Abstract

Introduction

Contemporary data regarding the effect of age, especially in elderly patients, on cancer-specific mortality (CSM) for pT1a renal cell carcinoma (RCC) are lacking. The objective of the current study is to evaluate CSM in a large population-based cohort of surgically treated pT1a RCC patients according to age groups.

Methods

Within the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results database (2000–2013), we identified 37 121 pT1a RCC patients who underwent either partial or radical nephrectomy. The population was stratified into five groups according to decades: <50, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, and ≥80 years. The effect of age on CSM was evaluated using competing risks regression models according to Fuhrman grade (FG). Analyses were repeated in clear-cell RCC (ccRCC).

Results

Patients aged 50–59 (9615), 60–69 (10 762), 70–79 (7096), and ≥80 (1789) years demonstrated higher rate of CSM compared to patients aged <50 (7856) years (hazard ratios [HR] 2.11, 3.04, 4.47, and 7.56, respectively; all p<0.001). The effect of age on CSM in FG 1–2 patients resulted in HRs ranging from 2.01–8.23 for the same age decades (all p< 0.001). Similarly, the effect of age on CSM in FG 3–4 patients resulted in HRs ranging from 2.38–5.92, respectively (all p<0.001). Virtually the same results were recorded in ccRCC patients.

Conclusions

Older age is associated with higher CSM in surgically treated patients with pT1a RCC. This effect seems to be more pronounced in patient with FG 1–2 disease. This observation should be considered when making treatment decisions in elderly patients.

Introduction

Recent evidence supports increasing incidence of several solid tumours, including renal cell carcinoma (RCC), over the next 20 years.1 Moreover, advanced age and increasing life expectancy combined with increasing incidental radiological detection of small renal masses (SRMs)2 are likely contribute to continued increase in SRM incidence among the elderly.

In general, elderly patients are expected to harbour disease with more favourable natural history.3–5 However, some investigators reported that advanced age might represent a risk factor for more aggressive and/or more rapidly progressive RCC.6 This observation has not been validated in contemporary patients.

In consequence, we decided to test the effect of age on cancer-specific mortality (CSM) in patients with SRMs treated with either partial or radical nephrectomy within the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database from 2000–2013. We paid special attention on elderly patients.

Methods

Study cohorts

The current study relied on the SEER database, which represents approximately a 30% sample of the U.S. population and approximates its demographic composition, as well as cancer incidence and mortality.7

In the SEER database, we focused on subjects over 18 years old, diagnosed between 2000 and 2013 with histologically confirmed RCC (International Classification of Disease for Oncology [ICD-O-3], site code C64.9). Only patients with clear-cell (ccRCC) (histologic code 8310 and 8312),8,9 chromophobe (chRCC) (histologic code 8317),10 and papillary (pRCC) (histologic code 8260)11 histology were considered. All were surgically treated with either partial or radical nephrectomy. For the purpose of the study, we only considered pT1a disease. Exclusion criteria consisted of bilateral RCC, lymph node metastases (N1), distant metastases (M1), unknown Fuhrman grade (FG), and unknown lymph node stage (N) or M stages.

Description of covariates

Data on age, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)-based T, N, and M stages were acquired at the time of diagnosis. Additional variables consisted of race (African Americans, White, and other), marital status (married, unmarried, unknown), gender, and year of surgery.

According to age at diagnosis, the population was stratified into five groups using 10-year age intervals: <50, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, and ≥80 years. Similarly, FG was categorized into two groups: FG 1–2 and FG 3–4.

CSM was defined according to the SEER mortality code (code 28010). All other deaths were considered as other-cause mortality (OCM).

Statistical analysis

Medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), as well as frequencies and proportions, were reported for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The statistical significance of differences in medians and proportions was evaluated with the Kruskal-Wallis and Chi-square tests.

Competing-risks regression (CRR) methodology assessed CSM.12 CRR accounts for the effect of OCM and provides the most unbiased estimate of CSM. Age-stratified cumulative incidence rates were generated and compared with the Gray test.13 Subsequently, univariable and multivariable (MVA) CRR models were used to test the effect of age (at <50, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, and ≥80 years) on CSM rates. Covariates included gender, race, year of diagnosis, histological subtype, and N stage (N0/Nx). To assess the magnitude of the effect related to age, we repeated the MVA CRR models after stratifying according to FG 1–2 and FG 3–4. Finally, we relied on subgroup analyses that focused on individuals with ccRCC, where we repeated all previous analyses.

All statistical tests were two-sided with a level of significance set at p<0.05. Analyses were performed using the R software environment for statistical computing and graphics (version 3.3.0; http://www.r-project.org/).

Results

We identified 37 121 individuals with pT1a, N0/Nx, M0 between 200 and 2013. The median age was 61 years (IQR 51–69). Following stratification of patients according to age groups, 7859 (21.2%), 9615 (25.9%), 10 762 (29.0%), 7096 (19.1%), and 1789 (4.8%) of patients were aged <50, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, and ≥80 years, respectively. Most were male (22 481, 60.6%), Caucasian (30 507; 82.2%), married (23 758; 64.0%), harboured ccRCC (30 220, 81.4%), FG 1–2 (29 604, 79.8%), and N0 (36 204, 97.5%) stage. Partial nephrectomy was performed in 18 669 (50.3%) (Table 1). Some baseline characteristics differed according to age groups. For example, a higher proportion of female, unmarried, and Caucasian patients were aged ≥80 years relative to those aged <80 years (p<0.001). Moreover, the oldest patients were more likely to be treated with radical nephrectomy (70.2% vs. 29.8%; p<0.001).

Table 1.

Clinical and pathological characteristics of 37 121 patients with pT1a N0/Nx M0 renal cell cancer treated with radical or partial nephrectomy from 2000–2013

| Variables | Patient population stratified according to age categories (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Overall: 37 121 (100) | <50 yrs: 7 856 (21.2) | 50–59 yrs: 9 615 (25.9) | 60–69 yrs: 10 762 (29.0) | 70–79 yrs: 7 096 (19.1) | ≥80 yrs: 1 789 (4.8) | |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||

| Median (range) | 2008 (2005–2011) | 2008 (2005–2011) | 2008 (2005–2011) | 2008 (2005–2011) | 2008 (2004–2011) | 2007 (2004–2010) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 22 481 (60.6) | 4697 (59.8) | 6034 (62.8) | 6666 (61.9) | 4160 (58.6) | 924 (51.6) |

| Female | 14 640 (39.4) | 3162 (40.2) | 3581 (37.2) | 4096 (38.1) | 2936 (41.4) | 865 (48.4) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 30 507 (82.2) | 6368 (81) | 7711 (80.2) | 8866 (82.4) | 5965 (84.1) | 1597 (89.3) |

| Black | 4307 (11.6) | 927 (11.8) | 1317 (13.7) | 1260 (11.7) | 693 (9.8) | 110 (6.1) |

| Other | 2053 (5.5) | 480 (6.1) | 506 (5.3) | 581 (5.4) | 406 (5.7) | 80 (4.5) |

| Unknown | 254 (0.7) | 84 (1.1) | 81 (0.8) | 55 (0.5) | 32 (0.5) | 2 (0.1) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||||

| Married | 23 758 (64) | 4715 (60) | 6368 (66.2) | 7250 (67.4) | 4496 (63.4) | 929 (51.9) |

| Unknown | 1614 (4.3) | 369 (4.7) | 391 (4.1) | 510 (4.7) | 274 (3.9) | 70 (3.9) |

| Unmarried | 11 749 (31.7) | 2775 (35.3) | 2856 (29.7) | 3002 (27.9) | 2326 (32.8) | 790 (44.2) |

| Surgical approach, n (%) | ||||||

| Partial nephrectomy | 18 669 (50.3) | 4 475 (56.9) | 5070 (52.7) | 5560 (51.7) | 3031 (42.7) | 533 (29.8) |

| Radical nephrectomy | 18 452 (49.7) | 3 384 (43.1) | 4545 (47.3) | 5202 (48.3) | 4065 (57.3) | 1256 (70.2) |

| Tumour size (cm) | ||||||

| Median (range) | 2.7(2.0–3.5) | 2.5 (1.9–3.2) | 2.6 (2.0–3.4) | 2.7 (2.0–3.5) | 2.8 (2.1–3.5) | 3.0 (2.4–3.5) |

| Histology, n (%) | ||||||

| ccRCC | 30 220 (81.4) | 6 652 (84.6) | 7812 (81.2) | 8587 (79.8) | 5730 (80.7) | 1439 (80.4) |

| pRCC | 5 281 (14.2) | 876 (11.1) | 1419 (14.8) | 1712 (15.9) | 1045 (14.7) | 229 (12.8) |

| chRCC | 1 620 (4.4) | 331 (4.2) | 384 (4) | 463 (4.3) | 321 (4.5) | 121 (6.8) |

| Fuhrman grade (FG), n (%) | ||||||

| FG 1–2 | 29 604 (79.8) | 6513 (82.9) | 7693 (80) | 8469 (78.7) | 5552 (78.2) | 1377 (77) |

| FG 3–4 | 7517 (20.2) | 1346 (17.1) | 1922 (20) | 2293 (21.3) | 1544 (21.8) | 412 (23) |

| N stage, n (%) | ||||||

| N0 | 36 204 (97.5) | 7650 (97.3) | 9399 (97.8) | 10 513 (97.7) | 6913 (97.4) | 1729 (96.6) |

| NX | 917 (2.5) | 209 (2.7) | 216 (2.2) | 249 (2.3) | 183 (2.6) | 60 (3.4) |

ccRCC: clear-cell renal cell carcinoma; chRCC: chromophobe renal cell carcinoma; pRCC: papillar.y renal cell carcinoma.

Cumulative incidence and competing risk analyses

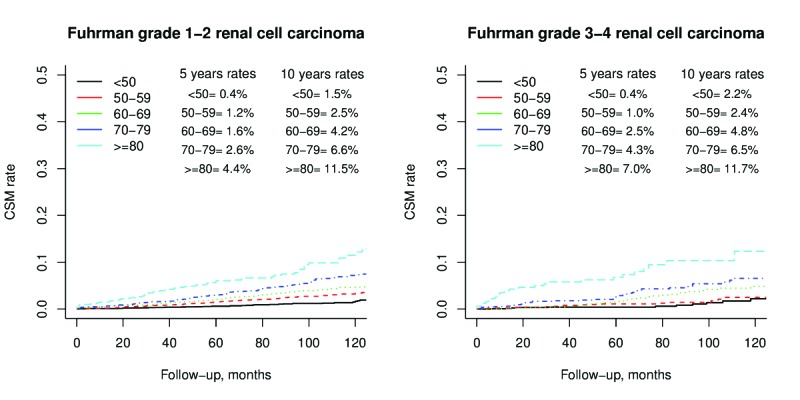

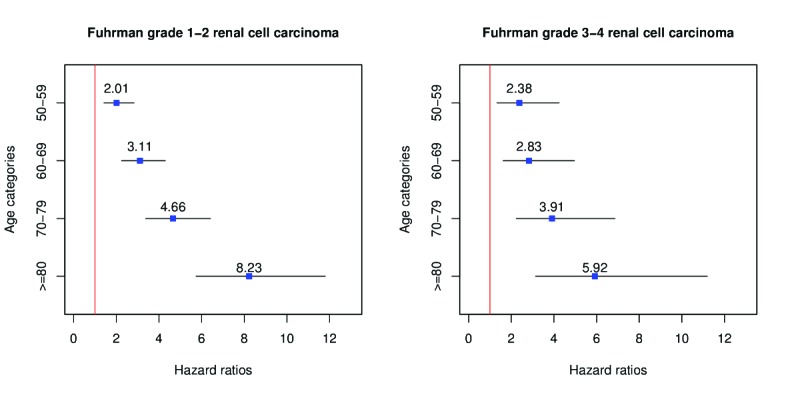

The number of deaths from CSM and OCM for the entire cohort, stratified according to age group and histological subtype, is illustrated in Table 2. Overall five- and 10-year CSM rates, after accounting for OCM, were 0.5% and 1.5%, respectively for patients aged <50 year, 1.4% and 3.1% for those aged 50–59, 1.9% and 4.4% for those aged 60–69, 3.0% and 6.9% for those aged 70–79, and 6.2% and 11.6% for patients aged >80 years (all p<0.001). When cumulative incidences of CSM rates were stratified according to FG, elderly patients exhibited higher CSM rates than their younger counterparts (Fig. 1). In MVA CRR models that focused on the entire cohort, age-specific hazard ratios (HRs) predicting CSM were 2.1, 3.0, 4.5, and 7.6-fold higher, respectively, for patients aged 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, and ≥80 years than their counterparts aged <50 years. In separate MVA CRR models that focused on FG 1–2, age-specific HRs ranged from 2.0–8.2 for the same age groups (all p<0.001). Finally, in MVA CRR models focused on FG 3–4, age-specific HRs ranged from 2.4–5.9 (all p<0.001) (Fig. 2). Virtually the same results were obtained for patients with ccRCC (data not shown).

Table 2.

Cause-of-death information within the entire population and stratified according to age group and renal cell carcinoma histological subtype

| Age categories (yr) | <50 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | ≥80 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall population | |||||

| Any FG | |||||

| Patients, n | 7856 | 9615 | 10 762 | 7096 | 1789 |

| CSM (%) | 61 (0.8) | 159 (1.7) | 242 (2.2) | 261 (3.7) | 112 (6.3) |

| OCM (%) | 268 (3.4) | 509 (5.3) | 808 (7.5) | 938 (13.2) | 354 (19.8) |

| OM (%) | 329 (4.2) | 668 (6.9) | 1050 (9.8) | 1 199(16.9) | 466 (26.0) |

| FG 1–2 | |||||

| Patients, n | 6 513 | 7 693 | 8 469 | 5 552 | 1377 |

| CMS (%) | 46 (0.7) | 110 (1.4) | 175 (2.1) | 195 (3.5) | 85 (6.2) |

| OCM (%) | 213 (3.3) | 412 (5.4) | 658 (7.8) | 764 (13.8) | 275 (20.0) |

| OM (%) | 259 (4.0) | 522 (6.8) | 833 (9.8) | 959 (17.3) | 360 (26.1) |

| FG 3–4 | |||||

| Patients, n | 1 346 | 1 922 | 2293 | 1 544 | 412 |

| CSM (%) | 15 (1.1) | 49 (2.5) | 67 (2.9) | 66 (4.3) | 27 (6.6) |

| OCM (%) | 55 (4.1) | 97 (5.0) | 150 (6.5) | 174 (11.3) | 79 (19.2) |

| OM (%) | 70 (5.2) | 146 (7.6) | 217 (9.5) | 240 (15.5) | 106 (25.7) |

| ccRCC cohorts | |||||

| Any FG | |||||

| Patients, n | 6 652 | 7 812 | 8587 | 5 730 | 1439 |

| CSM (%) | 57 (0.9) | 132 (1.7) | 204 (2.4) | 216 (3.8) | 95 (6.6) |

| OCM (%) | 221 (3.3) | 419 (5.4) | 681 (7.9) | 802 (14.0) | 308 (21.4) |

| OM (%) | 278 (4.2) | 551 (7.1) | 885 (10.3) | 1018 (17.8) | 403 (28.0) |

| FG 1–2 | |||||

| Patients, n | 5 228 | 6 264 | 6887 | 4 573 | 1115 |

| CSM (%) | 44 (0.8) | 112 (1.8) | 165 (2.4) | 174 (3.8) | 70 (6.3) |

| OCM (%) | 181 (3.5) | 337 (5.4) | 570 (8.3) | 634 (13.9) | 241 (21.6) |

| OM (%) | 225 (4.3) | 449 (7.2) | 735 (10.7) | 808 (17.7) | 311 (27.9) |

| FG 3–4 | |||||

| Patients, n | 1 424 | 1 548 | 1700 | 1 157 | 324 |

| CSM (%) | 13 (0.9) | 20 (1.3) | 39 (2.3) | 42 (3.6) | 25 (7.7) |

| OCM (%) | 40 (2.8) | 82 (5.3) | 111 (6.5) | 168 (14.5) | 67 (20.7) |

| OM (%) | 53 (3.7) | 102 (6.6) | 150 (8.8) | 210 (18.2) | 92 (28.4) |

ccRCC: clear-cell renal cell carcinoma; CSM: cancer-specific mortality; FG: Fuhrman grade; OCM: other-cause mortality; OM: overall mortality.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative incidence plots depicting cancer specific mortality rates stratified according to age categories (all Grey tests p<0.001) for Fuhrman grade 1–2 (left) and Fuhrman grade 3–4 (right) renal cell carcinoma.

Fig. 2.

Graphical representation of multivariable competing-risks regression (CRR) predicting cancer-specific mortality (CSM) in patients with small renal masses. Derived hazard ratios are depicted according to age categories for Fuhrman grade 1–2 (left) and Fuhrman grade 3–4 (right). CRR has been adjusted for age, race, sex, marital status, histology type of renal cell cancer, type of nephrectomy, and N status.

Discussion

We tested the hypothesis that elderly patients might harbour SRMs with more favourable natural history. Our analyses consisted of several steps. First, we examined the effect of age on CSM for the entire population of surgically treated RCC. Then, we repeated the analyses after stratification for FG 1–2 and 3–4. Finally, we repeated all tests only on individuals who harboured ccRCC histological subtype.

Our results identify several important observations. First, they rejected our hypothesis about the potentially less aggressive SRMs in elderly patients. They also demonstrated that surgically treated elderly patients have higher CSM rates than their younger counterparts. Specifically, more advanced patient age predisposed to substantially higher CSM rates even after adjusting for all covariates and OCM. In particular, the effect of age increased the magnitude of CSM rates according to examined age decades, in a stepwise and chronological fashion.

To expand the complexity of hypothesis-testing, we postulated that the effect of age may vary according to FG. FG-stratified analyses indeed showed that the magnitude of CSM rate differences, according to age, is greater in patients with FG 1–2 that in those with FG 3–4. We postulated that the favourable tumour grade is in itself associated with slower disease progression and, in consequence, it allows the effect of age to become more easily detectable than in patients with FG 3–4. Several explanations may be proposed as to why the prognosis of elderly patients with SRMs and FG 1–2 disease is significantly worse than that of their younger counterparts. First, the natural history of RCC may be more aggressive in the elderly. Second, elderly patients may be more likely to be investigated or treated in a less timely fashion. Third, the adherence to treatment or active surveillance guidelines may be less rigorous in the elderly than in their younger counterparts because of physician or patient considerations.

Finally, we hypothesized that patients with the most prevalent and aggressive histological subtypes, manly ccRCC, may exhibit a different relationship between age and CSM. To address this consideration, we repeated the analyses including only patients with ccRCC. Moreover, we performed this secondary analysis even after stratification for FG 1–2 vs. 3–4. The analyses revealed that our findings were virtually the same as those reported for the entire cohort. In consequence, it can be postulated that the effect of age does not vary according to histology subtype even when analyses where restricted to ccRCC.

It should also be considered that patients with SRM are infrequently diagnosed with unusual RCC variants, such as sarcomatoid and unclassified RCC. Indeed, only 57 (0.2%) of sarcomatoid and 10 (0.03%) of unclassified RCC were identified with T1a substage within the SEER database.

Our results are in agreement with the one and only historical study that focused on the effect of age on CSM in the SEER database. In that report, Sun et al identified age as a predictor of higher CSM among other than stage I RCC.6 Their analyses included patients diagnosed until 2006, which may no longer be applicable to contemporary disease phenotype. In addition to its contemporary nature, our study also relied on a larger patient population, which increases the generalizability of its findings. Moreover, our study’s scope of hypothesis-testing extended beyond of that previous report, as it focused on FG and histological subtypes. However, unlike the previous report, we did not address the effect of age on all stage of RCC. Despite these advantages, our results indicate that the natural history of surgically treated SRMs remain relatively unchanged with respect to its relationship with patient age.

It is of note that several other retrospective studies also address the relationship between age and CSM in RCC; however, none of them focused on patients with SRMs. Additionally, only one study, authored by Komai et al,14 recorded a survival advantage in young patients with T1–T2 RCC stages relative to the older counterparts. Second, Aziz et al relied on the CORONA database and also showed that young patients (<40 years) had lower CSM compared to the older counterparts within a cohort of patients with stage T1–4, N0–1, M0–1.15 Finally, Rampersaud et al confirmed the less aggressive natural history of RCC for patients age <59 years relative to those aged ≥60 years across all localized and non-localized stages (T1–4, N0–1, M0–1).16 It should also be noted that three single-institution studies failed to show a statistically significant relationship between age and CSM in patients with RCC. Specifically, Hollingsworth et al17 reported a lack of statistically significant difference between young and old individuals in regard to CSM considering stages T1–2, N0, M0 RCC, while Thompson et al18 and Gillett et al19 did not observe a significant CSM disadvantage for individuals with older age considering localized (T1–4, N0, M0) and non-localized (any T, N1 or M1) RCC.

Our study is not devoid of limitations. First, the SEER database does not include baseline performance status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) and comorbidities. The use of CRR may account for the effect of comorbidities by virtue of adjusting for OCM. Additionally, the SEER database represents a large, although nonetheless partial population sample that may not perfectly reflect the entire population of the U.S. However, these and other limitations are shared with other large-scale, population-based studies.17,20 Last but not least, the higher rates of CSM observed in elderly patients may be related to a selection bias for those who received surgical management. In other words, elderly patients who were candidates for either partial or radical nephrectomy may have received surgery instead of surveillance or watchful waiting because of more rapidly growing cancer, compared to younger patients. In consequence, the higher CSM rate in elderly patients might be related to disparities in tumour progression between young and old. However, the presence of this bias cannot be ascertained in our study, since we only included patients treated with either partial or radical nephrectomy and excluded those who underwent watchful waiting or active surveillance.

Taken together, the potential surgical selection bias may limit the generalizability of our findings to only surgically treated patients. In consequence, despite stage I RCC in elderly patients being associated with worse survival, the uncontrolled design of our study exposed our findings to the effect of such bias

Conclusion

Our data indicate that older age is associated with higher CSM in surgically treated patients with pT1a RCC. This effect seems to be more pronounced in patient with FG 1–2 disease. This observation should be considered when making treatment decisions in elderly patients

Footnotes

Competing interests: Dr. Kapoor has been an advisor for and participated in clinical trials supported by Amgen, Astellas, Janssen, GSK, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi. The remaining authors report no competing personal or financial interests related to this work.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Smittenaar CR, Petersen KA, Stewart K, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality projections in the UK until 2035. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:1147–55. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kane CJ, Mallin K, Ritchey J, et al. Renal cell cancer stage migration: Analysis of the National Cancer Data Base. Cancer. 2008;113:78–83. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandt J, Garne JP, Tengrup I, et al. Age at diagnosis in relation to survival following breast cancer: A cohort study. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:33. doi: 10.1186/s12957-014-0429-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sacher AG, Dahlberg SE, Heng J, et al. Association between younger age and targetable genomic alterations and prognosis in non-small-cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:313–20. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Kobayashi K, et al. Prognosis and growth activity depend on patient age in clinical and subclinical papillary thyroid carcinoma. Endocr J. 2014;61:205–13. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ13-0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun M, Abdollah F, Bianchi M, et al. A stage-for-stage and grade-for-grade analysis of cancer-specific mortality rates in renal cell carcinoma according to age: A competing-risks regression analysis. Eur Urol. 2011;60:1152–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noone A-M, Cronin KA, Altekruse SF, et al. Cancer incidence and survival trends by subtype using data from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program, 1992–2013. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26:632–41. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scoll BJ, Wong Y-N, Egleston BL, et al. Age, tumour size, and relative survival of patients with localized renal cell carcinoma: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results analysis. J Urol. 2009;181:506–11. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shuch B, Hofmann JN, Merino MJ, et al. Pathologic validation of renal cell carcinoma histology in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program. Urol Oncol. 2014;32:23.e9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daugherty M, Blakely S, Shapiro O, et al. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma is the most common non-clear renal cell carcinoma in young women: Results from the SEER database. J Urol. 2016;195:847–51. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.10.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Truong H, Hegarty SE, Gomella LG, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of patients with suspected inherited renal cell cancer: Application of the ACMG/NSGC genetic referral guidelines to patient cohorts. J Genet Couns. 2017;26:548–55. doi: 10.1007/s10897-016-0020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scrucca L, Santucci A, Aversa F. Regression modelling of competing risk using R: An in-depth guide for clinicians. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:1388–95. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Logan BR, Zhang M-J. The use of group sequential designs with common competing risks tests. Stat Med. 2013;32:899–913. doi: 10.1002/sim.5597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komai Y, Fujii Y, Iimura Y, et al. Young age as favourable prognostic factor for cancer-specific survival in localized renal cell carcinoma. Urology. 2011;77:842–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aziz A, May M, Zigeuner R, et al. for the members of the CORONA Project and the Young Academic Urologists Renal Cancer Group. Do young patients with renal cell carcinoma feature a distinct outcome after surgery? A comparative analysis of patient age based on the multinational CORONA database. J Urol. 2014;191:310–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rampersaud EN, Klatte T, Bass G, et al. The effect of gender and age on kidney cancer survival: Younger age is an independent prognostic factor in women with renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2014;32:30.e9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hollingsworth JM, Miller DC, Daignault S, et al. Five-year survival after surgical treatment for kidney cancer: A population-based competing risk analysis. Cancer. 2007;109:1763–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson RH, Ordonez MA, Iasonos A, et al. Renal cell carcinoma in young and old patients — is there a difference? J Urol. 2008;180:1262–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillett MD, Cheville JC, Karnes RJ, et al. Comparison of presentation and outcome for patients 18–40 and 60–7 years old with solid renal masses. J Urol. 2005;173:1893–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000158157.57981.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kutikov A, Egleston BL, Wong Y-N, et al. Evaluating overall survival and competing risks of death in patients with localized renal cell carcinoma using a comprehensive nomogram. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:311–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]