Functional insight on the post-translational modifier SUMO and its biochemical pathway in plants has steadily increased over the past decade. In contrast to the low number of core components that catalytically control SUMO attachment to targets, the enzymes that control deconjugation and SUMO maturation seem to have diversified in terms of both gene number and biological function. However, studies on these deSUMOylating proteases have been accompanied by diversity in nomenclature and unclear evolutionary categorization. We provide a state-of-the-art assessment of the evolutionary subclades within the ULP gene family of plant deSUMOylating proteases, and propose a nomenclature for this protease subgroup for consistent annotation of ULP-encoding genes in plant genomes.

The Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier (SUMO) polypeptide is a member of the Ub-fold family, which is collectively defined by a signature β-grasp fold. Like ubiquitin (Ub), SUMO acts in the post-translational modification of proteins, and is important for plant development and adaptive responses to the environment (Castro et al., 2012; Yates et al., 2016). The SUMO conjugation and deconjugation cycles have to be tightly regulated, and numerous SUMO proteases are fundamental for this equilibrium. Several types of deSUMOylating proteases (DSPs) were uncovered in non-plant models, namely ULP/SENPs, DESIs and USPLs, which belong to separate families of cysteine proteases (C48, C97 and C98, respectively) (Hickey et al., 2012; Nayak and Muller, 2014). Presently, the only functionally characterized plant DSPs belong to the Ub-Like Protease (ULP) gene family.

Evolution and nomenclature in plant ULPs

ULPs are cysteine proteases belonging to the C48 family (MEROPS release 12.0; Rawlings et al., 2018). Despite sharing similarities with the catalytic domains of some classes of deubiquitylating proteases, such as Ubiquitin Specific Proteases (UBPs) and Ubiquitin C-terminal Hydrolases (UCHs), they belong to different clans (clan CE for ULPs, and clan CA for UBPs and UCHs). CE and CA proteases share a papain-like fold and, most likely, a common origin (van der Hoorn, 2008; Rawlings et al., 2018). Historically, ULPs have been divided into two large groups (ULP1s and ULP2s), following the identification of two functionally separate paralogs – ScULP1 and ScULP2/Smt4 in yeast (Li and Hochstrasser, 1999, 2000). Later, human ULPs were also differentiated into ULP1s (SENP1, -2, -3 and -5), and ULP2s (SENP6 and -7) (Mukhopadhyay and Dasso, 2007). Plant deSUMOylating proteases belonging to the ULP gene family have mostly been studied in the model plant Arabidopsis. Despite the significant functional advances, difficulties have arisen in establishing definitive gene abundance, phylogeny and nomenclature of this gene family.

Gene abundance

The Arabidopsis genome is assumed to contain eight ULPs (Box 1) (Novatchkova et al., 2012; Castro et al., 2016; Benlloch and Lois, 2018; Garrido et al., 2018). Often, however, only seven have been described because of the failure to incorporate At3g48480 (Novatchkova et al., 2004; Colby et al., 2006; Hoen et al., 2006), as this is a highly truncated form albeit one that retains the protease domain. Also, initial phylogenetic studies incorporated At5g60190 (Novatchkova et al., 2004; Hoen et al., 2006), which was subsequently identified as a deNEDDylating rather than a deSUMOylating protease, and named Deneddylase 1 (DEN1; Box 1) (Colby et al., 2006; Mergner et al., 2015). Initial reports similarly established a massive gene expansion in this gene family (Kurepa et al., 2003; Hoen et al., 2006; Lois, 2010). This has been traced to the presence of at least 97 MULE transposons that contain intact peptidase C48 domains, and are likely to have expanded via ancient transduplication events (Hoen et al., 2006). Though these amplified genomic loci may encode polypeptides that possess SUMO protease activity, they are phylogenetically more distant than the deNEDDylating protease DEN1 when compared to ULPs, and display low or undetectable expression, which suggests they are unlikely to act towards SUMO (Hoen et al., 2006). Hoen and co-workers (2006) have named these Kaonashi (KI) elements, and here we propose a definitive nomenclature as Kaonashi ULP Like Proteases (KIUs) (Box 1).

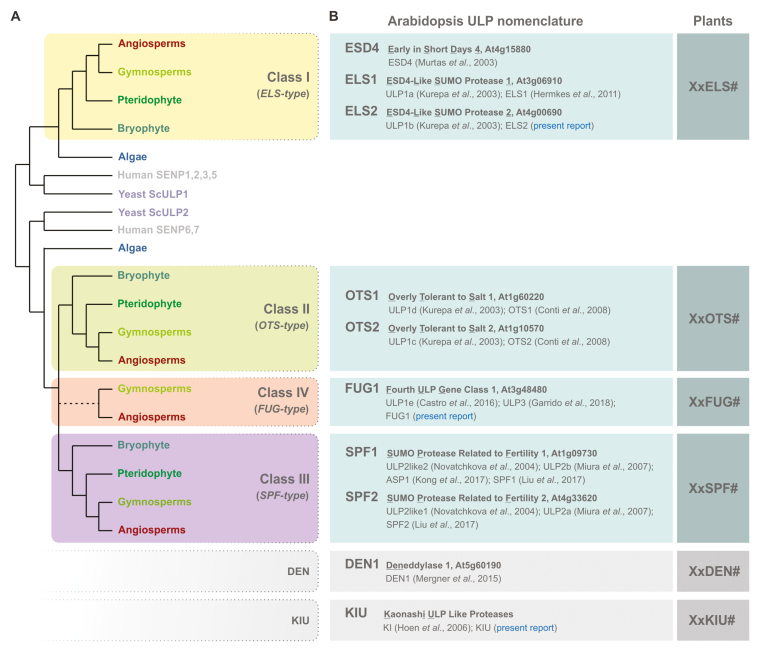

Box 1. Plant ULP evolution and nomenclature

A schematic tree, depicting currently accepted phylogenetic relationships between organisms, summarizes the evolutionary path of the plant ULP gene family of deSUMOylating proteases. Plant ULPs have a polyphyletic origin than can be traced to green algae and ultimately to examples in other eukaryotes, including ScULP1 and ScULP2. ULP1s form a homogenous class (Class I, ELS-type), while ULP2s branch out into Class II (OTS-type) and Class III (SPF-type) proteases during early plant evolution. Class IV (FUG-type) consistently appears in flowering plant genomes and seems absent from early plant taxa, but its origin remains elusive (Castro et al., 2018).

Existing nomenclature for all Arabidopsis ULPs. We propose a nomenclature that reflects biological function and assumed phylogenetic relationships. It incorporates new gene names for two Arabidopsis ULPs (highlighted in blue). In future annotation of plant genomes, plant ULPs may be spelled with a prefix of the species, followed by increasing numbering. For example, tomato Class II ULPs may be named SlOTS1, SlOTS2, and so on. References in main text; see also Miura et al., 2007.

Gene phylogeny

The eight canonical Arabidopsis ULPs have consistently been categorized in light of their strong amino acid sequence conservation to yeast ULP1 or ULP2 (Kurepa et al., 2003; Novatchkova et al., 2004; Mukhopadhyay and Dasso, 2007; Lois, 2010), though they can be resolved into additional phylogenetic subgroups (Colby et al., 2006; Novatchkova et al., 2012) (Box 1). Insight based on more extensive comparative genomics data suggests that At4g15880/At3g06910/At4g00690 form a homogenous class of ULP1s (homologous to yeast ScULP1). In contrast, Arabidopsis homologs of ScULP2 can be divided into three classes, containing At4g33620/At1g09730, At1g10570/At1g60220 and At3g48480 (Novatchkova et al., 2012; Castro et al., 2018). Existence of four classes is also supported by protein topological data, namely protein size and the location of the ULP domain (Benlloch and Lois, 2018; Castro et al., 2018). Here, we propose a definitive classification for the four plant ULP classes (Classes I–IV) based on the Arabidopsis ULPs (Box 1).

Gene nomenclature

The community has been struggling to define a coherent naming of Arabidopsis ULPs. Initially they were named after assumed phylogenetic relatedness to ULP1 or ULP2 proteins. Erroneously, this led to the naming of At1g10570, At1g60220 and At3g48480 as ULP1c, ULP1d and ULP1e, respectively (Kurepa et al., 2003; Lois, 2010; Castro et al., 2016), even though they are phylogenetically related to ULP2s. Functional studies in Arabidopsis generated an increasing number of names that disregarded molecular function in favor of biological function, resulting in several parallel nomenclatures. Most ULP genes have between two and as many as four names for a single member. It is important to clarify this matter to create a consensual nomenclature based on biological function, while at the same time respecting known phylogenetic data. The proposed nomenclature is detailed in Box 1.

ULP function

It is well established in non-plant models that ULPs are regulated at various levels, including enzymatic activity, SUMO isoform discrimination, subcellular localization and expression patterns (Hickey et al., 2012; Nayak and Muller, 2014; Kunz et al., 2018). A series of clues point towards similarly complex functionalities for plant ULPs. Characterization of loss-of-function Arabidopsis ULP mutants has implicated the different ULP classes in non-redundant functions during plant development. The esd4 mutant has a pleiotropic phenotype accompanied by early flowering, partially due to SA accumulation (Murtas et al., 2003; Villajuana-Bonequi et al., 2014), while loss-of-function of its closest paralog ELS1 does not display such a drastic phenotype (Hermkes et al., 2011). OTS mutants assume a mild developmental phenotype (smaller and early-flowering plants), and are also implicated in abiotic and biotic stress resistance (Conti et al., 2008; Bailey et al., 2016; Castro et al., 2016). In contrast, SPF-class mutants are late flowering, and display an altered growth pattern and embryo development defects (Kong et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017; Castro et al., 2018). The fourth class of ULPs, represented in Arabidopsis by FUG1, is yet to be functionally addressed. Future studies may bring to light additional deSUMOylating protease gene families other than ULPs, adding complexity to the SUMO pathway.

As previously established for non-plant ULPs, different subcellular targeting is an important aspect of ULP molecular function (Hickey et al., 2012; Nayak and Muller, 2014; Kunz et al., 2018). In Arabidopsis, ESD4 interacts with the nuclear pore component NUA, which concentrates its location at the inner nuclear side of the nuclear pore (Xu et al., 2007). In contrast, ELS1 resides in the cytoplasm, which supports low functional redundancy between Class I proteases in Arabidopsis (Hermkes et al., 2011). OTS1, OTS2, SPF1 and SPF2 are nuclear proteins (Conti et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2017; Castro et al., 2018). With the possible exception of the functionally uncharacterized genes ELS2 and FUG1, Arabidopsis ULPs are widely expressed. In classes I and II, there is one ULP that is more expressed than the remaining class members (ESD4 and OTS1, respectively). OTS1 and OTS2 seem to display similar expression patterns but differences in expression amplitude, while SPF1 and SPF2 show differential expression patterns, collectively explaining the existence of unequal functional redundancy in these gene pairs (Castro et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017; Castro et al., 2018).

Further research on plant deSUMOylating proteases

Our understanding of the functions of deSUMOylation, reviewed more extensively by Benlloch and Lois (2018), is at present very limited. Foremost among future research efforts is determining whether deSUMOylating proteases in general, and ULPs in particular, display a preferential capacity to act as endopeptidases (involved in maturation of preSUMO peptides) or as isopeptidases (removal of SUMOs from SUMO conjugates). Also of significance is the establishment of affinity towards the different SUMO isoforms present in plant genomes, and whether they display capacity to process polySUMO chains. Crystal structure and docking studies of catalytic domains are also needed to complement our analysis of proteolytic activity. The over-representation of ULP gene members in plant genomes in comparison with SUMO conjugation components (Augustine et al., 2016; Castro et al., 2018; Garrido et al., 2018), suggests that ULPs are likely to function, to some extent, as sources of specificity within the SUMO pathway. Proteomics strategies to identify large numbers of SUMO conjugates are progressively being introduced in Arabidopsis SUMO research (Budhiraja et al., 2009; Miller et al., 2010; Lopez-Torrejon et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2013; Rytz et al., 2018). Application of these strategies in ULP mutant backgrounds should help us define the target specificity of these proteases.

As we move away from Arabidopsis to non-model plants, it is important to have a clear vision of ULP function and target specificity, but also of gene abundance and the evolutionary pathway of this gene family. Sound and precise nomenclature should provide a beneficial contribution.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided to AB [Austrian Research Fund FWF (Grant P 31114)], LML [MINECO BIO2017-89874-R], HA [NORTE 2020 through FEDER (NORTE-01-0145-FEDER-000007), and FEDER /COMPETE and FCT (UID/BIA/50027/2013; POCI-01-0145-FEDER-006821)].

References

- Augustine RC, York SL, Rytz TC, Vierstra RD. 2016. Defining the SUMO system in maize: SUMOylation is up-regulated during endosperm development and rapidly induced by stress. Plant Physiology 171, 2191–2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey M, Srivastava A, Conti L, et al. . 2016. Stability of small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) proteases OVERLY TOLERANT TO SALT1 and -2 modulates salicylic acid signalling and SUMO1/2 conjugation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Experimental Botany 67, 353–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benlloch R, Lois LM. 2018. Sumoylation in plants: mechanistic insights and its role in drought stress. Journal of Experimental Botany 69, 4539–4554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budhiraja R, Hermkes R, Müller S, Schmidt J, Colby T, Panigrahi K, Coupland G, Bachmair A. 2009. Substrates related to chromatin and to RNA-dependent processes are modified by Arabidopsis SUMO isoforms that differ in a conserved residue with influence on desumoylation. Plant Physiology 149, 1529–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro PH, Couto D, Freitas S, et al. . 2016. SUMO proteases ULP1c and ULP1d are required for development and osmotic stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Molecular Biology 92, 143–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro PH, Santos MA, Freitas S, et al. . 2018. Arabidopsis thaliana SPF1 and SPF2 are nuclear-located ULP2-like SUMO proteases that act downstream of SIZ1 in plant development. Journal of Experimental Botany 69, 4633–4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro PH, Tavares RM, Bejarano ER, Azevedo H. 2012. SUMO, a heavyweight player in plant abiotic stress responses. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 69, 3269–3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby T, Matthäi A, Boeckelmann A, Stuible HP. 2006. SUMO-conjugating and SUMO-deconjugating enzymes from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 142, 318–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti L, Price G, O’Donnell E, Schwessinger B, Dominy P, Sadanandom A. 2008. Small ubiquitin-like modifier proteases OVERLY TOLERANT TO SALT1 and -2 regulate salt stress responses in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 20, 2894–2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido E, Srivastava AK, Sadanandom A. 2018. Exploiting protein modification systems to boost crop productivity: SUMO proteases in focus. Journal of Experimental Botany 69, 4625–4632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermkes R, Fu YF, Nürrenberg K, Budhiraja R, Schmelzer E, Elrouby N, Dohmen RJ, Bachmair A, Coupland G. 2011. Distinct roles for Arabidopsis SUMO protease ESD4 and its closest homolog ELS1. Planta 233, 63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey CM, Wilson NR, Hochstrasser M. 2012. Function and regulation of SUMO proteases. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 13, 755–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoen DR, Park KC, Elrouby N, Yu Z, Mohabir N, Cowan RK, Bureau TE. 2006. Transposon-mediated expansion and diversification of a family of ULP-like genes. Molecular Biology and Evolution 23, 1254–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong X, Luo X, Qu GP, Liu P, Jin JB. 2017. Arabidopsis SUMO protease ASP1 positively regulates flowering time partially through regulating FLC stability. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 59, 15–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz K, Piller T, Muller S. 2018. SUMO-specific proteases and isopeptidases of the SENP family at a glance. Journal of Cell Science 131, doi: 10.1242/jcs.211904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurepa J, Walker JM, Smalle J, Gosink MM, Davis SJ, Durham TL, Sung DY, Vierstra RD. 2003. The small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) protein modification system in Arabidopsis. Accumulation of SUMO1 and -2 conjugates is increased by stress. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 278, 6862–6872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SJ, Hochstrasser M. 1999. A new protease required for cell-cycle progression in yeast. Nature 398, 246–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SJ, Hochstrasser M. 2000. The yeast ULP2 (SMT4) gene encodes a novel protease specific for the ubiquitin-like Smt3 protein. Molecular and Cellular Biology 20, 2367–2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Jiang Y, Zhang X, et al. . 2017. Two SUMO Proteases SUMO PROTEASE RELATED TO FERTILITY1 and 2 Are Required for Fertility in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 175, 1703–1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois LM. 2010. Diversity of the SUMOylation machinery in plants. Biochemical Society Transactions 38, 60–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Torrejón G, Guerra D, Catalá R, Salinas J, del Pozo JC. 2013. Identification of SUMO targets by a novel proteomic approach in plants(F). Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 55, 96–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergner J, Heinzlmeir S, Kuster B, Schwechheimer C. 2015. DENEDDYLASE1 deconjugates NEDD8 from non-cullin protein substrates in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Cell 27, 741–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MJ, Barrett-Wilt GA, Hua Z, Vierstra RD. 2010. Proteomic analyses identify a diverse array of nuclear processes affected by small ubiquitin-like modifier conjugation in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 107, 16512–16517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MJ, Scalf M, Rytz TC, Hubler SL, Smith LM, Vierstra RD. 2013. Quantitative proteomics reveals factors regulating RNA biology as dynamic targets of stress-induced SUMOylation in Arabidopsis. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 12, 449–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K, Jin JB, Hasegawa PM. 2007. Sumoylation, a post-translational regulatory process in plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 10, 495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay D, Dasso M. 2007. Modification in reverse: the SUMO proteases. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 32, 286–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtas G, Reeves PH, Fu YF, Bancroft I, Dean C, Coupland G. 2003. A nuclear protease required for flowering-time regulation in Arabidopsis reduces the abundance of SMALL UBIQUITIN-RELATED MODIFIER conjugates. The Plant Cell 15, 2308–2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak A, Müller S. 2014. SUMO-specific proteases/isopeptidases: SENPs and beyond. Genome Biology 15, 422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novatchkova M, Budhiraja R, Coupland G, Eisenhaber F, Bachmair A. 2004. SUMO conjugation in plants. Planta 220, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novatchkova M, Tomanov K, Hofmann K, Stuible HP, Bachmair A. 2012. Update on sumoylation: defining core components of the plant SUMO conjugation system by phylogenetic comparison. New Phytologist 195, 23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Thomas PD, Huang X, Bateman A, Finn RD. 2018. The MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors in 2017 and a comparison with peptidases in the PANTHER database. Nucleic Acids Research 46, D624–D632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytz TC, Miller MJ, McLoughlin F, Augustine RC, Marshall RS, Juan YT, Charng YY, Scalf M, Smith LM, Vierstra RD. 2018. SUMOylome profiling reveals a diverse array of nuclear targets modified by the SUMO Ligase SIZ1 during heat stress. The Plant Cell 30, 1077–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hoorn RA. 2008. Plant proteases: from phenotypes to molecular mechanisms. Annual Review of Plant Biology 59, 191–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villajuana-Bonequi M, Elrouby N, Nordström K, Griebel T, Bachmair A, Coupland G. 2014. Elevated salicylic acid levels conferred by increased expression of ISOCHORISMATE SYNTHASE 1 contribute to hyperaccumulation of SUMO1 conjugates in the Arabidopsis mutant early in short days 4. The Plant Journal 79, 206–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XM, Rose A, Muthuswamy S, Jeong SY, Venkatakrishnan S, Zhao Q, Meier I. 2007. NUCLEAR PORE ANCHOR, the Arabidopsis homolog of Tpr/Mlp1/Mlp2/megator, is involved in mRNA export and SUMO homeostasis and affects diverse aspects of plant development. The Plant Cell 19, 1537–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates G, Srivastava AK, Sadanandom A. 2016. SUMO proteases: uncovering the roles of deSUMOylation in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 67, 2541–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]