Abstract

Pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCN) include different types of cysts with various biological behavior. The most prevalent PCN are intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN), mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN), and serous cystic neoplasm (SCN). Management of PCN should focus on the prevention of malignant progression, while avoiding unnecessary morbidity of surgery. This requires specialized centers with dedicated multidisciplinary PCN teams. The malignant potential of PCN varies enormously between the various types of PCN. A combination of computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, and endoscopic ultrasound with or without fine needle aspiration is typically needed before a reliable diagnosis can be made. Several guidelines discuss the management of PCN; however, most of these are non-evidence-based without clear consensus on the optimal treatment and follow-up strategy. The 2018 European guidelines on PCN are the first evidence-based guidelines to include IPMN, MCN, SCN, and all other PCN. This guideline advises a more conservative approach to side-branch IPMN and MCN smaller than 40 mm and more often a surgical approach in IPMN with a main duct dilatation beyond 5 mm. The goal of this review is to summarize the different types and management of the most common PCN based on the current literature and guidelines.

Keywords: Pancreatectomy, Pancreatic cystic neoplasms, Mucinous cyst, Serous cyst

Introduction

Over the past decades our knowledge about pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCN) has evolved greatly. PCN differ in their clinical presentation, morphology, and risks of malignancy. Some are benign (e.g. serous cystic neoplasms (SCN)), without a risk of malignancy, while others carry a small or larger risk of malignancy (e.g. intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) and mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCN)). Knowledge of these different characteristics and morphological variations is important to reach the correct PCN diagnosis, which determines the management and follow-up strategy.

The first international guideline for the management of IPMN was published by a group of experts of the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP) in 2006 and was followed by two updates in 2012 and 2017 [1,2,3]. The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) institute evidence-based guidelines were published in 2015 but do not address all PCN individually [4]. The European Study Group on Cystic Tumors of the Pancreas published an experts consensus statement in 2013 [5] which was followed by the recent evidence-based guideline, addressing all individual PCN, in contrast to the other guidelines [6]. The current guidelines show many similarities but also differences in surveillance and surgical strategy for IPMN and MCN. This review aims to provide the reader with an overview of the current literature and (evidence-based) guidelines.

Classification

The most clinically relevant classification of PCN is based on their cystic content, i.e. mucinous or non-mucinous (table 1). The non-mucinous PCN (e.g. SCN, simple cyst) are benign whereas the mucinous PCN (e.g. IPMN, MCN) have a certain malignant potential. In main-duct IPMN (MD-IPMN), the risk of malignancy in surgical series is 33-60% [3]. MCN is associated with a 10-15% risk of malignancy in surgical series [7]. The solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPN) are less common, with a risk of malignancy ranging from 10 to 16% [8,9]. Further rare PCN, including cystic acinar cell adenoma and serous cystadenocarcinoma, will not be discussed here.

Table 1.

Pancreatic cystic neoplasms

Epidemiology

Because of the increased use of cross-sectional imaging and the increased awareness, PCN are increasingly being diagnosed, often as an incidental finding [10]. The exact prevalence of the different PCN is not known. Studies which assessed the prevalence rate of asymptomatic PCN reported a prevalence of 2.2-2.6% with computed tomography (CT) [10,11,12,13] and a prevalence of 14-45% with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [13,14,15]. This risk increases with age [10,11,12].

The various types of PCN show a different age and sex distribution. SCN, accounting for 1-2% of all exocrine pancreatic neoplasms, are often diagnosed at the age of 50-70 years, and the incidence is higher in women (70%) than in men [16]. IPMN is often diagnosed around the age of 60 years, with equal incidence in women and men. MCN, accounting for 2-5% of all exocrine pancreas neoplasms, are mostly diagnosed at the age of 40-60 years and almost exclusively in women (95%) [17]. SPN are often diagnosed in young patients (20-30 years), with a higher incidence among women.

Radiology

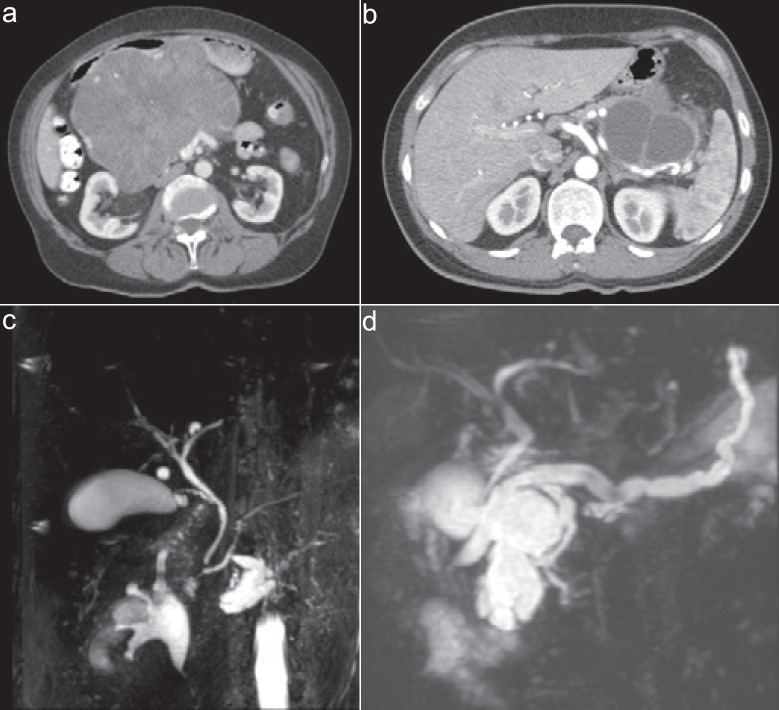

Although different imaging modalities are available, distinguishing PCN subtypes may prove difficult [18,19,20] (fig. 1). The first step when assessing PCN is to perform an MRI/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, which differentiates approximately 40-95% of PCN compared with 40-81% for CT [6]. In order to exclude high-risk features or when malignancy is suspected, without a definitive mass on CT, endoscopic ultrasound is performed, differentiating 48-94% of PCN when performed in expert hands [6].

Fig. 1.

Examples of the most common subtypes of pancreatic cystic neoplasms. a Serous cystic neoplasm, b mucinous cystic neoplasm, c side-branch intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN), d main-duct IPMN.

SCN are often localized in the body or tail of the pancreas (50-75%) [16]. Macroscopically, SCN are single round lesions (1-25 cm) made of multiple small cysts (0.01-0.5 cm) ordered in a so-called honeycomb pattern. Often, these small cysts are arranged around a centrally located dense fibronodular core (central stellate scar). There is no connection between the cysts and the pancreatic duct.

The majority of IPMN is located in the head of the pancreas [2,21]. A single cystic mass as well as segmental involvement or involvement of the entire pancreatic duct can be present. There are three subtypes of IPMN based on the localization in the pancreas: Side-branch IPMN is localized in the side branches with connection to the pancreatic duct. MD-IPMN is localized in the pancreatic duct, and mixed-type IPMN is localized in both the main duct and the side branches. Side-branch IPMN has a lower risk (2-25%) of malignancy, especially when compared to the 33-60% risk of MD-IPMN and mixed-type IPMN in surgical series [2]. The presence of a solid component, enhancing mural nodule, increasing dilation of the pancreatic duct beyond 5 mm, and larger cyst diameter are associated with increased risk of malignancy [6].

MCN is suggested when a unilocular or macrocystic cyst (2-35 cm) with or without nodular calcifications is seen in the body/tail of the pancreas. The cystic wall is thick, with a cellular ‘ovarian' stroma. There is no connection between the cyst and the pancreatic duct. Several characteristics, such as cyst size and mural nodules, are associated with the grade of malignancy [17,22,23]. The recent European guideline is the first to highlight the low risk of malignancy when MCN are smaller than 40 mm [6].

Biomarkers in Blood and Cyst Fluid

Currently, no protein biomarkers have been identified in peripheral blood to differentiate subtypes of PCN or to identify malignant or dysplastic cysts. Serum carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 could be of value in IPMN patients, whereas malignancy or invasive IPMN could be suggested when serum CA 19-9 levels exceed ≥37 U/ml [24,25].

Cystic fluid analysis can occasionally be used to further differentiate between the various PCN. Several biochemical analyses are available, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CA 19-9, amylase and lipase, viscosity, mucin stain, and cytology [26]. Even several cyst fluid DNA markers, such as GNAS and KRAS, have shown to be specific and sensitive for diagnosing IPMN [27,28].

In IPMN and MCN, the cystic fluid is typically quite thick with cytology confirming the presence of mucinous cells. CEA levels may be used to distinguish between mucinous and non-mucinous cysts [29]. A CEA level of >192 µg/l has been shown to be accurate with a sensitivity and specificity of 52-78% and 63-91%, respectively. [30] In case of IPMN, the amylase level will be elevated (>250 U/l) because of the connection of the cyst with the pancreatic duct. In MCN, the amylase level is usually normal, but a high level will not exclude an MCN.

The cyst fluid CA 19-9 level is not sensitive for discriminating benign from malignant PCN [31]. In SCN, the consistence of cystic fluid is thin because it is serous and does not contain mucin. Amylase and CEA levels (<5) are often low.

Operative Management

Some guidelines recommend surgery in all surgically fit patients with MD-IPMN while others recommend surgery if the pancreatic duct is dilated ≥10 mm [6]. Some guidelines recommend total pancreatectomy in young patients who can handle the complexities of diabetes and exocrine insufficiency, while the other guidelines do not mention total pancreatectomy. A recent international survey assessed the preferred surgical treatment strategy (e.g. partial or total pancreatectomy) of 97 experts in IPMN and found a lack of consensus [32]. In case of MD- and mixed-type IPMN with >5 mm dilatation in the entire pancreas, 41% advised surveillance every 3-6 months, whereas 59% advised operative intervention (31% partial pancreatectomy, 46% total pancreatectomy) [32].

Regarding the decision making whether to operate or follow up patients, several factors need to be considered: the overall health status, comorbidities, and the life expectancy of the patient. With the use of cross-sectional imaging and additional biomarkers, a group of patients can be identified who have no risk of malignancy (e.g. SCN). These patients essentially require no surveillance or routine follow-up [33,34]. SCN are often detected as an incidental finding with imaging for other reasons. These cysts are asymptomatic but could increase in size and cause obstruction (biliary, gastric outlet). For asymptomatic patients with radiological diagnosis of SCN, follow-up is not required. When SCN increase in size and become symptomatic, operative intervention is advised [35].

In MCN, cyst size is associated with the risk of malignancy [22,23]. The European guideline is the first to advise a conservative approach when the cyst size is <40 mm. An operation is advised, regardless of MCN size, when a mural nodule is present or when the patient experiences symptoms [30]. Since most MCN are located in the tail of the pancreas, a distal pancreatectomy with or without splenectomy is most often sufficient. After a complete resection there is an almost 100% cure rate [36].

The treatment of choice for SPN is complete resection, which is associated with long-term survival [37,38]. Different procedures are performed and are subsequently dependent on the tumor location.

In IPMN, the risk of malignancy is associated with cyst size and the degree of pancreatic duct dilation in case of MD- or mixed-type IPMN [1,6]. According to the European guidelines, there is an absolute indication for operation when jaundice, an enhancing mural nodule of >5 mm, and pancreatic duct dilation of >10 mm are present. If there is a pancreatic dilation of 5-9.9 mm, there is a relative indication for surgery in IPMN. The type of operation depends on the localization and the multifocal aspect of the tumor. If there is a suspected cancer in the head of the pancreas in a patient with IPMN, even with pancreatic duct dilation in the entire pancreas, a pancreatoduodenectomy is advised, as the cancer will determine the patient's prognosis. In young and fit patients with MD-IPMN in the entire pancreas but no cancer present, a total pancreatectomy should be considered since lifelong follow-up will be required given the risk of recurrence after partial pancreatectomy [6]. The indications for surgery are shown in figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Indications for surgery. Reproduced from [6] with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. EUS = Endoscopic ultrasound; IPMN = intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm.

Follow-up

Because of the high risk of malignancy and recurrence after IPMN surgery, especially for MD-/mixed-type IPMN, a lifelong follow-up is advised in patients who are fit to undergo operative intervention. In case of low-grade dysplasia, the IPMN recurrence rate is 5-10%, while this risk amounts to >50% in case of high-grade dysplasia [30]. Once patients develop IPMN-associated cancer, without lymph node metastases, the outcome is better than for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [39].

European Guidelines

There is no consensus between the three international guidelines on IPMN management (table 2) [3,4,30]. The 2015 AGA guidelines are the most conservative and advise surgery only if a pancreatic duct dilation of ≥5 mm and a solid component is present or if the cytology is positive for malignancy. Furthermore, total pancreatectomy is not mentioned as an option in the AGA guidelines. The European guideline is the most current as well as the only evidence-based guideline that discusses the management of all types of PCN [30].

Table 2.

Recent guidelines for the management of pancreatic cystic neoplasms

| Guidelines | Year | Evidence-based | Type of PCN | Absolute indications for surgery | Relative indication for surgery | Total pancreatectomy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European guideline [6] | 2018 | yes | IPMN | • jaundice | • Growth rate≥ 5 mm/year | • pancreatic duct dilation + mural nodule |

| MCN | • positive cytology (malignancy/HGD) | • increased serum CA 19-9 (>37 U/ml) | ||||

| SCN | • pancreatic duct dilatation 5–9.9 mm | • to consider in patients with an increased risk for malignancy | ||||

| PNEN | • solid mass | • IPMN and MCN≥ 40 mm | ||||

| SPN | • pancreatic duct≥ 10 mm | • new-onset diabetes mellitus | ||||

| rare cysts | • acute pancreatitis (caused by IPMN) | |||||

| • enhancing mural nodules≥ 5 mm | • enhancing mural nodule < 5 mm | |||||

| International Association of Pancreatology [3] | 2017 | no | IPMN | • jaundice | • pancreatitis | • selectively in younger patients |

| SCN | • enhancing mural nodule > 5 mm | • growth rate > 5 mm/2 years | ||||

| • increased serum level of CA 19-9 | • threshold should perhaps be lowered in patients with a strong family history of PDAC | |||||

| • pancreatic duct dilation > 10 mm | • pancreatic duct dilation 5–9 mm | |||||

| • cyst diameter > 30 mm | ||||||

| • enhancing mural nodule < 5 mm | ||||||

| • thickened/enhancing cyst walls | ||||||

| • abrupt change in calibre of pancreatic duct with distal pancreatic atrophy | ||||||

| • lymphadenopathy | ||||||

| American Gastroenterological Association [4] | 2015 | yes | asymptomatic | • pancreatic duct≥ 5 mm + solid component or cytology positive for malignancy | • not mentioned | • not mentioned |

| IPMN and | ||||||

| MCN | ||||||

IPMN = Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm; MCN = mucinous cystic neoplasm; SCN = serous cystic neoplasm; PNEN = cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour; SPN = solid pseudopapillary neoplasm; HGD = high-grade dysplasia; PDAC = pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Conclusions

The risk of malignancy is associated with the type of PCN, and the best approach to further differentiate the type of PCN is combined evaluation of clinical, radiological and endoscopic ultrasonography findings. The risk of malignancy needs to be weighed against the operative intervention risks by experienced PCN teams in high-volume pancreatic surgery centers. Future studies are needed to better determine the indication for partial and total pancreatectomy in IPMN and to decide on the optimal follow-up schedule for patients with IPMN and MCN who did not undergo surgery.

Disclosure Statement

MGB received a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society (grant number UVA2013-5842)) for studies on pancreatic cancer. LS received a grant from Zealand Pharma A/S for a study on post-pancreatectomy diabetes management.

References

- 1.Tanaka M, et al.;, International Association of Pancreatology International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2006;6:17–32. doi: 10.1159/000090023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka M, et al.;, International Association of Pancreatology International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012;12:183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka M, et al. Revisions of international consensus Fukuoka guidelines for the management of IPMN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2017;17:738–753. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vege SS, Ziring B, Jain R, Moayyedi P;, Clinical Guidelines Committee; American Gastroenterology Association American gastroenterological association institute guideline on the diagnosis and management of asymptomatic neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:819–822. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Chiaro M, et al.;, European Study Group on Cystic Tumours of the Pancreas European experts consensus statement on cystic tumours of the pancreas. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:703–711. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Study., Group on Cystic Tumours of the Pancreas European evidence-based guidelines on pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Gut. 2018;67:789–804. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crippa S, et al. Mucin-producing neoplasms of the pancreas: an analysis of distinguishing clinical and epidemiologic characteristics. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim MJ, et al. Surgical treatment of solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas and risk factors for malignancy. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1266–1271. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang WB, et al. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas with liver metastasis: clinical features and management. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:1572–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Jong K, et al. High prevalence of pancreatic cysts detected by screening magnetic resonance imaging examinations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:806–811. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang YR, et al. Incidental pancreatic cystic neoplasms in an asymptomatic healthy population of 21,745 individuals: large-scale, single-center cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e5535. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laffan TA, et al. Prevalence of unsuspected pancreatic cysts on MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:802–807. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ip IK, et al. Focal cystic pancreatic lesions: assessing variation in radiologists' management recommendations. Radiology. 2011;259:136–141. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee KS, et al. Prevalence of incidental pancreatic cysts in the adult population on MR imaging. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2079–2084. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Girometti R, et al. Incidental pancreatic cysts on 3D turbo spin echo magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography: prevalence and relation with clinical and imaging features. Abdom Imaging. 2011;36:196–205. doi: 10.1007/s00261-010-9618-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Capella C, et al. Serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. In: Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2000. pp. 231–250. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nilsson LN, et al. Nature and management of pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN): a systematic review of the literature. Pancreatology. 2016;16:1028–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nougaret S, et al. Incidental pancreatic cysts: natural history and diagnostic accuracy of a limited serial pancreatic cyst MRI protocol. Eur Radiol. 2014;24:1020–1029. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahani DV, et al. Cystic pancreatic lesions: a simple imaging-based classification system for guiding management. Radiographics. 2005;25:1471–1484. doi: 10.1148/rg.256045161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaheer A, et al. Incidentally detected cystic lesions of the pancreas on CT: review of literature and management suggestions. Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:331–341. doi: 10.1007/s00261-012-9898-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furuta K, et al. Differences between solid and duct-ectatic types of pancreatic ductal carcinomas. Cancer. 1992;69:1327–1333. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920315)69:6<1327::aid-cncr2820690605>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keane MG, et al. Risk of malignancy in resected pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasms. Br J Surg. 2018;105:439–446. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Postlewait LM, et al. Association of preoperative risk factors with malignancy in pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasms: a multicenter study. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:19–25. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.3598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim , JR, et al. Clinical implication of serum carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 for the prediction of malignancy in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of pancreas. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:699–707. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang W, et al. Serum carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 for prediction of malignancy and invasiveness in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: a meta-analysis. Biomed Rep. 2015;3:43–50. doi: 10.3892/br.2014.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linder JD, et al. Cyst fluid analysis obtained by EUS-guided FNA in the evaluation of discrete cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: a prospective single-center experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:697–702. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singhi AD, et al. Preoperative GNAS and KRAS testing in the diagnosis of pancreatic mucinous cysts. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:4381–4389. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singhi AD, et al. Preoperative next-generation sequencing of pancreatic cyst fluid is highly accurate in cyst classification and detection of advanced neoplasia. Gut. 2017 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313586. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soyer OM, et al. Role of biochemistry and cytological analysis of cyst fluid for the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cysts: a retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e5513. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.European Study., Group on Cystic Tumours of the Pancreas European evidence-based guidelines on pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Gut. 2018;67:789–804. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao S, et al. Serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 in differential diagnosis of benign and malignant pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0166406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scholten L, et al. Surgical management of main duct IPMN and mixed type IPMN: an international survey and case-vignette study among experts. Pancreatology. 2017;17((suppl)):S87. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reid MD, et al. Serous neoplasms of the pancreas: a clinicopathologic analysis of 193 cases and literature review with new insights on macrocystic and solid variants and critical reappraisal of so-called ‘serous cystadenocarcinoma'. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:1597–1610. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strobel O, et al. Risk of malignancy in serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Digestion. 2003;68:24–33. doi: 10.1159/000073222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pelaez-Luna MC, et al. Serous cystadenomas follow a benign and asymptomatic course and do not present a significant size change during follow-up. Rev Invest Clin. 2015;67:344–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zamboni G, et al. Mucinous cystic tumors of the pancreas: clinicopathological features, prognosis, and relationship to other mucinous cystic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:410–422. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199904000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cai H, et al. Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas: clinical and pathological features of 33 cases. Surg Today. 2013;43:148–154. doi: 10.1007/s00595-012-0260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reddy S, et al. Surgical management of solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas (Franz or Hamoudi tumors): a large single-institutional series. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:950–957. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.01.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salvia R, et al. Main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: clinical predictors of malignancy and long-term survival following resection. Ann Surg. 2004;239:678–685. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000124386.54496.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]