Abstract

Background/Aim: This study aimed to examine the effects of nutritional intervention on the prognosis of patients with cardiopulmonary failure undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) therapy in Taiwan. Materials and Methods: An institutional review board-approved retrospective study was conducted on patients receiving ECMO therapy in the intensive care unit of the China Medical University Hospital, Taiwan, from January 2013 to December 2013. The study included 102 patients with cardiopulmonary failure receiving ECMO therapy. Results: The data indicated that higher survival rates were closely related to lower age and APACHE II scores among the patients. In addition, compared to patients who deceased, those who survived had a higher total calorie intake. Most patients could tolerate bolus feeding and polymeric formulas. Furthermore, patients who underwent nutritional therapy with nutritional goals greater than 80% achieved a better outcome and lower mortality than other patients. Conclusion: Early nutritional intervention could benefit patients undergoing ECMO, and those who reached the delivery goal of 80% had significantly better outcomes than other patients. Enteral feeding can begin early and was well tolerated by patients receiving ECMO therapy. Following individual nutrition goals is critical for better outcomes, and this analysis might be useful in establishing individualized nutrition goals for oriental population when caring for critically ill patients.

Keywords: Cardiopulmonary failure patients, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy, nutritional intervention

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) therapy is administered to critically ill patients following a cardiopulmonary bypass, cardiac surgery, or severe respiratory failure. ECMO can be divided into veno-arterial (VA) and veno-venous (VV) types. The VA type is employed for both cardiac and pulmonary support, such as acute cardiac failure or failure to wean from a cardiopulmonary bypass following cardiac surgery, whereas the VV type is used for reversible respiratory failure with normal cardiac function (1). ECMO can cause hemodynamic alteration, decreased microcirculation, and therefore reduced gut perfusion (2). Furthermore, it may activate systemic inflammation, causing gut barrier dysfunction and bacterial translocation (3), leading to further difficulties in enteral nutrition (EN).

Malnutrition is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients (4), and patients may not be able to tolerate EN (5). Early EN during a critical illness is suggested and provides an improved clinical outcome (6), with the majority of international practice guidelines recommending it (7). Early EN in critically ill patients is important to not only improve patient survival, but also reduce hospital costs (8). Ferrie et al. revealed that EN was well tolerated by patients who were receiving ECMO, whether through VV or VA mode (9). Their data suggested that ECMO should not exclude patients from receiving the well-documented benefits of early EN during critical illnesses (9). Early EN is associated with reduced mortality in critically ill patients receiving mechanical ventilation who are in an unstable hemodynamic condition, as indicated by the use of vasopressors (10). EN initiated within the first 24 hours of ECMO support appears to be safe and well tolerated in adult patients. Patients who met the calorie goals in the earlier stages had lower mortality rates and no observed adverse reactions (11). In contrast with the above-mentioned study, Lukas et al. performed an investigation in the early period of ECMO support, delivering 18% of total nutritional requirements by day 2, 30% by day 3, and 55% over the entire period of ECMO support (12). The investigation demonstrated that survivors did not achieve better nutritional adequacy than nonsurvivors.

The use of ECMO is becoming increasingly prevalent in Taiwan, demonstrating a survival rate of approximately 47.7% (13). However, no study has focused on the relationship between nutritional therapy and the clinical outcomes of ECMO use in the oriental population. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of nutritional therapy on prognosis and expect to establish a standard practice for the treatment of patients undergoing ECMO.

Materials and Methods

Patient collection and study design. A retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed as having cardiopulmonary failure and receiving ECMO in the intensive care unit (ICU) of China Medical University Hospital, Taiwan was conducted. Between January 2013 and December 2013, 102 patients were supported with ECMO after cardiac failure. Patients supported with ECMO ranged in age form 19 to 94 years (mean, 55.4±17.4), and 70 (68%) were male. The study protocol was approved by the China Medical University Hospital Research Ethics Committee of human trials (CHUH104-REC3-027). Nutritional therapy was provided during the study period in a protocol-listed fashion and executed and audited by a physician-in-charge as well as a registered dietitian.

All patients in the study received nutritional therapy according to the unit’s standard protocols, with the aim to begin nutritional therapy through a nasogastric tube within 24 hours of the patient being admitted to the ICU. EN products are usually administered through bolus feeding of a standard isocaloric polymeric formula, based on clinical requirements and the appropriate choice by the dietitian. The delivery protocol was adjusted to administer continuous feeding if the patient was unable to tolerate bolus feeding. The patients were divided into two groups: a survival group and a deceased group. Daily energy requirements were calculated by a dietitian using the Harris-Benedict equation (14) and by applying an activity factor (1.2) and stress factor (1.2-1.5). The basal metabolic rate (BMR) was calculated for both men and women. The calculation for men (metric) is outlined as follows:

BMR=66.47 + (13.75 × weight in kg) + (5.003 × height in cm) - (6.755 × age in years); and the calculation for women (metric) is outlined as follows:

BMR=655.1 + (9.563 × weight in kg) + (1.850 × height in cm) - (4.676 × age in years).

The method used in clinical practice to determine energy requirements in all patients was also applied in our ICU. Daily protein requirements were estimated to be at least 1.2 g/kg body weight based on the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism guidelines (2006) (15). Protein conservation therapy of 0.6-1 g/kg body weight/day and extracorporeal therapy of 1.0-1.5 g/kg body weight/day were administered (15). Data were collected on each patient’s nutritional intake, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II), ICU stay (days), hospital stay (days), biochemical information, and complications.

Statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was performed to assess the descriptive measures used to analyze the data, which are expressed as a mean±standard deviation (SD). The student t-test was employed to compare groups with respect to continuous variables. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS 2007.

Results

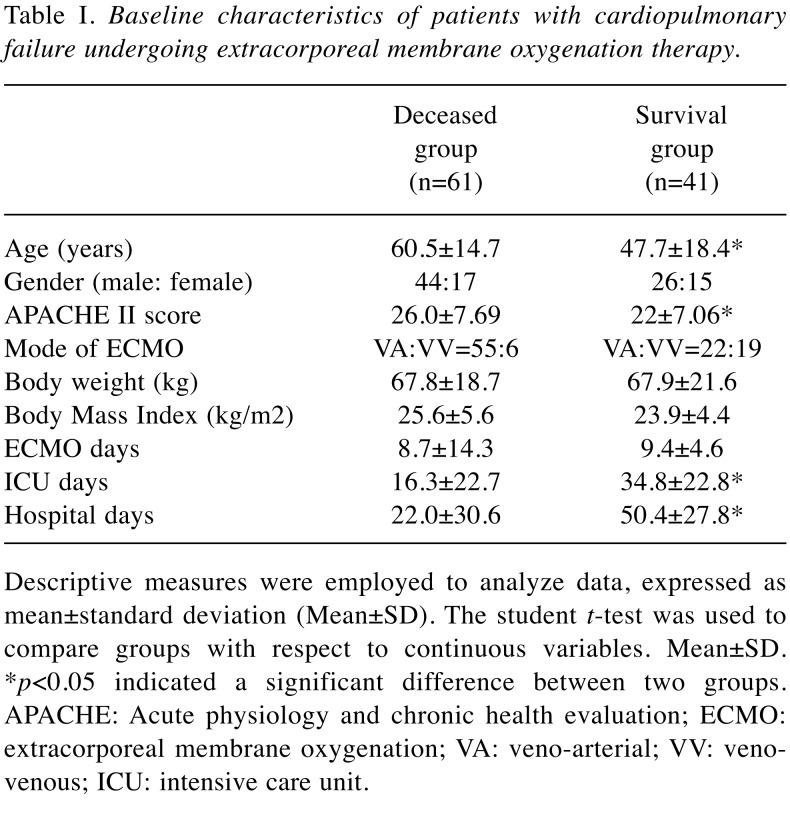

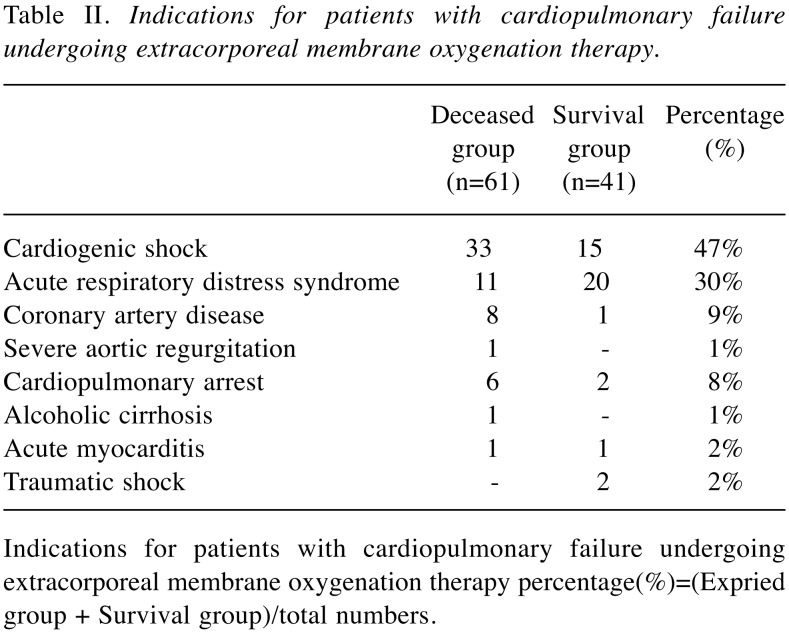

In this study, 102 patients were included, of whom 77 required VA ECMO for cardiac and respiratory indications and 25 received VV ECMO for respiratory indications. The patient demographics are shown in Table I. A total of 61 patients deceased and 41 survived. Thus, the patients were divided into two groups, deceased (44 men, 17 women; median age, 60.5 years; VA:VV=55:6) and survival (26 men, 15 women; median age, 47.7 years; VA:VV=22:19) for further analysis. APACHE II is a severity-of-disease classification system for patients in an ICU. Higher scores correspond to a more severe disease and a higher risk of death. The APACHE II score was significantly lower in the survival group (22±7.06) than in the deceased group (26±7.69) (p<0.05). The body mass index (BMI) (p=0.28) and ECMO days (p=0.37) of patients did not significantly differ between the two groups. However, the observed ICU stay and hospital stay (days) were longer in the survival group than in the deceased group (p<0.05). The indications of patients with ECMO therapy are presented in Table II, involving 47% cardiogenic shock and 31% acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), respectively.

Table I. Baseline characteristics of patients with cardiopulmonary failure undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy .

Descriptive measures were employed to analyze data, expressed asmean±standard deviation (Mean±SD). The student t-test was used tocompare groups with respect to continuous variables. Mean±SD.*p<0.05 indicated a significant difference between two groups.APACHE: Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation; ECMO:extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; VA: veno-arterial; VV: venovenous;ICU: intensive care unit.

Table II. Indications for patients with cardiopulmonary failure undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy.

Indications for patients with cardiopulmonary failure undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy percentage(%)=(Expried group + Survival group)/total numbers.

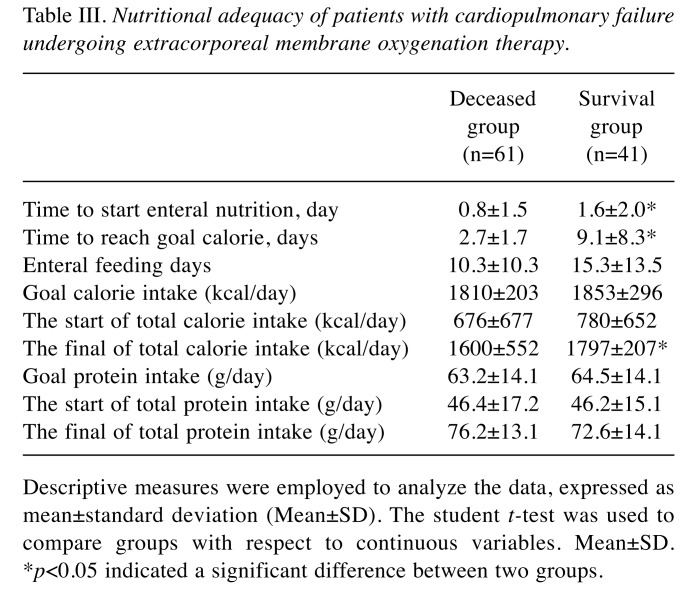

The nutritional assessments of the dietitian for target calories and proteins of patients were approximately 1832 kcal/day and 64 g/day, respectively, on average. The patients’ nutritional therapy is shown in Table III. All patients (including deceased and survival groups) reached the nutritional goal of calories per day after approximately 7.2 days (7.2±7.6 days). The initiation of EN calorie, protein, and feeding days did not significantly differ between the two groups. However, the final of total calories intake was higher in the survival group than in the deceased group (p=0.037). In the survival group, the total calories reached approximately 97% of the target calorific goal (Table III). We further observed that 80% of patients could tolerate the NG tube feeding diet. Moreover, 73% of survival patients could tolerate bolus feeding, and 27% required continuous feeding. Additionally, 78% of the survival group could tolerate the isocaloric polymeric formula, and 22% were administered a semi-elemental or elemental diet. An attempt was made to determine whether the hematological and biochemical parameters differed between the two groups. The white blood cell, platelet count, lactate, cholesterol, triglyceride, and pre-albumin data for these indices exhibited no significant difference between two groups (data not shown). This study demonstrated that complications may significantly affect the prognosis of patients. The complication rates of the two groups were also analyzed and compared. The complication rate was 26% in the deceased group, much higher than the 2.4% for the survival group. The most common complication was multiple organ failure.

Table III. Nutritional adequacy of patients with cardiopulmonary failure undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy.

Descriptive measures were employed to analyze the data, expressed asmean±standard deviation (Mean±SD). The student t-test was used tocompare groups with respect to continuous variables. Mean±SD.*p<0.05 indicated a significant difference between two groups.

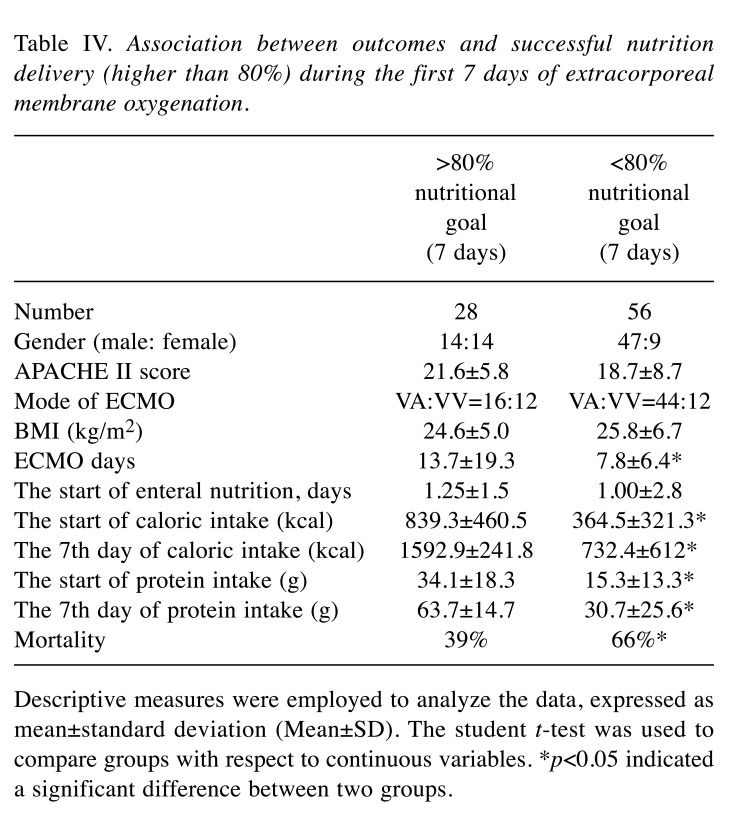

An attempt was also made to determine whether reaching the nutritional goal set at 80% during the first 7 days was associated with the treatment outcome. Table IV indicates that the ICU stay and hospital stay were longer for those patients during the first 7 days with more than an 80% nutritional goal than those patients with less than an 80% nutritional goal (p<0.01). In particular, improved nutrition delivery was strongly associated with lower mortality rate (p=0.01). For patients during the first 7 days who reached a higher nutritional goal (higher than 80%), the outcome and mortality rate were lower.

Table IV. Association between outcomes and successful nutrition delivery (higher than 80%) during the first 7 days of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Descriptive measures were employed to analyze the data, expressed asmean±standard deviation (Mean±SD). The student t-test was used tocompare groups with respect to continuous variables. *p<0.05 indicateda significant difference between two groups.

Discussion

In our hospital, 102 patients received ECMO therapy during the 1-year period analyzed in this retrospective study. The survival rate was 40% for the patients receiving ECMO in our hospital. Elsharkawy’s study demonstrated that the in-hospital survival rate of patients with VA ECMO varied from 30% to 50%, according to the cause of the corresponding cardiac dysfunction (16). Among the patients for adult postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock in another study, 54% survived to hospital discharge, whereas 47% required reoperation due to bleeding (17). Moreover, Allen et al. revealed that the use of ECMO in critically ill patients placed on extracorporeal life support for postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock (PCCS) resulted in a survival rate of 19%-67% (18). Smedira et al. reported that in a clinical experience of adults receiving ECMO for cardiac failure, survival rates at 24, 48, and 72 hours after the initiation of ECMO were 90%, 83%, and 76%, respectively. After 1 week, 2 weeks, and 30 days, the survival rates had decreased to 58%, 45%, and 38%, respectively. By 90 days, 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years, the survival rates were 33%, 29%, 26%, and 24%, respectively. Survival after being bridged from ECMO to an Left ventricular assist Derice (LVAD) or directly to transplantation was 85%,67% 54%, and 44% at 7 days, 30 days, 1 year, and 5 years, respectively, after cessation of ECMO (19). The above results indicated the high mortality of patients with ECMO and need to be addressed.

Among critically ill adults receiving ECMO in an Australian population, the survival rate for respiratory indications was 87% and that for cardiac indications was 50% (20). A study in Taiwan showed that 64.2% of patients were weaned off ECMO or bridged to ventricular assist devices and 32.1% of patients survived to discharge (21). Chiu et al. reported that younger patients who required a shorter duration of mechanical ventilation and had lower organ dysfunction scores before ECMO initiation achieved more favorable survival outcomes; the hospital survival rate in the study was 47.7% (13), which is consistent with the results of our study (40%) and the overall survival rate in Taiwan. Furthermore, in the current study, our results also revealed that the average age for the survival group (47.7 years) was much lower than that for the deceased group (60.5 years) (p<0.05) (Table I), supporting the argument that age may be among the most critical factors influencing the survival rate of patients undergoing ECMO. Furthermore, regarding the gender factor, our results indicated that male patients required ECMO more often than female patients, and gender might be associated with the incidence of cardiovascular disease (22). None of the previous investigations focused on the effect of nutritional intervention and the outcome of ECMO therapy in the oriental population, and in our study age and disease severity affected survival rates. In the analysis of disease severity, the deceased group had a higher APACHE II score than the survival group (Table I). Chung et al. reported that the APACHE II score was a strong independent predictor of an unfavorable in-hospital outcome (23), and the results from our study support their hypothesis that a high APACHE II score is correlated with a higher mortality rate. Regarding BMI, no significant difference was found between the two groups. In the current study, patients undergoing ECMO tended to be overweight; similarly, another study indicated that body weight was higher in patients undergoing ECMO (19). Being overweight or obese is known to be associated with cardiovascular disease, and our analysis indicated similar findings.

Bakhtiary et al. revealed that the average duration of ECMO was 6.4±4.5 days (24). In our current study, the average duration of ECMO use was 9 days (9.4±4.6 days) in survival group, and the days of ICU and hospital stay for the survival group were longer than those for the deceased group. This can be reasonably explained by the fact that the deceased group had a shorter length of stay and ICU days due to death. The indications for ECMO-supported patients’ primary diagnosis were heart failure and ARDS, with our analysis indicating similar diagnoses to other studies (10). In this study, about 75% of the participants were diagnosed with cardiogenic shock or ARDS, five cases were diagnosed with both cardiogenic shock and ARDS.

EN is possible and safe for patients with severe hemodynamic failure receiving VA ECMO (25). For nutritional intervention, the average stated feeding time of survival group was 1.6 days in this study. Scott et al. reported that the initiation of EN feeding within the first 24 hours of instituting VV ECMO in patients with severe respiratory failure was safe and well tolerated (26). Ferrie et al. indicated that the average stated feeding time was 13 hours in patients undergoing ECMO (9). These studies and our study are consistent in revealing that early enteral feeding in ECMO patients is safe without severe adverse effects. The deceased group achieved approximately 88% of the calorie goal, and the survival group reached 96.9% (Table III). The protein requirement could also reach a nutritional level above 100% in both groups (Table III). Furthermore, a total nutrition intake up to 80% of the nutritional goal resulted in low mortality rates (Table IV). Ferrie et al. also reported several models of significant associations between outcomes and successful nutrition delivery of ECMO in patients (9). Our design minimized the incomplete data bias that may occur with a retrospective study. However, our pilot trial in searching for a standardized protocol for the gold nutritional supplement was not easily achieved, but it can be very meaningful and critical in individualized nutritional therapy. The effects of these factors on ECMO outcome require further investigation.

Although the patients’ biochemical data did not differ significantly, the lactate seemed to be a more accurate indicator of a higher survival rate (27). The lactate values of deceased and survival groups were 74.8±65 and 47.9±38 mmol/l, respectively, which were higher when compared with the normal range (lactate normal range 0.7-2.5 mmol/l). Lactate was proven to increase the risk of death in cardiac surgery (28). Although the detailed mechanism is not apparent, a higher level of lactate might be a good predictor of mortality among patients undergoing ECMO. In supporting this, Li et al. also reported that early lactate behaviors, particularly lactate clearance following ECMO support, were highly associated with in-hospital mortality in patients with postcardiotomy (28). In addition, lactate was also proven to increase the risk of death in cardiac surgery (29).

Regarding complications, the deceased group had more complications than the survival group. Zangrillo et al. conducted a meta-analysis of complications within 12 studies, finding that the most common complications associated with ECMO were renal failure, bacterial pneumonia, and bleeding (30). Our results indicate that the most common complication was multiple organ failure, which may be due to most of the patients undergoing ECMO being critically ill.

In conclusion, this study presents evidence that early nutritional intervention could benefit patients undergoing ECMO and that those who achieved a delivery goal of 80% during the first 7 days had significantly better outcomes. Enteral feeding can begin early and is well tolerated by patients receiving ECMO therapy. Most patients can tolerate bolus feeding and a standard isocaloric polymeric formula. Age, APACHE II score, and ICU and hospital stay were strongly related tooutcomes of patients with cardiopulmonary failure undergoing ECMO therapy.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The Authors thank Dr. Hong-Shiee Lai from National Taiwan University Hospital University for providing suggestions for our manuscript. This study was partly supported by grants from China Medical University Hospital and Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial and Research Center of Excellence (MOHW107-TDU-B-212-123004).

References

- 1.Sidebotham D, McGeorge A, McGuinness S, Edwards M, Willcox T, Beca J. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for treating severe cardiac and respiratory disease in adults: Part 1 – overview of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2009;23:886–892. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koning NJ, Vonk AB, van Barneveld LJ, Beishuizen A, Atasever B, van den Brom CE, Boer C. Pulsatile flow during cardiopulmonary bypass preserves postoperative microcirculatory perfusion irrespective of systemic hemodynamics. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2012;112:1727–1734. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01191.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurundkar AR, Killingsworth CR, McIlwain RB, Timpa JG, Hartman YE, He D, Karnatak RK, Neel ML, Clancy JP, Anantharamaiah GM, Maheshwari A. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation causes loss of intestinal epithelial barrier in the newborn piglet. Pediatr Res. 2010;68:128–133. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181e4c9f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giner M, Laviano A, Meguid MM, Gleason JR. In 1995 a correlation between malnutrition and poor outcome in critically ill patients still exists. Nutrition. 1996;12:23–29. doi: 10.1016/0899-9007(95)00015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heyland DK. Nutritional support in the critically ill patients. A critical review of the evidence. Crit Care Clin. 1998;14:423–440. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin CM, Doig GS, Heyland DK, Morrison T, Sibbald WJ. Multicentre, cluster-randomized clinical trial of algorithms for critical-care enteral and parenteral therapy (ACCEPT) Cmaj. 2004;170:197–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McClave SA, Martindale RG, Vanek VW, McCarthy M, Roberts P, Taylor B, Ochoa JB, Napolitano L, Cresci G. guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically Ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.) JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009;33:277–316. doi: 10.1177/0148607109335234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doig GS, Chevrou-Severac H, Simpson F. Early enteral nutrition in critical illness: a full economic analysis using US costs. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:429–436. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S50722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrie S, Herkes R, Forrest P. Nutrition support during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in adults: a retrospective audit of 86 patients. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1989–1994. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khalid I, Doshi P, DiGiovine B. Early enteral nutrition and outcomes of critically ill patients treated with vasopressors and mechanical ventilation. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19:261–268. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2010197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miessau J, Sion M, Karbowski P, Fotiou E, Hirose H, Cavarocchi N, Feldmeier C. Early enteral nutrition and outcomes of critically ill patients treated with vasopressors and mechanical ventilation. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19:261–268. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2010197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lukas G, Davies AR, Hilton AK, Pellegrino VA, Scheinkestel CD, Ridley E. Nutritional support in adult patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care Resusc. 2010;12:230–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiu LC, Tsai FC, Hu HC, Chang CH, Hung CY, Lee CS, Li SH, Lin SW, Li LF, Huang CC, Chen NH, Yang CT, Chen YC, Kao KC. Survival predictors in acute respiratory distress syndrome with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris JA, Benedict FG. A biometric study of human basal metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1918;4:370–373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.4.12.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lochs H, Allison SP, Meier R, Pirlich M, Kondrup J, Schneider S, van den Berghe G, Pichard C. Introductory to the ESPEN Guidelines on Enteral Nutrition: Terminology, definitions and general topics. Clin Nutr. 2006;25:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elsharkawy HA, Li L, Esa WA, Sessler DI, Bashour CA. Outcome in patients who require venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2010;24:946–951. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ko WJ, Lin CY, Chen RJ, Wang SS, Lin FY, Chen YS. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for adult postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:538–545. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen S, Holena D, McCunn M, Kohl B, Sarani B. A review of the fundamental principles and evidence base in the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in critically ill adult patients. J Intensive Care Med. 2011;26:13–26. doi: 10.1177/0885066610384061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smedira NG, Moazami N, Golding CM, McCarthy PM, Apperson-Hansen C, Blackstone EH, Cosgrove DM 3rd. Clinical experience with 202 adults receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for cardiac failure: survival at five years. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:92–102. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.114351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forrest P, Ratchford J, Burns B, Herkes R, Jackson A, Plunkett B, Torzillo P, Nair P, Granger E, Wilson M, Pye R. Retrieval of critically ill adults using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: an Australian experience. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:824–830. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang SC, Chen YS, Chi NH, Hsu J, Wang CH, Yu HY, Chou NK, Ko WJ, Wang SS, Lin FY. Out-of-center extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for adult cardiogenic shock patients. Artif Organs. 2006;30:24–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2006.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Assari S, Ahmadi K, Kazemi Saleh D. Gender differences in the association between lipid profile and sexual function among patients with coronary artery disease. Int Cardiovasc Res J. 2014;8:9–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chung SY, Sheu JJ, Lin YJ, Sun CK, Chang LT, Chen YL, Tsai TH, Chen CJ, Yang CH, Hang CL, Leu S, Wu CJ, Lee FY, Yip HK. Outcome of patients with profound cardiogenic shock after cardiopulmonary resuscitation and prompt extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. A single-center observational study. Circ J. 2012;76:1385–1392. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bakhtiary F, Keller H, Dogan S, Dzemali O, Oezaslan F, Meininger D, Ackermann H, Zwissler B, Kleine P, Moritz A. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for treatment of cardiogenic shock: clinical experiences in 45 adult patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:382–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Umezawa Makikado LD, Flordelis Lasierra JL, Perez-Vela JL, Colino Gomez L, Torres Sanchez E, Maroto Rodriguez B, Arribas Lopez P, Montejo Gonzalez JC. Early enteral nutrition in adults receiving venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: an observational case series. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2013;37:281–284. doi: 10.1177/0148607112451464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott LK, Boudreaux K, Thaljeh F, Grier LR, Conrad SA. Early enteral feedings in adults receiving venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2004;28:295–300. doi: 10.1177/0148607104028005295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jansen TC, van Bommel J, Woodward R, Mulder PG, Bakker J. Association between blood lactate levels, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment subscores, and 28-day mortality during early and late intensive care unit stay: a retrospective observational study. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2369–2374. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a0f919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li CL, Wang H, Jia M, Ma N, Meng X, Hou XT. The early dynamic behavior of lactate is linked to mortality in postcardiotomy patients with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support: A retrospective observational study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149:1445–1450. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindsay AJ, Xu M, Sessler DI, Blackstone EH, Bashour CA. Lactate clearance time and concentration linked to morbidity and death in cardiac surgical patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zangrillo A, Landoni G, Biondi-Zoccai G, Greco M, Greco T, Frati G, Patroniti N, Antonelli M, Pesenti A, Pappalardo F. A meta-analysis of complications and mortality of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care Resusc. 2013;15:172–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]