Abstract

Objectives

Up-to-date information on the patterns of acute poisoning is crucial for the proper management of poisoning events. The objectives of this study were to analyse the characteristics of patients suffering from acute poisoning admitted to the emergency department (ED) in a tertiary medical centre in Northeast China and to compare these characteristics with those of a previous comparable study.

Design

Retrospective and descriptive study.

Setting

Data were collected from the hospital information system in Shengjing Hospital, China, from January 2012 to December 2016.

Participants

All cases aged ≥11 years old with a diagnosis of acute poisoning.

Results

In total, 5009 patients aged ≥11 years presented to the ED with acute poisoning during the study period. The average age of the patients was 36.0±15.1 years and over half (52.7%) were in the 20–39age group. The female to male ratio was 1.2:1. Patients with acute poisoning mainly lived in rural areas rather than in urban areas. The majority of patients consumed poison as suicide attempts (56.7%). Men were more commonly poisoned by drug abuse than women, but women outnumbered men in suicidal poisoning. The most common form of poison intake was ingestion (oral intake; 86.2%). The five most common toxic agent groups, in descending order, were therapeutic drugs (32.6%), pesticides (26.9%), alcohol (20.7%), fumes/gases/vapours (11.4%) and chemicals (3.6%). Sedatives/hypnotics in the therapeutic drugs group and paraquat in the pesticides group were the most common toxic agents, respectively. The mortality rate of study participants was 1.3%, with 64 deaths.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate the need to strengthen education on the rational and safe use of drugs in Shenyang.

Keywords: poisoning, carbon monoxide poisoning, pesticides, paraquat, suicide

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The cross-sectional and retrospective study design included over 5000 poisoning cases in five consecutive years.

Although the sample size in this study was large, its retrospective nature made it difficult to obtain complete information on all poisoning cases, which may have introduced bias.

Data from a single centre teaching hospital, even with three branches, may not reflect the precise situation in this region.

Introduction

Acute poisoning is defined as an acute exposure (less than 24 hours) to a toxic substance.1 Acute poisoning is a major public and preventable health issue contributing to morbidity and mortality in many parts of the world. It is estimated that poisoning events are responsible for more than one million illnesses annually.2 3 Low mortality contrasts with high morbidity in acute poisoning; however, patients who attempt suicide usually have higher mortality.4–6 As the most common form of fatal self-harm in rural Asia, poisoning accounts for more than 60% of deaths.7

China is a developing country transitioning from an agricultural to an industrialised economy. In recent years, the number of acute poisoning cases in China has continued to increase,8 and both poisoning and injury are now two of the top five causes of death.9 Of the various types of poisoning, pesticide poisoning is the most common in most regions of China, while therapeutic drugs poisoning is the main type of poisoning in developed regions or cities, such as Shanghai.9–13 Shenyang is the provincial capital of Liaoning and the biggest city in Northeast China, with an estimated population of more than 8.1 million.14 Liaoning is an industrial province, but agriculture is still an important economic sector. The widespread use of pesticides, such as organophosphorus compounds, by farmers may increase the risk of poisoning events in this area.15 A previous investigation performed by Zhao et al 16 in this region from 1997 to 2007 showed that (1) medicine was the most common poisoning agent (41.4%), followed by pesticides (15.2%), alcohol (14.1%), carbon monoxide (CO) (12.5%) and food (9.7%); (2) the major medicines were sedatives/hypnotics and the major pesticides were organophosphates; and (3) mortality decreased from 2.1% to 0.4% over the 10-year study period, with an average mortality rate of 1.0%.

In the last few decades, China has witnessed significant advancements in the fields of agriculture, industrial technologies and medical pharmacology. These advancements have been paralleled by marked changes in the trends of acute poisoning,17 and have led to the development and easy accessibility of a vast number of toxic agents including pesticides, therapeutic drugs and other chemicals. Thus, the toxic agents associated with morbidity and mortality and the pattern of acute poisoning, which vary from place to place and over time, are expected to change. Therefore, there is a constant need to obtain up-to-date information on acute poisoning for planning rational use of resources and for evaluating public health interventions. The aims of this retrospective and descriptive study were to describe the clinical and sociodemographic patterns of acute poisoning in the emergency department (ED) of Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, a tertiary care centre, and to compare these patterns with previous findings obtained by Zhao et al.16

Methods

This retrospective and descriptive study based on hospital records was carried out in Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University in Shenyang, China. Shengjing Hospital is a regional tertiary care hospital in Northeast China with three hospital areas and covers the entire Liaoning province and some areas of neighbouring provinces. Moreover, the Liaoning Poisoning Diagnosis and Treatment Center was established in the ED of Shengjing Hospital in July 2011, and the ED has a specialised toxicology unit. Hence many patients with poisoning who seek treatment visit or are referred to this hospital. We reviewed all records of cases of poisoning admitted to the ED (including cases referred to the ED from other wards) over five consecutive years from January 2012 to December 2016. Patients admitted to the ED with a diagnosis of drug poisoning and aged ≥11 years were enrolled in this study. Diagnoses were established by patients’ history, physical examination, and routine and toxicological laboratory evaluations. Poisoned patients <11 years admitted to the paediatric ward and those with animal bites (snake, insect) due to infrequency and chronic poisoning were excluded from the study.

Relevant medical records were obtained from the electronic hospital information system (HIS). The HIS is an electronic system used in the clinic to record patient information. Poisoning cases were retrieved by searching the HIS using the following keywords: poisoning, alcohol, CO and organophosphate. Demographic data including age, gender, place of residence, diagnosis, type of exposure (suicidal, abusive, accidental and unknown), type of toxic agent (the common name or trade name were indicated, where available), duration of hospital stay and the outcome of treatment (whether the patient survived or died) were collected and documented on a structured form. The circumstances of poisoning were deduced from the patient’s history.

Toxic agents were classified as therapeutic drugs, pesticides, alcohol, poisonous fumes/gases/vapours, chemicals, food, other substances and unknown. The subgroup of toxic agents was categorised based on the indications for use. Mixed drugs were defined as the ingestion of two or more drugs. The toxic agent was categorised as unknown when no suspected toxic agent was reported in the patient’s history.

The type of exposure was classified as suicidal, abusive, accidental and unknown as follows: (1) Exposure due to the inappropriate use of drugs for self-destruction was categorised as suicidal. (2) Exposure due to the intentional improper or incorrect use of a drug in which the victim was likely attempting to achieve a euphoric or psychotropic effect was categorised as abusive. (3) Accidental was classified as environmental poisoning, misuse, food poisoning and an adverse reaction: (a) if patients were poisoned due to being in an environment where a toxic substance (eg, CO) was present, this was categorised as environmental poisoning; (b) an overdose of medicine or being given the wrong drug, taking the wrong drug in error or taking a drug inadvertently were categorised as misuse; (c) exposure due to the ingestion of edible items was categorised as food poisoning; and (d) side effects from a herb or health product was categorised as an adverse reaction. (4) If information was unavailable, the cause of poisoning was categorised as unknown.

Gastric lavage, activated charcoal, intubation, infusion and dieresis therapy, and haemoperfusion were standard treatment protocols for poisoning caused by ingestion. Haemodialysis was performed when indicated. Special antidotes, naloxone for alcohol poisoning, and vitamin K1 and acetamide for rodenticide poisoning were given as indicated. For poisoning with no specific available antidotes, symptomatic treatment was administered.

Patients with normal symptoms, signs and laboratory findings on discharge were categorised as recovery. Patients with normal symptoms and signs but abnormal or unavailable laboratory findings on discharge were categorised as relative recovery.

Microsoft Excel 2007 was used to perform descriptive statistical analyses of the data. The average age was presented as mean±SD. To evaluate the differences, χ2 test was performed using SPSS V.21.0 for Windows. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved.

Results

A total of 5375 cases of poisoning (age ≥11 years of age) from 829 808 entries were obtained from the HIS from 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2016. Of these, 366 were identified as animal bites (10 cases) and chronic poisoning events, leaving a total of 5009 unique cases that met our criteria. These cases comprised 0.6% of all emergency admissions. Descriptive information, including age, gender, type and route of exposure, place of residence, length of hospital stay, and outcome of the poisoned patients, is summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of poisoned patients admitted to the emergency department from 2012 to 2016

| Variables categories | n | % |

| Age group | ||

| 11–19 | 557 | 11.1 |

| 20–29 | 1547 | 30.9 |

| 30–39 | 1094 | 21.8 |

| 40–49 | 817 | 16.3 |

| 50–59 | 575 | 11.5 |

| 60–69 | 267 | 5.3 |

| ≥70 | 152 | 3.0 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 2296 | 45.8 |

| Female | 2713 | 54.2 |

| Type for exposure | ||

| Suicidal | 2842 | 56.7 |

| Abusive | 1105 | 22.1 |

| Accidental | 1017 | 20.3 |

| Unknown | 45 | 0.9 |

| Route of exposure | ||

| Ingestion (oral) | 4316 | 86.1 |

| Inhalation (nasal) | 590 | 11.8 |

| Contact (dermal) | 98 | 2.0 |

| Other | 5 | 0.1 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | 2415 | 48.2 |

| Rural | 2568 | 51.3 |

| Unknown | 26 | 0.5 |

| Length of hospital stay | ||

| <48 hours | 367 | 7.3 |

| <1 week | 3219 | 64.3 |

| >1 week | 1423 | 28.4 |

| Outcome | ||

| Recovery | 1416 | 28.3 |

| Relative recovery | 3255 | 65.0 |

| Referral to other centres | 198 | 3.9 |

| Left against medical advice | 76 | 1.5 |

| Death | 64 | 1.3 |

| Total | 5009 | 100.0 |

Age and gender

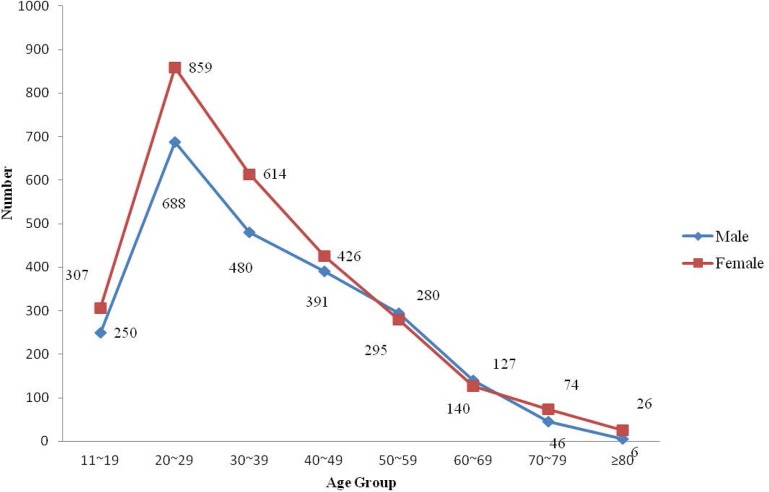

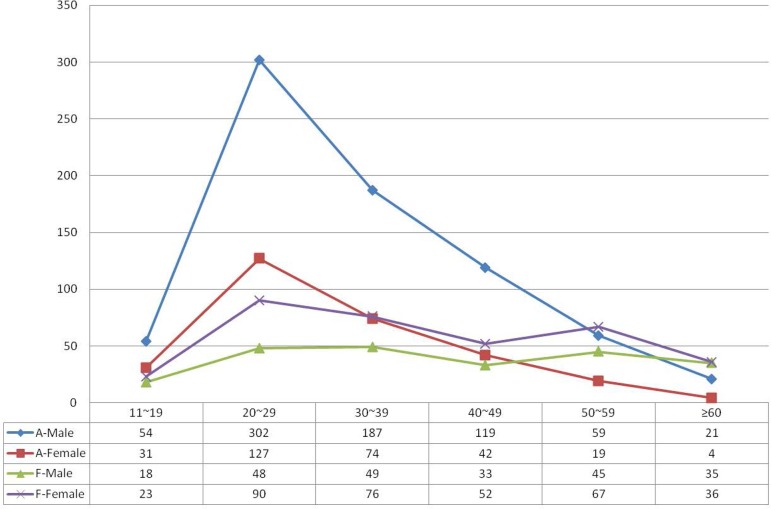

Of the 5009 cases included, 2713 (54.2%) were female and 2296 (45.8%) were male, and the male to female ratio was 1:1.2. In this study, the youngest patient was 11 years old, while the oldest patient was 92 years old. The mean age of all patients was 36.0±15.1 years. The mean age of male and female patients was 36.4±15.0 years and 35.7±15.3 years, respectively. The patients most vulnerable to poisoning were those aged 20–29 years (30.9% of cases), followed by patients aged 30–39 years (21.8% of cases) and 40–49 years (16.3% of cases) (figure 1). There was a statistically significant gender difference (male and female) between the different age groups of poisoned patients (χ2=28.19, p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Distribution of all poisoning cases by age and gender.

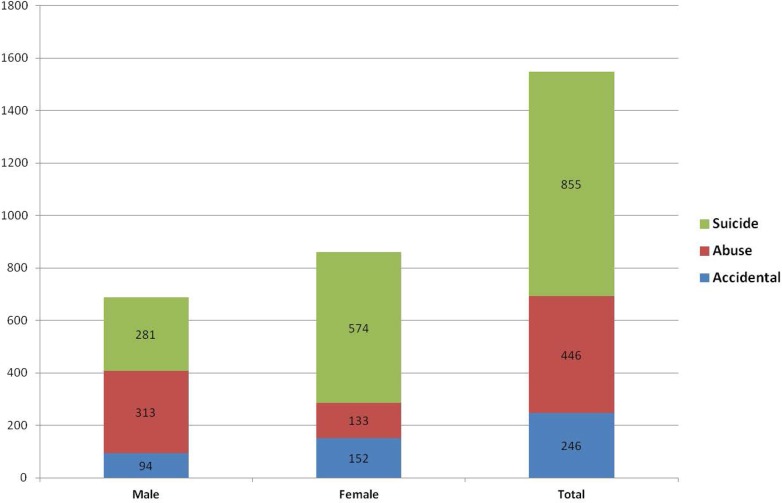

The predominant group of toxic agents consumed by the 20–29 age group was therapeutic drugs (37.4%, 579 cases) (table 2). Of these, sedatives/hypnotics (169 cases) plus analgesics (120 cases) accounted for over half. Alcohol and pesticides were ranked second and third, accounting for 27.7% and 19.6%, respectively. There was a statistically significant gender difference related to suicide and drug abuse in the 20–29 age group (χ2=140.29, χ2=167.69, p<0.001). Most cases of intentional poisoning were seen in young adults (those aged 20–29 years old), with 855 suicide attempts and 446 abuse cases (figure 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of toxic agents consumed by the 20–29 age group from 2012 to 2016

| Toxic agents category | n | Group percentage | Total percentage | Direct percentage* |

| Therapeutic drugs | 579 | 100.0 | 37.4 | 35.4 |

| Sedatives and hypnotics | 169 | 29.2 | 10.9 | 35.9 |

| Analgesics | 120 | 20.7 | 7.7 | 44.3 |

| Mixed drugs | 92 | 15.9 | 5.9 | 34.2 |

| Cold and cough preparations | 64 | 11.1 | 4.1 | 39.3 |

| Antipsychotics | 35 | 6.0 | 2.3 | 28.0 |

| Cardiovascular drugs | 22 | 3.8 | 1.4 | 19.6 |

| Other drugs | 29 | 5.0 | 1.9 | 30.2 |

| Antimicrobials | 27 | 4.7 | 1.7 | 41.5 |

| Traditional Chinese medicine | 21 | 3.6 | 1.4 | 32.8 |

| Alcohol | 429 | 27.7 | 41.3 | |

| Pesticides | 304 | 100.0 | 19.6 | 22.5 |

| Paraquat | 133 | 43.8 | 8.6 | 20.7 |

| Rodenticide | 66 | 21.7 | 4.3 | 25.5 |

| Organophosphate | 45 | 14.8 | 2.9 | 19.4 |

| Other | 48 | 15.8 | 3.1 | 30.0 |

| Unknown | 12 | 3.9 | 0.8 | 22.2 |

| Fumes/gases/vapours | 138 | 8.9 | 24.1 | |

| Chemicals | 33 | 2.1 | 18.2 | |

| Food | 16 | 1.0 | 18.2 | |

| Other substance | 16 | 1.0 | 47.1 | |

| Unknown | 35 | 2.3 | 34.3 | |

| Total | 1550† | 100.0 | 30.9 |

*The ratio of the same toxic agent consumed by people in their 20s to people of all age groups.

†Among the 1550 cases, 3 cases were calculated tautologically for a combination of alcohol poisoning and other drugs poisoning.

Figure 2.

Intention for the 20–29 age group cases from 2012 to 2016.

Type of exposure

Table 3 lists the reasons for toxin exposure in these patients. It was noted that suicidal exposure occurred in the overwhelming majority of poisonings (2842, 56.7%), followed by abusive exposure (1105, 22.1%), accidental exposure (1017, 20.3%) and unknown reason (45, 0.9%). There was a significant gender difference in suicide and drug abuse: women were involved in more suicidal poisonings than men: 63.4% for female vs 36.6% for male (χ2=226.09, p<0.001); and poisoning due to drug abuse showed the opposite tendency: 70.8% for male vs 29.2% for female (χ2=354.97, p<0.001). The main substances used were therapeutic drugs and pesticides for suicide attempts and alcohol for abuse. CO poisoning (~80% of cases) was the most common environmental poison, and pesticides poisoning (20%) was less common. Therapeutic drugs were taken mistakenly or in overdose by women.

Table 3.

Type of exposure of all cases by gender

| Type for exposure | Male | Female | Total | χ2 test | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | P values | |

| Suicidal | 1040 | 45.3 | 1802 | 66.4 | 2842 | 56.7 | 226.086 | 0.000 |

| Abusive | 782 | 34.1 | 323 | 11.9 | 1105 | 22.1 | 354.968 | 0.000 |

| Accidental | 451 | 19.6 | 566 | 20.9 | 1017 | 20.3 | 1.143 | 0.285 |

| Environmental | 303 | 13.2 | 387 | 14.3 | 690 | 13.8 | 1.622 | 0.203 |

| Misuse | 97 | 4.2 | 106 | 3.9 | 203 | 4.1 | 0.323 | 0.570 |

| Food poisoning | 35 | 1.5 | 53 | 2.0 | 88 | 1.8 | 1.327 | 0.249 |

| Adverse reaction | 16 | 0.7 | 20 | 0.7 | 36 | 0.7 | 0.028 | 0.866 |

| Unknown | 23 | 1.0 | 22 | 0.8 | 45 | 0.9 | 0.509 | 0.476 |

| Subtotal | 2296 | 100.0 | 2713 | 100.0 | 5009 | 100.0 | ||

χ2, Chi-square; Significance of p values are in bold.

Routes of exposure

Among the various routes of exposure, ingestion was the most common (86.2%), followed by inhalation (11.8%) and contact (2.0%).

Common substances in human exposures

The most prevalent substance categories are shown in table 4 and are listed by frequency of exposure in the study patients. This ranking shows the direction in which prevention efforts should be focused, as well as the types of poisonings our hospital regularly manages. The four most common toxic agent groups, in decreasing order, were therapeutic drugs, pesticides, alcohol and fumes/gases/vapours; 676 (13.5%) patients consumed two or more toxic agents. However, with regard to specific substances, alcohol, paraquat, CO and sedatives/hypnotics were the four main toxic agents.

Table 4.

Distribution of toxic agent over 5 years

| Toxic agent category | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Total | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | Total (%) | |

| Therapeutic drugs | 303 | 100.0 | 394 | 100.0 | 326 | 100.0 | 310 | 100.0 | 304 | 100.0 | 1637 | 100.0 | 32.6 |

| Sedatives and hypnotics | 101 | 33.3 | 141 | 35.8 | 79 | 24.2 | 68 | 21.9 | 82 | 27.0 | 471 | 28.8 | 9.4 |

| Analgesics | 50 | 16.5 | 67 | 17.0 | 62 | 19.0 | 53 | 17.1 | 39 | 12.8 | 271* | 16.6 | 5.4 |

| Mixed drugs | 42 | 13.9 | 63 | 16.0 | 53 | 16.3 | 52 | 16.8 | 59 | 19.4 | 269 | 16.4 | 5.4 |

| Cold and cough medicines | 31 | 10.2 | 26 | 6.6 | 37 | 11.4 | 42 | 13.6 | 27 | 8.9 | 163 | 10.0 | 3.2 |

| Psychotropics | 16 | 5.3 | 23 | 5.8 | 23 | 7.1 | 27 | 8.7 | 36 | 11.8 | 125 | 7.6 | 2.5 |

| Cardiovascular drugs | 15 | 5.0 | 27 | 6.9 | 22 | 6.8 | 26 | 8.4 | 22 | 7.2 | 112 | 6.8 | 2.2 |

| Other drugs | 16 | 5.3 | 21 | 5.3 | 24 | 7.4 | 20 | 6.5 | 15 | 4.9 | 96 | 5.9 | 1.9 |

| Antimicrobials | 19 | 6.3 | 12 | 3.1 | 15 | 4.6 | 8 | 2.6 | 11 | 3.6 | 65 | 4.0 | 1.3 |

| Traditional Chinese medicine | 13 | 4.3 | 14 | 3.6 | 11 | 3.4 | 14 | 4.5 | 13 | 4.3 | 65 | 4.0 | 1.3 |

| Pesticides | 241 | 100.0 | 280 | 100.0 | 308 | 100.0 | 272 | 100.0 | 248 | 100.0 | 1349 | 100.0 | 26.9 |

| Paraquat | 97 | 40.2 | 134 | 47.9 | 149 | 48.4 | 141 | 51.8 | 123 | 49.6 | 644 | 47.7 | 12.8 |

| Rodenticide | 50 | 20.7 | 55 | 19.6 | 60 | 19.5 | 49 | 18.0 | 45 | 18.2 | 259 | 19.2 | 5.2 |

| Organophosphate | 56 | 23.2 | 44 | 15.7 | 48 | 15.6 | 46 | 16.9 | 38 | 15.3 | 232 | 17.2 | 4.6 |

| Other | 24 | 10.0 | 33 | 11.8 | 42 | 13.6 | 28 | 10.3 | 33 | 13.3 | 160 | 11.9 | 3.2 |

| Unknown | 14 | 5.8 | 14 | 5.0 | 9 | 2.9 | 8 | 2.9 | 9 | 3.6 | 54 | 4.0 | 1.1 |

| Alcohol | 203 | 227 | 226 | 182 | 201 | 1039 | 20.7 | ||||||

| Fumes/gases/vapours | 70 | 144 | 103 | 119 | 136 | 572 | 11.4 | ||||||

| Chemicals | 25 | 47 | 46 | 32 | 31 | 181 | 3.6 | ||||||

| Food | 20 | 9 | 15 | 35 | 9 | 88 | 1.8 | ||||||

| Other substance | 8 | 11 | 7 | 10 | 14 | 50 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Unknown | 22 | 24 | 17 | 19 | 20 | 102 | 2.0 | ||||||

| Subtotal | 892 | 1136 | 1048 | 979 | 963 | 5018† | 100.0 | ||||||

*Including 13 cases of opioids poisoning.

†Nine cases were calculated tautologically, of which seven cases had a combination of alcohol poisoning and other drugs poisoning, and two cases had a combination of carbon monoxide poisoning and other drugs poisoning.

Therapeutic drug categories

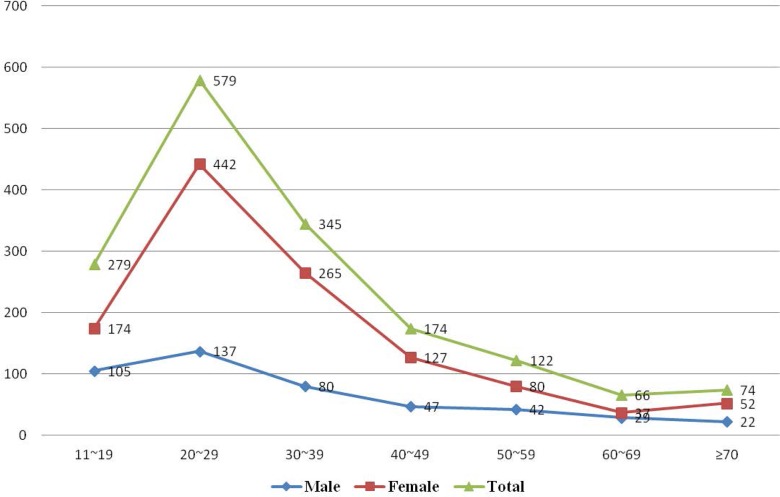

Therapeutic drug poisoning showed a slight decrease during the 5-year study despite a high number in 2013. A total of 1637 cases involved therapeutic drug poisoning. Of these cases, 28.8% involved sedatives/hypnotics poisoning, which were the most commonly used drugs, followed by analgesics (16.6%) (including 13 cases of opioids poisoning) and cold and cough medicines (10.0%). Mixed drug poisoning was found in approximately 16.4% of patients. The rate of psychotropics poisoning increased over the 5-year period. Cardiovascular drugs, antimicrobials, traditional medicine and other drugs showed a relatively stable trend. Drug poisoning was more common in both men and women aged 20–29 years attempting suicide (figure 3). However, drug poisoning was significantly more frequent in women than in men (71.9% vs 28.1%).

Figure 3.

Distribution of therapeutic drugs poisoning by age and gender.

Pesticide categories

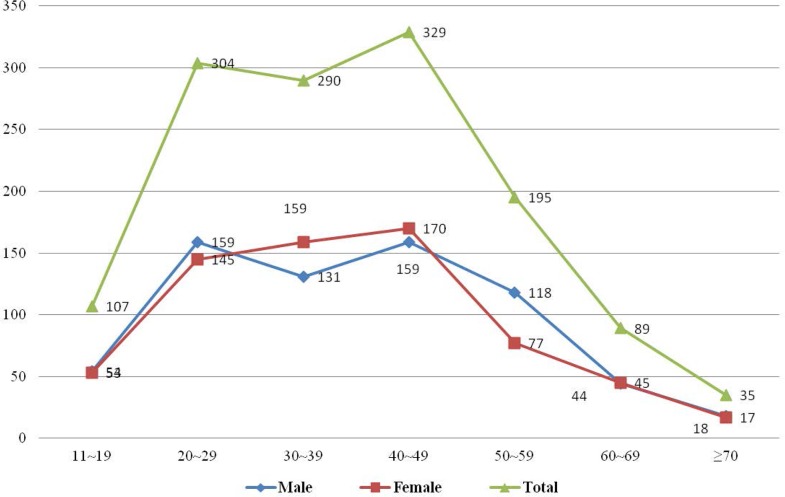

Pesticide poisoning showed an increasing trend from 2012 to 2015 but decreased in 2016. A total of 1349 cases were observed to have pesticide poisoning. Of these cases, the predominant pesticide poison taken was paraquat (47.7% of cases), followed by rodenticide (19.2%), organophosphate (17.2%) and other pesticides (11.9%). A slightly higher number of men (683 cases) than women (666 cases) had pesticide poisoning. With regard to the distribution of age and gender in pesticide poisoning, there were two peaks, one in the 20–29 age group and the other in the 40–49 age group for both men and women (figure 4). Eighty-eight per cent of pesticide poisonings were suicide attempts, and men were involved in 5% more accidental pesticide poisonings than women. Pesticide poisoning was most frequent during the month of July.

Figure 4.

Distribution of pesticide poisoning by age and gender.

Alcohol and fumes/gases/vapours

There was a stable trend in alcohol poisoning. Alcohol poisoning was predominant in men and was ~2.5 times higher in men than in women. Alcohol poisoning was more prevalent in the 20–29 age group than in any other age group (figure 5). In addition, <1% of alcohol poisoning cases were found to be affected by other poisonings. Fumes/gases/vapours poisoning displayed an increasing trend, even though there was a decrease from 2013 to 2014. Of these cases, CO was the dominant toxic agent. CO poisoning was more common in the 20–39 age group and in women. The majority of CO poisoning events occurred in winter.

Figure 5.

Distribution of alcohol and fumes poisoning by age and gender. A-Male means alcohol poisoning for male; A-Female means alcohol poisoning for female; F-Male means fumes/gas/fog poisoning for male; and F-Female means fumes/gas/fog poisoning for female.

Treatment and outcome

It was noted that gastric lavage and activated charcoal were administered in 72.5% (n=3634) and 64.8% (n=3244) of cases, respectively, to prevent absorption of toxic agents. Some 7.7% of cases (n=385) received haemodialysis treatment. All patients with organophosphorus poisoning (n=232) were treated with atropine and pralidoxime. In addition, hyperbaric oxygen therapy for CO poisoning was performed in all cases (n=556).

A total of 4945 patients were discharged from the hospital, including 1416 cases with complete recovery, 3255 cases with relative recovery, 347 cases referred to another institution and 253 cases who left the hospital during treatment. The hospital mortality rate was 1.3%, with 64 deaths, including 36 women and 28 men. The fatality ratio was 1.3% for female patients and 1.2% for male patients. More than half of the fatality cases (n=33) occurred in the 40–59 age group. Sixty-eight per cent of the patients who died lived in urban areas. Death was due to suicide attempt in 51 cases, accidental poisoning in 11 cases, and in 2 cases the type of poisoning was unknown. The associated agents involved in death were paraquat (33 cases), therapeutic drugs (16 cases), organophosphate (6 cases), food poisoning (4 cases), CO (2 cases), alcohol (1 case) and unidentified poisons (2 cases).

Comparison with previous findings by Zhao et al

The female to male ratio was 1.5:1 in Zhao et al’s study and 1.2:1 in the present study. Similar to Zhao et al’s report, the most vulnerable patients were aged 20–29 years, but the percentage in Zhao et al’s study was 37.1%, which was higher than in our study. The major route of exposure was ingestion in both studies (86.2% in our study and 81.8% in the previous study). With regard to the type of exposure, suicide attempt accounted for 69.6% and accidental exposure accounted for 29.7% in the previous study, higher than our findings. The most common toxic agents were the same in both studies, therapeutic drugs, followed by pesticides, alcohol and CO (41.4%, 15.2%, 14.1% and 12.5% in the previous study, and 32.6%, 26.9%, 20.7% and 11.4% in the present study). The major medicines were sedatives/hypnotics (27.5%) and the major pesticides were organophosphates (8.0%) in the previous study, while in this study the major toxic agents were sedatives/hypnotics (9.4%) and the major pesticide was paraquat (12.8%). The average mortality rate was 1.0% and 1.3% in the previous study and this study, respectively.

Discussion

Acute poisoning is one of the most frequent causes of visits to the ED and is a threat to public health. The annual rate of ED visits associated with poisoning varies widely across the world, and ranges from 0.1% to 0.7%.18 19 Studies in Western countries have reported annual rates of ED visits associated with poisoning of approximately 0.3%.19 20 In the present study, this rate was 0.6%, and a similar percentage (0.6%) was seen in the research carried out by Ergun.21 As it is not common practice for many poisoned patients to seek medical help in healthcare institutions, the annual rate of ED visits associated with poisoning recorded by hospitals may be misleading. Therefore, the actual number of poisoning cases may be more than that recorded, and accurate statistical data for poisonings are difficult to estimate. Developed countries also have similar problems in obtaining meaningful poisoning statistics even though they are equipped with advanced systems to collect population health data.22

This study concluded that the incidence of poisoning in women was slightly higher than that in men, especially among young adults aged 20–29 years, with a female to male ratio of 1.2:1. Similar findings have also been reported in Beijing, China (1.2:1)23 and Sari, Iran (1.2:1)17. In contrast, male preponderance has been found in some other countries.24 25

The results of this study showed a difference in poisoning based on age and indicated that the most affected age group was the 20–29 group (30.8%), with a secondary peak in the 30–39 age group (21.9%). Both intentional and accidental poisonings were common in men and women aged 20–29 years, which is consistent with previous findings in China16 23 and in other countries.26–28 The fact that poisoning is more common among young adults reflects their vulnerability to stress, possibly due to failure or frustration in relationships or exams, maladjustment and inability to cope with the high expectation of parents.29 30 Overall, this group of people is not emotionally stable or mature enough to tolerate extreme mental or physical pressure.31 32

Intentional poisoning (suicide+abuse) was the predominant cause of poisoning (78.8%) in the current study, an observation that is consistent with that in other studies.27 33 Our study indicated that of all poisoning cases, a large proportion were suicidal in nature, but the incidence was lower compared with Zhao et al’s study. This change may be related to the benefits of socioeconomic achievement and prosperity, such as higher employment and more educational opportunities, which may have contributed to the reduction in suicide rates in China.34 Despite this decline in suicide rate, suicide attempt is still the primary reason for poisoning due to the general belief that poisons terminate life with minimal suffering.35 36

Our study demonstrates that therapeutic drugs are the most frequently used toxic agents. A similar pattern of therapeutic drugs as the most common cause of acute poisoning has been observed in developed and some developing countries.37–42 With regard to the subgroup of therapeutic drugs in poisoning cases, sedatives/hypnotics were common in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Iran and Finland, while analgesics were the most frequently ingested drugs in Turkey and the USA. Pharmaceutical poisoning comprised 32.6% of the various drug poisonings observed in the present study, of which sedatives/hypnotics (28.8%) were the most frequently ingested agents. A similar pattern was also seen in Zhao et al’s study, although an apparent decline in sedatives/hypnotics poisoning was seen in our study.16 This decline may be connected with the implementation of drug classification control, where patients can only access these drugs with a doctor’s prescription.43 However, a rise was observed in the use of analgesics, cold and cough medicines, mixed drugs, as well as cardiovascular drugs, resulting in a different pattern from that seen previously. This may be explained by the easy availability of pharmaceuticals due to the numerous drugstores in China, inadequate governmental supervision, insufficient knowledge about rational use of analgesics,44 increase in the incidence of cardiovascular disease,45 and poor psychological well-being and mental fragility among populations.46 In addition, we found that the frequency of psychotropic drugs poisoning has increased, which indicates that mental disorder plays a part in poisoning events and should receive attention. It is noteworthy that the number of opioid poisonings is surprisingly small in our study, and this is associated with the government’s strict regulation on opioids and insufficient knowledge on opioids among physicians and patients (such as excessive worry about addiction and adverse events), making the use of opioids rare.47 48

Pesticide poisoning has occurred relatively frequently for some time, as shown by previously published papers from different countries.33 36 The incidence of this type of poisoning varies geographically and historically.49 Several studies conducted in India, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh showed a pesticide-dominant poisoning pattern, with organophosphates being the most common pesticide.50–52 Pesticides were the second leading cause of acute poisoning in this study, accounting for 26.6% of all poisoning cases, and showed an increased trend.16 There are two reasons for this increased frequency: first, suicide by pesticide poisoning is still high in China, although suicides related to pesticide poisoning in China have continuously declined from 2006 to 2013.53 Previous studies have shown that highly lethal pesticides are commonly used in suicide in rural China.54 55 Our study showed that up to 88% of pesticide poisonings were suicide attempts. Second, pesticides are used extensively and unsafely in agriculture and industry, and can be stored in the home, causing toxicity due to intentional and accidental exposures.55 The quantity of pesticide use is large and ever-increasing and has grown from 1.3 million ton in 2001 to 1.8 million ton in 2014.56 In the present study, paraquat was the most frequently used pesticide, and a similar pattern was found in a study carried out in Northeast China, which showed an increasing trend,57 whereas a decreasing trend was found in Korea.58

Not surprisingly, our study found that alcohol poisoning was common and accounted for 20.7% of all poisoning cases. The incidence of alcohol poisoning increased compared with previous figures in Zhao et al’s study (14.1%). This change can be explained by rapid social and economic development, urbanisation, and increased alcohol production and alcoholic beverage commercials in the mass media, which have all led to an increase in alcohol consumption.59 According to recent data, the annual per-capita alcohol consumption in Chinese adults in 2012 was 3 L.60 Findings reported elsewhere in China showed a higher number of alcohol poisonings.61 Alcohol poisoning in other countries has been shown to be lower.38 62–64 This discrepancy is partially related to the disparity in alcohol consumption habits between different countries and districts. In Chinese culture, people often urge companions to drink as much as possible so that they can build social connections and establish a happy and congenial atmosphere.65 This can also explain the gender difference in poisonings, as men are more engaged in social intercourse than women. In addition to widely practised social drinking, solitary drinking is also common for stress reduction and coping among Chinese.66

The current data showed that the fourth leading cause of acute poisoning was fumes/gases/vapours (mainly CO), which decreased from 12.5% in Zhao et al’s study to less than 11.4% in our study despite remaining in fourth place. This reduction is related to the improvement in dwelling conditions and preventive education on CO poisoning. With improvements in heating measures and advances in the fuel switching project from coal to natural gas in rural areas, a further decline in CO poisoning is expected in rural areas in China. There was a significant association between residency and month and reason for exposure to CO. Rural residents are more susceptible to CO poisoning than urban citizens, as local residents in remote villages in northern China use stoves to keep warm in winter, which can result in gas leaks due to chimney jam and lack of ventilation, and are common causes of CO poisoning in these areas. In contrast, CO poisoning in urban citizens may be explained by eating barbecued food and hotpots, well-known traditional Chinese cuisine that both require charcoal as fuel.67 In addition, almost all CO poisoning cases in our study were accidental, with the exception of one case of suicide.

In our study, the rate of patients staying in hospital for less than 48 hours is small compared with other studies. This was due to patients with poisoning usually being asked to remain in the observing room (available in our ED) for 48–72 hours in consideration of the complex doctor–patient relationship in China.

Our study was primarily limited by its retrospective nature, which resulted in missing patient data. Another limitation was that the data from a single centre teaching hospital, even with three branches, may not reflect the precise situation in this region. Hence, extensive data collection and analysis from other general hospitals in the region may depict the pattern of regional poisoning more accurately. In addition, the comparison between the two studies was rudimentary due to the absence of data standardisation.

Conclusion and suggestions

The present data provide additional insight into the epidemiology of acute poisoning in Shenyang. The findings demonstrated that more women than men presented with acute poisoning, and the most vulnerable age group was the young adult group aged 20–29 years. We also observed that the majority of poisoning cases were intentional, particularly suicidal in nature, and accidental poisonings were non-negligible. Our study indicated that therapeutic drugs were the most commonly used toxic agent group, followed by pesticides, alcohol and noxious gas. In addition, the pattern of acute poisoning was slightly altered when compared with 10 years ago. Poisoning due to analgesics and cold and cough medicines was more frequent than poisoning due to psychotropics in the therapeutic drugs poisoning group. In addition, poisoning due to paraquat and rodenticide exceeded poisoning due to organophosphate in the pesticide poisoning group.

Some suggestions are proposed based on the present study and include the following: First, vulnerable groups such as young adults deserve special consideration due to their weak coping capacity.34 Further investment is required to promote public health education on the rational use and safe storage of toxic agents as well as self-protection to reduce accidental poisoning.7 The upward trend in the prevalence of alcohol and drug use should receive more attention. Patients who attempt suicide must undergo psychiatric consultation as soon as possible. Early psychiatric consultation and identification may minimise the risk of further self-harm in suicidal cases.68 Lastly, relevant policies and regulations should be formulated and initiated immediately to restrict access to toxic agents, especially pesticides due to their high toxicity.5

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the library staff for providing language help.

Footnotes

Contributors: TL developed and directed the study. NW conceived and designed the survey questions on poisoning. BY coordinated data collection and carried out data cleaning. YZ performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors drafted, edited and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no 81301627 and no 81500628).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Research ethical approval was obtained from Shengjing Hospital Institutional Ethics Committee before study commencement.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1. Kalseen CD, Andur MO, Doull J. Casarett and Doull’s Toxicology. Newyork: Macmillan, 1986:10–17. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Senarathna L, Buckley NA, Jayamanna SF, et al. . Validity of referral hospitals for the toxicovigilance of acute poisoning in Sri Lanka. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:436–43. 10.2471/BLT.11.092114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Güloğlu C, Kara IH. Acute poisoning cases admitted to a university hospital emergency department in Diyarbakir, Turkey. Hum Exp Toxicol 2005;24:49–54. 10.1191/0960327105ht499oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eddleston M. Patterns and problems of deliberate self-poisoning in the developing world. QJM 2000;93:715–31. 10.1093/qjmed/93.11.715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gunnell D, Eddleston M, Phillips MR, et al. . The global distribution of fatal pesticide self-poisoning: systematic review. BMC Public Health 2007;7:357 10.1186/1471-2458-7-357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shah SM, Asari PD, Amin J. CLINICO-EPIDEMIOLOGICAL PROFILE OF PATIENTS PRESENTING WITH ACUTE POISONING. Ijcrr 2016;8:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Konradsen F, van der Hoek W, Cole DC, et al. . Reducing acute poisoning in developing countries--options for restricting the availability of pesticides. Toxicology 2003;192:249–261. 10.1016/S0300-483X(03)00339-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tang Y, Zhang L, Pan J, et al. . Unintentional Poisoning in China, 1990 to 2015: The Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Am J Public Health 2017;107:1311–5. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu QH, Jiang DF. Research Status of Acute Poisoning in China. Journal of Occupational Health and Damage 2011;26:238–9. in Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang J, Xiang P, Zhuo X, et al. . Acute poisoning types and prevalence in Shanghai, China, from January 2010 to August 2011. J Forensic Sci 2014;59:441–6. 10.1111/1556-4029.12334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang M, Fang X, Zhou L, et al. . Pesticide poisoning in Zhejiang, China: a retrospective analysis of adult cases registration by occupational disease surveillance and reporting systems from 2006 to 2010. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003510 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang BS, Chen L, Li XT, et al. . Acute Pesticide Poisoning in Jiangsu Province, China, from 2006 to 2015. Biomed Environ Sci 2017;30:695–700. 10.3967/bes2017.094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xm G, Jiang DF, Liu QH. Epidemiological study on 6011 cases of the acute poisoning during 2005~2009 year in Guangxi. Chinese Journal of New Clinical Medicine 2011;4:699–701. in Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 14. The 2010 population census of the People’s Republic of China. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/pcsj/rkpc/6rp/indexch.htm.

- 15. Chataut J, Adhikari RK, Sinha NP, et al. . Pattern of organophosphorous poisoning: a retrospective community based study. Kathmandu Univ Med J 2011;9:31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhao M, Ji XP, Wang NN, et al. . Study of poisoning pattern at China Medical University from 1997 to 2007. Public Health 2009;123:454–5. 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ahmadi A, Pakravan N, Ghazizadeh Z. Pattern of acute food, drug, and chemical poisoning in Sari City, Northern Iran. Hum Exp Toxicol 2010;29:731–8. 10.1177/0960327110361501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hanssens Y, Deleu D, Taqi A. Etiologic and demographic characteristics of poisoning: a prospective hospital-based study in Oman. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 2001;39:371–80. 10.1081/CLT-100105158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thomas SH, Bevan L, Bhattacharyya S, et al. . Presentation of poisoned patients to accident and emergency departments in the north of England. Hum Exp Toxicol 1996;152719:46660500602–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McCaig LF, Burt CW. Poisoning-related visits to emergency departments in the United States, 1993-1996. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 1999;37:817–26. 10.1081/CLT-100102460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ergun B, Cevik AA, Ilgin S, et al. . Acute drug poisonings in Eskisehir, Turkey: A retrospective study. Turkish Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2013;10:303–12. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meredith TJ. Epidemiology of poisoning. Pharmacol Ther 1993;59:251–6. 10.1016/0163-7258(93)90069-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhigang Z, Peiyi Z, Jianming G. Epidemiological analysis of 560 cases of acute poisoning. Beijing Med 2007;29:708–19. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thalappilli MC, Jimmy A. A profile of acute poisonings: A retrospective study. Journal of the Scientific Society 2015;42:156–60. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Malangu N. Acute poisoning at two hospitals in Kampala-Uganda. J Forensic Leg Med 2008;15:489–92. 10.1016/j.jflm.2008.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nair PK, Revi NG. One-Year Study on Pattern of Acute Pharmaceutical and Chemical Poisoning Cases Admitted to a Tertiary Care Hospital in Thrissur, India. Asia Pac J Med Toxicol 2015;4:79–82. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ramesha KN, Rao KB, Kumar GS. Pattern and outcome of acute poisoning cases in a tertiary care hospital in Karnataka, India. Indian J Crit Care Med 2009;13:152–5. 10.4103/0972-5229.58541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bari MS, Chakraborty SR, Alam MMJ, et al. . Four-Year Study on Acute Poisoning Cases Admitted to a Tertiary Hospital in Bangladesh: Emerging Trend of Poisoning in Commuters. Asia Pac J Med Toxicol 2014;3:152–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ, Horwood LJ. Risk factors and life processes associated with the onset of suicidal behaviour during adolescence and early adulthood. Psychol Med 2000;30:23–39. 10.1017/S003329179900135X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhao CJ, Dang XB, Su XL, et al. . Epidemiology of Suicide and Associated Socio-Demographic Factors in Emergency Department Patients in 7 General Hospitals in Northwestern China. Med Sci Monit 2015;21:2743–9. doi:10.12659/MSM.894819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang J, Jia C. Suicidal intent among young suicides in rural China. Arch Suicide Res 2011;15:127–39. 10.1080/13811118.2011.565269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cash SJ, Bridge JA. Epidemiology of youth suicide and suicidal behavior. Curr Opin Pediatr 2009;21:613–9. 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833063e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bundotich JK, Gichuhi MM. Acute poisoning in the Rift Valley Provincial General Hospital, Nakuru, Kenya: January to June 2012. South African Family Practice 2015;57:214–8. 10.1080/20786190.2014.975448 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang CW, Chan CL, Yip PS. Suicide rates in China from 2002 to 2011: an update. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2014;49:929–41. 10.1007/s00127-013-0789-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thomas M, Anandan S, Kuruvilla PJ, et al. . Profile of hospital admissions following acute poisoning--experiences from a major teaching hospital in south India. Adverse Drug React Toxicol Rev 2000;19:313–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tüfekçi IB, Curgunlu A, Sirin F. Characteristics of acute adult poisoning cases admitted to a university hospital in Istanbul. Hum Exp Toxicol 2004;23:347–51. 10.1191/0960327104ht460oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mowry JB, Brooks DE. 2014 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 32nd Annual Report. Clinical Toxicology 2015;53:962–1147. 10.3109/15563650.2015.1102927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lapatto-Reiniluoto O, Kivistö KT, Pohjola-Sintonen S, et al. . A prospective study of acute poisonings in Finnish hospital patients. Hum Exp Toxicol 1998;17:307–11. 10.1177/096032719801700604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Moradi M, Ghaemi K, Mehrpour O. A hospital base epidemiology and pattern of acute adult poisoning across Iran: a systematic review. Electron Physician 2016;8:2860–70. doi:10.19082/2860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kavalci C, Demir A, Arslan ED, et al. . Adult Poisoning Cases in Ankara: Capital City of Turkey. Int J Clin Med 2012;03:736–9. 10.4236/ijcm.2012.37A129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lee HL, Lin HJ, Yeh SY, et al. . Etiology and outcome of patients presenting for poisoning to the emergency department in Taiwan: a prospective study. Hum Exp Toxicol 2008;27:373–9. 10.1177/0960327108094609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lam SM, Lau AC, Yan WW. Over 8 years experience on severe acute poisoning requiring intensive care in Hong Kong, China. Hum Exp Toxicol 2010;29:757–65. 10.1177/0960327110361753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Liu CG, Jin F, Yuan GH. The History and Expectation of Classification Management of Drugs in China. [J] Chinese Journal of Pharmacovigilance 2013;10:348–51. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sy Y, Shang FF, Huang K. Status Quo and Countermeasures Research on Categorization Management of Medicine. Chinese Pharmaceutical Affairs 2016;30:32–4. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chen WW, Gao YL, Liu LS, et al. . Summary of China cardiovascular disease report 2016. Chinese Circulation Journal 2017;32:521–30. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wu P, Li LP, Jin J, et al. . Need for mental health services and service use among high school students in China. Psychiatr Serv 2012;63:1026–31. 10.1176/appi.ps.201200090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fang W, Liu T, Gu Z, et al. . Consumption trend and prescription pattern of opioid analgesics in China from 2006 to 2015. Eur J Hosp Pharm. (Published Online First: 27 January 2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48. Wang JS, Pan SF. Analysis of current clinical survey of chronic non-cancer pain-relief and opioid:the Chinese subgroup report of ACHEON study. J Journal of Chinese Physician 2016;18:492–6. in Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jeyaratnam J. Acute pesticide poisoning: a major global health problem. World Health Stat Q 1990;43:139–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jaiprakash H, Sarala N, Venkatarathnamma PN, et al. . Analysis of different types of poisoning in a tertiary care hospital in rural South India. Food Chem Toxicol 2011;49:248–50. 10.1016/j.fct.2010.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. van der Hoek W. Analysis of 8000 Hospital Admissions for Acute Poisoning in a Rural Area of Sri Lanka. Clin Toxicol 2006;44:225–31. 10.1080/15563650600584246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Howlader MAR, Hossain MZ, Morshed MG, et al. . Changing Trends of Poisoning in Bangladesh. Journal of Dhaka Medical College 2011;20:51–6. 10.3329/jdmc.v20i1.8582 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Page A, Liu S, Gunnell D, et al. . Suicide by pesticide poisoning remains a priority for suicide prevention in China: Analysis of national mortality trends 2006-2013. J Affect Disord 2017;208:418–23. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhang J, Xu H. The effects of religion, superstition, and perceived gender inequality on the degree of suicide intent: a study of serious attempters in China. Omega 2007;55:185–97. 10.2190/OM.55.3.b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang X, Li HS, Zhu QH, et al. . Trends in suicide by poisoning in China 2000-2006: age, gender, method, and geography. Biomed Environ Sci 2008;21:253–6. 10.1016/S0895-3988(08)60038-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wang J, Li Y, Wang X, et al. . Status Quo of Pesticide Use in China and Its Outlook [J]. Agricultural Outlook 2017;13:56–60. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang S, Zheng Q, Zhang PS, et al. . Epidemiological study of 357 acute paraquate poisoning cases [J]. Chinese Journal of Health Statistics 2013;30:251–2. in Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lee JW, Hwang IW, Kim JW, et al. . Common Pesticides Used in Suicide Attempts Following the 2012 Paraquat Ban in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 2015;30:1517–21. 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.10.1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Guan-Sheng MA, Zhu DH, Xiao-Qi HU, et al. . The drinking practice of people in China. Ying Yang Xue Bao 2005;27:362–5. in Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 60. National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. China national nutrition and chronic disease status report [in Chinese]. 2015. http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/jkj/s5879/201506/4505528e65f3460fb88685081ff158a2.shtml (accessed 15 Dec 2016).

- 61. Yuan T, Fan Q, Tang XZ, et al. . Analysis of acute poisoning in 640 cases. Practical Clinical Medicine 2009;10:27. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Thapa SR, Lama P, Karki N, et al. . Pattern of poisoning cases in Emergency Department of Kathmandu Medical College Teaching Hospital. Kathmandu Univ Med J 2008;6:209–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Afshari R, Majdzadeh R, Balali-Mood M. Pattern of acute poisonings in Mashhad, Iran 1993-2000. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 2004;42:965–75. 10.1081/CLT-200042550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Jayasinghe NR, Foster JH. Deliberate self-harm/poisoning, suicide trends. The link to increased alcohol consumption in Sri Lanka. Arch Suicide Res 2011;15:223–37. 10.1080/13811118.2011.589705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Li Y, Jiang Y, Zhang M, et al. . Drinking behaviour among men and women in China: the 2007 China Chronic Disease and Risk Factor Surveillance. Addiction 2011;106:1946–56. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03514.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hussong AM. Further refining the stress-coping model of alcohol involvement. Addict Behav 2003;28:1515–22. 10.1016/S0306-4603(03)00072-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Xue J, Sun Q, Wang Y, et al. . Features of Carbon Monoxide Poisoning in China. Iran J Public Health 2013;42:1192–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Linehan MM, Korslund KE, Harned MS, et al. . Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder: a randomized clinical trial and component analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:475–82. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.