studies8, 15, 16, 17 which was not demonstrated in the large study conducted by Ben Romdhane et al in the year 2004–2005.2

Generally, hypertension prevalence is significantly high in subjects with diabetes, hypercholesterolemia and familiy history of hypertension.2 In our study, hypercholesterolemia (OR = 2.49) and familiy history of hypertension (OR = 2.43) were also principal risk factors for development of hypertension similarly in other studies.2, 15, 16, 17, 18 Therefore, controling these risk factors would help the cardiovascular complications.

The results of this study indicate that patients with hypertension may not be receiving optimal treatment for achieving adequate BP control. Although 93.5% of patients with a history of hypertension were prescribed antihypertensive medication and only 37.1% of patients had controlled hypertension. Therefore, there is an urgent need to implement innovative strategies to improve hypertension treatment and control in Tunisia and generally in LMICs.

In conclusion, this study indicates that hypertension and cardiovascular risk factors are highly prevalent in Tunisia. Undoubtedly, awareness of hypertension and establishment of healthy lifestyles are encouraged.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all subjects who participated in the study. We highly acknowledge the contribution by all participating doctors. This work was funded by Novartis Pharma Morocco, SA.

References

- 1.Modesti P.A., Perruolo E., Parati G. Need for better blood pressure measurement in developing countries to improve prevention ofcardiovascular disease. J Epidemiol. 2015;25(2):91–98. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20140146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben Romdhane H., Ben Ali S., Skhiri H. Hypertension among Tunisian adults: results of the TAHINA project. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:341–347. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nejjari C., Arharbi M., Chentir M.T. Epidemiological Trial of Hypertension in North Africa (ETHNA): an international multicentre study in Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. J Hypertens. 2013;31:49–62. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835a6611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mancia G., De Backer G., Dominiczak A. 2007 Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) J Hypertens. 2007;25:1105–1187. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3281fc975a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.2010. Université De Sherbrooke Canada Perspective Monde, Pyrmamides Des âges. [Availalable from: http://perspective.usherbrooke.ca/bilan/servlet/BMPagePyramide?codePays=TUN Accessed 15.12.16] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cifkova R., Fodor G., Wohlfahrt P. Changes in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in high-, middle-, and low-Income countries: an update. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2016;18:62. doi: 10.1007/s11906-016-0669-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ortega L.M., Sedki E., Nayer A. Hypertension in the African American population: a succinct look at its epidemiology, pathogenesis, and therapy. Nefrologia. 2015;35(2):139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.nefro.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tailakh A., Evangelista L.S., Mentes J.C., Pike N.A., Phillips L.R., Morisky D.E. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, and control in Arab countries: a systematic review. Nurs Health Sci. 2014;16(1):126–130. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khdour M.R., Hallak H.O., Shaeen M., Jarab A.S., Al-Shahed Q.N. Prevalence awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in the Palestinian population. J Hum Hypertens. 2013;27(10):623–628. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2013.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abd El-Aty M.A., Meky F.A., Morsi M.M., Al-Lawati J.A., El Sayed M.K. Hypertension in the adult Omani population: predictors for unawareness and uncontrolled hypertension. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2015;90(3):125–132. doi: 10.1097/01.EPX.0000470547.32952.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghannem H., Hadj Fredj A. Epidemiology of hypertension and other cardiovascular disease risk factors in the urban population of Soussa, Tunisia. East Mediterr Health J. 1997;3:472–479. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandberg K., Ji H. Sex differences in primary hypertension. Biol Sex Differ. 2012;3:7. doi: 10.1186/2042-6410-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon S.J., Kim D.H., Nam G.E. Prevalence and control of hypertension and albuminuria in South Korea: focus on obesity and abdominal obesity in the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2012. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e111179. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landsberg L., Aronne L.J., Beilin L.J. Obesity-related hypertension: pathogenesis, cardiovascular risk, and treatment?a position paper of the The Obesity Society and The American Society of Hypertension. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21(1):8–24. doi: 10.1002/oby.20181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park C.S., Ha K.H., Kim H.C., Park S., Ihm S.H., Lee H.Y. The association between parameters of socioeconomic status and hypertension in Korea: the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(12):1922–1928. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.12.1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei Q., Sun J., Huang J. Prevalence of hypertension and associated risk factors in Dehui City of Jilin Province in China. J Hum Hypertens. 2015;29(1):64–68. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2014.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu M., Wan Y., Yu L. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension and associated risk factorsamong adults in Xi'an, China: a cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(34):e4709. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pessinaba S., Mbaye A., Yabeta G.A. Prevalence and determinants of hypertension and associated cardiovascular risk factors: data from a population-based, cross-sectional survey in Saint Louis, Senegal. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2013;24(5):180–183. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2013-030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]