Abstract

Dibutyryl adenosine cyclophosphate (dbcAMP-Ca), an analog of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), plays greater roles in regulating physiological activities and energy metabolism than cAMP. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of oral administration of dbcAMP-Ca on growth performance and fatty acids metabolism in weaning piglets. A total of 14 early weaning piglets (7 ± 1 d of age, 3.31 ± 0.09 kg, Landrace × Large White × Duroc) were randomly divided into 2 groups: control group and dbcAMP-Ca group, and the piglets received 7 mL of 0.9% NaCl or 1.5 mg dbcAMP-Ca dissolved in 7 mL of 0.9% NaCl per day for 10 d, respectively. The results showed that the average daily gain (ADG) increased by 109.17% (P < 0.05) in the dbcAMP-Ca group compared with the control group. Besides, dbcAMP-Ca significantly decreased blood high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLC) concentration (P < 0.05) and significantly increased blood low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLC) concentration (P < 0.05) compared with the control group. Further, liver C18:2n6t content significantly increased in dbcAMP-Ca group (P < 0.05) compared with the control group. With the increase of C18:2n6t content, the mRNA expression levels of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) and hormone sensitive glycerol three lipase (HSL), of which genes are related to lipid metabolism, were also significantly increased (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01). All of the results indicated that dbcAMP-Ca improved the ADG, which was probably done by regulating fatty acids metabolism in the liver of weaning piglets.

Keywords: Dibutyryl adenosine cyclophosphate, Growth performance, Lipid metabolism, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α, Hormone sensitive glycerol three lipase, Early weaning piglets

1. Introduction

Neonatal piglets face heavy challenge to adapt to the shift between intrauterine and extrauterine environments because of weak gut absorptive capacity, low immunity and adaptability, etc (Tanghe et al., 2014, Wang et al., 2017). Normally, weaning usually occurred in an early period at around 21 d of age. However, under the integrated production, weaning time of piglets gets earlier and earlier. Weaning in piglets may lead to worse situation and result in weaning stress in piglets, thus may affect their health and welfare with a decline in feed intake and be vulnerable to disease (Duan et al., 2015).

Milk lipids are the main sources of energy for sucking piglets. An earlier study has found that respiratory entropy of newborn piglets was reduced after birth which indicated that piglets used large amounts of fatty acids to provide energy (Hales, 1997). A former study also showed that lipids in the milk provided nearly 50% of the energy for suckling piglets (Hobbins, 1997). However, it has been reported that the activity of pancreatic lipase increased with age but weaning made it sharply decline (Aumaitre and Corring, 1978, Cera et al., 1990). Therefore, fatty acid, 1 of the 3 major nutrients, plays significant roles in growth, metabolism and physiological functions in newborn mammals because of their considerable energy needs and defective dietary capacity (Gruppuso et al., 1994, Hardy and Kleinman, 1994, Goodyer et al., 2001). Herein, the decomposition and utilization of fatty acids are of great significance to newborn piglets.

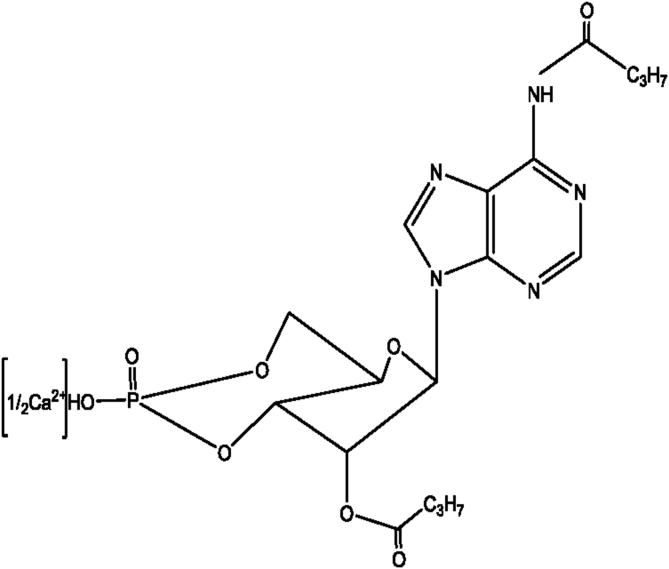

Interestingly, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), which has been shown to mediate the hormonal regulation of lipid metabolism (Butcher et al., 1968, Gagelin et al., 1999), is vital in regulating and utilizing fatty acids (Luiken et al., 2002, Madsen et al., 2008). Moreover, dibutyryl adenosine cyclophosphate calcium (dbcAMP-Ca, Fig. 1), an analog of cAMP, can regulate the lipid metabolism remarkably in growing and finishing pigs (Gao et al., 2004), and affect the differentiation of sheep inguinal preadipocytes (Kong et al., 2017). However, little is known about how dbcAMP affects the metabolism of fatty acids and the growth performance in weaning piglets. Therefore, the present study was intended to seek the effect of oral administration of dbcAMP-Ca on growth performance and lipid fatty acids metabolism in weaning piglets.

Fig. 1.

The structural formula of dibutyryl adenosine cyclophosphate (dbcAMP-Ca).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and treatments

The animal experiment was approved by the Protocol Management and Review Committee of the institute of Subtropical Agriculture, Chinese Academy of Science. Pigs were cared for and slaughtered according to the guidelines of the institute of Subtropical Agriculture on Animal Care, Changsha, China. Dibutyryl adenosine cyclophosphate (dbcAMP-Ca) (C18H23N5O8PCa, molecular weight 507.00 g/mol, purity 98.00%) was provided by Meiya Haian pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (Haian 226600, China).

Fourteen 7-day-old weaning piglets (Landrace × Large White × Duroc) with mean body weight at 3.31 ± 0.09 kg were randomly divided into 2 groups: control group and dbcAMP-Ca group. The piglets received 7 mL of 0.9% NaCl or 1.5 mg dbcAMP-Ca dissolved in 7 mL of 0.9% NaCl by oral administration at indicated times per day for 10 days, respectively. Ingredients and nutrient levels of the basal milk are shown in Table 1. All the piglets were fed by artificial breast feeder and had ad libitum access to water and the basal milk.

Table 1.

Ingredients (%) and nutrient levels (%) of the basal milk (air-dry basis).

| Ingredients | Content | Nutrient levels | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skimmed milk powder | 85.0 | DE, MJ/kg | 14.65 |

| Dried whey | 5.0 | CP | 20.50 |

| Glucose | 2.5 | Ca | 0.70 |

| Plasma proteins | 3.5 | Total P | 0.60 |

| Premix1 | 4.0 | Lys | 1.45 |

| Total | 100.0 | Met | 0.48 |

| Try | 0.29 |

The premix provided the following for per kg of the basal milk: vitamin A1 500 IU, vitamin D3 200 IU, vitamin E 85 IU, D-pantothenic acid 35 mg, vitamin B2 12 mg, folic acid 1.5 mg, nicotinic acid 35 mg, vitamin B 13.5 mg, vitamin B6 2.5 mg, biotin 0.2 mg, vitamin B12 0.05 mg, copper (as copper sulfate) 15 mg, ferrum (as ferrous sulfate) 100 mg, manganese (as manganese sulfate) 20 mg, iodate (as calcium iodate) 1.0 mg, selenium (as sodium selenite) 0.35 mg, cobalt (as cobalt sulfate) 0.2 mg, and chromium (as chromium picolinate) 0.2 mg.

2.2. Samples collection

Before slaughter, 5 mL blood samples were collected from the jugular vein, and plasma samples were obtained by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, followed by being immediately stored at −80 °C for later lipid profiles analysis (Wu et al., 2016). Liver samples were taken from each animal, followed by being flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C prior to RNA isolation and at −20 °C for fatty acid analysis, respectively.

2.3. Fatty acids analysis in liver of piglets

The extraction of fatty acids from 500 mg of the liver tissue and the methylation were performed. The concentration of individual fatty acids was quantified according the peak area and expressed as a percentage of total fatty acids by gas chromatography (GC-2010, Shimadzu Corp, Japan) as previously described (Tan et al., 2009, Raj et al., 2010).

2.4. RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

About 100 mg of the liver tissue was pulverized in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was isolated from the homogenate using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA). The concentration of total RNA was quantified spectrophotometrically (NanoDrop ND-1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, DE, USA) at 260 nm, and the ratio of 260 nm to 280 nm was used to assess RNA quality, then cDNA synthesis was carried out using a PrimeScript RT reagent Kit With gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). Primers (Table 2) were designed by Primer 5.0 based on GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), and Oligo Synthesis was conducted by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). β-actin was chosen as a reference gene.

Table 2.

Primer design parameters.

| Genes | Primers | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Size, bp |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | Forward Reverse |

TGCGGGACATCAAGGAGAAG AGTTGAAGGTGGTCTCGTGG |

216 |

| FAS | Forward Reverse |

GTCCTGCTGAAGCCTAACTC TCCTTGGAACCGTCTGTG |

206 |

| PPARα | Forward Reverse |

GCTATCATTTGGTGCGGAGAC GGAGTTTGGGGAAGAGAAAGAC |

139 |

| CPT-1α | Forward Reverse |

CCATCAAAACTGCCTTCCTTAG AGCGAGTGTGCCAGATACAAA |

118 |

| CPT-1β | Forward Reverse |

TTCCGCCAAACCTTGAAACT GGACACAGATAGCCCAGACTTT |

100 |

| ACCα | Forward Reverse |

TCCCAGTGCAAGCAGTATG TGCCAATCCACACGAAGAC |

211 |

| HSL | Forward Reverse |

GAAGGGAGAGCTATGGCACC CTCACACTCTCCAAGCCCAG |

130 |

FAS = fatty acid syntheses; PPARα = peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α; CPT-1α = carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1α; CPT-1β = carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1β; ACCα = acetyl-coA carboxylase α; HSL = hormone sensitive glycerol three lipase.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The data are presented as means ± SEM. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The differences among groups were evaluated using independent t test. P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 were considered statistically significant and extremely significant, respectively.

3. Results

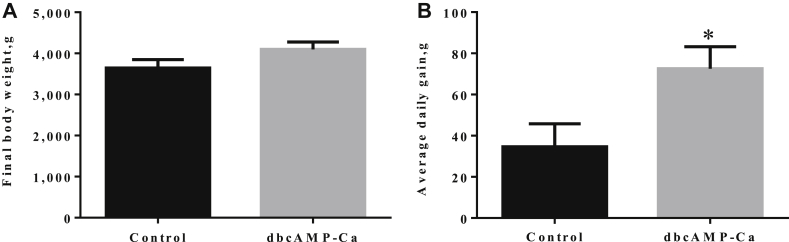

3.1. Growth performance

As shown in Fig. 2, compared with the control group, dbcAMP-Ca increased the final weight gain by 12.06% (P > 0.05) and average daily gain (ADG) by 109.17% (P < 0.05) in early weaning piglets.

Fig. 2.

Effect of dibutyryl adenosine cyclophosphate (dbcAMP-Ca) on the final body weight (A) and average daily gain (B) of weaning piglets (n = 7). * indicates a significant difference (P < 0.05) between the control group and dbcAMP-Ca group.

3.2. Blood lipid profiles

As shown in Table 3, low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLC) concentration increased while high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLC) concentration decreased in dbcAMP-Ca treated piglets compared with the control group (P < 0.05). Triglyceride (TG) and total cholesterol (TC) concentrations in dbcAMP-Ca group decreased by 3.64% and 11.11%, respectively (P > 0.05) compared to the control group.

Table 3.

Blood lipid profiles (mmol/L) of piglets (n = 7).

| Item | Groups1 |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | dbcAMP-Ca | ||

| TC | 2.47 ± 0.15 | 2.38 ± 0.12 | 0.65 |

| TG | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 0.32 ± 0.04 | 0.56 |

| HDLC | 1.21 ± 0.07∗ | 1.03 ± 0.04 | 0.04 |

| LDLC | 0.80 ± 0.07 | 0.93 ± 0.07∗ | 0.03 |

| T-bil | 20.07 ± 2.06 | 21.39 ± 4.76 | 0.80 |

| D-bil | 2.54 ± 0.50 | 1.97 ± 0.88 | 0.51 |

| TBA | 24.17 ± 6.57 | 14.07 ± 2.69 | 0.18 |

dbcAMP-Ca = dibutyryl adenosine cyclophosphate; TC = total cholesterol; TG = triglyceride; HDLC = high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDLC = low density lipoprotein cholesterol; T-bil = total bilirubin; D-bil = bilirubin direct; TBA = total bile acid.

* Indicates a significant difference (P < 0.05) between the control group and dbcAMP-Ca group.

Control group: a basal diet; dbcAMP-Ca group: the basal diet supplemented with 1.5 mg/d of dbcAMP-Ca.

3.3. Liver fatty acids composition

As shown in Table 4, compared with the control group, the liver content of C12:0 decreased by 57.89% (P < 0.05), and those of monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) C18:1n9t and C18:1n9c decreased by 12.50% and 5.14% (P > 0.05) in dbcAMP-Ca group, respectively. Meanwhile, the liver content of C18:3n3 decreased by 29.41% in dbcAMP-Ca group (P > 0.05), and that of C18:2n6t increased by 30.00% in dbcAMP-Ca group (P < 0.05) compared with the control group.

Table 4.

Long chain fatty acid content (%) in liver (n = 7).

| Item | Groups1 |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | dbcAMP-Ca | ||

| C10:0 | 0.02 ± 0.003 | 0.02 ± 0.003 | 0.69 |

| C12:0 | 0.19 ± 0.03 | 0.08 ± 0.03∗ | 0.03 |

| C14:0 | 0.78 ± 0.07 | 0.55 ± 0.27 | 0.09 |

| C15:0 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.34 |

| C16:0 | 15.34 ± 0.44 | 15.73 ± 0.56 | 0.59 |

| C17:0 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 0.75 |

| C18:0 | 21.24 ± 0.61 | 22.21 ± 1.08 | 0.47 |

| C20:0 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.61 |

| C16:1 | 0.91 ± 0.21 | 0.93 ± 0.37 | 0.94 |

| C17:1 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.23 |

| C18:1n9t | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.04 | 0.79 |

| C18:1n9c | 17.73 ± 0.98 | 16.77 ± 0.75 | 0.45 |

| C18:2n6t | 0.01 ± 0.003 | 0.013 ± 0.008∗ | 0.04 |

| C18:2n6c | 15.95 ± 0.37 | 16.07 ± 0.67 | 0.88 |

| C18:3n6 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.76 |

| C18:3n3 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 0.14 |

| C20:1 | 0.31 ± 0.03 | 0.28 ± 0.03 | 0.47 |

| C20:3n6 | 2.45 ± 0.20 | 2.53 ± 0.32 | 0.83 |

| C20:4n6 | 17.67 ± 0.37 | 17.36 ± 0.82 | 0.76 |

| C22:6n6 | 6.40 ± 0.30 | 6.49 ± 0.23 | 0.82 |

| SFA | 39.12 ± 0.6 | 40.00 ± 0.70 | 0.28 |

| MUFA | 17.82 ± 0.98 | 16.85 ± 0.76 | 0.44 |

| PUFA | 80.52 ± 0.86 | 77.48 ± 1.11 | 0.08 |

* Indicates a significant difference (P < 0.05) between the control group and dbcAMP-Ca group.

Control group: a basal diet; dbcAMP-Ca group: the basal diet supplemented with 1.5 mg/d of dbcAMP-Ca.

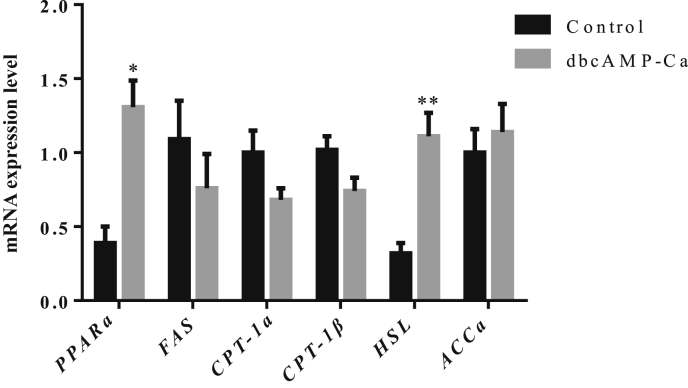

3.4. mRNA expression levels of lipid metabolism related genes

To further confirm the role of lipid metabolism in the liver, the mRNA expression levels of the lipid metabolism related genes, fatty acid syntheses (FAS), hormone sensitive glycerol three lipase (HSL), acetyl-coA carboxylase α (ACCα), carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1α (CPT-1α), carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1β (CPT-1β), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα), were detected by qRT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 3, compared with the control group, dbcAMP-Ca significantly increased the mRNA expression level of PPARα (P < 0.05) and extremely significantly increased that of HSL (P < 0.01) in the liver of piglets. However, there were no differences between the control group and dbcAMP-Ca group for the mRNA expression levels of FAS, ACCα, CPT-1α and CPT-1β.

Fig. 3.

Effect of dibutyryl adenosine cyclophosphate (dbcAMP-Ca) on the mRNA expression levels of lipid metabolism related genes in liver (n = 7). PPARα = peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α; FAS = fatty acid syntheses; CPT-1α = carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1α; CPT-1β = carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1β; ACCα = acetyl-coA carboxylase α; HSL = hormone sensitive glycerol three lipase. * and ** indicate significant difference (P < 0.05) and extreamly significant difference (P < 0.01) between the control group and dbcAMP-Ca group, respectively.

4. Discussion

Dibutyryl adenosine cyclophosphate (dbcAMP-Ca), as an analog of cAMP, exerts effects via stimulating cAMP signaling pathway (Arnold et al., 2010), such as cell proliferation and differentiation, hormones release and regulation (Boghaert et al., 1991, Chrenek et al., 2010, Chrenek et al., 2013). And former studies have also found that growth hormone could be better stimulated through Ca 2+ and cAMP-dependent interactive mechanism thus enhance the production performance of animals (Sartin et al., 1996, Pahan et al., 1998). In this study, the supplement of dbcAMP-Ca significantly increased the ADG and promoted the growth of early weaning piglets, which might be caused by the interactive effect of Ca2+ and dbcAMP.

Lipid, as a kind of necessary substance for animals, plays a vital role in maintaining cell structure and function (Smith et al., 2003, Liu et al., 2017). Blood lipid concentrations were regarded as the status of dynamic lipid absorption and nutritional in animals and humans (Li et al., 2016). Notably, increasing levels of blood constituents are associated with the increasing of dietary nutrients (Brungardt, 1963, Sink et al., 1973). In this regard, the current result of the elevated blood concentrations of LDLC and HDLC was influenced by dbcAMP-Ca treatment when compared with the control group. In our results, LDLC increased while HDLC decreased, which seemingly shows lipid metabolic disturbance and it might confer the risk for cardiovascular disease according to the former studies (Gupta and Rajagopal, 2007, Shin, 2009). However, for the fast growing piglets, high concentrations of LDLC and low HDLC may represent a high level of nutrition, which is in line with the significant change in the ADG. Furthermore, fatty acids composition in the liver also reflects the changes in fatty acid metabolism. The contents of polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) and MUFA decreased whereas the content of saturated fatty acid (SFA) increased in dbcAMP-Ca group when compared with the control group, and this could be explained by the high LDLC and low HDLC in blood. According to the former studies, the proportion of PUFA is affected by many factors, such as synthesis rate, and mutual conversion (Enser et al., 2000). Besides, PUFA can be oxidized to supply energy to the organism (Tebbey et al., 1994, Clarke, 2000). Our study indicated that the supplement of dbcAMP-Ca could promote the oxidation of PUFA and might provide energy for piglets to meet the requirements of growth and development. For the further researches on lipid metabolism in the liver, we detected the mRNA expression levels of lipid metabolism related genes. Hormone sensitive glycerol three lipase is a rate-limited enzyme in triglyceride decomposition which cleaves fatty acids from triglycerides and diglycerides (Watt, 2013). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) has been regarded as the major regulators of lipid metabolism (Ajuwon et al., 2003). Triglyceride (TG) is synthesized via FAS catalyzing acetyl coenzyme A and malonate coenzyme A. Moreover, it is the major form required for body fat deposition (Semenkovich, 1997, Yan et al., 2002). In this experiment, dbcAMP-Ca increased the mRNA expression levels of PPARα and HSL in the liver, which indicated that the addition of dbcAMP-Ca mainly promoted lipolysis and inhibited lipid deposition in the liver, thereby promoted the usage of milk lipids, and thus provided more energy for suckling piglets (Luiken et al., 2002, Madsen et al., 2008, Jia et al., 2018).

Taken together, oral administration of dbcAMP-Ca can significantly increase the weight gain of piglets and affect blood HDLC and LDLC concentrations, decrease the content of PUFA and enhance metabolism of fatty acids in the liver, which may be through the decomposition of lipids by PPARα and HSL in the liver to provide more energy to ensure the healthy growth of piglets.

5. Conclusions

Conclusively, the present study suggests that dbcAMP-Ca has a significant effect on the growth performance mainly by its regulation effects on lipid metabolism. In the future, more well-designed researches will be needed to investigate the effects of dbcAMP-Ca on early weaning piglets.

Conflicts of interest

We declare that we have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work, there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service and/or company that could be construed as influencing the content of this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was jointly supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0501209, and 2016YFD0500504), the Earmarked Fund for China Agriculture Research System (CARS-35) and the Major Project of Hunan Province (2016NK2124; 2015NK1002).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

Contributor Information

Chunyan Xie, Email: xiechunyan@hunau.edu.cn.

Zhiyong Fan, Email: fzyong04@163.com.

References

- Ajuwon K.M., Kuske J.L., Anderson D.B., Hancock D.L., Houseknecht K.L., Adeola O. Chronic leptin administration increases serum NEFA in the pig and differentially regulates PPAR expression in adipose tissue. J Nutr Biochem. 2003;14:576–583. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(03)00104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold D.E., Gagne C., Niknejad N., McBurney M.W., Dimitroulakos J. Lovastatin induces neuronal differentiation and apoptosis of embryonal carcinoma and neuroblastoma cells: enhanced differentiation and apoptosis in combination with dbcAMP. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;345:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0553-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumaitre A., Corring T. Development of digestive enzymes in the piglet from birth to 8 weeks. II. Intestine and intestinal disaccharidases. Nutr Metab. 1978;22:244–255. doi: 10.1159/000300539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boghaert E.R., Simpson J., Jacob R.J., Lacey T., Walsh J.W., Zimmer S.G. The effect of dibutyryl camp (dBcAMP) on morphological differentiation, growth and invasion in vitro of a hamster brain-tumor cell line: a comparative study of dBcAMP effects in 2- and 3-dimensional cultures. Int J Cancer. 1991;47:610–618. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910470422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brungardt T.F. The hi-riding contact lens. Optom Wkly. 1963;54:1409–1414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher R.W., Baird C.E., Sutherland E.W. Effects of lipolytic and antilipolytic substances on adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate levels in isolated fat cells. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:1705–1712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cera K.R., Mahan D.C., Reinhart G.A. Effect of weaning, week postweaning and diet composition on pancreatic and small intestinal luminal lipase response in young swine. J Anim Sci. 1990;68:384–391. doi: 10.2527/1990.682384x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrenek P., Grossmann R., Sirotkin A.V. The cAMP analogue, dbcAMP affects release of steroid hormones by cultured rabbit ovarian cells and their response to FSH, IGF-I and ghrelin. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;640:202–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrenek P., Makarevich A.V., Balazi A., Fazekasova J., Schlarmannova J., Matejovicova B. The effect of the cAMP analogue, dbcAMP, on proliferation and apoptosis of rabbit oviductal cells. Folia Biol (Krakow) 2013;61:247–252. doi: 10.3409/fb61_3-4.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke S.D. Polyunsaturated fatty acid regulation of gene transcription: a mechanism to improve energy balance and insulin resistance. Br J Nutr. 2000;1:S59. doi: 10.1017/s0007114500000969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y., Li F., Tan B., Lin B., Kong X., Li Y. Myokine interleukin-15 expression profile is different in suckling and weaning piglets. Anim Nutr. 2015;1:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enser M., Richardson R.I., Wood J.D., Gill B.P., Sheard P.R. Feeding linseed to increase the n-3 PUFA of pork: fatty acid composition of muscle, adipose tissue, liver and sausages. Meat Sci. 2000;55:201–212. doi: 10.1016/s0309-1740(99)00144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagelin C., Toru-Delbauffe D., Gavaret J.M., Pierre M. Effects of cyclic AMP on components of the cell cycle machinery regulating DNA synthesis in cultured astrocytes. J Neurochem. 1999;73:1799–1805. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S., Ren X., Liu C., Yin G., Zhang X., Cheng M. Regulation of dbcAMP on lipid and protein metabolism in pigs. Chinese J Vet. 2004;24:62–65. [Google Scholar]

- Goodyer C.G., Figueiredo R.M., Krackovitch S., De Souza Li L., Manalo J.A., Zogopoulos G. Characterization of the growth hormone receptor in human dermal fibroblasts and liver during development. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;281:E1213–E1220. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.6.E1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruppuso P.A., Boylan J.M., Bienieki T.C., Curran T.R. Evidence for a direct hepatotrophic role for insulin in the fetal rat: implications for the impaired hepatic growth seen in fetal growth retardation. Endocrinol. 1994;134:769–775. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.2.8299572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S., Rajagopal G. The significance of plasma high density lipoprotein cholesterol (hdlc) Nepal Med Coll J. 2007;9:212–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales C.N. Metabolic consequences of intrauterine growth retardation. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1997;423:184–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb18410.x. discussion 188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy S.C., Kleinman R.E. Fat and cholesterol in the diet of infants and young children: implications for growth, development, and long-term health. J Pediatr. 1994;125:S69–S77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(06)80739-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbins J. Morphometry of fetal growth. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1997;423:165–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb18403.x. discussion 169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia D., Li Z., Gao Y., Feng Y., Li W. A novel triazine ring compound (MD568) exerts in vivo and in vitro effects on lipid metabolism. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;103:790–799. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong D., Cui J., Fu J. DbcAMP regulates adipogenesis in sheep inguinal preadipocytes. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16:93. doi: 10.1186/s12944-017-0478-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Li F., Chen S., Duan Y., Guo Q., Wang W. Protein-restricted diet regulates lipid and energy metabolism in skeletal muscle of growing pigs. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64:9412–9420. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b03959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Yang T., Pan T., Liu C., Li S. Effect of low-selenium/high-fat diet on pig peripheral blood lymphocytes: perspectives from selenoproteins, heat shock proteins, and cytokines. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2017;3:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12011-017-1122-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luiken J.J., Willems J., Coort S.L., Coumans W.A., Bonen A., Van Der Vusse G.J. Effects of cAMP modulators on long-chain fatty-acid uptake and utilization by electrically stimulated rat cardiac myocytes. Biochem J. 2002;367:881–887. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen L., Pedersen L.M., Liaset B., Ma T., Petersen R.K., van den Berg S. cAMP-dependent signaling regulates the adipogenic effect of n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:7196–7205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707775200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahan K., Khan M., Singh I. Therapy for X-adrenoleukodystrophy: normalization of very long chain fatty acids and inhibition of induction of cytokines by cAMP. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:1091–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj S., Skiba G., Weremko D., Fandrejewski H., Migdał W., Borowiec F. The relationship between the chemical composition of the carcass and the fatty acid composition of intramuscular fat and backfat of several pig breeds slaughtered at different weights. Meat Sci. 2010;86:324–330. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartin J.L., Coleman E.S., Steele B. Interaction of cyclic AMP- and calcium-dependent mechanisms in the regulation of growth hormone-releasing hormone-stimulated growth hormone release from ovine pituitary cells. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 1996;13:229–238. doi: 10.1016/0739-7240(95)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenkovich C.F. Regulation of fatty acid synthase (FAS) Prog Lipid Res. 1997;36:43. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(97)00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin D. The effect of seamustard on blood lipid profiles and glucose level of rats fed diet with different energy composition. Nutr Res Pract. 2009;3:31–37. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2009.3.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sink J.D., Wilson L.L., Mccarthy R.D., Rugh M.C. Interrelationships between serum lipids, energy intake, milk production, growth and body characteristics in angus-holstein cows and their progeny. J Anim Sci. 1973;36:313–317. [Google Scholar]

- Smith S., Witkowski A., Joshi A.K. Structural and functional organization of the animal fatty acid synthase. Prog Lipid Res. 2003;42:289–317. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(02)00067-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan B., Yin Y., Liu Z., Li X., Xu H., Kong X. Dietary L-arginine supplementation increases muscle gain and reduces body fat mass in growing-finishing pigs. Amino Acids. 2009;37:169–175. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanghe S., Cox E., Melkebeek V., De Smet S., Millet S. Effect of fatty acid composition of the sow diet on the innate and adaptive immunity of the piglets after weaning. Vet J. 2014;200:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebbey P.W., Mcgowan K.M., Stephens J.M., Buttke T.M., Pekala P.H. Arachidonic acid down-regulates the insulin-dependent glucose transporter gene (GLUT4) in 3T3-L1 adipocytes by inhibiting transcription and enhancing mRNA turnover. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:639–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.J., Cui Y.Z., Zhang X.Y., Su J. Effect of early weaning on the expression of excitatory amino acid transporter 1 in the jejunum and ileum of piglets. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:6518–6525. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt M.J. Lipid metabolism in contracting muscle-HSL takes a back seat. J Physiol. 2013;591:4951. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.262766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Xie C.Y., Li B., Zhou H., Yao J., Li K. Effect of Yeast extract on growth performance and intestinal mucosa morphology of weanling piglets. J Anim Plant Sci. 2016;26:1568–1575. [Google Scholar]

- Yan X.C., Wang Y.Z., Zi-Rong X.U. Regulation of fatty acid synthase(FAS) gene expression in animals. Acta Zoonutrimenta Sinica. 2002;2:1–4. [Google Scholar]