Abstract

Background

Outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) of Acinetobacter baumannii are cytotoxic and elicit a potent innate immune response. OMVs were first identified in A. baumannii DU202, an extensively drug-resistant clinical strain. Herein, we investigated protein components of A. baumannii DU202 OMVs following antibiotic treatment by proteogenomic analysis.

Methods

Purified OMVs from A. baumannii DU202 grown in different antibiotic culture conditions were screened for pathogenic and immunogenic effects, and subjected to quantitative proteomic analysis by one-dimensional electrophoresis and liquid chromatography combined with tandem mass spectrometry (1DE-LC-MS/MS). Protein components modulated by imipenem were identified and discussed.

Results

OMV secretion was increased > twofold following imipenem treatment, and cytotoxicity toward A549 human lung carcinoma cells was elevated. A total of 277 proteins were identified as components of OMVs by imipenem treatment, among which β-lactamase OXA-23, various proteases, outer membrane proteins, β-barrel assembly machine proteins, peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerases and inherent prophage head subunit proteins were significantly upregulated.

Conclusion

In vitro stress such as antibiotic treatment can modulate proteome components in A. baumannii OMVs and thereby influence pathogenicity.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12014-018-9204-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Proteomics, Acinetobacter baumannii, Outer membrane vesicles, Modulation by antibiotic treatment

Introduction

Acinetobacter baumannii is a major Gram-negative bacterial pathogen that causes nosocomial infections such as ventilator-associated pneumonia, bacteraemia and urinary tract infections [1]. Like most Gram-negative bacteria, A. baumannii secretes outer membrane vesicles (OMVs), as first demonstrated using the A. baumannii DU202 multidrug-resistant (MDR) clinical strain that is cytotoxic and elicits a potent innate immune response in the host [2–4]. Various peculiar biological functions of A. baumannii OMVs have been elucidated. Vaccination of whole A. baumannii OMVs alone or in combination with biofilm-associated protein (Bap) effectively protects against A. baumannii infection and elevates innate immunity [5–7]. Furthermore, the plasmid-borne blaoxa-24 gene has been transferred into the carbapenem-susceptible A. baumannii ATCC 17978 strain using carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii OMVs as a vehicle for horizontal gene transfer [8]. Therefore, elucidation of the biological roles of the protein components of OMVs is important for understanding their relevance to pathogenicity.

Numerous physiological and environmental factors are known to influence OMV secretion in Gram-negative bacteria. For example, OMV secretion is much more pronounced in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli than nonpathogenic wild-type or mutant strains [9, 10]. Additionally, antibiotics such as gentamicin, polymyxin, d-cycloserine and mitomycin C increase secretion of OMVs from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Shigella dysenteriae [11–13], and high temperature, oxidizing agents and nutrients also act as stimulatory factors for OMV production [14].

In the A. baumannii DU202 MDR clinical strain, proteomic variation in the membrane-associated protein fraction, especially among outer membrane proteins and transporters, has been correlated with antibiotic stress following treatment with imipenem and tetracycline [15]. This indicates that proteomic variation in OMVs produced by A. baumannii DU202 may occur under specific antibiotic conditions.

In the present study, we found that the production of A. baumannii DU202 OMV was increased by imipenem treatment, and became more cytotoxic toward cultured host cells. We recently reported the complete genome of A. baumannii DU202 [16], and here we used this resource to perform proteogenomic analysis of protein components of OMVs following antibiotic treatment. Bacterial OMVs play important role as potent bacterial virulence factors [17] and a high incidence of resistance to imipenem has been reported for clinical A. baumannii strains in hospitals [18, 19]. This suggests that OMVs produced under imipenem treatment might be crucial to infection; hence their characterization may be clinically important.

Methods

Bacterial strain and growth conditions

Acinetobacter baumannii DU202 cells were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth to late exponential phase (optical density of 1.0 at 600 nm) for OMV preparation. LB broth was supplemented with imipenem or tetracycline (50 µg/ml) as required.

Isolation and purification of A. baumannii OMVs

OMVs of A. baumannii DU202 were purified from bacterial culture supernatants as described previously [2]. Briefly, bacterial cells were removed by centrifugation at 6000×g for 30 min and supernatants were filtered through a 0.2 µm vacuum filter to remove residual cells and cellular debris. OMVs were ultra-filtrated and concentrated using a QuixStand Benchtop System (GE Healthcare, USA) with a 500 kDa hollow fibre membrane (GE Healthcare). Collected OMVs were precipitated by ultracentrifugation at 150,000×g for 3 h at 4 °C, and pellets containing OMVs were suspended in 0.5–1.0 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). OMV solution was further purified by sucrose gradient centrifugation (2.5, 1.6 and 0.6 M sucrose) at 200,000×g for 20 h at 4 °C. Sucrose was removed from each layer by ultracentrifugation at 150,000×g for 3 h at 4 °C, and purified OMVs were used for sterility tests and stored at − 80 °C until needed.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of OMVs was performed as described previously [20]. Briefly, OMV fractions were diluted with PBS, centrifuged at 150,000×g for 3 h, resuspended in PBS, applied to 400-mesh copper grids, stained with 2% uranyl acetate and visualized on a TEM instrument (FEI, USA) operating at 120 kV.

Sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and in-gel digestion

Sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and in-gel digestion were performed as previously described [21]. The protein concentration of purified OMVs was determined using a modified BCA assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein components of OMVs (15 µg) were separated by 12% SDS–PAGE and divided into eight fractions according to molecular weight. Sliced gels were destained in destaining solution (10 mM ammonium bicarbonate and 50% acetonitrile). After drying, gels were incubated with reducing solution (10 mM dithiothreitol and 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate) at 56 °C, and iodoacetamide (55 mM) was added to alkylate cysteine residues of disulphides. Gels were washed in 2–3 volumes of distilled water and dried in a speed vacuum concentrator. After immersing dried gels in 100 µl of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, 7–8 µl of trypsin solution (0.1 µg/µl) was added and samples were incubated at 37 °C for 12–16 h. After tryptic digestion, samples were transferred into a new tube and 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate followed by 50% acetonitrile containing 5% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) was added to recover tryptic peptide mixtures. The resulting peptide extracts were pooled and lyophilised.

Proteome analysis by liquid chromatography combined with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

Tryptic peptide mixtures were dissolved in sample buffer (0.1% formic acid and 0.02% acetic acid) and loaded onto a 2G-V/V trap column (Waters, USA). Concentrated peptides were directed onto a 10 cm × 75 μm (i.d.) C18 reversed-phase column at a flow rate of 300 nl/min. HPLC conditions and search parameters for tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analysis were applied as described previously [20]. All MS and MS/MS spectra obtained using the LTQ-Velos ESI ion trap mass spectrometer were acquired in data-dependent mode (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). For protein identification, nano liquid chromatography (LC)-MS/MS spectra were searched using MASCOT version 2.4 (Matrix Science, UK) using protein sequences from the genome of A. baumannii DU202. The exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI) was generated using MASCOT (Matrix Science) [22]. MS/MS analysis of each sample was performed at least in triplicate.

Analysis of OMV production following treatment with stressor molecules

Treatment with stressor molecules was performed s described previously [11, 23]. Briefly, pre-cultures of A. baumannii DU202 were inoculated into 250 ml of LB broth and grown to mid-log phase (OD600 ~ 0.5) at 30 °C with vigorous shaking (180 rpm). Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6000×g for 30 min and resuspended in 250 ml of fresh LB medium at 30 °C. Hydrogen peroxide, d-cycloserine and polymyxin B were added separately as required at final concentrations of 1 mM, 250 µg/ml and 2 µg/ml, respectively. To analyse the effect of hydrogen peroxide, fresh reagent was added to the culture every hour and OD600 measurements were taken. A. baumannii DU202 cells cultured in LB broth alone served as a negative control.

Animal cell culture and apoptosis assay

A549 human lung carcinoma cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 culture medium supplemented with heat-inactivated 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) under humidified 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37 °C. Cells were plated onto 12-well culture plates, and OMVs were applied and incubated for 24 h. For apoptosis assays, cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated annexin V, propidium iodide (PI) and Hoechst reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Stained cells were analysed using a NucleoCounter NC-3000 image cytometer (ChemoMetec, Denmark) [20].

Bioinformatic analysis

The subcellular locations of proteins were predicted using the subcellular location prediction program PSORTdb 2.0 (http://db.psort.org/). Transmembrane helices in membrane proteins were predicted using the TMHMM server version 2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0/). The phage region in genome of A. baumannii DU202 was analysed with PHAST [24]. Spearman correlation coefficient and scatter plots between each sample were calculated by R language (http://www.r-project.org) using value of protein abundance according MASCOT results.

Western blotting and immunoproteomics analysis

Rabbit OMVDU202 antiserum was prepared with technical assistance from Young In Frontier, Inc. (Seoul, Korea). Three injections were applied at intervals of 2 weeks, and blood was collected 1 week after the final injection. At 2 weeks after the third injection, serum was obtained by retro-orbital bleeding. For western blotting, OMV protein samples were separated by 12% SDS–PAGE, protein bands were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, CA) and the membrane was washed with TRIS-buffered saline (TBS) after blocking with 5% skim milk in TBS for 1 h. Following incubation with antiserum (1:4000 in 3% skim milk in TBS) for 14 h at 4 °C, the membrane was washed with TBST (0.5% Tween 20 in TBS) and specific IgG binding was visualised by incubation with anti-rabbit-IgG peroxidase conjugate (1:4000 in 3% skim milk in TBS) and development with a chemiluminescent substrate (GE Healthcare). The chemiluminescence signal was detected using an ImageQuant LAS 400 mini (GE Healthcare). A separate gel was used for protein identification by LC-MS/MS analysis.

Results and discussion

Antibiotics and stressor molecules induce differential production of OMVs in A. baumannii

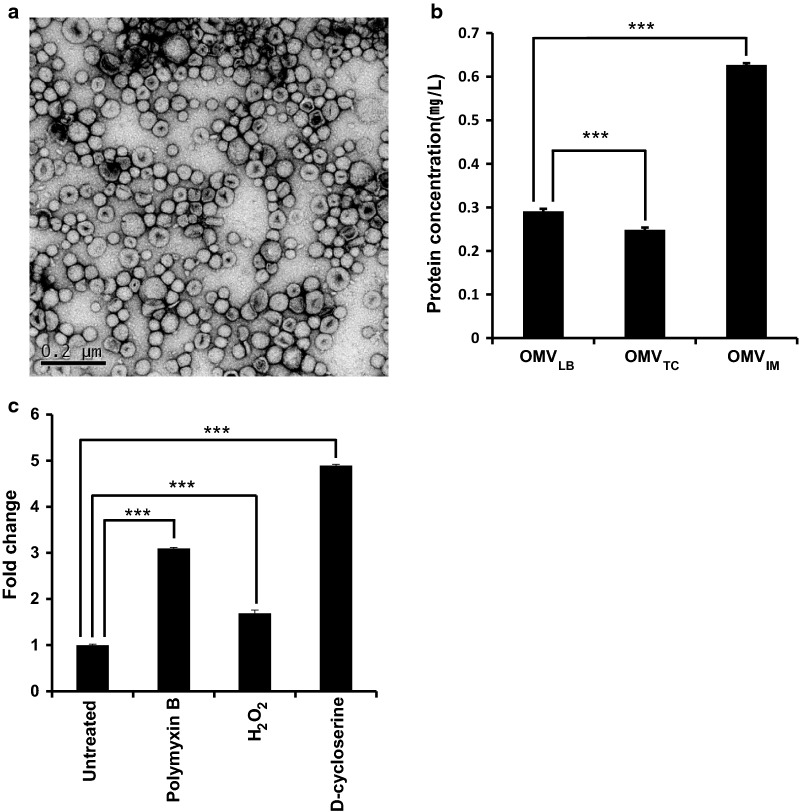

OMVs of A. baumannii DU202 were purified and designated as OMVLB (OMVs from LB culture condition), OMVIM (OMVs from imipenem culture condition) and OMVTC (OMVs from tetracycline culture condition) according to the culture conditions. Electron microscopy (EM) analysis revealed that purified OMVs were homogeneous (Fig. 1a), but the overall amount produced varied with the culture conditions (Fig. 1b and c). OMVs were increased > 2.2-fold following exposure to imipenem compared with untreated controls (Fig. 1b). Imipenem is an inhibitor of β-lactamases that inhibits cell wall synthesis in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [25]. Stressor molecules d-cycloserine, polymyxin and hydrogen peroxide were also tested, and d-cycloserine caused the largest increase in OMV production (Fig. 1c). d-cycloserine is a peptidoglycan inhibitor [11, 26], which indicates that weakening the integrity of the A. baumannii cell wall stimulates OMV production. By contrast, tetracycline, a protein synthesis inhibitor targeting the ribosome, had no effect on OMV production (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Differential production of A. baumannii DU202 OMVs according to antibiotics and stressors. Transmission electron micrograph of OMVs prepared from LB medium supplemented with imipenem (OMVIM) (a). Differential production of OMVs following treatment with antibiotics (b) and stressor molecules (c). Data are shown as means ± SD. ***p value < 0.001

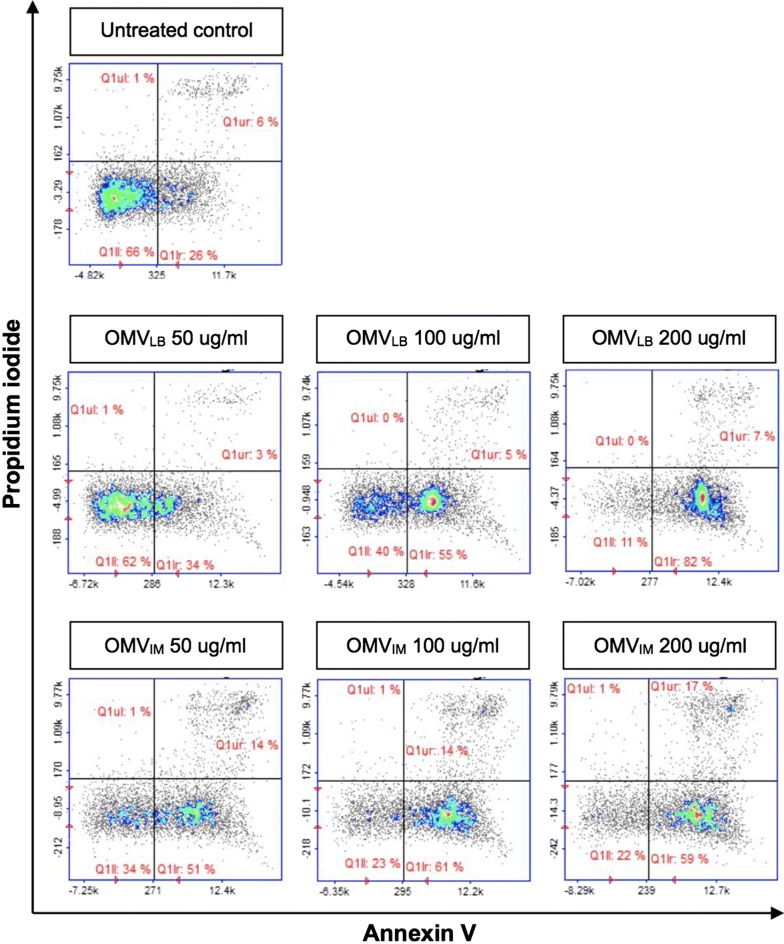

Pathogenicity of A. baumannii OMVs against cultured epithelial cells

Acinetobacter baumannii OMVs are known to be cytotoxic toward animal host cells [3]. To investigate the cytotoxicity of A. baumannii DU202 OMVs, A549 human lung carcinoma cells were treated with different concentrations of OMVLB or OMVIM. OMVLB showed moderate early apoptosis-stimulating activity, whereas OMVIM induced severe apoptotic cell death at the same concentration (Fig. 2). OMVTC also exhibited cytotoxicity toward host cells (data not shown). These results indicate that OMVs isolated from A. baumannii treated with antibiotics are more cytotoxic, and this prompted us to perform a proteomic analysis of antibiotic-induced OMVs.

Fig. 2.

Cytotoxic effect of A. baumannii DU202 OMVs. A549 human lung carcinoma cells were treated with various concentrations (0, 50, 100 and 200 µg/ml) of OMVs for 24 h, and apoptosis was assessed

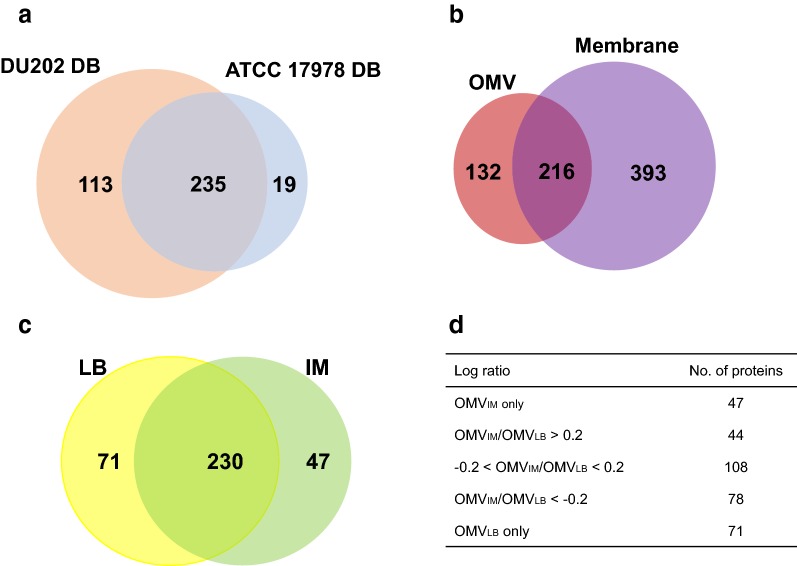

Proteogenomic characterization of A. baumannii OMVs

In our previous proteomic studies, we used the A. baumannii ATCC 17978 genome as a reference genome [15], but in the present work, we updated the reference genome with that of A. baumannii DU202. To identify protein components of A. baumannii DU202 OMVs, purified OMVs were fractionated by 12% SDS–PAGE and subjected to in-gel tryptic digestion for LC-MS/MS analysis. When using the A. baumannii ATCC 17978 genome as a reference, we identified 254 proteins in A. baumannii DU202 OMVs (Fig. 3a). A further 113 proteins were identified using the A. baumannii DU202 genome, and 19 proteins obtained using the A. baumannii ATCC 17978 genome were deleted (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Venn diagrams for comparative proteome analysis. a OMV proteomic results based on two indicated genomic databases. b Summary of proteomic analysis of two sub-proteomes (OMV vs. bacterial membrane fraction). c Comparative proteome analysis of OMVLB and OMVIM. d Quantitative summary of OMV proteomics. The numbers indicate the identified protein number

Comparative proteomic analysis of purified OMVs and bacterial membrane-associated protein fractions was performed, and as expected, not all protein components of membrane-associated protein fractions were detected in purified OMVs. Indeed, only 35.5% of the protein components (216 of 609 proteins) in membrane-associated protein fractions were also detected in the OMV proteome (Fig. 3b). Spearman correlation analysis values of commonly induced proteins in OMVs and the membrane-associated protein fractions were only 0.45–0.52, indicating a relatively poor correlation between the two proteome datasets (Additional file 1: Figure S1). These results suggest that the protein components of OMVs were differentially enriched and selectively sorted during the segregation of OMVs from host bacteria.

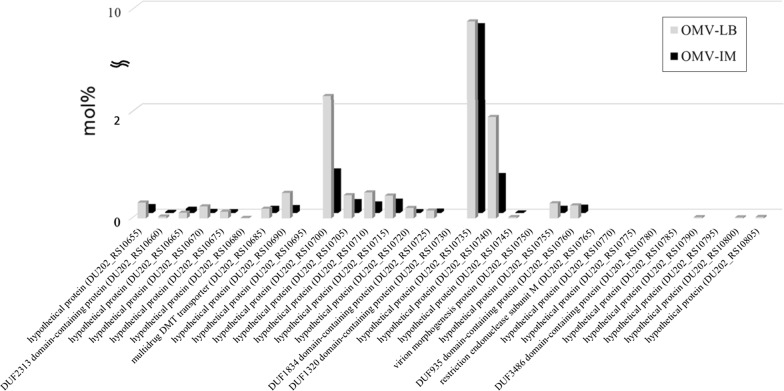

Another interesting result of proteogenomic analysis was the detection of prophage gene clusters in the genome and their expression in OMVs as major protein components (Fig. 4). The PHAST program identified eight gene clusters, including five intact bacteriophage genes, scattered throughout the genome of A. baumannii DU202. Proteomic analysis of A. baumannii DU202 OMVs revealed that, among these, four bacteriophage gene clusters (three intact and one questionable) were active in the expression of the phage components (Additional file 2: Figure S2). Mu-like prophage major head subunit (DU202_RS10735), phage major capsid proteins (DU202_RS09385) and putative proteins (DU202_RS14035, DU202_RS10700 and DU202_RS14845) were identified as major proteins in purified OMVs (Fig. 4 and Additional file 3: Table S1). Because bacteriophages and OMVs are of a similar size (50–200 nm), we cannot completely exclude the possibility of co-purification of the two particles. Indeed, several studies reported that OMVs form complexes with phages to prevent phage attack [27–29]. However, EM image analysis confirmed the high purity of OMVs (Fig. 1a), suggesting that OMV particles may contain phage proteins as major protein components. Recent genome sequencing of clinical A. baumannii strains revealed the presence of phage islands that have been classified as cryptic prophages [30]. Therefore, it was necessary to confirm whether phage proteins induced in clinical A. baumannii strains were incorporated into OMVs. Our proteomic results clearly showed differential expression of phage proteins correlated with antibiotic treatment, and about 40% of phage protein expression was downregulated following imipenem treatment (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Mu-like prophage gene cluster in A. baumannii DU202 and their expression in OMVs

Finally, genomic analysis of A. baumannii DU202 revealed the presence of four β-lactamase genes in the genome, and the proteomic results demonstrated upregulation of β-lactamase OXA-23 (DU202_RS06415) following exposure to imipenem. In particular, OXA-23 accounted for about 36% of total proteins in OMVIM, and was upregulated 9.23-fold compared with OMVLB (Table 1).

Table 1.

Differential induction of major outer membrane proteins of Acinetobacter baumannii DU202 OMV according to imipenem treatment

| Locus_tag | Description | Localization | Log ratioa | OMVLBb | OMVimipenemb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DU202_RS06415 | Carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D beta-lactamase OXA-23 | Cytoplasmic | 0.923 | 4.3782 | 36.682 |

| DU202_RS02680 | Tail-specific protease | OuterMembrane | 0.855 | 0.037 | 0.262 |

| DU202_RS15465 | Lipoprotein NlpD | Periplasmic | 0.69 | 0.051 | 0.251 |

| DU202_RS16100 | Tol–Pal system beta propeller repeat protein TolB | OuterMembrane | 0.53 | 0.168 | 0.57 |

| DU202_RS19805 | Transporter | OuterMembrane | 0.461 | 0.078 | 0.225 |

| DU202_RS12145 | Outer membrane protein assembly factor BamA | OuterMembrane | 0.46 | 0.111 | 0.319 |

| DU202_RS11840 | TonB-dependent siderophore receptor | OuterMembrane | 0.439 | 0.045 | 0.123 |

| DU202_RS15930 | Putative serine protease | OuterMembrane | 0.413 | 0.326 | 0.844 |

| DU202_RS18760 | Superoxide dismutase (Cu–Zn) | Periplasmic | 0.366 | 0.762 | 1.77 |

| DU202_RS20255 | M23 family peptidase | Periplasmic | 0.365 | 0.051 | 0.119 |

| DU202_RS01660 | Outer membrane protein W precursor | Periplasmic | 0.265 | 0.49 | 0.903 |

| DU202_RS04315 | Outer membrane protein assembly factor BamD | OuterMembrane | 0.244 | 0.106 | 0.186 |

| DU202_RS17430 | Outer membrane protein A precursor | OuterMembrane | 0.196 | 1.775 | 2.789 |

| DU202_RS00390 | FKBP-type peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerase | OuterMembrane | 0.178 | 0.083 | 0.125 |

| DU202_RS10675 | Putative bacteriophage Mu Gp45 protein | Periplasmic | − 0.579 | 0.112 | 0.03 |

| DU202_RS16695 | Succinate dehydrogenase flavoprotein subunit | Cytoplasmic | − 0.586 | 0.158 | 0.041 |

| DU202_RS17820 | Preprotein translocase subunit YajC | InnerMembrane | − 0.592 | 0.18 | 0.046 |

| DU202_RS14050 | Phage head–tail adapter protein | Cytoplasmic | − 0.61 | 0.149 | 0.037 |

| DU202_RS09385 | Phage major capsid protein | Periplasmic | − 0.632 | 1.084 | 0.253 |

| DU202_RS04220 | Peptidoglycan-binding protein LysM | Periplasmic | − 0.7 | 0.12 | 0.024 |

| DU202_RS05710 | Copper resistance protein NlpE | Extracellular | − 0.743 | 0.447 | 0.081 |

| DU202_RS09380 | HK97 family phage prohead protease | Cytoplasmic | − 0.75 | 0.214 | 0.038 |

| DU202_RS10720 | Phage tail sheath-like protein | Periplasmic | − 0.767 | 0.175 | 0.03 |

| DU202_RS13995 | Lytic transglycosylase domain-containing protein | OuterMembrane | − 0.8 | 0.16 | 0.025 |

| DU202_RS14000 | Methyl-coenzyme M reductase | OuterMembrane | − 0.967 | 0.482 | 0.052 |

| DU202_RS16690 | Succinate dehydrogenase iron-sulfur subunit | Cytoplasmic | − 1.307 | 0.154 | 0.008 |

| DU202_RS09375 | Phage portal protein | OuterMembrane | − 1.522 | 0.718 | 0.022 |

aInduction ratio was calculated as OMVLB per OMVIM

bAbundance was indicated as mol%

Imipenem induces differential expression of surface proteins in A. baumannii OMVs

Next, we compared protein contents of OMVLB and OMVIM. Of total 348 proteins, OMVLB and OMVIM shared 230 proteins, and 71 and 47 proteins were exclusively expressed in OMVLB and OMVIM, respectively (Fig. 3c, d). Above, we showed that OMVIM are more cytotoxic than OMVLB, and their protein contents are different from each other. To investigate proteins that may contribute to the cytotoxic activity of OMVIM, we focused on differentially expressed proteins between OMVLB and OMVIM, especially localized in outer membrane, periplasm and extracellular region. Eight proteases were identified in the proteome of OMVs, all of which were upregulated in the imipenem culture (Additional file 3: Table S1). Of these, putative serine protease (DU202_RS15930), M23 family peptidase (DU202_RS20255) and tail-specific protease (DU202_RS02680) were particularly highly upregulated and predicted as major outer membrane proteins (Table 1). Although the biological functions of these proteases are not yet clear, periplasmic and serine proteases have been linked to pathogenic activities in several pathogenic Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria including P. aeruginosa, E. coli and Streptococcus pyogenes [31–34]. Sequence homology analysis showed that putative serine protease (DU202_RS15930) shares significant homology (86–91% coverage, 33–34% identity) with HtrA protease and DegP from various pathogenic bacteria [35, 36]. Putative peptidase S41 (DU202_RS01365) shares high sequence similarity with CtpA of P. aeruginosa (76% coverage, 33% identity), which is cytotoxic toward host cells and essential for the type 3 secretion system [31].

Outer membrane proteins and porins (DU202_RS17430, DU202_RS01660, DU202_RS12145, DU202_RS04315 and DU202_RS16100) were also upregulated in OMVs following exposure to imipenem (Table 1). Outer membrane protein A (OmpA, DU202_RS17430) of A. baumannii is cytotoxic and involved in biofilm formation as well as adhesion, invasion and apoptosis of host cells [37–39]. In fact, OmpA is shown to contribute in the antimicrobial resistance. Disruption of OmpA gene results in decreased antibiotic resistance of A. baumannii [40]. OmpW (DU202_RS01660) is a highly immunogenic protein that elicits protective immunity against A. baumannii infections [41]. β-barrel assembly machine (BAM) proteins are outer membrane complexes responsible for folding and insertion of β-barrel outer membrane proteins, and are considered to be strong vaccine candidates in Gram-negative bacteria [42, 43]. In this study, BamA (DU202_RS12145) and BamD (DU202_RS04315) were upregulated by imipenem (Table 1), as was TolB (DU202_RS16100), which increases OMV formation in Helicobacter pylori [44].

Peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerases (PPIs) catalyse the cis/trans isomerisation of peptide bonds preceding prolyl residues during protein folding [45]. PPIs have been identified as virulence-associated proteins in bacteria such as Legionella pneumophila, Enterobacteriaceae and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis [46]. Expression of A. baumannii DU202 PPI (DU202_RS00390) was upregulated > 1.8-fold in OMVIM, and superoxide dismutase (DU202_RS18760) and lipoprotein NlpD (DU202_RS15465) were also induced in OMVs by imipenem (Table 1). These proteins have been linked to virulence in the pathogenic bacteria Neisseria meningitidis, Brucella abortus and Yersinia pestis [47, 48].

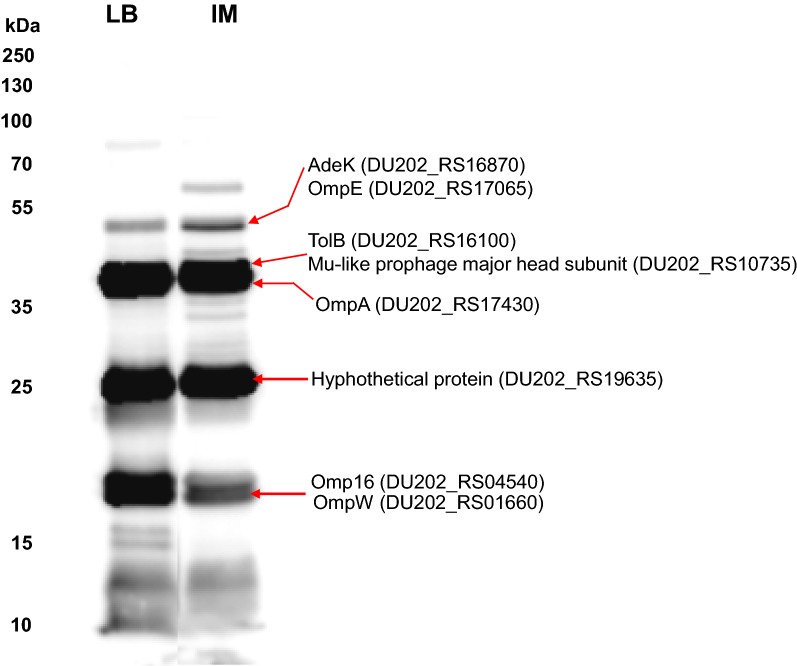

Immunogenic proteins in A. baumannii OMVIM

To identify proteins with high immunogenic activity among the A. baumannii DU202 OMV proteins that may be candidates for diagnostic markers or vaccines, western blotting was performed using the A. baumannii DU202 OMV antiserum. In previous studies, OmpA, OmpO and OmpW were identified [6]. Among the identified 348 OMV proteins, eight proteins (AdeK, OmpE, OmpA, TolB, OmpW, lipoprotein Omp16, Mu-like prophage head subunit and hypothetical protein) were predicted to be highly immunogenic (Fig. 5 and Additional file 4: Table S2). Interestingly, all are cell surface proteins (outer membrane or periplasmic) according to the subcellular prediction program, but it was not possible to differentiate between OMVLB and OMVIM.

Fig. 5.

Identification of immunogenic proteins of A. baumannii DU202 OMVs. Western blot using A. baumannii OMV antiserum revealed major immunogenic proteins. The protein bands were excised from gels identified by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analysis

Conclusions

Treatment of the A. baumannii clinical strain DU202 with imipenem increased OMV production, modified OMV proteome components and enhanced pathogenicity toward cultured host cells. A. baumannii DU202 includes several prophage gene clusters in its genome, some of which are highly expressed in OMVs. Our proteogenomic analysis successfully identified several unique genomic characteristics of OMVs from a clinical A. baumannii strain that could prove useful for developing antibiotic agents in the future.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Analysis of spearman correlation of commonly induced proteins of the OMVs and the membrane-associated protein fraction.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Expression of phage genes in A. baumannii DU202 OMV. a Complete genome of A. baumannii DU202 and proteins expression in OMVs. b Protein expression pattern of bacteriophage gene clusters in OMVs.

Additional file 3: Table S1. Comparative proteomic analysis of A. baumannii DU202 OMVs.

Additional file 4: Table S2. Proteomic analysis of immunogenic proteins of A. baumannii DU202 OMVs.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: SIK. Performed the experiments: ECP, SHY, CWC, YSY, SJ, HJR, GHK. Analyzed the data: SYL, HL, ECP, JCL. Wrote the paper: SIK, ECP, GHK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data are included in this article and additional files. Total list of identified proteins has been uploaded as an additional file.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Korea Health Technology R&D Project (HI14C2726) through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, the National Research Council of Science and Technology (NST) grant by the Korea government (MSIP) (No. CRC-16-01-KRICT), the Korea Basic Science Institute research program (C38932) and UST Young Scientist program 2018.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- OMVs

outer membrane vesicles

- 1DE-LC-MS/MS

one-dimensional electrophoresis and liquid chromatography combined with tandem mass spectrometry

- BAM

β-barrel assembly machine

- PPIs

peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerases

- MDR

multidrug-resistant

- Bap

biofilm-associated protein

- LB

Luria–Bertani

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- SDS–PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography combined with tandem mass spectrometry

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- emPAI

the exponentially modified protein abundance index

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- PI

propidium iodide

- TBS

TRIS-buffered saline

Contributor Information

Gun-Hwa Kim, Email: genekgh@kbsi.re.kr.

Seung Il Kim, Email: ksi@kbsi.re.kr.

References

- 1.Michalopoulos A, Falagas ME. Treatment of Acinetobacter infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11(5):779–788. doi: 10.1517/14656561003596350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwon SO, Gho YS, Lee JC, Kim SI. Proteome analysis of outer membrane vesicles from a clinical Acinetobacter baumannii isolate. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;297(2):150–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jin JS, Kwon SO, Moon DC, Gurung M, Lee JH, Kim SI, Lee JC. Acinetobacter baumannii secretes cytotoxic outer membrane protein A via outer membrane vesicles. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(2):e17027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jun SH, Lee JH, Kim BR, Kim SI, Park TI, Lee JC, Lee YC. Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane vesicles elicit a potent innate immune response via membrane proteins. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e71751. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang W, Yao Y, Long Q, Yang X, Sun W, Liu C, Jin X, Li Y, Chu X, Chen B, et al. Immunization against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii effectively protects mice in both pneumonia and sepsis models. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6):e100727. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McConnell MJ, Rumbo C, Bou G, Pachon J. Outer membrane vesicles as an acellular vaccine against Acinetobacter baumannii. Vaccine. 2011;29(34):5705–5710. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Badmasti F, Ajdary S, Bouzari S, Fooladi AA, Shahcheraghi F, Siadat SD. Immunological evaluation of OMV(PagL) + Bap(1-487aa) and AbOmpA(8-346aa) + Bap(1-487aa) as vaccine candidates against Acinetobacter baumannii sepsis infection. Mol Immunol. 2015;67(2):552–558. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rumbo C, Fernandez-Moreira E, Merino M, Poza M, Mendez JA, Soares NC, Mosquera A, Chaves F, Bou G. Horizontal transfer of the OXA-24 carbapenemase gene via outer membrane vesicles: a new mechanism of dissemination of carbapenem resistance genes in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(7):3084–3090. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00929-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wai SN, Takade A, Amako K. The release of outer membrane vesicles from the strains of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Microbiol Immunol. 1995;39(7):451–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb02228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horstman AL, Kuehn MJ. Bacterial surface association of heat-labile enterotoxin through lipopolysaccharide after secretion via the general secretory pathway. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(36):32538–32545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203740200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macdonald IA, Kuehn MJ. Stress-induced outer membrane vesicle production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2013;195(13):2971–2981. doi: 10.1128/JB.02267-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kadurugamuwa JL, Beveridge TJ. Virulence factors are released from Pseudomonas aeruginosa in association with membrane vesicles during normal growth and exposure to gentamicin: a novel mechanism of enzyme secretion. J Bacteriol. 1995;177(14):3998–4008. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.3998-4008.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dutta S, Iida K, Takade A, Meno Y, Nair GB, Yoshida S. Release of Shiga toxin by membrane vesicles in Shigella dysenteriae serotype 1 strains and in vitro effects of antimicrobials on toxin production and release. Microbiol Immunol. 2004;48(12):965–969. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2004.tb03626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kulp A, Kuehn MJ. Biological functions and biogenesis of secreted bacterial outer membrane vesicles. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:163–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yun SH, Choi CW, Kwon SO, Park GW, Cho K, Kwon KH, Kim JY, Yoo JS, Lee JC, Choi JS, et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis of cell wall and plasma membrane fractions from multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(2):459–469. doi: 10.1021/pr101012s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SY, Yun SH, Lee YG, Choi CW, Leem SH, Park EC, Kim GH, Lee JC, Kim SI. Proteogenomic characterization of antimicrobial resistance in extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii DU202. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(6):1483–1491. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuehn MJ, Kesty NC. Bacterial outer membrane vesicles and the host-pathogen interaction. Genes Dev. 2005;19(22):2645–2655. doi: 10.1101/gad.1299905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee Y, Kim CK, Chung HS, Yong D, Jeong SH, Lee K, Chong Y. Increasing carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli and decreasing metallo-β-lactamase producers over eight years from Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2015;56(2):572–577. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2015.56.2.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zarrilli R, Giannouli M, Tomasone F, Triassi M, Tsakris A. Carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: the molecular epidemic features of an emerging problem in health care facilities. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;3(5):335–341. doi: 10.3855/jidc.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi CW, Park EC, Yun SH, Lee SY, Lee YG, Hong Y, Park KR, Kim SH, Kim GH, Kim SI. Proteomic characterization of the outer membrane vesicle of Pseudomonas putida KT2440. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(10):4298–4309. doi: 10.1021/pr500411d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yun SH, Park GW, Kim JY, Kwon SO, Choi CW, Leem SH, Kwon KH, Yoo JS, Lee C, Kim S, et al. Proteomic characterization of the Pseudomonas putida KT2440 global response to a monocyclic aromatic compound by iTRAQ analysis and 1DE-MudPIT. J Proteomics. 2011;74(5):620–628. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishihama Y, Oda Y, Tabata T, Sato T, Nagasu T, Rappsilber J, Mann M. Exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI) for estimation of absolute protein amount in proteomics by the number of sequenced peptides per protein. Mol Cell Proteomics MCP. 2005;4(9):1265–1272. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500061-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van de Waterbeemd B, Zomer G, van den Ijssel J, van Keulen L, Eppink MH, van der Ley P, van der Pol LA. Cysteine depletion causes oxidative stress and triggers outer membrane vesicle release by Neisseria meningitidis; implications for vaccine development. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e54314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Y, Liang Y, Lynch KH, Dennis JJ, Wishart DS. PHAST: a fast phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(1):W347–W352. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clissold SP, Todd PA, Campoli-Richards DM. Imipenem/cilastatin. A review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1987;33(3):183–241. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198733030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prosser GA, de Carvalho LP. Kinetic mechanism and inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosisd-alanine:d-alanine ligase by the antibiotic d-cycloserine. FEBS J. 2013;280(4):1150–1166. doi: 10.1111/febs.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manning AJ, Kuehn MJ. Contribution of bacterial outer membrane vesicles to innate bacterial defense. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:258. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biller SJ, Schubotz F, Roggensack SE, Thompson AW, Summons RE, Chisholm SW. Bacterial vesicles in marine ecosystems. Science. 2014;343(6167):183–186. doi: 10.1126/science.1243457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Devos S, Van Putte W, Vitse J, Van Driessche G, Stremersch S, Van Den Broek W, Raemdonck K, Braeckmans K, Stahlberg H, Kudryashev M, et al. Membrane vesicle secretion and prophage induction in multidrug-resistant Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in response to ciprofloxacin stress. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19(10):3930–3937. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Di Nocera PP, Rocco F, Giannouli M, Triassi M, Zarrilli R. Genome organization of epidemic Acinetobacter baumannii strains. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:224. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seo J, Darwin AJ. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa periplasmic protease CtpA can affect systems that impact its ability to mount both acute and chronic infections. Infect Immun. 2013;81(12):4561–4570. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01035-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maeda H, Yamamoto T. Pathogenic mechanisms induced by microbial proteases in microbial infections. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1996;377(4):217–226. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1996.377.4.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones CH, Bolken TC, Jones KF, Zeller GO, Hruby DE. Conserved DegP protease in gram-positive bacteria is essential for thermal and oxidative tolerance and full virulence in Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect Immun. 2001;69(9):5538–5545. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5538-5545.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoy B, Geppert T, Boehm M, Reisen F, Plattner P, Gadermaier G, Sewald N, Ferreira F, Briza P, Schneider G, et al. Distinct roles of secreted HtrA proteases from gram-negative pathogens in cleaving the junctional protein and tumor suppressor E-cadherin. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(13):10115–10120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C111.333419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ingmer H, Brondsted L. Proteases in bacterial pathogenesis. Res Microbiol. 2009;160(9):704–710. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cortes G, de Astorza B, Benedi VJ, Alberti S. Role of the htrA gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae virulence. Infect Immun. 2002;70(9):4772–4776. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.4772-4776.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi CH, Lee JS, Lee YC, Park TI, Lee JC. Acinetobacter baumannii invades epithelial cells and outer membrane protein A mediates interactions with epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:216. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi CH, Hyun SH, Lee JY, Lee JS, Lee YS, Kim SA, Chae JP, Yoo SM, Lee JC. Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A targets the nucleus and induces cytotoxicity. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10(2):309–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaddy JA, Tomaras AP, Actis LA. The Acinetobacter baumannii 19606 OmpA protein plays a role in biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces and in the interaction of this pathogen with eukaryotic cells. Infect Immun. 2009;77(8):3150–3160. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00096-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smani Y, Fabrega A, Roca I, Sanchez-Encinales V, Vila J, Pachon J. Role of OmpA in the multidrug resistance phenotype of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(3):1806–1808. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02101-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang W, Wang S, Yao Y, Xia Y, Yang X, Long Q, Sun W, Liu C, Li Y, Ma Y. OmpW is a potential target for eliciting protective immunity against Acinetobacter baumannii infections. Vaccine. 2015;33(36):4479–4485. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Namdari F, Hurtado-Escobar GA, Abed N, Trotereau J, Fardini Y, Giraud E, Velge P, Virlogeux-Payant I. Deciphering the roles of BamB and its interaction with BamA in outer membrane biogenesis, T3SS expression and virulence in Salmonella. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e46050. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang JH, Tong J, Tan KS, Gabriel K. From evolution to pathogenesis: the link between beta-barrel assembly machineries in the outer membrane of mitochondria and gram-negative bacteria. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(7):8038–8050. doi: 10.3390/ijms13078038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turner L, Praszkier J, Hutton ML, Steer D, Ramm G, Kaparakis-Liaskos M, Ferrero RL. Increased outer membrane vesicle formation in a Helicobacter pylori tolB Mutant. Helicobacter. 2015;20(4):269–283. doi: 10.1111/hel.12196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gothel SF, Marahiel MA. Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerases, a superfamily of ubiquitous folding catalysts. Cell Mol Life Sci CMLS. 1999;55(3):423–436. doi: 10.1007/s000180050299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Unal CM, Steinert M. Microbial peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerases (PPIases): virulence factors and potential alternative drug targets. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev MMBR. 2014;78(3):544–571. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00015-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pratt AJ, DiDonato M, Shin DS, Cabelli DE, Bruns CK, Belzer CA, Gorringe AR, Langford PR, Tabatabai LB, Kroll JS, et al. Structural, functional, and immunogenic insights on Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase pathogenic virulence factors from Neisseria meningitidis and Brucella abortus. J Bacteriol. 2015;197(24):3834–3847. doi: 10.1128/JB.00343-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tidhar A, Flashner Y, Cohen S, Levi Y, Zauberman A, Gur D, Aftalion M, Elhanany E, Zvi A, Shafferman A, et al. The NlpD lipoprotein is a novel Yersinia pestis virulence factor essential for the development of plague. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(9):e7023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Analysis of spearman correlation of commonly induced proteins of the OMVs and the membrane-associated protein fraction.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Expression of phage genes in A. baumannii DU202 OMV. a Complete genome of A. baumannii DU202 and proteins expression in OMVs. b Protein expression pattern of bacteriophage gene clusters in OMVs.

Additional file 3: Table S1. Comparative proteomic analysis of A. baumannii DU202 OMVs.

Additional file 4: Table S2. Proteomic analysis of immunogenic proteins of A. baumannii DU202 OMVs.

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in this article and additional files. Total list of identified proteins has been uploaded as an additional file.