Abstract

This study evaluates 5-year data from the NRG Oncology RTOG 0236 trial on the effects of sterotactic body radiation therapy in patients with inoperable stage I non–small cell lung cancer.

In 2010, NRG Oncology published the initial results (3-year data) of their multicenter, single-arm, phase 2 NRG Oncology RTOG 0236 trial using sterotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) to achieve a potent dose in patients with medically inoperable, clinically staged early lung cancer.1 Despite its rapid acceptance as a standard treatment, the implementation of SBRT into clinical practice has been incomplete.2 Patients enrolled in the NRG Oncology RTOG 0236 trial continued to be followed up per protocol for tumor control, toxic effects, and survival.3 In this report, we describe 5-year results specifically to understand how potential late events may influence the utility of SBRT for this frail population.

Methods

Detailed eligibility criteria are described in the previous report.1 The prescribed dose was 54 Gy in 3 fractions. Patients were followed up every 3 months during years 1 and 2 post treatment, then every 6 months until 4 years post treatment, and then yearly.3 Tumor measurements at each follow-up were carried out using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors.4 The study was approved by institutional review boards at each of the 8 centers that enrolled patients (Washington University in St Louis, St Louis, Missouri; Indiana University, Indianapolis; Princess Margaret Hospital, Toronto, Canada; Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio; University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas; Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; University of Rochester, Rochester, New York; and University of Texas MD Anderson, Houston). All enrolled patients signed written consent to participate; no financial compensation was given to enrollees.

The primary end point of the study was 2-year actuarial primary tumor control. Data on failure beyond the primary tumor but within the involved lobe were collected separately. Local failure included the combination of primary tumor and involved lobe failure. Regional failure included hilar, mediastinal, and supraclavicular nodal failure. Failures occurring outside of these defined local and regional sites were considered distant failures.

Secondary end points included assessments of treatment-related toxic effects, disease-free survival, and overall survival. The National Cancer Institute’s Common Toxicity Criteria, Version 3.0 was used for grading of adverse events (AEs).5 The details of sample size justification and analyses may be found in the original report.1

Results

Between May 26, 2004, and October 13, 2006, 59 patients were enrolled in the study, 55 of whom were evaluable. Median follow-up for all patients was 48 months. Among 7 patients still living, median follow-up was 86.4 months.

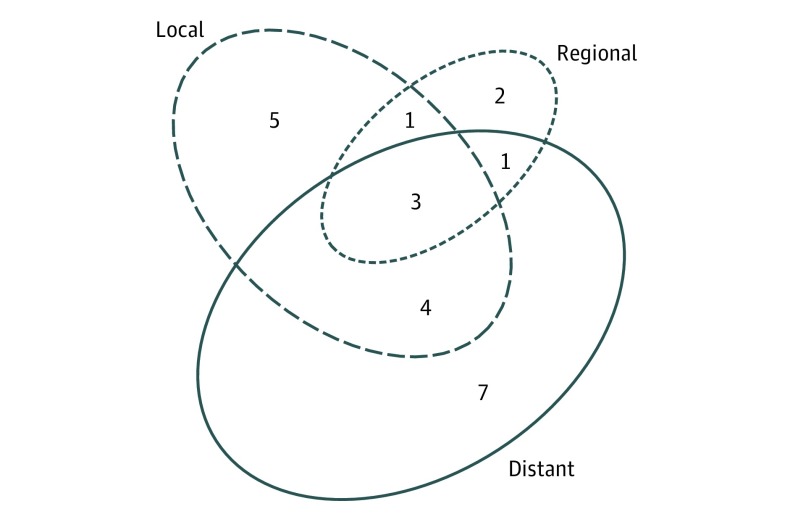

Twenty-three patients showed local, regional, and/or distant progression. Overall patterns of failure are shown in Figure 1. The 5-year recurrence rates are as follows: primary tumor, 7.3% (95% CI, 2.3%-16.3%); primary tumor and involved lobe (local), 20.0% (95% CI, 10.6%-31.6%); regional 10.9% (95% CI, 4.3%-20.9%); local-regional, 25.5% (95% CI, 14.7%-37.6%); and disseminated, 23.6% (95% CI, 13.3%-35.6%). The 5-year rate of disseminated recurrence for patients with T1 category cancer was 18.2% (95% CI, 8.4%-31.0%); for those with T2 category cancer, this rate was 45.5% (95% CI, 15.0%-72.1%). The 5-year rate of disseminated recurrence for squamous histologic findings was 5.9% (95% CI, 0.3%-24.2%); for nonsquamous histologic findings, this rate was 31.6% (95% CI, 17.4%-46.8%).

Figure 1. Patterns of Failure Among 23 Patients Experiencing Progression on NRG Oncology RTOG 0236.

Distant indicates uninvolved lobes of the lung and extrathoracic sites (15 failures); local, primary tumor and involved lobe (13 failures [4 primary tumor and 9 involved lobe]); and regional, hilar or mediastinal lymph nodes (7 failures).

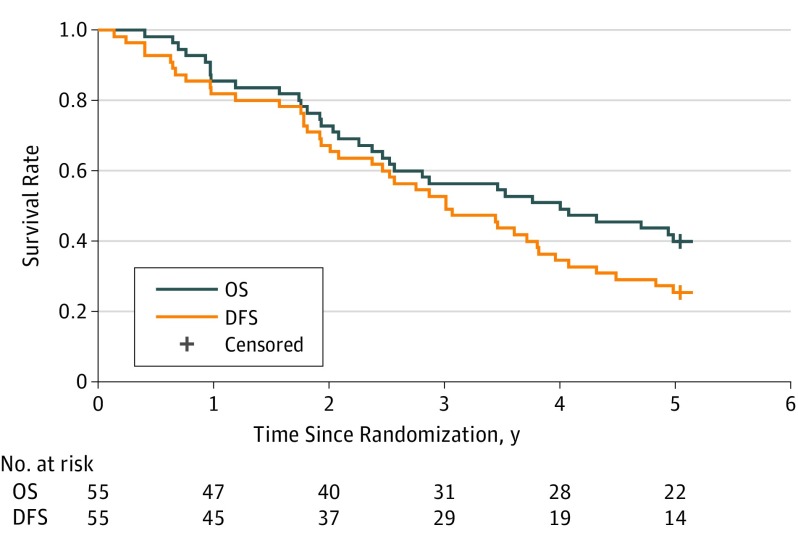

Disease-free survival and overall survival at 5 years was 25.5% (95% CI, 14.9%-37.4%) and 40.0% (95% CI, 27.1%-52.5%), respectively, as shown in Figure 2. Median disease-free survival and overall survival for all patients was 3.0 (95% CI, 2.1-3.8) years and 4.0 (95% CI, 2.5-5.3) years, respectively.

Figure 2. Five-Year Survival.

Overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) from time of randomization.

No grade 5 treatment-related AEs were reported with longer follow-up. Grade 3 and 4 toxic effects were reported in 15 (27.3%) and 2 (3.6%) of the patients, respectively. There were 2 more patients with grade 3 or higher AEs in this report than in the 3-year publication. The majority of these AEs were related to pulmonary or musculoskeletal (eg, rib fracture) categories.

Discussion

Compared with findings in the 3-year report, further follow-up showed additional cancer recurrence, particularly in untreated locations in the chest. Local failure increased with longer follow-up mostly due to involved lobe failures apart from the primary targeted tumor. Blood-borne dissemination, the single largest failure pattern in the initial report, increased to just over 30%.

With longer follow-up, few additional high-grade toxic effects were reported. It appears that the advanced technologies harnessed for this trial avoided the prohibitive late toxic effects that some speculated would appear.6

Our study has limitations. It enrolled only 59 patients and had no control arm for comparison. To our knowledge, it was the first study of its kind such that many centers enrolled with little experience. Technologies used for treatment have evolved and hopefully improved.

The NRG Oncology RTOG 0236 trial demonstrated that technologically intensive treatments, such as SBRT, can be carried out in a cooperative group. While patients continue to experience recurrence and need better therapies, long-term follow-up demonstrates SBRT’s useful performance in at-risk populations and showed that even late toxic effects can be managed by careful application of advanced technology.

References

- 1.Timmerman R, Paulus R, Galvin J, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early stage lung cancer. JAMA. 2010;303(11):1070-1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pan H, Rose BS, Simpson DR, Mell LK, Mundt AJ, Lawson JD. Clinical practice patterns of lung stereotactic body radiation therapy in the United States: a secondary analysis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013;36(3):269-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ClinicalTrials.gov Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy in Treating Patients With Inoperable Stage I or Stage II Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. NCT00087438. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00087438. Accessed March 27, 2018.

- 4.Yang W, Jones R, Lu W, et al. Feasibility of non-coplanar tomotherapy for lung cancer stereotactic body radiation therapy. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2011;10(4):307-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A, et al. CTCAE v3.0: development of a comprehensive grading system for the adverse effects of cancer treatment. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003;13(3):176-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fletcher GH. Hypofractionation: lessons from complications. Radiother Oncol. 1991;20(1):10-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]