Abstract

Temple syndrome (TS14) is a relatively recently discovered imprinting disorder caused by abnormal expression of genes at the locus 14q32. The underlying cause of this syndrome is maternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 14 (UPD(14)mat). Trisomy of chromosome 14 is one of the autosomal trisomies; in humans, it is only compatible with live birth in mosaic form. Although UPD(14)mat and mosaic trisomy 14 can arise from the same cellular mechanism, a combination of both has been currently reported only in 8 live-born cases. Hereby, we describe a patient in whom only UPD(14)mat-associated TS14 was primarily diagnosed. Due to the patient's atypical features (for TS14), additional analyses were performed and low-percent mosaic trisomy 14 was detected. It can be expected that the described combination of 2 etiologically related conditions is actually more prevalent. Additional chromosomal and molecular investigations are indicated for every patient with UPD(14)mat-associated TS14 with atypical clinical presentation.

Keywords: Imprinting disorders, Maternal uniparental disomy 14, Mosaicism, Temple syndrome, Trisomy 14

Imprinting disorders are a small group of rare congenital diseases caused by changes in expression of imprinted genes, affecting mainly growth, development, and metabolism. Temple syndrome (TS14) is 1 of 12 known imprinting disorders, first described by Temple et al. [1991] in a young male with a balanced Robertsonian translocation (13;14) and maternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 14 (UPD(14)mat). TS14 is characterized by prenatal and postnatal growth retardation, congenital muscular hypotonia, feeding difficulties in the neonatal period, motor and mental developmental delay, scoliosis, premature puberty, truncal obesity, short adult stature, small feet and hands as well as some nonspecific dysmorphic facial features such as almond-shaped eyes, broad nasal tip, micrognathia, high palate, short philtrum, and high forehead. IQ can be normal or reduced. Intellectual disability, if present, is usually mild to moderate. It is considered, due to relatively mild, overlapping, and unspecific symptoms, that some TS14 cases remain undetected [Ioannides et al., 2014; Severi et al., 2016]. This syndrome is caused by abnormal expression of imprinted genes at the chromosomal locus 14q32. UPD(14)mat is the molecular cause in about 78% of TS14 cases. UPD(14)mat may occur as isodisomy (2 identical homologous chromosomes inherited from 1 parent), heterodisomy (2 different homologous chromosomes inherited from 1 parent), or as a mixture of both [Zhang et al., 2016]. Most patients with UPD(14)mat also have concomitant balanced Robertsonian translocations or extra structurally abnormal chromosomes. Isolated methylation defects and paternal deletions of the imprinted locus 14q32 could be found in other TS14 cases [Ioannides et al., 2014; Kagami et al., 2017].

Trisomy of chromosome 14 is one of the autosomal trisomies where live birth in humans is only possible in mosaic form. It was described for the first time in 1975 by Rethoré et al. in a female newborn with multiple malformations. Growth retardation, motor and mental developmental delay, congenital heart defects, body and limb asymmetry, patterned skin hyperpigmentation, facial dysmorphism, microcephaly, and genitourinary abnormalities are the most frequent symptoms found in patients with mosaic trisomy 14. The most commonly described dysmorphic facial features are abnormal palpebral fissures, a prominent or broad forehead, broad nose, low-set ears, micrognathia, a short neck, and redundant neck skin folds. Most symptoms of mosaic trisomy 14 are nonspecific and frequently found in other mosaic chromosomal syndromes [von Sneidern and Lacassie, 2008; Salas-Labadia et al., 2014].

Both the UPD(14)mat-associated TS14 and mosaic trisomy 14 are very rare. The exact prevalence of these conditions is unknown, and there are less than 100 cases of TS14, and fewer than 50 cases of mosaic trisomy 14 described in the literature [Ioannides et al., 2014; Salas-Labadia et al., 2014; Kagami et al., 2017]. A molecularly and cytogenetically confirmed combination of UPD(14)mat and mosaic trisomy 14 have been currently reported only in 8 live-born cases [Antonarakis et al., 1993; Kayashima et al., 2002; Cox et al., 2004; Pecile et al., 2015; Stalman et al., 2015; Balbeur et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Ushijima et al., 2017].

Clinical Description

A 6-year-old girl, the second child of healthy and unrelated parents, was originally referred to genetic counseling because of a congenital heart defect, developmental delay, and dysmorphic features. Her family history was unremarkable for genetic diseases and congenital malformations. Pregnancy was complicated by intrauterine growth retardation and oligohydramnios. Because of fetal hypotrophy and a positive second-trimester screening test for aneuploidies, an amniocentesis was performed at the 20th week of pregnancy. The fetal karyotype was normal (46,XX), no trisomic cells or balanced chromosomal rearrangements were detected in 20 analyzed metaphases. She was born to a 32-year-old mother prematurely at the 35th week of gestation by emergency cesarean section because of pathological Doppler sonography. Her birth weight was 1,832 g (<10th centile; −1.5 SD), length 42 cm (<10th centile; −2 SD) and Apgar scores 7 and 8 at 1 and 5 min, respectively.

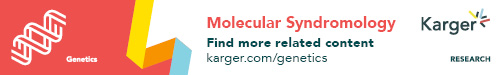

Shortly after birth, rough systolic murmur over the whole heart was noted and an atrioventricular septal defect with congestive heart insufficiency was diagnosed. Spinal X-ray with sonography of the brain and abdomen revealed no congenital malformations of spine, abdominal or pelvic organs. Pulmonary artery banding was performed at the age of 5 months. At the same age, a right-sided hemihypertrophy, limb-length difference (right hand and leg are longer) and increasing linear pigmentation on the arms and legs were noted (Fig. 1a, b, c, d, e). During the first years of life, the child had poor weight gain and feeding/sucking difficulties. She needed partial nasogastric tube feeding until the age of 6 months. After birth, her height, weight, and head circumference have always been below the 3rd centile or −2 SD. She was diagnosed with muscular hypotonia, progressive neuromuscular kyphoscoliosis (Fig. 1f, g), and severe psychomotor and cognitive developmental delay. At the corrected age of 1 year and 2 months, her motor skills were at the 6-month-old level; mental and social skills were less affected. She began to walk independently at 2.5 years of age. Neither brain MRI/MRS scan nor electroneuromyography revealed any abnormalities. Radical surgical correction of the atrioventricular septal defect was performed when she was 2.5 years old. Later, hyperopia and strabismus were also observed.

Fig. 1.

Clinical features of the proband at 4.5 years of age. a-c Growth retardation, body and face asymmetry, limb-length difference, dysmorphic facial features, short neck, small hands and feet, and genu valgum. d, e Linear hyperpigmentation on the arms and legs. f, g Severe neuromuscular kyphoscoliosis.

During the most recent workup, at the age of 6.0 years, her height was 93.3 cm (<<3rd centile; −5 SD), weight 15.6 kg (just below the 3rd centile; −2 SD), and her head circumference was 48 cm (<3rd centile; −2.5 SD). She was overweight (BMI >85th centile). Neuropsychological testing (NEPSY-II tests), performed at the age of 4 years and 8 months, showed that her cognitive development is at least 1 year behind and sensorimotor functions (fine motor skills and eye-hand coordination), short-term and long-term memory as well as expressive communication and visual-spatial abilities are below the expected level. Her receptive communication ability is also well below the expected level; analysis and synthesis skills are borderline. The girl has some dysmorphic features, such as upslanting palpebral fissures, short philtrum, asymmetrical face, a short neck, bilateral simian crease, small hands and feet as well as genu valgum (Fig. 1a, b, c). X-ray of the left hand revealed short middle phalanx of the little finger, a broad thumb, delayed bone age, and significantly decreased bone mineralization. The difference in leg length and thigh circumference is now approximately 2 cm. No signs of early-onset puberty have been noticed so far.

Because of severe progressive scoliosis and shorter left leg, the patient uses an individually fitted thoracolumbar plastic corset and orthopedic shoes. Vision problems are corrected with glasses, and surgery of extraocular muscles was performed. She works with a speech therapist and a physiotherapist. The patient does not have a growth hormone deficiency, but after careful consideration, the treatment with somatropin was started due to the small-for-gestational age with failure to catch up, extremely short stature, steady poor growth velocity (<3rd centile; <-2 SD), decreased bone mineralization, and the increased likelihood for early puberty [Ioannides et al., 2015]. After 1 year of treatment, the efficacy of growth hormone therapy will be re-evaluated including the possible impact on scoliosis.

Genetic Testing and Results

Because of congenital abnormalities, developmental delay, and dysmorphic features, chromosomal microarray (CMA) analysis was initially performed. It was carried out on DNA extracted from peripheral blood using a 300,000-SNP HumanCytoSNP-12 v2.1 BeadChip (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and analyzed using GenomeStudio software (Illumina, Inc.). CMA analysis revealed no copy number variations (CNVs), uniparental isodisomy or long contiguous stretches of homozygosity. As the patient has short stature and limb-length discrepancy, she was tested for 11p15-associated imprinting disorders.

Testing for Silver-Russell and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndromes (SRS/BWS) was done on blood DNA samples with methylation-specific multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MS-MLPA) analysis of the 11p15.5 region using SALSA MS-MLPA probemix ME030-B2 BWS/SRS (MRC-Holland, Inc., Amsterdam, Netherlands), according to the manufacturer's instructions. This analysis did not show any epigenetic alteration or CNVs in the imprinted region 11p15.5, and genetic testing was continued by whole exome sequencing (WES).

WES analysis was performed using Illumina HiSeq2500 platform in the Estonian Genome Center at the University of Tartu (EGCUT, Tartu, Estonia). WES revealed compound heterozygous mutations, c.1408C>T (p.Arg470Cys) and c.1573C>G (p.Gln525Glu; RefSeq NM_080618), in the CTCFL gene. The result was confirmed by bidirectional Sanger sequencing. No other definite or probable pathogenic mutations were detected. Sanger sequencing of parental DNA showed that the variant c.1573C>G is inherited from the mother, and the variant c.1408C>T is of paternal origin. The clinical significance of both mutations is uncertain. The paternal mutation has not been previously described in the dbSNP141, NHLBI GO ESP, ExAc, or 1000G/EA databases. The maternal mutation has been reported in these databases as a low-frequency variant (prevalence <5%). In silico analysis (PolyPhen-2, SIFT, MutationTaster, and CADD) classified both substitutions as likely deleterious variants. Although the CTCFL gene is not directly associated with any genetic disorder, it is believed to participate in some epigenetic mechanisms. Since the CTCFL gene has been found to be associated with the regulation of several imprinting control regions [Skaar et al., 2012] and the patient has growth retardation and body asymmetry typical for many imprinting disorders, an analysis of imprinted regions in chromosomes 6, 7, and 14 was additionally performed.

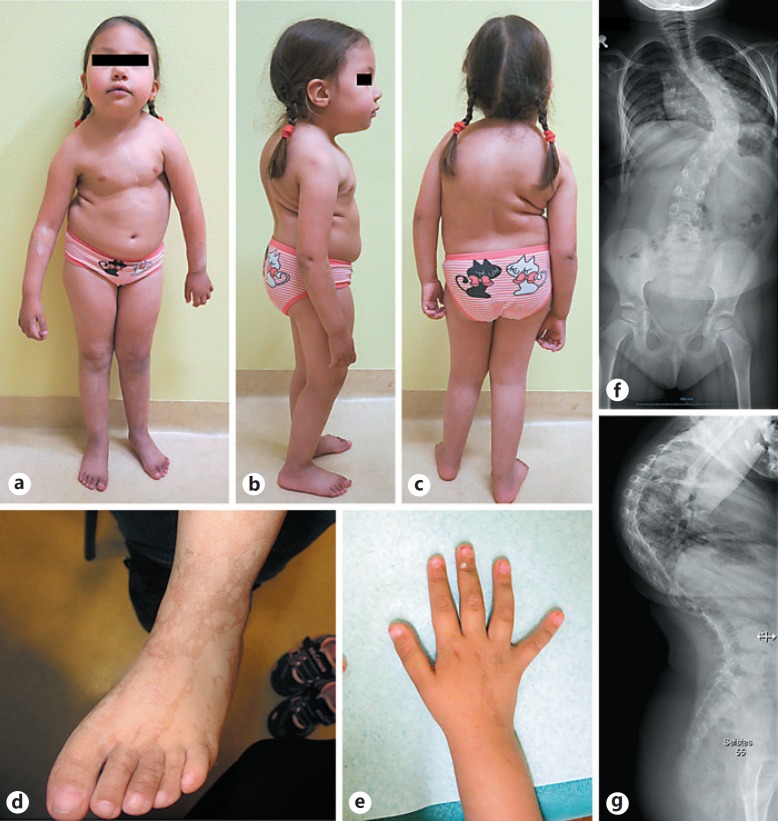

MS-MLPA analysis of imprinted genes in the chromosomal regions 6q24.2, 7p12.1, 7q32.2, and 14q32.2 was done using whole-blood DNA with SALSA MS-MLPA probemix ME032-A1-0313 UPD7-UPD14 (MRC-Holland, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The analysis revealed complete hypomethylation of the MEG3 gene in the imprinted region 14q32.2. Methylation ratios of all 3 probes in the MEG3 gene were close to zero (Fig. 2a). The same result was obtained using DNA extracted from hyperpigmented and normal skin fibroblasts, urine, and buccal swab. No CNVs or methylation alterations were found in other investigated regions. Because the analysis does not distinguish isolated hypomethylation of the MEG3 gene from UPD(14)mat, an additional analysis of maternal DNA was done.

Fig. 2.

Results of molecular and cytogenetic analyses. a Hypomethylation of the MEG3 gene in 14q32.2 found by MS-MLPA analysis of chromosomes 6, 7, and 14 (arrow). b In CNV analysis of the same MS-MLPA, the probes for the MEG3 gene are in the normal range, but the mean ratio of all probes for chromosome 14 is slightly elevated compared with ratio of probes in chromosomes 6 and 7 and probes of other tested individuals in the same run (arrows). c GTG-banded karyotype showing trisomy 14 indicated by an arrow. d FISH analysis of interphase nuclei using an MYC/IGH t(8;14) probe, showing 3 red signals of chromosomes 14 (arrows). e All 3 bands of the B allele frequency plot in the CMA analysis are wider and slightly split compared with another sample analyzed on the same chip (f).

Blood-derived DNA was analyzed by CMA using the same method and software as described above. Comparative analysis of the SNPs using the CMA results of the patient and her mother confirmed the diagnosis of maternal uniparental heterodisomy of the entire chromosome 14. UPD(14)mat-associated TS14 was diagnosed.

Later, due to atypical and unusually severe clinical presentation, a possibility of concomitant diagnosis was suspected. Since the congenital heart malformations and skin pigmentary anomalies are described in cases of mosaic trisomy 14, a chromosomal analysis of blood lymphocytes and skin fibroblasts was performed. Routine chromosomal analysis was done on metaphase chromosomes using G-banding, and FISH analysis was performed on interphase nuclei using MYC/IGH t(8;14) FISH probe (Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, UK). Both analyses did not reveal trisomy 14 in 50 metaphases and 150 interphases analyzed in both fibroblast cultures from normal and hyperpigmented skin biopsies. However, in hyperpigmented skin fibroblasts, 1 cell with trisomy 14 was detected by FISH, but because of the low reliability of the result, it was not reported. Routine chromosomal analysis of blood lymphocytes revealed trisomy 14 in 4% of the metaphases 47,XX,+14[2]/46,XX[48], and in about 7% of the interphase nuclei detected by FISH analysis, nuc ish 14q32×3[11]/14q32×2[139] (Fig. 2c, d). Chromosomal testing of other body tissues was refused by the family.

After establishment of the diagnosis, the results of CMA and MS-MLPA were retrospectively reviewed. It was noted that the log R ratio and B allele frequency in the CMA analysis were in the normal range, but compared with other samples analyzed on the same chip, all 3 bands of the B allele frequency plot are wider and slightly split (Fig. 2e, f). In CNV analysis of MS-MLPA of chromosomes 6, 7, and 14 done using blood DNA, the probes for the MEG3 gene are in the normal range, but the mean ratio of all probes for chromosome 14 is slightly elevated compared with the probe ratio in chromosomes 6 and 7 as well as probes of other tested individuals in the same run (Fig. 2b). All these features are likely evidence of low-level mosaicism of trisomy 14 in the patient's blood [Conlin et al., 2010].

Discussion

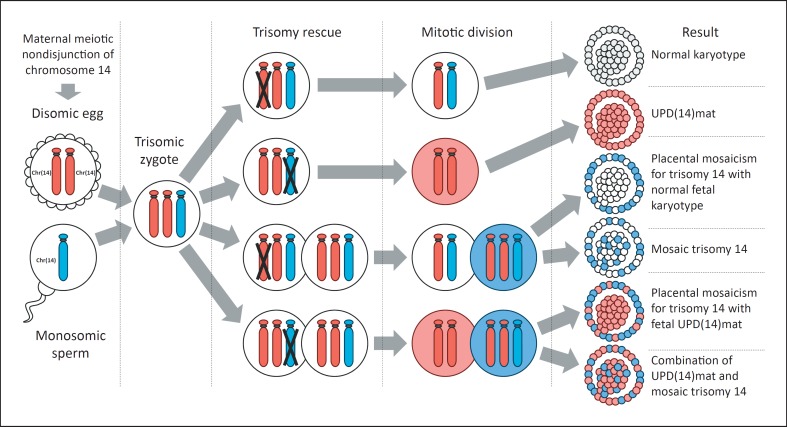

The coexistence of UPD(14)mat and mosaic trisomy 14 can be explained by the common mechanism of formation. While there are several possible formation mechanisms for both of these conditions, the maternal meiotic nondisjunction of chromosome 14 with subsequent mitotic loss of one extra chromosome 14 in a trisomic embryo (a process called trisomy rescue) is the common mechanism in both UPD(14)mat and mosaic trisomy 14 formation. In the case of mosaic trisomy 14, loss of the maternal chromosome 14 from a trisomic cell during mitotic division results in the formation of a new cell line with a normal karyotype. In turn, UPD(14)mat can arise through loss of the paternal chromosome 14 from the trisomic cell. In some cases, the formation of 2 cell lines, 1 with a UPD(14)mat and the other with a trisomy 14, is possible (Fig. 3). It is proposed that trisomic cells are often dysfunctional, have reduced replication rates, and could be lost during mitotic division [Wolstenholme, 1996]. This could be the reason why specifically low-level mosaicism for trisomy 14 has been detected in most of the described cases of both isolated mosaic trisomy 14 and UPD(14)mat-associated mosaic trisomy 14. The phenomenon of confined placental mosaicism, a condition characterized by the presence of chromosomally abnormal cells in the placenta but not in the embryo, is also observed in some cases of UPD(14)mat-associated TS14 in whom trisomy 14 was detected only in placenta samples [Towner et al., 2001].

Fig. 3.

Possible formation mechanism of UPD(14)mat and mosaic trisomy 14 through maternal meiotic nondisjunction of chromosome 14 and subsequent trisomy rescue (not all possible variants are shown).

To the best of our knowledge, our patient is the ninth described case of concomitant UPD(14)mat-associated TS14 and mosaic trisomy 14. Clinical features of previously reported cases, whose detailed description is available in the literature, are summarized in Table 1. Many nonspecific clinical symptoms, such as postnatal growth retardation, muscular hypotonia, motor and mental developmental delay as well as facial dysmorphism, are characteristic for both UPD(14)mat and mosaic trisomy 14. These features are present in almost all cases. Typical for TS14, intrauterine growth retardation, low birth weight or length, feeding difficulties, and obesity are observed in ≥75% of the patients. More specific TS14 symptoms, such as scoliosis, early-onset puberty, and hyperextensible joints, are present only in some described cases. Specific features of mosaic trisomy 14 are relatively rare, being present in 12.5–37.5% of the patients. The most frequently described signs of trisomy 14 are congenital heart defects, body or limb asymmetry, and pigmentary skin lesions, all present in our patient. The rarity of trisomy 14 features can probably be explained by their overlap with TS14 symptoms and by a low percentage of trisomic cells in the body.

Table 1.

Summary of the clinical features of previously reported cases with concomitant UPD(14)mat and mosaic trisomy 14

| Clinical findings | Our case | Antonarakis et al., 1993 | Kayashima et al., 2002 | Cox et al., 2004 | Stalman et al., 2015 | Balbeur et al., 2016 | Zhang et al., 2016 | Ushijima et al., 2017 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPD(14)mat | |||||||||

| IUGR/low birth weight or length | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | 7/8 |

| Feeding difficulties | + | + | NM | + | NM | + | + | + | 6/8 |

| Scoliosis | + | + | − | NM | NM | NM | + | − | 3/8 |

| Early-onset/premature puberty | −a | + | − | + | −b | + | −c | −d | 3/8 |

| Hyperextensible joints | − | + | NM | NM | + | + | NM | NM | 3/8 |

| Overweight/truncal obesity | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | 7/8 |

| Overlapping symptoms | |||||||||

| Postnatal growth retardation | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 8/8 |

| Muscular hypotonia | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | 7/8 |

| Motor developmental delay | + | + | NM | + | + | + | − | + | 6/8 |

| Mental delay/mental retardation | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | 7/8 |

| Facial dysmorphism | + | + | NM | + | + | + | + | + | 7/8 |

| Mosaic trisomy 14 | |||||||||

| Congenital heart defects/problems | + | − | NM | NM | NM | + | − | + | 3/8 |

| Body/limb asymmetry | + | + | NM | NM | NM | NM | + | − | 3/8 |

| Pigmentary skin lesions | + | NM | NM | NM | NM | + | + | − | 3/8 |

| Microcephaly | + | − | NM | NM | NM | NM | − | − | 1/8 |

| Genitourinary abnormalities | − | − | NM | NM | NM | NM | + | − | 1/8 |

| Eye abnormalities/vision problems | + | − | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | + | 2/8 |

| Level of trisomy 14 mosaicism | 4 – 7% | 5% | 7→0.8%e | low level | low level | 2 – 49% | 1 – 20% | 0.6 – 47.1% | |

+, present; −, absent; NM, not mentioned. Early-onset/premature puberty was not present at:

6 years

7 years

9 years, and

3 years of age.

The percentage of trisomy 14 cells in peripheral blood lymphocytes from the patient was 7% at the age of 21 months, but decreased to 0.8% at 20 years of age.

Interestingly, we were unable to detect trisomy 14 cells, neither in the hyperpigmented skin samples nor in the samples of normal skin. At the same time, it is known that no direct correlation has been found between the abnormal skin pigmentation and chromosome 14 trisomy mosaicism in fibroblasts. The literature describes patients with absence of trisomy 14 in the abnormal skin samples [Lynch et al., 2004] and patients with the presence of identical level of trisomy 14 mosaicism in both hyperpigmented and normal skin [Salas-Labadia et al., 2014; Balbeur et al., 2016]. The presence of trisomic cells in the skin fibroblasts of individuals without pigmentary skin lesions is also reported [Petersen et al., 1986; Merritt and Natarajan, 2007]. Thus, it is unclear which genetic event causes increasing linear pigmentation in our patient. Significantly reduced replication rates of trisomic cells in fibroblast culture could theoretically also be the reason for the false-negative cytogenetic result.

Notably, the neuromuscular scoliosis found in our patient is unusually severe and progressive compared with scoliosis described in the typical cases of TS14. It can be assumed that asymmetry of muscle tone or length caused by mosaic trisomy 14 could also be one of the etiological factors of the condition in our case.

It is worth noting that our patient's diagnosis was achieved due to variants of uncertain significance in the CTCFL gene detected by WES analysis, which led us to examine the patient for congenital imprinting disorders. Now, considering the final diagnosis and possible formation mechanisms of the conditions found, we can conclude that the revealed compound heterozygous mutations in the CTCFL gene are an incidental finding and not associated with the patient's disease.

In summary, it is likely that the described combination of 2 etiologically related conditions is actually more prevalent. Because of low-level mosaicism and unequal distribution of abnormal cells in different body tissues, the diagnosis of mosaic trisomy 14 can be very complicated. Additional chromosomal and molecular investigations are indicated for every patient with UPD(14)mat-associated TS14 with atypical clinical presentation.

Statement of Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents for publication of the clinical data and accompanying images. All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Tartu University Hospital and Research Ethics Committee of the University of Tartu.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the family for their cooperation. This work was supported by the Estonian Research Council grant PUT355.

References

- Antonarakis SE, Blouin JL, Maher J, Avramopoulos D, Thomas G, Talbot CC., Jr Maternal uniparental disomy for human chromosome 14, due to loss of a chromosome 14 from somatic cells with t(13;14) trisomy 14. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;52:1145–1152. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbeur S, Grisart B, Parmentier B, Sartenaer D, Leonard PE, et al. Trisomy rescue mechanism: the case of concomitant mosaic trisomy 14 and maternal uniparental disomy 14 in a 15-year-old girl. Clin Case Rep. 2016;4:265–271. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlin LK, Thiel BD, Bonnemann CG, Medne L, Ernst LM, et al. Mechanisms of mosaicism, chimerism and uniparental disomy identified by single nucleotide polymorphism array analysis. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:1263–1275. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox H, Bullman H, Temple IK. Maternal UPD(14) in the patient with a normal karyotype: clinical report and a systematic search for cases in samples sent for testing for Prader-Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;127A:21–25. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannides Y, Lokulo-Sodipe K, Mackay DJG, Davies JH, Temple IK. Temple syndrome: improving the recognition of an underdiagnosed chromosome 14 imprinting disorder: an analysis of 51 published cases. J Med Genet. 2014;51:495–501. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagami M, Nagasaki K, Kosaki R, Horikawa R, Naiki Y, et al. Temple syndrome: comprehensive molecular and clinical findings in 32 Japanese patients. Genet Med. 2017;19:1356–1366. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayashima T, Katahira M, Harada N, Miwa N, Ohta T, et al. Maternal isodisomy for 14q21-q24 in a man with diabetes mellitus. Am J Med Genet. 2002;111:38–42. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch MF, Fernandes CJ, Shaffer LG, Potocki L. Trisomy 14 mosaicism: a case report and review of the literature. J Perinatol. 2004;24:121–123. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt TA, Natarajan G. Trisomy 14 mosaicism: a case without evidence of neurodevelopmental delay and a review of the literature. Am J Perinatol. 2007;24:563–566. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-986691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecile V, Cleva L, Fabretto A, Cappellani S, Bedon L, Lenzini E. Frequency of uniparental disomy in 836 patients with pathological phenotype. Chromosome Res. 2015;23(Suppl 1):S52–53. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen MB, Vejerslev LO, Beck B. Trisomy 14 mosaicism in a 2-year-old girl. J Med Genet. 1986;23:86–88. doi: 10.1136/jmg.23.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rethoré MO, Couturier J, Carpentier S, Ferrand J, Lejeune J. Mosaic 14 trisomy in a female child with multiple abnormalities (in French) Ann Genet. 1975;18:71–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Labadia C, Lieberman E, Cruz-Alcivar R, Navarrete-Meneses P, Gómez S, et al. Partial and complete trisomy 14 mosaicism: clinical follow-up, cytogenetic and molecular analysis. Mol Cytogenet. 2014:7–65. doi: 10.1186/s13039-014-0065-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severi G, Bernardini L, Briuglia S, Bigoni S, Buldrini B, et al. New patients with Temple syndrome caused by 14q32 deletion: genotype-phenotype correlations and risk of thyroid cancer. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170A:162–169. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaar DA, Li Y, Bernal AJ, Hoyo C, Murphy SK, Jirtle RL. The human imprintome: regulatory mechanisms, methods of ascertainment, and roles in disease susceptibility. ILAR J. 2012;53:341–358. doi: 10.1093/ilar.53.3-4.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalman SE, Kamp GA, Hendriks YMC, Hennekam RCM, Rotteveel J. Positive effect of growth hormone treatment in maternal uniparental disomy chromosome 14. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2015;83:671–676. doi: 10.1111/cen.12841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple IK, Cockwell A, Hassold T, Pettay D, Jacobs P. Maternal uniparental disomy for chromosome 14. J Med Genet. 1991;28:511–514. doi: 10.1136/jmg.28.8.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towner DR, Shaffer LG, Yang SP, Walgenbach DD. Confined placental mosaicism for trisomy 14 and maternal uniparental disomy in association with elevated second trimester maternal serum human chorionic gonadotrophin and third trimester fetal growth restriction. Prenat Diagn. 2001;21:395–398. doi: 10.1002/pd.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushijima K, Yatsuga S, Nakamura A, Koga Y, Fukami M, Kagami M. A 3-year-old girl with 46,XX,upd(14)mat/47,XX,+14 mosaicism. 2017 European Human Genetics Conference, May 27–30, Copenhagen [Google Scholar]

- von Sneidern E, Lacassie Y. Is trisomy 14 mosaic a clinically recognizable syndrome? - case report and review. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:1609–1613. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolstenholme J. Confined placental mosaicism for trisomies 2, 3, 7, 8, 9, 16, and 22: their incidence, likely origins, and mechanisms for cell lineage compartmentalization. Prenat Diagn. 1996;16:511–524. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199606)16:6<511::AID-PD904>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Qin H, Wang J, OuYang L, Luo S, et al. Maternal uniparental disomy 14 and mosaic trisomy 14 in a Chinese boy with moderate to severe intellectual disability. Mol Cytogenet. 2016:9–66. doi: 10.1186/s13039-016-0274-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]