Abstract

Background & objectives:

Legionella pneumophila, a ubiquitous aquatic organism is found to be associated with the development of the community as well as hospital-acquired pneumonia. Diagnosing Legionella infection is difficult unless supplemented with, diagnostic laboratory testing and established evidence for its presence in the hospital environment. Hence, the present study was undertaken to screen the hospital water supplies for the presence of L. pneumophila to show its presence in the hospital environment further facilitating early diagnosis and prevention of hospital-acquired legionellosis.

Methods:

Water samples and swabs from the inner side of the same water taps were collected from 30 distal water outlets present in patient care areas of a tertiary care hospital. The filtrate obtained from water samples as well as swabs were inoculated directly and after acid buffer treatment on plain and selective (with polymyxin B, cycloheximide and vancomycin) buffered charcoal yeast extract medium. The colonies grown were identified using standard methods and confirmed for L. pneumophila by latex agglutination test.

Results:

About 6.66 per cent (2/30) distal water outlets sampled were found to be contaminated with L. pneumophila serotype 2-15. Isolation was better with swabs compared to water samples.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The study showed the presence of L. pneumophila colonization of hospital water outlets at low levels. Periodic water sampling and active clinical surveillance in positive areas may be done to substantiate the evidence, to confirm or reject its role as a potential nosocomial pathogen in hospital environment.

Keywords: Environmental surveillance, hospital-acquired pneumonia, hospital water outlets, Legionella pneumophila

Legionella pneumophila is a ubiquitous bacterium commonly found in various natural and human-made aquatic environments. They can enter and multiply in hospital water systems in low or undetectable numbers and may result in the acquisition of infection by patients through aspiration of contaminated water or direct inhalation of aerosols. Water outlets, faucets, showers, humidifiers, respiratory devices and nebulizers that have been filled or cleaned with tap water have been reported as potential sources of infection in several cases1.

Establishing diagnosis of Legionella infection considering clinical criteria alone is difficult and warrants some index of suspicion and laboratory diagnosis2. This index of suspicion can be raised by generating knowledge about the possible presence of the organism in the hospital water supplies and outlets3. Legionella colonization of hospital water supplies in >30 per cent of the sampled water outlets merits initiation of specialized laboratory tests for Legionella screening in all patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia3. There are only a few studies on environmental colonization by Legionella from India4,5,6,7. Considering this, the present study was planned to identify potential environmental sources of Legionella species in a tertiary care hospital so that necessary interventions related to early diagnosis and prevention of hospital-acquired legionellosis can be initiated.

Material & Methods

The study was conducted in the department of Microbiology of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Raipur, a tertiary care hospital in central India over a period of two months from July to August 2016. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Thirty water outlets in various patient care areas of the hospital were sampled. From each outlet, water samples and swabs from the inner portions of the outlet pipe were collected amounting for a total of 60 samples. Swabs were collected before water samples from the same source.

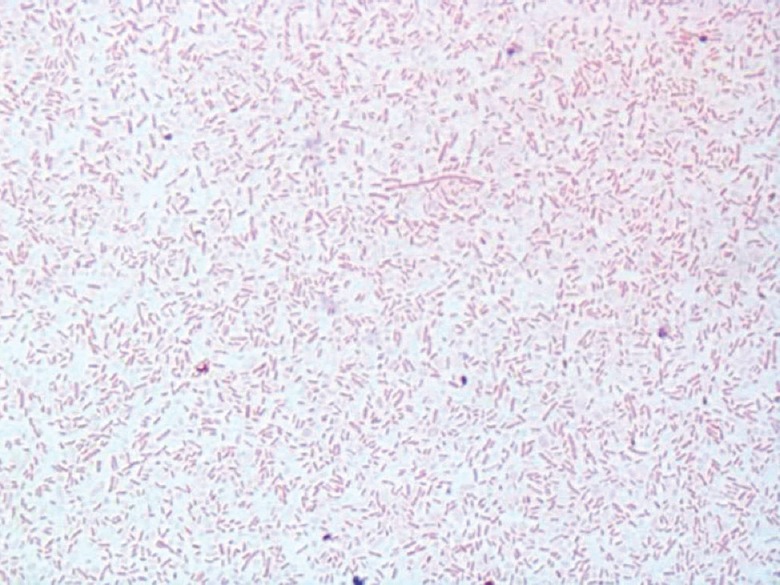

The samples were processed as per the protocol8 given by Centers for Disease Control (CDC), Atlanta. To describe briefly, filtrate of water samples and swabs were inoculated after acid buffer treatment on buffered charcoal yeast extract (BCYE) agar with and without antibiotics (polymixin B, cycloheximide, vancomycin). Cultures were examined at intervals until 14 days of incubation. Colonies of Legionella were identified as per the standard protocols8. Faintly stained Gram-negative pleomorphic bacilli (Figure)which failed to grow on blood agar or L- cysteine-free agar on subculture were suspected for Legionella species. The identification was further confirmed by latex agglutination against L. pneumophila antisera 1 and 2-15 by commercially available kit (LK04-HiLegionella Latex Kit; Himedia, Mumbai, India).

Figure.

Gram-stained morphology of the isolate identified as Legionella pneumophila the figure shows pleomorphic Gram-negative rods after Gram staining using safranine as a decolourizer for prolonged time (10 min) (×1000).

The isolates which were suspected to be Legionella but failed to agglutinate by any of the antiserum were subjected to identification by matrix-associated laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) at Post-graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh.

Statistical analysis: Results were calculated in terms of percentage positivity of the water outlets tested positive for Legionella. The proportions were compared using Fisher's exact test.

Results & Discussion

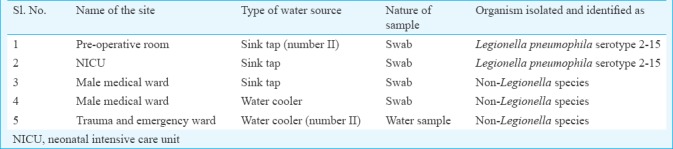

Samples including one water and four swabs, each collected from five (16.6%) different sites (Table), grew colonies suspected of Legionella species. However, only two (both from swabs) of these could be confirmed as L. pneumophila serotype 2-15 giving percentage positivity of 6.66 per cent (2/30). None of the isolates was identified as L. pneumophila serotype 1. The remaining isolates tested by MALDI-TOF were identified as Reyranella massiliensis. The swabs yielded more number of organisms as compared to water samples.

Table.

Hospital water outlets which were suspected for the presence of Legionella species

Selective BCYE alone could inhibit the growth of environmental bacteria other than Legionella in 53.33 per cent (16/30) of water samples and 30 per cent (9/30) of swabs. Acid buffer treatment was able to limit the number of organisms up to 30 per cent (9/30) on plain BCYE agar (P<0.001). It was useful to limit the growth of organisms in 70 per cent (21/30) samples on BCYE with added antibiotics (P<0.001). Acid buffer treatment resulted in further growth inhibition of the L. pneumophila isolates.

Routine environmental surveillance for L. pneumophila has been a matter of debate over the years. The CDC does not support routine environmental culture for Legionella species in the absence of recognized disease, with the exception of transplant unit, because of the supposedly ill-defined relationship between the presence of the organism in the water system and risk of acquiring the infection9. However, this approach was countered by different prospective studies across the world in which cases of hospital-acquired legionellosis were discovered subsequent to the identification of Legionella colonization of the hospital water supply10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17.

The present study reported positivity of 6.66 per cent for L. pneumophila which was less as compared to the previously reported positivity of 76 and 33 per cent from Indian hospitals4,7 as well as in the western literature 38 per cent (range 5-83%)2, 3718 and 63 per cent19. Some of the studies have reported positivity rate of <30 per cent (12-18.7%)20,21 or even zero6. The positivity cut-off of >30 per cent has been used and confirmed by many researchers to indicate the extent of colonization by L. pneumophila in any hospital warranting active clinical surveillance of legionnaire's disease3,11,21. Colonization in only 6.66 per cent of water outlets obtained in our study does not warrant active screening for the legionnaires’ disease in the hospitalized patients. On the contrary of highest reported serotype 1 of L. pneumophila, we isolated serogroup 2-15 in our study that has been equally reported worldwide2,18,19.

Sampling directly the biofilms using swabs was considered better compared to water in increasing the yield of isolation3,4. Acid buffer treatment of samples was effective in reducing the contamination; although, it was found to be detrimental to the growth of L. pneumophila. Hence, sampling of biofilms without acid buffer treatment, streaked on selective BCYE agar may be considered as the most sensitive method for recovering Legionella.

Quantification of environmental samples was tried on water samples by measuring the number of colony forming unit/ml of water cultured as doing so may provide information crucial for assessing the risk of transmission and identifying impending outbreaks. However, it did not prove much useful in our study because on most of the occasions, water culture grew confluent growth of mixed bacteria, making it very difficult to quantitate the slowly growing Legionellae. Another limitation of our study was that we did not include hospital-acquired pneumonia cases. Therefore, it was not possible to establish an association between the isolation of Legionellae with hospital-acquired pneumonia.

The extent of Legionella colonization in hospital water outlets was found to be very less precluding the necessity of incorporating specialized Legionella diagnostics in the routine workup of patients with hospital-acquired respiratory infections. However, repeated periodic environmental sampling and active case finding for hospital-acquired legionellosis in areas with positive reports need to be undertaken to confirm or reject its role as a potential nosocomial pathogen in hospital environments.

Acknowledgment

Authors acknowledge Dr Palllab Ray, Professor, Department of Microbiology and the technical staff of Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, for their help in identification of the isolates by MALDI-TOF instrument, and thank Ms. Swati Pathak, Shri Nithin Varghese and other technical staff at the department of Microbiology, AIIMS, Raipur, for the technical help extended to carry out this study.

Footnotes

Financial support & sponsorship: The authors thank the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India for considering the project for approval under ICMR short term studentship project for the year 2015-2016.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Arnow PM, Chou T, Weil D, Shapiro EN, Kretzschmar C. Nosocomial Legionnaires’ disease caused by aerosolized tap water from respiratory devices. J Infect Dis. 1982;146:460–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.4.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stout JE, Muder RR, Mietzner S, Wagener MM, Perri MB, DeRoos K, et al. Role of environmental surveillance in determining the risk of hospital-acquired legionellosis: A national surveillance study with clinical correlations. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:818–24. doi: 10.1086/518754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stout JE, Yu VL. Environmental culturing for Legionella: Can we build a better mouse trap? Am J Infect Control. 2010;38:341–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anbumani S, Gururajkumar A, Chaudhury A. Isolation of Legionella pneumophila from clinical & environmental sources in a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:761–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agrawal L, Dhunjibhoy KR, Nair KG. Isolation of Legionella pneumophila from patients of respiratory tract disease & environmental samples. Indian J Med Res. 1991;93:364–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahl S, Wali JP, Handa R, Rattan A, Aggarwal P, Kindo AJ, et al. Legionella as a lower respiratory pathogen in North India. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 1997;39:81–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudhry R, Dhawan B, Dey AB. The incidence of Legionella pneumophila: A prospective study in a tertiary care hospital in India. Trop Doct. 2000;30:197–200. doi: 10.1177/004947550003000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. Procedures for the Recovery of Legionella from the Environment. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for preventing health-care-associated pneumonia, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu VL. Resolving the controversy on environmental cultures for Legionella: A modest proposal. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1998;19:893–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabrià M, Mòdol JM, Garcia-Nuñez M, Reynaga E, Pedro-Botet ML, Sopena N, et al. Environmental cultures and hospital-acquired Legionnaires’ disease: A 5-year prospective study in 20 hospitals in Catalonia, Spain. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25:1072–6. doi: 10.1086/502346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu VL, Beam TR, Jr, Lumish RM, Vickers RM, Fleming J, McDermott C. Routine culturing for Legionella in the hospital environment may be a good idea: A three-hospital prospective study. Am J Med Sci. 1987;294:97–9. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198708000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muder RR, Yu VL, McClure J, Kominos S. Nosocomial legionnaires disease uncovered in a prospective pneumonia study: Implications for underdiagnosis. JAMA. 1983;249:3184–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joly J, Alary M. Occurrence of nosocomial legionnaires disease in hospitals with contaminated potable water supply. In: Barbaree JD, Breiman RF, Dufour AP, editors. Legionella: Current status and emerging perspectives. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudin JE, Wing EJ. Prospective study of pneumonia: Unexpected incidence of legionellosis. South Med J. 1986;79:417–9. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198604000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goetz AM, Stout JE, Jacobs SL, Fisher MA, Ponzer RE, Drenning S, et al. Nosocomial Legionnaires’ disease discovered in community hospitals following cultures of the water system: Seek and ye shall find. Am J Infect Control. 1998;26:8–11. doi: 10.1016/s0196-6553(98)70054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson JT, Yu VL, Best MG, Vickers RM, Goetz A, Wagner R, et al. Nosocomial legionellosis in surgical patients with head-and-neck cancer: Implications for epidemiological reservoir and mode of transmission. Lancet. 1985;2:298–300. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tesauro M, Bianchi A, Consonni M, Pregliasco F, Galli MG. Environmental surveillance of Legionella pneumophila in two Italian hospitals. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2010;46:274–8. doi: 10.4415/ANN_10_03_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu PY, Lin YE, Lin WR, Shih HY, Chuang YC, Ben RJ, et al. The high prevalence of Legionella pneumophila contamination in hospital potable water systems in Taiwan: Implications for hospital infection control in Asia. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:416–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu WK, Healing DE, Yeomans JT, Elliott TS. Monitoring of hospital water supplies for Legionella. J Hosp Infect. 1993;24:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(93)90084-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boccia S, Laurenti P, Borella P, Moscato U, Capalbo G, Cambieri A, et al. Prospective 3-year surveillance for nosocomial and environmental Legionella pneumophila: Implications for infection control. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;27:459–65. doi: 10.1086/503642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]