Abstract

The plasticity of plant morphology has evolved to maximize reproductive fitness in response to prevailing environmental conditions. Leaf architecture elaborates to maximize light harvesting, while the transition to flowering can either be accelerated or delayed to improve an individual’s fitness. One of the most important environmental signals is light, with plants using light for both photosynthesis and as an environmental signal. Plants perceive different wavelengths of light using distinct photoreceptors. Recent advances in LED technology now enable light quality to be manipulated at a commercial scale, and as such opportunities now exist to take advantage of plants’ developmental plasticity to enhance crop yield and quality through precise manipulation of a crops’ lighting regime. This review will discuss how plants perceive and respond to light, and consider how these specific signaling pathways can be manipulated to improve crop yield and quality.

Tailoring the perfect crop with light

Crop yields and qualities can be improved by manipulating their photoreceptors with light. Matthew Jones of the UK’s University of Essex reviewed the latest research on plant responses to various wavelengths of light and how photoreceptor pathways can be manipulated to improve commercial crops. Plants contain a variety of photoreceptors, each responding to distinct wavelengths of light to initiate cellular pathways that affect plant growth and development. These pathways can lead to the formation of pigments that improve fruit quality. They also play roles in plant responses to shade, daily and seasonal changes in light, and flowering times. Recent developments in cost-effective LED lights can lead to the optimization of crop growth. However, further research is needed to understand the differences in photoreceptors and their pathways in various plants.

Introduction

The effective application of light is essential for plant husbandry, but the demands of modern, intensive horticulture often conflict with the optimal planting strategy for plant growth. Dense planting regimes induce shading throughout the canopy, with individual plants striving to optimize light harvesting at the expense of their neighbors. This intra-crop competition leads to a varied light environment that has consequences for crop uniformity and total yield, which is exacerbated by changing light availability over the course of the year1. Historically, horticulturalists have sought to mitigate these effects through the development of varieties with altered developmental responses that improve harvest. Alternatively, enclosed glasshouses enable control of light, temperature, humidity, and CO2, each of which can alter plant development. The recent advent of commercially-viable LED-based lighting provides an additional opportunity to optimize plant development through the application of specific light wavelengths at times most appropriate to optimize crop traits. These manipulations will be of immediate benefit for glasshouse-grown plants where supplemental light can be readily provided, although as LED technology advances there will be opportunities to apply similar approaches in the field. This review will summarize our understanding of plant perception and photomorphology and how this can be applied to optimize plant growth.

Plant photoreceptors

As photosynthetic organisms, plants need to harvest sufficient light energy to sustain growth and reproduce. However, it is not sufficient to simply irradiate plants with a single quality of light. Although monochromatic red or blue light sources (as chlorophyll predominantly absorbs light in the red and blue portions of the spectrum) can be used to cultivate crops, such plants develop atypically. This is likely because of the imbalanced activation of different photoreceptors which ultimately impairs photosynthesis either through inappropriate stomatal behavior or incorrect accumulation of photosynthetic pigments2,3. Plants sense light both through specific photoreceptors as well as by monitoring the metabolic consequences of photosynthesis4,5, thereby allowing light to be used as a predictive environmental indicator as well as an energy source. Shortening days imply the onset of winter and subsequent reductions in temperature whilst the spectrum of light provided by the sun is enriched in the blue portion of the spectrum at dawn and dusk relative to midday6. Given these environmental characteristics, plants have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to determine light availability and quality. Decades of research have revealed a complex network of photosensory pathways that enable plants to precisely respond to light quantity, quality, and duration5,6. Perhaps more importantly, plants are able to respond and adapt to each of these stimuli. In an evolutionary context, plants responses to light have been selected to maximise their survival; the challenge facing horticulturalists is how these existing light-responsive traits can be modified or selectively activated to increase yield and crop quality.

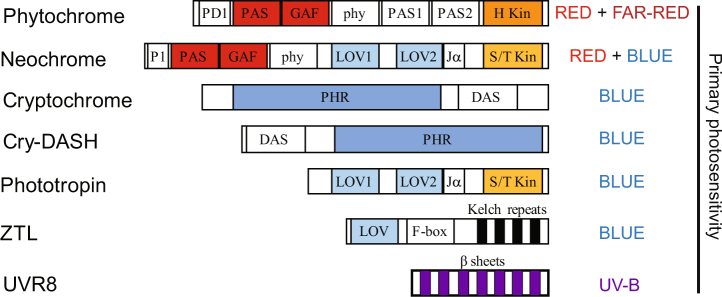

In contrast to animals, which have evolved specialized light sensing organs, plants perceive light in a cell-autonomous fashion. Plants have evolved a suite of photoreceptors (Fig. 1), each of which provide sensitivity to different portions of the light spectrum by binding a light absorbing co-factor (referred to as a chromophore7). Red and far-red light (600–750 nm) is primarily detected by the phytochrome family8 while blue and UV-A light (320–500 nm) is sensed by cryptochromes, phototropins, and members of ZEITLUPE/ADAGIO family7,9–11. UV-B light (290–320 nm) is perceived by the UVR8 photoreceptor12. In addition to these characterised photosensors, plants are also able to respond to ‘green’ light (500–600 nm), although the photoreceptors responsible for these responses have not been elucidated13. The existence of distinct photoreceptor families provides opportunities to selectively activate individual pathways, thereby precisely controlling plant development.

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram illustrating major domain structure of plant photoreceptors.

Domains necessary for red light detection are shown in red, whilst those for blue light detection are shown in blue. The N-terminal phytochrome PAS and GAF domains interlink to allow binding of a phytochromobilin chromophore whilst the cryptochrome PHR domain associates with FAD and MTHF chromophores. LOV domains bind a FMN chromophore. Kinase domains are highlighted in orange. DAS Drosophila, Arabidopsis, Synechocystis cryptochrome domain, FAD Flavin Adenosine Dinulceotide, FMN Flavin Mono-Nucleotide, GAF cGMP specific and -regulated cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase, Adenylyl cyclase, and FhlA, H Kin Histidine kinase, Jα Jα-helix, LOV Light/Oxygen/Voltage sensitive, MTHF Methenyltetrahydrofolate, PAS Per/Arnt/Sim, PD1 Phytochrome Domain 1, PHR Photolyase Homology Region, phy-Phytochrome domain 4, S/T Kin Serine/Threonine kinase

Phytochromes

Phytochromes were initially identified in 1959 as the photoreceptor that mediates plant photomorphogenesis in response to long-wavelength visible light14. The phytochrome family has since been found to be ubiquitous amongst seed plants and cryptophytes, with examples also being found in cyanobacteria, non-photosynthetic bacteria, and fungi15. Phytochromes (phy) are sensitive to irradiation by both red and far-red light, and uniquely function by measuring the relative quantity of each of these wavelengths15. The phytochrome basal state (designated Pr) is sensitive to red light and upon irradiation is converted to a far-red sensitive state (Pfr). Reversion to the Pr form occurs either after far-red light exposure or as a consequence of dark incubation. The relative amounts of each of these forms determine downstream signalling events, with the Pfr form considered to be the active signalling state16.

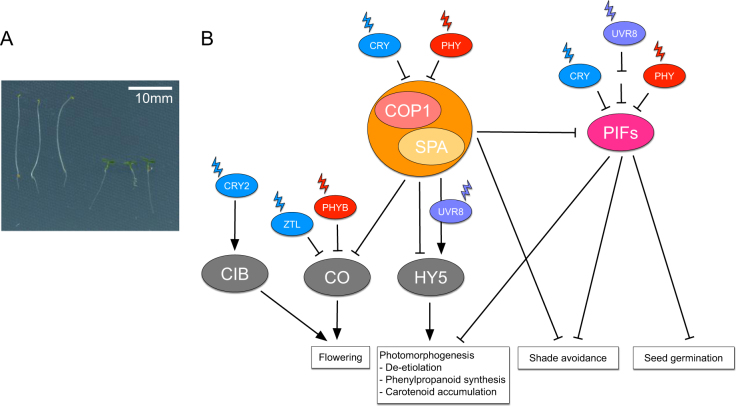

Higher plant genomes encode a suite of phytochrome proteins, each with slightly diverged light-sensitivity and function. Angiosperm phytochromes can be placed into two broad groups based upon the stability of the red light irradiated Pfr form. Type I phytochromes (such as phyA) accumulate in the dark and are rapidly degraded after illumination17. Type I phytochromes are primarily involved in very low light responses (VLFR) or those involving a high irradiance response (HIR), two signalling modes that are functionally different and appear to operate through at least partially distinct pathways18. Type II phytochromes (such as phyB-E) remain stable in the presence of light allowing these phytochromes to respond persistently to fluctuations in illumination (low fluence response, LFR19,20. LFR responses (such as shade avoidance) are reversible and are determined by the ratio of red and far red light used to irradiate the plant21. VLFR, HIR, and LFR interact to facilitate light sensitivity under a broad range of light conditions. As phyA is light-labile, phyA is generally considered to be the primary photoreceptor in etiolated seedlings, with phyB and other type II phytochromes having greater importance in light-grown plants with regards shade avoidance and the regulation of flowering time (Fig. 221).

Fig. 2. Photomorphogenesis is regulated by conserved signalling hubs.

a In the absence of light, seedlings have an etiolated phenotype (left). Upon perceiving light, plants initiate photomorphogensis leading to dramatic changes in plant architecture including cotyledon expansion and the inhibition of hypocotyl elongation (right). b Cryptochromes, phytochromes, and UVR8 perceive blue, red, and UV-B light respectively (see the section 'Plant photoreceptors'). Phytochromes and cryptochromes inhibit the activity of both the COP1/SPA and PIF signalling hubs, leading to changes in gene expression that culminate in photomorphogenesis and shade avoidance responses. Activated UVR8 modulates the function of the COP1/SPA complex to promote photomorphogenesis. The COP1/SPA complex has additional roles in the regulation of flowering, while PIFs influence seed germination. Cryptochromes and phytochromes also influence plant development independently of these signalling hubs; for instance CRY2 (see the section 'Cryptochromes') accelerates flowering via CIB transcription factors whereas phyB (see the section 'Phytochromes') inhibits CO accumulation in the morning independently of COP1 (see the section 'Shade avoidance'). CIB CRYPTOCHROME INTERACTING BASIC HELIX LOOP HELIX, CO CONSTANS, COP1 CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1, CRY Cryptochrome, HY5 ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL5, PHY Phytochrome, PIF PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR, UVR8 UV-B RESISTANCE LOCUS8, ZTL ZEITLUPE

Cryptochromes

Plant cryptochromes are blue light photoreceptors that are one of five subfamilies identified in the photolyase/cryptochrome family based on molecular phylogenetic analyses and functional similarity22. Cryptochromes have been identified in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, the closely related Brassica napus, and in a number of other model plant systems including pea, rice, and tomato10. The majority of plant genomes studied encode for two canonical plant cryptochrome proteins (CRY1 and CRY2) and one member of the CRY-DASH subfamily, which has been designated CRY3 (Fig. 123–26).

Cryptochromes perceive blue light via a flavin adenine dinucleotide chromophore, with blue light irradiation triggering conformational changes that culminate in cryptochrome dimerization and the activation of biochemical signalling pathways9,27. While CRY1 is stable when illuminated, CRY2 is degraded after light activation25,28,29. Cryptochromes largely induce changes in plant development through changes in gene expression30,31. These changes in gene expression induce physiological changes from de-etiolation through to flowering, and also have a role in the production of anthocyanins (Fig. 232). Cryptochromes have been found associated with DNA, but also activate CRYPTOCHROME INTERACTING BASIC HELIX LOOP HELIX (CIB) transcription factors and the CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 (COP1) and PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR (PIF) signalling hubs (Fig. 233,34).

Phototropins

Phototropins are plasma membrane-localised protein kinases which were initially characterised in Pisum sativum membrane extracts due to their blue-light-dependent phosphorylation35, Fig. 1). As in other photoreceptors, blue light induces conformational changes that generate a biologically-active state which gradually reverts to the dark-adapted form in the absence of light9. Since the identification of the PHOT1 locus in Arabidopsis36, phototropins have been characterised in numerous other dicots and monocots, as well as in lower plants such as the fern Adiantum capillis-veneris37. Studies have identified two primary members of the phototropin family, phototropin (phot) 1 and 236,38,39, both of which are found in Arabidopsis. The phots have partially redundant roles in many responses in Arabidopsis, but have some diverged functions; in general phot1 is sensitive to lower fluences of light while phot2 acts in response to higher light intensities40. Like phytochromes and cryptochromes, phots are capable of eliciting changes in gene expression in response to blue light stimulation, although compared to the modulation of gene expression induced by cryptochrome activity this role is minor41. Instead, phots are thought to act primarily at a post-transcriptional level to mediate responses to blue light. Phototropins have been shown to be the primary light receptors for a range of blue light-specific responses including phototropism (after which they were named), chloroplast accumulation, leaf positioning and expansion and also stomatal opening42. In addition, phot2 induces chloroplast avoidance movements under high light irradiation42.

Phot1 and phot2 appear to have evolved from a single gene duplication event after the evolution of seed plants36,39,43. Single copies of PHOT are found in pteridophytes and in the single-celled algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii44,45 and are likely derived from the ancestral PHOT gene43. In addition to these sequences, a chimeric photoreceptor (neochrome 1, neo1) has been identified in Adiantum and the alga Mougeotia scalaris which contains the red light-sensing N-terminal region of a phytochrome fused with a complete phototropin protein46. This fusion event allows both red and blue light to be used to induce what are primarily thought to be blue light-mediated phot-dependent responses in higher plants. This is thought to be advantageous in the shaded, low light environments in which these plants are commonly found47. Indeed, neochrome is thought to have arisen on two independent occasions in cryptophytes46.

ZEITLUPE family

The ZEITLUPE (ZTL) family consists of three members; ZEITLUPE (ZTL), FLAVIN BINDING, KELCH REPEAT, F-BOX1 (FKF1) and LOV KELCH PROTEIN2 (LKP2)48–50. Each of these proteins have a conserved structure consisting of an N-terminal LOV domain, an F-box domain which allows binding to a SKP1–CUL1–FBP (SCF) ubiquitin ligase, and a region of kelch repeats which are also thought to allow protein–protein interactions51. The existence of a light sensitive LOV domain coupled with an F-box suggested that these proteins may be involved in the light-dependent regulation of protein stability. Indeed, recent work has shown a role for ZTL and FKF1 in the circadian system where their light-dependent function allows modulation of internal timing signals52–54. This mechanism allows plants to induce flowering at favorable times of year by responding to seasonal changes in day length through light-dependent modulation of circadian clock signals52,55 (see the section 'Photoreceptors contribute to temperature sensitivity and endogenous timing signals').

UVR8

Although not detected by the human eye, sunlight contains a small proportion (<0.5%) of UV-A (315–400 nm) and UV-B (280–315 nm) light56. Plants perceive light via the UV-B RESISTANCE8 (UVR8) photoreceptor57,58, with loss of this photoreceptor leading to enhanced susceptibility to UV-B radiation59. UVR8 disassociates from its homodimer in the presence of UV-B light, with the resultant monomers binding with partners such as COP1 to induce changes in gene expression60–63. Although damaging in large quantities, UV-B induced signalling via the UVR8 pathway also has important benefits, promoting pest resistance, increasing flavonoid accumulation in fruits, improving photosynthetic efficiency, and serving as an indicator of direct sunlight and sunflecks56,64–68.

Photoreceptors contribute to temperature sensitivity and endogenous timing signals

Activated photoreceptors contribute to temperature perception

Although light serves a vital role in plant development it is important to consider how photoperception is integrated with other environmental information such as ambient temperature and time of day. Although a thorough discussion of plants responses to temperature are outside the scope of this review (see69,70 for recent overviews) it is becoming apparent that photoreceptors directly contribute to temperature perception. Recent work reveals that the stability of the light-activated states of phytochromes and phototropins is prolonged at lower temperatures through retardation of dark reversion71–73. This modulation of light signalling pathways by temperature allows immediate integration of these important environmental signals. This is particularly important in the context of LED lighting systems where the utilization of monochromatic light sources may have unintended consequences for plants perception of temperature through the specific activation of individual families of photoreceptors.

Plants responses to light are informed by the circadian system

While we have characterized many of the photoreceptors utilized by plants (see the section 'Plant photoreceptors') it is also apparent that biological timing mechanisms have arisen that regulate plants’ responses to these signals4,74. The circadian system is an internal timekeeping mechanism that consists of interlocking transcription/translation loops that generate an approximate 24-h cycle75. Approximately one third of the expressed transcriptome is regulated by the circadian system, with transcription of phytochromes, cryptochromes, phototropins, and UVR8 each being regulated by the circadian system76–78. In addition, the clock modulates photosensory pathways such that plants perception of light also varies during the day, a concept known as circadian gating74,79. The biological clock allows plants to anticipate daily environmental changes as well as acting as a reference to measure seasonal changes in day length75,80, consequently contributing to flowering time in photoperiod-sensitive species (see the section 'Photoperiodic control of flowering time').

Conversely, the circadian system is highly responsive to light, a quality necessary to ensure accurate perception of changing day lengths during the year. The loss of cryptochromes, or the removal of individual or multiple phytochromes, alters the progression of the circadian cycle under constant blue or red light respectively81–83. The ZTL family of blue light photoreceptors, named after the predominant member ZEITLUPE (ZTL), have similarly been shown to have a role in regulating the circadian system, with the other two ZTL family members, LKP2 and FKF1, providing partial redundancy for ZTL function84,85. The temporal regulation initiated by the clock, and its sensitivity to light, provide additional opportunities to precisely control crop development in response to light and should be considered when designing optimal lighting regimes for crops.

Plant development is controlled by light

Light is perhaps the most important consideration for optimizing plant growth, with light being utilized as both an energy source and as a developmental signal. All aspects of plant development are responsive to light, from germination through to the transition to flowering and fruit ripening86. The process by which developmental alterations occur in response to the changing light environment is referred to as photomorphogenesis6. In the absence of light newly-germinated seedlings have an etiolated phenotype with an extended hypocotyl (primary stem), an apical hook, and unopened cotyledons (embryonic leaves, Fig. 2a)86. These traits enable the seedling to rapidly emerge from the soil into the light at which point de-etiolation occurs, with dramatic consequences for seedling morphology. Light induces cotyledon expansion and the development of chloroplasts, thereby enabling photosynthesis, while hypocotyl elongation is curtailed. While this is perhaps the most dramatic light-induced developmental transition, light continues to be monitored throughout vegetative growth. Light intensity, duration, and spectral quality influence a range of vegetative characteristics including branching, internode elongation, leaf expansion, and orientation, with each of the photoreceptor families contributing via the photosensory network6,87. Light is also a fundamental signal necessary for the transition to flowering6, while the effects of light upon fruit development are also beginning to emerge.

Following photoperception phytochromes, cryptochromes, and UVR8, induce photomorphogenesis by inducing comprehensive changes in gene expression30,88. Much of plant photomorphogenesis is regulated via conserved modules, which are named after the originally identified components (Fig. 2). In the first module, COP1 acts with SUPPRESSOR OF PHYA (SPA) proteins to degrade a positive regulator HY5 in the dark89–91. In the presence of red or blue light, the COP1/SPA complex is inactivated by phytochromes and cryptochromes89,92, leading to the accumulation of HY5 and the induction of photomorphogenesis. Interestingly, UVR8 promotes photomorphogenesis through an alternative mechanism whereby UV-B activated UVR8 monomers associate with the COP1/SPA complex to promote HY5 accumulation93. The COP1/SPA complex also degrades CONSTANS, an essential component of the photoperiodic flowering pathway (see the section 'Photoperiodic control of flowering time'), and PIFs94. PIFs form the second regulatory hub94 and are also directly bound and inactivated by both phytochromes and cryptochromes; UVR8 indirectly inhibits PIF accumulation by repressing PIF transcription95–101. PIFs have important roles in regulating genes necessary for photomorphogenesis, but are rapidly degraded in the presence of light94. In addition, the light-induced degradation of PIFs can be limited by far-red light, thereby allowing PIFs to direct aspects of the shade avoidance response102,103. In combination, the COP1 and PIF signalling hubs integrate environmental information to control gene expression89,94.

Light-induced pigments

Phenylpropanoids

Fruit quality is typically dependent upon the health of the bearing plants, although direct light irradiation also alters their biochemical composition66. One of the principle determinants of fruit quality is the accumulation of phenylpropanoids (including flavonols, anthocyanins, and proanthocyanidins), which alter the color, aroma, astringency, and antioxidant properties of fruit104. Importantly, light can have dramatic effects upon the quantity and types of flavonoids that accumulate (reviewed by66), although it should be noted that centuries of selective breeding have altered the specific responses of our crops (for example red vs. green apples105).

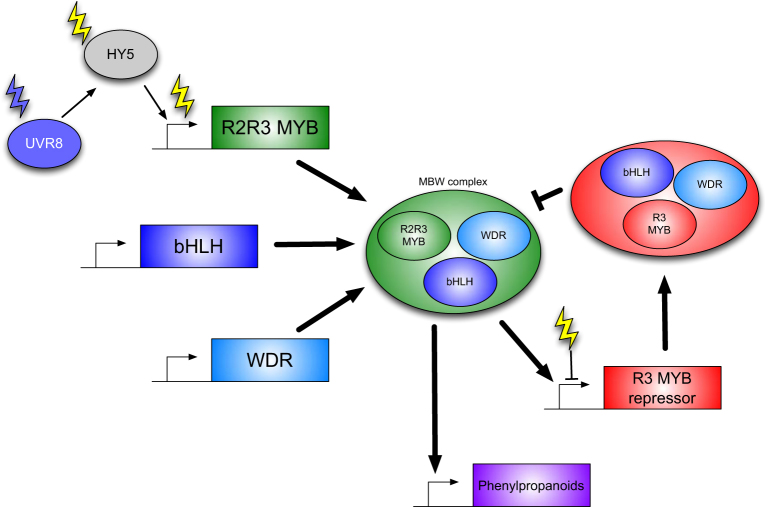

The spatial and temporal induction of phenylpropanoid metabolism occurs both post-transcriptionally and post-translationally via a conserved agglomeration of R2R3 MYB, bHLH, and WDR transcription factors known as the MBW complex (Fig. 366,106–109). Regulation of the MBW complex by light subsequently leads to the altered accumulation of phenylpropanoids, although additional R3 MYBs are also capable of binding to the MBW complex to limit its activity110. For example, the R2R3 MYB transcription factor PAP1 is degraded by the COP1/SPA complex in the dark, leading to reduced anthocyanin accumulation (Figs. 2 and 3111), while UV-B light (via UVR8) induces transcription of R2R3 MYBs that induce flavonol accumulation in Arabidopsis and grape112,113. Interestingly, accumulation of phenylpropanoids can be increased by manipulating photoreceptor abundance in transgenic tomato and strawberry fruits, suggesting that activation of these photoreceptors using specific wavelengths of light could improve the nutritional value of fruits114,115.

Fig. 3. Phenylpropanoids accumulation can be induced by light.

Phenylpropanoid accumulation is regulated by a conserved regulatory module comprising a R2R3 MYB, a bHLH, and a WDR transcription factor. Together these three proteins comprise the MBW complex that activates transcription of enzymes necessary for phenylpropanoid production. Of these three proteins, developmental and environmental induction of R2R3 MYBs is regulated to control MBW activity, in part via the transcription factor HY5. UVR8 stabilizes HY5 through modulation of the COP1/SPA complex, while other photoreceptors promote HY5 stability indirectly or act independently of HY5 (See Fig. 2). Additional control commonly occurs via feedback loops including closely related R3 MYBs that serve to repress MBW activity. R3 MYB transcription can be regulated by the MBW itself, or be independently repressed by light or other environmental and developmental signals. Genes are represented by rectangles, proteins by ovals. Green complexes activate gene expression, red components repress MBW activity. bHLH basic HELIX LOOP HELIX, HY5 ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL5, MBW MYB/bHLH/WDR complex, UVR8 UVB RESISTANCE LOCUS8

Carotenoids

In addition to the regulation of phenylpropanoids, light also regulates the production of carotenoids as part of photomorphogenesis116,117. While carotenoids play a vital role in photosynthesis as part of the light harvesting complex118, they have also been adopted as photoprotectants, and have additional roles in growth and development118. In horticulture, carotenoids are valued as a valuable source of anti-oxidants and essential dietary precursors that accumulate in fruits and vegetables as they ripen118,119.

Light has been observed to affect carotenoid biosynthesis in a number of species during fruit ripening and flower development120,121. The carotenoid biosynthetic pathway is complex, and thoroughly reviewed elsewhere118. It is important to note, however, that one of the rate-limiting enzymes necessary for carotenoid biosynthesis, PHYTOENE SYNTHASE (PSY), is regulated by light. PSY activity is reversibly induced by red light, suggesting a role for phytochromes in this response122. It is likely that this regulation acts via COP1 (Fig. 2), as transgenic tomato fruits with reduced COP1 or HY5 transcript accumulation had altered carotenoid content123, although light induction of PSY transcript has also been reported in some species124. Encouragingly, studies using transgenic tomato to over-express phytochromes and cryptochromes observed increased carotenoid accumulation in transgenic fruits114,125, suggesting that enhancement of photoreceptor signalling could be sufficient to induce carotenoid accumulation.

Shade avoidance

Modern horticulture requires plants to be grown in close proximity so as to generate a commercially-viable harvest, inevitably inducing a shade avoidance response as plants seek to outcompete their neighbors. Importantly, plants perceive and respond to changes in light quality before they are shaded, ensuring that most crops are responding to shade even if direct shading is avoided102,126. Plants absorb light in a wavelength-dependent manner, absorbing light in the UV and photosynthetically active portions of the spectrum (although comparatively less green) while reflecting far-red and infra-red light. As a consequence, plants are able to perceive shade as a change in either the quality or quantity of light102,127,128. Given phytochromes’ sensitivity to red/far-red light (see the section 'Phytochromes'), much research regarding shade avoidance (and consequently our understanding) concerns the role of these photoreceptors in mediating this response102,126. It is, however, important to note the role of blue, green, and UV portions of the spectra in governing plants responses to shade63,98,128.

Shade avoidance has many consequences for plant growth, ranging from leaf hyponasty (leaf movement), stem or petiole elongation, and directional growth away from shade of actively growing tissues, through to architectural changes such as reduced branching and increased leaf senescence that reduces resources devoted to shaded leaves102,129,130. These developmental changes ensure that plants are able to exploit any gaps in the canopy while also promoting vertical growth to over-shadow neighboring plants. Such developmental changes can also culminate in an acceleration to flowering in some species, with inactivation of phytochromes by far-red enriched light relieving repression of photoperiodic flowering (see the section 'Photoperiodic control of flowering time', 131–133). In commercial applications, such behavioral changes can potentially culminate in reduced yield, or in increased crop management (e.g., pruning) to minimize these consequences134,135, although such effects can be mitigated through the choice of alternate varieties.

Photoperiodic control of flowering time

As part of the maturation process, plants undergo a transition to flowering that is largely irreversible136. The floral transition is consequently tightly regulated, with plants integrating day-length, age, and temperature cues to determine flowering time. These pathways combine to control the accumulation of FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), which is the florigen transported from the leaves to the shoot apical meristem to initiate the floral transition in numerous species137,138. Given the importance of flowering to agriculture and horticulture, considerable time has been spent elucidating the molecular pathways underlying this control, although only light-induced pathways are considered here80.

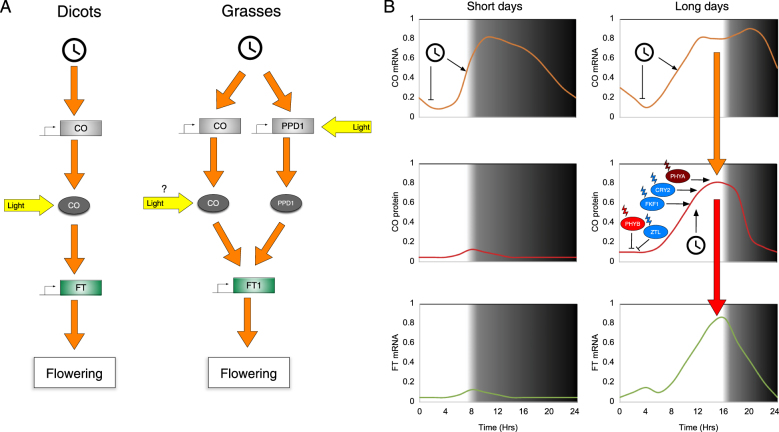

Flowering time in response to day-length is explained by the external co-incidence model, which is conserved across a wide-range of species (Fig. 480). Transcription of a transcriptional activator, CONSTANS (CO), is controlled by the circadian system so that the protein accumulates during the late afternoon80,137,139. In particular, CYCLING DOF FACTORs (CDFs) prevent transcription of CO, but are degraded via a blue light-dependent pathway mediated by FKF1 in long days, allowing CO to accumulate under inductive conditions52. Importantly, CO protein is stabilized by blue or far-red light, with additional control mediated by clock-regulated factors140–142. This light-dependent regulation ensures that CO only accumulates in long days, and so FT transcription is limited to these permissive conditions in long day plants. Interestingly, red light limits CO accumulation in the morning140,143,144 suggesting that flowering may be suppressed in the absence of shade. Although Arabidopsis CO arose from a duplication during the divergence of the Brassicaceae, numerous examples indicate that regulation of FT by CO orthologues is a common consequence of convergent evolution145–147. For instance, a CO orthologue, Hd1, has been co-opted as a floral repressor in rice, a short day species148.

Fig. 4. The floral transition is regulated by light.

a Molecular control of photoperiodic flowering has arisen multiple times during evolution, but commonly requires circadian control of CONSTANS (CO) transcription. Post-translational stabilization of CO enables the transcription of FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), which induces the floral transition in the meristem. An additional pathway has been described in grasses, where PHOTOPERIOD1 (PPD1) transcription is induced by light and the clock. Both PPD1 and CO activate FT transcription in these species. b The external coincidence model explains how long day plants flower under inductive conditions. CO transcript (orange line, top) accumulates during the evening, but CO protein (red line, middle) only accumulates in the presence of light, when photoreceptors are necessary to inhibit CO degradation by COP1. Stabilization of CO protein in long days enables transcription of FT, culminating in floral transition. See also see the section 'Photoperiodic control of flowering time' and Fig. 2. Boxes indicate transcriptional targets, ovals represent protein. CO CONSTANS, CRY cryptochrome, FKF1 FLAVIN BINDING KELCH REPEAT F-BOX1, FT FLOWERING LOCUS T, PPD1 PHOTOPERIOD1, PHY phytochrome, ZTL ZEITLUPE

Additional photoperiodic flowering pathways have been identified in grasses such as barley and wheat (Fig. 4a). In these species PHOTOPERIOD 1 (PPD1), a gene that arose from a duplication of a circadian clock gene after the divergence of the grasses, is important to integrate circadian and photoperiod information149–151. PPD1 is expressed in the light via phytochrome C (phyC), and subsequently acts to promote expression of the FT homologue FLOWERING LOCUS T1 (FT1)151–153. This pathway appears to act in addition to the CONSTANS-mediated pathway, although the relationship between CO-derived and PPD1-derived pathways remains to be fully tested139. It remains to be determined whether pathways analogous to PPD1 have arisen outwith the grasses.

Improving crop yield using light

As light is a prerequisite for photosynthesis (and consequently plant growth) supplemental lighting is typically used to accelerate plant development154–156. Growers face many challenges in providing optimal lighting, with shade, cloud cover, and changing seasons introducing heterogeneity in both the spatial and temporal distribution of light. Given the broad range of light qualities perceived by plants it is apparent that at least one source of broad spectrum light should be provided (either from natural illumination, metal halide (MH), and High Pressure Sodium (HPS) lights, or from white or multi-spectral LED arrays). Beyond this requirement, many opportunities exist to manipulate the precise light environment used for plant growth to stimulate desirable plant development (such as fruit quality or delaying flowering to promote vegetative growth).

Supplemental overhead lighting has been used in glasshouses for many years to increase crop production during periods of low natural light, either to extend shorter winter days or during periods of inclement weather154,156. In general, a 1% increase in lighting provides a 1% increase in yield, although interactions between light and other factors (such as temperature and CO2) complicate this relationship157. Despite these obvious opportunities, numerous studies emphasize the varied responses of different crops to supplemental lighting regimes. It is also important to note that periods of darkness are often required to prevent chlorosis or impaired leaf development158–162. As a consequence it will be important to develop light regimes optimized for specific crops, with consideration of the local natural lighting environment, rather than applying a uniform lighting regime.

Supplemental lighting and spectral manipulation

The development of LEDs that are cost effective to install at commercial scales exponentially increases the options available to growers as they seek to improve crop yield, with the opportunity to specify the quality, quantity, uniformity, and duration of light used163. LEDs also irradiate much less heat that their metal halide (MH) and high pressure sodium (HPS) predecessors, enabling novel strategies such as intra-canopy lighting to provide more uniform light throughout the canopy. Numerous studies demonstrate the utility of supplemental lighting, with improvements in crops ranging from lettuce leaves to the fruits of strawberries, cucumbers, sweet peppers, and tomatoes164–167. For instance, illumination of peppers with light was sufficient to induce color break, greatly improving commercial value168, while altering the ratio of blue and red light used to irradiate lambs lettuce (Valerianella locusta) improved yield and both sugar and phenol content of harvested leaves165. The individual sensitivities of plant photoreceptor families enables plant growth and development to be precisely controlled by changing the proportion of red/far-red/blue/UV LEDs used, with these light conditions changing plant architecture and flowering via pathways summarized in the ̔Plant development is controlled by light ʼ section. In future it will be necessary to refine our understanding of photoreceptor function in crops so that light regimes (including the precise light spectra used) can be optimized to improve yield and quality.

Photoperiod extension

Perhaps the simplest utilization of supplemental lighting is to extend day length during the winter months. In some day neutral species, such as sweet peppers, day length extension photoperiod increased fruit yield, although comparable increases were not observed in closely related Solanaceae, such as tomatoes160. Interestingly, light quality has a profound effect on plant growth. For instance, the use of blue LEDs at the end of day improve tomato quality (although not yield169). As a consequence, it will be of great benefit to understand how photoreceptors contribute to these yield and quality phenotypes. Such knowledge will enable more a systematic approach to specifying light regimes for specific crops. This specification will depend upon both the local light environment and the qualities desired in the crop.

Intracanopy lighting

The higher energy efficiency of LEDs ensures that they are much cooler than their MH and HPS equivalents170. This allows LEDs to be interspersed within a canopy to ensure greater light distribution throughout a densely planted crop. This has multiple benefits, ranging from greater light use efficiency (and therefore reduced energy consumption171), to increase uniformity, quality, and yield of fruit166,167. Intracanopy lighting could also be used to control plant architecture; for instance supplemental red light could be used to minimize internode elongation and leaf drop as part of a shade avoidance response. This has particular relevance for leaf crops such as lettuce, where supplemental lighting has been used to limit senescence, thereby enhancing yield172.

Night breaks

Beyond the utilization of supplemental lighting to extend day length and increase the distribution of light in the canopy, short periods of light during the night have been successfully used to manipulate plant development. In short day plants, such as Chrysanthemum and Ipomoea nil, night breaks using red light can be used to delay flowering173–175. Conversely, night breaks can be used to accelerate flowering in long day plants176. In tomato, red light night breaks induced a delay in flowering and decreased plant height while also improving tomato fresh weigh shortly after flowering177. These differences in flowering and plant morphology are most likely derived from activation of phytochromes (which would otherwise revert to their inactive state in the dark—see the section 'Phytochromes') and it is likely such phenomena will also be observed in other species.

Post-harvest lighting regimes

Supplemental lighting can also be used after harvesting to prolong shelf-life or to alter the biochemical properties of the crop. For instance, irradiation with white LEDs was sufficient to delay senescence and therefore promote the shelf life of harvested sprouts178, whereas irradiation of sweet peppers after harvesting was sufficient to induce color break, thereby enhancing market value179. Interestingly, maintenance of circadian rhythms through the utilization of light:dark cycles delays senescence compared to constantly lit conditions, demonstrating the need for further research to more thoroughly understand how complex lighting regimes can be utilized to improve storage of harvested crops180.

Future perspectives

Plants have evolved a sophisticated network of photoreceptors that enable them to perceive and respond to environmental change. As commercial scale installation of LEDs becomes viable, the on-going challenge facing commercial growers will be the optimization of lighting regimes to promote desirable qualities for glasshouse management and crop quality, while also considering the economic costs of LED installation and the specific photoresponsive traits of their crop. Although there are numerous examples of diversification of regulatory pathways, it is reassuring that the photoreceptors and key downstream regulatory modules regulating flowering time, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, and carotenoid production are conserved. Such conservation demonstrates that it will be possible to utilize the understanding gained from model species to design tailored light regimes optimized for many glasshouse-grown crops, leading to improved yield and quality in the future.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the University of Essex for funding this work.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Cooper AJ. Observations on the seasonal trends in the growth of the leaves and fruit of glasshouse tomato plants, considered in relation to light duration and plant age. J. Hortic. Sci. 1961;36:55–69. doi: 10.1080/00221589.1961.11514000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darko E, Heydarizadeh P, Schoefs B, Sabzalian MR. Photosynthesis under artificial light: the shift in primary and secondary metabolism. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2014;369:20130243. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang LY, et al. Effects of light quality on growth and development, photosynthetic characteristics and content of carbohydrates in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) plants. Photosynthetica. 2017;55:467–477. doi: 10.1007/s11099-016-0668-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones MA. Interplay of circadian rhythms and light in the regulation of photosynthesis-derived metabolism. Progress. Bot. 2017;79:147–171. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J, Terzaghi W, Deng XW. Genomic basis for light control of plant development. Protein Cell. 2012;3:106–116. doi: 10.1007/s13238-012-2016-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitelam, G. C. & Halliday, K. J. Light and Plant Development. Annual Plant Reviews 30 (Blackwell Publishing, UK, 2007).

- 7.Briggs, W. R. & Spudich, J. L. Handbook of Photosensory Receptors. (Wiley-VCH, Germany, 2005).

- 8.Rockwell NC, Su YS, Lagarias JC. Phytochrome structure and signalling mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 2006;57:837–858. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christie JM, Blackwood L, Petersen J, Sullivan S. Plant flavoprotein photoreceptors. Plant Cell Phys. 2015;56:401–413. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li QH, Yang HQ. Cryptochrome signaling in plants. Photochem. Photobiol. 2007;83:94–101. doi: 10.1562/2006-02-28-IR-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Briggs WR. The LOV domain: a chromophore module servicing multiple photoreceptors. J. Biomed. Sci. 2007;14:499–504. doi: 10.1007/s11373-007-9162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jenkins GI. Photomorphogenic responses to ultraviolet-B light. Plant, Cell Environ. 2017;40:2544–2557. doi: 10.1111/pce.12934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Folta KM. Contributions of green light to plant growth and development. Am. J. Bot. 2013;100:70–78. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1200354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler WL, Norris KH, Seigelman HW, Hendricks SB. Detection, assay and preliminary purification of the pigment controlling photoresponsive development of plants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1959;45:1703–1708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.45.12.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rockwell NC, Su YS, Lagarias JC. Phytochrome structure and signaling mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 2006;57:837–858. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huq, E. & Quail, P. H. in Handbook of Photosensory Receptors (eds W. R. Briggs & J. L. Spudich) Ch. 7, 151–170 (Wiley-VCH, Germany, 2005).

- 17.Mathews S, Sharrock RA. Phytochrome gene diversity. Plant Cell & Environment. 1997;20:666–671. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1997.d01-117.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casal JJ, Yanovsky MJ, Luppi JP. Two photobiological pathways of phytochrome A activity, only one of which shows dominant negative suppression by phytochrome B. Photochem. Photobiol. 2000;71:481–486. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2000)071<0481:TPPOPA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharrock RA, Clack T. Patterns of expression and normalized levels of the five arabidopsis phytochromes. Plant Physiol. 2002;130:442–456. doi: 10.1104/pp.005389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franklin KA, Larner VS, Whitelam GC. The signal transducing photoreceptors of plants. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2005;49:653–664. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.051989kf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schafer E, Bowler C. Phytochrome-mediated photoperception and signal transduction in higher plants. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:1042–1048. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daiyasu H, et al. Identification of cryptochrome DASH from vertebrates. Genes Cells. 2004;9:479–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin C, Ahmad M, Chan J, Cashmore AR. CRY2, a second member of the Arabidopsis cryptochrome gene family (accession No. U43397) (PGR 96-001) Plant Physiol. 1996;110:1047. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.3.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleine T, Lockhart P, Batschauer A. An Arabidopsis protein closely related to Synechocystis cryptochrome is targeted to organelles. Plant J. 2003;35:93–103. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmad M, Cashmore AR. HY4 gene of A. thaliana encodes a protein with characteristics of a blue-light photoreceptor. Nature. 1993;366:162–166. doi: 10.1038/366162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaves I, et al. The cryptochromes: blue light photoreceptors in plants and animals. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 2011;62:335–364. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Q, et al. Photoactivation and inactivation of Arabidopsis cryptochrome 2. Science. 2016;354:343–347. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf9030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin C, et al. Enhancement of blue-light sensitivity of Arabidopsis seedlings by a blue light receptor cryptochrome 2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:2686–2690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu X, et al. Arabidopsis cryptochrome 2 completes its posttranslational life cycle in the nucleus. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3146–3156. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.053017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma L, et al. Light control of Arabidopsis development entails coordinated regulation of genome expression and cellular pathways. Plant Cell. 2001;13:2589–2607. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.12.2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiao Y, et al. A genome-wide analysis of blue-light regulation of Arabidopsis transcription factor gene expression during seedling development. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:1480–1493. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.029439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmad M, Lin C, Cashmore AR. Mutations throughout an Arabidopsis blue-light photoreceptor impair blue-light-responsive anthocyanin accumulation and inhibition of hypocotyl elongation. Plant J. 1995;8:653–658. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.08050653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu H, et al. Photoexcited CRY2 interacts with CIB1 to regulate transcription and floral initiation in Arabidopsis. Science. 2008;322:1535–1539. doi: 10.1126/science.1163927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu H, Liu B, Zhao C, Pepper M, Lin C. The action mechanisms of plant cryptochromes. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:684–691. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gallagher S, Short TW, Ray PM, Pratt LH, Briggs WR. Light-mediated changes in two proteins found associated with plasma membrane fractions from pea stem sections. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:8003–8007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.8003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huala E, et al. Arabidopsis NPH1: a protein kinase with a putative redox-sensing domain. Science. 1997;278:2120–2123. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Briggs WR, et al. The phototropin family of photoreceptors. Plant Cell. 2001;13:993–997. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.5.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Briggs WR, Christie JM, Salomon M. Phototropins: a new family of flavin-binding blue light receptors in plants. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2001;3:775–788. doi: 10.1089/15230860152664975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kagawa T, et al. Arabidopsis NPL1: a phototropin homolog controlling the chloroplast high-light avoidance response. Science. 2001;291:2138–2141. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5511.2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Briggs WR, Christie JM. Phototropins 1 and 2: versatile plant blue-light receptors. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:204–210. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohgishi M, Saji K, Okada K, Sakai T. Functional analysis of each blue light receptor, cry1, cry2, phot1, and phot2, by using combinatorial multiple mutants in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:2223–2228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305984101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Christie JM. Phototropin blue-light receptors. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 2007;58:21–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.103951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lariguet P, Dunand C. Plant photoreceptors: phylogenetic overview. J. Mol. Evol. 2005;61:559–569. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0294-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang K, Merkle T, Beck CF. Isolation and characterization of a Chlamydomonas gene that encodes a putative blue-light photoreceptor of the phototropin family. Physiol. Plant. 2002;115:613–622. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1150416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nozue K, et al. A phytochrome from the fern Adiantum with features of the putative photoreceptor NPH1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:15826–15830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suetsugu N, Mittmann F, Wagner G, Hughes J, Wada M. A chimeric photoreceptor gene, NEOCHROME, has arisen twice during plant evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:13705–13709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504734102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawai H, et al. Responses of ferns to red light are mediated by an unconventional photoreceptor. Nature. 2003;421:287–290. doi: 10.1038/nature01310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Somers DE, Schultz TF, Milnamow M, Kay SA. ZEITLUPE encodes a novel clock-associated PAS protein from Arabidopsis. Cell. 2000;101:319–329. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80841-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nelson DC, Lasswell J, Rogg LE, Cohen MA, Bartel B. FKF1, a clock-controlled gene that regulates the transition to flowering in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2000;101:331–340. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80842-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schultz TF, Kiyosue T, Yanovsky M, Wada M, Kay SA. A role for LKP2 in the circadian clock of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2001;13:2659–2670. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.12.2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Somers DE. Clock-associated genes in Arabidopsis: a family affair. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2001;356:1745–1753. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sawa M, Nusinow DA, Kay SA, Imaizumi T. FKF1 and GIGANTEA complex formation is required for day-length measurement in Arabidopsis. Science. 2007;318:261–265. doi: 10.1126/science.1146994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim WY, et al. ZEITLUPE is a circadian photoreceptor stabilized by GIGANTEA in blue light. Nature. 2007;449:356–360. doi: 10.1038/nature06132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Song YH, et al. Distinct roles of FKF1, Gigantea, and Zeitlupe proteins in the regulation of constans stability in Arabidopsis photoperiodic flowering. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:17672–17677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415375111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Imaizumi, T., Schultz, T. F., Harmon, F. G., Ho, L. A. & Kay, S. A. FKF1 F-box protein mediates cyclic degradation of a repressor of CONSTANS in Arabidopsis. Science 309, 293–296 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Tilbrook K, et al. The UVR8 UV-B photoreceptor: perception, signaling and response. The Arabidopsis book /Am Soc Plant Biologists. 2013;11:e0164. doi: 10.1199/tab.0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rizzini L, et al. Perception of UV-B by the Arabidopsis UVR8 protein. Science. 2011;332:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.1200660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu D, et al. Structural basis of ultraviolet-B perception by UVR8. Nature. 2012;484:214–219. doi: 10.1038/nature10931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kliebenstein DJ, Lim JE, Landry LG, Last RL. Arabidopsis UVR8 regulates ultraviolet-B signal transduction and tolerance and contains sequence similarity to human regulator of chromatin condensation 1. Plant Physiol. 2002;130:234–243. doi: 10.1104/pp.005041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liang T, et al. UVR8 Interacts with BES1 and BIM1 to regulate transcription and photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell. 2018;44:512–523.e515. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang Y, et al. UVR8 interacts with WRKY36 to regulate HY5 transcription and hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. Nat. Plants. 2018;4:98–107. doi: 10.1038/s41477-017-0099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brown BA, Jenkins GI. UV-B signaling pathways with different fluence-rate response profiles are distinguished in mature Arabidopsis leaf tissue by requirement for UVR8, HY5, and HYH. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:576–588. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.108456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Favory JJ, et al. Interaction of COP1 and UVR8 regulates UV-B-induced photomorphogenesis and stress acclimation in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2009;28:591–601. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wargent JJ, Jordan BR. From ozone depletion to agriculture: understanding the role of UV radiation in sustainable crop production. New Phytol. 2013;197:1058–1076. doi: 10.1111/nph.12132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ballaré CL, Mazza CA, Austin AT, Pierik R. Canopy light and plant health. Plant Physiol. 2012;160:145–155. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.200733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zoratti L, Karppinen K, Luengo Escobar A, Häggman H, Jaakola L. Light-controlled flavonoid biosynthesis in fruits. Front. Plant Sci. 2014;5:534. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Davey MP, et al. The UV-B photoreceptor UVR8 promotes photosynthetic efficiency in Arabidopsis thaliana exposed to elevated levels of UV-B. Photo. Res. 2012;114:121–131. doi: 10.1007/s11120-012-9785-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moriconi, V. et al. Perception of sunflecks by the UV-B photoreceptor UV RESISTANCE LOCUS 8. Plant Physiol., 10.1104/pp.18.00048 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Wigge PA. Ambient temperature signalling in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2013;16:661–666. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Quint M, et al. Molecular and genetic control of plant thermomorphogenesis. Nat. Plants. 2016;2:15190. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2015.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jung JH, et al. Phytochromes function as thermosensors in Arabidopsis. Science. 2016;354:886–889. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Legris M, et al. Phytochrome B integrates light and temperature signals in Arabidopsis. Science. 2016;354:897–900. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fujii Y, et al. Phototropin perceives temperature based on the lifetime of its photoactivated state. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:9206–9211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704462114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jones M. Entrainment of the Arabidopsis circadian clock. J. Plant Biol. 2009;52:202–209. doi: 10.1007/s12374-009-9030-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hsu PY, Harmer SL. Wheels within wheels: the plant circadian system. Trends Plant Sci. 2014;19:240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Covington MF, Maloof JN, Straume M, Kay SA, Harmer SL. Global transcriptome analysis reveals circadian regulation of key pathways in plant growth and development. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R130. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-8-r130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tóth R, et al. Circadian clock-regulated expression of phytochrome and cryptochrome genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:1607–1616. doi: 10.1104/pp.010467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mockler T, et al. The DIURNAL project: DIURNAL and circadian expression profiling, model-based pattern matching, and promoter analysis. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2007;72:353–363. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2007.72.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Millar AJ. Input signals to the plant circadian clock. J. Exp. Bot. 2004;55:277–283. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Song YH, Shim JS, Kinmonth-Schultz HA, Imaizumi T. Photoperiodic flowering: time measurement mechanisms in leaves. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015;66:441–464. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043014-115555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Devlin P, Kay S. Cryptochromes are required for phytochrome signaling to the circadian clock but not for rhythmicity. Plant Cell. 2000;12:2499–2510. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.12.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Somers D, Devlin P, Kay S. Phytochromes and cryptochromes in the entrainment of the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Science. 1998;282:1488–1490. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jones M, Hu W, Litthauer S, Lagarias JC, Harmer SL. A constitutively active allele of phytochrome B maintains circadian robustness in the absence of light. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:814–825. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Baudry A, et al. F-box proteins FKF1 and LKP2 act in concert with ZEITLUPE to control Arabidopsis clock progression. Plant Cell. 2010;22:606–622. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.072843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang L, Fujiwara S, Somers DE. PRR5 regulates phosphorylation, nuclear import and subnuclear localization of TOC1 in the Arabidopsis circadian clock. EMBO J. 2010;29:1903–1915. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fankhauser C, Chory J. Light control of plant development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1997;13:203–229. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Leduc N, et al. Light signaling in bud outgrowth and branching in plants. Plants. 2014;3:223–250. doi: 10.3390/plants3020223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Brown BA, et al. A UV-B-specific signaling component orchestrates plant UV protection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:18225–18230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507187102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lau OS, Deng XW. The photomorphogenic repressors COP1 and DET1: 20 years later. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:584–593. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Osterlund MT, Hardtke CS, Wei N, Deng XW. Targeted destabilization of HY5 during light-regulated development of Arabidopsis. Nature. 2000;405:462–466. doi: 10.1038/35013076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Laubinger S, Fittinghoff K, Hoecker U. The SPA quartet: a family of WD-repeat proteins with a central role in suppression of photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2004;16:2293–2306. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.024216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yi C, Deng XW. COP1 - from plant photomorphogenesis to mammalian tumorigenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:618–625. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Huang X, et al. Conversion from CUL4-based COP1-SPA E3 apparatus to UVR8-COP1-SPA complexes underlies a distinct biochemical function of COP1 under UV-B. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:16669–16674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316622110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Leivar P, Monte E. PIFs: systems integrators in plant development. Plant Cell. 2014;26:56–78. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.120857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kikis EA, Oka Y, Hudson ME, Nagatani A, Quail PH. Residues clustered in the light-sensing knot of phytochrome B are necessary for conformer-specific binding to signaling partner PIF3. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Oka Y, Matsushita T, Mochizuki N, Quail PH, Nagatani A. Mutant screen distinguishes between residues necessary for light-signal perception and signal transfer by phytochrome B. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Oka Y, et al. Functional analysis of a 450-amino acid N-terminal fragment of phytochrome B in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2004;16:2104–2116. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.022350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pedmale UV, et al. Cryptochromes interact directly with PIFs to control plant growth in limiting blue light. Cell. 2016;164:233–245. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ma D, et al. Cryptochrome 1 interacts with PIF4 to regulate high temperature-mediated hypocotyl elongation in response to blue light. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:224–229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511437113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ni W, et al. A mutually assured destruction mechanism attenuates light signaling in Arabidopsis. Science. 2014;344:1160–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.1250778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hayes S, et al. UV-B perceived by the UVR8 photoreceptor inhibits plant thermomorphogenesis. Curr. Biol. 2017;27:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Casal JJ. Photoreceptor signaling networks in plant responses to shade. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013;64:403–427. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Leivar P, Quail PH. PIFs: pivotal components in a cellular signaling hub. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.He J, Giusti MM. Anthocyanins: natural colorants with health-promoting properties. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2010;1:163–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.food.080708.100754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Feng F, Li M, Ma F, Cheng L. Phenylpropanoid metabolites and expression of key genes involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis in the shaded peel of apple fruit in response to sun exposure. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013;69:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Albert NW, et al. A conserved network of transcriptional activators and repressors regulates anthocyanin pigmentation in eudicots. Plant Cell. 2014;26:962–980. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.122069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liu J, Osbourn A, Ma P. MYB transcription factors as regulators of phenylpropanoid metabolism in plants. Mol. Plant. 2015;8:689–708. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Feller A, Machemer K, Braun EL, Grotewold E. Evolutionary and comparative analysis of MYB and bHLH plant transcription factors. Plant J. 2011;66:94–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Quattrocchio F, Wing JF, van der Woude K, Mol JN, Koes R. Analysis of bHLH and MYB domain proteins: species-specific regulatory differences are caused by divergent evolution of target anthocyanin genes. Plant J. 1998;13:475–488. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Xu W, Dubos C, Lepiniec L. Transcriptional control of flavonoid biosynthesis by MYB-bHLH-WDR complexes. Trends Plant Sci. 2015;20:176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Maier A, et al. Light and the E3 ubiquitin ligase COP1/SPA control the protein stability of the MYB transcription factors PAP1 and PAP2 involved in anthocyanin accumulation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2013;74:638–651. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Stracke R, et al. The Arabidopsis bZIP transcription factor HY5 regulates expression of the PFG1/MYB12 gene in response to light and ultraviolet-B radiation. Plant, Cell Environ. 2010;33:88–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Liu L, Gregan S, Winefield C, Jordan B. From UVR8 to flavonol synthase: UV-B-induced gene expression in Sauvignon blanc grape berry. Plant, Cell Environ. 2014;38:905–919. doi: 10.1111/pce.12349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Giliberto L, et al. Manipulation of the blue light photoreceptor cryptochrome 2 in tomato affects vegetative development, flowering time, and fruit antioxidant content. Plant Physiol. 2005;137:199–208. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.051987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kadomura-Ishikawa Y, Miyawaki K, Noji S, Takahashi A. Phototropin 2 is involved in blue light-induced anthocyanin accumulation in Fragaria x ananassa fruits. J. Plant Res. 2013;126:847–857. doi: 10.1007/s10265-013-0582-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Welsch R, Beyer P, Hugueney P, Kleinig H, von Lintig J. Regulation and activation of phytoene synthase, a key enzyme in carotenoid biosynthesis, during photomorphogenesis. Planta. 2000;211:846–854. doi: 10.1007/s004250000352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Meier S, Tzfadia O, Vallabhaneni R, Gehring C, Wurtzel ET. A transcriptional analysis of carotenoid, chlorophyll and plastidial isoprenoid biosynthesis genes during development and osmotic stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Syst. Biol. 2011;5:77. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-5-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nisar N, Li L, Lu S, Khin NC, Pogson BJ. Carotenoid metabolism in plants. Mol. Plant. 2015;8:68–82. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Grierson, D., Purton, M., Knapp, J. & Bathgate, B. Tomato Developmental Mutants (H. Thomas & D. Grierson eds) 77–94 (Cambridge University Press, 1987).

- 120.Giovannoni JJ. Plant Cell. 2004. Genetic regulation of fruit development and ripening; pp. S170–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Adams-Phillips L, Barry C, Giovannoni J. Signal transduction systems regulating fruit ripening. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Schofield A, Paliyath G. Modulation of carotenoid biosynthesis during tomato fruit ripening through phytochrome regulation of phytoene synthase activity. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2005;43:1052–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Liu Y, et al. Manipulation of light signal transduction as a means of modifying fruit nutritional quality in tomato. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:9897–9902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400935101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.von Lintig J, et al. Light-dependent regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis occurs at the level of phytoene synthase expression and is mediated by phytochrome in Sinapis alba and Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. Plant J. 1997;12:625–634. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Boylan MT, Quail PH. Oat phytochrome is biologically active in transgenic tomatoes. Plant Cell. 1989;1:765–773. doi: 10.1105/tpc.1.8.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Casal JJ. Shade avoidance. Arab. Book /Am. Soc. Plant Biol. 2012;10:e0157. doi: 10.1199/tab.0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ballare CL, scopel AL, Sanchez A. Photocontrol of stem elongation in plant neighbourhoods: effects of photon fluence rate under natural conditions of radiation. Plant, Cell Environ. 1991;14:57–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1991.tb01371.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zhang T, Maruhnich SA, Folta KM. Green light induces shade avoidance symptoms. Plant Physiol. 2011;157:1528–1536. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.180661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Finlayson SA, Krishnareddy SR, Kebrom TH, Casal JJ. Phytochrome regulation of branching in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010;152:1914–1927. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.148833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Rousseaux MC, Hall AJ, sanchez rA. Far-red enrichment and photosynthetically active radiation level influence leaf senescence in field-grown sunflower. Physiol. Plant. 1996;96:217–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1996.tb00205.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wollenberg AC, Strasser B, Cerdán PD, Amasino RM. Acceleration of flowering during shade avoidance in Arabidopsis alters the balance between FLOWERING LOCUS C-mediated repression and photoperiodic induction of flowering. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:1681–1694. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.125468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Cerdán PD, Chory J. Regulation of flowering time by light quality. Nature. 2003;423:881–885. doi: 10.1038/nature01636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Endo M, Nakamura S, Araki T, Mochizuki N, Nagatani A. Phytochrome B in the mesophyll delays flowering by suppressing FLOWERING LOCUS T expression in Arabidopsis vascular bundles. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1941–1952. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.032342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ugarte CC, Trupkin SA, Ghiglione H, Slafer G, Casal JJ. Low red/far-red ratios delay spike and stem growth in wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 2010;61:3151–3162. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Libenson S, Rodriguez VM, Lopez Pereira M, Sanchez RA, Casal JJ. Low-Red-to-far-red-ratios-reaching-the-stem-reduce-grain-yield-in-sunflower. Crop Sci. 2002;42:1180–1185. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2002.1180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Evans LT. Flower induction and the Florigen concept. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 1971;22:265–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.22.060171.002053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Turck F, Fornara F, Coupland G. Regulation and identity of florigen: FLOWERING LOCUS T moves center stage. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008;59:573–594. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Wickland DP, Hanzawa Y. The FLOWERING LOCUS T/TERMINAL FLOWER 1 gene family: functional evolution and molecular mechanisms. Mol. Plant. 2015;8:983–997. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Mulki MA, von Korff M. CONSTANS controls floral repression by up-regulating VERNALIZATION2 (VRN-H2) in barley. Plant Physiol. 2016;170:325–337. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Valverde F, et al. Photoreceptor regulation of CONSTANS protein in photoperiodic flowering. Science. 2004;303:1003–1006. doi: 10.1126/science.1091761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Zuo Z, Liu H, Liu B, Liu X, Lin C. Blue light-dependent interaction of CRY2 with SPA1 regulates COP1 activity and floral initiation in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:841–847. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Hayama R, et al. PSEUDO RESPONSE REGULATORs stabilize CONSTANS protein to promote flowering in response to day length. EMBO J. 2017;36:904–918. doi: 10.15252/embj.201693907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Jang S, et al. Arabidopsis COP1 shapes the temporal pattern of CO accumulation conferring a photoperiodic flowering response. EMBO J. 2008;27:1277–1288. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Lazaro A, Mouriz A, Piñeiro M, Jarillo JA. Red light-mediated degradation of CONSTANS by the E3 ubiquitin ligase HOS1 regulates photoperiodic flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2015;27:2437–2454. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Kurokura T, Samad S, Koskela E, Mouhu K, Hytönen T. Fragaria vesca CONSTANS controls photoperiodic flowering and vegetative development. J. Exp. Bot. 2017;68:4839–4850. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Simon S, Rühl M, de Montaigu A, Wötzel S, Coupland G. Evolution of CONSTANS regulation and function after gene duplication produced a photoperiodic flowering switch in the brassicaceae. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015;32:2284–2301. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Liu XL, Covington MF, Fankhauser C, Chory J, Wagner DR. ELF3 encodes a circadian clock-regulated nuclear protein that functions in an Arabidopsis PHYB signal transduction pathway. Plant Cell. 2001;13:1293–1304. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.6.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Yano M, et al. Hd1, a major photoperiod sensitivity quantitative trait locus in rice, is closely related to the Arabidopsis flowering time gene CONSTANS. Plant Cell. 2000;12:2473–2484. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.12.2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Farré EM, Liu T. The PRR family of transcriptional regulators reflects the complexity and evolution of plant circadian clocks. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2013;16:621–629. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Turner A. The pseudo-response regulator Ppd-H1 provides adaptation to photoperiod in barley. Science. 2005;310:1031–1034. doi: 10.1126/science.1117619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Chen A, et al. Phytochrome C plays a major role in the acceleration of wheat flowering under long-day photoperiod. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:10037–10044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409795111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Shaw LM, Turner AS, Laurie DA. The impact of photoperiod insensitive Ppd-1a mutations on the photoperiod pathway across the three genomes of hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum) Plant J. 2012;71:71–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Nishida H, et al. Phytochrome C is a key factor controlling long-day flowering in barley. Plant Physiol. 2013;163:804–814. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.222570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Heuvelink E, et al. Acta Horticulturae. Leuven, Belgium: International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS); 2006. pp. 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 155.Hao X, Papadopoulos AP. Effects of supplemental lighting and cover materials on growth, photosynthesis, biomass partitioning, early yield and quality of greenhouse cucumber. Sci. Hortic. 1999;80:1–18. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4238(98)00217-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Lu, N. & Mitchell, C. A. Vol. 956 LED Lighting for Urban Agriculture (T. kozai ed) 219–232 (Springer Singapore, 2016).

- 157.Marcelis LFM, et al. Quantification of the growth response to light quantity of greenhouse grown crops. Acta Hortic. 2006;711:97–104. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2006.711.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Demers DA, Gosselin A, Wien HC. Effects of supplemental light duration on greenhouse sweet pepper plants and fruit yields. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1998;123:202–207. [Google Scholar]

- 159.Nilwik HJM. Growth analysis of sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) 2. Interacting effects of irradiance, temperature and plant age in controlled conditions. Ann. Bot. 1981;48:137–145. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a086107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Dorais M, Yelle S, Gosselin A. Influence of extended photoperiod on photosynthate partitioning and export in tomato and pepper plants. N.Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 1996;24:29–37. doi: 10.1080/01140671.1996.9513932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Logendra S, Putman JD, Janes HW. The influence of light period on carbon partitioning, translocation and growth in tomato. Sci. Hortic. 1990;42:75–83. doi: 10.1016/0304-4238(90)90149-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Vézina F, Trudel MJ, Gosselin A. Influence du mode d'utilisation de l'éclairage d'appoint sur la productivité et la physiologie de la tomate de serre. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1991;71:923–932. doi: 10.4141/cjps91-132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Nelson JA, Bugbee B. Economic analysis of greenhouse lighting: light emitting diodes vs. high intensity discharge fixtures. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e99010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Choi HG, Moon BY, Kang NJ. Effects of LED light on the production of strawberry during cultivation in a plastic greenhouse and in a growth chamber. Sci. Hortic. 2015;189:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2015.03.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Wojciechowska R, Długosz-Grochowska O, Kołton A, Żupnik M. Effects of LED supplemental lighting on yield and some quality parameters of lamb's lettuce grown in two winter cycles. Sci. Hortic. (Amst.) 2015;187:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2015.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]