Abstract

Objectives

This study examines the use of expedited approval pathways by Health Canada over the period 1995 to 2016 inclusive and the relationship between the use of these pathways and the therapeutic gain offered by new products.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Data sources

Therapeutic Products Directorate, Biologics and Genetic Therapies Directorate, Notice of Compliance database, Notice of Compliance with conditions web site, Patented Medicine Prices Review Board, La revue Prescrire, WHO Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Percent of new drugs evaluated by Health Canada that went through an expedited pathway between 1995 and 2016 inclusive. Kappa values comparing the review status with assessments of therapeutic value for individual drugs.

Results

Of 623 drugs approved by Health Canada between 1995 and 2016, 438 (70.3%) drugs went through the standard pathway and 185 (29.7%) an expedited pathway. Therapeutic evaluations were available for 509 drugs. Health Canada used an expedited approval pathway for 159 of the 509 drugs, whereas only 55 were judged to be therapeutically innovative. Forty-two of the 55 therapeutically innovative drugs received an expedited review and 13 received a standard review. The Kappa value for the entire period for all 509 drugs was 0.276 (95% CI 0.194 to 0.359) indicating ‘fair’ agreement between Health Canada’s use of expedited pathways and independent evaluations of therapeutic innovation.

Conclusion

Health Canada’s use of expedited approvals was stable over the entire time period. It was unable to reliably predict which drugs will offer major therapeutic gains. The findings in this study should provoke a discussion about whether Health Canada should continue to use these pathways and if so how their use can be improved.

Keywords: health policy, accelerated approvals, health canada, therapeutic evaluation, therapeutic groups

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Cross-sectional analysis of the use of expedited approval pathways by Health Canada over an extended period of time.

Comparison of use of expedited approval pathways with independent assessment of therapeutic evaluation.

Analysis of approvals and therapeutic value of therapeutic subgroups.

Twenty per cent of new drugs approved did not have therapeutic evaluations.

Introduction

In order to obtain authorisation to market a new active substance (NAS, a molecule never marketed before in Canada in any form) in Canada, companies typically file a New Drug Submission (NDS) which includes preclinical and clinical scientific information about the product’s safety, efficacy and quality and information about its claimed therapeutic value, conditions for use and side effects.1 Health Canada then has a 300-day period to evaluate this information and make a decision about whether to allow the product to be sold, that is, whether to issue a Notice of Compliance (NOC).

In an effort to ensure that promising therapies for serious, life-threatening or debilitating illnesses reach Canadians in a timely manner, Health Canada has developed two other pathways for approving NAS. These are described in detail elsewhere,2 but briefly, the first of these is a priority review that involves the company submitting a complete NDS but with a review period of 180 days.3 The second is the Notice of Compliance with conditions (NOC/c)4 whereby Health Canada will give a conditional approval based on limited evidence—phase II clinical trials or trials with only surrogate markers. In return for NOC/c status, companies commit to further studies that definitively establish efficacy and submit the results of these to Health Canada. A failure to complete these studies or negative results from them could lead to the marketing authorisation being cancelled.

Lexchin has examined how closely Health Canada’s use of the two pathways (priority review and NOC/c, hereafter collectively termed expedited review pathways) corresponds to independent assessments of the therapeutic innovation of drugs at the level of individual drugs. For the period 1997–2012, the Kappa value was 0.334 (95% CI 0.220 to 0.447) or fair.5

This current study is a further and more detailed look at how Health Canada uses its expedited review pathways, by extending previous work in a number of ways. First it covers a wider time period, 1995 to 2016, inclusive. Second, it looks at the use of both of the expedited review pathways over this entire time period for the entire sample of drugs as well as subgroups—small molecule drugs, biologics and therapies for serious diseases. Third, it calculates the Kappa values for the entire sample of drugs as well as the subgroups listed above. These subgroups were chosen because small molecules and biologics have fundamentally different characteristics and these may influence a decision to use an expedited review pathway and how accurately Health Canada can predict their therapeutic value. Similarly, when the treatment is for serious medical conditions, Health Canada may be more willing to use an expedited review pathway and may be more likely to believe that the new product will provide a significant therapeutic benefit.

Methods

Data sources

All NAS approved from 1995 to 2016 inclusive were documented using the annual reports from the Therapeutic Products and the Biologics and Genetic Therapies Directorates that are in charge of reviewing applications for new small molecule drugs and biologics and vaccines, respectively. (Reports are available by directly contacting the directorates at publications@hc-sc.gc.ca.) A starting year of 1995 was selected as there are no annual reports from Health Canada prior to that year. Generic and brand names along with the specific approval pathway—standard, priority and NOC/c (NOC/c only from 1998 onwards)—and whether the product was a small molecule drug or biologic (information available only from 2000 onwards) were manually extracted from the annual reports by the author.

Not all of the drugs with a NOC/c are documented in the annual reports and they were supplemented using four additional sources: articles by Lexchin6 and Law,7 the Notice of Compliance database (http://webprod5.hc-sc.gc.ca/noc-ac/index-eng.jsp) and the Notice of Compliance with conditions web site (http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/prodpharma/notices-avis/conditions/index-eng.php). Only NAS approved under a NOC/c were considered; NOC/c for additional indications for existing drugs were excluded. Drugs can receive both a priority and NOC/c review and in this case, they were only counted as receiving a priority review.

Assessment of therapeutic innovation

The therapeutic value of drugs was assessed using the ratings from the annual reports of the Canadian Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) (http://www.pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca/english/View.asp?x=91) and Prescrire International, the English language translation of the French drug bulletin La revue Prescrire.8 The processes that these two organisations use in arriving at their decisions about therapeutic innovation have been previously described.5 For the purpose of this study, products that the PMPRB deemed breakthrough and substantial improvement were termed ‘innovative’ and products in other categories were termed ‘not innovative’ (category 3=moderate, little or no improvement over existing medicines prior to 2010; slight or no improvement, moderate improvement—primary and moderate improvement—secondary from 2010 onward). Prescrire uses seven categories to rate therapeutic innovation. The first two, bravo (major therapeutic innovation in an area where previously no treatment was available) and a real advance (important therapeutic innovation but has limitations) were defined as a significant therapeutic innovation and the other Prescrire categories (except judgement reserved) were defined as no therapeutic advance.

If both the PMPRB and Prescrire evaluated the drug and the ratings were discordant, that is, one said it was not innovative and one said it was, the drug was still considered innovative. Table 1 shows that there is substantial agreement among the definitions used by Health Canada, the PMPRB and Prescrire in assessing therapeutic innovation. Ratings were current for PMPRB as of 31 December 2016 (the annual report for 2017 was not available at the time of writing) and for Prescrire as of 20 February 2018.

Table 1.

Criteria used by Health Canada in determination of priority review or Notice of Compliance with conditions pathway and by Human Drug Advisory Panel and Prescrire in determining innovation status

| Health Canada: criteria for priority review and NOC/c pathway | Human Drug Advisory Panel of Patented Medicine Prices Review Board: – criteria for breakthrough and substantial improvement | Prescrire: criteria for bravo and a real advance |

| Priority review: a serious, life-threatening or severely debilitating illness or condition for which there is substantial evidence of clinical effectiveness that the drug provides: effective treatment, prevention or diagnosis of a disease or condition for which no drug is presently marketed in Canada | Breakthrough: first drug product to treat effectively a particular illness | Bravo: major therapeutic innovation in an area where previously no treatment was available |

| NOC/c pathway: provides patients suffering from serious, life-threatening or severely debilitating diseases or conditions with earlier access to promising new drugs | Substantial improvement: provides a substantial improvement over existing drug products | A real advance: product is an important therapeutic innovation but has certain limitations |

Adapted from.24

NOC/c, Notice of Compliance with conditions.

Data analysis

The number and percent of drugs approved through the standard, priority and NOC/c pathways were calculated for each year and for the 22-year period.

Kappa values were used to compare the review status from Health Canada to the assessments for the same drug from the PMPRB and/or Prescrire for each year and for the 22-year period.

Drugs approved through the priority review and NOC/c pathways were analysed together as a single group. Kappa scores measure whether there is more or less agreement between different evaluations than would be expected by chance. Levels of agreement were graded in accordance with the recommendations of Landis and Koch where <0 indicates no agreement, 0–0.20 slight agreement, 0.21–0.40 fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 substantial agreement and 0.81–1.0 almost perfect agreement.9

Subgroup analyses

The number and percent of small molecule drugs and biologics approved through the standard, priority and NOC/c pathways were calculated and compared using the χ2 statistic. Similarly, the Kappa values were calculated separately for small molecule drugs and biologics.

All drugs were categorised using the second level of the WHO Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system.10 Drugs in three therapeutic groups—antineoplastic agents (L01), antivirals for systemic use (J05) and immunosuppressants (L04)—were chosen for subgroup analyses because they are primarily used for serious, life-threatening diseases and because there are sufficient numbers in each group to allow for statistical analyses. The number and percent of each subgroup that received an expedited review was calculated and the review status and therapeutic ratings were compared for each drug in each of the subgroups including ‘all other therapeutic groups’ and Kappa values were calculated for each subgroup. Distribution of approval pathways in the subgroups individually and for the three subgroups combined versus all other therapeutic groups was compared using the χ2 statistic. Calculations were done using Excel 2016 for Macintosh (Microsoft) and Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software).

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in any aspect of this study.

Ethics

No patients were involved in this study and only publicly available data were gathered. Therefore, ethics approval was not required.

Results

Review status

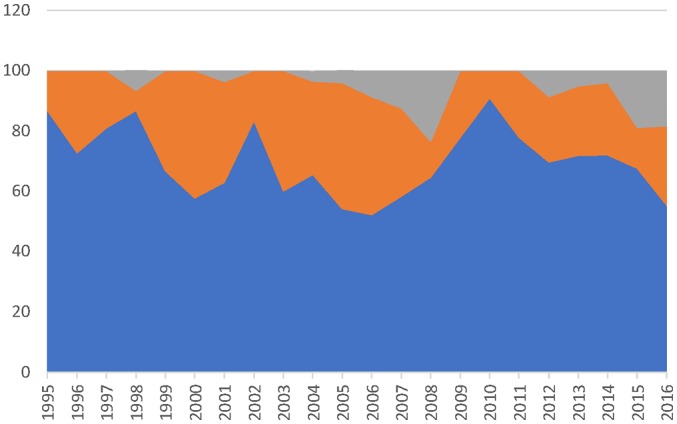

From 1 January 1995 to 31 December 2016, Health Canada approved a total of 623 NAS. Of these, 438 (70.3%) went through the standard pathway, 152 (24.4%) the priority pathway and 33 (5.3%) received a NOC/c. Almost 30% (29.7%) went through the expedited review pathways over the entire period, varying from a low of 9.1% in 2010 to a high of 47.8% in 2006 (table 2). (Health Canada used both a priority and NOC/c approval for 11 drugs, data not shown.) Visual inspection of figure 1 shows that there is no trend to using expedited review pathways more liberally or more conservatively over the time period (online supplementary tables 1 and 2, drugs with and without therapeutic evaluations, respectively, give all of the data extracted for the 623 drugs in question).

Table 2.

Review status of new active substances approved 1995–2016

| Year | Number of new active substances approved | Number (%) with standard review | Number (%) with priority review | Number (%) with NOC/c review | Number (%) with any expedited pathway review |

| 1995 | 30 | 26 (86.7) | 4 (13.3) | – | 4 (13.3) |

| 1996 | 33 | 24 (72.7) | 9 (27.3) | – | 9 (27.3) |

| 1997 | 42 | 34 (81.0) | 8 (19.0) | – | 8 (19.0) |

| 1998 | 30 | 26 (86.7) | 2 (6.7) | 2 (6.7) | 4 (13.3) |

| 1999 | 36 | 24 (66.7) | 12 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 12 (33.3) |

| 2000 | 26 | 15 (57.7) | 11 (42.3) | 0 (0) | 11 (42.3) |

| 2001 | 27 | 17 (63.0) | 9 (33.3) | 1 (3.7) | 10 (37.0) |

| 2002 | 24 | 20 (83.3) | 4 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 4 (16.7) |

| 2003 | 20 | 12 (60.0) | 8 (40.0) | 0 (0) | 8 (40.0) |

| 2004 | 29 | 19 (65.5) | 9 (31.0) | 1 (3.4) | 10 (34.5) |

| 2005 | 24 | 13 (54.2) | 10 (41.7) | 1 (4.2) | 11 (45.8) |

| 2006 | 23 | 12 (52.2) | 9 (39.1) | 2 (8.7) | 11 (47.8) |

| 2007 | 24 | 14 (58.3) | 7 (29.2) | 3 (12.5) | 10 (41.7) |

| 2008 | 17 | 11 (64.7) | 2 (11.8) | 4 (23.5) | 6 (35.3) |

| 2009 | 27 | 21 (77.8) | 6 (22.2) | 0 (0) | 6 (22.2) |

| 2010 | 22 | 20 (90.9) | 2 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (9.1) |

| 2011 | 27 | 21 (77.8) | 6 (22.2) | 0 (0) | 6 (22.2) |

| 2012 | 23 | 16 (69.6) | 5 (21.7) | 2 (8.7) | 7 (30.4) |

| 2013 | 39 | 28 (71.8) | 9 (23.1) | 2 (5.1) | 11 (28.2) |

| 2014 | 25 | 18 (72.0) | 6 (24.0) | 1 (4.0) | 7 (28.0) |

| 2015 | 37 | 25 (67.6) | 5 (13.5) | 7 (18.9) | 12 (32.4) |

| 2016 | 38 | 21 (55.3) | 10 (26.3) | 7 (18.4) | 17 (44.7) |

| Total | 623 | 438 (70.3) | 152 (24.4) | 33 (5.3) | 185 (29.7) |

NOC/c, Notice of Compliance with conditions.

Figure 1.

Percent of drugs approved through different pathways. Grey—percent with Notice of Compliance with conditions; orange—percent with priority review; blue—percent with standard review.

There were 126 biologics approved versus 323 small molecules (data only available from 2000 onward). There was no difference in the distribution of the approval pathways (p=0.4867) (table 3). There were 81 approvals for antineoplastic agents, 47 for antivirals for systemic use, 36 for immunosuppressants and 365 for drugs in the remaining 68 categories (‘all other 68 therapeutic groups’) (online supplementary table 1). The distribution of approval pathways was significantly different for the three subgroups (p=0.0018) and for the three subgroups combined versus ‘all other therapeutic groups’ (p<0.00001) (table 3).

Table 3.

Subgroup comparison of review pathways

| Subgroup | Standard | Priority | Notice of Compliance with conditions | Total |

| Small molecules | 129 | 72 | 22 | 323 |

| Biologics | 73 | 45 | 8 | 126 |

| Antineoplastic agents | 34 | 26 | 21 | 81 |

| Antivirals for systemic use | 16 | 26 | 5 | 47 |

| Immunosuppressants | 22 | 13 | 1 | 36 |

| All other 68 therapeutic groups | 365 | 89 | 5 | 459 |

Small molecules vs biologics: Χ2=1.4402 (p=0.4867).

Antineoplastics vs antivirals vs immunosuppressants: Χ2=17.1978 (p=0.0018).

Antineoplastics+antivirals + immunosuppressants vs all other therapeutic groups: Χ2=97.4874 (p<0.00001).

bmjopen-2018-023605supp001.pdf (185.2KB, pdf)

Therapeutic value

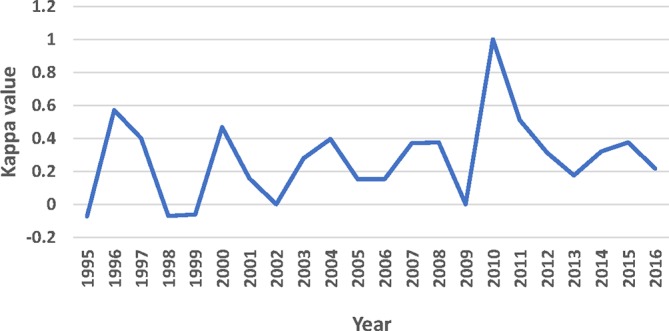

Out of the 623 NAS, 509 (81.7%) were evaluated for their therapeutic innovation either by the PMPRB and/or Prescrire. Health Canada used an expedited review pathway for 159 of the 509 drugs, whereas only 55 were judged to be therapeutically innovative by one or both of the independent reviews. Forty-two of the 55 drugs that were therapeutic innovations received an expedited review, 13 received a standard review and 117 (159 – 42) that were not therapeutic innovations also received an expedited review (table 4). The Kappa value for the entire period for all 509 drugs was 0.276 (95% CI 0.194 to 0.359) or fair. Figure 2 presents the Kappa values for each year which generally ranged from 0 (slight) to 0.4 (fair).

Table 4.

Number of new active substances with an expedited review and therapeutically innovative rating

| Year | Number (%) of NAS with a therapeutic assessment from Patented Medicine Prices Review Board and/or Prescrire | Number of NAS with an expedited review | Number of NAS rated as therapeutic innovation by either Patented Medicine Prices Review Board and/or Prescrire | Number of therapeutically innovative NAS with an expedited review |

| 1995 | 22 (73.3) | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| 1996 | 20 (60.6) | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| 1997 | 24 (57.1) | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| 1998 | 24 (80.0) | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| 1999 | 31 (86.1) | 10 | 1 | 0 |

| 2000 | 20 (76.9) | 9 | 4 | 4 |

| 2001 | 23 (85.2) | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| 2002 | 20 (83.3) | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 2003 | 19 (95.0) | 8 | 2 | 2 |

| 2004 | 26 (89.7) | 9 | 3 | 3 |

| 2005 | 21 (87.5) | 9 | 3 | 2 |

| 2006 | 21 (91.3) | 9 | 3 | 2 |

| 2007 | 22 (91.7) | 9 | 3 | 3 |

| 2008 | 15 (88.2) | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| 2009 | 26 (96.3) | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 2010 | 19 (86.4) | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 2011 | 23 (85.3) | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| 2012 | 21 (91.3) | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| 2013 | 36 (92.3) | 11 | 6 | 3 |

| 2014 | 22 (88.0) | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| 2015 | 30 (81.1) | 12 | 4 | 4 |

| 2016 | 24 (63.2) | 13 | 3 | 3 |

| 1995–2016 | 509 (81.7) | 159 | 55 | 42 |

NAS, new active substance.

Figure 2.

Agreement between review status and therapeutic value. Legend Kappa values: <0= no agreement; 0–0.20=slight agreement; 0.21–0.40=fair agreement; 0.41–0.60=moderate agreement; 0.61–0.80=substantial agreement; 0.81–1.0=almost perfect agreement.

There were 286 and 99 small molecule drugs and biologics, respectively, with therapeutic ratings. The Kappa values were 0.313 (95% CI 0.205 to 0.420) (fair) and 0.233 (95% CI 0.061 to 0.405) (fair), respectively. The overlapping 95% CIs indicate no difference in the Kappa values between the two groups (table 5).

Table 5.

Subgroup analyses: Kappa values

| Subgroup | Number (%) | Kappa value (95% CI) |

| Small molecule drugs | 286 | 0.313 (0.205 to 0.420) |

| Biologics | 99 | 0.233 (0.061 to 0.405) |

| Antineoplastic agents | 71 | 0.091 (0.017 to 0.200) |

| Antivirals for systemic use | 46 | 0.122 (0.011 to 0.233) |

| Immunosuppressants | 35 | 0.376 (0.075 to 0.675) |

| All other therapeutic groups | 357 | 0.385 (0.263 to 0.506) |

The 509 drugs were in 58 different second level ATC groups (drugs in 13 ATC groups did not have therapeutic evaluations): antineoplastic agents (71), antivirals for systemic use (46), immunosuppressants (35) and ‘all other therapeutic groups’ (357) (online supplementary table 1). Kappa values for the four groups were: 0.091 (95% CI 0.017 to 0.200) (slight), 0.200), 0.122 (95% CI 0.011 to 0.233) (slight)), 0.376 (95% CI 0.075 to 0.675) (fair) and 0.385 (95% CI 0.263 to 0.506) (fair), respectively. The 95% CIs for the Kappa values for the antineoplastic agents, antivirals for systemic use and immunosuppressants overlapped indicating no difference among the groups and the 95% CI for the immunosuppressants overlapped with the 95% CI for ‘all other therapeutic groups’. Drugs in the three therapeutic subgroups were much less likely to receive a standard review than were drugs in ‘all other therapeutic groups’, 43.7% vs 79.1% (data not shown).

Discussion

Almost 30% of the 623 new active substances that Health Canada reviewed between 1995 and 2016 went through at least one of two expedited review pathways—priority review or NOC/c, primarily a priority review. There is no difference between small molecule drugs and biologics in the approval pathways used indicating that for these two groups Health Canada does not see one or the other being more likely to offer significant new therapeutic benefits. However, the same is not true for the therapeutic subgroups. Drugs in the three specifically examined—antineoplastics, antivirals and immunosuppressants—were collectively more likely to be assigned to an expedited review pathway (56%) compared with drugs in ‘all other therapeutic groups’ (20.9%), possibly because of the nature of the diseases that they treat.

Just over 80% of the NAS approved had been assessed by the PMPRB and/or Prescrire for their therapeutic benefit. The Kappa value for the 509 drugs was 0.276 meaning that Health Canada’s ability to predict major therapeutic gain from these drugs was only fair. Furthermore, almost 25% (13/55) of the drugs that were therapeutic innovations did not receive an expedited review underscoring that Health Canada is not reliably able to predict which drugs will offer major therapeutic gains. The relatively low Kappa value may relate to when Health Canada makes its decision about what type of approval pathway to use. This assignment is at the start of the review process when all of the data will not have been fully assessed. In contrast, the PMPRB and Prescrire make their assessments after the drug has been marketed when more information about efficacy and safety is available.

As was the case with the assignment of an expedited review pathway, there is no difference in how accurately Health Canada predicts the therapeutic value of small molecule drugs and biologics as measured by Kappa values. The Kappa value for drugs in ‘all other therapeutic groups’ is higher than the value for drugs in the antineoplastic, antiviral and immunosuppressant groups. This difference may be because Health Canada is better able to predict that these drugs are less likely to be therapeutic innovations than drugs in the antineoplastic, antiviral and immunosuppressant groups. Out of the 357 drugs that had therapeutic evaluations in the ‘all other therapeutic groups’, 79.3% received a standard review compared with 43.7% of the 151 drugs in the three therapeutic subgroups.

How Health Canada uses its expedited review pathways is important for a number of reasons. First, their use may explicitly create an impression among clinicians and patients that these drugs are likely to deliver major new therapeutic benefits despite the fact that the likelihood that they will is only ‘fair’ as measured by the Kappa value. Second, the NOC/c pathway requires companies to commit to conducting post-market studies to validate the efficacy of the product, but many of these studies are delayed,6 7 leaving clinicians and patients uncertain about the value of these products. In at least one case, Health Canada did not suspend the sale of a drug and allowed it to stay on the market despite not fulfilling the conditions required under its NOC/c. In December 2003, Iressa (gefitinib) was approved as a third-line treatment for non-small cell lung cancer on the condition that the company submit a study showing that it improved survival.11 When the study results were submitted to Health Canada, they showed no survival benefit for gefitinib compared with placebo.12 Health Canada recognised that the conditions had not been fulfilled, but rather than removing gefitinib from the market, in February 2005 it elected to allow it to continue to be sold.11 In 2009, the drug was deemed to have met its conditions after a new study showed non-inferiority, that is, survival after taking it was no worse compared to another chemotherapeutic agent.13 Third, although the priority and standard approval pathways are equivalent in terms of the amount of data reviewed, the former is done in 180 days compared with 300 days for the latter, meaning that the priority pathway is more resource intensive possibly drawing resources from other Health Canada activities. Finally, drugs reviewed through both expedited review pathways are more likely to receive safety warnings once they are on the market compared with drugs with a standard approval.2 14

As figure 1 indicates, Health Canada is not using the expedited review pathways more liberally (or more conservatively) over time, but as figure 2 shows it has not improved its ability to predict therapeutic innovation over the 22 years evaluated in this study. The Introduction describes the criteria that Health Canada uses to assign a drug to either a priority review or a NOC/c review but how those criteria are applied and whether Health Canada periodically reviews its performance are not known.

Contrary to the situation in the USA where the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has been using an increasing number of expedited development or review programmes, Health Canada’s use of its programmes has been relatively stable since 1995. Between 1987 and 2014, 43% received a priority review from the FDA and 19% were approved through the fast track programme which approximately corresponds to a NOC/c.15 (Drugs could be associated with both programmes.) However, when it comes to approving oncology drugs through an expedited pathway, Health Canada is only marginally better than the FDA. In the USA, only 1 of 15 (6.7%) oncology drugs approved through an expedited programme from 1 January 2008, through 31 December 2012 had a proven survival benefit compared with the other 6 and 8 that either had no overall survival benefit or an unknown benefit, respectively.16 In this current study, out of 42 antineoplastic agents that Health Canada gave an expedited review, only 6 (14.3%) were rated as therapeutically innovative. The accelerated assessment (AA) process and the conditional approvals pathway used by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) are roughly the equivalent of Health Canada’s priority review and NOC/c pathway.17 The EMA used the former for 15.5% (23/148) of new drugs between 2012 and 2016,18 19 while the latter was used for 10.1% (30/296) of new drugs between 2006 and 2016.19 20 In the same time periods, Health Canada used a priority approval 21.6% (35/162) of the time time and its NOC/c pathway 9.1% (28/308) of the time.

Limitations

Almost 20% of new drugs approved by Health Canada were not evaluated for their therapeutic innovation by either the PMPRB or La revue Prescrire. The absence of these evaluations may have skewed the Kappa values in either a more positive or more negative direction. The lack of the availability of reports from Health Canada reviewers means that the reasons why drugs were assigned to a specific review pathway cannot be evaluated.

Conclusion

Health Canada continues to use expedited review pathways for about 30% of new drugs. Other regulatory authorities such as the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration and the EMA are in the process of either implementing or expanding expedited review pathways21–23 and should study the example of what has happened in Canada. The rationale for using expedited review pathways is to get important therapeutic advances to patients in a timely manner, but Health Canada’s ability to predict which of these drugs will fulfil this expectation has not improved over a 22-year period and remains relatively low. Moreover, use of these pathways comes with both health related and resource costs. The findings in this study should provoke a discussion about whether Health Canada should continue to use these pathways and if so how their use can be improved.

bmjopen-2018-023605supp002.pdf (69.4KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

None

Footnotes

Contributors: JL came up with the idea for this study, gathered and analysed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: In 2015–2017, Joel Lexchin received payment from two non-profit organisations for being a consultant on a project looking at indication-based prescribing and a second looking at which drugs should be distributed free of charge by general practitioners. In 2015, he received payment from a for-profit organisation for being on a panel that discussed expanding drug insurance in Canada. He is on the Foundation Board of Health Action International.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi: 10.5061/dryad.0bf6000.

References

- 1. Health Products and Food Branch. Access to therapeutic products: the regulatory process in Canada.. 2006. http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2007/hc-sc/H164-9-2006E.pdf

- 2. Lexchin J. Post-market safety warnings for drugs approved in Canada under the Notice of Compliance with conditions policy. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015;79:847–59. 10.1111/bcp.12552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Health Canada: Health Products and Food Branch. Guidance for industry: priority review of drug submissions. Ottawa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Health Canada. Notice of compliance with conditions (NOC/c). Ottawa, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lexchin J. Health Canada’s use of its priority review process for new drugs: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006816 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lexchin J. Notice of compliance with conditions: a policy in limbo. Healthc Policy 2007;2:114–22. doi:10.12927/hcpol.2007.18862 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Law MR. The characteristics and fulfillment of conditional prescription drug approvals in Canada. Health Policy 2014;116:154–61. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Prescrire Editorial Staff. Prescrire’s ratings system: gauge the usefulness of new products at aglance. Secondary Prescrire’s ratings system: gauge the usefulness of new products at a glance. 2011. http://english.prescrire.org/en/81/168/46800/0/NewsDetails.aspx

- 9. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Structure and principles.. 2011. http://www.whocc.no/atc/structure_and_principles/

- 11. Health Canada. Clarification from Health Canada regarding the status of Iressa® (gefitinib) in Canada.. 2005. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/prodpharma/activit/fs-fi/fact_iressa-eng.php

- 12. Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, et al. Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer). Lancet 2005;366:1527–37. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim ES, Hirsh V, Mok T, et al. Gefitinib versus docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (INTEREST): a randomised phase III trial. Lancet 2008;372:1809–18. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61758-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lexchin J. New drugs and safety: what happened to new active substances approved in Canada between 1995 and 2010? Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1680–1. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.4444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kesselheim AS, Wang B, Franklin JM, et al. Trends in utilization of FDA expedited drug development and approval programs, 1987-2014: cohort study. BMJ 2015;351:h4633 10.1136/bmj.h4633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim C, Prasad V. Cancer drugs approved on the basis of a surrogate end point and subsequent overall survival: an analysis of 5 years of US food and drug administration approvals. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1992–4. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baird LG, Banken R, Eichler HG, et al. Accelerated access to innovative medicines for patients in need. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2014;96:559–71. 10.1038/clpt.2014.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. European Medicines Agency. Accelerated assessment (AA): review of 10 months experience with the new AA process.. 2018. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Presentation/2018/01/WC500241575.pdf

- 19. Centre for Innovation in Regulatory Science. New drug approvals in six major authorities 2007-2016: focus on the internationalisation of medicines. London, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20. European Medicines Agency. Conditional marketing authorisation: report on ten years of experience at the European Medicines Agency. London, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21. European Medicines Agency. Final report on the adaptive pathways pilot. London, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Department of Health, Therapeutic Goods Administration. Consultation: provisional approval pathway for prescription medicines. Proposed registration process and post-market requirements. Woden, ACT, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Department of Health, Therapeutic Goods Administration. Consultation: expedited pathways for prescription medicines. Eligibility criteria and designation process. Woden, ACT, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lexchin J. Postmarket safety in Canada: are significant therapeutic advances and biologics less safe than other drugs? A cohort study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004289 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023605supp001.pdf (185.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-023605supp002.pdf (69.4KB, pdf)