Abstract

L-theanine, a natural nonprotein amino acid with a high biological activity, is reported to exert anti-stress properties. An experiment with a 3 × 2 factorial arrangement was conducted to investigate the effects of dietary L-theanine on growth performance and immune function in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-challenged broilers. A total of 432 one-day-old male yellow-feathered broilers were randomly assigned to 3 dietary treatments (control, antibiotic and L-theanine diets) with 2 subgroups of each (6 replicate cages; 12 birds/cage). Birds from each subgroup of the 3 dietary treatments were intra-abdominally injected with the same amount of LPS or saline at 24, 25, 26 d of age. Both dietary L-theanine and antibiotic improved (P < 0.05) the growth performance of birds before LPS injection (d 1 to 21). The effect of dietary L-theanine was better (P < 0.05) than that of antibiotic. Lipopolysaccharide decreased feed intake (FI) and body weight gain (BWG) from d 22 to 28 (P < 0.05), BWG and feed to gain ratio (F:G) from d 29 to 56 (P < 0.05), increased mortality in different growth periods (P < 0.05), elevated the levels of serum cortisol, α1-acid glycoprotein (α1-AGP), interleukin-6 (IL-6) on d 24 and 25 (P < 0.05), reduced immune organ indexes and contents of jejunal mucosal secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA) on d 28 (P < 0.05). The decreased FI and BWG, as well as increased F:G and mortality in LPS-challenged birds, were alleviated by dietary L-theanine or antibiotic from d 29 to 56 and from d 1 to 56. Dietary L-theanine mitigated the elevated serum α1-AGP level on d 25, serum IL-6 concentration on d 24 and 26, and the decreased jejunal mucosal sIgA content on d 28 of the LPS-challenged birds. The results indicated that L-theanine had potential to alleviate LPS-induced immune stress in broilers.

Keywords: L-theanine, Yellow-feathered broilers, Lipopolysaccharide, Immune stress, Growth performance

1. Introduction

The modern broiler industry has been greatly expanding to meet increasing requirement of growing population (Niu et al., 2015). However, various factors, such as pathogenic microorganisms, heavy vaccinations, drug abuse and other external elements in the intensive production system will attack birds to induce the loss of immune homeostasis and trigger immune stress response directly or indirectly (Liu et al., 2015). Under stress, chickens may be vulnerable to suffer from enteric diseases, which will affect their intestine health and growth performance, inflicting huge financial losses to poultry production (Yang et al., 2011, Liu et al., 2014).

Traditionally, utilization of in-feed antibiotics can enhance the animal growth via maintaining intestinal structure and function (Broom, 2018), regulating intestinal flora and controlling gut pathogens (Looft et al., 2014), and direct modulating immune system (Pomorskamól & Pejsak, 2012). Nevertheless, the European Union and some other countries have forbidden the use of antibiotics in livestock feed according to consideration of antibiotics resistance causing negative effects on human health (Huyghebaert et al., 2011). It is reported that regulation of immune system in birds by certain nutrients or antibiotic-free substances appears to be a way to avoid or lower use of antibiotics (Takahashi, 2012). Therefore, development of safe and effective nutritional additives to modulate the immune function is of great significance to protect chickens from immune stress (Liu et al., 2015).

L-theanine, first isolated from green tea leaves in the late 1940s, is a unique natural nonprotein amino acid accounting for more than 50% of the total free amino acids in green tea leaves (Sakato, 1949, Vuong et al., 2011, Mu et al., 2015). Now it is commonly thought that L-theanine is only detected in Camellia sasanqua, camellia japonica, Camellia oleifera and Xerocomus badius (Wen et al., 2012). L-theanine exists in nature with a relatively high biological activity, while synthetic theanine is normally prepared as a racemic mixture of L- and D-forms (Desai et al., 2005). L-theanine is usually used as a therapeutic or medicinal agent and additive in consumer products. Most of studies in the bio-medical field demonstrated that L-theanine had nervous regulation and protection effect (Sumathi et al., 2015), antioxidative properties (Wang et al., 2014), anti-stress response (Kimura et al., 2007), and immune regulation (Kurihara et al., 2013; Li et al., 2016). However, there are limited reports on application of L-theanine in livestock animals.

In the present study, we used lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a potent activator of innate immune response from the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria (Li et al., 2015a), to induce immunological stress in broilers. Then, we investigated the growth performance, blood parameters, immune organ indexes and jejunal mucous secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA) in broilers supplemented with or without L-theanine to clarify the effect of L-theanine on regulation of immunological stress response and growth performance of broilers.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals, management and experimental design

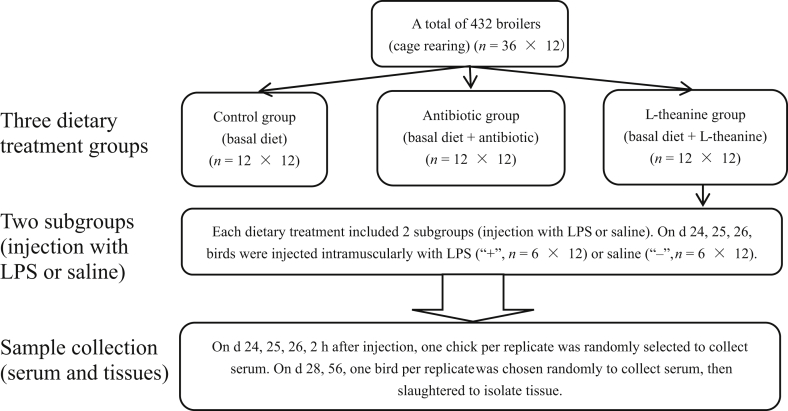

All animal protocols for this study were approved by the Hunan Agricultural University Animal Ethics Committee (Changsha, China). A total of 432 one-day-old male WENS yellow-feathered broilers purchased from a commercial hatchery (WENS Co., Ltd. Guangdong, China) were randomly allotted to 3 dietary groups and each group consisted of 2 subgroups. Each subgroup included 6 replicate cages with 12 birds per cage. There is no difference for the weight of broilers among all cages. Birds in 3 groups received a corn-soybean meal basal diet in mash form or a basal diet supplemented with antibiotics (200 mg/kg colistin sulfa for d 1 to 21, and 150 mg/kg for d 22 to 56) or 800 mg/kg L-theanine. At 24, 25 and 26 d of age, birds from each subgroup of the 3 dietary treatments were intra-abdominally injected with 0.2 mL sterile saline or LPS (Escherischia coli serotype O127:B8; Sigma–Aldrich Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) dissolved in saline at adequate doses of 600 μg/kg BW. Therefore, birds were divided into 1 of 6 treatments (birds fed control, antibiotic, or L-theanine diets; LPS-challenged birds fed basal, antibiotic, or L-theanine diets) (Fig. 1). The corn-soybean basal diet was formulated to satisfy or exceed the NRC (1994) recommendations for the birds during the starter (d 1 to 21) and grower-finisher (d 22 to 56) period (Table 1). L-theanine (≥90% purity measured by HPLC) was gifted from National Research Center of Engineering Technology for Utilization of Functional Ingredients from Botanicals (Changsha, China). The feeding trial was carried out in experimental chicken house affiliated to College of Animal Science and Technology (Changsha, China) for 56 d. All birds were reared in an environmentally controlled with triple-layer wire battery cages (150 cm × 145 cm × 70 cm) and had ad libitum access to feed and fresh water. The room temperature was maintained about 34 °C for the first week and then gradually reduced by 2 °C per consecutive week until it reached 24 °C. Continuous light system was provided in the house and the room relative humidity was kept between 50% and 65%. Bird per cage was weighed at 08:00 on d 1, 22, 29 and 57. Feed intake (FI) on a cage basis was recorded at 21, 28 and 56 d of age to calculate body weight gain (BWG), FI and feed:gain ratio (F:G). Mortality was recorded daily and expressed as percentage.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart for the experimental design. A total of 432 one-day-old male yellow feather broilers were randomly divided into 3 dietary treatment groups with 2 subgroups of each (6 replicate cages; 12 birds/cage) and were fed a basal diet, antibiotic diet and L-theanine diet. Birds from each subgroup of the 3 dietary treatment groups were intra-abdominally injected with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or saline at 24, 25 and 26 d of age.

Table 1.

Ingredients and nutrient levels of the corn-soybean basal diet (air-dry basis).

| Item | d 1 to 21 | d 22 to 56 |

|---|---|---|

| Ingredients, % | ||

| Corn | 59 | 61 |

| Wheat middling and reddog | 3.9 | 4 |

| Soybean meal | 25.4 | 22 |

| Fish meal | 2 | – |

| Soybean oil | 1.8 | 1.4 |

| Cottonseed protein | 4 | 7.8 |

| Dicalcium phosphate | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Limestone | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Sodium chloride | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Premix1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

| Nutrient levels2 | ||

| Metabolizable energy, MJ/kg | 12.42 | 12.31 |

| Crude protein | 21.2 | 20.45 |

| Lysine | 1.22 | 1.11 |

| Methionine | 0.49 | 0.43 |

| Methionine + Cystine | 0.86 | 0.81 |

| Calcium | 0.95 | 0.81 |

| Total phosphorus | 0.64 | 0.58 |

Premix provided per kilogram of complete feed: vitamin A 1,200 IU; vitamin D3 2,500 IU; vitamin E 20 mg; vitamin K3 3.0 mg; vitamin B1 3.0 mg; vitamin B2 8.0 mg; vitamin B6 7.0 mg; vitamin B12 0.03 mg; pantothenic acid 20.0 mg; niacin 50.0 mg; biotin 0.1 mg; folic acid 1.5 mg; Cu 8.0 mg; Fe 100 mg; Mn 100 mg; Zn 75.0 mg; I 0.7 mg; Se 0.4 mg.

Nutrient levels were calculated values.

2.2. Sample collection

One bird per replicate was randomly selected to collect about 5 mL of blood from brachial vein using 5-mL vacuum tubes on d 24, 25 and 26 at 2 h after LPS or saline injection. Serum samples were detached through centrifugation at 2, 000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and then the supernatant was dispensed into 1.5-mL Eppendorf tubes and stored at −20 °C until analyzed. At 28 and 56 d of age, one chick per cage was randomly chosen to collect serum samples according to the above methods, and then slaughtered to isolate the mid-sections of jejunum. The jejunal contents were flushed with saline to scrape the mucosa, which was placed in 1.5-mL Eppendorf tubes and stored at −80 °C for further detection. Besides, the bursa, thymus and spleen of each bird were excised and weighed to calculate the indexes of immune organ with the following formula: Relative organ weight (%) = (Organ weight/Body weight) × 100.

2.3. Measurements of serum index and jejunal mucous sIgA contents

The concentrations of cortisol (CORT), α1-acid glycoprotein (α1-AGP) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) in serum were measured with ELISA kit (Cusabio Biotech Co., Ltd, Wuhan, Hubei, China) according to the manufacturer's manual. In brief, standards or serums were added to the appropriate microtiter plate wells with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated antibody specific to CORT, α1-AGP or IL-1β. The competitive inhibition reaction was launched between with pre-coated CORT, α1-AGP or IL-1β and these in serum. The substrate 3,3,5,5-tetramethyl benzidine solution (TMB) was added to the wells and the color was developed. Samples were arranged in triplicates and the average value of each sample was used for analysis. The absorbance was read at a wavelength of 450 nm by a multiskan spectrum microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific [China], Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) within 5 min after adding the stop solution.

The serum concentration of interleukin-6 (IL-6) was detected with a chicken sandwich ELISA kit. Briefly, IL-6 existed in serum or standards was captured by chicken antibody specific for IL-6 pre-coated onto a microplate. Then, the captured IL-6 was bound to biotin-conjugated antibody labeled with HRP. The addition of substrate TMB triggered a chromogenic enzymatic reaction catalyzed by HRP and the color developed in proportion to the amount of IL-6 in the serum. The OD values were read at 450 nm with a multiskan spectrum microplate spectrophotometer within 5 min after adding the stop solution. The detection range of IL-6 is between 15.6 and 1,000 pg/mL.

The content of jejunal mucous sIgA were measured in accordance with instructions introduced by a competitive inhibition chicken ELISA kit. The principle of the assay is similar with that of CORT, α1-AGP or IL-1β. Mucous samples were vortexed and centrifuged at 4,000 r/min for 10 min. Then, the supernatant was collected and diluted 1:1,000 before the assay. On the basis of the manufacturer, the detection range of sIgA is between 0.234 and 60 μg/mL.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the GLM procedure of SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for a 3 × 2 factorial arrangement: 3 diets (control, antibiotics, L-theanine diets) × 2 immune stress (saline and LPS). The main effects of dietary treatments and immune stress, as well as their interactions were determined. Differences among the treatment mean values were assessed by ANOVA using Duncan's multiple comparisons test. Statistical significance was determined at a probability level of 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Growth performance

As shown in Table 2, birds in L-theanine group had higher FI, BW, and lower F:G than those in control and antibiotic groups (P < 0.05) before LPS challenge (d 1 to 21). Birds injected with LPS appeared a lower FI and BW on d 22 to 28 (P < 0.05), a decline in BW and F:G on d 29 to 56 (P < 0.05), and more mortality in each recorded stage (P < 0.05), when compared with the saline-treated broilers. Dietary L-theanine or antibiotic alleviated the decreased FI and BWG, as well as the increased F:G and mortality in LPS-challenged birds on d 29 to 56 and d 1 to 56. Furthermore, there was an LPS × diet interaction for FI on d 29 to 56 and d 1 to 56 (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Effect of dietary L-theanine on growth performance, mortality of LPS-challenged broilers.

| Item1 | LPS2 | FI, g |

BWG, g |

F:G |

Mortality, % |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d 1 to 21 | d 22 to 28 | d 29 to 56 | d 1 to 56 | d 1 to 21 | d 22 to 28 | d 29 to 56 | d 1 to 56 | d 1 to 21 | d 22 to 28 | d 29 to 56 | d 1 to 56 | d 1 to 21 | d 22 to 28 | d 29 to 56 | d 1 to 56 | ||

| Control | – | 532.3c | 259.5 | 854.3b | 1,632.4c | 221.4cd | 92.5b | 340.3c | 643.7bc | 2.41ab | 2.89 | 2.50b | 2.54ab | 1.56 | 3.00 | 2.78cd | 3.01 |

| + | 552.8bc | 225.4 | 681.9c | 1,473.8d | 226.7c | 76.7d | 235.6d | 549.6d | 2.44a | 2.94 | 2.88a | 2.68a | 1.63 | 13.55 | 8.15a | 17.2 | |

| Antibiotic | – | 566.2b | 300.2 | 1,221.3a | 2,087.6a | 239.7b | 109.6a | 585.1a | 897.6a | 2.36c | 2.74 | 2.08c | 2.35b | 1.41 | 2.47 | 1.21d | 2.67 |

| + | 555.5bc | 229.6 | 1,175.5a | 1,920.6b | 229.8bc | 84.4cd | 558.3ab | 879.3a | 2.41ab | 2.73 | 2.11c | 2.19cd | 1.38 | 9.13 | 3.99c | 8.26 | |

| L-theanine | – | 589.1a | 274.3 | 708.0c | 1,564.7cd | 256.0a | 97.1ab | 353.9c | 691.5b | 2.31cd | 2.82 | 2.00cd | 2.27bc | 1.49 | 2.92 | 1.75d | 2.81 |

| + | 589.9a | 250.4 | 701.3c | 1,548.3cd | 245.5ab | 89.3c | 338.5c | 688.6b | 2.41ab | 2.85 | 2.07c | 2.25c | 1.34 | 8.98 | 4.78b | 6.67 | |

| SEM | 2.561 | 6.852 | 17.518 | 19.598 | 2.114 | 1.800 | 9.363 | 9.804 | 0.023 | 0.078 | 0.043 | 0.031 | 0.297 | 1.551 | 0.671 | 1.372 | |

| P-value | LPS | 0.495 | 0.004 | 0.382 | 0.834 | 0.242 | <0.001 | 0.021 | 0.225 | 0.141 | 0.887 | 0.017 | 0.106 | 0.356 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.017 |

| Diet | <0.001 | 0.355 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.026 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.641 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.608 | 0.097 | 0.025 | 0.089 | |

| Interaction | 0.057 | 0.356 | 0.017 | 0.008 | 0.242 | 0.161 | 0.100 | 0.054 | 0.820 | 0.988 | 0.330 | 0.627 | 0.721 | 0.069 | 0.132 | 0.271 | |

LPS = lipopolysaccharide; FI = feed intake; BWG = body weight gain; F:G = feed to gain ratio.

a–d Within a column, different superscript letters mean significant difference (P < 0.05).

Control, basal diet; antibiotic, basal diet supplemented with antibiotics; L-theanine, basal diet supplemented with L-theanine.

“−” means broilers injected with saline, while “+” means broilers injected with LPS.

3.2. Serum parameters

As shown in Table 3, LPS increased the serum CORT, α1-AGP, IL-6 concentrations on d 24 and 25 (P < 0.05). There was a LPS × diet interaction for serum α1-AGP content (P < 0.05), as evidenced by a mitigation of the elevated serum α1-AGP level in birds injected with LPS on d 25 by L-theanine addition. Dietary antibiotic and L-theanine alleviated the increased serum IL-6 concentration on d 24 and 26 (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Effect of dietary L-theanine on serum indexes of LPS-challenged broilers.

| Item1 | LPS2 | CORT, ng/mL |

α1-AGP, ng/mL |

IL-1β, pg/mL |

IL-6, pg/mL |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d 24 | d 25 | d 26 | d 24 | d 25 | d 26 | d 24 | d 25 | d 26 | d 28 | d 56 | d 24 | d 25 | d 26 | d 28 | d 56 | ||

| Control | – | 5.51 | 8.114 | 9.78 | 1,735.894 | 1,577.359c | 2,297.164 | 47.4 | 55.8 | 54.02 | 48.78 | 53.89 | 30.96c | 29.32 | 28.8b | 26.01 | 27.58cd |

| + | 6.538 | 11.276 | 14.139 | 1,864.182 | 2,014.143b | 1,769.866 | 60.54 | 61.04 | 65.4 | 51.2 | 63.71 | 53.76a | 33.94 | 30.37a | 25.51 | 25.92c | |

| Antibiotic | – | 3.538 | 8.584 | 11.649 | 1,618.703 | 1,547.024c | 1,779.886 | 45.8 | 53.43 | 57.84 | 44.22 | 48.14 | 25.57d | 32.21 | 31.65a | 25.62 | 30.26b |

| + | 9.163 | 10.325 | 5.177 | 2,124.647 | 2,328.470a | 2,101.373 | 71.97 | 59.49 | 64.47 | 49.86 | 55.58 | 44.3b | 37.02 | 30.3a | 25.95 | 31.91b | |

| L-theanine | – | 3.237 | 4.612 | 5.758 | 1,656.433 | 1,439.782c | 1,862.147 | 41.78 | 56.43 | 69.73 | 50.42 | 46.55 | 25.71d | 32.51 | 28.42b | 24.95 | 35.77a |

| + | 4.895 | 8.986 | 5.602 | 1,656.783 | 1,615.188c | 1,834.951 | 51.03 | 53.94 | 70.34 | 59.43 | 68.55 | 25.87d | 37.99 | 27.14b | 26.39 | 32.53ab | |

| SEM | 0.433 | 0.559 | 1.137 | 41.237 | 41.301 | 72.823 | 3.553 | 2.909 | 4.064 | 3.008 | 3.471 | 2.06 | 0.701 | 0.278 | 0.34 | 1.088 | |

| P-value | LPS | 0.005 | 0.013 | 0.742 | 0.017 | <0.001 | 0.6 | 0.032 | 0.619 | 0.452 | 0.354 | 0.072 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.529 | 0.54 | 0.632 |

| Diet | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.099 | 0.117 | 0.002 | 0.593 | 0.368 | 0.901 | 0.541 | 0.565 | 0.689 | 0.011 | 0.1 | <0.001 | 0.989 | 0.031 | |

| Interaction | 0.094 | 0.636 | 0.17 | 0.051 | 0.022 | 0.083 | 0.602 | 0.804 | 0.864 | 0.905 | 0.661 | 0.077 | 0.966 | 0.07 | 0.513 | 0.649 | |

LPS = lipopolysaccharide; CORT = cortisol; α1-AGP = α1-acid glycoprotein; IL-1β = interleukin-1β; IL-6 = interleukin-6.

a–d In the same column, different superscript letters mean significantly difference (P < 0.05).

Control, basal diet; antibiotic, basal diet supplemented with antibiotics; L-theanine, basal diet supplemented with L-theanine.

“−” means broilers treated with saline, while “+” LPS.

3.3. Immune organ index

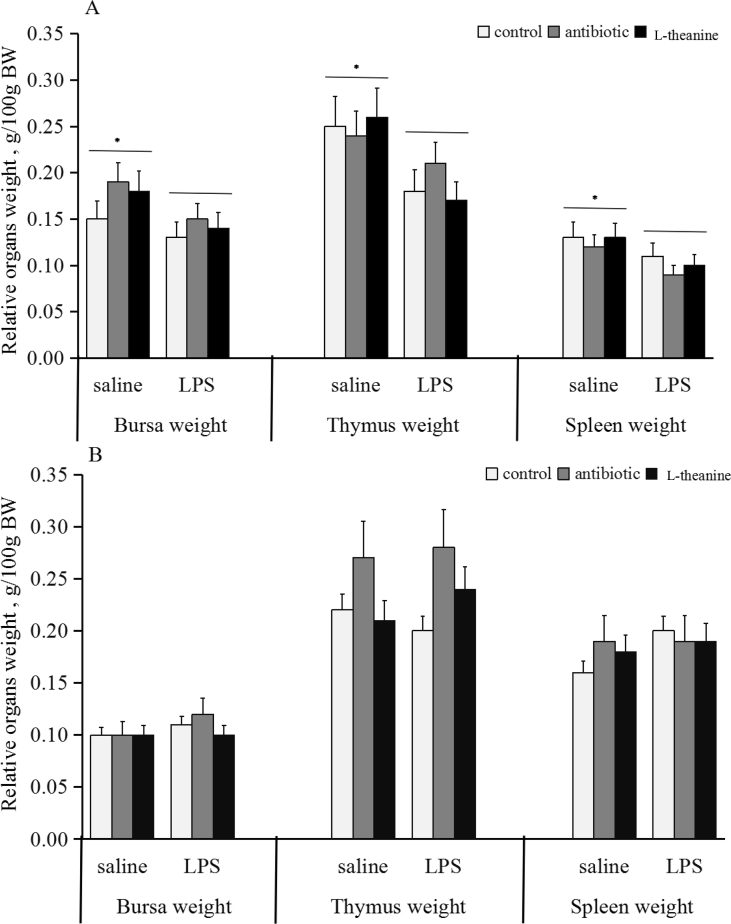

Lipopolysaccharide reduced (P < 0.05) the relative weights of bursa, thymus and spleen in birds on d 28 (Fig. 2A). Dietary antibiotic or L-theanine addition exerted no influence (P > 0.05) on relative organ weights.

Fig. 2.

Relative organ weight in broilers post lipopolysaccharide (LPS) injection. On d 28 (A) or 56 (B), one chick per cage (n = 36) was randomly selected to weight and collect blood, and then slaughtered to isolate immune organs. Relative organ weight was calculated as the organ weight per body weight. “*” represented significant main effect of LPS injection (P < 0.05). Error bars stand for the standard deviation (SD).

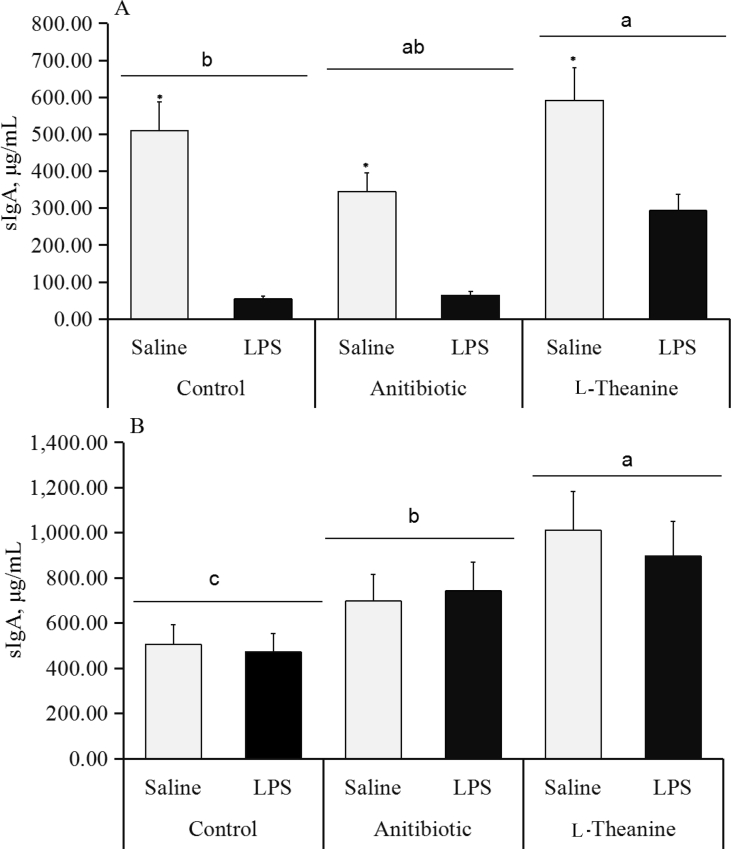

3.4. Jejunal mucous secretory immunoglobulin A content

Jejunal mucosal sIgA content in the LPS-challenged birds decreased (P < 0.05), but L-theanine addition could retard the downtrend on d 28 (Fig. 3A). Lipopolysaccharide did not make a difference in jejunal mucosal sIgA content (P > 0.05), but dietary antibiotic and L-theanine greatly increased (P < 0.05) the level of jejunal mucosal sIgA (Fig. 3B) on d 56.

Fig. 3.

Jejunal mucosal secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA) in broilers post lipopolysaccharide (LPS) injection. On d 28 (A) or 56 (B), one chick per cage (n = 36) was randomly selected to weight and collect blood, and then slaughtered to isolate jejunal mucosal tissue. * represented significant main effect of LPS injection (P < 0.05). Different small letters meant significant main effect of dietary treatment (P < 0.05). Error bars stand for the standard deviation (SD).

4. Discussion

Immune stress induced by LPS resulted in compromised growth performance of broilers (Yang et al., 2011, Haziak et al., 2014, Tan et al., 2014, Fowler et al., 2015, Zhang et al., 2017), which was mainly attributed to reallocation of nutrients. To be specific, diet nutrients were away from growth, but toward processes associated with inflammatory immune response and synthesis of various mediators such as cytokines (Liu et al., 2015, Li et al., 2015b). Besides, immunological stress easily caused intestinal structure injury (Hu et al., 2011, Li et al., 2015a), intestinal digestion and absorption disorder (Feng et al., 2012, Liu et al., 2015) and body metabolic disturbance of animal (Klasing, 2007, Liu et al., 2014). In this study, dietary L-theanine significantly improved growth performance of broilers before LPS challenge, which was similar to the results described previously (Hwang et al., 2008, Wen et al., 2012). Lipopolysaccharide decreased the BWG on d 22 to 28 and on d 29 to 56, which was possibly due to simultaneously compromised FI. Dietary L-theanine alleviated the decreased FI and BWG, as well as increased F:G and mortality in LPS-challenged birds on d 29 to 56 and d 1 to 56, indicating that L-theanine might play a protective role on the growth of infected broilers. These benefits were possibly due to anti-stress and antioxidant characteristics of L-theanine. Maintenance and improvement of anti-stress and antioxidant status in the gastrointestinal tract were good for digestion and absorption of nutrients to promote animal growth. Besides, LPS reduced the immune organ indexes of broilers on d 28 and dietary L-theanine addition had no influence on it, which indicated that the severe immunosuppressive model of broilers was mimicked (Wu et al., 2015, Alizadeh et al., 2016).

The fluctuation of serum CORT and α1-AGP levels could reflect physiological stress of animals. Regulation of stress was closely related to the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) (Koolhaas et al., 1999, Dickerson and Kemeny, 2004). Cortisol is a glucocorticoid hormone secreted by the adrenal cortex, which plays a vital role in relieving stress. Once animals were exposed to external stimulation, the level of serum CORT would rise and nutrients metabolism was strengthened to meet the need of normal physiological function (Nakamura et al., 1998, Liu et al., 2015). As one of acute phase proteins (APP), α1-AGP is mainly synthesized by the liver and particularly participates in immune defensive function. It was reported that the level of serum α1-AGP would increase under acute inflammation (Nakamura et al., 1998). In the present study, the serum CORT and α1-AGP concentrations elevated after LPS challenge, suggesting that broilers suffered from stress and acute inflammation, which provided an evidence for growth inhibition in LPS-challenged broilers. Mitigation the elevated serum α1-AGP level in birds injected with LPS by L-theanine addition on d 25 might be correlated with its anti-stress property. Some investigations showed that L-theanine could pass through the blood–brain barrier to participate in neuromodulation and reduce psychological and physiological stress responses (Juneja et al., 1999, Kimura et al., 2007, Cho et al., 2008, Haskell et al., 2008, Yoto et al., 2012).

Immune stress is often associated with the inflammation response, and cytokines released in the inflammation response could promote metabolism and suppress anabolism of carbohydrate, protein and fat to inhibit growth of animals (Klasing, 1988, Johnson, 1997, Webel et al., 1997, Sijben et al., 2001, Hwang et al., 2008). Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) originated from macrophages were the major cellular messengers initiating metabolic cascade alterations following the innate immune response (Jiang et al., 2015). Lipopolysaccharide was demonstrated to increase pro-inflammatory cytokines secretion and suppress animal growth (Takahashi, 2012, Tan et al., 2014, Li et al., 2015b). Results of the present study results showed that serum IL-1β, IL-6 levels of broilers significantly increased after LPS injection, and then were gradually back to the previous level, which indicated that broilers began to adapt immunological stress and metabolic function gradually recovered to normal. The increased serum IL-6 concentration on d 24 and 26 were alleviated by L-theanine suggested that dietary L-theanine could remit inflammation response.

Gastrointestinal tract of broilers is sensitive to various external antigens, and the intestinal mucosa plays an important role in gut barrier function (Yang et al., 2011). Secretory immunoglobulin A is the main antibody present at mucosal surfaces, which have long been considered as a first line of defense via providing passive immune protection against invading antigens and can protect the intestinal epithelium from enteric pathogens and toxins (Mantis et al., 2011). Immune stress could cause intestinal injury and affect intestinal immune function (Glaser and Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005). Results of the present study research showed that L-theanine addition could retard the decreased jejunal mucosal sIgA contents in the LPS-challenged broilers on d 28 and elevated the level of jejunal mucosal sIgA on d 56. This might be connected with a report by Wen et al. (2012) that L-theanine improved intestinal immune function of broilers via γδT cell-mediated humoral immune regulation.

5. Conclusion

Results from present study indicate that L-theanine could exert a protective role in the growth and immune function of LPS-challenged broilers.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest (201403047), the Hunan Key Scientific and Technological Project (2016NK2124) and the Natural Science Foundation of China (30901035). The authors are grateful to the staff at Department of Animal Nutrition and Feed Science of Hunan Agricultural University for their assistance in conducting the experiment.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

Contributor Information

De-Xing Hou, Email: hou@chem.agri.kagoshima-u.ac.jp.

Xi He, Email: hexi@hunau.edu.cn.

References

- Alizadeh M., Rodriguez-Lecompte J.C., Yitbarek A., Sharif S., Crow G., Slominski B.A. Effect of yeast-derived products on systemic innate immune response of broiler chickens following a lipopolysaccharide challenge. Poult Sci. 2016;95(10):2266–2273. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broom L.J. Gut barrier function: effects of (antibiotic) growth promoters on key barrier components and associations with growth performance. Poult Sci. 2018;97(5):1572–1578. doi: 10.3382/ps/pey021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H.S., Kim S., Lee S.Y., Park J.A., Kim S.J., Chun H.S. Protective effect of the green tea component, L-theanine on environmental toxins-induced neuronal cell death. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29(4):656–662. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai M.J., Gill M.S., Hsu W.H., Armstrong D.W. Pharmacokinetics of theanine enantiomers in rats. Chirality. 2005;17(3):154–162. doi: 10.1002/chir.20144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson S.S., Kemeny M.E. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(3):355–391. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Yang X.J., Wang Y.B., Li W.L., Liu Y., Yin R.Q. Effects of immune stress on performance parameters, intestinal enzyme activity and mRNA expression of intestinal transporters in broiler chickens. Asian Aust J Anim. 2012;25(5):701–707. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2011.11377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler J., Kakani R., Haq A., Byrd J.A., Bailey C.A. Growth promoting effects of prebiotic yeast cell wall products in starter broilers under an immune stress and Clostridium perfringens challenge. J Appl Poult Res. 2015;24(1):66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser R., Kiecolt-Glaser J.K. Stress-induced immune dysfunction: implications for health. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(3):243–251. doi: 10.1038/nri1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskell C.F., Kennedy D.O., Milne A.L., Wesnes K.A., Scholey A.B. The effects of L-theanine, caffeine and their combination on cognition and mood. Biol Psychol. 2008;77(2):113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haziak K., Herman A.P., Tomaszewska-Zaremba D. Effects of central injection of anti-LPS antibody and blockade of TLR4 on GnRH/LH secretion during immunological stress in anestrous ewes. Mediat Inflamm. 2014;2014(3):1–10. doi: 10.1155/2014/867170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Guo Y., Li J., Yan G., Bun S., Huang B. Effects of an early lipopolysaccharide challenge on growth and small intestinal structure and function of broiler chickens. Can J Anim Sci. 2011;91(3):379–384. [Google Scholar]

- Huyghebaert G., Ducatelle R., Van Immerseel F. An update on alternatives to antimicrobial growth promoters for broilers. Vet J. 2011;187(2):182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang Y.H., Park B.K., Lim J.H., Kim M.S., Song I.B., Park S.C. Effects of beta-glucan from paenibacillus polymyxa and L-theanine on growth performance and immunomodulation in weanling piglets. Asian Aust J Anim. 2008;21(12):1753–1759. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Zhang W., Gao F., Zhou G. Effect of sodium butyrate on intestinal inflammatory response to lipopolysaccharide in broiler chickens. Can J Anim Sci. 2015;95(3):389–395. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R.W. Inhibition of growth by pro-inflammatory cytokines: an integrated view. J Anim Sci. 1997;75(5):1244–1255. doi: 10.2527/1997.7551244x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juneja L.R., Chu D.C., Okubo T., Nagato Y., Yokogoshi H. L-theanine - a unique amino acid of green tea and its relaxation effect in humans. Trends Food Sci Technol. 1999;10(6–7):199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K., Ozeki M., Juneja L.R., Ohira H. L-theanine reduces psychological and physiological stress responses. Biol Psychol. 2007;74(1):39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasing K.C. Nutrition and the immune system. Br Poult Sci. 2007;48(5):525–537. doi: 10.1080/00071660701671336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasing K.C. Nutritional aspects of leukocytic cytokines. J Nutr. 1988;118(12):1436–1446. doi: 10.1093/jn/118.12.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koolhaas J.M., Korte S.M., De Boer S.F., Van Der Vegt B.J., Van Reenen C.G., Hopster H. Coping styles in animals: current status in behavior and stress-physiology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1999;23(7):925–935. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara S., Shibakusa T., Tanaka K.A. Cystine and theanine: amino acids as oral immunomodulative nutrients. Springerplus. 2013;2(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Tong H., Yan Q., Tan S., Han X., Xiao W. L-theanine improves immunity by altering TH2/TH1 cytokine balance, brain neurotransmitters, and expression of phospholipase C in rat hearts. Med Sci Monit. 2016;22:662–669. doi: 10.12659/MSM.897077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhang H., Chen Y.P., Yang M.X., Zhang L.L., Lu Z.X. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens supplementation alleviates immunological stress and intestinal damage in lipopolysaccharide-challenged broilers. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2015;208:119–131. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhang H., Chen Y.P., Yang M.X., Zhang L.L., Lu Z.X. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens supplementation alleviates immunological stress in lipopolysaccharide-challenged broilers at early age. Poult Sci. 2015;94(7):1504–1511. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Qin D., Wang X., Feng Y., Yang X., Yao J. Effect of immune stress on growth performance and energy metabolism in broiler chickens. Food Agric Immunol. 2014;26(2):194–203. [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Shen J., Zhao C., Wang X., Yao J., Gong Y. Dietary astragalus polysaccharide alleviated immunological stress in broilers exposed to lipopolysaccharide. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;72:624–632. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looft T., Allen H.K., Cantarel B.L., Levine U.Y., Bayles D.O., Alt D.P. Bacteria, phages and pigs: the effects of in-feed antibiotics on the microbiome at different gut locations. ISME J. 2014;8(8):1566–1576. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantis N.J., Rol N., Corthesy B. Secretory IgA's complex roles in immunity and mucosal homeostasis in the gut. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4(6):603–611. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu W., Zhang T., Jiang B. An overview of biological production of L-theanine. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33(4):335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K., Mitarai Y., Yoshioka M., Koizumi N., Shibahara T., Nakajima Y. Serum levels of interleukin-6, alpha1-acid glycoprotein, and corticosterone in two-week-old chickens inoculated with Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide. Poult Sci. 1998;77(6):908–911. doi: 10.1093/ps/77.6.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Z.Y., Min Y.N., Wang J.J., Wang Z.P., Wei F.X., Liu F.Z. On oxidation resistance and meat quality of broilers challenged with lipopolysaccharide. J Appl Anim Res. 2015;44(1):215–220. [Google Scholar]

- NRC . 9th ed. Natl. Acad. Press; Washington, DC: 1994. Nutrient requirements of poultry. [Google Scholar]

- Pomorskamól M., Pejsak Z. Effects of antibiotics on acquired immunity in vivo - current state of knowledge. Pol J Vet Sci. 2012;15(3):583–588. doi: 10.2478/v10181-012-0089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakato Y. The chemical constituents of tea: III. A new amide theanine. Nippon Nogeik Kaishi. 1949;23:262–267. [Google Scholar]

- Sijben J.W., Schrama J.W., Parmentier H.K., van der Poel J.J., Klasing K.C. Effects of dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids on in vivo splenic cytokine mRNA expression in layer chicks immunized with Salmonella typhimurium lipopolysaccharide. Poult Sci. 2001;80(8):1164–1170. doi: 10.1093/ps/80.8.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumathi T., Shobana C., Thangarajeswari M., Usha R. Protective effect of L-theanine against aluminium induced neurotoxicity in cerebral cortex, hippocampus and cerebellum of rat brain-histopathological, and biochemical approach. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2015;38(1):22–31. doi: 10.3109/01480545.2014.900068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K. Effect of a cultures of aspergillus oryzae on inflammatory response and mRNA expression in intestinal immune-related mediators of male broiler chicks. J Poult Sci. 2012;49(2):94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Tan J., Liu S., Guo Y., Applegate T.J., Eicher S.D. Dietary L-arginine supplementation attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response in broiler chickens. Br J Nutr. 2014;111(8):1394–1404. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513003863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuong Q.V., Bowyer M.C., Roach P.D. L-Theanine: properties, synthesis and isolation from tea. J Sci Food Agric. 2011;91(11):1931–1939. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Zhang L., Wang S., Shi S., Jiang Y., Li N. 8-C N-ethyl-2-pyrrolidinone substituted flavan-3-ols as the marker compounds of Chinese dark teas formed in the post-fermentation process provide significant antioxidative activity. Food Chem. 2014;152(2):539–545. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.10.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webel D.M., Finck B.N., Baker D.H., Johnson R.W. Time course of increased plasma cytokines, cortisol, and urea nitrogen in pigs following intraperitoneal injection of lipopolysaccharide. J Anim Sci. 1997;75(6):1514–1520. doi: 10.2527/1997.7561514x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen H., Wei S.L., Zhang S.R., Hou D.X., Xiao W.J., He X. Effects of L-theanine on performance and immune function of yellow-feathered broilers. Chin J Anim Nutr. 2012;24(10):1946–1954. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q.J., Wang Q.Y., Wang T., Zhou Y.M. Effects of clinoptilolite (zeolite) on attenuation of lipopolysaccharide-induced stress, growth and immune response in broiler chickens. Ann Anim Sci. 2015;15(5):681–697. [Google Scholar]

- Yang X.J., Li W.L., Feng Y., Yao J.H. Effects of immune stress on growth performance, immunity, and cecal microflora in chickens. Poult Sci. 2011;90(12):2740–2746. doi: 10.3382/ps.2011-01591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoto A., Motoki M., Murao S., Yokogoshi H. Effects of L-theanine or caffeine intake on changes in blood pressure under physical and psychological stresses. J Physiol Anthropol. 2012;31(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1880-6805-31-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P.F., Shi B.L., Su J.L., Yue Y.X., Cao Z.X., Chu W.B. Relieving effect of Artemisia argyi aqueous extract on immune stress in broilers. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2017;101(2):251–258. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]