Abstract

Background: A key concern among patients who undergo thyroid surgery is postoperative weight gain. Yet, the impact of thyroid surgery on weight is unclear.

Methods: The population-based Rochester Epidemiology Project was used to examine weight and body mass index (BMI) changes at one, two, and three years of follow-up in (i) patients with thyroid cancer and benign thyroid nodules after thyroid surgery, and (ii) patients with thyroid nodules who did not have surgery. A comprehensive systematic review of the published literature from inception to February 2016 was also conducted. The results were pooled across studies using a random effects model.

Results: A total of 435 patients were identified: 181 patients with thyroid cancer who underwent surgery (group A), 226 patients with benign thyroid nodules without surgery (group B), and 28 patients with benign thyroid nodules undergoing surgery (group C). Small changes in mean weight, BMI, and the number of patients whose weight increased between 5 and 10 kg were similar during each year of follow-up between patients in groups A and B. Furthermore, age >50 years, female sex, baseline BMI >25 kg/m2, and thyrotropin value at one to two years were not predictors of a 5% weight change. In the meta-analysis, 11 studies were included. One to two years after surgery for thyroid cancer or thyroid nodules, patients gained on average 0.94 kg [confidence interval (CI) 0.58–1.33] and 1.07 kg [CI 0.26–1.87], respectively. Patients with benign thyroid nodules who did not have surgery gained 1.50 kg [CI 0.60–2.4] at the longest follow-up.

Conclusions: On average, patients receiving care for thyroid nodules or cancer gain weight, but existing evidence suggests that surgery for these conditions does not contribute significantly to further weight gain. Clinicians and patients can use this information to discuss what to expect after thyroid surgery.

Keywords: : thyroid cancer, thyroid nodules, weight, TSH suppression

Introduction

Approximately 130,000 thyroid surgeries related to either cancer or nodules were conducted in the United States in 2011, a number that is increasing at a rate of 12% per year (1). The increase in surgical procedures may be a consequence of the increased detection of patients with thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer (2,3). Given the increasing numbers of patients undergoing thyroid surgery, it is critical to understand the possible adverse effects associated with this procedure, so that patients and clinicians can make informed decisions.

Patients with hyperthyroidism commonly experience weight gain after thyroidectomy. This occurs due to the reduction in circulating thyroid hormone, thus ameliorating the weight-lowering effects of elevated thyroid hormones (4,5). On the other hand, the effect of thyroid surgery on weight across euthyroid patients is unclear. Following thyroid surgery, patients often complain of weight gain, even when they have achieved biochemical euthyroidism. Studies examining this issue have found mixed results. Many of these studies have unclear/incomplete follow-up and are at high risk of selection bias (6–9). A population-based study can address some of these limitations. By analyzing a population within a geographic location, these studies are less prone to selection and referral bias than non-population-based studies (10). Population-based studies also facilitate longitudinal data collection, as they gather data from a variety of sources within a geographic region and are not limited to one source or healthcare system.

A population-based study was conducted to understand better the extent to which patients undergoing thyroid surgery for thyroid cancer or thyroid nodules experienced any weight change. In addition, a systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted of studies assessing weight change, which facilitated the interpretation of the results within the context of the body of evidence.

Methods

Population-based study

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the Mayo Foundation and Olmsted Medical Center. The Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) was used to identify residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, and grouped them into three cohorts: group A, patients with thyroid cancer (confirmed by histology) diagnosed between 2000 and 2012 treated with thyroid surgery; group B, patients with benign thyroid nodules diagnosed between 2003 and 2006 not treated with thyroid surgery; and group C, patients with benign thyroid nodules diagnosed between 2003 and 2006 treated with thyroid surgery. The rationale for different times in the cohorts was twofold: (i) for the thyroid cancer cohort, a wider inclusion period was needed in order to capture a larger sample, and (ii) the other two cohorts were already identified as part of a different published analysis, and its weight data was used in this report (11).

The REP medical records linkage system includes patients from all medical care facilities used by the residents of Olmstead County, Minnesota: the Mayo Clinic, the Olmsted Medical Center, and several private practices. The estimated population of Olmsted County in 2002 was 164,129 people. The REP allowed patients to be followed across the full spectrum of disease without relying on administrative data (12).

Reviewers extracted from each medical record: age, sex, date and type of thyroid surgery, and date of fine-needle aspiration (FNA) that served as the index date for those patients who did not undergo thyroid surgery. For patients with thyroid cancer, reviewers extracted whether radioactive iodine (RAI) treatment was given and the method of preparation (withdrawal vs. stimulation with recombinant human thyrotropin [rhTSH]).

The weight, serum thyrotropin (TSH), and free thyroxine (fT4) values available during the three months before and up to three years after surgery or FNA were extracted electronically. TSH values >10 IU/mL in patients with thyroid cancer undergoing follow-up were excluded, as these were most likely related to levothyroxine withdrawal. Patients with any of the following variables potentially associated with weight changes were excluded: weight reduction surgery, recent pregnancy, advanced heart disease, liver kidney disease, use of approved drugs for weight loss, or systemic steroid therapy.

Baseline values of weight and height were obtained from the evaluations usually performed up to 12 weeks prior to thyroidectomy. Patients were weighed wearing indoor clothes. Documented heights and weights were used to determine body mass index (BMI) calculated as weight in kilograms divided by square of height in meters. The baseline weights and BMIs were compared to data obtained at time point 1 (between >6 and 12 months post thyroidectomy or FNA), time point 2 (between >12–24 months post thyroidectomy or FNA), and time point 3 (between >24–36 months after thyroidectomy or FNA).

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were summarized according to variable type and distribution. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Wilcoxon's rank sum test for continuous variables. Simple logistic regression was conducted to evaluate the association between age >50 years, female sex, BMI >25 kg/m2, or TSH values at one to two years and weight change of >5% at one and two years of follow-up.

Systematic review and meta-analysis

This study was conducted following a systematic review protocol and is reported using current standards for the reporting of systematic reviews (13).

Eligibility criteria

Eligibility criteria were full publications of observational studies with: (i) patients with thyroid cancer or benign thyroid nodules treated with thyroid surgery and/or a comparison group not treated with thyroid surgery and (ii) measurement of weight and/or BMI before and after surgery/follow-up. The outcomes of interest were the mean difference in body weight and BMI before and after surgery.

Studies in which the required information to determine eligibility was not available in the manuscript and no response from the authors was obtained were excluded. Studies were included regardless of their publication status, language, or size. Review articles, commentaries, and letters that did not contain original data were excluded.

Study identification and selection

A comprehensive search of several databases starting at the inception of each database to February 2016 was conducted (see Supplementary Appendix S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/thy). The databases included Ovid Medline In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, Ovid Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Ovid Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Scopus. The search strategy was designed and conducted by an experienced librarian, with input from the study's principle investigator. Controlled vocabulary supplemented with keywords was used to search for studies evaluating selected outcomes in patients with thyroid cancer or benign thyroid nodules. Experts in the field were consulted to identify studies missed by the search strategy.

The search results were uploaded into systematic review software (DistillerSR, Ottawa, Canada). Reviewers working independently and in duplicate reviewed all abstracts and titles for inclusion (κ statistic = 0.85). After abstract screening and retrieval of potentially eligible studies, the full-text publications were assessed for eligibility. Disagreements were resolved by consensus (the two reviewers discussed the discrepancy and reached a decision).

Data collection and management

Working independently and in duplicate and using a standardized form, reviewers collected the following information from each included study: study design, patient age and sex, sample size, type of thyroid surgery, weight and BMI values before and after surgery, follow-up time, whether patients with thyroid cancer received RAI and preparation method (TSHr or withdrawal), thyroid function tests values, and exclusion criteria for each study.

Risk of bias assessment

The methodological quality of the included observational studies was assessed using a modified Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, independently and in duplicate by trained reviewers (14). This instrument assesses the protection against bias by evaluating how the investigators evaluated outcomes and ensured the comparability of study groups.

Author contact

To reduce reporting bias, the corresponding author (or any other author if it was not possible to contact the corresponding author) of each eligible study was contacted by e-mail when clarification or more information was needed to determine eligibility or to complete analyses. Three authors were contacted for clarification and to obtain further data; one replied (9).

Meta-analysis

A random-effects meta-analysis was conducted using the DerSimonian–Laird random effects method to pool mean differences for continuous outcomes and their associated confidence intervals (CI) (15). Heterogeneity was assessed by I2 (16). All the analyses were performed using RevMan 5.2 software (Copenhagen RmRCPV, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014).

Subgroups and sensitivity analyses

The difference in effect sizes were evaluated between subgroups based on: time of follow-up, TSH values, sex, age, and administration of iodine treatment in patients with thyroid cancer.

Results

Population-based study

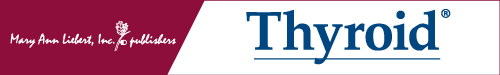

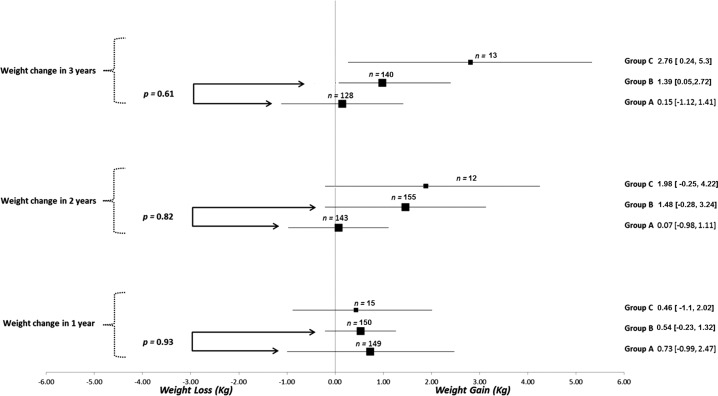

A total of 435 patients were identified: 181 patients with thyroid cancer who underwent surgery (group A), 226 patients with benign thyroid nodules without surgery (group B), and 28 patients with benign thyroid nodules undergoing surgery (group C). Overall, the majority of the patients were overweight, middle aged, and female (Table 1). In the thyroid cancer cohort (group A), 83% of the patients underwent total thyroidectomy, and in the benign nodule group (group B), 25% of the patients underwent total thyroidectomy. In patients with benign thyroid disease, the presence of compressive symptoms was the most common indication for surgery (47%), followed by concern for cancer due to size or other clinical features (21%). Most of the patients in the thyroid cancer cohort had low-risk thyroid cancer (64%).RAI treatment was received by 30% of the patients, and all were prepared with thyroid hormone withdrawal. None of the patients received therapy with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Mean weight and BMI differences between baseline and each of the follow-up times were not different between patients in group A and those in group B. Comparison with group C was considered not appropriate, given that the small sample size of this group, which would have led to unreliable p-value estimate of effects (Figs. 1 and 2). Overall, the number of patients whose weight increased between 5 and 10 kg increased during each year of follow-up in each group. In fact, 16% of the patients gained between 5 and 10 kg at three years of follow-up (Supplementary Table S1). Univariate analysis did not identify any predictors of weight change (age >50 years, female sex, baseline BMI >25 kg/m2, or TSH value at one to two years; Supplementary Table S2).

Table 1.

Clinical Features and Mean Weight, BMI, and TSH According to the Diagnosis and Treatment Group

| Group A | Group B | Group C | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | (Thyroid cancer and surgery) | (Benign nodule without surgery) | (Benign nodule and surgery) | |||||

| n = 435 | n = 181 | n = 226 | n = 28 | |||||

| Clinical features | ||||||||

| Mean age, years | 50 | (15.91) | 47 | (14.68) | 53 | (16.13) | 44 | (16.32) |

| Female patients, % | 75 | 69 | 80 | 79 | ||||

| Weight | ||||||||

| Mean weight baseline, kg | 79 | (19.49) | 82 | (19.02) | 77 | (20.06) | 78 | (17.95) |

| Mean weight at year 1, kg | 80 | (21.07) | 82 | (21.37) | 79 | (21.26) | 73 | (12.17) |

| Mean weight at year 2, kg | 81 | (22.50) | 82 | (20.25) | 80 | (24.72) | 71 | (14.16) |

| Mean weight at year 3, kg | 81 | (22.13) | 82 | (21.1) | 81 | (23.57) | 73 | (12.94) |

| BMI | ||||||||

| Mean BMI baseline, kg/m2 | 28 | (6.07) | 29 | (5.96) | 27 | (6.19) | 27 | (6.18) |

| Mean BMI at year 1, kg/m2 | 28 | (6.57) | 29 | (6.35) | 28 | (6.87) | 27 | (5.50) |

| Mean BMI at year 2, kg/m2 | 29 | (7.31) | 29 | (6.79) | 29 | (7.83) | 27 | (6.26) |

| Mean BMI at year 3, kg/m2 | 29 | (7.73) | 29 | (6.7) | 29 | (8.65) | 27 | (6.15) |

| TSHa | ||||||||

| Mean TSH at 7–12 months, IU/mL | 2.5 | (2.12) | 1.9 | (1.50) | 1.6 | (1.25) | ||

| Mean TSH year at 13–24 months, IU/mL | 1.6 | (1.86) | 4.8 | (14.24) | 5.6 | (12.71) | ||

| Mean TSH year at 25–36 months, IU/mL | 1.3 | (1.93) | 1.9 | (1.53) | 3.8 | (5.75) | ||

Data presented as mean (standard deviation).

TSH >10 IU/mL excluded for group A (two cases, 7–12 months; 45 cases, 12–24 months; 11 cases, 24–36 months).

BMI, body mass index; TSH, thyrotropin.

FIG. 1.

Mean differences in weight according to group at one to three years of follow up. Data presented as estimate in kg (confidence interval [CI]) for mean difference in weight within each group at one to three years of follow-up.

FIG. 2.

Mean differences in body mass index (BMI) according to group at one to three years of follow-up time. Data presented as estimate in kg (CI) for mean difference in BMI within each group at one to three years of follow-up.

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis

In patients with low-risk thyroid cancer who underwent total thyroidectomy, the expected change in weight and BMI at one to three years of follow-up was minimal (Supplementary Table S3). Similarly, patients with thyroid cancer who underwent total thyroidectomy had small positive estimates of weight gain, and those who underwent lobectomy had small estimates of weight loss. However, there was no difference between the groups (Supplementary Table S4). In the thyroid cancer cohort, patients with TSH values <0.4 mIU/L at any time frame were excluded, and again small estimates for weight change were found (Supplementary Table S5).

Systematic review and meta-analysis

Study identification

A total of 745 studies were identified through the search, of which 10 met the inclusion criteria, including the population-based analysis. Thus, 11 studies were included (6–9,17–22). The complete study selection process is described in Supplementary Figure S1, and a summary of the included studies is found in Table 2. Studies included mostly middle-aged women. Patients with thyroid cancer were treated with the goal of suppressing their TSH values in comparison to patients with benign disease for whom no specific target was described.

Table 2.

Studies Included in the Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

| Patients with benign nodules undergoing follow-up | Patients with benign nodules undergoing surgery | Patients with thyroid cancer after surgery | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Year | Country | n | % Female | Age, years (SD) | TSH | Follow-up time | n | % Female | Age, years (SD) | TSH | Follow-up time | n | % Female | Age, years (SD) | TSH | Follow-up time |

| Kormas, 1998 (7) | Australia | 8 | 100 | 57 (7) | Normal | 1 year | ||||||||||

| Tigas, 2000 (21) | Scotland | 25 | 72 | 43 | S | 12 ± 0.6 months | ||||||||||

| Mazokopakis, 2006 (18) | Greece | 26 | 100 | 39 | S | 4 years | ||||||||||

| Jonklaas, 2011 (6) | United States | 120 | 75 | 48 (12) | Normal | 1 year | 120 | 75 | 46 | 1 year | ||||||

| Weinreb, 2011 (22) | United States | 92 | 76 | 50.4 (1.5) | Normal | 7.6 years | 102 | 66 | 45.8 | S | 8.3 years | |||||

| Polotsky, 2012 (19) | United States | 153 | 72 | 43 | S | 1–2 years; 3–5 years | ||||||||||

| Rotondi, 2014 (9) | Italy | 118 | 81 | 51.4 (11.6) | Normal | 40–60 days, 90 days | 41 | 70 | 48.5 (16) | S | 40–60 days, 90 days | |||||

| Sohn, 2015 (20) | Korea | 350 | 83 | 50.1 | Normal | 1–2 years, 3–4 years | 700 | 83 | 50.1 | S | 1–2 years, 3–4 years | |||||

| Kedia, 2016 (17) | United States | 144 | 80 | 49.9 | S | 1–3 years | ||||||||||

| Lang, 2016 (8) | China | 179 | 83 | 54.1 | Normal | 6–12 months | 898 | 84 | 52.1 | Normal | 6–12 months | |||||

| Singh Ospina (present study) | United States | 226 | 80 | 53 | Normal | 1–3 years | 28 | 79 | 44 | Variable | 1–3 years | 181 | 69 | 47 | Lower end of normal | 1–3 years |

S, suppressed.

Risk of bias assessment

Overall, the included studies were at a moderate risk of bias based on the domains of adequate follow-up and adjustment for confounders. A summary of the risk of bias assessment of each study is found in Supplementary Table S6.

Meta-analysis

Patients with thyroid cancer who underwent surgery (group A)

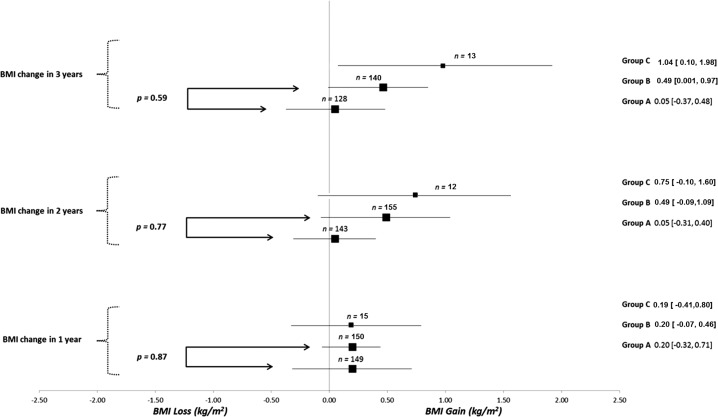

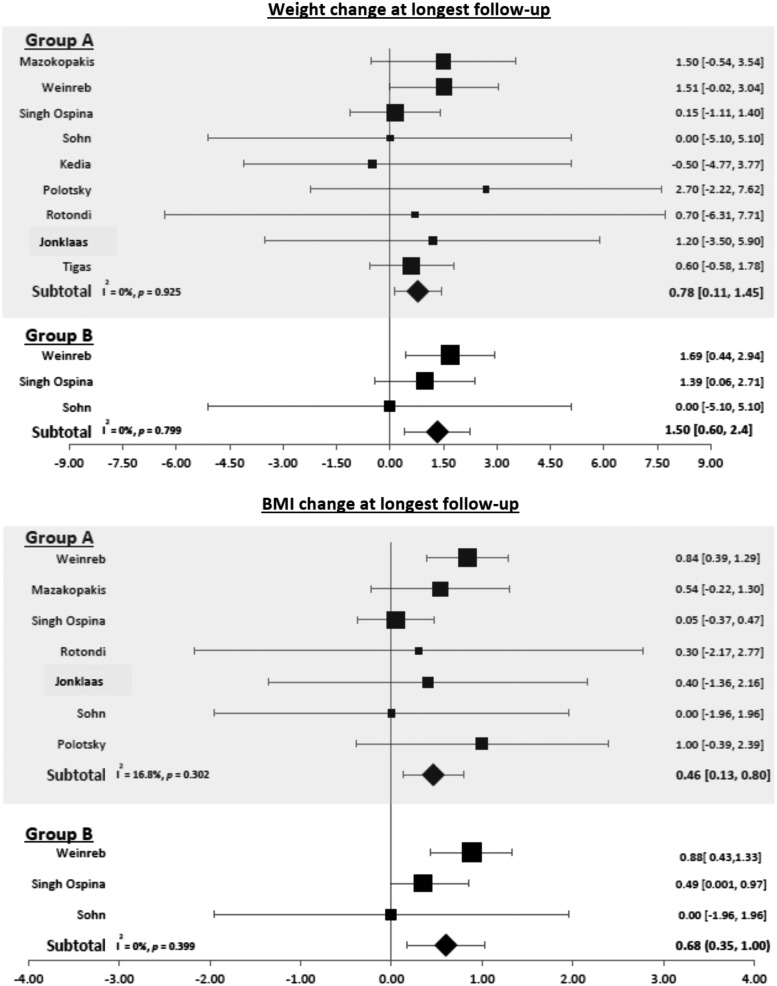

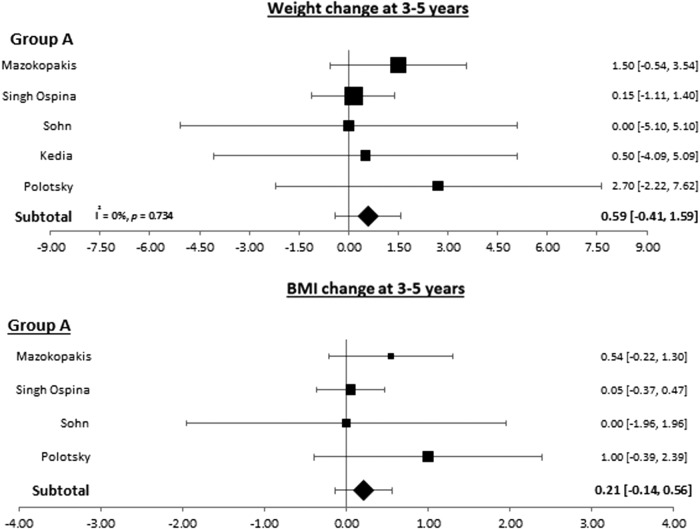

Patients with thyroid cancer who underwent surgery when using the longest follow-up provided gained 0.78 kg [CI 0.11–1.45] and had a 0.46-unit increase in their BMI ([CI 0.13–0.80]; Fig. 3). This weight gain remained statistically significant at one to two years of follow-up (0.94 kg [CI 0.58–1.33]) but not at three to five years of follow-up (0.59; [CI −0.41 to 1.59]; Figs. 4 and 5).

FIG. 3.

Forest plots depicting weight and BMI changes at longest follow-up observed in group A (patients with thyroid cancer who underwent surgery) and group B (patients with benign thyroid nodules without surgery).

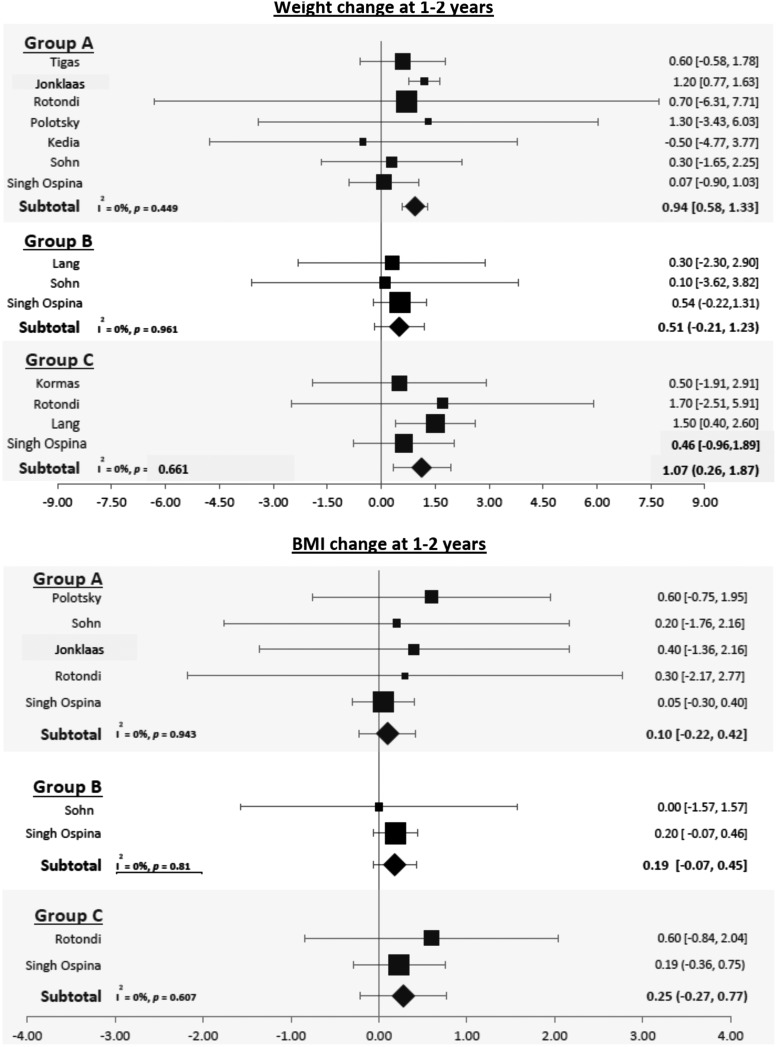

FIG. 4.

Forest plots depicting weight and BMI changes at one to two years observed in group A (patients with thyroid cancer who underwent surgery), group B (patients with benign thyroid nodules without surgery), and group C (patients with benign thyroid nodules undergoing surgery).

FIG. 5.

Forest plots depicting weight and BMI changes at three to five years observed in group A (patients with thyroid cancer who underwent surgery).

Patients with benign nodules without surgery (group B)

At longest follow-up, patients with benign nodules gained 1.50 kg [CI 0.6–2.4] and had an increase in BMI of 0.68 kg/m2 ([CI 0.35–1.00]; Fig. 3). Weight increased by 0.51 kg [CI −0.21 to 1.23) at one to two years and BMI by 0.19 kg/m2 [CI −0.07 to 0.45], but these changes were not statistically significant (Fig. 4).

Patients with benign nodules who underwent surgery (group C)

Patients with benign nodules who underwent surgery gained 1.07 kg [CI 0.26–1.87] at one to two years of follow-up (Fig. 4).

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis

A subgroup analysis was performed of the available studies by evaluating weight and BMI changes at different follow-up times. It was not possible to perform any of the other preplanned analyses due to inconsistent reporting of the data in the original studies.

Discussion

No clinically significant increase in weight or BMI was found between patients with benign nodules who did not have surgery and patients with thyroid cancer who underwent thyroidectomy. A modest increase in weight was noted in the group of patients with benign thyroid nodules who underwent surgery. However, the sample size was small. A consistent increase was noted in the number of patients with a weight gain of >5–10 kg during follow-up in every group. A subgroup and sensitivity analysis of the thyroid cohort (surgery type, thyroid cancer risk, TSH levels) failed to reveal a clinically significant mean weight change in this population. Therefore, the results suggest that any weight change in patients after thyroid surgery may be attributed to other factors, for instance age. The latter is further supported by findings of several large population-based studies of healthy individuals. These studies support the notion that weight gain is expected with aging: 0.23 kg/year (National Health Examination Follow-Up Study), 0.1–0.25 kg/year (Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study), and 0.25–0.34 kg/year (Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging) (23–25). The results of the systematic review and meta-analysis further confirm this conclusion, with modest increases in weight noted in each group at different time intervals.

It was not possible to find a clear predictor of weight gain. A few of the included studies in the meta-analysis assessed the role of several variables on the impact of thyroid surgery on weight (e.g., TSH level at baseline, age, sex) without consistent effect (8), except for the impact of thyroid hormone withdrawal before RAI (20). The latter could be due to the increase in fat content and decrease in basal energy expenditure in patients experiencing short yet significant hypothyroidism. The magnitude of weight gain reported in this subgroup of patients is mild. Many have also argued that weight gain after thyroidectomy may be due triiodothyronine (T3) deficiency, and this deficiency and weight gain effect is masked in patients with thyroid cancer due to suppressive therapy with levothyroxine (20). However, normal T3 levels and normal TSH levels are frequently achieved with levothyroxine treatment (6). The mean TSH in the present thyroid cancer population after thyroidectomy was within normal limits, as the majority of thyroid cancer cases were low risk for recurrence and mortality, and no significant weight gain was observed in this group.

The present analysis has strengths and limitations. A population-based study was performed that allowed the risk of referral bias to be reduced when evaluating weight changes in patients with benign and malignant nodular thyroid disease. However, due to the observational nature of the study, it was not possible to control for unknown confounders and known confounders not recorded during routine clinical practice (e.g., caloric intake, physical activity, or overall health status). In the thyroid cancer cohort, TSH values >10 IU/mL were arbitrarily excluded under the assumption that this represented thyroid hormone withdrawal. This exclusion may affect the estimates of TSH values. Some of the estimates have large standard deviations, which could be related to small size during follow-up. Furthermore, the retrospective nature of data collection in this study decreases the confidence that weight was ascertained properly. However, weight measures during routine clinical practice are highly correlated with weights obtained by research and clinical measures (26,27). An important strength of the analysis is that the results of the population-based study were evaluated in the context of the available body of evidence about weight changes after thyroidectomy by conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis of the available literature. This process also facilitates an assessment of the quality of the evidence of the included studies, including the current study, which in view of the intrinsic limitations of observational data is considered low.

Conclusions

Low-quality evidence suggests no clinically significant impact of thyroid surgery for thyroid cancer or nodules on a patient's weight. Weight, however, did increase among all groups during follow-up. Although the cause of weight gain is unclear, it is likely due to factors unrelated to the intervention. Clinicians and patients are encouraged to use this information to discuss what to expect after thyroid surgery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J.P.B. is supported by the Karl-Erivan Haub Family Career Development Award in Cancer Research at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, honoring Richard F. Emslander, MD.

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Sosa JA, Hanna JW, Robinson KA, Lanman RB. 2013. Increases in thyroid nodule fine-needle aspirations, operations, and diagnoses of thyroid cancer in the United States. Surgery 154:1420–1426; discussion 1426–1427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh Ospina N, Maraka S, Espinosa De Ycaza AE, Ahn HS, Castro MR, Morris JC, Montori VM, Brito JP. 2016. Physical exam in asymptomatic people drivers the detection of thyroid nodules undergoing ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration biopsy. Endocrine 54:433–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaccarella S, Franceschi S, Bray F, Wild CP, Plummer M, Dal Maso L. 2016. Worldwide thyroid-cancer epidemic? The increasing impact of overdiagnosis. N Engl J Med 375:614–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dale J, Daykin J, Holder R, Sheppard MC, Franklyn JA. 2001. Weight gain following treatment of hyperthyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 55:233–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mullur R, Liu YY, Brent GA. 2014. Thyroid hormone regulation of metabolism. Physiol Rev 94:355–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jonklaas J, Nsouli-Maktabi H. 2011. Weight changes in euthyroid patients undergoing thyroidectomy. Thyroid 21:1343–1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kormas N, Diamond T, O'Sullivan A, Smerdely P. 1998. Body mass and body composition after total thyroidectomy for benign goiters. Thyroid 8:773–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lang BH, Zhi H, Cowling BJ. 2016. Assessing perioperative body weight changes in patients thyroidectomized for a benign nontoxic nodular goitre. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 84:882–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rotondi M, Croce L, Pallavicini C, Manna LL, Accornero SM, Fonte R, Magri F, Chiovato L. 2014. Body weight changes in a large cohort of patients subjected to thyroidectomy for a wide spectrum of thyroid diseases. Endocr Pract 20:1151–1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Booth CM, Tannock IF. 2014. Randomised controlled trials and population-based observational research: partners in the evolution of medical evidence. Br J Cancer 110:551–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh Ospina N, Maraka S, Espinosa de Ycaza AE, Brito JP, Castro MR, Morris JC, Montori VM. 2016. Prognosis of patients with benign thyroid nodules: a population-based study. Endocrine 54:148–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Pankratz JJ, Brue SM, Rocca WA. 2012. Data resource profile: the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical records-linkage system. Int J Epidemiol 41:1614–1624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 62:1006–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wells G SB, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. 2013. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Available at: www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed February1, 2017)

- 15.DerSimonian R, Laird N. 1986. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7:177–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. 2003. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327:557–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kedia R, Lowes A, Gillis S, Markert R, Koroscil T. 2016. Iatrogenic subclinical hyperthyroidism does not promote weight loss. South Med J 109:97–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazokopakis EE, Starakis IK, Papadomanolaki MG, Batistakis AG, Papadakis JA. 2006. Changes of bone mineral density in pre-menopausal women with differentiated thyroid cancer receiving L-thyroxine suppressive therapy. Curr Med Res Opin 22:1369–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polotsky HN, Brokhin M, Omry G, Polotsky AJ, Tuttle RM. 2012. Iatrogenic hyperthyroidism does not promote weight loss or prevent ageing-related increases in body mass in thyroid cancer survivors. Clin Endocrinol 76:582–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sohn SY, Joung JY, Cho YY, Park SM, Jin SM, Chung JH, Kim SW. 2015. Weight changes in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma during postoperative long-term follow-up under thyroid stimulating hormone suppression. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 30:343–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tigas S, Idiculla J, Beckett G, Toft A. 2000. Is excessive weight gain after ablative treatment of hyperthyroidism due to inadequate thyroid hormone therapy? Thyroid 10:1107–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinreb JT, Yang Y, Braunstein GD. 2011. Do patients gain weight after thyroidectomy for thyroid cancer? Thyroid 21:1339–1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheehan TJ, DuBrava S, DeChello LM, Fang Z. 2003. Rates of weight change for black and white Americans over a twenty year period. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 27:498–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimokata H, Andres R, Coon PJ, Elahi D, Muller DC, Tobin JD. 1989. Studies in the distribution of body fat. II. Longitudinal effects of change in weight. Int J Obes 13:455–464 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Wye G, Dubin JA, Blair SN, Di Pietro L. 2007. Weight cycling and 6-year weight change in healthy adults: The Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 15:731–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arterburn D, Ichikawa L, Ludman EJ, Operskalski B, Linde JA, Anderson E, Rohde P, Jeffery RW, Simon GE. 2008. Validity of clinical body weight measures as substitutes for missing data in a randomized trial. Obes Res Clin Pract 2:277–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiMaria-Ghalili RA. 2006. Medical record versus researcher measures of height and weight. Biol Res Nurs 8:15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.