Abstract

Objective

Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3), also known as Machado-Joseph disease, is the most common dominantly inherited ataxia. Despite advances in understanding this CAG repeat/polyglutamine expansion disease, there are still no therapies to alter its progressive fatal course. Here we investigate whether an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) targeting the SCA3 disease gene, ATXN3, can prevent molecular, neuropathological, electrophysiological and behavioral features of the disease in a mouse model of SCA3.

Methods

The top ATXN3-targeting ASO from an in vivo screen was injected intracerebroventricularly into early symptomatic transgenic SCA3 mice that express the full human disease gene and recapitulate key disease features. Following a single ASO treatment at 8 weeks of age, mice were evaluated longitudinally for ATXN3 suppression and rescue of disease-associated pathological changes. Mice receiving an additional repeat injection at 21 weeks were evaluated longitudinally up to 29 weeks for motor performance.

Results

The ATXN3-targeting ASO achieved sustained reduction of polyglutamine-expanded ATXN3 up to 8 weeks after treatment and prevented oligomeric and nuclear accumulation of ATXN3 up to at least 14 weeks after treatment. Longitudinal ASO therapy rescued motor impairment in SCA3 mice, and this rescue was associated with a recovery of defects in Purkinje neuron firing frequency and afterhyperpolarization.

Interpretation

This preclinical study established efficacy of ATXN3-targeted ASOs as a disease-modifying therapeutic strategy for SCA3. These results support further efforts to develop ASOs for human clinical trials in this polyglutamine disease as well as in other dominantly inherited disorders caused by toxic gain of function.

INTRODUCTION

Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3), also known as Machado-Joseph disease, is the most common dominantly inherited ataxia in the world, affecting an estimated 1 in 20,000 people1. Affected persons progressively lose motor control, leading to death within 10 to 20 years2. The progressive changes in SCA3 reflect widespread degenerative and neuropathological changes, including neuronal loss and gliosis in the deep cerebellar nuclei (DCN), pons, vestibular nuclei and other brainstem nuclei, spinocerebellar tracts, substantia nigra, thalamus, and globus pallidus3,4. SCA3 is one of nine neurodegenerative diseases caused by an expanded, polyglutamine-coding repeat in the disease gene5. The mutant SCA3 disease protein, ATXN3, acts through a dominant toxic mechanism that is still poorly understood1,6, and mice lacking ATXN3 are phenotypically normal7. Thus, suppression of the disease gene, ATXN3, represents a promising approach to slow or block the neurodegenerative cascade in SCA3.

Currently there is no effective treatment for this relentlessly progressive and fatal disease. In this report, we test antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) as a potential therapy for SCA3. ASOs represent a non-viral gene suppression approach that has emerged as a compelling therapeutic strategy for neurologic, oncologic, cardiac and metabolic disorders. Chemically modified ASOs can be designed to selectively bind complementary target RNA, resulting in RNase H-mediated cleavage of the targeted RNA or induced exon skipping8. ASOs targeting many neurodegenerative disease genes have undergone preclinical assessment in rodent models and, in some diseases, have advanced into human clinical trials including familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Huntington’s disease (HD)9–11. The first disease-modifying therapy in spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) employing exon-skipping ASOs was recently FDA- and EMA-approved following successful human clinical trials12,13.

Our group and others previously tested nucleotide-based gene silencing strategies as potential disease-modifying therapy in SCA3, including viral-mediated RNA interference14–16 and exon-skipping approaches17,18. While promising, these prior studies have been limited by various factors including – depending on the study – short-term treatment, spatially restricted silencing in the central nervous system (CNS), limited reduction of mutant ATXN3, or concerns about the extent to which the animal model replicates aspects of the human disease. Here we set out to perform an efficacy study not limited by these factors, building on our recent proof-of-principle study that established widespread ASO delivery and silencing of human mutant ATXN3 in a mouse model of SCA319. In this earlier study, we evaluated a collection of chemically modified ASOs targeting ATXN3 in cellular and mouse models of SCA319. We achieved widespread ASO delivery and efficient silencing of human mutant ATXN3 throughout affected brain regions, without signs of an adverse immune response to treatment. ASOs were delivered directly into the CNS by intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection, allowing the natural flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to distribute ASOs throughout the CNS, as supported by histological assessment in ASO-treated rodent and non-human primate studies19–22. From this short-term safety and efficacy study, we selected the best ASO candidate, ASO-5, for further evaluation here in a longitudinal preclinical study. Using a well characterized mouse model of SCA3 that expresses the full human disease gene, we sought to determine whether sustained suppression of the ATXN3 disease protein rescues key molecular, pathological, electrophysiological, and behavioral hallmarks of disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with the United States Public Health Service’s Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Genotyping was performed using tail biopsy DNA isolated prior to weaning and confirmed post mortem, as previously described19. Fragment analysis was used to assess the human ATXN3 repeat expansions (Laragen, San Diego, CA), with animals expressing repeat expansion of Q75 or greater included in behavioral studies. Animals were sex-, littermate- and age-matched for each study. For biochemical and histological analysis, animals were euthanized either at 12, 16, or 22 weeks of age after ASO treatment at 8 weeks, and tissue macro-dissected for histology and biochemical assessments, as previously described19. All treatment groups were blinded to the experimenter prior to analysis.

Antisense oligonucleotides

The anti-ATXN3 candidate ASO (ASO-5; GCATCTTTTCATTACTGGC) and a scrambled ASO control (ASO-Ctrl; GTTTTCAAATACACCTTC) used in this study were previously described19. Specifically, the ASOs have a gapmer design10 with eight unmodified deoxynucleotides with native sugar-phosphate backbone flanked on both sides by five 2′-O-methoxyethylribose modified ribonucleotides with phosphorothioate backbones. ASO-5 targets the 3′UTR of both human and mouse ATXN3. Oligonucleotides were synthesized as previously described23,24 and solubilized in PBS (without Ca2+ or Mg2+).

Stereotaxic mouse ICV ASO delivery

Stereotaxic administration of ASOs into the right lateral ventricle via ICV injections was performed as previously described19. Following surgery, weight, grooming activity and home cage activity were recorded for up to ten days.

RNA isolation and quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated from dissected brain tissue using Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Reverse transcription was performed on 0.5–1 μg of total RNA using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The cDNA was diluted 1:20 in nuclease-free water. iQ SYBR green quantitative PCR was performed on the diluted cDNA following the manufacturer’s protocol (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Average adjusted relative quantification analysis was performed using previously described primers6,19.

Immunoblotting

Protein lysates from macro-dissected diencephalon and cerebellar tissue were processed as previously described19 and stored at -80°C. 40 μg total mouse brain protein lysate were resolved in 4–20% gradient sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide (SDS) electrophoresis gels and transferred to 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with various antibodies: mouse anti-ATXN3 (1H9) (1:1000, MAB5360; Millipore, Billerica, MA), mouse anti-GFAP (1:20000, 3670S; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), rabbit anti-IBA1 (1:500, 016-20001; Wako, Osaka, Japan), rabbit anti-BAX (1:500, 2772S; Cell Signaling Technology, Danver, MA), mouse anti-BCL-2 (1:500, 610538; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), mouse anti-p62 (1:1000, ADI-SPA-902-D; Enzo Life Sciences, New York, NY), rabbit anti-BECLIN1 (1:1000, ab207612; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), mouse anti-GAPDH (1:5000, MAB374; Millipore, Billerica, MA), and rabbit anti-α-Tubulin (1:5000, #S2144; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Bound primary antibodies were visualized by incubation with peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:10000; Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, West Grove, PA) followed by treatment with the ECL-plus reagent (Western Lighting; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) and exposure to autoradiography films. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ analysis software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Immunohistochemistry

Whole brains perfused with PBS were processed as previously described19. Primary antibodies assessed include: mouse anti-ATXN3 (1H9) (1:1000, MAB5360; Millipore, Billerica, MA), rabbit anti-ASO (1:5000; Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Carlsbad, CA), rabbit anti-NeuN-488 conjugated (1:1000, ABN78A4; Millipore, Billerica, MA), mouse anti-GFAP (1:1000, #3670; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), rabbit anti-IBA1 (1:1000, 019-19741, WAKO, Richmond, VA), goat anti-OLIG2 (1:500, sc-19969, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), mouse anti-p62 (1:1000, ADI-SPA-902-D; Enzo Life Sciences, New York, NY), and rabbit anti-BECLIN1 (1:1000, ab207612; Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Imaging was performed using an IX71 Olympus inverted microscope (Melville, NY) or Nikon-A1 confocal microscope (Melville, NY) in the basilar pontine nuclei (denoted as pons) and deep cerebellar nuclei (DCN). Nuclear ATXN3 accumulation was quantified as previously described19.

Motor evaluation

Balance and coordination were tested by measuring the time needed to traverse a 5-mm square beam, as previously described16. Traversal time was recorded for each trial with a maximum of 20 seconds; falls from the beam were scored as 20 seconds. Paw slips below the beam and hindlimb dragging were also recorded for each trial. Locomotor activities were measured by placing the mice in a photobeam activity system open field apparatus (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA) for 30-minute trials on days when no other testing occurred. Total activity was calculated by measuring the total number of x/y-axis beam breaks. Body weights were recorded on the first day of behavior testing at each time point.

Brain slice preparation and electrophysiology

Parasagittal cerebellar slices were prepared as described previously25. Purkinje neurons from cerebellar lobules II-V were recorded using borosilicate glass patch pipettes with a 3–5 MΩ and filled with internal pipette recording solution containing the following (in mM): 119 K gluconate, 2 Na gluconate, 6 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 0.9 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 14 Tris-phosphocreatine, 4 MgATP, 0.3 tris-GTP, pH 7.3, osmolarity 290 mOsm. Recordings were made 1–5 hours after slice preparation in a recording chamber continuously perfused with carbogen-bubbled ACSF at 33°C at a flow rate of 2–3 mL/min. Data were acquired using an Axon CV-7B headstage amplifier, Axon Multiclamp 700B amplifier, Digidata 1440A interface, and pClamp-10 software (MDS Analytical Technologies, Sunnyvale, CA). In all cases, acquired data were digitized at 100 kHz. Voltage data were acquired in current-clamp mode with bridge balance compensation and filtered at 2 kHz. Cells were rejected if the series resistance changed by >20% during recording. Whole-cell somatic recordings were rejected if the series resistance rose above 15 MΩ, with most recordings having a series resistance of <10 MΩ. All voltages were corrected for a liquid junction potential of +10 mV26. Firing frequency was determined in Clampfit 1.2 (MDS Analytical Technologies) using a single 10 second cell-attached recording. Firing frequency histogram reflects compiled firing frequencies for all cells of each genotype divided into 25 Hz bins. Analysis of the afterhyperpolarization (AHP) was performed on recordings where the cell was held at −80 mV and injected with a series of escalating 1 second current pulses. The AHP was analyzed using the first spike from the first trace where there was no greater than a 50-millisecond delay to the spike from current injection onset. Reported AHP values were calculated by taking Vm at each time point (indicated times are the time after spike peak) and subtracting it from threshold. Threshold for each spike was defined as the Vm where dV/dt crosses 5% of the peak dV/dt during the rising phase of the spike.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using Prism (7.0; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). All statistical significance, except firing frequency, was tested using analysis of variance with a post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Variability about the mean is expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. Firing frequency, which didn’t exhibit Gaussian distribution, was reported using box (25–75 percentile) and whiskers (1–99 percentile) plot and assessed with Kruskal-Wallis test with a post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. All tests set the level of significance at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Dose-dependent ASO suppression of mutant ATXN3 in SCA3 transgenic mice

Our initial limited, proof-of-principle study identified ASO-5 as a promising anti-ATXN3 ASO19. In preparation for a longitudinal efficacy study, we first sought to determine an optimal ASO-5 dose for safe and effective suppression of mutant ATXN3 (mutATXN3) in homozygous YAC-Q84 (Q84/Q84) transgenic mice. The Q84/Q84 SCA3 mouse model expresses the full-length human ATXN3 disease gene harboring a pathogenic CAG expansion at near endogenous levels and exhibits disease-relevant neuropathological changes and motor deficits as early as 6 weeks of age that progress in severity with age16,27. Its expression of the full human disease gene and recapitulation of human disease hallmarks make Q84/Q84 mice well-suited for longitudinal preclinical assessment of potential SCA3 therapies.

Sex-matched 8-week-old Q84/Q84 mice were administered an ASO-5 dose ranging from 300 to 1000 μg (n=4 mice per dose) by stereotaxic ICV injection into the right lateral ventricle (Fig 1A). For comparison, Q84/Q84 or wild type (WT) littermate controls (n=4 mice per genotype) received PBS vehicle-only ICV injections. Mice were subsequently monitored according to University of Michigan Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines, with no post-surgical adverse events occurring at any tested dose. Treated mice were sacrificed four weeks after injection and brains bisected along the midline. The left and right hemispheres were processed for biochemical and immunohistochemical analysis, respectively. All treatment groups were blinded to the experimenter prior to analysis.

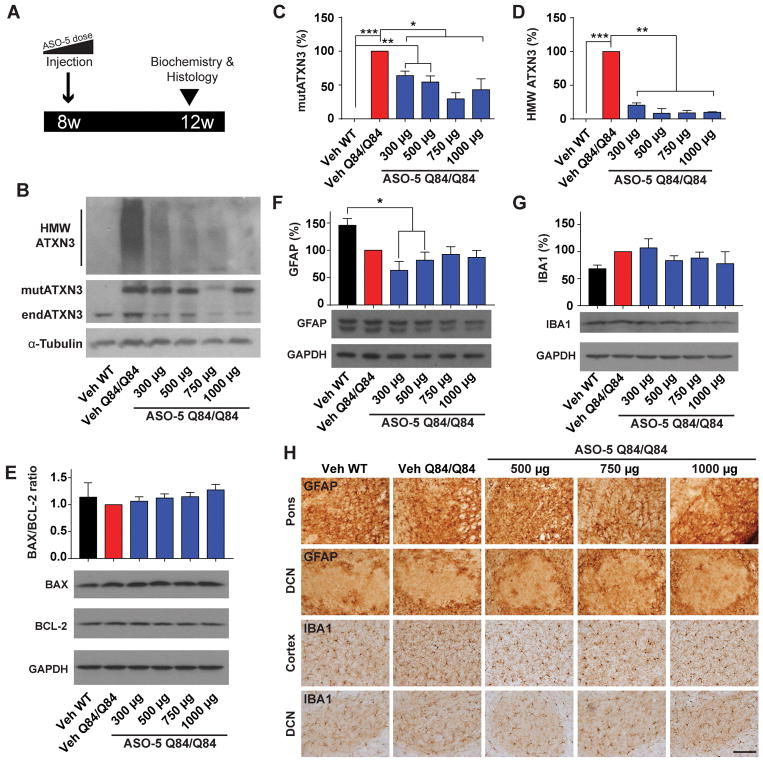

Figure 1. Dose-dependent ASO suppression of mutant ATXN3 and tolerability in homozygous SCA3 transgenic mice.

(A) ASO-5 dose response study design. Sex- and littermate-matched Q84/Q84 mice received an intracerebroventricular injection of ASO-5 (300–1000 μg) or vehicle (Veh) at 8 weeks of age. Brains were harvested four weeks after injection for analysis. (B) Representative western blot and quantification of (C) soluble mutant human ATXN3 (mutATXN3) and (D) high molecular weight (HMW) ATXN3 protein levels from diencephalon protein lysates four weeks after ASO injection. (E) Western blot and quantification of BAX/BCL-2 protein expression ratio in the mouse diencephalon four weeks after treatment. (F) Western blot and quantification of GFAP and (G) IBA1 protein levels in the mouse diencephalon four weeks following treatment. (H) Anti-GFAP immunohistochemical staining of pons and DCN and anti-IBA1 staining of cortex and DCN four weeks following ASO injection. Data (mean ± SEM) are reported relative to Veh Q84/Q84 treated mice (n=4 per dose). One-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001). Scale bar, 200 μm.

Because of the high concentration of affected diencephalon nuclei in post-mortem SCA3 patient brains (e.g. pons, olivary nuclei, vestibular nuclei, cranial nerve nuclei), we focused our biochemical analysis on diencephalic tissue3,28,29. By immunoblot analysis, ASO-5 significantly reduced diencephalic mutATXN3 expression in a dose-dependent manner, though all doses showed efficacy (p<0.05) (Fig 1B and 1C). Mice that received 750 μg of ASO-5 exhibited the greatest mutATXN3 suppression, reducing levels to 29% ± 9% relative to vehicle-treated Q84/Q84 mice. Immunoblot analysis also revealed a striking rescue in the accumulation of high molecular weight (HMW) ATXN3 oligomers at all doses, reducing ATXN3 accumulation by more than 75% at the smallest dose (300 μg) and by about 90% for all doses greater than 500 μg relative to vehicle-treated Q84/Q84 mice (p<0.01) (Fig 1B and 1D).

No evidence of apoptosis or gliosis upon ASO-5 treatment in SCA3 mouse brain

To evaluate possible ASO-induced cellular toxicity with increasing doses, immunoblot analysis was performed for the pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins BAX and BCL-2, respectively. Quantitation of BAX and BCL-2 revealed no increase in the BAX/BCL-2 ratio with increasing ASO doses in the mouse diencephalon relative to vehicle-treated WT or Q84/Q84 littermates four weeks after injection, indicating no evident toxicity at tested doses (Fig 1E). Gliosis occurs in SCA33,30 and can also be a potential adverse effect of ASO treatment31. To determine the tolerability of ASOs at increasing doses, treated mice were assessed for astrogliosis and microgliosis four weeks after treatment. Immunoblot analysis revealed no ASO-mediated increases in the astrocyte marker GFAP (Fig 1F) or microglia marker IBA1 (Fig 1G) in the diencephalon at any tested dose relative to vehicle-treated WT or Q84/Q84 littermates, although a significant decrease in GFAP protein was observed in mice receiving 300 μg and 500 μg (p<0.05) (Fig 1F). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed no observable differences in astrocyte or microglia density, cellular structure, or localization four weeks following any ASO-5 dose (Fig 1H). Thus, no overt gliosis occurred at effective ASO-5 doses.

Sustained ASO-mediated suppression of mutant and oligomeric ATXN3 protein at least eight weeks after injection into SCA3 mice

Guided by the above results, we selected 700 μg of ASO-5 as an effective and safe dose to advance into preclinical studies. To determine the duration of ASO-5-mediated suppression of mutATXN3, we performed longitudinal biochemical assessments of Q84/Q84 or WT mice following treatment. Sex- and littermate-matched Q84/Q84 mice (n=6 per experimental group) received an ICV bolus injection of PBS vehicle, ASO-5, or non-specific control ASO (ASO-Ctrl) at 8 weeks of age. For comparison, WT sex-matched littermates similarly received an ICV injection of vehicle. Treated brains were harvested 4, 8, or 16 weeks after injection (i.e. at 12, 16, or 22 weeks of age) and bisected for biochemical and immunohistochemical analysis (Fig 2A). The following biochemical results are reported for the diencephalon dissected from the left hemisphere.

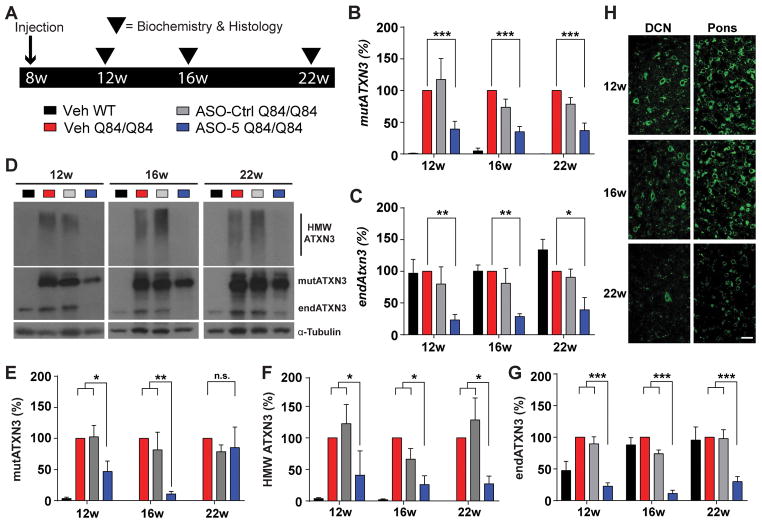

Figure 2. ASO-mediated suppression of mutant and oligomeric ATXN3 protein is sustained at least eight weeks after injection in SCA3 mice.

(A) Longitudinal trial design to assess sustained ATXN3 reduction in Q84/Q84 mice. Sex- and littermate-matched homozygous mice received an intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection of ASO-5 (700 μg) or vehicle (Veh) at 8 weeks of age. Brains were harvested at 12, 16 or 22 weeks of age for biochemical and histological analyses. Quantification of (B) human mutant ATXN3 (mutATXN3) and (C) mouse endogenous (endATXN3) Atxn3 transcript levels from treated mouse diencephalon. (D) Representative immunoblots and quantification of (E) soluble mutant ATXN3 (mutATXN3), (F) high molecular weight (HMW) ATXN3, and (G) endogenous ATXN3 (endATXN3) protein in the diencephalon at 12 weeks, 16 weeks, and 22 weeks of age. Data (mean ± SEM) are reported relative to vehicle-treated Q84/Q84 samples (n=4–6 per condition). Two-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001). (H) Representative anti-ASO immunofluorescent images of pons and DCN of ASO-treated mice at 12, 16, and 22 weeks. Scale bar, 25 μm.

By quantitative PCR, ASO-5 suppressed mutATXN3 transcript levels by ~50% over time (Fig 2B), and this transcriptional repression was maintained up to at least 22 weeks of age (p<0.05). A significant reduction in endogenous murine Atxn3 transcript levels was also observed in treated mice up to at least 22 weeks of age (p<0.01), consistent with the fact that ASO-5 targets both human and murine ATXN3 transcripts (Fig 2C).

Anti-ATXN3 immunoblot analysis confirmed highly stable and efficient suppression of the human disease protein (Fig 2D). MutATXN3 protein expression levels were significantly reduced in ASO-treated mice at both 12 weeks (p<0.05) and 16 weeks (p<0.01), with the greatest reduction occurring at 16 weeks of age (10.77% ± 2.08%) relative to vehicle-treated Q84/Q84 mice. Whereas soluble mutATXN3 levels returned to vehicle-treated Q84/Q84 mouse levels by 22 weeks (Fig 2E), complete reduction of oligomeric HMW ATXN3 to vehicle-treated WT mouse levels persisted at all time points (p<0.01) (Fig 2F). ASO-5 treated mice also exhibited significant reductions in endogenous ATXN3 protein levels at all time points, with the greatest reduction also occurring at 16 weeks (11.49% ± 4.99%, p<0.001) (Fig 2G).

The above protein and RNA analysis of brainstem lysates confirmed ASO delivery and ATXN3 suppression broadly in the diencephalon but does not shed light on whether selectively vulnerable neuronal populations in the SCA3 brain were successfully targeted. Employing immunofluorescence with an anti-ASO antibody, we assessed ASO-5 delivery and retention in the pons and DCN (Fig 2H), two subcortical regions known to undergo significant neuronal loss in post-mortem SCA3 patient brains3,28,29. Fourteen weeks after injection, ASO levels in the pons and DCN were equal to or greater than that of surrounding brain structures, confirming that these key disease-affected regions are readily targetable. ASO signal intensity remained high at the 16-week time point but was diminished by 22 weeks in both the pons and DCN. This loss of ASO signal at 22 weeks was accompanied by a concomitant increase in some immunoblotted ATXN3 protein species.

ASO-5 prevents nuclear sequestration of ATXN3 in vulnerable brain regions at least 14 weeks after injection

Redistribution of polyglutamine-expanded ATXN3 from the cytoplasm into neuronal nuclei appears to be an early and critical step in the SCA3 disease process1. For example, expressing polyglutamine-expanded ATXN3 attached to a nuclear export signal ameliorated disease in a mouse model of SCA332. The Q84/Q84 mouse is known to show increased nuclear concentration of ATXN3 as early as 6 weeks of age16, two weeks before ASO injection in our study. Thus, we next sought to investigate whether ASO-5 ICV injection into already symptomatic 8-week-old Q84/Q84 mice could rescue and prevent further nuclear accumulation of ATXN3 in affected neuronal nuclei over time.

Brain sections harvested from treated mice at 12, 16, and 22 weeks were immunofluorescently labeled with anti-NeuN (data not shown) and anti-ATXN3 antibodies, then co-stained with DAPI to label nuclei. Average integrated density of ATXN3 signal contained within NeuN-positive neuronal nuclei was calculated from confocal images taken of pons (Fig 3A and 3B) and DCN (Fig 3D and 3E) using ImageJ analysis software (n=6 mice per treatment group, 3 images per mouse). A single ASO-5 treatment reduced neuronal nuclear ATXN3 to vehicle-treated WT levels in pontine and DCN neurons up to at least 22 weeks of age (p<0.0001). These results also imply that the nuclear accumulation of ATXN3 that occurred prior to injection at 8 weeks of age was reversed by ASO-5 treatment.

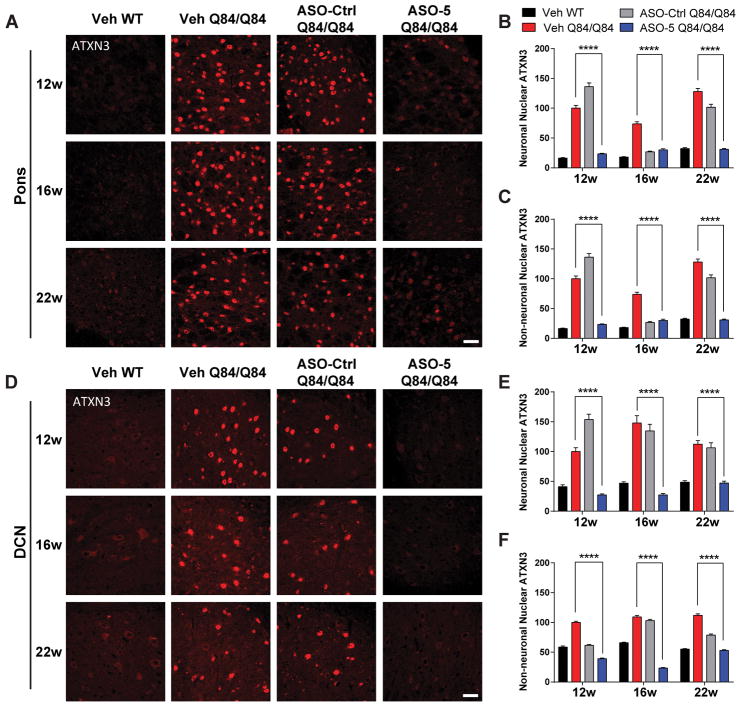

Figure 3. A single ASO-5 injection prevents nuclear accumulation of ATXN3 in vulnerable brain regions of SCA3 mice.

(A) Anti-ATXN3 immunofluorescence in pons at 12, 16, and 22 weeks of age in ASO- or vehicle-treated mice. Quantified integrated density of ATXN3 immunofluorescence in (B) NeuN-positive neuronal nuclei and (C) NeuN-negative non-neuronal nuclei in the pons. (D) Anti-ATXN3 immunofluorescence in DCN at 12, 16, and 22 weeks of age in ASO or vehicle-treated mice. Quantified integrated density of ATXN3 immunofluorescence in (E) NeuN-positive neuronal nuclei and (F) NeuN-negative non-neuronal nuclei in the DCN. n=6 mice per condition, 3 images from pons or DCN quantified per mouse. Data (mean ± SEM) are reported relative to vehicle-treated Q84/Q84 mice. Two-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey test (****p<0.0001). Scale bar, 25 μm.

We note that at 16 weeks ASO-Ctrl also led to a significant reduction in both neuronal and non-neuronal nuclear accumulation of ATXN3 compared to vehicle (Fig 3A–E). This result is potentially intriguing as the 16-week time point is also when we see the strongest effects of ASO-5 mediated ATXN3 reduction, suggesting a non-specific effect of ASO therapy. We did not investigate this result further, however, as ASO-Ctrl showed no effect on levels of soluble or HMW mutant ATXN3 species (Fig 2D–F).

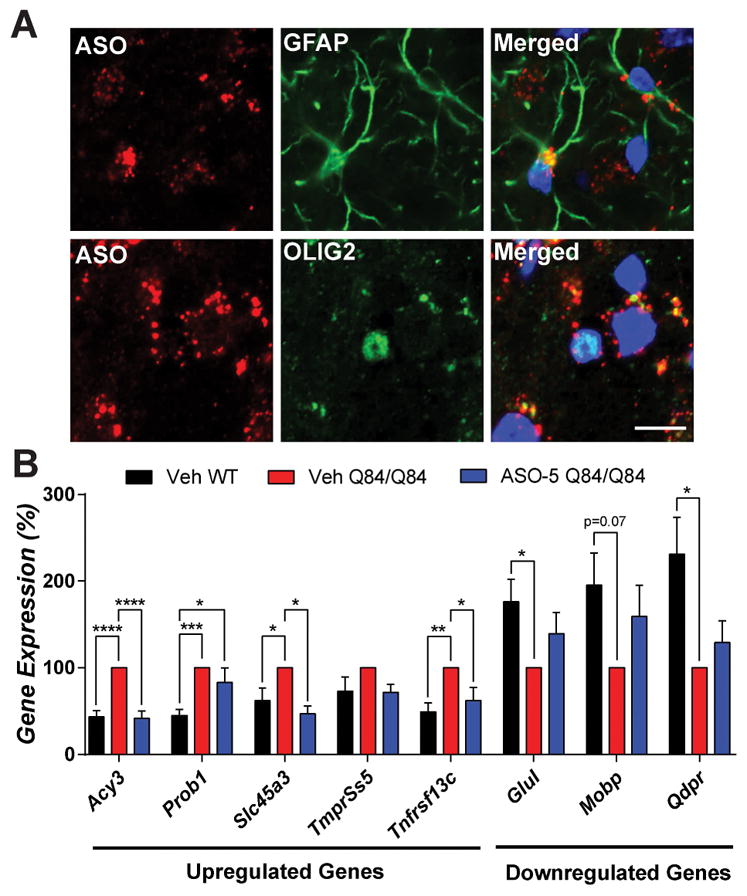

ASO-5 rescues differentially expressed pontine SCA3 mouse transcripts

A recent study by our group revealed pontine transcriptional changes in several SCA3 mouse models particularly in non-neuronal cells, suggesting glia and oligodendrocytes play an underappreciated role in disease6. To investigate whether glial cells are susceptible to ASO treatment, we quantified ATXN3 nuclear density in NeuN-negative, non-neuronal cells in the pons (Fig 3A and C) and DCN (Fig 3D and F). Analysis confirmed that nuclear accumulation of ATXN3 is indeed enriched in glial cells in Q84/Q84 mice and is reduced to and maintained at vehicle-treated WT levels for at least 14 weeks after ASO-5 treatment (p<0.0001). To determine whether reduction of nuclear ATXN3 in non-neuronal cell types was the direct result of ASO uptake, ASO-treated brain sections were immunofluorescently labeled with antibodies against ASO-5 and the astrocyte marker GFAP or the oligodendrocyte marker OLIG2. Confocal imaging of the pons confirmed ASO uptake into both astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, confirming non-neuronal cells are directly susceptible to ASO delivery and that ASO-mediated reductions in non-neuronal nuclear ATXN3 is likely not the result of an indirect non-cell autonomous mechanism (Fig 4A).

Figure 4. ASO-5 treatment rescues key differentially expressed diencephalic transcripts in SCA3 mice.

(A) Anti-ASO and anti-GFAP or anti-OLIG2 immunofluorescence in pons at 16 weeks of age in ASO-treated mice. (B) The differentially expressed transcripts in SCA3 mice shown were originally identified by Ramani et. al., 2017 HMG. Vehicle-treated WT (Veh WT, black), vehicle-treated Q84/Q84 (Veh Q84/Q84, red) and ASO-5 treated Q84/Q84 (ASO-5 Q84/Q84, blue) mice were injected at 8 weeks, and diencephalon transcripts were then assessed at 22 weeks of age. Data (mean ± SEM) are reported relative to vehicle treated Q84/Q84 mice (n=4–6). One-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001). Scale bar, 10 μm.

Prevention of ATXN3 nuclear accumulation by ASO-5 coincided with transcriptional rescue of several key oligodendrocyte-enriched genes dysregulated in the pons of SCA3 mice. Disease-specific oligodendrocyte-enriched genes6 were selected for transcriptional analysis in the diencephalon of vehicle-treated versus ASO-5 treated mice at 22 weeks of age (Fig 4B). Of the eight transcripts analyzed, six were confirmed to exhibit significant gene expression changes in vehicle-treated Q84/Q84 mice compared to WT mice. Disease-specific differential expression of three of the six significantly altered genes (Acy3, Slc45a3, Tnfrsf13c) was fully rescued in ASO-5 treated Q84/Q84 mice, and expression of the remaining three genes trended towards WT expression levels but did not reach statistical significance. Thus, ASO-5 treatment partially rescues SCA3-specific transcriptional changes in Q84/Q84 mice.

ASO-5 rescues motor phenotypes in Q84/Q84 mice

We next sought to determine whether sustained ASO-mediated mutATXN3 suppression could rescue motor deficits in symptomatic Q84/Q84 mice. A previous study of Q84/Q84 mice identified motor deficits by 6 weeks of age that worsened over time16. For the current study, longitudinal behavioral assessments included open field activity and balance beam performance, which were assessed at 7 weeks, one week before the first ASO-5 or vehicle injection, and then again at 4 or 5-week intervals after injection up to 29 weeks of age. Because the ASO concentration in Q84/Q84 mouse brain was substantially diminished by 22 weeks of age, we added a second ASO-5 or vehicle injection at 21 weeks (Fig 5A). Experimental groups included sex- and littermate-matched, vehicle-treated WT and Q84/Q84 mice, and ASO-5 treated Q84/Q84 mice (n=12–19 mice per group).

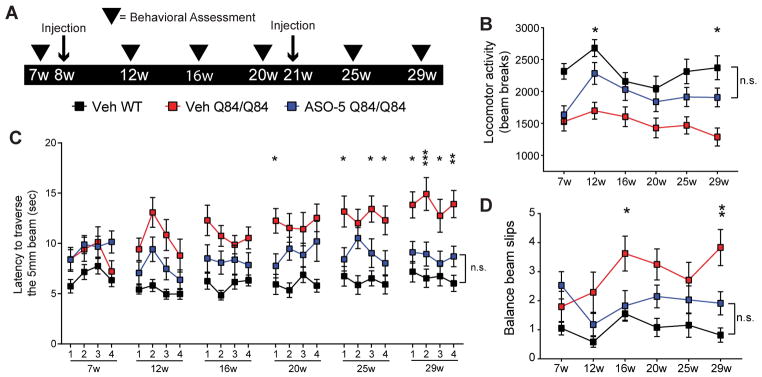

Figure 5. ASO-5 fully rescues motor phenotypes in SCA3 mice.

(A) Longitudinal trial design to assess effect of sustained ATXN3 reduction on motor phenotypes in Q84/Q84 mice. Sex- and littermate-matched homozygous mice received two intracerebroventricular (ICV) injections of ASO-5 (700 μg) or vehicle (Veh), at 8 and 21 weeks of age. Behavioral assessments (arrowheads) were completed pre- and post-treatment at 7, 12, 16, 20, 25, and 29 weeks of age. (B) Quantification of average locomotor activity over time in vehicle-treated Q84/Q84 (Veh Q84/Q84, red), ASO-5 treated Q84/Q84 mice (ASO-5 Q84/Q84, blue), and vehicle-treated WT mice (Veh WT, black), determined by mean number of beam breaks in a 30-minute open-field test (mean ± SEM). Quantification of (C) time to traverse the beam (points represent the mean of two consecutive trials on each of the four days of testing ± SEM) on 5-mm-squared beam and (D) number of limb slips (points represent average number of slips on day 4 ± SEM). Test group size used in motor tests ranged from 12–19 animals. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey test, graphs present statistical data comparisons of Veh Q84/Q84 relative to ASO-5 Q84/Q84 (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; n.s.= not significant).

Open field activity assessment confirmed decreased locomotor activity in Q84/Q84 mice at 7 weeks of age, just prior to ASO treatment (Fig 5B). At 12 weeks, the time of first assessment after injection, ASO-5 treated mice exhibited a complete rescue in open field locomotor activity which persisted at the 29-week endpoint (Fig 5B). Abnormalities in the balance beam test (increased traversal time and beam slips), which first became evident in vehicle-treated Q84/Q84 mice at 12- and 16-weeks, respectively, were also rescued by ASO-5 treatment at the endpoint assessment (p<0.05) (Fig 5C and D). Decreased weight, which is characteristic of Q84/Q84 mice, was not altered by ASO-5 treatment at any time point (data not shown), suggesting no overt effect of ASO-5 on peripheral tissues.

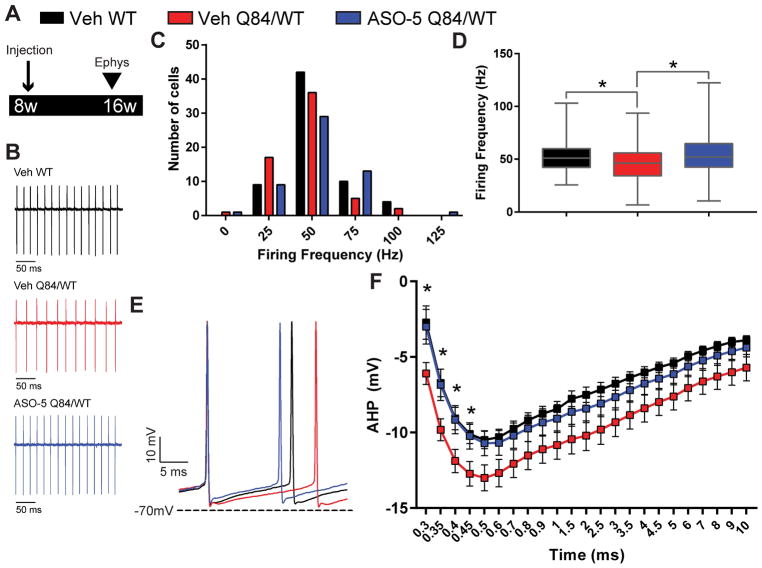

ASO-5 reverses slowed firing frequency in SCA3 Purkinje neurons

Abnormalities in Purkinje neuron physiology have previously been observed in Q84 mice25. To determine whether ASO-5 treatment rescues SCA3 Purkinje neuron function, extracellular recordings were performed in cerebellar slices from Purkinje neurons of WT and hemizygous Q84/WT mice at 16 weeks of age, 8 weeks after ASO-5 or vehicle injection (n=8–10 mice, Fig 6A). Purkinje neurons normally exhibit spontaneous repetitive spiking33. In vehicle-treated Q84/WT Purkinje neurons, recordings revealed an increased proportion of cells firing at an abnormally low frequency (Fig 6B and C). Median firing frequency was significantly reduced in vehicle-treated Q84/WT mice relative to vehicle-treated WT mice, and this slowed firing phenotype was rescued in ASO-5 treated Q84/WT mice (Fig 6D). This finding is reminiscent of a recent study in mouse models of another polyglutamine ataxia, spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA2), showing that an ASO targeting ATXN2 could rescue slowed firing of Purkinje neurons22. Together, these findings point to Purkinje neuron function as a target for ASO therapy across multiple ataxia models.

Figure 6. ASO-5 treatment reverses slowed firing frequency in SCA3 Purkinje neurons.

(A) Schematic of electrophysiologic study design. Hemizygous Q84/WT mice were injected with either vehicle or ASO-5 (700 μg) at 8 weeks of age and Purkinje cells were recorded at 16 weeks of age. (B) Representative patch clamp recordings of spontaneous firing in Purkinje neurons from vehicle-treated WT (Veh WT, black, n=65), vehicle-treated Q84/WT (Veh Q84/WT, red, n=61), and ASO-5 treated Q84/WT (ASO-5 Q84/WT, blue, n=53) mice. (C) Histogram of Purkinje neuron firing frequencies with 25 Hz bins. (D) Median firing frequency plotted using box (25–75 percentile) and whiskers (1–99 percentile) plot. Kruskal-Wallis test with a post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (*p<0.05). (E) Representative traces and (F) quantification (mean ± SEM) of afterhyperpolarization (AHP) in Veh Q84/WT, Veh WT and ASO-5 Q84/WT Purkinje cells. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey test (*p<0.05).

Slow Purkinje neuron firing, which is observed in many models of ataxia34–36, has been linked in SCA1 and SCA2 to deepening of the afterhyperpolarization (AHP) following each spike34,35. Consistent with findings in other models of ataxia, whole-cell patch clamp recordings of Purkinje neurons from treated mice (Fig 6E) revealed a deeper AHP in vehicle-treated Q84/WT mice that is rescued by ASO-5 treatment (p<0.05) (Fig 6F). Together, these data suggest that the deeper AHP observed in Q84/WT mice underlies the slowed Purkinje cell firing and that reducing mutATXN3 levels with ASO-5 treatment can improve aberrant electrophysiology in this critically important neuronal population in SCA3.

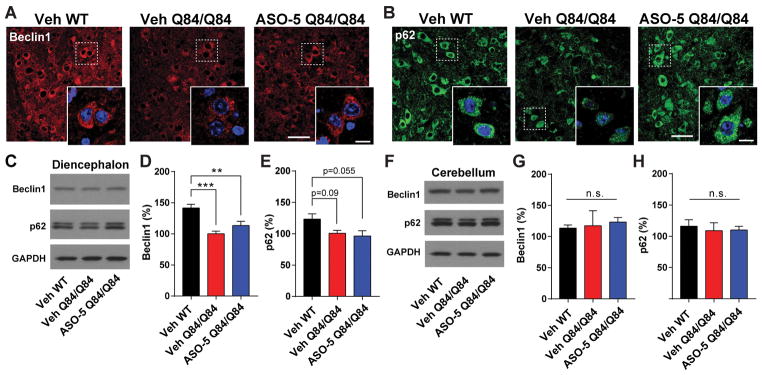

No evidence of macroautophagy exacerbation in ASO-5 Q84/Q84 treated mouse brains

Impairments in autophagy have been associated with age- and disease-related neuronal dysfunction37,38. A recent report suggests that, in addition to autophagy’s role in regulating clearance of misfolded proteins like polyglutamine-expanded ATXN3, autophagy may itself be regulated by ATXN3 in normal and disease states39,40. Specifically, WT ATXN3 has been reported to stabilize the essential autophagy adapter protein Beclin1, whereas reducing ATXN3 levels or introducing a polyglutamine-expansion into ATXN3 destabilizes and therefore reduces Beclin1 levels, in the process impairing autophagy39. Consistent with these observations, a recent study reported reduced Beclin1 protein levels in post-mortem SCA3 human disease brains39,41. Thus, it is conceivable that ASO-mediated reduction of ATXN3 could have the unintended, and potentially deleterious, effect of altering autophagy pathways.

Accordingly, we assessed the effect of mutATXN3 expression, as well as of ASO-mediated reduction in ATXN3 levels, on autophagy-related proteins in Q84/Q84 mice. Anti-Beclin1 immunofluorescence in the pons at 16 weeks revealed reduced Beclin1 expression in vehicle and ASO-5 treated Q84/Q84 mice relative to WT mice (Fig 7A). Protein analysis of diencephalic lysates at 16 weeks (Fig 7C and 7D) confirmed that vehicle-treated WT mice had approximately 50% greater Beclin1 protein level than either vehicle or ASO-5 treated Q84/Q84 mice (p<0.001, n=5–6 mice per treatment group). Importantly, ASO-5 mediated suppression of ATXN3 did not further magnify the reduction in Beclin1 expression in Q84/Q84 mice, evidenced both by immunoblot analysis and immunofluorescence of the pons in treated mice. In contrast to the pons, the cerebellum of vehicle or ASO-5 treated Q84/Q84 mice showed no change in Beclin1 levels relative to WT vehicle-treated mice (Fig 7F and 7G), suggesting potential region-specific autophagic dysfunction in SCA3.

Figure 7. ASO-5 reduction of ATXN3 does not exacerbate changes in autophagy pathway proteins.

Vehicle-treated WT (Veh WT), Vehicle-treated Q84/Q84 (Veh Q84/Q84) and ASO-5 treated Q84/Q84 (ASO-5 Q84/Q84) mice were injected at 8 weeks and tissue harvested at 16 weeks for histological and biochemical assessment (n=6 per condition). Representative immunofluorescence images of (A) Beclin1 and (B) p62 in the pons with magnification insets. Scale bar, 50 μm; inset scale bar, 10 μm. Representative western blots and quantification of Beclin1 and p62 protein expression in the (C–E) diencephalon and (F–H) cerebellum of treated mice. Data (mean ± SEM) are reported relative to Veh Q84/Q84-treated mice (n=6). One-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey test (*p<0.05;***p<0.001; n.s.= not significant).

Finally, we assessed the expression and localization of the ubiquitin-binding adapter protein p62, which is involved in selective autophagy. Previous studies have shown that p62 localizes to protein aggregates in many neurodegenerative diseases including SCA3 and may play a protective role in autophagic clearance of polyglutamine disease proteins28,29,41,42. By immunoblot analysis, diencephalic (Fig 7C and 7E) and cerebellar (Fig 7F and 7H) p62 expression levels did not differ across vehicle-treated WT, vehicle-treated Q84/Q84, or ASO-5 treated mice. We did, however, observe small, nuclear p62-positive puncta in the pons of Q84/Q84 vehicle-treated mice at 16 weeks of age, which were nearly absent in vehicle-treated WT or ASO-5 treated Q84/Q84 mice (Fig 7B). Rather than forming single large intranuclear aggregates of ATXN3, Q84/Q84 mice typically exhibit small, intranuclear ATXN3-positive inclusions in pontine neurons. Thus, the presence of p62-positive nuclear structures in neurons of Q84/Q84 mice may reflect p62 localization to ATXN3 oligomers or aggregates, which are ameliorated following ASO-5 mediated reduction of mutATXN3 treatment.

DISCUSSION

Currently there are no disease-modifying therapies available for dominantly inherited neurodegenerative diseases. The present study establishes robust and prolonged suppression of mutant expanded ATXN3 by an RNA-targeting therapy in Q84/Q84 mice, a progressive model of SCA3 expressing the precise human disease gene target. Sustained suppression of the disease protein resulted in the correction of a wide range of disease-associated features including molecular, physiological, neuropathological and behavioral phenotypes. This builds on recent work17–19 to establish the ability of nucleotide-based gene silencing to mitigate the broad range of disease phenotypes associated with expression of the mutant human ATXN3 gene. The results add to the growing promise of ASO therapy for dominantly inherited diseases, including other polyglutamine diseases such as HD, spinobulbar muscular atrophy and SCA2.

While previous gene silencing approaches for SCA3 have shown promise, they have not always achieved sufficient efficacy and safety in vivo to support continuation into human clinical trials. For example, our previous RNA interference preclinical study achieved safe and life-long suppression of mutATXN3 in Q84/Q84 mouse cerebellum, but failed to rescue any motor deficits, presumably due to the localized nature of delivery16. In contrast, ASO-5 treatment of post-symptomatic Q84/Q84 mice in the current study fully rescued locomotor activity, suggesting that CSF-dependent ASO delivery reaches the various nuclei and circuitry underlying the progressive motor, balance, and coordination deficits in SCA3. Importantly, sustained ASO-5 exposure was not accompanied by evidence of induced gliosis or apoptosis in vulnerable brain regions, and no adverse events were observed even at the highest ASO doses. These results further support the growing evidence from preclinical animal and human clinical ASO trials demonstrating sustained, widespread, and well-tolerated ASO delivery to the CNS following longitudinal ICV or intrathecal delivery20,22. In support of the tolerability of ASOs for SCA3, recent elegant work from Toonen et al., assessed exon-skipping of the CAG repeat containing exon 10 in ATXN318. While this exon-specific approach has the advantage that it would likely prevent deleterious effects of loss of ATXN3 function, whether it is sufficiently robust to effectively silence the disease gene requires further study.

To date, published SCA3 studies reveal a neuron-centric view of disease. Though neuronal loss must be a major contributor to the progressive symptoms of SCA3, studies have also begun to implicate non-neuronal cell dysfunction in SCA36,43. For example, in our recent study exploring differentially expressed genes in mouse models of SCA3, the most abundantly altered transcripts reside in oligodendrocytes6. The reasons for this preferential effect on oligodendrocytic transcription are unclear, but our demonstration here that ATXN3 accumulates in the nuclei of non-neuronal cells in the diencephalon of Q84/Q84 mice is consistent with a cell-autonomous effect. ASO-5 treatment and confirmed ASO uptake in astroglia and oligodendrocytes eliminated this nuclear accumulation of mutATXN3 in non-neuronal cells with a corresponding transcriptional rescue of several oligodendrocyte-enriched genes, consistent with a direct effect of ATXN3 on non-neuronal cells in disease. The ability of ASOs to target both neuronal and non-neuronal cells may prove advantageous for SCA3 therapy.

Our finding of reduced Purkinje neuron firing frequency in Q84/WT mice adds to the literature identifying altered Purkinje neuron firing frequency in other polyglutamine ataxia models, including transgenic mouse models of SCA135 and SCA244 as well as a viral rodent model of SCA636. The reduction in firing frequency we observed is associated with a deeper AHP, and ASO treatment in Q84/WT mice normalizes the AHP and rescues slowed firing. Although the molecular mechanism causing slowed firing in Q84/WT mice was not explored here, previous experiments have suggested that impairment of Kv3 family potassium channels in this mouse model25 contribute to spiking abnormalities, and Purkinje neurons from Kv3.3 knockout mice show slower firing and a deeper AHP45. Moreover, the rescue of motor impairment through pharmacologic targeting of ion channels in SCA1 mice46 and ASO treatment in SCA2 mice22 is associated with normalizing of Purkinje neuron firing frequency, suggesting that ASO treatment in SCA3 mice improves Purkinje neuron physiology in a behaviorally relevant manner. That said, the neural circuitry underlying motor activity is far more complex than simply the regulation of Purkinje neuron firing. Indeed, the more widespread CNS distribution of ASO-5 in the current study compared to our earlier miRNA-based study16, in which ATXN3 reduction was confined to the cerebellum, may explain why correction of motor deficits was observed in the current but not in the prior study.

Recent studies suggest a role for ATXN3 in autophagy, both normally and in the disease state37–41,47,48. This putative function of ATXN3 poses a potential concern for unintended impairments in autophagy following ATXN3 silencing. We found that a key autophagic marker, Beclin1, is indeed decreased in Q84/Q84 mice, consistent with reports in other SCA3 disease models and human disease brain. We did not, however, observe further reductions in Beclin1 with ASO-5 treatment, suggesting that inadvertent disruption of autophagy is not likely to occur with ASO-mediated reduction of ATXN3. In fact, reducing mutATXN3 prevented the accumulation of p62-positive intranuclear puncta in pontine neurons of Q84/Q84 mice, implying that ASO-5 rescues localization of at least one selective autophagy protein following sustained mutATXN3 suppression in vivo. We investigated only these two markers of autophagy, which have been shown to be altered in SCA339,41,42, to assess for potential rescue or exacerbation of autophagy following ASO treatment. Future studies are needed to clarify the role of ATXN3 in autophagy both in healthy and diseased brain.

A limitation of this study is that we did not extend the treatment and evaluation beyond 29 weeks, and thus have not established whether ASO-5 treatment can prolong life in Q84/Q84 mice, which are reported to have early lethality16. The basis for early lethality in this mouse model as well as the human disease is uncertain. Selective vulnerability to vital brainstem nuclei and DCN likely contributes to early lethality in SCA33. In this light, the evidence presented here for robust silencing of mutant ATXN3 in the brainstem and DCN is encouraging.

As demonstrated by FDA approval in 2016 of the first CNS-targeted ASO therapy for treatment of infantile onset spinal muscular atrophy, ASO-mediated transcriptional repression holds promise as a potential therapy for many fatal, as yet untreatable, neurodegenerative diseases. In addition to the current preclinical longitudinal study, ASO preclinical development has been completed for several other polyglutamine diseases, with sustained ASO-mediated phenotypic rescue similarly reported20,22,49,50. Notably, the very ASO assessed here, ASO-5, possesses the same ASO chemistry as a therapeutic approach that has already progressed into early stage clinical trials for the treatment of HD. Although we tested the efficacy of only this single ASO targeting human ATXN3, our preclinical assessment in a progressive disease model expressing the actual human target gene provides proof-of-principle efficacy and safety to justify further efforts to identify ASO candidates for human SCA3 therapy.

Acknowledgments

Ionis Pharmaceuticals identified and generated the anti-ATXN3 ASOs. This work was supported in part by a research contract from Ionis Pharmaceuticals (to H.L.P.), a Michigan Brain Initiative Predoctoral Fellowship for Neuroscience (to L.R.M.), a Becky Babcox Fund Pilot Research Award (G015616 to H.S.M.), research funds from the SCA Network of Sweden, and grants from the NIH (T32-NS007222-33 to H.S.M. and R01-NS038712 to PI H.L.P.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

H.S.M., L.R.M., R.C., H.Z., H.B.Z., V.G.S., and H.L.P conceptualized and designed the study. H.S.M., L.R.M., R.C., R.K., M.M., and K.G.B. acquired and analyzed the data. H.S.M., L.R.M., R.C., and H.L.P. drafted the text and prepared the figures.

Potential Conflicts of Interest:

Ionis Pharmaceuticals solely owns Intellectual Property directed to SCA3 ASOs. H.Z. and H.B.K. are employees of Ionis Pharmaceuticals. This work was supported in part by Ionis Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.do Costa MC, Paulson HL. Toward understanding Machado-Joseph disease. Progress in neurobiology. 2012;97:239–257. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monin ML, et al. Survival and severity in dominant cerebellar ataxias. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2015;2:202–207. doi: 10.1002/acn3.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rub U, et al. Clinical features, neurogenetics and neuropathology of the polyglutamine spinocerebellar ataxias type 1, 2, 3, 6 and 7. Progress in neurobiology. 2013;104:38–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenberg RN. Machado-Joseph disease: an autosomal dominant motor system degeneration. Mov Disord. 1992;7:193–203. doi: 10.1002/mds.870070302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paulson HL, Shakkottai VG, Clark HB, Orr HT. Polyglutamine spinocerebellar ataxias - from genes to potential treatments. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18:613–626. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2017.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramani BPB, Moore LR, Wang B, Huang R, Guan Y, Paulson HL. Comparison of spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 mouse models identifies early gain-of-function, cell-autonomous transcriptional changes in oligodendrocytes. Human Molecular Genetics. 2017 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Schmitt I, et al. Inactivation of the mouse Atxn3 (ataxin-3) gene increases protein ubiquitination. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2007;362:734–739. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cerritelli SM, Crouch RJ. Ribonuclease H: the enzymes in eukaryotes. FEBS J. 2009;276:1494–1505. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiriboga CA, et al. Results from a phase 1 study of nusinersen (ISIS-SMN(Rx)) in children with spinal muscular atrophy. Neurology. 2016;86:890–897. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett CF, Swayze EE. RNA targeting therapeutics: molecular mechanisms of antisense oligonucleotides as a therapeutic platform. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:259–293. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu RZ, et al. Tissue disposition of 2′-O-(2-methoxy) ethyl modified antisense oligonucleotides in monkeys. J Pharm Sci. 2004;93:48–59. doi: 10.1002/jps.10473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finkel RS, et al. Treatment of infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy with nusinersen: a phase 2, open-label, dose-escalation study. Lancet. 2016;388:3017–3026. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31408-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finkel RS, et al. Nusinersen versus Sham Control in Infantile-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1723–1732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alves S, et al. Allele-specific RNA silencing of mutant ataxin-3 mediates neuroprotection in a rat model of Machado-Joseph disease. PloS one. 2008;3:e3341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nobrega C, et al. Silencing mutant ataxin-3 rescues motor deficits and neuropathology in Machado-Joseph disease transgenic mice. PloS one. 2013;8:e52396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.do Costa MC, et al. Toward RNAi therapy for the polyglutamine disease Machado-Joseph disease. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2013;21:1898–1908. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evers MM, et al. Ataxin-3 protein modification as a treatment strategy for spinocerebellar ataxia type 3: removal of the CAG containing exon. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;58:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toonen LJA, Rigo F, van Attikum H, van Roon-Mom WMC. Antisense Oligonucleotide-Mediated Removal of the Polyglutamine Repeat in Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 3 Mice. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2017;8:232–242. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore LR, et al. Evaluation of Antisense Oligonucleotides Targeting ATXN3 in SCA3 Mouse Models. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2017;7:200–210. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kordasiewicz HB, et al. Sustained therapeutic reversal of Huntington’s disease by transient repression of huntingtin synthesis. Neuron. 2012;74:1031–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Passini MA, et al. Antisense oligonucleotides delivered to the mouse CNS ameliorate symptoms of severe spinal muscular atrophy. Science translational medicine. 2011;3:72ra18. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scoles DR, et al. Antisense oligonucleotide therapy for spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. Nature. 2017;544:362–366. doi: 10.1038/nature22044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheruvallath ZS, Kumar RK, Rentel C, Cole DL, Ravikumar VT. Solid phase synthesis of phosphorothioate oligonucleotides utilizing diethyldithiocarbonate disulfide (DDD) as an efficient sulfur transfer reagent. Nucleosides, nucleotides & nucleic acids. 2003;22:461–468. doi: 10.1081/NCN-120022050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKay RA, et al. Characterization of a potent and specific class of antisense oligonucleotide inhibitor of human protein kinase C-alpha expression. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:1715–1722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shakkottai VG, et al. Early changes in cerebellar physiology accompany motor dysfunction in the polyglutamine disease spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. J Neurosci. 2011;31:13002–13014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2789-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Telgkamp P, Raman IM. Depression of inhibitory synaptic transmission between Purkinje cells and neurons of the cerebellar nuclei. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8447–8457. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08447.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cemal CK, et al. YAC transgenic mice carrying pathological alleles of the MJD1 locus exhibit a mild and slowly progressive cerebellar deficit. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1075–1094. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.9.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seidel K, et al. On the distribution of intranuclear and cytoplasmic aggregates in the brainstem of patients with spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 and 3. Brain Pathol. 2017;27:345–355. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seidel K, et al. Brain pathology of spinocerebellar ataxias. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1000-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evert BO, et al. Inflammatory genes are upregulated in expanded ataxin-3-expressing cell lines and spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 brains. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5389–5396. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05389.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schoch KM, Miller TM. Antisense Oligonucleotides: Translation from Mouse Models to Human Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neuron. 2017;94:1056–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bichelmeier U, et al. Nuclear localization of ataxin-3 is required for the manifestation of symptoms in SCA3: in vivo evidence. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7418–7428. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4540-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raman IM, Bean BP. Ionic currents underlying spontaneous action potentials in isolated cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1663–1674. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-05-01663.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dell’Orco JM, Pulst SM, Shakkottai VG. Potassium channel dysfunction underlies Purkinje neuron spiking abnormalities in spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26:3935–3945. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dell’Orco JM, et al. Neuronal Atrophy Early in Degenerative Ataxia Is a Compensatory Mechanism to Regulate Membrane Excitability. J Neurosci. 2015;35:11292–11307. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1357-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mark MD, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 protein aggregates cause deficits in motor learning and cerebellar plasticity. J Neurosci. 2015;35:8882–8895. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0891-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jimenez-Sanchez M, Thomson F, Zavodszky E, Rubinsztein DC. Autophagy and polyglutamine diseases. Progress in neurobiology. 2012;97:67–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong E, Cuervo AM. Autophagy gone awry in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:805–811. doi: 10.1038/nn.2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashkenazi A, et al. Polyglutamine tracts regulate beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Nature. 2017;545:108–111. doi: 10.1038/nature22078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nascimento-Ferreira I, et al. Beclin 1 mitigates motor and neuropathological deficits in genetic mouse models of Machado-Joseph disease. Brain. 2013;136:2173–2188. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sittler A, et al. Deregulation of autophagy in postmortem brains of Machado-Joseph disease patients. Neuropathology. 2017 doi: 10.1111/neup.12433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saitoh Y, et al. p62 plays a protective role in the autophagic degradation of polyglutamine protein oligomers in polyglutamine disease model flies. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2015;290:1442–1453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.590281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Switonski PM, Szlachcic WJ, Krzyzosiak WJ, Figiel M. A new humanized ataxin-3 knock-in mouse model combines the genetic features, pathogenesis of neurons and glia and late disease onset of SCA3/MJD. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;73:174–188. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hansen ST, Meera P, Otis TS, Pulst SM. Changes in Purkinje cell firing and gene expression precede behavioral pathology in a mouse model of SCA2. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:271–283. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akemann W, Knopfel T. Interaction of Kv3 potassium channels and resurgent sodium current influences the rate of spontaneous firing of Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4602–4612. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5204-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hourez R, et al. Aminopyridines correct early dysfunction and delay neurodegeneration in a mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. J Neurosci. 2011;31:11795–11807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0905-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rubinsztein DC. The roles of intracellular protein-degradation pathways in neurodegeneration. Nature. 2006;443:780–786. doi: 10.1038/nature05291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Puorro G, et al. Peripheral markers of autophagy in polyglutamine diseases. Neurol Sci. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s10072-017-3156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lieberman AP, et al. Peripheral androgen receptor gene suppression rescues disease in mouse models of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. Cell Rep. 2014;7:774–784. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sahashi K, et al. Silencing neuronal mutant androgen receptor in a mouse model of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:5985–5994. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]