Abstract

Anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL plays central roles in regulating programed cell death. Partial unfolding of Bcl-xL has been observed at the interface upon specific binding to the pro-apoptotic BH3-only protein PUMA, which in turn disrupts the interaction of Bcl-xL with tumor suppressor p53 and promotes apoptosis. Previous analysis of existing Bcl-xL structures and atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have suggested that substantial intrinsic structure heterogeneity exists at the BH3-only protein binding interface of Bcl-xL to facilitate its conformational transitions upon binding. In this study, enhanced sampling is applied to further characterize the interfacial conformations of unbound Bcl-xL in explicit solvent. Extensive replica exchange with solute tempering (REST) simulations, with a total accumulated time of 16 μs, were able to cover much wider conformational spaces for the interfacial region of Bcl-xL. The resulting structural ensembles are much better converged, with local and long-range structural features that are highly consistent with existing NMR data. These simulations further demonstrate that the BH3-only protein binding interface of Bcl-xL is intrinsically disordered and samples many rapidly interconverting conformations. Intriguingly, all previously observed conformers are well represented in the unbound structure ensemble. Such intrinsic structural heterogeneity and flexibility may be critical for Bcl-xL to undergo partial unfolding induced by PUMA binding, and likely provide a robust basis that allows Bcl-xL to respond sensitively to binding of various ligands in cellular signaling and regulation.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) in their unbound state do not form well-defined three-dimensional structures under physiological conditions1–3, in contrast to the conventional protein structure-function paradigm4. They are highly prevalent in biology5–7 and play critical roles in cellular signaling and regulation8–12. Mutations of IDPs13–15 and/or changes in their protein levels10, 16–17 have been implicated in numerous human diseases. There is thus an increasing interest in understanding the physical properties of IDPs and how these properties contribute to versatile functions. In particular, inherent structural fluctuations of IDPs in their unbound states are likely key to understanding how IDPs could respond rapidly and sensitively to various stimuli in cellular processes18–19.

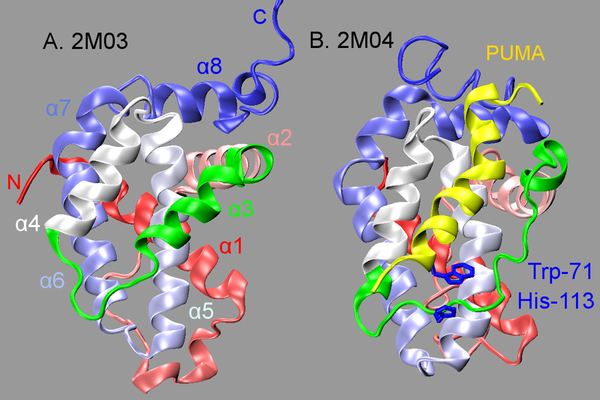

Coupled binding and folding of proteins is frequently observed in IDP interactions, during which disordered IDPs fold into stable three-dimensional structures upon specific binding20–22. It has been recently recognized that regulated unfolding of proteins is also often involved in cell signaling23. A particularly interesting example involves Bcl-xL, a pro-survival Bcl-2 family protein that regulates programed cell death24. Bcl-xL could become partially unfolded at the BH3-only protein binding interface upon specific binding to PUMA, a pro-apoptotic BH3-only Bcl-2 family protein. Note that PUMA contains intrinsically disordered regions and its BH3 domain folds into a helix upon specific binding to Bcl-xL (see Figure 1). Partial unfolding of Bcl-xL disrupts its interaction with tumor suppressor p53, which in turn abolishes p53 inhibition of Bcl-xL pro-survival functions and activates the apoptotic cascade25–27. To date, the molecular mechanisms of PUMA-induced partial unfolding of Bcl-xL have not been fully understood. Trp-71 in PUMA has been suggested to play critical roles in driving Bcl-xL local unfolding, which interacts with Bcl-xL His-113 through π-stacking interactions (Figure 1)27. However, the π-stacking interaction itself appears to contribute little to the binding of Bcl-xL with PUMA, since PUMAW71A mutant associates with wild type Bcl-xL with similar affinities27. In addition, the BH3 domain of another BH3-only Bcl-2 family protein, BAD28, also contains a Trp that could form similar Trp-His contact with Bcl-xL, but its binding does not induce Bcl-xL unfolding27.

Figure 1.

PDB structures of unbound (A) and PUMA-bound (B) Bcl-xL. Bcl-xL is shown in cartoon representation with its color changing from red (at N-terminus) to blue (at C-terminus). The BH3-only protein binding interface (residues 98–120) is highlighted in green, and the bound PUMA is shown in yellow

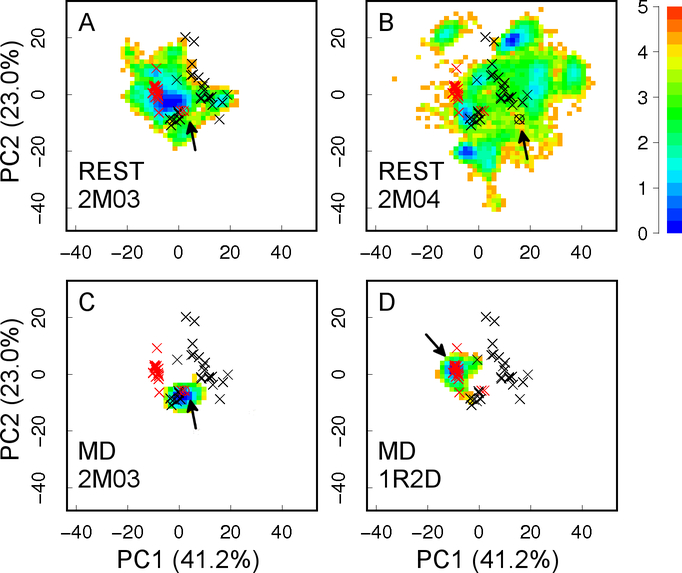

Our previous analysis of existing experimental structures of Bcl-xL in both unbound and bound states and atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have suggested that substantial intrinsic structural heterogeneity exists at the BH3-only protein binding interface of Bcl-xL29, which could provide a robust molecular basis to support Bcl-xL conformational transitions in response to ligand binding. However, atomistic simulations of the heterogeneous structural ensemble of the disordered interface of Bcl-xL is extremely challenging. Conventional MD simulations of ~300–700 ns at the room temperature did not yield converged conformational ensembles29. As illustrated in Figure 2 C and D, these simulations mainly sample local conformational space near their corresponding initial structures, and conformational spaces visited by different MD simulations do not overlap with each other. In this work, we utilize an advanced sampling technique known as replica exchange with solute tempering (REST)30–31 to calculate better converged structural ensembles of Bcl-xL in the unbound state. REST is a Hamiltonian replica exchange method, where the solute and solute-solvent energies are scaled by λ and , respectively. For the condition λ=1, the system temperature is the one of interest (T); whereas if λ<1, the effective temperature of the solute is increased to T/λ, while the solvent temperature remains at T. As designed, the exchange acceptance ratio is determined by solute energy and solute-solvent energies alone, but not the solvent energy (which is the major component of the total energy). Therefore, much fewer replicas could be used to achieve sufficient energy overlap between neighboring replicas compared with the regular temperature replica exchange32–33. Furthermore, REST allows us to focus tempering on any molecular region of interest, such as the binding interface of Bcl-xL. These properties together make REST particularly suitable for enhanced sampling of larger systems in explicit solvent with significantly reduced computational cost30–31, 34–37. In the present study, the improved sampling capability of REST has allowed the generation of much better converged structure ensembles of the BH3-only protein binding interface of Bcl-xL. The calculated ensembles have been validated by direct comparison with published NMR data, shedding light on how Bcl-xL could respond sensitively and rapidly to various binding ligands, particularly partial unfolding upon PUMA binding.

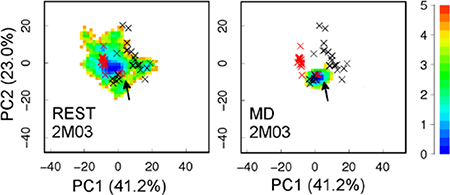

Figure 2.

Projection of simulation trajectories on the first two principal components (PCs) derived from 49 PDB structures of Bcl-xL. The positions of all PDB structures are marked with ×, with unbound and bound ones in red and black, respectively. The initial structure of each simulation is marked with an arrow. Results from MD simulations are adapted from our previous work29. The heat map shows the free energy (in kcal/mol) derived from simulation statistics. Values in the parentheses are percentages of variance associated with each PC.

METHODS

System setup and simulation protocols

Two REST simulations of unbound Bcl-xL have been performed. The initial structures were obtained from RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) entries 2M03 (unbound) and 2M04 (PUMA-bound)27. The first models from these ensembles were processed by renumbering residues in 2M03 to match that in 2M04. The bound PUMA peptide in 2M04 was removed, and only the common region of Bcl-xL (residues 1–44 and 85–200) were retained. The termini were capped with an acetyl group and N-methyl amide at the N- and C-termini, respectively. Note that the interface region (highlighted in green in Figure 1A) exhibits high-helical structure in 2M03, whereas it is almost fully disordered in 2M04 (Figure 1B). The significantly different starting structures allow one to better evaluate the level of convergence and other properties obtained from these two independent simulations. The protein was solvated using TIP3P water molecules in a rectangular simulation box constructed with at least 1.0 nm of solvent between protein and the nearest side of the box. 12 Na+ ions were added to neutralize the system. Details of the system setup are summarized in Table 1 and Figure S1.

Table 1.

Summary of system setup

| Initial Structure | Water Number | Na+ Number | Total Atom Number | Simulation Box (nm × nm × nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2M03 | 7361 | 12 | 24601 | 6.59 × 6.54 × 5.69 |

| 2M04 | 8566 | 12 | 28216 | 7.25 × 6.63 × 5.86 |

Both simulations (referred to using the initial structures, 2M03 and 2M04, hereafter) were performed using GROMACS-4.6.738 patched with PLUMED-2.1.336, 39. To begin with, energy minimization was carried out for both systems using a steepest descent algorithm. Then 50 ps NVT simulation followed by 50 ps NPT simulation was used to equilibrate the system. The equilibrated boxes were then used to initiate two independent REST simulations under NVT conditions. Only the BH3-only protein binding interface, residues 98–120, was subjected to tempering. The effective temperatures range from 298 K to 500 K, exponentially spaced among 16 replicas. The choice of 500 K as the highest temperature provides accelerated conformational diffusion without requiring a larger number of replicas to cover the temperature span. The corresponding values of the scaling factor λ are 1, 0.966, 0.933, 0.902, 0.871, 0.842, 0.813, 0.785, 0.759, 0.733, 0.708, 0.684, 0.661, 0.639, 0.617, and 0.596, respectively. The frequency of neighbor exchange attempts was every 2 ps, which is commonly used and believed to allow efficient mixing of replicas while ensuring proper equilibration prior to exchange attempts. The length of each REST simulation is 500 ns per replica, and the average exchange acceptance ratio is ~ 50%. In both simulations, weak position restraints with a force constant of 100 kJ/mol/nm2 were imposed on Cα atoms of the Bcl-xL core region, which includes residues 85–95, 123–127, 140–156, and 162–175. The core region has been shown to display minimal variance among all PDB structures of Bcl-xL29. The Amber99sb force field40 was used. Although it’s different from CHARMM36 force field used in our previous MD simulations, both force fields are well parameterized and not expected to significantly affect simulation results. The cutoff distance of van der Waals interactions was set to 1.0 nm, and the nonbonded list was updated every 5 steps. Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method41 was used to calculate long-range electrostatic interactions, with a 0.12 nm Fourier spacing. All bonds were constrained using LINCS42, and the integration time step was 2 fs.

NOE, clustering and principal component analyses

Only snapshots sampled at λ = 1 during the last 200 ns of the simulation were included in NOE analysis. For each frame, NOE-like distances were first calculated based on the r−6 summation scheme for cases involving multiple equivalent protons43–44. The averaged NOE distances for simulated ensembles were then calculated based on <r−6>−1/6 averaging scheme. Experimental NMR restraints of unbound Bcl-xL were obtained from PDB 2M03. Among the 527 total NOE distance restraints, there are 29 NOEs within the interface region (residues 98–120) and 30 NOEs between the interface and the rest of the protein. Only these 59 interface-related NOEs were considered in the assessment of the simulated ensembles. As we compute contact map between residues in the interface region and the rest of the protein, experimental NOE distance restraints from another unbound Bcl-xL structure, PDB 2LPC45, were also considered for reference.

For principal component analysis (PCA), Bcl-xL structures, either from PDB or simulation trajectories, were first aligned using Cα atoms of the core region (residues 85–98, 123–127, 140–156, and 162–175), and Cα atoms of the interface region (residues 98–120) were then analyzed. The first two principal components (PCs) were derived from 49 PDB structures that include Bcl-xL configurations in both bound and unbound states (see reference29 for more details). Snapshots from various simulation trajectories were then projected onto these two PCs. In REST simulations, we extracted conformations every 20 ps from the first condition (λ=1). The free energy surfaces were derived directly from the 2D probability distributions along the first two PCs.

Clustering analysis was performed using the “gmx cluster” tool in GROMACS. All snapshots from two REST simulations were first aligned using backbone heavy atoms of the core region (residues 85–98, 123–127, 140–156, and 162–175), and root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of backbone heavy atoms at the interface region (residues 98–120) was then used for clustering, with a cutoff value of 3.0 Å.

Conformational entropy

To quantify peptide backbone flexibility and compare sampling efficiency between MD and REST simulations, we calculated the conformational entropy for each residue’s backbone dihedral angles φ and ψ. For a given 2D probability distribution of (φ, ψ) with bin size of 8° × 8°, conformational entropy was estimated as

| (1) |

where pi is the probability of each bin in φ/ψ space, and kB is the Boltzmann constant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Enhanced sampling of the BH3-only protein binding interface in REST simulations

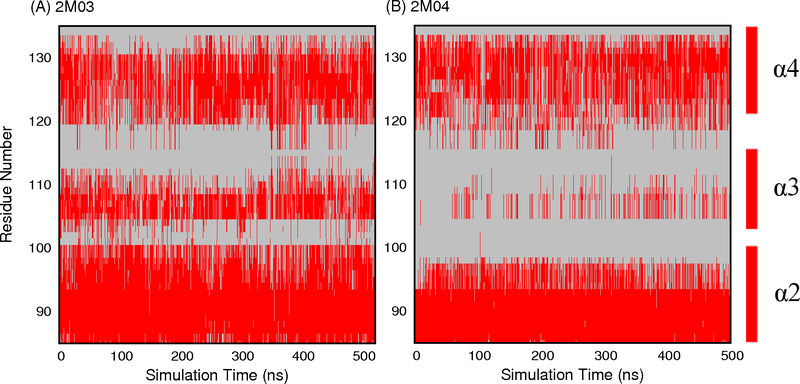

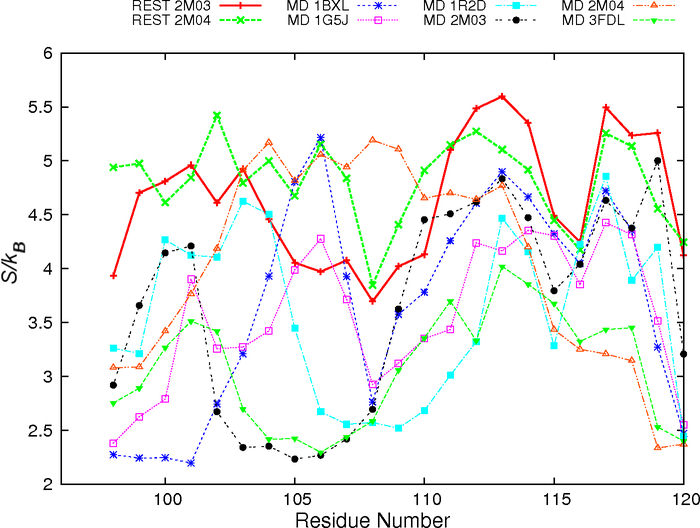

Explicit solvent MD simulations initiated from distinct PDB structures at 300 K only managed to sample very limited conformational spaces near the initial conditions29 (e.g., Figure 2C-D). The ability of REST to enhance the sampling of Bcl-xL interfacial conformation is first evaluated by examining at the secondary structure level. The main structure segment of Bcl-xL that appears to adopt varying conformations is helix α3. During both REST runs, helix α3 underwent numerous helix-coil transitions. As a result, the ensembles sampled at the λ = 1 condition contain mixtures of various helix and coil conformations regardless of the initial PDB structures (Figure 3). The average residue helicity in segment α3 peaks at ~0.75 for simulations initiated from 2M03 and ~0.38 from REST run 2M04 (Figure S2). Even though the convergence is still far from ideal, it is much better than the previous regular MD simulations, where helix α3 remained largely folded after up to 710 ns when initiated from PDB structures (e.g., 1R2D) with fully folded helix29. The improved sampling ability of REST simulations is also evident by examining the backbone φ/ψ space visited by residues in the interfacial region, most of which sampled broader distributions in REST simulations (Figure S3). The peptide conformations appear much less likely to be trapped in local energy minima during REST simulations. As such, residue backbone conformational entropies calculated using Eq. 1 are consistently higher from REST simulations (see Figure 4). Note that, although residues 104–119 in MD simulation of 2M04, and residues 105–106 in MD simulation of 1BXL show higher conformational entropy than in REST simulations, this is most likely due to the lack of stable interfacial helix reforming in these MD simulations29.

Figure 3.

Helicity of residues near the BH3-only protein binding interface as a function of REST simulation time at condition λ = 1. Helical residues are colored in red.

Figure 4.

Residue backbone conformational entropy in the BH3-only protein binding interface of Bcl-xL. The first 300 ns data of REST simulations were discarded. Results from MD simulations are obtained by analyzing trajectories from our previous work29.

The quality and convergence of conformational sampling at the tertiary level was evaluated using PCA analysis. As shown in Figure 2, REST simulations were able to sample much broader conformational space than any of the previous MD runs. Furthermore, conformational spaces sampled by both REST runs appear to have significant overlaps, with run 2M04 sampling a substantially broader region that includes what was sampled by run 2M03. Interestingly, all representative conformational sub-states identified from existing PDB structures, including both ligand-bound and ligand-free states, appear to be visited in both REST simulations (Figure 2A-B). Nonetheless, we note that substantial differences persist between structural ensembles obtained from two REST runs at both secondary and tertiary levels, suggesting the simulations were not fully converged. This highlights the formidable challenges of sampling complex and heterogeneous conformational space of moderately-sized disordered protein segments, particularly in the context of a bigger protein. It probably requires significantly longer REST simulations, or more efficient advanced sampling techniques to further improve the level of convergence in the calculated structural ensembles.

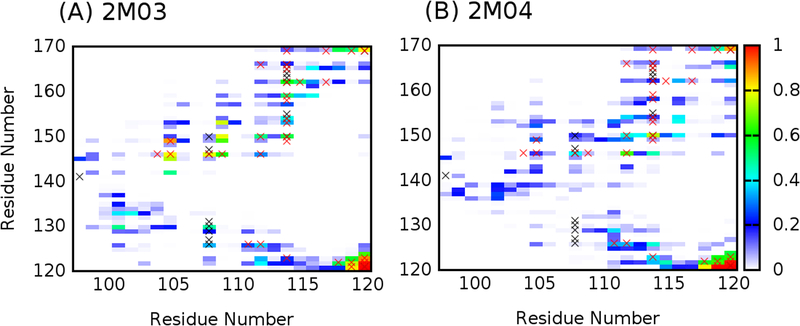

Validation of REST-derived ensembles of unbound Bcl-xL

The reliability of the ensembles generated by REST simulations has been mainly examined by comparing the back-calculated NOE distances with experimental values. As shown in Table 2, all NOE distances for pairs of protons within the BH3-only protein binding interface region obtained from both REST simulations are within ~1 Å of experimentally assigned upper bounds. This is notable since the initial structures of these simulations are significantly different from each other (Figure 1). This implies the local structures of the Bcl-xL interface derived from these two REST simulations are likely realistic. Table 3 and Figure S4 summarize NOE violation analysis for pairs of protons between the BH3-only protein binding interface and the rest of the Bcl-xL protein. For the ensemble derived from REST simulation 2M03, only 3 out of the 30 NOEs are violated by over 1 Å. On the other hand, the ensemble derived from simulation 2M04 yields more violations, with 14 out of 30 NOEs violated by at least 2 Å. This likely reflects the formidable challenge of sampling tertiary packing among different protein segments. Nonetheless, further analysis reveals that the contact maps between residues of the BH3-only protein binding interface region and the rest of the protein are actually similar from both ensembles (Figure 5). The implication is both REST simulations have sampled similar conformational space of the interface; however, the relative probabilities of various conformational substates are not quantitatively converged between two simulations. This notion is also consistent with PCA results showing a high level of overlap in conformational spaces sampled (Figure 2A and B). Importantly, both contact maps are highly consistent with the experimental NOE contact maps (black and red × in Figure 5). Taken together, although REST simulations were not fully converged and some NOE violations persist, the obtained ensembles appear to yield consistent local and tertiary structural features that are likely realistic.

Table 2.

Summary of NOE violation analysis for proton pairs within the BH3-only protein binding interface region of Bcl-xL in the two REST simulations.

| Proton Pairs | RNMR (Å) | (Å) | Violation (Å) | (Å) | Violation (Å) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E98 H | L99 H | 2.67 | 2.76 | 0.09 | 2.40 | - |

| L99 H | R100 H | 2.75 | 2.41 | - | 2.90 | 0.15 |

| L99 H | Y101 H | 3.69 | 4.09 | 0.40 | 4.71 | 1.02 |

| R100 H | Y101 H | 2.75 | 2.35 | - | 2.99 | 0.24 |

| Y101 H | R102 H | 2.96 | 3.10 | 0.14 | 2.81 | - |

| R102 H | R103 H | 4.53 | 2.57 | - | 2.65 | - |

| R103 H | A104 H | 2.85 | 3.14 | 0.29 | 3.33 | 0.48 |

| A104 H | F105 H | 3.10 | 3.24 | 0.14 | 3.24 | 0.14 |

| A104 H | S106 H | 4.36 | 4.77 | 0.41 | 5.40 | 1.04 |

| F105 H | S106 H | 3.27 | 2.40 | - | 3.00 | - |

| F105 H | L108 H | 4.74 | 4.90 | 0.16 | 5.66 | 0.92 |

| S106 H | D107 H | 3.79 | 2.60 | - | 2.25 | - |

| D107 H | L108 H | 3.10 | 2.30 | - | 2.70 | - |

| L108 H | T109 H | 2.92 | 2.62 | - | 2.72 | - |

| L108 H | S110 H | 3.58 | 4.10 | 0.52 | 4.25 | 0.67 |

| T109 H | S110 H | 3.13 | 2.59 | - | 2.44 | - |

| T109 H | Q111 H | 4.00 | 4.20 | 0.20 | 3.99 | - |

| S110 H | L112 H | 4.29 | 4.34 | 0.05 | 4.05 | - |

| Q111 H | L112 H | 2.85 | 2.48 | - | 2.30 | - |

| Q111 H | H113 H | 4.32 | 4.89 | 0.57 | 4.41 | 0.09 |

| L112 H | H113 H | 2.96 | 3.06 | 0.10 | 3.27 | 0.31 |

| H113 H | I114 H | 4.00 | 2.74 | - | 3.12 | - |

| L99 H | L99 QQD | 5.50 | 3.30 | - | 3.06 | - |

| L99 QQD | R100 H | 5.50 | 3.24 | - | 3.04 | - |

| L99 QQD | Y101 H | 5.50 | 4.83 | - | 4.47 | - |

| L108 H | L108 QQD | 4.73 | 3.25 | - | 2.97 | - |

| L112 H | L112 QQD | 5.50 | 3.12 | - | 3.13 | - |

| L112 QQD | H113 H | 5.50 | 2.75 | - | 2.91 | - |

| I114 H | I114 QD1 | 5.17 | 3.11 | - | 3.32 | - |

RNMR is experimentally determined NOE distance. and are calculated NOE-like distance derived from the two REST simulations.

Table 3.

Summary of NOE violation analysis for proton pairs between the BH3-only protein binding interface (left column) and the rest of protein (right column) in the two REST simulations.

| Atom Pairs | RNMR (Å) | (Å) | Violation (Å) | (Å) | Violation (Å) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E98 H | E96 H | 3.79 | 4.28 | 0.49 | 4.36 | 0.57 |

| E98 H | F97 H | 3.06 | 2.67 | - | 2.47 | - |

| E98 H | V141 QQG | 5.41 | 4.76 | - | 5.59 | 0.18 |

| L99 H | F97 H | 3.94 | 4.14 | 0.20 | 4.00 | 0.06 |

| L108 QQD | V126 H | 5.29 | 5.46 | 0.17 | 7.80 | 2.51 |

| L108 QQD | V127 H | 5.29 | 5.61 | 0.32 | 9.20 | 3.91 |

| L108 QQD | E129 H | 5.29 | 4.79 | - | 8.76 | 3.47 |

| L108 QD1 | L130 QD1 | 3.56 | 2.97 | - | 6.21 | 2.65 |

| L108 QD1 | L130 QD2 | 3.56 | 3.38 | - | 6.43 | 2.87 |

| L108 QD2 | L130 QD1 | 3.56 | 2.52 | - | 6.25 | 2.69 |

| L108 QD2 | L130 QD2 | 3.56 | 2.89 | - | 7.14 | 3.58 |

| L108 QQD | L130 H | 5.29 | 3.68 | - | 7.81 | 2.52 |

| L108 QQD | L130 QQD | 2.74 | 2.25 | - | 5.11 | 2.37 |

| L108 QQD | F131 H | 5.29 | 5.71 | 0.42 | 10.57 | 5.28 |

| L108 QD1 | F146 H | 5.50 | 5.82 | 0.32 | 6.11 | 0.61 |

| L108 QD2 | F146 H | 5.50 | 4.76 | - | 5.15 | - |

| L108 QQD | G147 H | 5.29 | 6.11 | 0.82 | 6.17 | 0.88 |

| L108 QQD | L150 H | 5.78 | 5.52 | - | 4.21 | - |

| I114 H | L150 QQD | 5.09 | 3.86 | - | 3.65 | - |

| I114 QD1 | L150 QQD | 2.71 | 2.57 | - | 2.65 | - |

| I114 QD1 | S154 H | 5.94 | 4.07 | - | 7.18 | 1.24 |

| I114 QD1 | V155 H | 5.50 | 5.95 | 0.45 | 7.98 | 2.48 |

| I114 QD1 | L162 QD1 | 3.62 | 3.27 | - | 3.32 | - |

| I114 QD1 | L162 QD2 | 3.62 | 2.69 | - | 3.23 | - |

| I114 QD1 | V163 H | 5.50 | 7.06 | 1.56 | 8.88 | 3.38 |

| I114 QD1 | S164 H | 6.99 | 8.95 | 1.96 | 10.14 | 3.15 |

| I114 QD1 | R165 H | 6.00 | 8.19 | 2.19 | 8.88 | 2.88 |

| I114 QD1 | I166 QD1 | 2.88 | 3.11 | 0.23 | 4.40 | 1.52 |

| Y120 H | Q121 H | 3.31 | 2.90 | - | 2.67 | - |

| Y120 H | W169 HE1 | 3.79 | 3.74 | - | 4.89 | 1.10 |

RNMR is experimentally determined NOE distance restraint. and are calculated NOE-like distances for the two REST simulations.

Figure 5.

Contact probability maps between residues of the BH3-only protein binding interface region (residues 98–120) and the rest of the protein computed from the last 200 ns of REST simulations 2M03 and 2M04, respectively. Contact formation is defined when the minimal heavy-atom-distance between two residues is ≤ 4.2 Å. The probability of forming residue contacts in our simulations is shown in heat map, and contacts detected experimentally from NOE measurements are marked with black (from PDB 2M03) or red × (from PDB 2LPC).

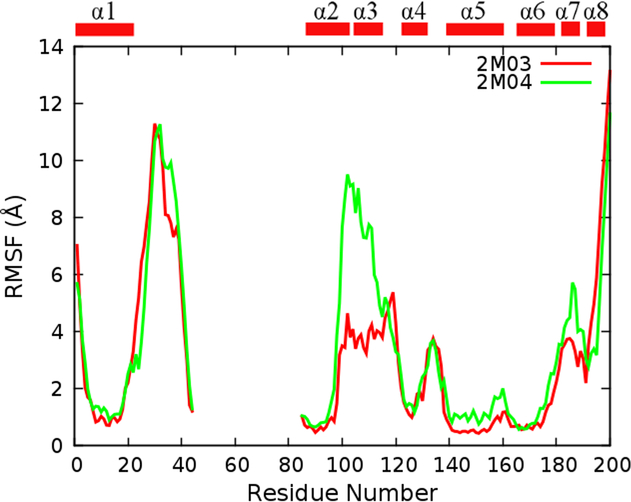

Intrinsic flexibility and structural propensities of the BH3-only protein binding interface

The above analysis has strongly supported that enhanced sampling efficiency of REST has led to structural ensembles that are much better converged and more realistic. This allows us to further examine the conformational properties of the BH3-only protein binding interface of Bcl-xL to understand how they may provide a molecular basis for Bcl-xL recognition. Clearly, the interface is inherently flexible, with root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) values that are much higher than other helical regions and similar to terminal loops and tails (see Figure 6). We note that RMSF values of the interface region derived from REST run 2M04 are larger than those from run 2M03, which may be due to the unfolded initial structure (Figure 1) and thus over-representation of disordered conformations in the final ensemble. Most interfacial residues are highly flexible and could sample both α-helix and extended conformations in the Ramachandra space (Figure S3A and B) and yield large backbone conformational entropy (Figure 4). This is also reflected in Figure S5 that solvent accessible surface area (SASA) of each interfacial residue shows large variance in both simulated ensembles and PDB ensembles. Moreover, packing between the BH3-only protein binding interface and the rest of the protein is not very tight, and many transient contacts could be formed between them (Figure 5). Interestingly, MD and NMR ensembles of unbound Bcl-xL have similar SASA profiles, despite substantial helical contents observed in MD. That is, residual structures do not lead to premature exposure of hydrophobic residues prior to binding (e.g., F105).

Figure 6.

RMSF profiles of Bcl-xL Cα atoms calculated from REST trajectories (not including the first 300 ns data). All structures were superimposed based on Cα atoms of the core region (residues 85–98, 123–127, 140–156, and 162–175) before RMSF calculations.

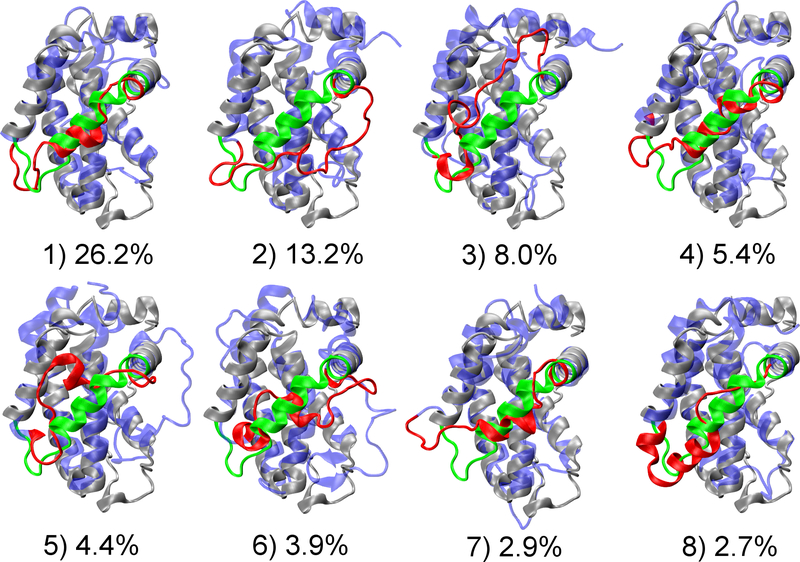

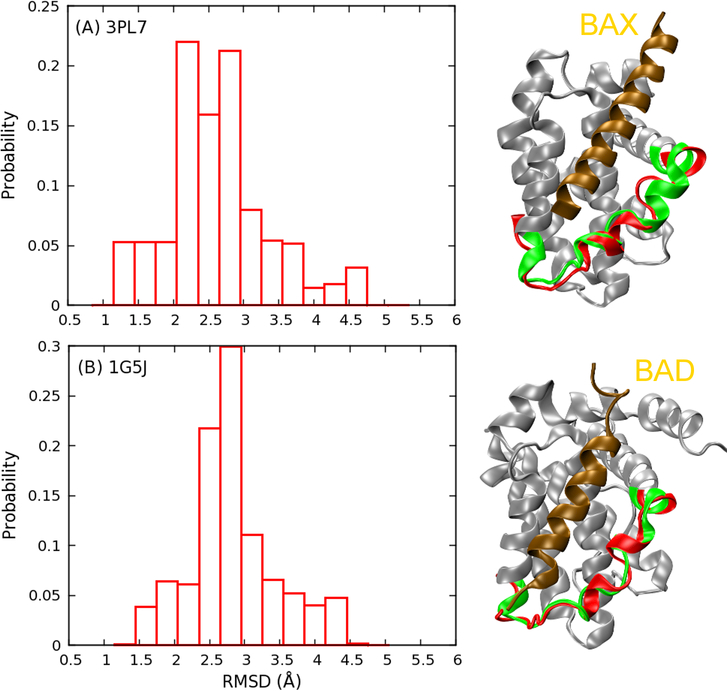

The top eight most populated conformational “substates” identified from the clustering analysis are shown in Figure 7 and Figure S6, which further illustrate the highly heterogeneous nature of the BH3-only protein binding interface of Bcl-xL. The interfacial region could adopt various helical or disordered conformations, and interact with the rest of the protein through different packing modes. Moreover, based on our PCA analysis (Figure 2), which mainly captures the global motion of the interface regions, it’s evident that all previously observed configurations could be visited by the free form of Bcl-xL. Although PC1 and PC2 are not necessarily appropriate reaction coordinates, energy barriers among various free energy basins seem to be mild (~2–3 kcal/mol), suggesting that conformational fluctuations at the BH3-only protein binding interface are likely rapid. For instance, both bound configurations of Bcl-xL in complex with BAX46 (Figure 8A) or BAD47 (Figure 8B) are well represented in the disordered ensemble derived from REST simulations. Although the existence of bound-like conformations in the unbound ensemble does not directly suggest conformational selection-like mechanism48–51 in Bcl-xL binding, accessibility of various bound states even in absence of ligands could facilitate Bcl-xL to respond rapidly to specific binding events, including the observed partial unfolding induced by PUMA binding.

Figure 7.

Central structures and populations of eight largest clusters for the simulated structure ensemble. Initial structure of simulation 2M03 is shown in grey cartoon, with the BH3-only protein binding interface highlighted in green. Central structure of each cluster is shown in blue, with the interfacial region colored in red. Clusters 1, 4, 7 and 8 are from 2m03 simulation, and 2, 3, 5 and 6 from 2m04 simulation.

Figure 8.

Probability distribution of interfacial Cα RMSD of the Bcl-xL structural ensemble derived from REST simulation 2M03 with respect to two PDB structures: (A) 3PL7 chain A (BAX bound form) and (B) 1G5J (BAD bound form). Representative low RMSD structures are shown. Bcl-xL in 3PL7 and 1G5J are colored in gray, with the BH3-only protein binding interface highlighted in green and bound BH3-peptide shown in ochre. Representative configurations of the interface sampled in REST are shown in red.

CONCLUSIONS

Previous NMR and biochemical studies have demonstrated that anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL undergoes local unfolding upon specific binding to the BH3-only protein PUMA, which in turn disrupts the interaction between Bcl-xL and tumor suppressor p53 and activates apoptosis27. However, the detailed mechanisms of such regulated unfolding of Bcl-xL have not been fully understood yet. Our previous studies have suggested that substantial intrinsic structure heterogeneity exists at the BH3-only protein binding interface of Bcl-xL29, which could provide a general mechanism for supporting coupled binding, folding and unfolding in Bcl-xL recognition. We have leveraged enhanced sampling capability of REST to further characterize the conformational properties of unbound Bcl-xL at atomistic level in explicit solvent. Independent REST simulations initiated from two contrasting initial PDB structures yield structural ensembles that are not only much better converged but also highly consistent with available NMR data. The new simulations further support the notion that the binding interface of Bcl-xL has significant and inherent conformational heterogeneity. Intriguingly, the new results reveal that all previously observed conformations of Bcl-xL, including both bound and unbound states, are well represented in the unbound ensemble of Bcl-xL, and their interconversion appear to be rapid and involve small free energy barriers. Altogether, it is highly plausible that such inherent structural heterogeneity and plasticity at the binding interface is crucial for Bcl-xL to undergo rapid structural rearrangement and respond sensitively to various binding ligands for downstream signaling. Such a general molecular mechanism may also be relevant for understanding other emerging cases of regulated unfolding in cellular signaling and regulation23.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Dr. Huan-Xiang Zhou for assistance with the REST protocol. The computing was performed using the Beocat cluster at Kansas State University and Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) facilities (TG-MCB140210). This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM114300).

REFERENCES

- 1.Dyson HJ; Wright PE, Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 2005, 6 (3), 197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uversky VN; Oldfield CJ; Dunker AK, Showing your id: Intrinsic disorder as an id for recognition, regulation and cell signaling. J Mol Recognit 2005, 18 (5), 343–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen J, Towards the physical basis of how intrinsic disorder mediates protein function. Arch Biochem Biophys 2012, 524 (2), 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright PE; Dyson HJ, Intrinsically unstructured proteins: Re-assessing the protein structure-function paradigm. J Mol Biol 1999, 293 (2), 321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunker AK; Obradovic Z; Romero P; Garner EC; Brown CJ, Intrinsic protein disorder in complete genomes. Genome informatics. Workshop on Genome Informatics 2000, 11, 161–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xue B; Dunker AK; Uversky VN, Orderly order in protein intrinsic disorder distribution: Disorder in 3500 proteomes from viruses and the three domains of life. Journal of biomolecular structure & dynamics 2012, 30 (2), 137–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunker AK; Brown CJ; Lawson JD; Iakoucheva LM; Obradovic Z, Intrinsic disorder and protein function. Biochemistry 2002, 41 (21), 6573–6582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright PE; Dyson HJ, Intrinsically disordered proteins in cellular signalling and regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 2015, 16 (1), 18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iakoucheva LM; Brown CJ; Lawson JD; Obradovic Z; Dunker AK, Intrinsic disorder in cell-signaling and cancer-associated proteins. J Mol Biol 2002, 323 (3), 573–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Babu MM; van der Lee R; de Groot NS; Gsponer J, Intrinsically disordered proteins: Regulation and disease. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2011, 21 (3), 432–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smock RG; Gierasch LM, Sending signals dynamically. Science 2009, 324 (5924), 198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boehr DD; Nussinov R; Wright PE, The role of dynamic conformational ensembles in biomolecular recognition (vol 5, pg 789, 2009). Nature chemical biology 2009, 5 (12), 954–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiti F; Dobson CM, Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Annu Rev Biochem 2006, 75, 333–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu HC; Chung SS; Fornili A; Fraternali F, Anatomy of protein disorder, flexibility and disease-related mutations. Frontiers in molecular biosciences 2015, 2, 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vacic V; Markwick PR; Oldfield CJ; Zhao X; Haynes C; Uversky VN; Iakoucheva LM, Disease-associated mutations disrupt functionally important regions of intrinsic protein disorder. PLoS Comput Biol 2012, 8 (10), e1002709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gsponer J; Futschik ME; Teichmann SA; Babu MM, Tight regulation of unstructured proteins: From transcript synthesis to protein degradation. Science 2008, 322 (5906), 1365–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vavouri T; Semple JI; Garcia-Verdugo R; Lehner B, Intrinsic protein disorder and interaction promiscuity are widely associated with dosage sensitivity. Cell 2009, 138 (1), 198–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uversky VN, Intrinsic disorder-based protein interactions and their modulators. Curr Pharm Design 2013, 19 (23), 4191–4213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teilum K; Olsen JG; Kragelund BB, Functional aspects of protein flexibility. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS 2009, 66 (14), 2231–2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright PE; Dyson HJ, Linking folding and binding. Curr Opin Struc Biol 2009, 19 (1), 31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shammas SL; Crabtree MD; Dahal L; Wicky BIM; Clarke J, Insights into coupled folding and binding mechanisms from kinetic studies. J. Biol. Chem 2016, 291 (13), 6689–6695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogers JM; Oleinikovas V; Shammas SL; Wong CT; De Sancho D; Baker CM; Clarke J, Interplay between partner and ligand facilitates the folding and binding of an intrinsically disordered protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2014, 111 (43), 15420–15425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitrea DM; Kriwacki RW, Regulated unfolding of proteins in signaling. Febs Lett 2013, 587 (8), 1081–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Czabotar PE; Lessene G; Strasser A; Adams JM, Control of apoptosis by the bcl-2 protein family: Implications for physiology and therapy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 2014, 15 (1), 49–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green DR; Kroemer G, Cytoplasmic functions of the tumour suppressor p53. Nature 2009, 458 (7242), 1127–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Follis AV; Llambi F; Ou L; Baran K; Green DR; Kriwacki RW, The DNA-binding domain mediates both nuclear and cytosolic functions of p53. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2014, 21 (6), 535–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Follis AV; Chipuk JE; Fisher JC; Yun M-K; Grace CR; Nourse A; Baran K; Ou L; Min L; White SW, et al. , Puma binding induces partial unfolding within bcl-xl to disrupt p53 binding and promote apoptosis. Nat Chem Biol 2013, 9 (3), 163–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hinds M; Smits C; Fredericks-Short R; Risk J; Bailey M; Huang D; Day C, Bim, bad and bmf: Intrinsically unstructured bh3-only proteins that undergo a localized conformational change upon binding to prosurvival bcl-2 targets. Cell Death Differ. 2006, 14 (1), 128–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu XR; Beugelsdijk A; Chen JH, Dynamics of the bh3-only protein binding interface of bcl-xl. Biophys J 2015, 109 (5), 1049–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu P; Kim B; Friesner RA; Berne BJ, Replica exchange with solute tempering: A method for sampling biological systems in explicit water. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2005, 102 (39), 13749–13754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang LL; Friesner RA; Berne BJ, Replica exchange with solute scaling: A more efficient version of replica exchange with solute tempering (rest2). J Phys Chem B 2011, 115 (30), 9431–9438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugita Y; Okamoto Y, Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding. Chem Phys Lett 1999, 314 (1–2), 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hansmann UHE, Parallel tempering algorithm for conformational studies of biological molecules. Chem. Phys. Lett 1997, 281 (1–3), 140–150. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pang X; Zhou HX, Disorder-to-order transition of an active-site loop mediates the allosteric activation of sortase a. Biophys J 2015, 109 (8), 1706–1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang K; Garcia AE, Acceleration of lateral equilibration in mixed lipid bilayers using replica exchange with solute tempering. J Chem Theory Comput 2014, 10 (10), 4264–4272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terakawa T; Kameda T; Takada S, On easy implementation of a variant of the replica exchange with solute tempering in gromacs. Journal of computational chemistry 2011, 32 (7), 1228–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stirnemann G; Sterpone F, Recovering protein thermal stability using all-atom hamiltonian replica-exchange simulations in explicit solvent. J Chem Theory Comput 2015, 11 (12), 5573–5577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pronk S; Pall S; Schulz R; Larsson P; Bjelkmar P; Apostolov R; Shirts MR; Smith JC; Kasson PM; van der Spoel D, et al. , Gromacs 4.5: A high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics 2013, 29 (7), 845–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bussi G, Hamiltonian replica exchange in gromacs: A flexible implementation. Mol Phys 2014, 112 (3–4), 379–384. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hornak V; Abel R; Okur A; Strockbine B; Roitberg A; Simmerling C, Comparison of multiple amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins 2006, 65 (3), 712–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Darden T; York D; Pedersen L, Particle mesh ewald - an n.Log(n) method for ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys 1993, 98 (12), 10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hess B; Bekker H; Berendsen HJC; Fraaije JGEM, Lincs: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. Journal of computational chemistry 1997, 18 (12), 1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fletcher CM; Jones DNM; Diamond R; Neuhaus D, Treatment of noe constraints involving equivalent or nonstereoassigned protons in calculations of biomacromolecular structures. Journal of biomolecular NMR 1996, 8 (3), 292–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McDowell C; Chen JL; Chen JH, Potential conformational heterogeneity of p53 bound to s100b(beta beta). J Mol Biol 2013, 425 (6), 999–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wysoczanski P; Mart RJ; Loveridge EJ; Williams C; Whittaker SB-M; Crump MP; Allemann RK, Nmr solution structure of a photoswitchable apoptosis activating bak peptide bound to bcl-xl. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2012, 134 (18), 7644–7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Czabotar PE; Lee EF; Thompson GV; Wardak AZ; Fairlie WD; Colman PM, Mutation to bax beyond the bh3 domain disrupts interactions with pro-survival proteins and promotes apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem 2011, 286 (9), 7123–7131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petros AM; Nettesheim DG; Wang Y; Olejniczak ET; Meadows RP; Mack J; Swift K; Matayoshi ED; Zhang H; Thompson CB, et al. , Rationale for bcl-xl/bad peptide complex formation from structure, mutagenesis, and biophysical studies. Protein science : a publication of the Protein Society 2000, 9 (12), 2528–2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bohnuud T; Kozakov D; Vajda S, Evidence of conformational selection driving the formation of ligand binding sites in protein-protein interfaces. PLoS Comput Biol 2014, 10 (10), e1003872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kjaergaard M; Teilum K; Poulsen FM, Conformational selection in the molten globule state of the nuclear coactivator binding domain of cbp. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2010, 107 (28), 12535–12540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Knott M; Best RB, A preformed binding interface in the unbound ensemble of an intrinsically disordered protein: Evidence from molecular simulations. PLoS Comput. Biol 2012, 8 (7), e1002605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ganguly D; Zhang W; Chen J, Synergistic folding of two intrinsically disordered proteins: Searching for conformational selection. Molecular BioSystems 2012, 8 (1), 198–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.