Abstract

We compared one-year clinical outcomes of different drug eluting stents (DES) used in a prospective observation registry maintained in two hospitals over three years. The primary endpoint was combination of all-cause mortality, stent thrombosis and revascularization. There was no significant difference among different DES. We grouped DES into well-evaluated Imported DES (Imported group), which used to be expensive prior to price control and economical Indian DES (Indigenous group) that lack supportive clinical trials. One-year follow-up data was available in 99% of Indigenous group (n=1856) and 98.5% of Imported group (n = 1539). After propensity score matching, there were 1310 matched pairs. There was no significant difference between two groups in the primary end-point or each of the components.

Key words: Drug eluting stents, India

1. Introduction

When the government of India had regulated the prices of coronary stents, cardiologists wondered if all drug eluting stents (DES) can be equated in terms of their clinical performance. Multiple randomized controlled trials (RCT) are available that proved the safety and efficacy data of different Imported DES and they were found to be more or less equally effective. Indigenously manufactured and economical Indian DES lack such supportive data.1 Cardiologists as well as patients used to face dilemma whether to opt for expensive and well evaluated Imported DES or economical but less well evaluated Indian DES. In the absence of RCT data, we reviewed our registry data to compare one-year clinical performance of different DES that were used in our hospitals.

2. Methods

We have been maintaining a prospective registry of all percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) done in two CARE hospitals located in Hyderabad. Institutional Ethics Committee had approved the registry and we enrolled all subsequent patients who underwent coronary intervention after obtaining their informed written consent. Treating cardiologists chose the type of DES based on patient’s affording capacity and availability on shelf. In general, patients with financial constraints received Indigenous DES while affording patients received Imported DES.

Indigenous DES included Release R, Premier, Pristine (all manufactured by Relisys Medical Devices), Abluminus (Envision Scientific), Biomime (Meryl Life Sciences) and Yukon Choice (Translumina Therapeutics). Imported DES consisted of DES manufactured outside India and included Xience family of stents (Abbott Vascular), Promus family (Boston Scientific), Endeavour family (Medtronics Vascular) and Biomatrix (Biosensors International). Since the numbers of patients were variable and small for some DES categories, we grouped the patients receiving Indigenous DES as one group and Imported DES as another for the purpose of analysis.

Research coordinators collected clinical details during index hospitalization and clinical events till the end of one year following stent implantation during follow-up clinic visits or telephonically. Treating consultants verified this data. Primary outcome was defined as a composite of all-cause mortality, stent thrombosis, and target vessel revascularization. Individual components are considered as secondary endpoints. Since events were not adjudicated, we counted all deaths as cardiac except one due to accident. Stent thrombosis included definite and probable stent thrombosis as defined by academic research consortium.2 Stroke and non-target vessel revascularization were excluded from primary endpoint.

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as counts and percentages. The data were compared using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test for continuous variables, and χ2 test for categorical variables. R software was used for propensity score matching. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each event and a p value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

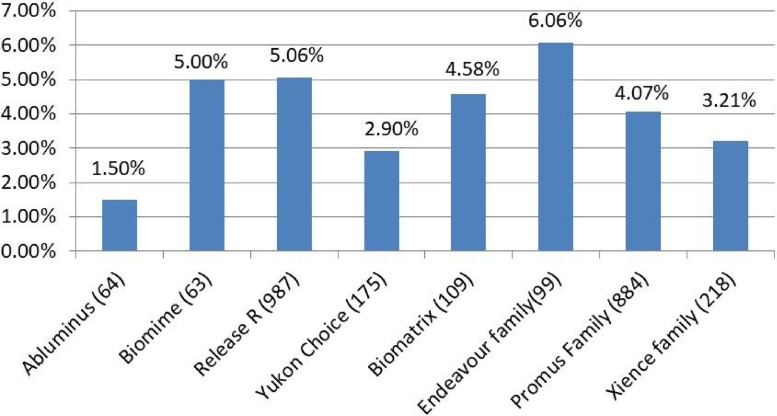

During the study period from 1st January 2013 to 31st December 2015, a total of 5436 patients underwent PCI with stent implantation. Patients who received bare metal stents (BMS), Taxus and Absorb stents and more than one kind of stent were excluded from the analysis. One-year follow-up data was available for 99% in Indigenous group (n = 1856) and 98.5% in Imported group (n = 1539). Fig. 1 shows the number of patients who received different DES.

Fig. 1.

One year combined adverse event rates for different stents.

Total events are expressed as percentages. Number within parenthesis after each stent category indicates the number of patients implanted with that stent. None of the differences are statistically significant.

As shown in Table 1, there were significant differences in baseline characteristics between two groups. Indian DES group patients were younger. Tobacco usage was found to be more prevalent in them. More often they presented with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and underwent primary angioplasty. They had lower left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Imported DES group had more diabetic patients.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic, clinical and angiographic characteristics of patients before and after Propensity Score Matching.

| Parameter | Before Propensity Score matching |

p Value | After Propensity Score matching |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imported DES (1539) | Indian DES (1856) | Imported DES (1310) | Indian DES (1310) | |||

| Age years (mean ± SD). | 57.9 (10.2) | 55.56 (10.5) | <0.001 | 57 (10.1) | 56.9 (10.1) | 0.664 |

| Male Sex − no. (%) | 1246 (80.1%) | 1435 (77.3%) | <0.05 | 1028 (78.4%) | 1039 (79.3%) | 0.632 |

|

LVEF (%)α (Mean ± SD) |

55.5 (11.1) | 53.86 (11.6) | <0.001 | 54.9 (11.2) | 55 (11.3) | 0.802 |

| Primary PCI£ | 313 (20.3%) | 498 (26.8%) | <0.001 | 294 (22.4%) | 270 (20.6%) | 0.274 |

| ACS# | 873 (56.8%) | 1229 (66%) | <0.001 | 800 (61.1%) | 798 (60.9%) | 0.968 |

| Stable Angina | 246 (16%) | 203 (11%) | <0.001 | 170 (13.3%) | 166 (12.7%) | 0.861 |

| Diabetes Mellitus − no (%) | 717 (46.6%) | 778 (41.7%) | <0.01 | 600 (45.8%) | 577 (44%) | 0.388 |

| Hypertension − no (%) | 881 (57.2%) | 1049 (56.5%) | 0.75 | 750 (57.3%) | 749 (57.2%) | 1.0 |

| Tobacco consumption − no. (%) | 203 (13.1%) | 373 (20%) | <0.001 | 196 (15%) | 198 (15.1%) | 0.956 |

|

1 vessel disease§ – no. (%) |

769 (50%) | 992 (53.4%) | <0.05 | 682 (52.1%) | 664 (50.7%) | 0.506 |

|

2 vessel disease§ – no. (%) |

524 (34%) | 651 (35%) | 0.72 | 452 (34.5%) | 479 (36.6%) | 0.289 |

|

3 vessel disease§ – no. (%) |

246 (16%) | 213 (11.5%) | <0.001 | 176 (13.4%) | 167 (12.7%) | 0.643 |

|

LAD$ - no. (%) |

841 (54.6%) | 991 (53.3%) | 0.578 | 718 (54.8%) | 708 (50.4%) | 0.724 |

Foot Notes: This table shows the difference in baseline characteristics between Indian and Imported DES groups. Before propensity score matching, there are significant differences between the two groups in most of the parameters. After propensity score matching, there is no significant difference between the two groups and they became comparable.

α LVEF is Left ventricular ejection fraction as measured during hospital admission.

£ Primary PCI − coronary intervention was done as an emergency primary procedure for ST elevation myocardial Infarction.

# ACS acute coronary syndrome includes ST elevation and non ST elevation myocardial infarction and unstable angina.

§ Number of vessels diseased in the patient.

$ LAD indicates that Left Anterior Descending Artery is the culprit vessel that was intervened.

P value less than 0.05 is considered significant.

Propensity score matching was done to adjust for selection bias. After propensity score matching, there were 1310 matched pairs with no significant difference in baseline variables (Table 1). Further analysis was done in this matched cohort.

About 95% of Indigenous DES group and 97% of Imported DES group were drug compliant. Twenty-one of the 84 in Indigenous DES group and 19 of the 45 in Imported DES group who were less compliant had events.

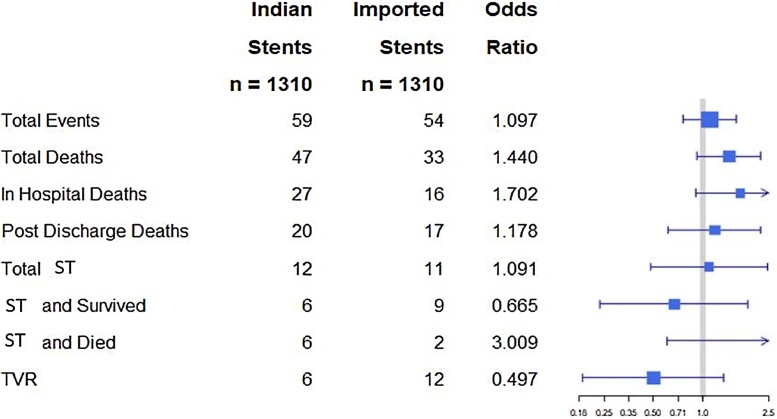

There was no significant difference in primary endpoint among different DES compared individually to one another (Fig. 1). In unadjusted analysis, 83 patients in the Indigenous DES group and 57 in the Imported DES group met primary endpoint (4.63% vs 3.37%, respectively, p = .263). As shown in Fig. 2, after propensity score matching, we found no significant difference in any of the outcomes between Indigenous and Imported DES groups. Since ‘Release R™’ stent accounted for 76% (1351) of all Indigenous DES, we compared its outcomes data with different other DES and there was no statistically significant difference in any of the endpoints.

Fig. 2.

Forrest Plot comparing Indian DES with Imported DES for different adverse events over one year.

All the horizontal lines cross the median line suggesting that there is no statistically significant difference between both the groups either in combined end point or individual components.

ST Stent Thrombosis.

TVR Target Vessel Revascularization.

4. Discussion

Our data suggests that there may not be significant difference in clinical outcomes between different DES. However, no definite conclusion can be drawn given the small and variable numbers of different DES. One-year event rates with different DES used in this registry are comparable to published reports.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Compared to some of the published reports, total one-year mortality in this registry was relatively higher than revascularization rate. This, we think, reflects higher proportion of sick patients with acute myocardial infarction. Stent thrombosis rates in both groups were same and were in line with other published reports. Grouping the DES as Indigenous and Imported is not scientific but it was done to reflect the cost differences, which is an important aspect of health care delivery. Different clinical trials found all Imported DES except Taxus and Absorb to be neither inferior nor superior to one another.9, 10, 11, 12 Within each family of DES also, there is no demonstrable superiority of later versions over previous versions in terms of clinical outcomes. In clinical practice, all different Imported DES are considered as equally effective and it is the reason for grouping them together. Similarly, total event rates of Indigenous DES of this registry are same as in published reports.13,14 The limitations of this study include that not all DES are represented and there is relatively high proportion of Release R and Promus family of DES. This study does not capture lesion characteristics that could have influenced the selection of the stent and its outcomes. This registry data needs to be confirmed by similar studies from other centers.

5. One-line key message

Indigenously manufactured DES, though lacking good supportive clinical trial data, seem to be comparable with well evaluated but expensive Imported DES in one-year clinical outcomes.

Funding support

This study is supported by Relisys medical Devices, Mangalpally Village, Ibrahimpatnam Mandal, R.R.District, Telangana, India 501510.

Contributor Information

B.K.S. Sastry, Email: bkssastry@hotmail.com.

Krishna Reddy Nallamalla, Email: nkreddy61@gmail.com.

Nirmal Kumar, Email: drnirmal_kumar@yahoo.com.

Deepti Kodati, Email: deepti.kodati@gmail.com.

Rajeev Menon, Email: menon73@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Mishra S., Reddy S.E. The future importance of devices from emerging countries: the butterfly effect. EuroIntervention. 2012;8:887–889. doi: 10.4244/EIJV8I8A134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cutlip D.E., Windecker S., Mehran R. Academic Research Consortium: clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–2351. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen K.Y., Rha S.W., Wang L. One-year clinical outcomes of everolimus- versus sirolimus-eluting stents in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176:583–588. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waksman R., Barbash I.M., Dvir D. Safety and efficacy of the XIENCE V everolimus-eluting stent compared to first-generation drug-eluting stents in contemporary clinical practice. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:1288–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fajadet J., Neumann F.J., Hildick-Smith D. Twelve-month results of a prospective, multicentre trial to assess the everolimus-eluting coronary stent system (PROMUS Element): the PLATINUM PLUS all-comers randomised trial. EuroIntervention. 2017;12:1595–1604. doi: 10.4244/EIJV12I13A262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassese S., Ndrepepa G., Byrne R.A. Outcomes of patients treated with durable polymer platinum-chromium everolimus-eluting stents: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Euro Intervention. 2017;13:986–993. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-16-00871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garg S., Sarno G., Serruys P.W. The twelve-month outcomes of a biolimus eluting stent with a biodegradable polymer compared with a sirolimus eluting stent with a durable polymer. EuroIntervention. 2010;6:233–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iqbal J., Serruys P.W., Silber S. Comparison of zotarolimus- and everolimus-eluting coronary stents: final 5-year report of the RESOLUTE all-comers trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:e002230. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.002230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meredith I.T., Teirstein P.S., Bouchard A. Three-year results comparing platinum-chromium PROMUS element and cobalt-chromium XIENCE V everolimus-eluting stents in de novo coronary artery narrowing (from the PLATINUM Trial) Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:1117–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De la Torre Hernandez J.M., Garcia Camarero T. A real all-comers randomized trial comparing Xience Prime and Promus Element stents. J Invasive Cardiol. 2013;25:182–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone G.W., Midei M., Newman W. Randomized comparison of everolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents: 2-year clinical follow-up from the clinical evaluation of the xience V everolimus eluting Coronary stent system in the treatment of patients with de novo native Coronary artery lesions (SPIRIT) III trial. Circulation. 2009;119:680–686. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.803528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kereiakes D.J., Ellis S.G., Metzger C. 3-Year clinical outcomes with everolimus-Eluting bioresorbable Coronary scaffolds: the ABSORB III trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2852–2862. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xhepa E., Tada T., Cassese S. Safety and efficacy of the Yukon Choice Flex sirolimus-eluting coronary stent in an all-comers population cohort. Indian Heart J. 2014;66:345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jain R.K., Chakravarthi P., Shetty R. One-year outcomes of a BioMime™ Sirolimus-Eluting Coronary Stent System with a biodegradable polymer in all-comers coronary artery disease patients: the meriT-3 study. Indian Heart J. 2016;68:599–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]