Abstract

Retinoic acid is commonly used in culture to differentiate stem cells into neurons and has established neural differentiation functions in vivo in developing and adult organisms. In this issue of Stem Cell Reports, Mishra et al. (2018) broaden its role in stem cell functions, showing that retinoic acid is necessary for stem and progenitor cell proliferation in the adult brain.

Retinoic acid is commonly used in culture to differentiate stem cells into neurons and has established neural differentiation functions in vivo in developing and adult organisms. In this issue of Stem Cell Reports, Mishra et al. (2018) broaden its role in stem cell functions, showing that retinoic acid is necessary for stem and progenitor cell proliferation in the adult brain.

Main Text

It is now well-established that neural stem and progenitor cells (NSPCs) residing in the hippocampus maintain a pool of proliferating stem cells and differentiate to produce new neurons that are implicated in learning and memory functions in adulthood. Many molecular mechanisms that regulate this process (broadly termed “adult neurogenesis”) parallel analogous processes during central nervous system development, though with some twists, as the NSPCs navigate their way through the course of division, differentiation, maturation, and/or death. For example, one fundamentally important process of developmental biology is a carefully orchestrated dynamic balance between cellular proliferation and differentiation. The interactions among signaling factors that maintain dividing progenitors and those that induce fate commitment are critical for proper tissue patterning, growth, and maintenance. Retinoic acid (RA) is one example of a key signal that has historically been recognized as a differentiation-inducing molecule that pushes progenitors away from proliferation (Diez del Corral et al., 2003). In this issue of Stem Cell Reports, however, Mishra and colleagues present new findings that can now place RA on both sides of the scale, showing a role for RA in promoting cellular proliferation in the adult hippocampus (Mishra et al., 2018).

Retinoic acid is a metabolite of vitamin A, which has long been known to be essential for healthy development. One of the earliest manifestations of a vitamin A-deficient diet is impaired vision, and it is from this, and the discovery of vitamin A derivatives in the retina, that retin-oic acid receives its name (Janesick et al., 2015). Many studies commonly use vitamin A-deficient (VAD) diets to disrupt and examine RA signaling. In addition to visual impairments, early VAD animal models displayed many neurological abnormalities, suggesting a vital role for vitamin A and its derivatives in neural development.

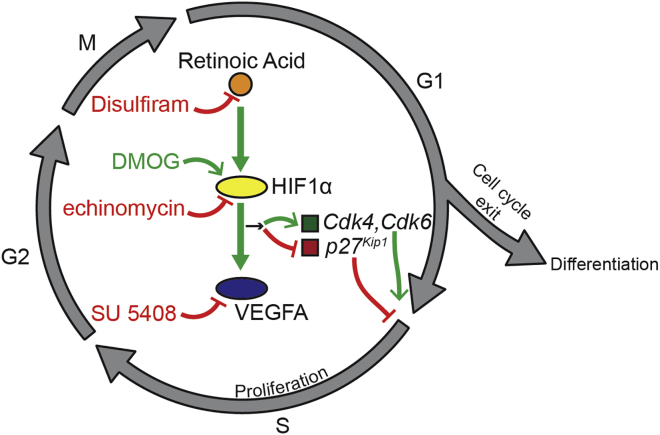

Among other neuronal functions, it is well established that RA is an inducer of neurons from NSPCs in vitro, and over a decade ago, Jacobs and colleagues also demonstrated that in vivo RA is required early in the neuronal differentiation process of the adult hippocampus (Jacobs et al., 2006). The work of Jacobs et al. suggested that RA is necessary for the survival of newborn cells, but not proliferation. Thus it was surprising that in this study, Mishra et al. (2018) found that RA treatment stimulated proliferation of NSPC cultures, while an antagonist of RA receptors blocked this proliferation. Similarly, in an in vivo model using the drug disulfiram (DS) to block RA synthesis and thus lower systemic RA levels, the authors observed a decrease in proliferating NSPCs (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A Retinoic Acid Signaling Pathway to Promote Proliferation

Retinoic acid, acting via HIF1α and VEGF, is necessary for S-phase re-entry of NSPCs. Mishra et al. (2018) utilize several drugs to inhibit (disulfiram, echinomycin, SU 5408; red type) or promote (DMOG; green type) components of this pathway. Altering retinoic acid or HIF1α levels affects positive cell cycle regulators (Cdk4, Cdk6) and a negative regulator (p27Kip1). Red lines, negative regulators. Green lines, positive regulators.

The study then delved deeper into the downstream mechanisms by which RA increases NSPC proliferation and pinpointed the transcriptional regulator HIF1α and its target VEGFA as additional players in this process. VEGFA is synthesized and secreted by hippocampal NSPCs and directly promotes the proliferation of NSPCs (Kirby et al., 2015). Mishra et al. (2018) found that RA treatment increased the levels of both HIF1α and VEGFA in NSPCs, whereas blocking RA correspondingly decreased both targets. Furthermore, drugs that block HIFα or VEGF activity inhibited the positive effect of RA on proliferation, linking these pathway components together (Figure 1). In additional in vivo studies, mice were injected with DMOG, which has been shown to increase HIF1α levels, and this treatment reversed the anti-proliferative effects of DS and by itself significantly increased the number of proliferating NSPCs. Thus the authors concluded that RA is necessary for adult hippocampal NSPC proliferation and that HIF1α and VEGF mediate this regulation.

Another key goal of the study was to examine the extent to which RA effects in NSPCs were cell autonomous. As many studies have relied on a vitamin A-deficient diet to disrupt RA signaling, and thus broadly reduce systemic RA levels, the direct effects of this signaling on NSPCs have not strictly been examined. Thus in addition to systemic disruption of RA with DS, the authors utilized conditional mouse models to specifically impair RA signaling in NSPCs. These experiments corroborated the impacts on cell proliferation, HIF1α, and VEGFA observed in DS-treated mice; however, these results demonstrate that RA signaling functions cell autonomously in NSPCs.

For their final link between RA and proliferation, Mishra et al. (2018) examined whether RA- HIF1α signaling regulates cell cycle kinetics. Disrupting this pathway impaired the G1-S transition of NSPCs during cell cycle progression and also altered gene expression levels of cell cycle regulators (Figure 1). Thus, collectively, this study outlines a novel RA function that works via HIF1α and VEGFA to control cell-cycle re-entry and, in turn, proliferation.

Importantly, Mishra et al. (2018) note that these results do not dismiss a function for RA in promoting neuronal differentiation, and in fact they found that disrupting RA did indeed decrease the numbers of newly born neuroblasts and neurons, consistent with the earlier work of Jacobs et al. (2006). Still, under normal physiological conditions, the balance between proliferation and differentiation must be maintained, and at some point in any single NSPC’s time span a decision is made to continue proliferation or switch to differentiation. At what point does RA signaling favor once choice over the other? An interesting result from Mishra and colleague’s focus on RA signaling specifically in NSPCs was that they found active RA signaling in each NSPC subtype, from stem cell, to intermediate progenitor, to neuroblast (Mishra et al., 2018). However, this active signaling was observed in only a fraction of the cells in each subtype (approximately 8%–18% in the different categories). It could be elucidating to examine whether RA signaling fluctuates across one cell’s time span and if this can dictate a cell’s fate. Additionally, since the neurogenic niche presents such a complex network of different signaling factors, it raises the question of how RA interacts with other mitogenic signals, such as Shh and FGF-2, and whether these interactions differentially refine the effects of RA. This is suggested by the interactions between the RA and FGF pathways during the development and extension of the vertebrate body axis, which results in opposing actions that control and coordinate neural patterning and differentiation (Diez del Corral et al., 2003).

This work has important implications for understanding both endogenous RA signaling and the therapeutics or conditions that alter RA levels, including vitamin A deficiency. The authors particularly point to high RA signaling in the hippocampus, although RA itself is not locally synthesized in the neurogenic niche (Goodman et al., 2012). Rather, they suggest that the meninges are a likely source of RA, which would add to a growing list of long-ranging signals that influence adult neurogenesis but are derived from outside the neurogenic niche, including blood-borne (Villeda et al., 2011, Villeda et al., 2014) and CSF (Silva-Vargas et al., 2016) factors. Additional work examining how meningeal RA synthesis is regulated and the corresponding impact on hippocampal NSPCs will further clarify the now broadened role of RA in the adult brain.

Contributor Information

Kira Irving Mosher, Email: kmosher@berkeley.edu.

David V. Schaffer, Email: schaffer@berkeley.edu.

References

- Diez del Corral R., Olivera-Martinez I., Goriely A., Gale E., Maden M., Storey K. Opposing FGF and retinoid pathways control ventral neural pattern, neuronal differentiation, and segmentation during body axis extension. Neuron. 2003;40:65–79. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00565-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman T., Crandall J.E., Nanescu S.E., Quadro L., Shearer K., Ross A., McCaffery P. Patterning of retinoic acid signaling and cell proliferation in the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2012;22:2171–2183. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs S., Lie D.C., DeCicco K.L., Shi Y., DeLuca L.M., Gage F.H., Evans R.M. Retinoic acid is required early during adult neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:3902–3907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511294103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janesick A., Wu S.C., Blumberg B. Retinoic acid signaling and neuronal differentiation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015;72:1559–1576. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1815-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby E.D., Kuwahara A.A., Messer R.L., Wyss-Coray T. Adult hippocampal neural stem and progenitor cells regulate the neurogenic niche by secreting VEGF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:4128–4133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422448112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S., Kelly K., Rumian N., Siegenthaler J. Retinoic acid is required for neural stem and progenitor cell proliferation. Stem Cell Reports. 2018;10:1705–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.04.024. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Vargas V., Maldonado-Soto A.R., Mizrak D., Codega P., Doetsch F. Age-Dependent Niche Signals from the Choroid Plexus Regulate Adult Neural Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:643–652. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeda S.A., Luo J., Mosher K.I., Zou B., Britschgi M., Bieri G., Stan T.M., Fainberg N., Ding Z., Eggel A. The ageing systemic milieu negatively regulates neurogenesis and cognitive function. Nature. 2011;477:90–94. doi: 10.1038/nature10357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeda S.A., Plambeck K.E., Middeldorp J., Castellano J.M., Mosher K.I., Luo J., Smith L.K., Bieri G., Lin K., Berdnik D. Young blood reverses age-related impairments in cognitive function and synaptic plasticity in mice. Nat. Med. 2014;20:659–663. doi: 10.1038/nm.3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]