Abstract

Coding variants represent many of the strongest associations between genotype and phenotype, however they exhibit inter-individual differences in effect, termed variable penetrance. Here, we study how cis-regulatory variation modifies the penetrance of coding variants. Using functional genomic and genetic data from GTEx, we observed that in the general population, purifying selection has depleted haplotype combinations predicted to increase pathogenic coding variant penetrance. Conversely, in cancer and autism patients, we observed an enrichment of penetrance increasing haplotype configurations for pathogenic variants in disease implicated genes, providing evidence that regulatory haplotype configuration of coding variants affects disease risk. Finally, we experimentally validated this model by editing a Mendelian SNP using CRISPR/Cas9 on distinct expression haplotypes with the transcriptome as a phenotypic readout. Our results demonstrate that joint regulatory and coding variant effects are an important part of the genetic architecture of human traits and contribute to modified penetrance of disease-causing variants.

Introduction

Variable penetrance and variable expressivity are common phenomena that cause individuals carrying the same variant to often display highly variable symptoms, even in the case of Mendelian and other severe diseases driven by rare variants with strong effects on phenotype 1. For our purposes, we use the term variable penetrance as a joint description of both variable expressivity (severity of phenotype) and penetrance (proportion of carriers with phenotype). These phenomena are a key challenge for understanding how genetic variants manifest in human traits, and a major practical caveat for the prognosis of an individual’s disease outcomes based on their genetic data. However, the causes and mechanisms of variable penetrance are poorly understood. In addition to environmental modifiers of genetic effects, a potential cause of variable penetrance involves other genetic variants with additive or epistatic modifier effects 2. While some studies have successfully mapped genetic modifiers of, for example, BRCA variants in breast cancer 3 and RETT variants in Hirschsprung’s disease 4, genome-wide analysis of pairwise interactions between variants has proven to be challenging in humans. In part, this is because exhaustive pairwise testing of genome-wide interactions typically lacks power and is easily affected by confounders 5, and a targeted analysis of a specific variant or gene that is strongly implicated in rare disease typically suffers from a low number of carriers. However, emerging large data sets with functional genomic and genetic data from disease cohorts now enable the genome-wide study of mechanistically justified hypotheses of how combinations of genetic variants may have joint effects on disease risk.

In this study, we analyze how regulatory variants in cis may modify the penetrance of coding variants in their target genes via the joint effects of these variants on the final dosage of functional gene product, depending on their haplotype combination (Figs. 1, S1). This phenomenon has been demonstrated to affect penetrance of disease-predisposing variants in individual loci 6–9, explored in early functional genomic datasets 10,11, and expression modifiers are known in model organisms 12. However, genome-wide evidence of regulatory modifiers of disease risk driven by coding variants has been lacking, alongside a generally applicable theoretical framework and analytical methods to study this phenomenon. This means that while potentially important, this phenomenon is often not addressed in genome wide association studies of common disease. In this work, we use population-scale functional genomics and disease cohort data sets to show that genetic regulatory modifiers of pathogenic coding variants affect disease risk. Furthermore, we use genome editing with CRISPR/Cas9 to demonstrate an experimental approach for studying the role of regulatory variants as modifiers of coding variant penetrance. We focus on rare pathogenic coding variants from exome and genome sequencing data that provide the best characterized group of variants with strong phenotypic effects, and common regulatory variants affecting gene expression or splicing. Thus, our analysis integrates these traditionally separate fields of human genetics by considering joint effects that different types of mutations have on gene function.

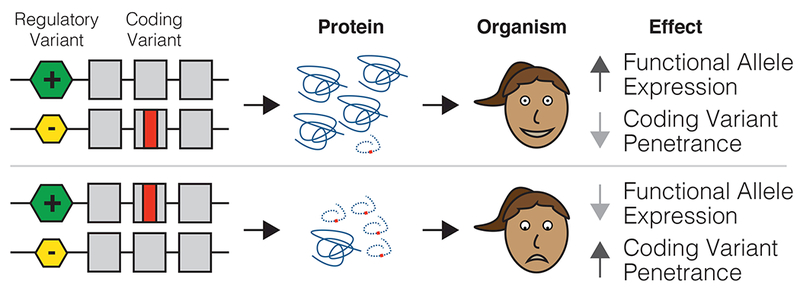

Figure 1. Regulatory variants as modifiers of coding variant penetrance.

The hypothesis of this study is illustrated with an example where an individual is heterozygous for both a regulatory variant and a pathogenic coding variant. The two possible haplotype configurations would result in either decreased penetrance of the coding variant if it was on the lower expressed haplotype, or increased penetrance of the coding variant if it was on the higher expressed haplotype. See Supplementary Figure 1 for a quantitative description of the model.

Results

Purifying selection acts on haplotype combinations

First, we tested the hypothesis that purifying selection should deplete haplotype combinations that increase the penetrance of pathogenic coding variants from the general population. To accomplish this, we analyzed data from the Genotype Tissue Expression (GTEx) project which is representative of the general population in that it lacks individuals with severe genetic disease 13. This consists of genotype and RNA-sequencing data of 7,051 samples across 44 tissues from the 449 individuals with exome sequencing and SNP array data of the GTEx v6p release 14. Throughout this study, we defined the predicted pathogenicity of variants using their CADD score, which incorporates a wide breadth of annotations, including conservation and protein structure 15. We used the authors’ suggested cutoff of 15 for defining potentially pathogenic variants, which is the median CADD score across all possible canonical splice site and missense variants in the human genome (see Methods – Variant Annotation).

We first measured the regulatory haplotype of coding variants using allelic expression (AE) data, which captures cis effects of both expression and splice regulatory variation at the individual level. We employed multiple approaches to account for issues of mapping bias, which often affect allelic expression studies (see Methods – GTEx Allelic Expression Analysis) 16. In the modified penetrance model, purifying selection should result in a depletion of pathogenic variants on higher expressed or exon including haplotypes. For each of the 44 GTEx tissues we calculated the expression of coding variant minor alleles using allelic fold change (aFC) 17, and compared the expression of missense variants to allele frequency (AF) matched synonymous controls. Supporting our hypothesis, the minor alleles of missense variants showed reduced allelic expression that was proportional to their predicted pathogenicity (Fig. 2a). Across tissues, rare (AF < 1%) pathogenic (CADD > 15) missense variants showed a significant (p = 4.57e-9) 0.70% reduction of allelic expression compared to synonymous controls, but rare benign (CADD < 15) missense variants did not (p = 0.388) (Figs. 2b, S2a-b). This suggests that in the general population, pathogenic variants are depleted from higher expressed or exon including regulatory haplotypes. We also performed this analysis using polyPhen alone to define coding variant pathogenicity to ensure that our results were not biased by the additional features used by CADD and found that they were consistent (Supplementary Figure 2c).

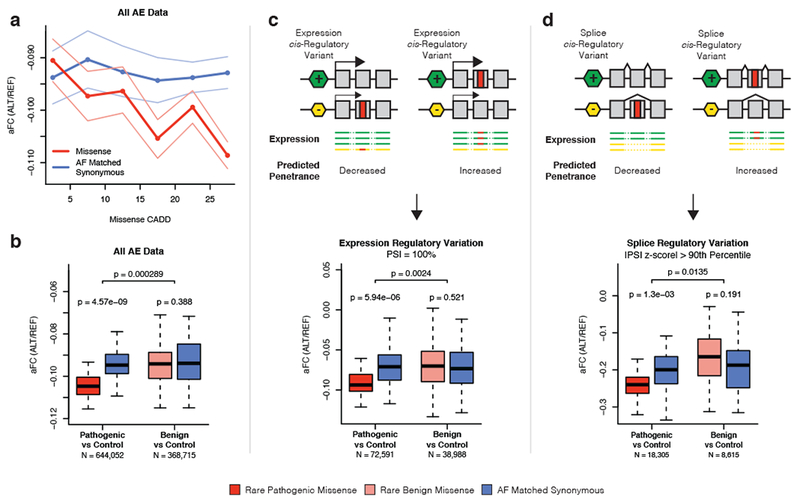

Figure 2. Analysis of regulatory effects at the individual level reveals that pathogenic coding variants are depleted from higher expressed and exon including regulatory haplotypes in the general population.

a) Allelic fold change (aFC) of rare (AF < 1%) missense and AF matched synonymous variants in bins of 5 CADD PHRED with 95% confidence interval across GTEx tissues. N = 1,012,767 independent ASE measurements. b) Boxplot of mean aFC across each of the 44 GTEx tissues calculated for rare pathogenic missense (CADD > 15), rare benign missense (CADD < 15), and allele frequency matched synonymous controls. c) Mean aFC across tissues calculated using only variants found in exons where the sample has 100% exon inclusion, as measured by percent spliced in (PSI), which removes allelic effects arising from splice regulatory variation. d) Mean aFC across tissues calculated using only variants found in exons where the sample has substantial variation in exon inclusion compared to the population, as defined by |PSI z-score| > 90th percentile across all exons, which enriches for allelic effects caused by splice regulatory variation. The total number (N) of variant aFC measurements across all tissues for pathogenic and benign variants is indicated. P-values are generated by comparing mean aFC of missense variants versus AF matched synonymous controls across tissues using a two-sided paired Wilcoxon signed rank test. For boxplots, bottom whisker: Q1–1.5*IQR, top whisker: Q3+1.5*IQR, box: IQR, center: median, and outliers are not plotted for ease of viewing. See Supplementary Figure 2 for related analyses.

In order to study whether this pattern is driven by regulatory variation affecting expression or splicing, which both manifest in allelic expression, we partitioned the coding variants into two groups. To accomplish this, we quantified exon inclusion in each GTEx sample using RNA-seq reads spanning exon junctions to produce a measure of percent spliced in (PSI) for each exon in each sample 18. To isolate the effects of regulatory variation, we analyzed allelic expression only for variants that were found in an exon with 100% inclusion in that individual. As before, rare pathogenic missense variants had significantly reduced expression as compared to synonymous controls (p = 5.94e-6; 1.56% reduction), but rare benign variants did not (p = 0.521), suggesting that pathogenic variants are less likely to accumulate on higher expressed regulatory haplotypes (Fig. 2c). To isolate the effects of splice regulatory variation, we analyzed allelic expression of variants in exons where the sample had substantial deviation in exon inclusion from the population mean. To define these exons, for each exon, a population normalized PSI z-score was produced for each sample allowing for exon inclusion at the sample level to be compared to others (Supplementary Figure 2e). When measuring allelic expression of variants found in the top 10% of sample exons by absolute PSI z-score, we again observed that rare pathogenic missense variants had significantly reduced expression as compared to synonymous controls (p = 1.3e-3; 2.00% reduction), but rare benign variants did not (p = 0.191). This suggests that pathogenic variants are less likely to accumulate on haplotypes where the corresponding exon is more likely to be included in transcripts (Fig. 2d). In all analyses, pathogenic variants had significantly reduced expression versus AF matched synonymous controls as compared to benign variants (Supplementary Figure 2d). Altogether, these analyses of allelic expression data suggest that in a cohort representative of the general population, pathogenic coding variants less frequently exist in high-penetrance regulatory haplotype combinations, as would be expected under the modified penetrance model.

While allelic expression paired with splice quantification provides a powerful functional readout of latent regulatory variants acting on a gene in each individual, the phenomenon of modified penetrance can also be studied from genetic data alone by analyzing phased haplotypes of coding variants and regulatory variants identified by expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) mapping in cis. Our hypothesis is that in pathogenic coding variant heterozygotes, eQTL-mediated lower expression of the haplotype carrying the “wildtype”, major coding allele increases the penetrance of the rare allele, and vice versa (Figs. 3a, S1). To study this, we developed a test for regulatory modifiers of penetrance that uses phased genetic data (see Methods – Test for Regulatory Modifiers of Penetrance Using Phased Genetic Data). Briefly, for each rare coding variant heterozygote, we test whether the major coding allele is on the lower expressed eQTL haplotype (Supplementary Figure 3a) and determine if this occurs more or less frequently than would be expected under the null based on eQTL frequencies in the population studied (Supplementary Figure 3b). Using simulated data, we found that our test was well calibrated under the null while still being sensitive to changes in haplotype configuration (Supplementary Figure 3c-d).

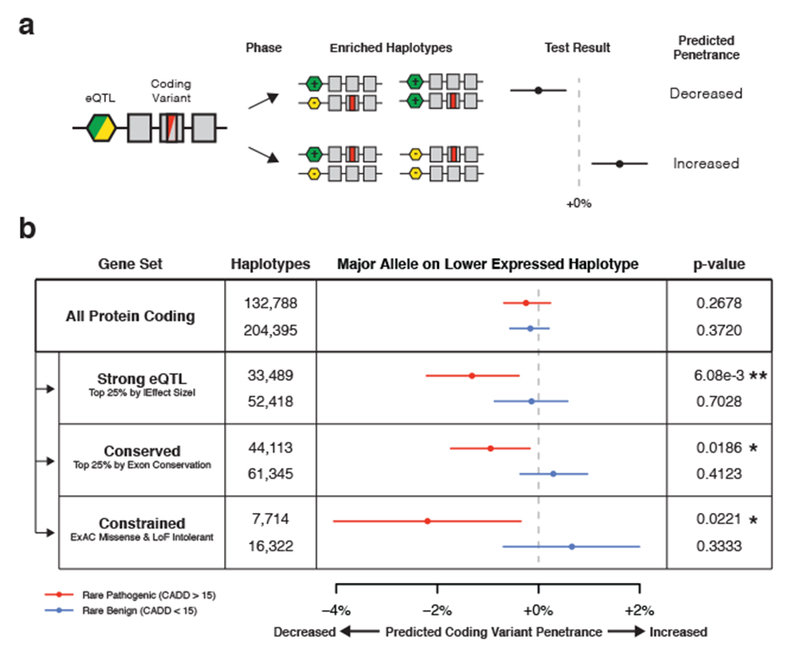

Figure 3. eQTL haplotype configurations that are predicted to increase pathogenic coding variant penetrance are depleted i the genomes of GTEx individuals.

a) Phased genetic data can be used to produce haplotype configurations between regulatory variation identified using expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) mapping and coding variant heterozygotes. Decreased expression of major coding alleles mediated by an eQTL could result in increased penetrance of the minor coding allele and vice-versa (Supplementary Figure 1). The observed frequency that major coding variant alleles are on lower expressed eQTL haplotypes is tested against a null distribution, which accounts for eQTL frequencies and assumes that coding variants occur on random haplotypes and in random individuals. The statistic indicates the percentage increase or decrease compared to the null, where a positive value suggests increased penetrance and a negative value decreased penetrance. b) Test for regulatory modifiers of coding variant penetrance using 620 GTEx v7 population and read-backed phased whole genomes and GTEx v6p eQTLs, applied to rare (MAF < 1%) pathogenic (CADD > 15, including missense, splice, and stop gained), and rare benign (CADD < 15, including synonymous and missense) SNPs for different gene sets. Median estimates, 95% confidence intervals, and two-sided empirical p-values were generated using 100,000 bootstraps. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01. See Methods - Test for Regulatory Modifiers of Penetrance Using Phased Genetic Data and Supplementary Figure 3 for description and benchmarking of the test, and a description of the gene sets used.

To analyze whether the distribution of coding variants on cis-eQTL haplotypes in GTEx showed signs of selection against increased penetrance, we produced a large set of haplotype phased genetic data from GTEx v7, where 30× whole genome sequencing of 620 individuals was available. This was obtained from population based phasing paired with read-backed phasing using DNA-seq reads 19 and RNA-seq reads 20 from up to 38 tissues for a single individual. This allowed us to analyze the haplotypes of 221,487 rare (MAF < 1%) coding variants at thousands of genes with known common (MAF > 5%) eQTLs from GTEx v6p 14 (Supplementary Table 1). Using our test for regulatory modifiers of penetrance, we did not observe any significant evidence of reduced penetrance of rare potentially pathogenic variants when all protein coding genes were analyzed together (p = 0.268). However, we hypothesized that genes might be under differing selective pressure with respect to this phenomenon, so we stratified our analysis based on eQTL effect size, gene conservation, and coding constraint. We observed a significant negative correlation between the predicted penetrance of rare potentially pathogenic variants and both eQTL effect size (ρ = −0.229, p = 0.0224) and gene conservation (ρ = −0.217, p = 0.0304), while no significant correlation was observed for benign variants (Supplementary Figure 4). We quantified this effect, and found that pathogenic variants in genes with strong eQTLs (top 25% by |effect size|) had a significant (p = 6.08e-3) decrease of 1.32% in the frequency of haplotypes where the major coding allele was on the lower expressed haplotype expressed than would be expected under the null, while no effect was seen for benign variants (p = 0.703) (Fig. 3b). Similarly, we also observed a significant reduction of predicted penetrance of rare potentially pathogenic variants (p = 0.0186) but not benign variants (p = 0.412) in conserved genes (top 25% by median exon base conservation). Finally, we observed the strongest effect at genes that were loss of function and missense intolerant defined using ExAC (−2.20%, p = 0.0221) 21,22, while no effect was seen for benign variants (p = 0.333).

Altogether, combined with observations from functional data of allelic expression, these results suggest that joint effects between regulatory and coding variants have shaped human genetic variation in the general population through purifying selection depleting haplotype combinations where cis-regulatory variants increase the penetrance of pathogenic coding variants (Supplementary Figure 1). These patterns are significant and consistent, although the genome-wide magnitude of their effects is not strong. However, since our results indicate that regulatory modifiers of penetrance affect primarily pathogenic coding variants, stronger cis-regulatory variants, and both conserved and constrained genes, genome-wide analysis likely ends up diluting a signal that may be strong and phenotypically relevant for a subset of genes and variants.

Regulatory modifiers of penetrance affect disease risk

We next sought to investigate whether regulatory modifiers of penetrance affect disease risk in patients. This would manifest as patients having an overrepresentation of regulatory haplotype configurations that increase penetrance of putatively disease-causing coding variants as compared to controls, where an enrichment of low-penetrance combinations is expected. Importantly, our test is calibrated to eQTL allele frequencies separately in case and control individuals, so that it measures only differences in haplotype configurations and not eQTL frequency between the populations. To test this hypothesis, we applied our genetic test for regulatory modifiers of penetrance to two large disease cohorts in cancer and autism. These diseases have a known contribution from rare coding variants in hundreds of disease-implicated genes, as well as large accessible genomic data sets that include data of rare coding variants and common variants genome-wide.

To study the role of regulatory modifiers of penetrance in germline cancer risk we used population and read-backed phased germline variants (Supplementary Figure 5b) from whole genome sequencing of 615 Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) individuals (Supplementary Table 2) 23. Whole genome sequenced, population and read-backed phased genotypes from 620 GTEx v7 individuals were used as controls (Supplementary Figure 5a). We analyzed tumor suppressor genes (see Methods – Gene Sets) that are known to harbor germline risk variants for cancer, often with a dosage-sensitive disease mechanism 24. To study autism spectrum disorder (ASD) we used transmission phased exome and imputed SNP array genotype data (Supplementary Figure 5c-d) from the Simons Simplex Collection of 2,600 simplex families with one child with autism, their parents, and any unaffected siblings 25–27. When available, one unaffected sibling per family was used as a control. We analyzed a broad set of genes spanning multiple sources that have been previously implicated in ASD 27,28 (see Methods – Gene Sets).

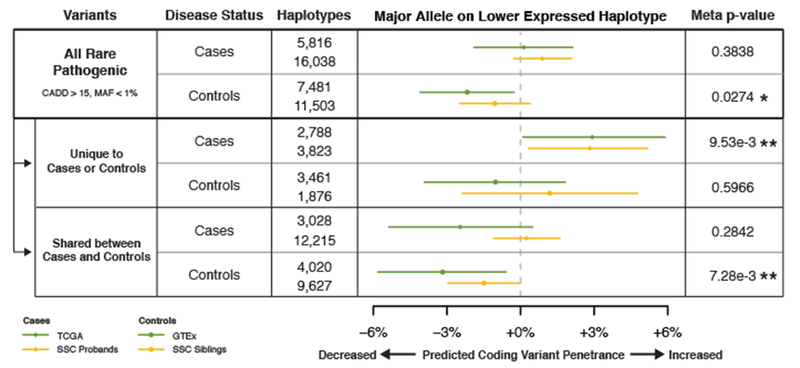

Our genetic test for regulatory modifiers of penetrance was applied to these data sets, first separately and then jointly, since we were testing the same hypothesis in both the cancer and autism cohorts. We stratified our analysis by the sharing of coding variants between cases and controls, with coding variants observed only in cases likely having the highest proportion of true disease-contributing variants, and with a decreasing proportion of variants contributing to disease among those observed both in cases and controls, and those only in controls (Fig. 4). Using this approach, we found that in disease associated genes, case-specific rare pathogenic variants were significantly enriched for haplotype configurations where the major allele was on the lower expressed haplotype (p = 9.53e-3), with control-specific variants showing no enrichment, as expected (p = 0.597). When analyzing shared variants, we found that in control individuals these were enriched for haplotype configurations where the major allele was on the higher expressed haplotype (p = 7.28e-3) – suggesting a potentially decreased penetrance of some disease-contributing variants – but a consistent or significant effect was not observed in cases for this group of variants (p = 0.284). No significant haplotype configuration enrichment in either cases or controls was found for rare benign variants at disease associated genes (Supplementary Figure 6a) or pathogenic variants at control genes matched for coding variant frequency (Supplementary Figure 6b). All individual cohort results are presented in Supplementary Table 3, with generally consistent patterns between the autism and cancer cohorts. Altogether these results suggest that individuals with disease have an enrichment of harmful expression haplotype configurations that are predicted to increase coding variant penetrance, whereas unaffected individuals have an enrichment of protective configurations predicted to decrease coding variant penetrance. We expect that the true magnitude of the biological effect is diluted in our analysis due to false positives in the disease gene sets, only a subset of the potentially pathogenic variants studied being disease relevant, and modified penetrance affecting only a subset of genes. Nevertheless, the significant disease association of specific regulatory and coding variant configurations across two independent disease cohorts indicates a role for modified penetrance of coding variants by regulatory variation in both cancer and autism spectrum disorder.

Figure 4. eQTL haplotype configurations that are predicted to increase pathogenic coding variant penetrance are enriched in individuals with cancer and autism spectrum disorder.

Analysis of eQTL and coding variant haplotype configurations in cases and controls for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and cancer, using the top GTEx v6p eQTL per gene by p-value across all tissues. For ASD analysis, haplotype configurations generated from transmission phased genetic data of 2,304 SSC ASD affected probands (cases) and 1,712 of their unaffected siblings (controls) were used, and haplotypes were analyzed at ASD implicated genes. For cancer analysis, haplotype configurations generated from population and read-back phased germline whole genomes of 615 TCGA individuals (cases) and 620 whole genomes of v7 GTEx individuals (controls) were used, and haplotypes were analyzed at tumor suppressor genes. To enrich for putatively disease-causing variants, results were stratified based on if variants were restricted to cases or controls, or shared between both. Median estimates and 95% confidence intervals were generated using 100,000 bootstraps, and two-sided empirical p-values were generated from these confidence intervals and combined between cohorts using Fisher’s method to produce meta p-values (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01). See Methods – Gene Sets for description of gene sets used, Supplementary Figure 5 for description of eQTL coding variant haplotypes used for the analysis, Supplementary Figure 6 for results from benign variants and control genes, and Supplementary Table 3 for the full table of results, including individual cohort level p-values.

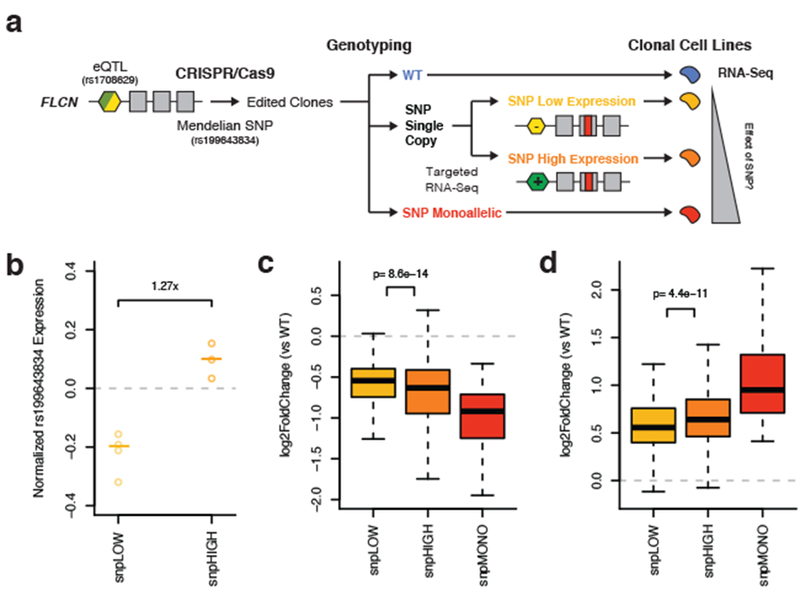

Experimental demonstration of a regulatory modifier effect

Our population scale analyses provide observational evidence that regulatory modifiers of penetrance play a role in the genetic architecture of human traits. We next sought to demonstrate an experimental approach for testing this hypothesis for a specific gene by using CRISPR/Cas9 to introduce a coding variant on distinct regulatory haplotypes, followed by quantification of its penetrance from a cellular readout. Such a framework will be useful for future studies that aim to validate single candidate genes from genome wide analyses. Our finding that modified penetrance of germline variants by eQTLs may be involved in cancer risk lead us to study a missense SNP (rs199643834, Lys508Arg) in the tumor suppressor gene FLCN which encodes for the protein folliculin and has a common eQTL in most GTEx v6p tissues 14. This SNP causes the Mendelian autosomal dominant disease Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome 29 that results in characteristic benign skin tumors, lung cysts, and cancerous kidney tumors and shows variable penetrance 30. We edited the SNP in a fetal embryonic kidney cell line (293T), which is triploid and harbors a single copy of a common (1000 Genomes AF = 0.428) loss of expression eQTL (rs1708629) located in the 5’ UTR of the gene 14,31. This variant is among the most significant variants for the FLCN eQTL signal, overlaps promoter marks across multiple tissues, and alters motifs of multiple transcription factors 32, thus being a strong candidate for the causal regulatory variant of the FLCN eQTL (Supplementary Figure 7a). We recovered monoclonal cell lines, genotyped them by targeted DNA-seq and performed targeted RNA-seq of the edited SNP (Figs. 5a, S6b, Supplementary Table 4). Allelic expression analysis showed that the haplotypes in the cell line are indeed expressed at different levels, likely driven by rs1708629 or another causal variant tagged by it, and the allelic expression patterns allowed phasing of the coding variant with the eQTL (Fig. 5b). In this way, we obtained four clones with a single copy of the Mendelian variant on the lower expressed haplotype (snpLOW), three clones with a single copy on the higher expressed haplotype (snpHIGH), two monoallelic clones with three copies of the alternative allele of rs199643834 (Supplementary Figure 7d). In addition, four clones which had been exposed to the CRISPR/Cas9 machinery but were wild type (WT) at the FLCN locus were included as controls. As a phenotypic readout, we performed RNA-seq on all monoclonal lines.

Figure 5. Haplotype aware genome editing of a Mendelian disease SNP in FLCN demonstrates that expression regulatory variation can modify its penetrance.

a) Illustration of the experimental study design. Briefly, a SNP that causes Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome was edited on distinct eQTL haplotypes in 293T cells using CRISPR/Cas9. Monoclonal cell lines were genotyped and classified as monoallelic for the edit SNP (snpMONO), or as having a single copy. Using targeted RNA-seq, single copy clones were classified as either those where the edited SNP was on the lower (snpLOW) or higher (snpHIGH) expressed haplotype. The global transcriptome was used a cellular phenotype to assess SNP penetrance. b) Copy number normalized expression of the edited SNP as measured by targeted RNA-seq (allelic expression, log2(ALT/REF)) in snpLOW (allelic expression < 0, p-value < 0.01, binomial test versus 0.5) and snpHIGH (allelic expression > 0, p-value < 0.01) clones. Center lines represent median. c-d) Change in expression of genes that were significantly downregulated (c, 277 genes) or upregulated (d, 387 genes) in clones monoallelic for the edited SNP versus wild-type controls. Single copy edit SNP clones are stratified by haplotype configuration. P-values were calculated using a two-sided paired Wilcoxon signed rank test. See Supplementary Figure 7 and Supplementary Tables 4-6 for experimental details and additional analyses. For all plots, N = 4 snpLOW, 3 snpHIGH, 2 snpMONO, and 4 WT biologically independent samples. For boxplots, bottom whisker: Q1–1.5*IQR, top whisker: Q3+1.5*IQR, box: IQR, center: median, and outliers are not plotted for ease of viewing.

Using the transcriptomes of these clones, we carried out differential expression analysis. Introduction of the Mendelian SNP had a genome-wide effect on gene expression, with 664 of 20,507 tested genes being significantly (FDR < 10%) differentially expressed in clones monoallelic for the SNP versus wildtype controls (Supplementary Figure 7c, Supplementary Table 5). Gene set enrichment analysis 33 of differential expression test results revealed significant (FDR < 10%) enrichment of pathways related to cell cycle control, DNA replication, and metabolism, consistent with the annotation of FLCN as a tumor suppressor, and the occurrence of tumors in patients with the mutation (Supplementary Table 6). To study the joint effect of the eQTL and Mendelian variant, we quantified the differential expression of these 664 genes in low and high edited SNP expression clones separately (Fig. 5a). As we predicted, clones with higher expression of the SNP showed a significantly stronger differential expression of both downregulated (median = 8.10% increase; 95% CI = 5.93% to 10.36%; p = 8.60e-14) and upregulated (median = 6.52% increase; 95% CI = 4.76% to 8.22%; p = 4.40e-11) genes compared to lower SNP expression clones (Figs. 5c-d). Supporting this, 350 of the 664 genes affected by the Mendelian variant were significantly (FDR < 10%) differentially expressed in the high SNP expression clones, compared to only 186 in the low SNP expression clones. These results provide experimental demonstration that an eQTL can modify the penetrance of a disease-causing coding variant, and suggest a genetic regulatory modifier mechanism as a potential explanation of variable penetrance of rs199643834 in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. While further animal models or analyses of large patient cohorts would be needed to fully describe how the cellular transcriptome effects may translate to modified penetrance at a complex phenotype level, the use of genome editing in relevant cell lines and the transcriptome as a molecular phenotype will be an important and scalable approach for studying effects at individual genes of clinical importance.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have studied the hypothesis that regulatory variants in cis can affect the penetrance of pathogenic coding variants. We used diverse data types from population and disease cohorts, and experimental approaches that together provide strong evidence of modified penetrance due to joint functional effects of regulatory and coding variants. Our functional genomic and genetic analysis of the general population provides evidence that purifying selection is acting on joint regulatory and coding variants haplotypes. Importantly, this suggests that the combination of an individual’s regulatory and coding variant genotypes has an effect on phenotype, since purifying selection acts only on traits that affect fitness. Notably, we observed a weaker signal when analyzing eQTL haplotype configurations from genetic data alone as compared to ASE data. This difference could arise because the genetic analysis inferred expression haplotypes using the top common regulatory variant per gene as opposed to directly measuring them using expression data. Such an approach does not capture the combinatorial effects of independent common regulatory variants or the effects of rare regulatory variation, both of which might make significant contributions to modified penetrance.

Our case-control analyses of autism and cancer cohorts provide direct evidence that regulatory modifiers of coding variants contribute to disease risk, which is jointly driven by the combination of an individual’s eQTL and coding variant genotypes. Furthermore, our experimental approach provides indication of potential regulatory modifiers in the Mendelian Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. The approaches developed and introduced in this work can be applied to additional disease data sets, with GTEx data providing an essential resource of regulatory variants to empower these analyses. In individual genes, finding regulatory modifiers will require relatively large data sets, and studies of large families with segregating coding variants may be a particularly powerful approach. Genome editing experiments, as we demonstrated for FLCN, will be important for functionally validating results from computational analysis.

A key component of our work was the integrated analysis of rare coding variants and common regulatory variants, which are too often considered as separate domains in human genetics, despite the fact that their interplay is gaining increasing interest 34. Currently, rare coding variants are studied largely by exome sequencing in relatively rare diseases, and common regulatory variant analyses are focused on applications in genome-wide association studies of common diseases. Setting the stage for future studies, our work supports one of the few concrete and generalizable models of modified penetrance of genetic variants in humans, with a clear biological mechanism based on the net effect of variants on the dosage of functional gene product, and is backed by solid empirical analysis of genome-wide genetic data.

This work opens additional important areas for future research. Our results demonstrate that the strength of modified penetrance depends on the functional importance and dosage-sensitivity of the gene, effect size of the regulatory variants that affect expression or splicing, and the type of coding variant. Larger data sets are needed to uncover this full spectrum at the level of individual genes instead of gene classes analyzed here. In this work, we focused on loss-of-function analysis, where the expression level of the non-mutant haplotype matters, but it is likely that for less common gain-of-function germline and somatic variants, modified penetrance may depend on the expression of the mutant haplotype instead. This may be an important consideration for potential future work on variable penetrance of somatic variants in cancer. The dynamics of natural selection on haplotype combinations will be an interesting area of population genetic analysis, where an individual’s fitness depends on multiple variants on different homologs, as well as linkage disequilibrium between these variants.

Finally, we highlight that while other mechanisms are also likely to contribute to variable penetrance of coding variants, analysis of cis-regulatory modifiers is particularly tractable, with multiple practically feasible approaches introduced in this work. Our findings highlight the importance of considering coding variation in the context of regulatory haplotypes in future studies of modified penetrance of genetic variants affecting disease risk.

Online Methods

Variant Annotation

Variant annotations for SNPs were retrieved from CADD v1.3 15. As per guidelines by the CADD authors, missense variants with a CADD PHRED score of > 15 which is the median CADD score across all possible canonical splice site and missense variants were defined as potentially pathogenic. Synonymous variants with a CADD PHRED score < 15 were used as controls. To be considered rare, variants were required to have a MAF < 1% across GTEx v7, 1000 Genomes Phase 3 35, and gnomAD r2.0.1 22.

GTEx Allelic Expression Analysis

GTEx v6p allelic expression data generated from whole exome sequencing genotypes were used 14. Variants that were in low mappability regions (UCSC mappability track < 1), showed mapping bias in simulations 36, or had significant (FDR < 1%) evidence that the variant was monoallelic in that individual across all GTEx tissues were excluded to reduce mapping bias 16. Only variants with at least 10 reads were used. To minimize the probability that the observed allelic imbalance was due to effects of the AE variants themselves on splicing, only variants farther than 10 bp from an annotated splice site 15 were used. Within each GTEx tissue, when AE measurements from the same variant were present from different individuals, the measurement with the highest read coverage was used. Only variants where the alternative allele was the minor allele were used to ensure that mapping biases were consistent across variants. For missense variants, matched synonymous controls were selected controlling for allele frequency within 25% of missense variants (e.g. between 0.75% and 1.25% for a 1% frequency missense variant). Allelic fold change (aFC) was calculated as log2(alternative allele reads+1/reference allele reads+1)).

GTEx Exon Inclusion Quantification Analysis

Individual level quantifications of exon inclusion were generated for all GTEx v6p samples with the VAST-TOOLS pipeline, which measures the percent spliced in (PSI) of each exon in each individual 18. Within a given tissue, for each exon with at least 10 PSI measurements, PSI z-scores were generated for each sample. Individuals with substantial variation in exon inclusion compared to the population were defined as the top 10% of PSI z-scores across all sample exons (Supplementary Figure 2d).

GTEx Expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTL)

The official set of GTEx v6p top significant (FDR < 5%) eQTLs by permutation p-value were used for all analyses such that each gene by tissue had at most a single eQTL 14. Those eQTLs where the 95% confidence interval of eQTL effect size overlapped 0, representing weak eQTLs, were discarded 17. To produce a single set of cross-tissue top eQTLs, the top eQTL by FDR across tissues was selected for each eGene, with ties broken by choosing the eQTL with the larger effect size. This resulted in a set of 26,942 eGenes each with a single eSNP (Supplementary Table 1).

Genetic Data and Haplotype Phasing

GTEx – GTEx v7 genotypes from whole genome sequencing of the 620 individuals who had at least one RNA sample were used. These genomes were population and read-back phased using DNA-seq reads with SHAPEIT2 19. Following this, phASER v1.0.0 was used to perform read-backed phasing using RNA-seq reads 20 from all samples for each individual, which was a median of 17 tissues, and ranged from 1 to 38. For RNA-seq based read-backed phasing, only uniquely mapping reads (STAR MAPQ 255) with a base quality of ≥ 10 overlapping heterozygous sites were used, and all other phASER settings were left as default. The resulting phased genotypes were imputed into 1000 Genomes Phase 3 35 with Minimac3 v2.0.1 37.

SSC – Genotypes of the SSC cohort from Sanders et al. consisting of data generated on Illumina 1Mv1, 1Mv3, and Omni2.5 arrays 26 were transmission phased using SHAPEIT2 with relatedness data 38 and then imputed into the 1000 Genomes Phase 3 panel using the Sanger Imputation Service with PWBT 39,40. Coding variants called from WES data in Iossifov et al., were transmission phased on a per variant basis when possible using the genotypes of both parents. In total, genetic data from 2,304 ASD affected probands and 1,712 unaffected siblings was used for the analysis. Expression haplotypes of coding variants were annotated on the most significant eQTL variant for each gene in GTEx v6p across all tissues. The top GTEx eQTLs from across all tissues were used for analysis instead of brain regions only, due to the substantially lower sample sizes in GTEx brain tissues, which result in fewer eQTLs discovered.

TCGA – Paired tumor and normal WGS reads from 925 individuals across 15 cancer types were used to call germline and somatic variants with Bambino v1.06 41. The resulting germline genotypes were population phased with EAGLE2 v2.3 42 using the 1000 Genomes Phase 3 panel 35 and read-back phased with phASER v1.0.0 20. For read-backed phasing, only reads with MAPQ ≥ 30 and with a base quality of ≥ 10 overlapping heterozygous sites were used, and all other phASER settings were left as default. The resulting phased genotypes were imputed into 1000 Genomes Phase 3 35 with Minimac3 v2.0.1 37. Due to the highly variable sequencing depth across TCGA whole genome libraries, from the 925 individuals, 615 individuals with high quality genotyping and phasing were selected for downstream analysis by filtering the bottom 30% of samples by number of variants called and median EAGLE phase confidence across autosomes. This resulted in an approximately equal number of TCGA (615) and GTEx (620) individuals for analyses. Expression haplotypes of coding variants were annotated on the most significant eQTL variant for each gene in GTEx v6p across all tissues.

The TCGA individuals analyzed and GTEx v7 individuals used as a control had very similar inferred ancestry compositions, although the TCGA individuals had a slightly higher proportion of individuals with Asian ancestry (Supplementary Table 7). To ensure that the results are robust to ancestry proportions, we performed our analysis removing these individuals from the TCGA data set. We found that while the analysis was less powered, resulting in larger confidence intervals for the TCGA cohort, the results were consistent and significant (Supplementary Figure 6c).

Test for Regulatory Modifiers of Penetrance Using Phased Genetic Data

Here we test the hypothesis that in loss-of-function coding variant heterozygotes, decreased expression of the major, or “wild type” coding allele mediated by an eQTL can increase the penetrance of the mutant allele by decreasing the dosage of functional gene transcript, and vice-versa (Supplementary Figure 1). The null hypothesis is that eQTL mediated changes of major allele expression have no effect on the penetrance of mutant alleles. Since penetrance cannot be easily measured, we instead measure the frequency that the major allele is observed on the lower expressed eQTL haplotype (Supplementary Figure 3a). Under the null hypothesis, a coding mutation would occur in random individuals in the population, and on random haplotypes in those individuals, irrespective of their eQTL genotype. Thus, under the null, the frequency of observed major alleles on lower expressed haplotypes would simply be equal to the frequency of the lower expressed eQTL allele in the population. Alternatively, an increased frequency indicates an enrichment of haplotype configurations that increase coding variant penetrance in the population studied, and vice-versa (Supplementary Figure 3b). Importantly, the test is calibrated to the eQTL frequency in the specific population studied, so it is internally controlled for differences in, for example, eQTL allele frequencies between cases and controls.

To perform the test, for each observation of a heterozygous coding variant of interest the phased genotypes of the coding variant and the top GTEx cross-tissue eQTL for that gene are used to produce a binary measure of whether the major coding allele is on the lower expressed haplotype (Supplementary Figure 3a). Alongside this binary measure the frequency of the lower expressed eQTL allele is recorded.

For each observation of a heterozygous coding variant in a single individual, with genotype g let A and a denote the higher and lower expressed eQTL alleles, respectively, and B and b denote the major and minor coding variant alleles, respectively. We assume that the minor allele is the non-functional allele. For a given haplotype g, we define the indicator function β such that it is 1 if the functional allele is on a lower expressed eQTL haplotype, and 0 otherwise:

For a given haplotype the expectation for β under the null model, where the haplotype configurations are random (H0), is:

Where f(a) is the population frequency of the lower expressed eQTL allele included in the tested haplotype g.

The indicator function β and its expectation under the null model is calculated across all individuals, genes, and variants. The average relative deviation of observed mean of β from its expectation was calculated:

Where N is the total number of observed haplotype configurations consisting of an eQTL and coding variant, pooled over all individual, variants, and genes.

Confidence intervals for ε are generated by bootstrapping genotypes and the two-sided empirical p-value against H0 is calculated as:

Where B is the total number of bootstraps.

We ran the test on simulated haplotype data from 1000 individuals at 500 genes with 1000 replicates. The lower expressed haplotype frequency was set to 50% and the coding variant frequencies as observed in GTEx. This was done across a range of genes exhibiting a bias of major coding alleles being found on lower expressed haplotypes and strengths of this bias. For the test, 1000 bootstrap samples were used. We found that at 5% significance threshold, 5% of simulation replicates were significant, suggesting that the test is well calibrated under the null. For real world data, reported in the study, we used 100,000 bootstrap samples to calculate p-values and derive confidence intervals.

This is a similar problem to that addressed by the Poisson-Binomial distribution, which describes the sum of successes in a set of independent Bernoulli trials with different success rates. However, the bootstrap approach is more convenient for calculating confidence intervals and accounting for differences in sample size between control genes and genes of interest. We compared p-values derived from our test to those derived from a Poisson-Binomial distribution with parameters E[β(g1)]…E[β(gN)]. In practice, our p-values are very similar to that generated using the Poisson-Binomial distribution (Pearson correlation = 0.996, slope = 0.997, Supplementary Figure 3e).

A key part of our test is that as opposed to simple linkage disequilibrium it tests a specific directional hypothesis: the frequency that coding variant functional alleles are on lower expressed regulatory haplotypes. Thus, in the absence of selection on regulatory haplotype configurations, differences in recombination rates between genes would not be expected to bias the results of our test. However, it is possible that the distribution of distances between the coding and regulatory variants tested could differ between test sets. In order to ensure that this is not the case, we compared the distance between coding and eQTL variants for each of the relevant tests performed and saw no significant difference in distance distribution for any of the relevant test pairs (Supplementary Figure 8).

Gene Sets

Genes with strong eQTLs were selected as the top 25% of eGenes by absolute eQTL effect size 17. A conservation score was calculated for each eGene as the median UCSC hg19 placental mammal base conservation across all exons. Loss-of-function and missense intolerant genes were selected by requiring ExAC pLI ≥ 0.9 and significant missense constraint (FDR < 10%) 22. P-values for missense constraint were generated from ExAC missense z scores using the R command ‘p=2*pnorm(-abs(mis_z))’ and Benjamini-Hochberg corrected to control for FDR. A broad set of genes associated with autism spectrum disorder was produced by combining high confidence SFARI database genes (see URLs, categories 1, 2, and S) downloaded on 10/20/17, genes from Krumm et al., with nominally significant (p < 0.05) enrichment of de novo SNVs in probands versus siblings, and genes with recurrent likely gene disrupting and missense de novo mutations in probands but not unaffected siblings in Iossifov et al. 27,28. These were further filtered by removing genes that are highly tolerant to genetic variation, as defined by being in the top 10% of tolerant genes by RVIS score (v3_12Mar16) 43. In total, this resulted in a list of 455 ASD associated genes. A list of 983 down-regulated tumor suppressor genes in tumor samples versus normal tissue in TCGA expression data was downloaded from the Tumor Suppressor Gene Database 44 website (see URLs) on 08/24/17.

CRISPR/Cas9 Guide Selection and Cloning

Prior to RNA design and editing we verified the genotype at the regions of interest, namely the Mendelian variant rs199643834 and eQTL variant rs1708629. Crude extracts prepared from 293T cells were used to amplify the above regions using forward and reverse genotyping primers FLCN_genot and FLCNeQTL_genot, respectively (Supplementary Table 8). Amplicons were sequenced by both Sanger sequencing and on the Illumina MiSeq. The 293T cell genotype was Ref/Ref/Ref at rs199643834 and Ref/Ref/Alt at rs1708629. There were no single nucleotide changes close to rs199643834 that may affect sgRNA activity or require modified homologous template.

Using computational algorithms with prioritization for on-target efficiency and reduced off-target effects from CRISPR Design tool (see URLs) and E-CRISPR 45 we identified Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) guide RNAs that bind near variant rs199643834 (A > G). We selected three sgRNA sequences within 50 bp of the target SNP (rs199643834), which were predicted to result in maximum cleavage efficiency without off-target effects (Supplementary Table 8). Annealed oligomers inclusive of guide RNA sequences were sub-cloned into the lentiCRISPRv2 plasmid (Addgene plasmid #52961), which contains expression cassettes for the guide RNA, a human codon-optimized Cas9, and a puromycin resistance gene 46. Plasmids were transformed into chemically competent E. coli (One Shot Stbl3 Chemically Competent E. coli, ThermoFisher Scientific, cat#: C737303), and grown at 30°C; plasmid DNA was extracted and purified. A 150 bp single-stranded DNA template (ssODN) for precise editing by homologous recombination (HDR) carrying the rs199643834 A allele was designed and obtained from IDT DNA in the form of lyophilized ultramer (Supplementary Table 8).

Transfections and T7 Endonuclease I(T7E1) Assays

Human 293T cell line (ATCC, cat. # CRL-3216) was adapted to and subsequently routinely grown in Opti-MEM/5% CCS (newborn calf serum), 1% GlutaMAX, 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin and sodium pyruvate. For transfection with Cas9- and sgRNA-expressing plasmids as well as ssODN template, cells were harvested for seeding at a log growth phase (approximately 70% confluency). In a 6-well format, 300,000 293T cells were seeded a day prior to transfection. The next day 2 μg of each lentiCRISPR v2 plasmid and 0.5 μg of ssODN HDR template were delivered into the cells using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, cat. # L3000008). At 24-hours post-transfection selective pressure in the form of 5 μg/ml puromycin was applied for 8 hours to enrich for transfected cells. The short time- frame reduces the chances of selecting monoclonal lines with stable plasmid integration. Following two days of cell growth cells were harvested and crude extracts prepared from a small fraction for genotyping. The remainder of the cells were frozen for subsequent isolation of cell lines containing desired edits.

For T7E1 assays, a 362 base pair region flanking rs199643834 was PCR-amplified from the crude extracts using FLCN_genot primers and purified using Ampure XP beads (Beckman-Coulter, part #: A63880). Purified products were heteroduplexed, digested with T7 endonuclease 1 (NEB, cat # M0302L), and run on a 2% agarose gel. Cleavage patterns from editing experiments conducted with each sgRNA were qualitatively analyzed to determine each Cas9/sgRNA cutting efficiency to guide further experiments. Subsequently, the crude cell lysates were used to prepare amplicon libraries containing ScriptSeq adapters, which were sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq instrument with paired-end 150 bp reads. Rates of indel mutations by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and precise SNP editing by homology-directed repair (HDR) were determined by an in-house analysis pipeline.

Generation and Identification of Monoclonal Cell Lines Containing Desired Precise Edits

The initial screening showed that editing of 293T polyclonal cell population at rs199643834 with sgRNA 1 resulted in the highest rate of HDR. This population was selected for single-cell sorting in 96-well format on SONY SH800 to obtain monoclonal edited cell lines. Following 10 days of cell growth, individual wells were scored for the presence of healthy colonies, and altogether approximately 1920 healthy colonies were screened. At first passage a third of the cells from each well were collected for crude cell extracts and genotyping.

High throughput genotyping was performed by preparing an amplicon library from each crude extract with Nextera adapters enabling differential custom dual-indexing. Screening for desired mutations was performed using in-house software. In total, 4 wild-type (Ref/Ref/Ref), 7 heterozygous (Ref/Ref/Alt) and 2 homozygous mutant (Alt/Alt/Alt) clones with each desired mutation were expanded for downstream analyses.

Targeted RNA-seq of Allelic Series and eQTL Phasing

Expanded lines were grown to 70–80% confluency and RNA was isolated using the Qiagen RNAeasyMini kit. cDNA was synthesized from each RNA sample and the region spanning the Mendelian variant rs199643834 was amplified using primers FLCN_exon9–10-F and FLCN_exon11-R2, containing Nextera adapters (Supplementary Table 8). Targeted amplicons were dual-indexed using custom Nextera indexes and sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq with 2×150 bp reads.

For all the 13 lines the genotype determined by DNA-sequencing was confirmed by RNA-seq reads. For the 7 lines with a single copy of the edited SNP, we performed allelic expression analysis. Reads were aligned to hg19 using STAR 47. The number of reads mapping to the reference and alternative alleles was quantified using allelecounter requiring MAPQ = 255 and BASEQ ≥ 10 16. Across samples, there was a median of 34,870 reads passing filters overlapping the site. A binomial test using reads containing the edit SNP allele against a null of 1/3 (corresponding to a single copy of the edit SNP) was performed. Copy number normalized allelic expression of the edit SNP was calculated as log2((ALT_COUNT/REF_COUNT)/(1/3)). Samples with allelic expression < 0 and binomial p < 0.01 were categorized as snpLOW (edit SNP on lower expressed eQTL haplotype), and those with allelic expression > 0 and binomial p < 0.01 were categorized as snpHIGH (edit SNP on higher expressed eQTL haplotype).

RNA-seq and Gene Expression Analysis of Edited 293T Cells

RNA sequencing libraries were prepared using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Sample Preparation Kit in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 500ng of total RNA was used for purification and fragmentation of mRNA. Purified mRNA underwent first and second strand cDNA synthesis. cDNA was then adenylated, ligated to Illumina sequencing adapters, and amplified by PCR (using 10 cycles). Final libraries were evaluated using fluorescent-based assays including PicoGreen (Life Technologies) and Fragment Analyzer (Advanced Analytics), and were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq Sequencing System using 2 × 100bp cycles to a median depth of 52.8 million reads. Trimmomatic 48 v0.36 was used to clip Illumina adaptors and quality trim, and reads were aligned to hg19 using STAR 47 in 2 pass mode. A median of 98% of reads mapped to the human genome, with a median of 95.2% reads mapping uniquely. featureCounts 49 v1.5.3 was used in read counting and strand specific mode (-s 2) with primary alignments only to generate gene level read counts with Gencode v19 annotations used in GTEx v6p 14. Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 50 v1.16.1 and R v3.4.0 on genes with a mean of greater than 5 counts across samples. FDR correction of p-values was performed using Benjamini Hochberg. Gene set enrichment analysis on differential expression data was performed using the Web-based Gene Set Analysis Toolkit 33 with Wikipathway enrichment categories.

Data Availability Statement

GTEx v6p eQTLs are publicly available through the GTEx Portal (see URLs). GTEx genotype data, AE data, and RNA-seq reads are available to authorized users through dbGaP (study accession phs000424.v6.p1, phs000424.v7.p2). TCGA data is available to authorized users through dbGap (study accession phs000178.v9.p8). 293T RNA-seq data generated in this study is available through GEO under accession GSE116061.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank members of the Lappalainen lab for discussion surrounding the project, and both Kristin Ardlie and Sampsa Hautaniemi who supervised F.A. and A.C. respectively. We thank the GTEx donors for their contributions to science, the GTEx Laboratory, Data Analysis, and Coordinating Center (LDACC), and the GTEx analysis working group (AWG) for their work generating the resource. In particular we would like to thank Ayellet Segre and Xiao Li at the Broad for their work performing WGS variant calling and phasing of GTEx v7 data. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project was supported by the Common Fund of the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health, and by NCI, NHGRI, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, and NINDS. We would also like to acknowledge the families at the participating Simons Simplex Collection (SSC) sites, the principal investigators at each site, the coordinators and staff at the SSC sites, the SFARI staff, and the UMACC. Funds for the SSC were provided by the Simons Foundation. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge the contribution of TCGA specimen donors, and The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network for their analyses. Funds for the TCGA were provided by Cancer Institute and the National Human Genome Research Institute. S.E.C. was supported by the NHGRI grant 1K99HG009916–01, T.L. and S.E.C. were supported by the NIGMS grant R01GM122924 and NIMH grant R01MH101814, T.L., S.E.C., and P.M. were supported by the NIH contract HHSN2682010000029C, T.L. and P.M. were supported by NIMH grant R01MH106842, and T.L. was supported by the NIH grant UM1HG008901 and 1U24DK112331. A.C. was supported by the Cancer Society of Finland and Academy of Finland grant 284598.

Footnotes

URLs

SFARI gene database - https://gene.sfari.org

Tumor Suppressor Gene Database - https://bioinfo.uth.edu/TSGene/

GTEx Portal - https://gtexportal.org/

CRISPR Design Tool – http://crispr.mit.edu

Competing Financial Interests Statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Chen R et al. Analysis of 589,306 genomes identifies individuals resilient to severe Mendelian childhood diseases. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 531–538 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper DN, Krawczak M, Polychronakos C, Tyler-Smith C & Kehrer-Sawatzki H Where genotype is not predictive of phenotype: towards an understanding of the molecular basis of reduced penetrance in human inherited disease. Hum. Genet. 132, 1077–1130 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milne RL & Antoniou AC Genetic modifiers of cancer risk for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Ann. Oncol. 22 Suppl 1, i11–7 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emison ES et al. A common sex-dependent mutation in a RET enhancer underlies Hirschsprung disease risk. Nature 434, 857–863 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei W-H, Hemani G & Haley CS Detecting epistasis in human complex traits. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 722–733 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snozek CLH et al. LDLR promoter variant and exon 14 mutation on the same chromosome are associated with an unusually severe FH phenotype and treatment resistance. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 17, 85–90 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alberobello AT et al. An intronic SNP in the thyroid hormone receptor β gene is associated with pituitary cell-specific over-expression of a mutant thyroid hormone receptor β2 (R338W) in the index case of pituitary-selective resistance to thyroid hormone. Journal of Translational Medicine 2011 9:1 9, 144 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butt C et al. Combined carrier status of prothrombin 20210A and factor XIII-A Leu34 alleles as a strong risk factor for myocardial infarction: evidence of a gene-gene interaction. Blood 101, 3037–3041 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amin AS et al. Variants in the 3’ untranslated region of the KCNQ1-encoded Kv7.1 potassium channel modify disease severity in patients with type 1 long QT syndrome in an allele-specific manner. Eur. Heart J. 33, 714–723 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimas AS et al. Modifier Effects between Regulatory and Protein-Coding Variation. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000244–10 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lappalainen T, Montgomery SB, Nica AC & Dermitzakis ET Epistatic selection between coding and regulatory variation in human evolution and disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 89, 459–463 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vu V et al. Natural Variation in Gene Expression Modulates the Severity of Mutant Phenotypes. Cell 162, 391–402 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.GTEx Consortium. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat. Genet. 45, 580–585 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.GTEx Consortium. Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature 550, 204–213 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kircher M et al. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat. Genet. 46, 310–315 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castel SE, Levy-Moonshine A, Mohammadi P, Banks E & Lappalainen T Tools and best practices for data processing in allelic expression analysis. Genome Biol. 16, 195 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohammadi P, Castel SE, Brown AA & Lappalainen T Quantifying the regulatory effect size of cis-acting genetic variation using allelic fold change. Genome Res. 1–14 (2017). 10.1101/gr.216747.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Irimia M et al. A highly conserved program of neuronal microexons is misregulated in autistic brains. Cell 159, 1511–1523 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delaneau O, Howie B, Cox AJ, Zagury J-F & Marchini J Haplotype estimation using sequencing reads. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 93, 687–696 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castel SE, Mohammadi P, Chung WK, Shen Y & Lappalainen T Rare variant phasing and haplotypic expression from RNA sequencing with phASER. Nat Commun 7, 12817 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samocha KE et al. A framework for the interpretation of de novo mutation in human disease. Nat. Genet. 46, 944–950 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lek M et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 536, 285–291 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network et al. The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer analysis project. Nat. Genet. 45, 1113–1120 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Payne SR & Kemp CJ Tumor suppressor genetics. Carcinogenesis 26, 2031–2045 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischbach GD & Lord C The Simons Simplex Collection: a resource for identification of autism genetic risk factors. Neuron 68, 192–195 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanders SJ et al. Insights into Autism Spectrum Disorder Genomic Architecture and Biology from 71 Risk Loci. Neuron 87, 1215–1233 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iossifov I et al. The contribution of de novo coding mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Nature 515, 216–221 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krumm N et al. Excess of rare, inherited truncating mutations in autism. Nat. Genet. 47, 582–588 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toro JR, Wei M-H, Glenn GM & Weinreich M BHD mutations, clinical and molecular genetic investigations of Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome: a new series of 50 families and a review of published reports. J Med Genet 45, 321–331 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khoo SK et al. Clinical and genetic studies of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 39, 906–912 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin Y-C et al. Genome dynamics of the human embryonic kidney 293 lineage in response to cell biology manipulations. Nat Commun 5, 4767 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ward LD & Kellis M HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucl Acids Res 40, D930–4 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J, Vasaikar S, Shi Z, Greer M & Zhang B WebGestalt 2017: a more comprehensive, powerful, flexible and interactive gene set enrichment analysis toolkit. Nucl Acids Res 45, W130–W137 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Werling DM et al. Limited contribution of rare, noncoding variation to autism spectrum disorder from sequencing of 2,076 genomes in quartet families. bioRxiv 127043 (2017). 10.1101/127043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Methods-only References

- 35.1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68–74 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Panousis NI, Gutierrez-Arcelus M, Dermitzakis ET & Lappalainen T Allelic mapping bias in RNA-sequencing is not a major confounder in eQTL studies. Genome Biol. 15, 467 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Das S et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat. Genet. 48, 1284–1287 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Connell J et al. A general approach for haplotype phasing across the full spectrum of relatedness. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004234 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCarthy S et al. A reference panel of 64,976 haplotypes for genotype imputation. Nat. Genet. 48, 1279–1283 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Durbin R Efficient haplotype matching and storage using the positional Burrows-Wheeler transform (PBWT). Bioinformatics 30, 1266–1272 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edmonson MN et al. Bambino: a variant detector and alignment viewer for next-generation sequencing data in the SAM/BAM format. Bioinformatics 27, 865–866 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loh P-R et al. Reference-based phasing using the Haplotype Reference Consortium panel. Nat. Genet. 48, 1–8 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petrovski S, Wang Q, Heinzen EL, Allen AS & Goldstein DB Genic intolerance to functional variation and the interpretation of personal genomes. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003709 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao M, Kim P, Mitra R, Zhao J & Zhao Z TSGene 2.0: an updated literature-based knowledgebase for tumor suppressor genes. Nucl Acids Res 44, D1023–D1031 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heigwer F, Kerr G & Boutros M E-CRISP: fast CRISPR target site identification. Nat. Methods 11, 122–123 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanjana NE, Shalem O & Zhang F Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat. Methods 11, 783–784 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dobin A et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bolger AM, Lohse M & Usadel B Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liao Y, Smyth GK & Shi W featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Love MI, Huber W & Anders S Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

GTEx v6p eQTLs are publicly available through the GTEx Portal (see URLs). GTEx genotype data, AE data, and RNA-seq reads are available to authorized users through dbGaP (study accession phs000424.v6.p1, phs000424.v7.p2). TCGA data is available to authorized users through dbGap (study accession phs000178.v9.p8). 293T RNA-seq data generated in this study is available through GEO under accession GSE116061.