Abstract

Understanding survivors’ perspectives on treatment is important in a patient-centered approach to developing interventions for traumatic loss. Focus groups were conducted with 23 motor vehicle crash, suicide, and homicide survivors. Survivors’ attitudes towards a modular treatment for traumatic loss were assessed. This study also sought to explore survivors’ perspectives on the acceptability of existing evidence-based practice elements in the treatment of bereavement-related mental health problems. Qualitative analyses suggest that survivors liked a modular treatment approach and agreed that existing practice elements could be useful in addressing bereavement-related concerns. Implications for developing a modular treatment package for traumatic loss are discussed.

Violent forms of death and dying are tragically commonplace in the United States, with as many as 50% of adults losing a loved one to violence, accidents, or disasters at some point during their lifetime (Kilpatrick et al., 2013). Of these violent forms of death and dying, motor vehicle crashes (MVCs), suicide, and homicide are most prevalent and among the leading causes of death for young people ages 15 to 24 (Hoyert & Xu, 2012). Because of the sudden and often gruesome nature of many of these losses, family members and close friends of the deceased are at risk for a number of often co-occurring mental health problems, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and prolonged grief disorder (PGD), a condition also variously known as complicated grief (Amick-McMullen, Kilpatrick, Resnick, 1991; Kaltman & Bonanno, 2003; McDevitt-Murphy, Neimeyer, Burke, Williams, & Lawson, 2012; Zinzow, Rheingold, Hawkins, Saunders, & Kilpatrick, 2009). If left untreated, these conditions are associated with significant functional impairment (e.g., Williams, Burke, McDevitt-Murphy, & Neimeyer, 2012), thus underscoring the need to develop and evaluate effective treatments for traumatically bereaved individuals.

To date, the interventions garnering the most empirical support in terms of treatment effectiveness for bereavement-related mental health problems following violent loss are group-based interventions including Murphy and colleagues’ (1998) broad spectrum group treatment and Rynearson’s Restorative Retelling for Violent Loss treatment (Rynearson & Correa, 2008). Both treatments are structured, 10-week interventions that include a combination of psychoeducation about common grief reactions and skill building exercises intended to help participants manage distress reactions, although the groups also differ in important ways (e.g., the Restorative Retelling protocol includes several exposure-based sessions in which participants retell the story of their loved one’s dying). In a randomized controlled trail, the broad spectrum group treatment was associated with a reduction in general distress among recently bereaved mothers who lost children to violent deaths (Murphy et al., 1998), and two recent uncontrolled open trials of Restorative Retelling suggest that this intervention is associated with reductions in PTSD, depression, and PGD symptoms (Rheingold et al., 2015; Saindon et al., 2014).

The development and evaluation of individual treatments for violent loss, though, has not kept pace with the development and evaluation of group treatments. Further, these group treatments are not necessarily designed to address the needs of those with significant, impairing psychopathology but rather to teach skills related to recovery from unnatural loss. So, devoting more attention to the development and evaluation of individual treatments for violent loss survivors should be an important priority for clinicians and researchers, especially since there is a great deal of diversity in terms of post-loss clinical outcomes among this population. Consider, for example, that a single violent loss survivor could present with primary symptoms of PTSD, depression, PGD, or any combination of these symptoms. Individual treatments would arguably provide more flexibility in terms of tailoring treatments directly to the needs of individual survivors.

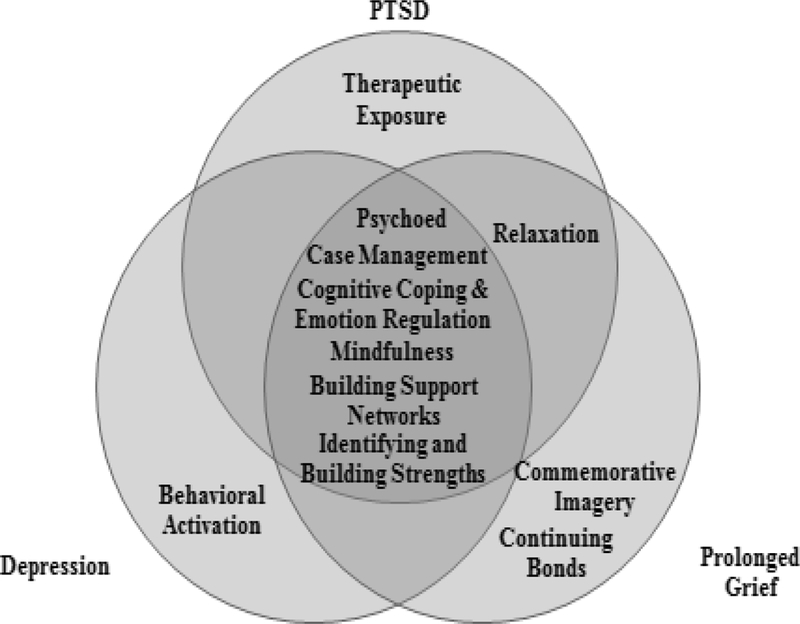

Fortunately, clinicians and researchers working in this area need not start from scratch given that many individual, evidence-based treatments exist for PTSD (e.g., Foa, Hembree, & Rothbaum, 2007), depression (e.g., Cuijpers, van Straten, & Warmerdam, 2007; Dimidjian et al, 2006), and PGD (e.g., Shear, Frank, Houck, & Reynolds, 2005). These treatment protocols include a variety of specific practice elements, or clinical techniques (Chorpita, Daleiden, & Weisz, 2005), many of which are shared across treatment protocols for different disorders. Practice elements utilized in evidence-based treatments for PTSD, depression, and PGD include relaxation strategies, cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation, and variants of therapeutic exposures (see Figure 1). Indeed, both Murphy and colleagues’ broad spectrum group treatment and Restorative Retelling integrate many of these practice elements into their protocols. Recently, Pearlman, Wortman, Feuer, Farber, and Rando (2014) developed a manualized individual treatment for violent loss that also integrates practice elements from evidence-based treatments for PTSD, depression, and PGD, although, as of this writing, this approach has yet to be evaluated in any systematic way. Beyond Pearlman et al.’s treatment approach, though, violent loss survivors are grossly underrepresented in the evidence-based treatment literature, so a question that remains unanswered is whether the practice elements being integrated into individual treatment protocols are generally viewed as acceptable to the very individuals who would be receiving these treatments. Obtaining direct feedback from violent loss survivors as it relates to intervention development and acceptability may help mitigate problems associated with dropout and retention associated with many existing evidence-based trauma treatments (Najavits, 2015).

Figure 1.

Evidence-based treatment practice elements.

Integrative treatments like the one developed by Pearlman and colleagues (2014) represent a major step forward in the development of individual treatments for violent loss survivors. Given the variety of clinical presentations associated with violent loss, however, these treatments should be designed and applied in a modular way – that is, consisting of specific practice elements, or modules, that can function independently and be used with a specific patient depending on that patient’s presenting problems and current needs (see Chorpita et al., 2005). In their approach, Pearlman and colleagues argue that treatment for violent loss should address both the trauma and grief associated with the loss. Given that violent loss is associated with multiple outcomes that may or may not involve chronic traumatic stress and/or grief reactions (e.g., bereaved patients may present with a primary diagnosis of major depression with no comorbid PTSD or PGD), a modular approach to treatment makes sense as a strategy for ensuring that clinicians can tailor treatment to patients based on their unique problems and needs.

The purpose of this study was to obtain violent loss survivors’ perceptions on a modular approach to traumatic grief treatment as well as feedback about specific practice elements that would be included in this treatment. Specific practice elements discussed in the context of a proposed modular treatment were selected by the first two authors based on a review of the existing PTSD, depression, and PGD literature. We also hoped to assess survivors’ responses with regard to treatment needs not addressed by these practice elements, as well as barriers to and facilitators of recovery that may be relevant for providers and clinicians seeking to implement treatment.

Method

Participants

Twenty-three violent loss survivors attended focus groups held at a Southeastern medical university. The final sample included two men (8.7%) and 21 women (91.3%), with an average age of 49.82 years (SD = 12.54). The majority of participants were Caucasian (n = 15, 65.2%), with the remaining participants identifying as African American (n = 8, 34.8%). In terms of relationship status, nearly half of the sample reported being married (n = 11, 47.8%). The remaining participants reported that they were single or in a relationship but not married (n = 4, 17.4%), separated or divorced (n = 6, 26.1%), or widowed (n = 2, 8.7%). Participants endorsed a wide range of yearly income levels such that five participants reported making $75,000 or more per year (21.7%), 12 reported making between $25,000 and $75,000 per year (52.2%), and six reported making less than $25,000 per year (26.1%). Six participants (26.1%) were MVC fatality survivors, nine (39.1%) were suicide survivors, and eight (34.8%) were homicide survivors. Time since death ranged from 20 months to 35 years (M = 9.57 years, SD = 8.51). Seventeen participants (73.9%) reported seeking and receiving some form of mental health treatment related to their loss.

In terms of kinship to the deceased, 10 (43.4%) participants were parents of the deceased, four (17.4%) were siblings, three (13.0%) were children of the deceased, and three were spouses or partners of the deceased (13.0%). The remaining three (13%) participants included a surviving granddaughter, step-parent, and cousin. The deceased individuals represented by surviving family members included 13 males (56.5%) and 10 (43.5%) females who were, on average, 31 years old at the time of death (SD = 16.90).

Measures

At the beginning of each focus group, participants completed a series of questionnaires assessing bereavement-related mental health problems as well as a demographics form assessing information including age, race, gender, relationship and income status, and information about their deceased loved one.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

PTSD was assessed using the PTSD Checklist (PCL; Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993). The PCL is a 17-item self-report measure where each item directly corresponds to the PTSD symptoms outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Participants indicate how much they were bothered by each symptom in the past month using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“extremely”). Items are summed to yield an overall PTSD severity score with higher scores suggestive of more severe symptoms. A cut-score of 50 is widely used to indicate a positive screen for PTSD (Ruggiero, Del Ben, Scotti, & Rabalais, 2003; Yeager, Magruder, Knapp, Nicholas, & Freuh, 2007). The PCL demonstrated excellent reliability in other samples of bereaved individuals, including violent loss survivors (Bonanno et al., 2007; McDevitt-Murphy et al., 2012) and further demonstrated good reliability in this sample (α = .89).

Depression.

Depression was assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory – II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). The BDI-II is a 21-item self-report measure of depressive symptoms rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. Items are summed to create an overall score where higher scores are suggestive of more severe depressive symptoms. A score of 14 or higher is considered suggestive of at least mild depression (Beck et al., 1996). The BDI-II has well established psychometric properties and has been used in other samples of violent loss survivors (McDevitt-Murphy et al., 2012). The BDI-II also demonstrated excellent reliability in the current sample (α = .91).

Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD).

PGD was assessed using the revised Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG; Prigerson & Jacobs, 2001), a 30-item self-report measure assessing PGD symptoms. Questions are rated on a 5-point Likert scale with higher scores indicating more frequent/intense symptoms. Questions on this measure include 19 items from the original ICG, and we computed a summed score based on these original 19 items. A widely applied cut-score of 25 was used to identify individuals screening positive for PGD (Prigerson et al., 1995). The ICG has shown excellent psychometric properties in other samples of bereaved adults (e.g., Keesee, Currier, & Neimeyer, 2008; Schnider, Elhai, & Gray, 2007) and, in this study, the 19 items from the original ICG demonstrated excellent internal consistency with a Chronbach’s alpha of .88.

Procedure

Adult survivors of MVC, suicide, or homicide loss who were at least 18 years old and more than one year post-loss were eligible to participate. Participants were recruited via several different methods, including online advertisements and flyers posted throughout the medical center. Interested participants who responded to one of the recruitment methods were informed about the study via telephone and assigned to a focus group according to type of loss (i.e., MVC, suicide, homicide). In all, four, 90-min focus groups were conducted - two groups with MVC survivors (n = 6; 3 participants per group), one group of suicide survivors (n = 9), and one group of homicide survivors (n = 8). All groups were facilitated by the first author who used a series of key questions (see Table 1) to guide group discussions, and each focus group was audio recorded. A co-facilitator was also present to take notes.

Table 1.

Focus group key questions.

| 1. What are some things that have been most helpful to you since your loss? |

| 2. Are there things that have been harmful to you since your loss? |

| 3. Do you think this approach will be helpful in addressing some of the challenges individuals face following violent loss? Why? |

| 4. What do you like best about this treatment? |

| 5. What do you like least about this treatment? |

| 6. What modules do you think are most necessary? |

| 7. What modules are you most concerned about? |

| 8. Do you think there are things that might make it difficult for survivors to engage in a treatment program like this? If so, what kinds of things? |

| 9. What advice do you have for improving this approach? |

| 10. Many of the techniques used in the current approach were developed with the needs of different trauma survivors or bereaved individuals in mind. Are there any special issues we should consider when applying this treatment to violent loss survivors? |

| 11. Are there other modules that you think we should consider including in this treatment approach? |

Note: For these focus groups, we used the term “modules” in lieu of “practice elements,” although, for the purposes of this manuscript, we use the two terms interchangeably.

Prior to beginning the focus groups, participants completed self-report measures of bereavement-related mental health problems. After completing measures, group discussions were facilitated by the study PI, who has extensive experience working with traumatic grief. Focus groups began with a discussion about facilitators of and barriers to post-loss recovery, and participants were then presented with information about a proposed modular, traumatic grief treatment that combines practice elements from existing evidence-based treatments for PTSD, depression, and PGD. This information included descriptions about each of the practice elements (see Figure 1). The remainder of the group involved a discussion about participants’ reactions to the treatment and practice elements. Participants were each compensated for their time with a $20 gift card. All study procedures were approved by the university IRB, and all participants provided informed consent prior to data collection.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine the level of symptoms on the PTSD, depression, and PGD measures, and participants across groups were compared on these symptom measures using a series of one-way ANOVAs. For qualitative analyses, all focus group recordings were transcribed and coded for key themes and responses for each group. Two independent raters each prepared lists of observed themes from each group, and lists were examined for patterns that were used to summarize themes. Reliability of the findings was addressed by examining consistency of themes across groups and agreement among independent raters (Manfredi, Lacey, Warneck, & Balch, 1997). Final decisions regarding any discrepancies between coders were made by the PI.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Across groups, there was considerable variability in terms of symptom severity on self-report measures of bereavement-related mental health outcomes. The mean score on the PCL was 42.39 (SD = 12.99), with 30.4% of participants (n = 7) screening positive for PTSD. The mean score on the BDI was 14.65 (SD = 9.19), and approximately 52.2% of participants (n = 12) screened positive for at least mild depression. On the ICG, the mean score was 26.87 (SD = 13.17), and 52.2% of participants (n = 12) screened positive for PGD. Symptom severity scores did not statistically differ for MVC, suicide, and homicide survivors (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Bereavement-related mental health outcomes by type of loss.

| MVC M (SD) |

Suicide M (SD) |

Homicide M (SD) |

Test Statistic (df) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCL | 39.67 (12.72) | 40.44 (13.27) | 46.63 (13.49) | F(2,20)=.64 |

| BDI-II | 10.83 (4.54) | 15.56 (11.64) | 16.50 (8.85) | F(2,20)=.70 |

| ICG | 19.50 (13.20) | 24.67 (14.76) | 34.88 (6.79) | F(2,20)=3.00 |

Note. PCL = PTSD Checklist; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; ICG = Inventory of Complicated Grief; MVC = Motor vehicle crash.

Focus Group Themes

In this section, themes that emerged from the focus groups are presented in a way that corresponds to the key questions.

Facilitators of and barriers to post-loss recovery.

Across focus groups, many participants discussed the role of social support in facilitating adaptation to bereavement. While this included emotional support from family and friends, some participants recalled that grief-specific support from other bereaved individuals, including co-workers, parishioners at church, and members of local grief support groups, helped promote a sense of recovery. Participants noted that such grief-specific support from acquaintances was often helpful in that these interactions helped normalize and validate their own grief responses as well as promote a sense of “commonality” and connectedness with other survivors. Several participants also discussed the role of faith and spirituality in facilitating adaptation to bereavement, especially in terms of helping survivors create a sense of meaning following their loved one’s death. When asked what she found most helpful after the death of her grandmother in a MVC, for example, one survivor said simply, “Family, friends, and, by far, faith in God and knowing that he was in control.”

However, just as social support was seen as helpful by many individuals, negative social support and perceived social isolation were consistently identified as barriers to adapting to the bereavement process. Many participants described feeling hurt and frustrated in response to “insensitive” comments from family and/or friends, especially when those comments invalidated the bereaved person’s ongoing expressions of grief. For example, describing her own experience with bereavement, one homicidally bereaved mother explained, “Some people, some people’s family, think you are supposed to be done and gotten over it by now. So sometimes they put you under more pressure.” Similarly, one suicide survivor recalled:

“You can have wonderful family and friends, but people’s lives move on, and yours doesn’t necessarily move on. So you have a lot of support, weeks, months after, and then, you know, people think you are doing okay. And you think you are doing okay and things start to progress like your life was when that person [the deceased loved one] was still here. And then you fall back and realize that you’re not okay, and you feel bad because people don’t necessarily want to listen to you talk about it anymore.”

Within groups, MVC survivors described travel anxiety as an important barrier to post-death adaptation as being in a car was a constant reminder of the loss and potential for future harm. A few suicide survivors felt that participation in a non-directive suicide support group was potentially harmful early after their loss, especially when group discussion centered around the circumstances of the death event. Recalling her own support group experience shortly after her daughter’s suicide, one bereaved mother said, “I went in and basically everybody just tells their story. You know, I went for a few months, and I just finally got to a point where I had to stop going. All I felt like was, ‘Okay I’m telling the story but it’s not moving me forward at all.’” Homicide survivors spoke about post-death barriers associated with the legal system, often feeling frustrated with the perceived lack of communication between law enforcement officials and family members.

Likes and dislikes about proposed practice elements for a modular-based traumatic grief treatment.

In regard to the proposed treatment approach, participants across groups overwhelmingly agreed that they liked a modular approach that combined practice elements from treatments for PTSD, depression, and PGD. Generally speaking, participants also liked most of the practice elements included in the treatment model and felt that all elements were at least potentially important in facilitating recovery from a violent death. Participants noted, however, that they especially liked practice elements that provided survivors with practical assistance in the form of grief-specific information especially related to traumatic loss and/or tangible resources. In particular, participants liked the psychoeducation practice element, recommending that this element be a universal component of traumatic grief treatment. Discussing the importance of psychoeducation, participants felt that education about common responses to traumatic loss as well as grief-related mental health problems (e.g., PTSD, depression, PGD) would help normalize symptoms as well as help grieving individuals anticipate potential triggers for trauma and grief-related symptoms, including symptoms associated with holidays, birthdays, and/or death anniversaries. Furthermore, psychoeducation was seen as a way of helping survivors build trusting relationships with therapists in that it helps convey the therapist’s recognition that traumatic grief is different from non-traumatic grief. Many participants also noted that they especially liked case management as a component for traumatic grief treatment but acknowledged that this practice element may only be relevant to individuals with more pressing, practical needs (e.g., transportation, food, housing). Furthermore, several participants also liked the building strengths and building support networks practice elements in that these were seen as ways of helping participants move through the grief process by improving social support and connectedness.

Even though participants generally did not dislike any of the practice elements, per se, they did explain that some of the practice elements targeting trauma symptoms in particular could be painful for survivors and require sensitivity on the part of the clinician in terms of assessing survivors’ readiness and willingness to engage in them. This was especially true of the retelling the narrative of the death element. However, participants across groups generally felt that this element was a vital part of traumatic grief treatment, with one mother who lost her son in a MVC describing retelling the narrative of the death as follows:

“I think it’s like if you’re a surgeon or something, the first time you go into an operating room you might pass out, but then you have to keep coming back and back and back and you sort of desensitize yourself to it. And I think retelling the story is similar to that.”

Strengths and weaknesses of a modular-based approach to traumatic grief treatment.

Participants noted that a major strength of a modular approach to traumatic grief treatment is that such an approach allows treatment to be tailored to each survivor depending on his or her unique symptoms and circumstances. Describing the approach, one suicide survivor said, “It’s a very multi-disciplinary approach, and I think that you’ve got such a wide variety of modalities that you’re going to be trying - something or two, three, four things are going to resonate with people.” Or, as one homicide survivor described, “Everybody’s wishes are different.” Participants also said that another strength of the treatment is that we conceptualized this approach as an individual treatment. They noted that although connecting and gaining support from others in a group format can be useful, not all survivors may feel comfortable in a group setting and not all communities may have the capacity to run groups. A major weakness that participants noted in the modular-based traumatic grief treatment is that the treatment could seem “overwhelming” for survivors given the number of potential issues and practice elements that may be addressed in treatment.

Special issues for delivering traumatic grief treatment with violent death survivors.

Focus group participants raised several key issues for clinicians to consider when working with violent death survivors. For one, when implementing evidence-based practice elements, clinicians and patients should work collaboratively to ensure that therapeutic exercises and assignments are personally relevant to survivors. For example, participants discussed seeking continuing bonds with their loved ones in a variety of ways, including scrapbooking, writing letters to the deceased, and, in one case, even keeping some of the loved one’s ashes in a necklace around the participant’s neck. Similarly, several participants noted that mindfulness may be helpful as a relaxation strategy for survivors, but a few participants indicated that they would not want mindfulness-based practice elements in their own treatment given that it seemed to “delve into people’s religion.” Beyond mindfulness, participants noted several personally relevant relaxation strategies, including walking, swimming, and yoga. As a final example of the issue that clinicians and patients should work collaboratively to ensure that therapeutic exercises are personally relevant to survivors, several survivors noted the importance of reengaging in pleasant activities via behavioral activation, but a few participants noted that this may involve helping survivors identify new pleasant and meaningful activities rather than simply reengaging in activities that were pleasant prior to the loved one’s death.

Participants also raised the importance of timing in terms of deciding when to implement specific practice elements in treatment. One suicide survivor stated succinctly, “I think what you’re going to have to do is you’re going to have to come up with a way that when they [survivors] come to you, you’re going to have to screen as far as where they are in crisis most at that time.” Considering time since loss, participants felt that psychoeducation and case management would be especially helpful for survivors experiencing acute bereavement but generally felt that trauma-focused practice elements including retelling the narrative of the death should not be implemented in the acute bereavement phase.

Furthermore, participants mentioned that clinicians need to be aware of the complex cognitive and emotional experiences survivors will likely have in the context of traumatic grief treatment – experiences that can signal the need to either proceed with or discontinue a particular practice element. Participants noted that, throughout their grief, they experienced (and continue to experience) a range of emotions including sadness, fear, guilt, and anger, emotions that will likely influence participation in treatment. For example, while discussing the commemorative imagery practice element, one suicidally-bereaved participant recalled feeling angry at the deceased after the death and noted that she would not have wanted to commemorate the deceased at that time. “I was very angry and like, I didn’t want that reminder in front of me,” she said.

Future directions for traumatic grief treatment.

Several participants felt that individual treatment could be enhanced with conjoint family sessions given that family members will share similar experiences associated with the death. Participants also suggested additional practice elements that may benefit survivors seeking traumatic grief treatment. Specifically, some survivors suggested that, in addition to an imaginal retelling of the death narrative, survivors may benefit from in vivo exposure exercises, including revisiting the location where the death occurred. For example, one bereaved mother reflecting on her own experience in therapy after her son’s murder recalled:

“When I first came to counseling, I had to talk about the death. Because he [therapist] told me that in order to be an overcomer of anything you have to go…he sent me back in the house where my son was murdered. He said you have to go through that in order to go forward. I went back inside with my daughter because she wouldn’t let me go in there by myself, and we started talking about my son and how he used to look out the window. And we got such a peace. So I think in order for you to get healed, you’re going to have to face the death.”

A few participants noted that substance misuse may be a concern for some survivors and further suggested that optional practice elements for substance misuse be incorporated into individual treatment protocols for survivors.

Discussion

This study explored violent loss survivors’ attitudes and opinions about a modular approach to traumatic grief treatment as well as perspectives on specific practice elements that would be included in this treatment. The participants in these focus groups matched similarly to survivors who typically seek treatment (e.g., majority middle-age women; Rheingold et al., 2015). Further, symptom presentation of focus group participants was consistent with other samples of violent loss survivors (e.g., McDevitt-Murphy et al., 2012; Williams & Rheingold, 2015) with roughly a third reporting significant PTSD symptoms and a half reporting depressive symptoms suggesting that views expressed in these focus groups were potentially representative of typical survivors.

Results of these focus groups suggest that violent loss survivors overwhelmingly liked the idea of a modular approach to treatment that can be tailored to each survivor depending on his or her unique symptoms and needs. Order of modules should be patient-centered in that clinicians should take into account survivor input when determining course. In doing so, survivors may feel a sense of control and validation in their grief recovery. Timing of modules should also be considered in relation to time since loss and other environmental issues that may impact distress and recovery. For example, survivors that enter treatment shortly after their loss (i.e., less than 3 months) may benefit from psychoeducation, social support, and strength building initially as an early intervention before approaching other modules. Moreover, anniversaries and legal court proceedings need to be incorporated into the planning of module decision-making.

Focus group participants generally had a positive response to each of the proposed practice elements drawn from evidence-based treatments for PTSD, depression, and PGD and believed that each practice element could be helpful for violent loss survivors. Importantly, many of these survivors screened positive for at least one bereavement-related mental health condition (i.e., PTSD, depression, PGD), suggesting that this treatment approach was generally viewed as acceptable and helpful by not just well-adjusted survivors but also by survivors with significant bereavement-related mental health problems. This is a relevant and valuable point to stress given that clinicians in the field sometimes are concerned with providing exposure-based practices to traumatically bereaved individuals for apprehension that the intervention would not be tolerated by distressed survivors. As focus group participants noted, addressing death images or reminders of the nature of the loss, although difficult, may be a necessary component to recovery and should not be avoided. Clinicians, however, need to be sensitive to the timing and approach to such strategies.

Focus group participants’ responses were consistent with the literature on the important role that social support can play in the recovery of trauma and loss as well as negative support can play in aggravating responses. For instance, in a sample of homicidally-bereaved African American adults, available social support was inversely related to prolonged grief symptoms, while negative support was associated with increased grief and PTSD symptoms (Burke, Niemeyer, & McDevitt-Murphy, 2012). Several survivors in this study also discussed feeling hurt when family and/or friends made comments that served to invalidate their ongoing expressions of grief. Thus, a module aiming to help survivors build meaningful support networks may also need to address communication skills such as how to communicate with others about the loss and effectively ask for desired support from available support persons.

While there was generally consensus across groups with regard to likes and dislikes about the modular-based treatment and its proposed components, we noted important group differences in terms of perceived facilitators of and barriers to recovery. Homicide survivors, for example, generally identified stress associated with the legal system as a barrier to recovery – a finding replicated in other studies involving homicide survivors (e.g., Englebrecht, Mason, & Adams, 2014). MVC survivors, on the other hand, uniformly identified travel anxiety as a barrier to post-loss recovery. Highlighting these differences by type of loss can be important for clinicians working with violent loss survivors in the context of individual treatment in that these barriers to recovery can undermine session engagement and attendance. Therefore, traumatic loss interventions should include information about common stressors and barriers faced by individuals experiencing different types of loss so that clinicians can address these issues in treatment as is appropriate.

Participants in this study also offered suggestions for additional practice elements that they felt would be helpful for some violent loss survivors in the context of a modular treatment package. One such practice element that was mentioned by survivors across groups was in vivo exposure. That is, many participants, through their own experiences, felt that revisiting the death scene was helpful in terms of symptom reduction. In vivo exposure is an important component of many evidence-based treatments for PTSD (e.g., Foa et al., 2007) and, in line with the feedback offered by these participants, has increasingly received attention from clinicians and researchers as a promising intervention for psychological symptoms associated with sudden, violent loss (e.g., Kristensen, Tønnessen, Weisaeth, & Heir, 2012). A few participants also insightfully noted that many survivors have difficulties with substance misuse during the course of bereavement, and including modules with practice elements relevant to the management of substance misuse may help enhance treatment effects for survivors with comorbid affective and substance use problems. Self-medication models of trauma and substance use frame substance use as a means of avoiding or managing trauma-related negative affect and distress (Khantzian, 1997). Research suggests that traumatic loss increases risk for substance use difficulties (e.g., Pfefferbaum & Doughty, 2001) and, thus, should not be neglected during screening or treatment and potentially integrated into intervention.

Although this study provides some initial validation that many of the evidence-based practice elements used in treating violent loss survivors are generally viewed as acceptable to survivors, there are also several limitations worth mentioning. First, our sample may have been biased in that these were individuals who responded to our recruitment materials, and, thus, their attitudes and opinions regarding a modular traumatic grief treatment and its component parts may not be representative of violent loss survivors more generally. Relatedly, a majority of these participants had participated in some form of mental health treatment related to their loss and may have been more receptive to proposed practice elements they had already encountered in treatment in the past. Second, we should acknowledge that even though participants generally liked the proposed module-based treatment approach and its component parts, this does not necessarily mean that such an approach is effective from a treatment standpoint. This approach should ultimately be evaluated in terms of its feasibility, clinical utility, and treatment effectiveness. Nevertheless, this study is an important first step in developing a modular treatment for violent loss survivors in that ensuring the acceptability of the proposed treatment methods to survivors may facilitate adoption and minimize drop-out. Furthermore, this study contributes to the violent loss treatment literature more generally by examining survivors’ perspectives regarding needs of bereaved individuals that should be addressed in treatment. We are hopeful that these findings will support these next steps in the development and evaluation of an effective, evidence-based treatment that will, to use one survivor’s words, help those who are grieving move from “surviving” to “thriving.”

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research Institute voucher award (NIH/NCRR#UL1RR029882, voucher #5598–0001 PI: Williams). Manuscript preparation was supported by NIMH Training Grant T32 MH18869–26 and NIH Loan Repayment Award L30 MH104802. Portions of this work were presented at the 30th annual meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies in Miami, FL and the Restorative Retelling Conference in Seattle, WA. Address correspondence to Joah L. Williams, Department of Psychology, University of Missouri – Kansas City, 5030 Cherry Street, Kansas City, MO, 64110 or via williamsjoah@umkc.edu

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Amick-McMullan A, Kilpatrick DG, & Resnick HS (1991). Homicide as a risk factor for PTSD among surviving family members. Behavior Modification, 15, 545–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory–II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Burke LA, Neimeyer RA, & McDevitt-Murphy ME (2010). African American homicide bereavement: Aspects of social support that predict complicated grief, PTSD, and depression. Omega, 61, 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Neria Y, Mancini A, Coifman K, Litz B, & Insel B (2007). Is there more to complicated grief than depression and posttraumatic stress disorder? A test of incremental validity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116, 342–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, & Weisz JR (2005). Modularity in the design and application of therapeutic interventions. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 11, 141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, van Straten A, & Warmerdam L (2007). Behavioral activation treatments of depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 318–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, Schmaling KB, Kohlenberg RJ, Addis ME,…Jacobson NS (2006). Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 658–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englebrecht C, Mason DT, & Adams MJ (2014). The experiences of homicide victims’ families with the criminal justice system: An exploratory study. Violence and Victims, 29, 407–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, Rothbaum BO (2007). Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Emotional processing of traumatic experiences. New York, NY: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyert DL, & Xu JQ (2012). Deaths: Preliminary data for 2011. National Vital Statistics Reports, 61, 1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltman S, & Bonanno GA (2003). Trauma and bereavement: Examining the impact of sudden and violent death. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 17, 131–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keesee NJ, Currier JM, & Neimeyer RA (2008). Predictors of grief following the death of one’s child: The contribution of finding meaning. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64, 1145–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ (1997). The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 4, 231–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, & Friedman MJ (2013). National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26, 537–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen P, Tønnessen A, Weisaeth L, & Heir T (2012). Visiting the site of the death: Experiences of the bereaved after the 2004 Southeast Asian Tsunami. Death Studies, 36, 462–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi C, Lacey L, Warneck R, & Balch G (1997). Method effects in survey and focus group findings: Understanding smoking cessation in low SES African American women. Health, Education, & Behavior, 24, 786–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt-Murphy ME, Neimeyer RA, Burke LA, Williams JL, & Lawson K (2012). The toll of traumatic loss in African Americans bereaved by homicide. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4, 303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SA, Johnson C, Cain KC, Das Gupta A, Dimond M, Lohan J, & Baugher R (1998). Broad-spectrum group treatment for parents bereaved by the violent deaths of their 12- to 28-year-old children: A randomized controlled trial. Death Studies, 22, 209–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM (2015). The problem of dropout from “gold standard” PTSD therapies. F1000Prime Reports, 7, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman LA, Wortman CB, Feuer CA, Farber CH, & Rando TA (2014). Treating traumatic bereavement: A practitioner’s guide. New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum B, & Doughty DE (2001). Increased alcohol use in a treatment sample of Oklahoma City bombing victims. Psychiatry, 64, 296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, & Jacobs SC (2001). Traumatic grief as a distinct disorder: A rationale, consensus criteria, and a preliminary empirical test In Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Stroebe W, & Schut H (Eds.), Handbook of bereavement research: Consequences, coping, and care (pp. 613–645). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF, Bierhals AJ, Newsom JT, Fasiczka A, . . . Miller M (1995). Inventory of Complicated Grief: A scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Research, 59, 65–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheingold AA, Baddeley J, Williams JL, Brown C, Wallace WM, Correa F, & Rynerson EK (2015). Resorative Retelling for violent death: An investigation of treatment effectiveness, influencing factors, and durability. Journal of Loss and Trauma. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero KJ, Del Ben K, Scotti JR, & Rabalais AE (2003). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist—Civilian Version. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16, 495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rynearson EK & Correa F (2008). Accommodation to violent dying: A guide to restorative retelling and support. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Saindon C, Rheingold AA, Baddeley J, Wallace MM, Brown C, & Rynearson EK (2014). Restorative retelling for violent loss: An open clinical trial. Death Studies, 38, 251–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnider KR, Elhai JD, & Gray MJ (2007). Coping style use predicts posttraumatic stress and complicated grief symptom severity among college students reporting a traumatic loss. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 344–350. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F, Litz B, Herman D, Huska J, & Keane T (1993, October). The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JL, Burke LA, McDevitt-Murphy ME, & Neimeyer RA (2012). Responses to loss and health functioning among homicidally bereaved African Americans. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 17, 358–375. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JL, & Rheingold AA (2015). Barriers to care and service satisfaction following homicide loss: Associations with mental health outcomes. Death Studies, 39, 12–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager DE, Magruder KM, Knapp RG, Nicholas JS, & Frueh C (2007). Performance characteristics of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist and SPAN in Veterans Affairs primary care settings. General Hospital Psychiatry, 29, 294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow HM, Rheingold AA, Hawkins AO, Saunders BE, & Kilpatrick DG (2009). Losing a loved one to homicide: Prevalence and mental health correlates in a national sample of young adults. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22, 20–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]