Abstract

Early co-transcriptional events during eukaryotic ribosome assembly result in the formation of precursors of the small (40S) and large (60S) ribosomal subunits1. A multitude of transient assembly factors regulate and chaperone the systematic folding of preribosomal RNA subdomains. However, owing to a lack of structural information, the role of these factors during early nucleolar 60S assembly is not fully understood. Here we report cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) reconstructions of the nucleolar pre-60S ribosomal subunit in different conformational states at resolutions of up to 3.4 Å. These reconstructions reveal how steric hindrance and molecular mimicry are used to prevent both premature folding states and binding of later factors. This is accomplished by the concerted activity of 21 ribosome assembly factors that stabilize and remodel pre-ribosomal RNA and ribosomal proteins. Among these factors, three Brix-domain proteins and their binding partners form a ring-like structure at ribosomal RNA (rRNA) domain boundaries to support the architecture of the maturing particle. The existence of mutually exclusive conformations of these pre-60S particles suggests that the formation of the polypeptide exit tunnel is achieved through different folding pathways during subsequent stages of ribosome assembly. These structures rationalize previous genetic and biochemical data and highlight the mechanisms that drive eukaryotic ribosome assembly in a unidirectional manner.

The assembly of the large eukaryotic ribosomal subunit (60S) is organized as a series of consecutive intermediates, which are regulated by different sets of ribosome assembly factors in the nucleolus, nucleus and cytoplasm1. Three major types of pre-60S particles have been observed, each with a distinct composition of assembly factors, representing late nucleolar2, nuclear3 and late nucleo-cytoplasmic intermediates4. The earliest pre-60S particles exist in the nucleolus, where they undergo major RNA processing steps and conformational changes. Subsequently, in the nucleoplasm, the internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) RNA is removed and the particles are assembled into a nuclear-export-competent state. Exported particles then complete the final steps of maturation in the cytoplasm.

While previous high-resolution structural studies have revealed the architectures of the late nucleolar and export-competent pre-60S particles, the architecture of the early nucleolar particles, containing specific factors such as Nsa1, remains unknown2,4. Although the identities and approximate binding regions of many early nucleolar ribosome assembly factors are known, their structures and functions have not yet been determined5.

To elucidate the mechanisms that govern early nucleolar large-subunit assembly, several laboratories, including ours (data not shown), have observed that cellular starvation extends the lifetime of a 27SB prerRNA- containing species6,7. Here, we have isolated these intermediates from starved yeast using tandem-affinity purification involving tagged ribosome assembly factors Nsa1 and Nop2 (Extended Data Fig. 1). Similar to the small subunit processome, the nucleolar pre-60S particle, which is compositionally related to Nsa1-containing particles8, accumulates upon starvation. We analysed purified nucleolar pre-60S particles by cryo-EM, revealing a high-resolution core (3.4 Å) that was further sub-classified into three states, which we structurally resolved at resolutions of 4.3 Å (state 1), 3.7 Å (state 2) and 4.6 Å (state 3) (Table 1, Extended Data Figs 2, 3). These three states, together with cross-linking and mass spectrometry data, resulted in the identification of 21 ribosome assembly factors (Extended Data Table 1 and Supplementary Dataset 1). Atomic models could be completed for 18 of these proteins, and homology and poly-alanine models were used for proteins such as Ebp2, Mak11 and Ytm1, which were located in more flexible regions (Fig. 1, Extended Data Fig. 4).

Table 1.

Cryo-EM data collection parameters and refinement and validation statistics

| Core | State 2 EMD-7324 PDB 6C0F |

State 2A | State 3 EMD-7445 PDB 6CB1 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection and processing | ||||

| Magnification | 22,500× | |||

| Voltage (kV) | 300 | |||

| Pixel size (Å) | 1.3 | |||

| Electron exposure (e− Å−2) | 47 | |||

| Defocus range (µm) | 1.0–3.5 | |||

| Symmetry imposed | C1 | |||

| Initial particle images | 1,653,290 | |||

| Final particle images | 514,746 | 201,114 | 75,512 | 31,419 |

| Resolution (Å) | 3.4 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 4.6 |

| FSC threshold | 0.143 | |||

| Map sharpening B-factor (Å2) | −68.7 | −71.7 | −83.0 | −94.2 |

| Refinement | ||||

| Model composition | ||||

| Non hydrogen atoms | 91,741 | 69,945 | ||

| Protein residues | 7,197 | 6,347 | ||

| RNA bases | 1,602 | 1,615 | ||

| Ligands | 3 | 2 | ||

| r.m.s.d. | ||||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.007 | 0.006 | ||

| Angles (°) | 1.11 | 1.10 | ||

| Validation | ||||

| MolProbity score | 1.91 | 1.68 | ||

| Clashscore | 10.67 | 5.96 | ||

| Rotamer outliers (%) | 0.30 | 0.13 | ||

| Good sugar puckers (%) | 98 | 97 | ||

| Ramachandran | ||||

| Favoured (%) | 94.75 | 94.85 | ||

| Allowed (%) | 5.18 | 5.02 | ||

| Outliers (%) | 0.07 | 0.13 |

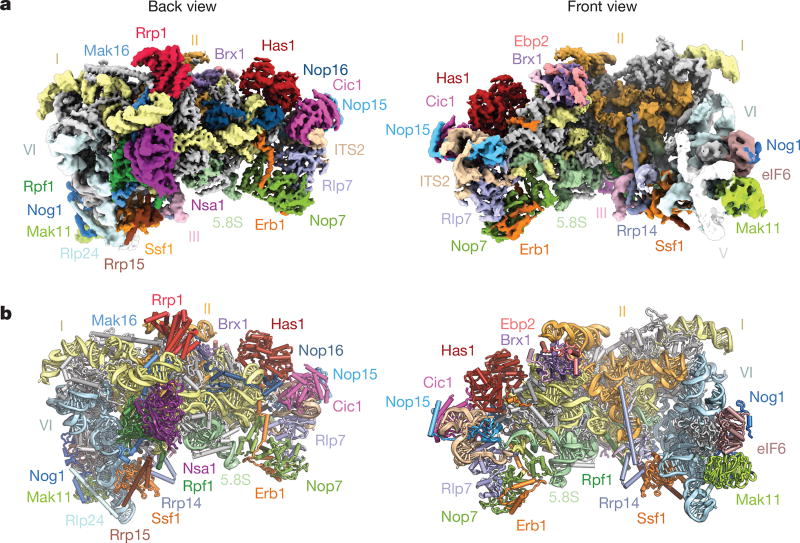

Figure 1. Structure of the early nucleolar pre-60S particle.

a, Composite cryo-EM density map of state 2, consisting of 25S rRNA domains I and II (3.4 Å) and VI (3.7 Å) (low-pass filtered to 5 Å), and associated proteins. b, Corresponding near-atomic model of state 2 with ribosome assembly factors and 25S rRNA domains labelled and colour-coded. Ribosomal proteins are shown in grey.

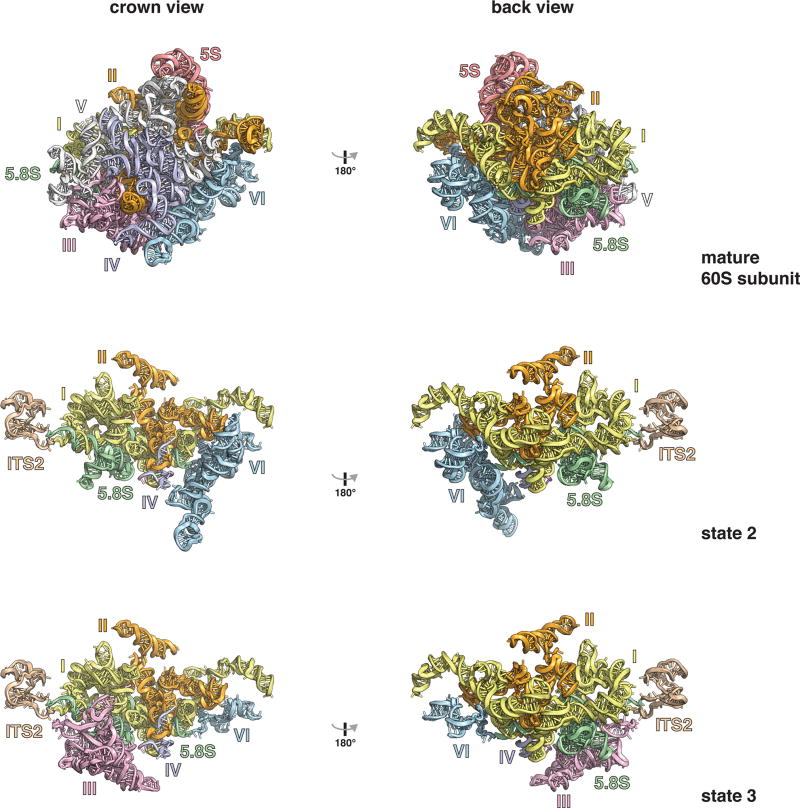

The purified pre-60S particles contain 27SB rRNA that has not yet been processed at ITS2 (Extended Data Fig. 1). We observed three different conformational states of this RNA (Extended Data Figs 2, 5). State 1 includes ordered density for ITS2, domains I and II, and the 5.8S rRNA. State 2 additionally revealed density for domain VI, which is present in a near-mature conformation. In contrast to state 2, state 3 lacks an ordered domain VI but features domain III. Although present, the majority of domains IV and V and the 5S ribonucleoprotein (RNP) were poorly resolved in all of the reconstructions, owing to conformational flexibility. Low-resolution features corresponding to parts of domain V (helices 74–79) and its proximal assembly factor Mak11 can be seen in states 2 and 2A (Fig. 1, Extended Data Fig. 2).

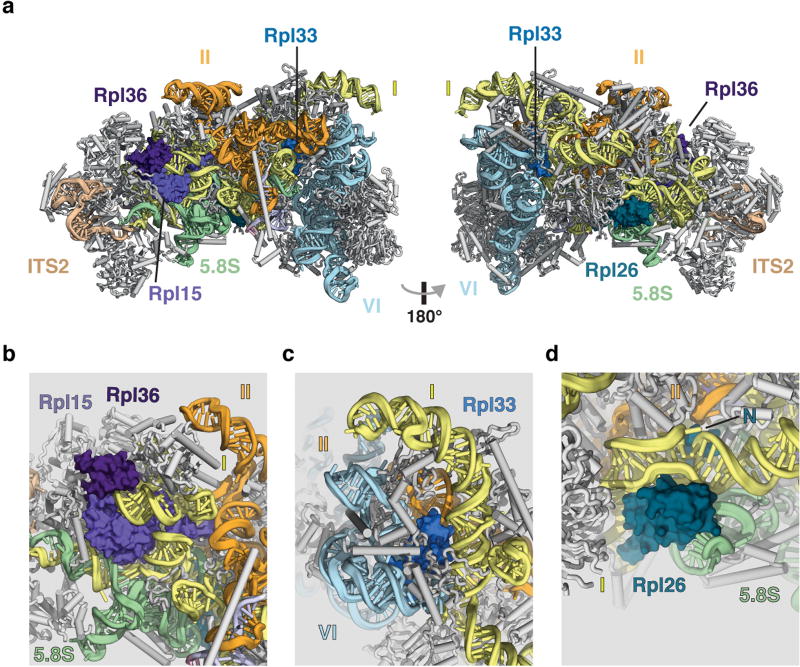

A striking feature of the nucleolar pre-60S particle is its open architecture, in which the solvent-exposed domains I, II and VI are encapsulated by a series of ribosome assembly factors as visualized in state 2 (Fig. 1, Extended Data Fig. 5, Supplementary Video). Notably, ribosomal proteins that have been associated with Diamond–Blackfan anaemia9 are located at critical rRNA domain interfaces in the structure (Extended Data Fig. 6), suggesting that their architectural roles are especially important during early nucleolar assembly, in which defects can trigger the nucleolar stress response.

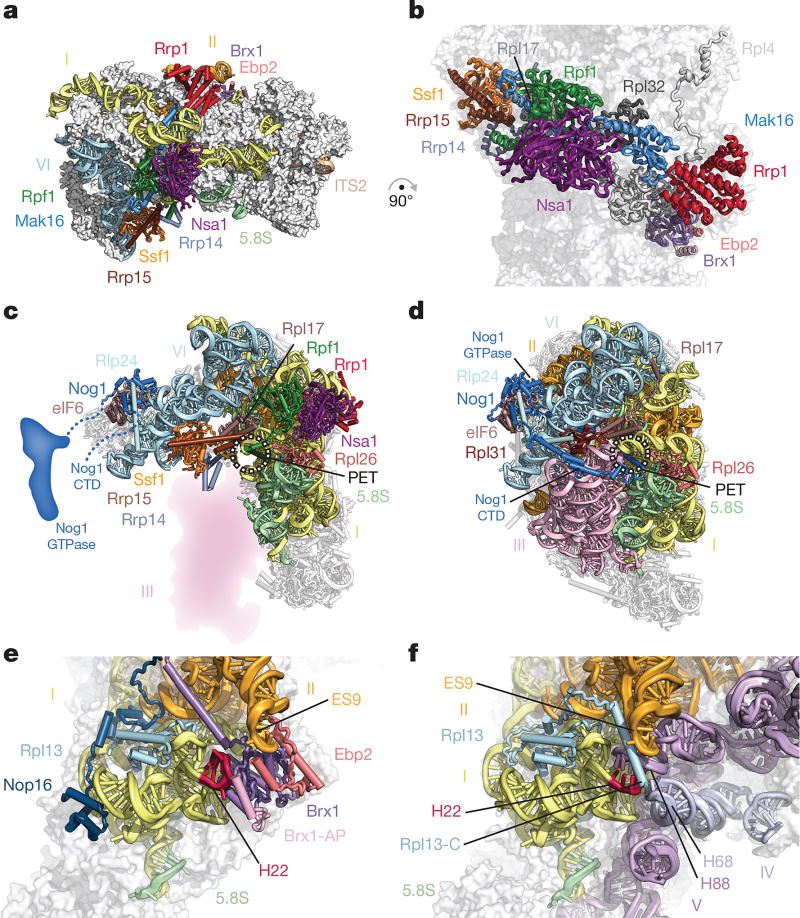

Domains I, II and VI adopt an open conformation that is chaperoned by eight early ribosome assembly factors, which form a ring-like structure at the solvent-exposed side (Fig. 2a). In particular, Brix-domain-containing factors (Brx1, Rpf1 and Ssf1) act in conjunction with their respective binding partners (Ebp2, Mak16 and Rrp15) to interconnect these junctions and sterically prevent premature RNA–protein and RNA–RNA contacts. Architectural support for the major interface between domains I and II is provided by Rpf1 and its zinc-binding interaction partner Mak16, the helical repeat protein Rrp1 and the beta-propeller Nsa1. Rpf1 and Nsa1 occupy a region near the domain I binding site of Rpl17, while Mak16 and Rrp1 interface predominantly with ribosomal proteins Rpl4 and Rpl32 within domain II (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2. A ring of nucleolar assembly factors prevents premature folding of the 25S rRNA.

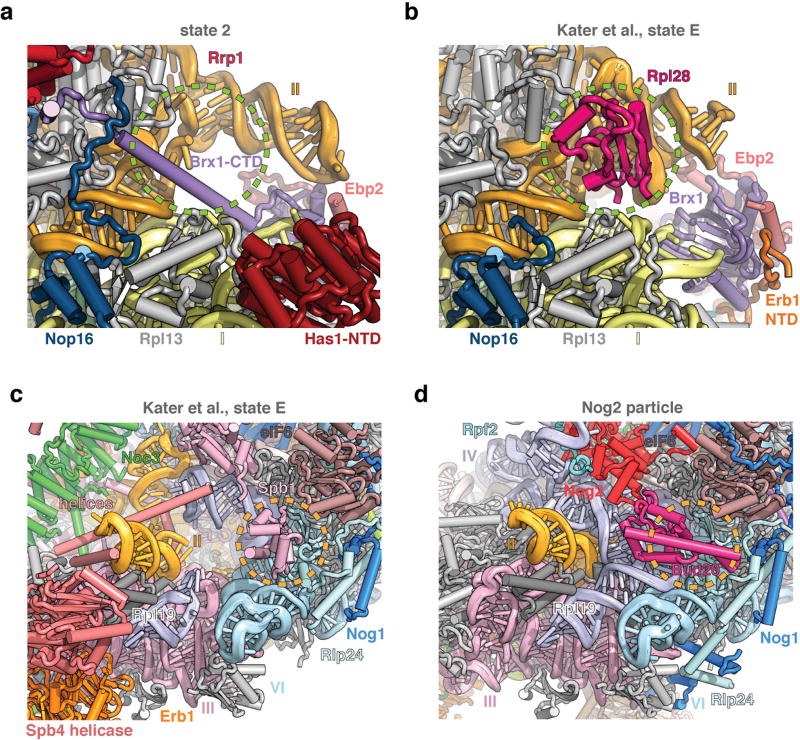

a, b, Assembly factors chaperone areas of domains I, II and VI and interact with ribosomal proteins. c, d, Assembly factors prevent the formation of the polypeptide exit tunnel (PET). c, In state 2, Ssf1–Rrp15 blocks the binding of Rpl31. Nog1 is largely unstructured. d, In the Nog2 particle (PDB 3JCT), the PET is formed, probed by Nog1 and supported by Rpl31. e, f, Brx1–Ebp2 and an associated peptide (Brx1-AP) remodel domain I (helix 22) to prevent binding of domain V (helix 88) and domain IV (helix 68) (e); these interactions are present in the Nog2 particle (f).

The ring-like structure encapsulating domains I, II and VI is continued in one direction by the Ssf1–Rrp15 heterodimer and Rrp14. While the long C-terminal helix of Rrp14 bridges domains II and VI, the Ssf1–Rrp15 complex is positioned at the interface of domains I and VI (Fig. 2a). Here, Ssf1 occupies the same position as Rpl31, which in the later Nog2-containing pre-60S particles binds at the interface of domains III and VI near the polypeptide exit tunnel (PET)2. The PET, which is created by domains I, III and VI at the solvent-exposed side, is already formed in the Nog2 particle, where it is blocked by the C-terminal domain (CTD) of the GTPase Nog1 (Fig. 2c, d).

The role of the Brx1–Ebp2 heterodimer near the interface of domains I and II is twofold. As well as being involved in the stabilization of these domains, its strategic binding site prevents the premature assembly of the large subunit by steric hindrance. In later stages of large subunit assembly, an RNA segment of domain I (helix 22) base-pairs with a region in domain V (helix 88) near a separate region of domain IV (helix 68) (Fig. 2e, f). Brx1 remodels helix 22 of domain I to block the premature formation of this tertiary structure with helix 88. Similarly, Brx1 prevents the mature conformations of domain IV (helix 68), domain II (expansion segment 9) and the C-terminal region of Rpl13 in this region (Fig. 2e, f).

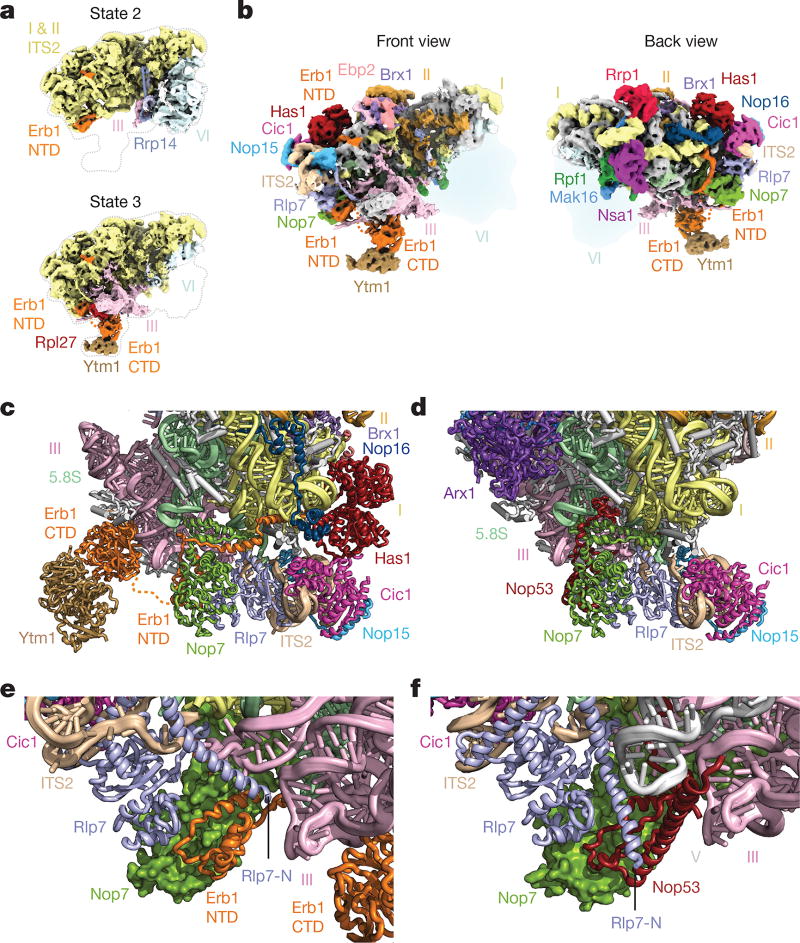

In state 3, we identified the Erb1–Ytm1 heterodimer bound to domain III via Rpl27 (Fig. 3a). The N-terminal region of Erb1 (residues 239–397) wraps around the entire ITS2–domain I interface and is positioned underneath Nop16 and Has1 (Fig. 3b, c). This location is consistent with previous cross-linking data and explains why deletions in this region prevent the incorporation of Erb1 into pre-60S particles10,11. Nop16 interconnects RNA elements of the 5.8S rRNA and regions of domain I. Additionally, Nop16 interacts with both Rpl8 and Rpl13 (Fig. 3c). The DEAD-box helicase Has1 is positioned at the interface of Rpl8, Cic1, Nop16 and Erb1 (Fig. 3c). The assembly factors Cic1, Rlp7, Nop7 and Nop15 appear in both the nucleolar pre-60S particle and the Nog2 particle in largely the same conformation (Fig. 3c, d).

Figure 3. Molecular mimicry by Erb1 prevents premature ITS2 processing.

a, Cryo-EM maps of states 2 and 3 of the nucleolar pre-60S particle. State 2 contains domain VI but limited density for domain III, while state 3 contains domain III with a flexible domain VI. NTD, N-terminal domain. b, Two views of the state 3 cryo-EM map. c, d, Cartoon representation of the ITS2 region in state 3 of the nucleolar pre-60S particle (c) and the Nog2 particle (PDB 3JCT) (d). e, f, The N termini of Erb1 and Rlp7 in the nucleolar pre-60S particle prevent the binding of Nop53 (e), which binds to Nop7 in the Nog2 particle (f).

Notably, the N-terminal segment of Erb1 employs molecular mimicry by binding to Nop7 in a similar fashion as Nop53 in the Nog2 particle, which uses a structurally related motif to bind to Nop7. The resulting steric hindrance is exacerbated by the alternate conformation of the N terminus of Rlp7, which further prevents Nop53 binding (Fig. 3e, f). Therefore, the coordinated mechanical removal of Erb1 and its proximal factors Ytm1, Nop16 and Has1 by Mdn1 is required before Nop53 can bind to the Nog2 particle and recruit the exosome-associated RNA helicase Mtr4 for ITS2 processing12,13. The Has1 helicase may have acted upon its substrate at an earlier stage during the 27SA3-to-27SB transition. Alternatively, it may remodel flexible RNA elements in its vicinity for the ensuing 27SB processing14.

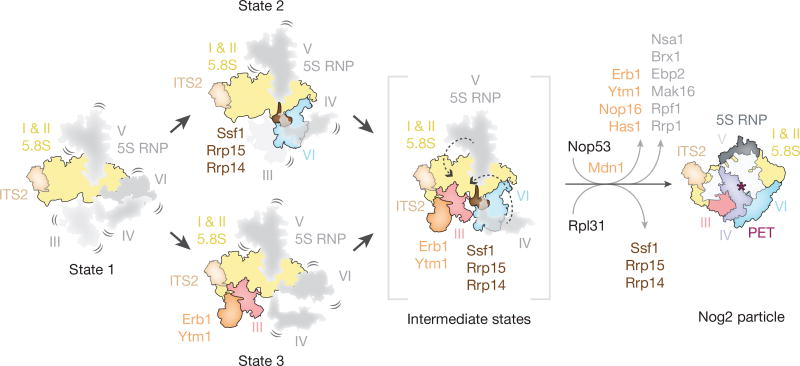

The nucleolar pre-60S states 2 and 3 represent distinct assembly intermediates of the polypeptide exit tunnel (Fig. 4). Ssf1, Rrp15 and Rrp14 are ordered in state 2, where they chaperone domains I and VI, which line two sides of the forming PET (Fig. 2b, c). By contrast, domain VI, Ssf1, Rrp15 and Rrp14 are disordered in state 3. Here, Ytm1 and Erb1 chaperone domain III, which adopts a mature conformation with respect to domain I to form a different intermediate of the PET (Fig. 3a, b). A subsequent maturation step of states 2 and 3 is likely to involve the joining of domains III and VI and the formation of the PET on the solvent-exposed side. This may be accompanied by the insertion of the Nog1 N terminus into the nascent PET and the replacement of Ssf1–Rrp15 by Rpl31 (Fig. 2c, d, 4).

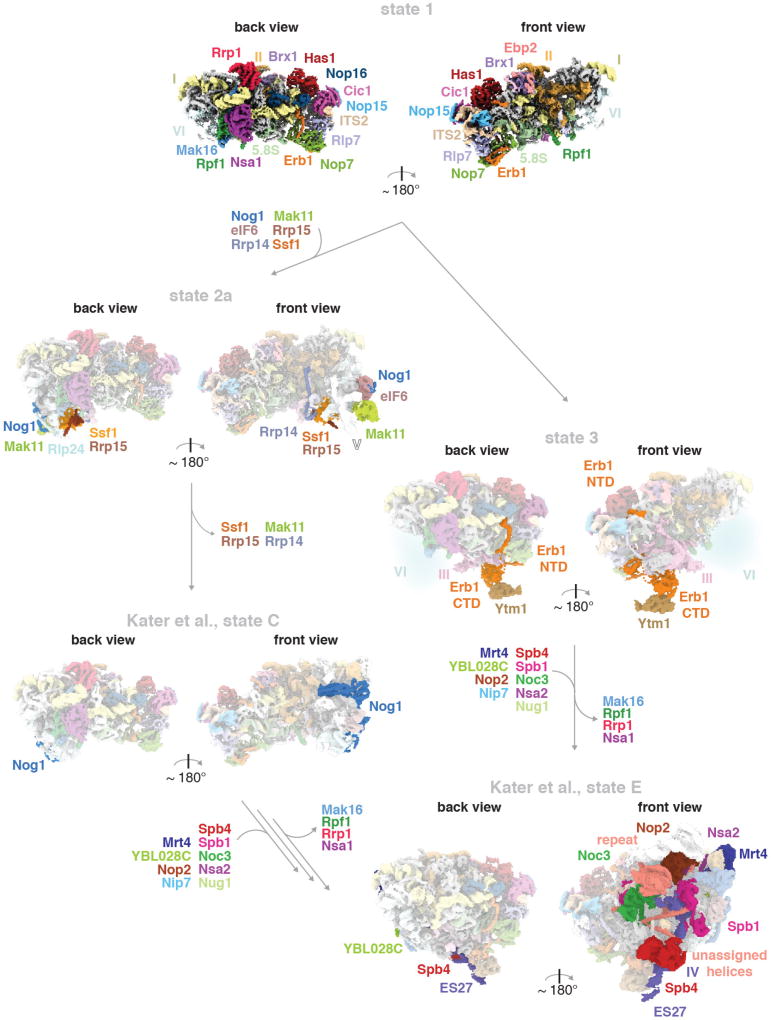

Figure 4. Model of early nucleolar stages of large subunit assembly.

Domains of 25S rRNA are represented as separate segments that are flexible (in grey) or stably incorporated (in colour). State 1 represents an intermediate in which domains I and II are ordered and subsequent folding of either domain III or VI will occur (state 3 and state 2, respectively) to partially form the polypeptide exit tunnel (PET). To mature into the Nog2 particle, the formation of the nascent PET must occur by Mdn1- and Rix7-dependent exchange and removal of assembly factors alongside stepwise folding of domain V and then domain IV.

Conformational changes, first by the initially flexible domain V–5S RNP together with the Nog1 GTPase domain, and subsequently by domain IV, would result in the overall conformation observed in the late-nucleolar Nog2 particle2 (Fig. 2c, d, 4). The base-pairing between domains I and V would be possible upon the dissociation of the Brx1– Ebp2 complex (Fig. 2e, f), while the release of Rrp1, Rpf1 and Mak16 is likely to be caused by the ATPase Rix7 acting on the proximal Nsa1 (ref. 15). In the ITS2 region, Mdn1-dependent removal of Erb1–Ytm1 would expose the binding site of Nop53 and may also trigger the exit of Nop16 and Has1 from the particle13.

While this manuscript was under review, complementary structural data on the nucleolar assembly of the large ribosomal subunit was published16. Differences in purification conditions resulted in the isolation of distinct states, which may represent assembly stages or breakdown products. Together with our data, these results enable visualization of early nucleolar pre-60S intermediates, from the formation of the solvent-exposed side of the particle to the incorporation of the DEAD-box helicase Spb4 at the subunit interface (Extended Data Fig. 7). Throughout the assembly, proteins such as Erb1, Brx1 and subsequently Spb1 prevent premature association of later maturation factors by steric hindrance (Extended Data Fig. 8). Additionally, flexible elements of Ebp2 and Erb1 reduce conformational freedom of the maturing particles.

Eukaryotic nucleolar 60S ribosome assembly is conceptually reminiscent of early prokaryotic 50S assembly intermediates in which different rRNA domains are assembled in a modular fashion17 (Fig. 4, Extended Data Fig. 7). However, our structures of nucleolar pre-60S particles highlight the high degree of control that is exerted to prevent the premature formation of inter-domain contacts of ribosomal RNA. They further illustrate how the reduction of conformational freedom and ordered sequence of assembly factors are enforced during assembly. These are overarching themes of the nucleolar stages for both the small and large ribosomal subunit assembly18.

Online Content Methods, along with any additional Extended Data display items and Source Data, are available in the online version of the paper; references unique to these sections appear only in the online paper.

Methods

Purification of nucleolar pre-60S particles

Nucleolar pre-60S particles were purified from a Saccharomyces cerevisiae BY4741 strain containing a TEV protease- cleavable C-terminal GFP tag on Nsa1 (Nsa1–40aaLinker–TEV–GFP) and a C-terminal 5× beta-catenin 3C protease-cleavable tag on Nop2 (Nop2– 40aaLinker–3C–Bc5) for endogenous expression. Cultures were grown in full synthetic drop-out (SD) medium containing 2% raffinose (w/v) at 30 °C to an optical density of 0.8–1, before addition of 2% galactose (w/v) for 16 h, reaching saturation (optical density 5–6). Cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 3,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. The cell pellet was washed with ice-cold ddH2O twice, followed by a wash with ddH2O containing protease inhibitors (E64, pepstatin and PMSF). Washed cells were immediately flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and lysed by four cycles of cryogenic grinding using a Retsch Planetary Ball Mill PM100.

The freshly ground yeast powder was resuspended by vortexing in buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6 (20 °C), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% Triton-X100, PMSF, pepstatin, E-64). The insoluble fraction was removed by centrifugation at 4 °C, 40,000g for 30 min. The supernatant was subsequently incubated with anti-GFP nanobody beads (Chromotek) for 3 h at 4 °C, with agitation. The beads were washed four times in ice-cold buffer A before the bound proteins were eluted using TEV-protease cleavage (1 h, 4 °C). The eluate was then incubated with NHS–sepharose beads (Sigma) coupled with anti-beta-catenin nanobody19 in buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6 (20 °C), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT) for 1 h at 4 °C with agitation. For electron microscopy sample preparation, the anti-beta catenin beads were washed once with buffer B. Cleavage by 3C protease for 1 h at 4 °C released the Nsa1–Nop2 containing nucleolar pre-60S particles. For protein–protein cross-linking analysis the eluate from GFP-nanobody beads was incubated with beta catenin-nanobody beads in buffer C (50 mM HEPES-NaOH pH 7.6 (4 °C), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) and eluted in the same buffer by 3C-protease cleavage. The eluate typically measured an absorbance at 260 nm (A260) of 2.4–4.5 milli absorbance units (mAU) (Nanodrop 2000, Thermo Scientific) (Extended Data Fig. 1).

Cryo-EM sample and grid preparation

Cryo-EM grids were prepared on four different occasions for the four datasets obtained (ds1–ds4). The nucleolar pre-60S particle eluate in sample buffer B (above) was left as is (ds1 only), or supplemented with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 5 mM MgCl2 (final concentration, ds2–ds4). Copper grids of 400 mesh with lacey carbon and an ultra-thin carbon support film were used (Ted Pella, product no. 01824) for data collection. A volume of 3–4 µl nucleolar pre-60S particle sample (absorbance at 260 nm of 2.5 mAU) was applied onto glow-discharged grids and plunged into liquid ethane using a Vitrobot Mark IV robot (FEI Company) (100% humidity, blot force of 0 and blot time 3.5–4 s).

Cryo-EM data collection and image processing

A total of 14,201 micrographs were obtained over four data collections (ds1–ds4) on a Titan Krios (FEI Company) at 300 kV with a K2 Summit detector (Gatan). SerialEM20 was employed for data acquisition using a defocus range of 1.0–3.5 µm with a pixel size of 1.3 Å. Super-resolution movies with 32 frames were collected using a total dose of 10 electrons per pixel per second with an exposure time of 8 s and a total dose of 47 electrons per Å2 (Table 1).

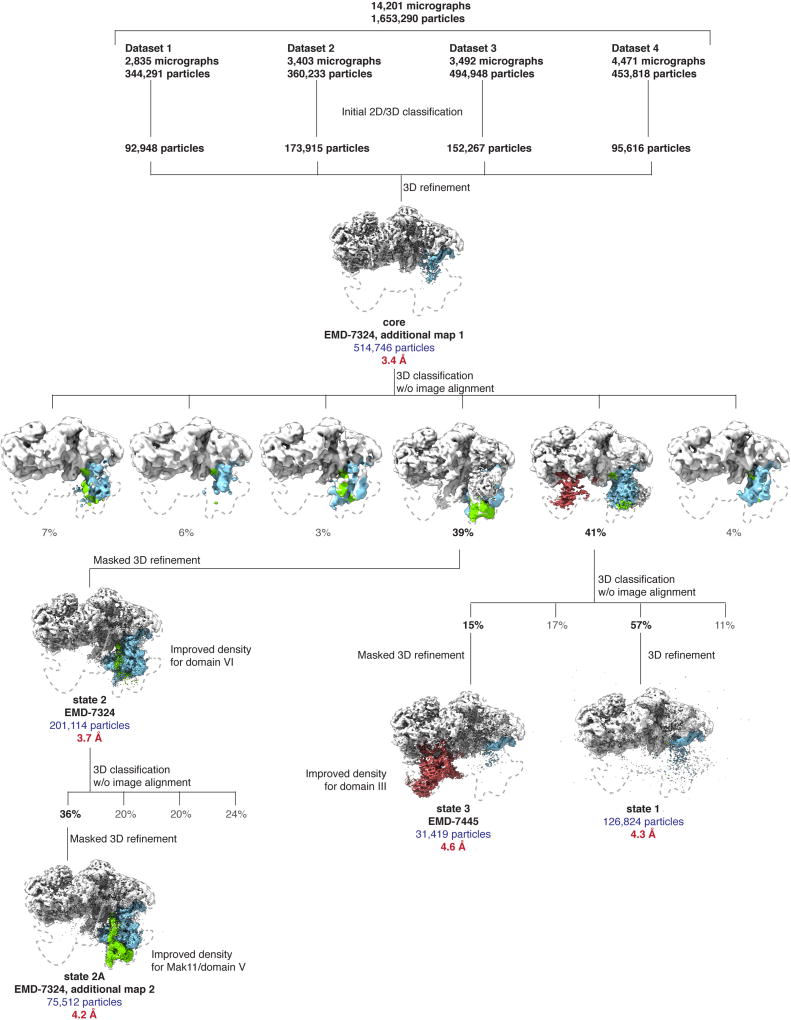

Upon data collection, the movies were gain corrected, dose weighted and aligned with Motioncor2 (ref. 21), and the contrast transfer function (CTF) was estimated using CTFFIND 4.1.5 (ref. 22). Relion 2.1 (ref. 23) was used for all subsequent particle picking, classifications and refinements. Corrected and aligned micrographs were first subjected to autopicking in Relion, resulting in a total of 1,653,290 selected particles from all four datasets. After manual inspection of all micrographs, particles were extracted with a box size of 480 pixels (2× -binned to 240 pixels), and 2D-classified separately for each individual dataset. After 2D classification, bad classes were removed, and the selected particles of each dataset were 3D-classified into four classes using an initial 3D model obtained from cryoSPARC24, low-pass filtered to 60 Å. The best one-to-two classes from each 3D classification were selected and their particles were re-extracted with a box size of 480 pixels (un-binned). A combined total of 514,746 particles was finally used for 3D auto-refinement and post-processing with a solvent mask around a ‘core’ containing domains I and II of the 25S rRNA, resulting in an overall resolution of 3.4 Å (Extended Data Figs 2, 3a). Since the more flexible domains III–VI were not visible in this state owing to averaging of different populations, a subsequent round of 3D classification without image alignment of these particles into six classes was used to obtain the two classes that contained state 2 (39%) and states 1 and 3 (41%). A refinement of the class containing state 2 (201,114 particles) was performed using a mask to include the additional visible densities, comprising of domain VI and its associated proteins, to obtain a final map at 3.7 Å (Extended Data Figs 2, 3b). By performing an additional round of focused 3D classification without image alignment on this class with a mask around Mak11 and the neighbouring segment of domain V of the 25S rRNA, a subset of particles (36%) emerged with improved density. This was refined to provide a more continuous map of Mak11 and domain V (state 2A) (Extended Data Figs 2, 3c). The remaining 64% of particles did not reveal additional features beyond those seen in state 2.

Owing to particle heterogeneity in the initial class containing states 1 and 3 (41%, 211,534 particles), a focused classification without image alignment of that class of particles was performed using a mask around the additional density containing domain III of the 25S rRNA, Erb1-CTD (WD40) and Ytm1 (WD40). The class from this round of classification containing density for domain III (31,419 particles) was refined with a mask around the entirety of state 3, to obtain a final map at 4.6 Å resolution (Extended Data Figs 2, 3d). The highest-resolution class of particles from this classification, which contained no density for domain III (126,824 particles), was refined to obtain the 4.3 Å map of state 1. The map of state 1 closely resembles the higher-resolution core map (correlation coefficient = 0.96). The local resolutions of the maps were calculated using Resmap25 (Extended Data Fig. 3).

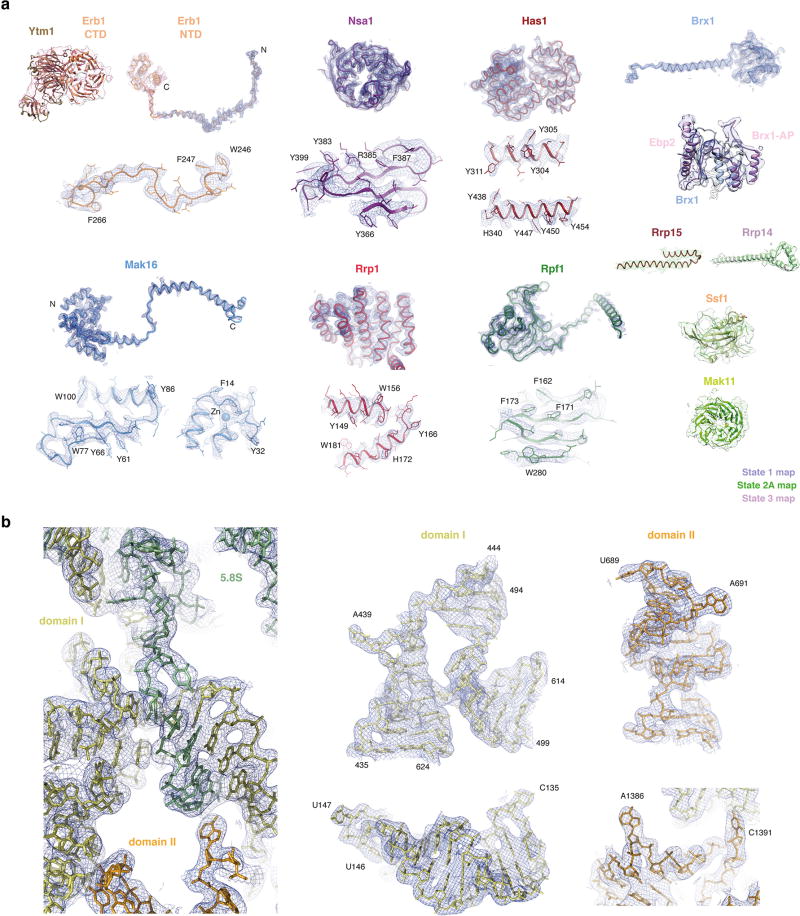

Model building and refinement

By using the structure of the late nucleolar pre-60S particle—the Nog2 particle (PDB 3JCT)2—as reference, common assembly factors and ribosomal proteins were manually located and fitted into the density, using Cic1 and Rpl7 as hallmark anchors. Protein identification and tracing were aided by cross-linking and mass spectrometry analyses (described below). New assembly factors Mak16, Rrp1, Nop16, Erb1-NTD, Rrp14, Rrp15 and Ebp2 and segments of rRNA were modelled de novo. Previously determined crystal structures of assembly factors Nsa1 (PDB 5SUI)26, Ytm1 (PDB 5CXB) and Erb1-CTD (PDB 4U7A)27 were docked and manually adjusted. Has1, Ssf1, Brx1, Rpf1 and Mak11 were initially docked from Phyre2 models28, and manually built to fit the density. Model building was performed with Coot29. An annotated list of individual protein IDs, reference models and corresponding maps used for building can be found in Extended Data Table 1. The model was refined against a half-map1 from the overall 3.7 Å map of state 2 in PHENIX with phenix.real_space_refine using secondary structure restraints for proteins and RNAs30. Refinement and model statistics can be found in Table 1.

Map and model visualization

All map and model analyses and illustrations were made using Chimera31 and PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, v.1.8 (Schrödinger). Density map visualization for certain figures was also performed on UCSF ChimeraX, developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics and the University of California, San Francisco (supported by NIGMS P41-GM103311).

RNA extraction and northern blotting

The S. cerevisiae nucleolar pre-60S particle (Nsa1–Nop2 particle) was purified as described in ‘Purification of nucleolar pre-60S particles’ and RNA was extracted from the final 3C-protease elution with 1 ml TRIzol (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Isolated nucleolar pre-60S RNA (1.0 µg) was separated on a denaturing 1.2% formaldehyde–agarose gel (SeaKem LE, Lonza) or on a denaturing 10% urea–PAGE (Fisher, Amresco) for the 5S rRNA northern blot. After staining the gel in 1× SYBR Green II (Lonza) ddH2O solution (pH 7.5) for 30 min, RNA species were visualized with a Gel Doc EZ Imager (Bio-Rad) (Extended Data Fig. 1d, e) and then transferred onto a cationized nylon membrane (Zeta-Probe GT, Bio-Rad) using downward capillary transfer for the agarose gel and a Trans-Blot SD semi-dry transfer cell (Bio-Rad) for the urea–PAGE gel. RNA was cross-linked to the membrane for northern blot analysis by UV irradiation at 254 nm with a total exposure of 120 mJ/cm2 in a UV Stratalinker 2400 (Stratagene). Cross-linked membranes were incubated with hybridization buffer (750 mM NaCl, 75 mM trisodium citrate, 1% (w/v) SDS, 10% (w/v) dextran sulphate, 25% (v/v) formamide) at 65 °C for 30 min before addition of γ-32P-end-labelled DNA oligonucleotide probes. Oligonucleotide probe sequences were as follows: 25S, TTTCACTCTCTTTTCAAAGTTCTTTTCATCT; ITS1 3′ end, TT AATATTTTAAAATTTCCAG; ITS2 C2 site, TGGTAAAACCTAAAACGACCGT; 3′ -ETS 5′ end, CCACTTAGAAAGAAATAAAAA; and 5S, CTACTCGGTCAGGCTC.

Probes were hybridized for 1 h at 65 °C and then overnight at 37 °C. Membranes were washed once with wash buffer 1 (300 mM NaCl, 30 mM trisodium citrate, 1% (w/v) SDS) and once with wash buffer 2 (30 mM NaCl, 3 mM trisodium citrate, 1% (w/v) SDS) for 20 min each at 45 °C. Radioactive signal was detected by exposure of the washed membranes to a storage phosphor screen which was scanned with a Typhoon 9400 variable-mode imager (GE Healthcare). For northern blot source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1.

DSS cross-linking sample preparation and mass spectrometry analysis

The tandem-affinity purified nucleolar pre-60S particles (Nsa1–Nog2 particle), eluted off anti-beta catenin nanobody beads (in 50 mM HEPES–NaOH pH 7.6 (4 °C), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT) at an absorbance of 1.0 at 260 nm (Nanodrop 2000, Thermo Scientific), were pooled (total volume, 300 µl) and split into three 100-µl cross-linking reaction aliquots.

Disuccinimidylsuberate (DSS; 25 mM in DMSO, Creative Molecules) was added to each aliquot to yield a final DSS concentration of 2.0 mM and samples were cross-linked for 30 min at 25 °C with 450 r.p.m. constant mixing. The reactions were quenched with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (final concentration) and precipitated by adding methanol (Alfa Aesar, LC–MS grade) to a final concentration of 90% followed by incubation at −80 °C overnight. Precipitated cross-linked nucleolar pre-60S particles were combined into one tube by repeated centrifugation at 21,000g, 4 °C for 30 min. The resulting pellet was washed three times with 1 ml ice-cold 90% methanol, air-dried and finally resuspended in 50 µl 1× NuPAGE LDS buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

DSS cross-linked samples were processed as in ref. 18, and as described below. DSS cross-linked nucleolar pre-60S particles in LDS buffer were reduced with 25 mM DTT, alkylated with 100 mM 2-chloroacetamide, separated by SDS–PAGE in three lanes of a 3–8% tris-acetate gel (NuPAGE, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and stained with Coomassie blue. The gel region corresponding to cross-linked complexes was sliced and digested overnight with trypsin to generate cross-linked peptides. After digestion, the peptide mixture was acidified and extracted from the gel as previously described32,33. Peptides were fractionated offline by high-pH reverse-phase chromatography, loaded onto an EASY-Spray column (Thermo Fisher Scientific ES800: 15 cm × 75 µm ID, PepMap C18, 3 µm) via an EASY-nLC 1000, and gradient-eluted for online electrospray ionization–mass spectrometry (ESI–MS) and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analyses with a Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). MS/MS analyses of the top 8 precursors in each full scan used the following parameters: resolution, 17,500 (at 200 Th); AGC target, 2 × 105; maximum injection time, 800 ms; isolation width, 1.4 m/z; normalized collision energy, 24%; charge, 3–7; intensity threshold, 2.5 × 103; peptide match, off; dynamic exclusion tolerance, 1,500 mmu. Cross-linked peptides were identified from mass spectra by pLink34. All spectra reported here were manually verified as described previously32.

Data availability

Cryo-EM density maps for the yeast nucleolar pre-60S particle states 2 and 3 have been deposited in the EM Data Bank with accession codes EMD-7324 and EMD-7445, respectively. Atomic coordinates for the yeast nucleolar pre-60S particle states 2 and 3 have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 6C0F and 6CB1, respectively. A PyMOL session for the analysis of the yeast nucleolar pre-60S particle in state 2 is available in Supplementary Dataset 2.

Extended Data

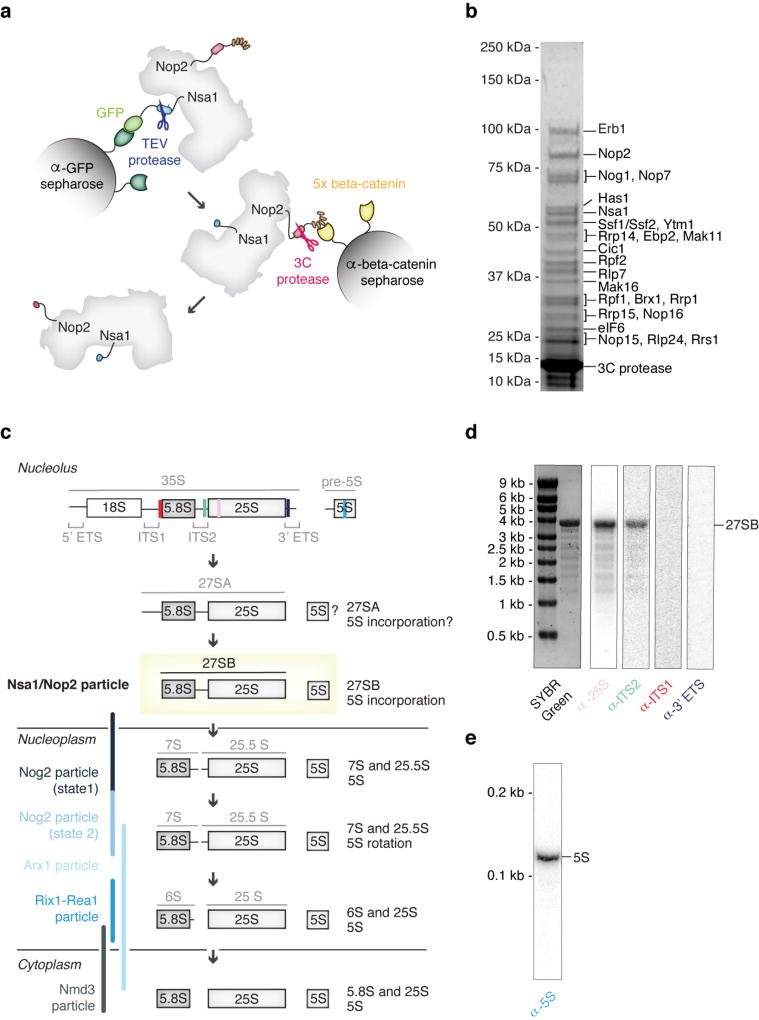

Extended Data Figure 1. Purification of tagged Nsa1–Nop2 nucleolar pre-60S particles and analysis of RNA components.

a, Schematic of tandem-affinity purification of the nucleolar pre-60S particle with tagged proteins Nsa1 and Nop2. b, Coomassie-blue stained SDS–PAGE of pre-60S particles purified as in a. Protein labels are based on in-solution mass spectrometry analysis of purified pre-60S particles and the approximate molecular weight. c, Schematic processing of the large ribosomal subunit rRNAs in yeast. The locations of the previously published pre-60S particles (the Nog2 particles2, the Arx1 particle35, the Rix1–Rea1 particle3 and the Nmd3 particle4) are represented by blue bars. Binding sites of northern blot probes are indicated on the 35S and pre-5S transcript. d, e, Pre-rRNA was visualized on an agarose gel and stained using SYBR Green II. Northern blot analysis was performed for the 25S, ITS2, ITS1 and 3′ ETS RNAs (d) and for the 5S rRNA (e).

Extended Data Figure 2. Cryo-EM data-processing workflow.

Four data collections were performed, resulting in 14,201 micrographs. These micrographs were aligned using MotionCor2 (ref. 21) with dose weighting, and imported into Relion2.1 (ref. 23) for further processing. Autopicking followed by manual cleaning, 2D and 3D classification produced a total of 514,746 ‘good’ particles. These particles were refined to produce the core map. Further 3D classification without and with alignment was used to obtain the state 1, state 2, state 2A and state 3 maps. Density regions corresponding to domain III (red), domain VI (blue) and Mak11 (green) are highlighted.

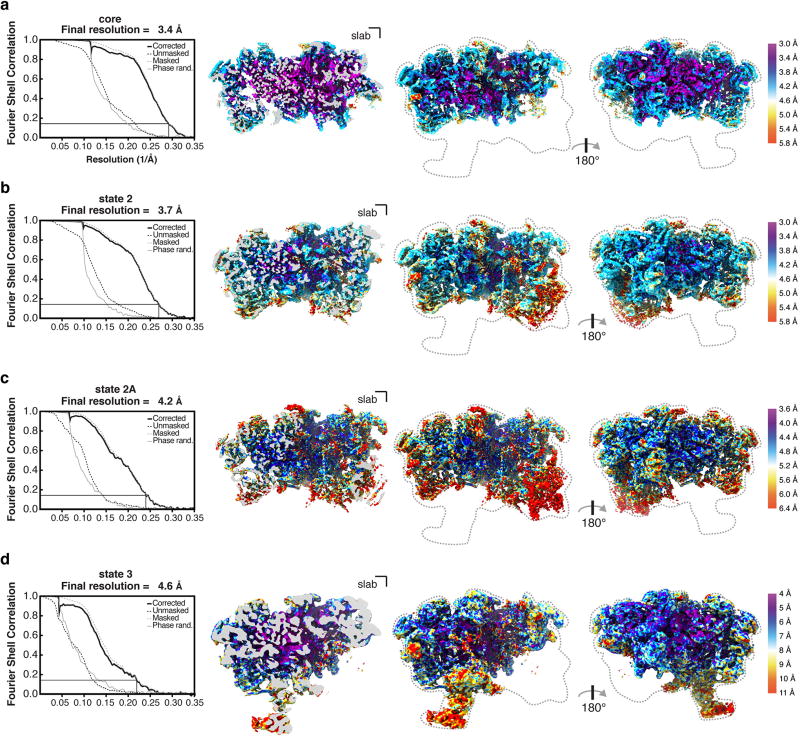

Extended Data Figure 3. Overall and local resolution estimates for core, state 2 and state 3 cryo-EM maps.

a–d, Overall and local resolution of core map at 3.4 Å (a), state 2 map at 3.7 Å (b), state 2A map with additional density for Mak11 at 4.2 Å (c) and state 3 map at 4.6 Å (d). Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) curves for the unmasked (dashed black line), phase-randomized (solid grey line), masked (dashed grey line) and the corrected map (solid black line) are also shown. A thin black line indicates an FSC value of 0.143. A clipped view is shown next to two views of the obtained cryo-EM maps. The density volumes are coloured according to local resolution using Resmap25.

Extended Data Figure 4. Cryo-EM density fit of selected nucleolar pre-60S ribosomal subunit proteins and RNA models.

a, Near-atomic models of assembly factors and their cryo-EM density. b, Selected regions of the 25S rRNA and 5.8S rRNA models and their cryo-EM density. Images generated in PyMOL or Chimera.

Extended Data Figure 5. rRNA domains of state 2, state 3 and the mature 60S ribosomal subunit.

The 5.8S rRNA, the 5S rRNA and the domains of the 25S rRNA are colour-coded and displayed in the crown and back view for each structure.

Extended Data Figure 6. Ribosomal proteins associated with Diamond–Blackfan anaemia are positioned at rRNA domain junctions in the nucleolar pre-60S particle.

a, Two views of the nucleolar pre-60S particle state 2 model, with Diamond–Blackfan anaemia-associated ribosomal proteins shown in surface representation. b, Rpl15 is located between the 5.8S-domain I duplex and a domain I–domain II interface. c, Rpl33 (Rpl35 in Homo sapiens) binds at the junction of domains I, II and VI in the 25S rRNA. d, Rpl26 associates with the domain I–5.8S rRNA interface and additionally inserts its N terminus (N) between domain I and domain II.

Extended Data Figure 7. Intermediates of nucleolar pre-60S assembly.

The structural data presented in this paper (states 1, 2, and 3) are complemented by recent data on pre-60S assembly: states C (EMD-3893) and E (EMD-3891)16. State 1 is highly similar to state A (EMD-3888)16. States 2 and 2A correspond closely to state B (EMD-3889)16, but state B lacks the Ssf1–Rrp15–Rrp14 module and Mak11. Built assembly factors that become ordered or leave in subsequent particles are indicated with arrows. Two possible pathways are shown that result in the final incorporation of the DEAD-box helicase Spb4 (previously unidentified16).

Extended Data Figure 8. Steric hindrance during nucleolar pre-60S assembly.

a, b, Comparative views of state 2 (a) and state E (PDB 6ELZ)16 (b), highlighting that the binding of the Brx1 CTD to Rrp1 prevents premature incorporation of Rpl28. c, d, Comparative views of state E (c) and the Nog2 particle (PDB 3JCT) (d), highlighting that the presence of Spb1 prevents the binding of Bud20.

Extended Data Table 1.

Molecular models of the nucleolar pre-60S ribosomal subunit

| Subgroup | Chain ID | SegID | Molecule name |

Total residues or bases |

Modelled (residue range) |

Initial PDB template |

Present in… |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA | 1 | L1 | 25S | 3,396 | atomic (1,676 bases) | 3JCT | All states |

| 2 | L2 | 5.8S | 158 | atomic (158 bases) | 3JCT | All states | |

| 6 | L6 | ITS2 | 232 | atomic (87 bases) | 3JCT | All states | |

| Ribosomal proteins | C | LC | Rpl4A_uL4 | 362 | atomic (2–56, 89–347) | 3JCT | All states |

| E | LE | Rpl6A_eL6 | 176 | atomic (7–176) | 3JCT | All states | |

| e | SE | Rpl32_eL32 | 130 | atomic (7–36, 47–130) | 3JCT | All states | |

| F | LF | Rpl7A_uL30 | 244 | atomic (3–244) | 3JCT | All states | |

| f | SF | Rpl33A_eL33 | 107 | atomic (2–107) | 3JCT | All states | |

| G | LG | Rpl8A_eL8 | 256 | atomic (53–239) | 3JCT | All states | |

| h | SH | Rpl35A_uL29 | 120 | atomic (2–120) | 3JCT | All states | |

| i | SI | Rpl36A_eL36 | 100 | atomic (17–100) | 3JCT | All states | |

| L | LL | Rpl13A_eL13 | 199 | atomic (22–127) | 3JCT | All states | |

| M | LM | Rpl14A_eL14 | 138 | atomic (11–138) | 3JCT | All states | |

| N | LN | Rpl15A_eL15 | 204 | atomic (2–68, 96–204) | 3JCT | All states | |

| O | LO | Rpl16A_uL13 | 199 | atomic (3–59, 73–199) | 3JCT | All states | |

| Q | LQ | Rpl18A_eL18 | 186 | atomic (15–146) | 4v88, chain BQ | All states | |

| S | LS | Rpl20A_eL20 | 172 | atomic (2–172) | 3JCT | All states | |

| B | LB | Rpl3_uL3 | 387 | atomic (17–224, 270–385) | 4v88, chain DB | State 2 | |

| P | LP | Rpl17A_uL22 | 184 | atomic (10–64, 80–126, 140–161) | 3JCT | All states | |

| V | LV | Rpl23A_uL14 | 137 | atomic (16–137) | 3JCT | State 2 | |

| Y | LY | Rpl26A_uL24 | 127 | atomic (2–127) | 3JCT | All states | |

| j | SJ | Rpl37A_eL37 | 88 | atomic (14–85, Zn) | 3JCT | All states | |

| Z | LZ | Rpl27A_eL27 | 136 | side-chain trimmed (2–136) | 3JCT | State 3 | |

| k | SK | Rpl38_eL38 | 78 | side-chain trimmed (2–78) | 3JCT | State 3 | |

| g | SG | Rpl34A_eL34 | 121 | side-chain trimmed (2–102) | 3JCT | State 3 | |

| c | SC | Rpl30_eL30 | 105 | side-chain trimmed (9–105) | 3JCT | State 3 | |

| X | LX | Rpl25_uL23 | 142 | side-chain trimmed (2–142) | 3JCT | State 3 | |

| Assembly factors common to Nog2 particle (3JCT) | K | LK | Cic1 | 376 | atomic (31–51, 64–302) | 3JCT | All states |

| n | SN | Nop7 | 605 | atomic (13–43, 61–267, 351–396, 404–460) | 3JCT | All states | |

| o | SO | Nop15 | 220 | atomic (88–220) | 3JCT | All states | |

| t | ST | Rlp7 | 322 | atomic (54–105, 127–322) | 3JCT | All states | |

| t | ST | Rlp7 (NTD) | 322 | poly-alanine (20–53) | De novo | State 3 | |

| u | SU | Rlp24 | 199 | atomic (2–130, Zn) | 3JCT | State 2 | |

| y | SY | Tif6 | 245 | atomic (1–226) | 3JCT | State 2 | |

| W | LW | Nog1 | 647 | atomic (373–470) | 3JCT | State 2 | |

| New assembly factors | A | LA | Nsa1 | 463 | atomic (1–78, 101–416) | 5SUI | All states |

| p | SP | Has1 | 505 | atomic (42–252, 264–489) | Phyre model based on 2V1X | All states | |

| b | SB | Brx1 | 291 | atomic (31–122, 132–164, 174–192, 211–290), poly-alanine (123–131, 165–173) | Model based on 5WLC, chain SM | All states | |

| m | SM | Ebp2 | 427 | poly-alanine (196–269) | De novo | All states | |

| z | sz | Rrp1 | 278 | atomic (1–186, 197–253) | De novo | All states | |

| D | LD | Mak16 | 306 | atomic (2–191, Zn) | De novo | All states | |

| I | LI | Rpf1 | 295 | atomic (8–295) | Phyre model based on 5JPQ, chain c | All states | |

| s | SS | Erb1-NTD | 807 | atomic (239–298, 372–395), poly-alanine (299–371) | De novo | All states | |

| s | SS | Erb1-CTD | 807 | side-chain trimmed crystal structure (416–426, 428–534, 571–807) | 4U7A | State 3 | |

| v | SV | Ssf1 | 453 | atomic (23–214, 324–356) | Phyre model based on 4XV9 | State 2 | |

| q | SQ | Mak11 | 468 | poly-alanine (WD40, 285 residues) | Phyre model based on 3DM0 | States 2 and 2A | |

| w | SW | Rrp15 | 250 | atomic (174–243) | De novo | State 2 | |

| d | SD | Ytm1 | 460 | poly-alanine (C. thermophilum, 465 residues) | 5CXB | State 3 | |

| 7 | S7 | Nop16 | 231 | atomic (1–83, 156–228) | De novo | All states | |

| 8 | S8 | Rrp14 | 434 | atomic (296–393) | De novo | State 2 | |

| x | SX | Brx1-associated peptide | unknown | poly-alanine (162–189) | De novo | All states |

Individual protein chains are listed with their initial PDB template (or built de novo) and the nucleolar pre-60S particle state(s) in which they are present.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Ebrahim and J. Sotiris for their support with data collection at the Evelyn Gruss Lipper Cryo-EM resource center, M. Tesic-Mark for analysis of mass spectrometry data, C. Cheng for help with the initial manual curation and analysis of the nucleolar pre-60S particles and members of the Walz laboratory for helpful discussions. L.M. is supported in part by NIH T32 GM115327-Tan. J.B. is supported by an EMBO long-term fellowship (ALTF 51-2014) and a Swiss National Science Foundation fellowship (155515). M.C.-M. is supported by a postgraduate scholarship from NSERC. S.K. is supported by the Robertson Foundation, the Irma T. Hirschl Trust, the Alexandrine and Alexander L. Sinsheimer Fund, the Rita Allen Foundation and an NIH New Innovator Award (1DP2GM123459). B.T.C. is supported by National Institute of Health Grant Nos. P41GM103314 and P41GM109824.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper.

Author Contributions S.K. and Z.A.S. established purification conditions. Z.A.S., L.M. and S.K. determined the cryo-EM structure of the yeast nucleolar pre-60S particle. K.R.M., J.W. and B.T.C. processed and analysed DSS cross-linking data. Z.A.S., L.M., J.B., M.C.-M., M.H. and S.K. built the model. L.M. performed all RNA work, and Z.A.S., L.M., J.B., M.H., M.C.-M. and S.K. interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Konikkat S, Woolford JL., Jr Principles of 60S ribosomal subunit assembly emerging from recent studies in yeast. Biochem. J. 2017;474:195–214. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu S, et al. Diverse roles of assembly factors revealed by structures of late nuclear pre-60S ribosomes. Nature. 2016;534:133–137. doi: 10.1038/nature17942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrio-Garcia C, et al. Architecture of the Rix1–Rea1 checkpoint machinery during pre-60S-ribosome remodeling. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016;23:37–44. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma C, et al. Structural snapshot of cytoplasmic pre-60S ribosomal particles bound by Nmd3, Lsg1, Tif6 and Reh1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017;24:214–220. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen W, Xie Z, Yang F, Ye K. Stepwise assembly of the earliest precursors of large ribosomal subunits in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:6837–6847. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talkish J, et al. Disruption of ribosome assembly in yeast blocks cotranscriptional pre-rRNA processing and affects the global hierarchy of ribosome biogenesis. RNA. 2016;22:852–866. doi: 10.1261/rna.055780.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kos-Braun IC, Jung I, Koš M. Tor1 and CK2 kinases control a switch between alternative ribosome biogenesis pathways in a growth-dependent manner. PLoS Biol. 2017;15:e2000245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2000245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harnpicharnchai P, et al. Composition and functional characterization of yeast 66S ribosome assembly intermediates. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:505–515. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clinton C, Gazda HT. In: Diamond–Blackfan Anemia. Adam MP, et al., editors. University of Washington; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Granneman S, Petfalski E, Tollervey D. A cluster of ribosome synthesis factors regulate pre-rRNA folding and 5.8S rRNA maturation by the Rat1 exonuclease. EMBO J. 2011;30:4006–4019. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konikkat S, Biedka S, Woolford JL., Jr The assembly factor Erb1 functions in multiple remodeling events during 60S ribosomal subunit assembly in S. cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:4853–4865. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thoms M, et al. The exosome is recruited to RNA substrates through specific adaptor proteins. Cell. 2015;162:1029–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baßler J, et al. The AAA-ATPase Rea1 drives removal of biogenesis factors during multiple stages of 60S ribosome assembly. Mol. Cell. 2010;38:712–721. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dembowski JA, Kuo B, Woolford JL., Jr Has1 regulates consecutive maturation and processing steps for assembly of 60S ribosomal subunits. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:7889–7904. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kressler D, Roser D, Pertschy B, Hurt E. The AAA ATPase Rix7 powers progression of ribosome biogenesis by stripping Nsa1 from pre-60S particles. J. Cell Biol. 2008;181:935–944. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kater L, et al. Visualizing the assembly pathway of nucleolar pre-60S ribosomes. Cell. 2017;171:1599–1610.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis JH, et al. Modular assembly of the bacterial large ribosomal subunit. Cell. 2016;167:1610–1622.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barandun J, et al. The complete structure of the small-subunit processome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017;24:944–953. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun MB, et al. Peptides in headlock—a novel high-affinity and versatile peptide-binding nanobody for proteomics and microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:19211. doi: 10.1038/srep19211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mastronarde DN. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J. Struct. Biol. 2005;152:36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng SQ, et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:331–332. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rohou A, Grigorieff N. CTFFIND4: Fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J. Struct. Biol. 2015;192:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimanius D, Forsberg BO, Scheres SH, Lindahl E. Accelerated cryo-EM structure determination with parallelisation using GPUs in RELION-2. eLife. 2016;5:19. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ, Brubaker MA. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:290–296. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kucukelbir A, Sigworth FJ, Tagare HD. Quantifying the local resolution of cryo-EM density maps. Nat. Methods. 2014;11:63–65. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lo Y-H, Romes EM, Pillon MC, Sobhany M, Stanley RE. Structural analysis reveals features of ribosome assembly Factor Nsa1/WDR74 important for localization and interaction with Rix7/NVL2. Structure. 2017;25:762–772.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wegrecki M, Rodríguez-Galán O, de la Cruz J, Bravo J. The structure of Erb1–Ytm1 complex reveals the functional importance of a high-affinity binding between two β-propellers during the assembly of large ribosomal subunits in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:11017–11030. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJE. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi Y, et al. Structural characterization by cross-linking reveals the detailed architecture of a coatomer-related heptameric module from the nuclear pore complex. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2014;13:2927–2943. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.041673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi Y, et al. A strategy for dissecting the architectures of native macromolecular assemblies. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:1135–1138. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang B, et al. Identification of cross-linked peptides from complex samples. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:904–906. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bradatsch B, et al. Structure of the pre-60S ribosomal subunit with nuclear export factor Arx1 bound at the exit tunnel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:1234–1241. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Cryo-EM density maps for the yeast nucleolar pre-60S particle states 2 and 3 have been deposited in the EM Data Bank with accession codes EMD-7324 and EMD-7445, respectively. Atomic coordinates for the yeast nucleolar pre-60S particle states 2 and 3 have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 6C0F and 6CB1, respectively. A PyMOL session for the analysis of the yeast nucleolar pre-60S particle in state 2 is available in Supplementary Dataset 2.