Abstract

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) rates in African-Americans are more than twice national rates, and historically, African-American parents are more likely than other groups to place infants prone, even when they are aware of supine sleep recommendations. Prior studies have shown African-Americans have low self-efficacy against SIDS but high self-efficacy against suffocation. This study aimed to determine the impact of a specific health message about suffocation prevention on African-American parental decisions regarding infant sleep position. We conducted a randomized controlled trial of 1194 African-American mothers, who were randomized to receive standard messages about safe sleep practices to reduce the risk of SIDS, or enhanced messages about safe sleep practices to prevent SIDS and suffocation. Mothers were interviewed about knowledge and attitude, self-efficacy and current infant care practices when infants were 2–3 weeks, 2–3 months and 5–6 months old. Analyses of covariance were conducted to estimate the change in knowledge, attitudes and practice in each group, and chi square tests were used to compare sleep position with each variable. Over the first 6 months, the proportion of African-American infants placed supine gradually decreased and was unchanged by enhanced education about SIDS, suffocation risk and sleep safety. While initially high self-efficacy against SIDS and suffocation correlated with supine positioning, by 5–6 months self-efficacy did not correspond to sleep position in either group.

SIDS (ICD-10 R95) and other sleep-related deaths, such as accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed (ICD-10 W75) and ill-defined causes of death (ICD-10 R99), account for more than 3600 U.S. deaths annually.[1] There continue to be significant racial disparities in these deaths, with Non-Hispanic black infants having both SIDS and accidental suffocation rates that were approximately twice that of White, non-Hispanic infants at 0.79/1000 live births (vs. 0.32/1000 live births), and 0.45/1000 live births (vs. 0.19/1000 live births), respectively, in 2015.[1] Although biologic differences may affect risk, African-Americans are also twice as likely to place their infants prone for sleep,[2] a practice that is associated with increased risk of sleep-related deaths.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended that infants be placed only supine for every sleep since 2000,[3, 4] because both the prone and side sleep positions, compared with supine positioning, place infants at increased risk for SIDS(OR 2.3–13.1)[5–9]. However, even when they are aware of recommendations to use the supine position, African American parents are more likely than parents of other racial/ethnic groups to place infants prone or on the side.[2, 10] The most recent data show that more than half of African-American parents report placing their infants nonsupine,[2, 11, 12] with non-college educated African-Americans being the most likely to do so.[13] Indeed, despite an initial decline in prone positioning after the Back to Sleep campaign was launched in 1994, there has been an upward trend in usual prone positioning in African-Americans, from 20% in 1999–2004 to 38.1% in 2008.[2] Parental decision to place the infant prone is generally driven by one or both of the following concerns: the misconception that the infant is at increased risk for aspiration or choking when in the supine position and/or the belief that the infant sleeps “better” (i.e., longer) when in the prone position.[14–21] The need for the infant to sleep longer may also relate to parental sleep deprivation; when the infant sleeps longer, the parent sleeps longer. In addition, qualitative and quantitative research suggest that African-Americans believe that SIDS is the result of “fate” or “God’s will”[11] and that they therefore have a low degree of self-efficacy (i.e., they do not believe that their actions can make a difference in whether SIDS occurs).[11] This may help to explain why the Back to Sleep campaign has been less successful in changing practices in African-American families than in other racial groups. However, African-American parents view suffocation as being entirely preventable by their own actions.[11] Messages emphasizing suffocation prevention have been effective in decreasing use of soft bedding.[22] It is yet unclear if such messages are more effective in promoting supine positioning.

We therefore conducted a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the impact of specific health messages on parental decisions regarding infant sleep position. We hypothesized that parents receiving an additional message about the prevention of suffocation would report less nonsupine infant sleep positioning than families who only received the standard message about SIDS risk reduction.

Methods

Because data on parental self-efficacy with regards to SIDS and infant suffocation are currently only available about African-Americans[11] and because sleep-related infant deaths occur disproportionately in African-Americans,[1] we conducted a prospective, randomized, controlled trial of English-speaking, self-identified African-American women who had just delivered an infant. Mothers were excluded if their infant had congenital anomalies (e.g., myelomeningocoele) precluding use of supine positioning, was preterm (<36 weeks) at birth, was hospitalized for >1 week, or had ongoing medical problems requiring subspecialty care. Mothers were randomized into 2 groups. While at the birth hospital, the control group received standard messages about AAP-recommended safe sleep practices to reduce the risk of SIDS. The intervention group received enhanced messages about AAP-recommended safe sleep practices, with emphasis on both reducing SIDS risk and preventing suffocation. After written informed consent was obtained, a brief survey asked about baseline knowledge of and attitudes towards safe sleep recommendations, current intent with regards to safe sleep recommendations and demographics, including mother’s age and education, marital status, infant gender, and presence of other adults in the home, including the other parent and any senior caregivers (such as a grandmother), as these variables can impact both risk for SIDS/sleep-related death[23, 24] and infant sleep practices.[25, 26] Mothers then received written and verbal safe sleep information with group-specific terminology.

Research staff, who were blinded to the study group assignments, contacted participants for 3 follow-up telephone interviews: 1) within 2 weeks of the infant’s birth, 2) when the infant was 2–3 months old, and 3) when the infant was 5–6 months old. At each follow-up interview, mothers completed a survey about knowledge of and attitudes towards safe sleep recommendations, degree of self-efficacy with regards to preventing sleep-related death, and current infant care practices. Each family received a developmentally appropriate toy or book at the time of recruitment, $10 gift card at the end of the first and second follow-up interviews, and $50 gift card at the end of the final interview. The institutional review boards of MedStar Washington Hospital Center and Children’s National Medical Center approved this study.

The primary outcome variable was infant sleep position at six months. We asked about positioning during the past week and the night prior to each interview, as asking about both usual (in the past week) and last night practices is typically used in SIDS research to encourage frank disclosure of actual sleep practices when the practice is not consistent with safe sleep recommendations.[5, 27] Responses about usual and last night practices were analyzed separately. Baseline characteristics between groups were expressed as means and frequencies with 95% confidence intervals (CI) to evaluate expected similarities and any differences that would need to be taken into account in multiple variable analyses. Analyses of covariance were conducted to estimate the change in knowledge, attitudes, and practice in the 2 groups, controlling for baseline levels. Longitudinal logistic regression models assessed the post intervention time-averaged group wise differences measured across 3 time points. This model allowed for full use of the repeated assessments to enhance study power and to adjust variance estimates to account for correlation among assessments on the same person.

Our power calculation was based on current prevalence estimates of 60% for supine sleep position.[28] We further estimated a 10% increase in supine placement in the intervention group. We used a longitudinal design, with 3 repeated assessments per person over time, and assumed that the repeated assessments within a person would be correlated at 70%. We estimated that a total sample size of n=638 would achieve statistical power of 90% at a 2-tailed alpha level of 0.05 to detect a time-averaged difference of 10% between groups.[29–31]

Results

Participant Characteristics

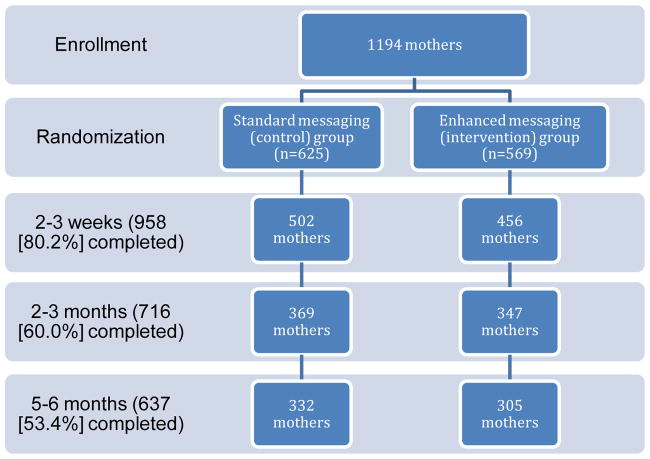

We enrolled 1194 mothers; of these, 958 (80%) completed the first follow-up interview (at mean infant age 12.7 days, range 3–36), 716 completed the second follow-up interview (at mean infant age 82.7 days, range 55–158), and 637 (53.4%) completed the 3 follow-up interviews (Figure 1). Mean infant age at the time of the final interview was 183.6 days (6.1 months). Mean maternal age was 26.4 years (range, 18–43). Seventy-seven percent of mothers were unmarried, >90% had a high school diploma or equivalent, and approximately 56% received WIC and Medicaid benefits. The infant’s father and grandmother lived in half and one-quarter of the homes, respectively (Table 1). Mothers who completed all 3 follow-up interviews were more likely to be ≥30 years of age, to have attended technical/vocational school or a 4 year college, and to have private medical insurance. There were no important demographic differences between the two messaging groups, either at enrollment based on random assignment or time of the final interview despite substantial losses to both groups (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for recruitment, randomization, and study follow-up

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Standard Messaging and Enhanced Messaging Groups at Enrollment and Final Interview

| Characteristic | Enrollment | Final interview | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Standard (n=625) | Enhanced (n=569) | P-value | Standard (n=332) | Enhanced (n=305) | P-value | |

|

| ||||||

| Maternal age | 0.54 | 0.10 | ||||

| 18–24 years | 270(43.2%) | 251(44.1%) | 143(43.1%) | 150(49.2%) | ||

| 25–29 years | 164(26.2%) | 141(24.8%) | 75(22.6%) | 75(24.6%) | ||

| 30–34 years | 113(18.1%) | 98(17.2%) | 64(19.3%) | 38(12.5%) | ||

| ≥ 35 years | 63(10.1%) | 62(10.9%) | 39(11.7%) | 32(10.5%) | ||

| Did not answer | 15(2.4%) | 17(3.0%) | 11(3.3%) | 10(3.3%) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Maternal marital status | 0.36 | 0.75 | ||||

| Married | 121(19.4%) | 119(20.9%) | 69(20.2%) | 64(21.0%) | ||

| Never married | 498(79.7%) | 447(78.6%) | 260(78.9%) | 240(78.7%) | ||

| Divorced/separated | 6(1.0%) | 2(0.4%) | 2(0.6%) | 1(0.3%) | ||

| Widowed | 0(0.0%) | 1(0.2%) | 1(0.3%) | 0(0.0%) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Maternal Education | 0.65 | 0.42 | ||||

| Did not graduate from high school | 70(12.3%) | 79(12.6%) | 34(10.2%) | 42(13.8%) | ||

| Grade 12 (high school graduate)/GED | 232(40.8%) | 234(37.4%) | 132(39.8%) | 122(40.0%) | ||

| Some college/technical/vocational school | 180(31.6%) | 200(32.0%) | 107 (32.2%) | 100(32.8%) | ||

| 4 year college graduate | 87(15.3%) | 112(17.9%) | 59(17.8%) | 41(13.4%) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Infant sex | 0.62 | 0.28 | ||||

| Male | 312(49.9%) | 276(48.5%) | 172(51.8%) | 160(52.5%) | ||

| Female | 313(51.1%) | 293(51.5%) | 160(48.2%) | 145(47.5%) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Receive WIC benefits | 0.50 | |||||

| No | 270(43.2%) | 237(41.7%) | 140(22.0%) | 121(19.0%) | 0.48 | |

| Yes | 355(56.8%) | 331(58.2%) | 192(30.1%) | 183(28.7%) | ||

| Did not respond | 0 | 1(0.2%) | 0(0.0%) | 1(0.2%) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Medical Insurance status | 0.64 | 0.52 | ||||

| Medicaid or no insurance | 386(32.3%) | 356(29.8%) | 210(63.3%) | 187(61.3%) | ||

| Private insurance | 236(19.8%) | 212(17.7%) | 122(36.7%) | 117(38.4%) | ||

| No insurance | 3(0.3%) | 1(0.1%) | 0(0.0%) | 1(0.3%) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Infant’s father lives in home | 318(50.8%) | 270(47.5%) | 0.24 | 174(52.4%) | 163(53.4%) | 0.80 |

|

| ||||||

| Infant’s grandmother lives in home | 176(28.2%) | 171(30.1%) | 0.47 | 98(29.5%) | 85(27.9%) | 0.64 |

|

| ||||||

| Number of people in the household (including infant) (mean) | 4.51 | 4.55 | 0.37 | 4.29 | 4.40 | 0.73 |

|

| ||||||

| Sleep position (usual) | 0.83 | 0.86 | ||||

| Supine (Back) | 590(94.4%) | 530(93.1%) | 263(79.2%) | 246(80.7%) | ||

| Side | 41(6.6%) | 44(7.7%) | 25(7.5%) | 20(6.6%) | ||

| Prone (Stomach) | 12(1.9%) | 10(1.8%) | 44(13.2%) | 39(12.8%) | ||

| Did not respond | 5(0.8%) | 2(0.4%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Sleep position (last night) | n/a | n/a | ||||

| Supine (Back) | 268(80.7%) | 241(79.0%) | 0.85 | |||

| Side | 26(7.8%) | 27(8.8%) | ||||

| Prone (Stomach) | 38(11.4%) | 37(12.1%) | ||||

| Did not respond | ||||||

Sleep position over time, and impact of health messaging on sleep position

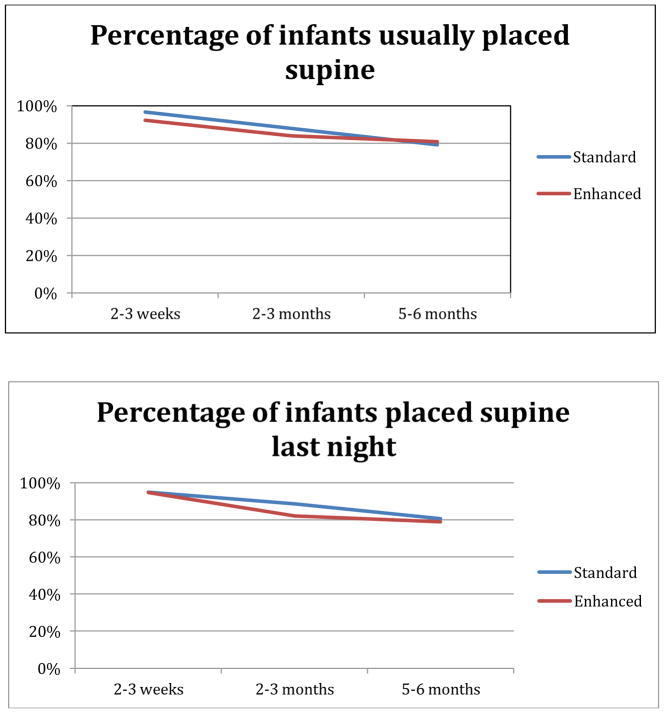

Infant sleep position, both usual and last night, changed over time, with rates of supine placement declining with age in all groups (Figure 2). Infant sleep position was not associated with maternal age or education level, infant gender or breastfeeding status. At baseline (before hospital discharge), having Medicaid insurance was associated with non-supine placement of the infant (p=0.05). However, medical insurance status was not significantly associated with sleep position at older ages.

Figure 2.

Sleep position, usual and last night, in the standard and enhanced messaging groups

Assignment to standard or enhanced messaging group did not impact sleep position. Throughout the first 6 months, infants in both messaging groups were more likely to sleep supine than in any other position. At 2–3 weeks, 95.9% of infants were placed supine for sleep. This declined to 85.8% and then 79.9% at 2–3 months and 5–6 months, respectively. Although the decline in supine positioning over time, both last night and usually, was statistically significant (p<0.001), it was not altered by enhanced messaging (p=0.46 usual; p=0.15 last night) (Table 2). The average groupwise difference overall or at any time point never approached the targeted 10% absolute difference envisioned when the study was powered.

Table 2.

Longitudinal logistic regression model*, with odds ratios for group assignment and infant age

| 2–3 weeks of

age (N=958) |

2–3 months of

age (N=716) |

5–6 months of

age (N=637) |

Group (standard vs enhanced) |

Infant age | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Standard (N=502) |

Enhanced (N=456) |

Standard (N=369) |

Enhanced (N=347) |

Standard (N=332) |

Enhanced (N=305) |

aOR (95% CI) |

p- valu e |

aOR (95% CI) |

p- value |

|

|

| ||||||||||

| Usual Sleep Position | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Back | 482 (96.6%) | 433(92.2 %) | 324(87.8 %) | 291(83.9 %) | 263(79.2 %) | 246(80.7 %) | 1.15 (0.79, 1.69) | 0.46 | 1.01 (1.010, 1.016) | <0.001 |

| Side | 11(2.2%) | 17(3.7%) | 22(6.0%) | 21(6.0%) | 25(7.5%) | 20(6.6%) | ||||

| Prone | 6(1.2%) | 5(1.1%) | 23(6.2%) | 35(10.1%) | 44(13.2%) | 39(12.8%) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Sleep position last night | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Back | 473 (95.0%) | 429(94.7 %) | 327(88.6 %) | 285(82.1 %) | 268(80.7 %) | 241(79.0 %) | 1.35 (0.90, 2.02) | 0.15 | 1.01 (1.008, 1.014) | <0.001 |

| Side | 18(3.6%) | 19(4.2%) | 19(5.2%) | 28(8.1%) | 26(7.8%) | 27(8.8%) | ||||

| Prone | 7(1.4%) | 5(1.1%) | 3(0.8%) | 32(9.2%) | 38(11.4%) | 37(12.1%) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Reasons for sleep position last night | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Prevent SIDS | 238 (49.7%) | 202(45.9 %) | 170(47.5 %) | 151(44.2 %) | 150(46.9 %) | 159(52.1 %) | 0.86 (0.68, 1.09) | 0.22 | 1.00 (0.998, 1.00) | 0.47 |

| Prevent suffocation | 132(27.6 %) | 132(30.0 %) | 91(25.4%) | 88(25.7%) | 63(16.7%) | 97(31.8%) | 1.03 (0.82, 1.29) | 0.79 | 0.99 (0.995, 0.998) | <0.001 |

| Afraid of vomiting/choking | 32(6.7%) | 26(5.9%) | 20(5.6%) | 38(5.3%) | 11(3.4%) | 15(4.9%) | 1.05 (0.71, 1.55) | 0.79 | 0.99 (0.988, 0.993) | <0.001 |

| Baby likes/sleeps better | 34(7.1%) | 33(7.5%) | 52(14.5%) | 60(17.5%) | 75(23.4%) | 85(27.9%) | 1.20 (0.99, 1.64) | 0.24 | 1.01 (1.005, 1.009) | <0.001 |

| Somebody suggested it | 25 (5.2%) | 27(6.1%) | 11(3.1%) | 7(2.0%) | 6(1.9%) | 4(1.3%) | 0.97(0.62, 1.50) | 0.89 | 0.99 (0.986, 0.994) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Belief that sleeping prone increases SIDS risk | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Definitely no or doubtful | 44 (8.7%) | 39 (8.6%) | 59 (16.0%) | 40 (11.5%) | 84 (25.4%) | 64 (21.0%) | 1.01 (0.71, 1.42) | 0.98 | 0.992 (0.990, 0.994) | <0.001 |

| Unsure | 36(7.2%) | 23(5.1%) | 20(5.4%) | 14(14.0%) | 15(4.5%) | 15(4.6%) | ||||

| Possibly or definitely yes | 428 (84.3%) | 392 (86.3%) | 290 (78.6%) | 293 (84.4%) | 232 (70.1%) | 226 (74.1%) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Belief that sleeping prone increases suffocation risk | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Definitely no or doubtful | 22 (4.4%) | 12 (2.6%) | 28 (7.6%) | 27 (7.8%) | 53 (16.0%) | 39 (12.8%) | 1.19 (0.95, 1.49) | 0.12 | 0.993 (0.991, 0.994) | <0.001 |

| Unsure | 7(1.4%) | 6(1.3%) | 6(1.6%) | 3(0.9%) | 4(1.2%) | 6(2.0%) | ||||

| Possibly or definitely yes | 469 (94.2%) | 436 (96.0%) | 335 (90.8%) | 316 (91.3%) | 274 (82.8%) | 259 (85.2%) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||

| What things do you do to protect your baby from SIDS? | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Place baby on back | 422(84.1 %) | 372(81.6 %) | 289(78.3 %) | 242(69.7 %) | 227(68.4 %) | 208(68.2 %) | 0.79 (0.60, 1.05) | 0.11 | 0.994 (0.993, 0.996) | <0.001 |

| Place baby on side | 14(2.8%) | 22(4.8%) | 23(6.2%) | 23(6.3%) | 27(8.1%) | 14(4.6%) | 1.84 (0.93, 3.65) | 0.08 | 1.005 (1.003, 1.011) | 0.013 |

|

| ||||||||||

| What things do you do to protect your baby from suffocation? | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Place baby on back | 407(81.1 %) | 354(77.6 %) | 280(75.9 %) | 235(67.7 %) | 223(67.2 %) | 197(64.6 %) | 0.76 (0.59, 0.99) | 0.04 | 0.996 (0.994, 0.997) | <0.001 |

| Place baby on side | 12(2.4%) | 13(2.8%) | 17(4.6%) | 20(5.8%) | 24(7.2%) | 15(4.9%) | 0.98 (0.59, 1,65) | 0.95 | 1.005 (1.003, 1.009) | 0.001 |

Controlling for baseline sleep position, feeding mode, WIC status, and educational status

Knowledge and Beliefs about Sleep Position

Despite this decline in supine positioning over time, parental knowledge of recommended sleep position was high. When their infants were 2–3 weeks old, all but 6% of women were aware that supine positioning was recommended for infants, and mothers who believed that the recommended sleep position was back only, side or back, and those who were unsure of the recommended position were all more likely to put infants on their back to sleep last week and last night (p<0.0001). Mothers who believed that the side was the only recommended sleep position were more likely to put their infant on their back in the last week and on their side last night. One percent of mothers who believed that supine was the only recommended sleep position placed their infant prone both last week and last night.

Reasons for infant positioning

The most commonly cited reasons for infant positioning were SIDS prevention, suffocation prevention, fear of vomiting/choking, and perceived infant preference (“baby likes” or “baby sleeps better”), and there was no difference between intervention groups (Table 2). However, there were differences as the infant got older. Throughout the first 6 months of their infant’s life, approximately half of parents cited SIDS prevention as a reason for positioning their infant, while one-quarter positioned infants to prevent suffocation. As infants grew older, fewer mothers cited suffocation prevention and concern for vomiting and choking as reasons for infant positioning (p<0.001) but more mothers were concerned about infant preference (p<0.001). Mothers were more likely to place their infant supine both usually and last night at all time points if they cited SIDS prevention, suffocation prevention, or infant preference as reasons, irrespective of the messaging received. However, when the infant was 2–3 weeks old, mothers who cited concern for vomiting/choking were more likely to place infants supine usually (p=0.03) but not more likely to place infants supine last night (p=0.94). By 2–3 months of age, coincident with declining maternal concern about vomiting/choking, these infants were consistently more likely to be placed supine.

There was less consistency with positioning with respect to maternal beliefs about the “best way to sleep.” Mothers who positioned their infants to prevent SIDS were consistently (i.e., at all time points) more likely to believe the best way to sleep was in the supine position, regardless of the messaging they received. Those who positioned their infants to prevent suffocation, to make infants sleep better and because they were afraid of vomiting/choking did not consistently place their infants supine through the study period. However, greater than 90% of mothers in both intervention groups at all three time points believed that the best position for their infant was supine.

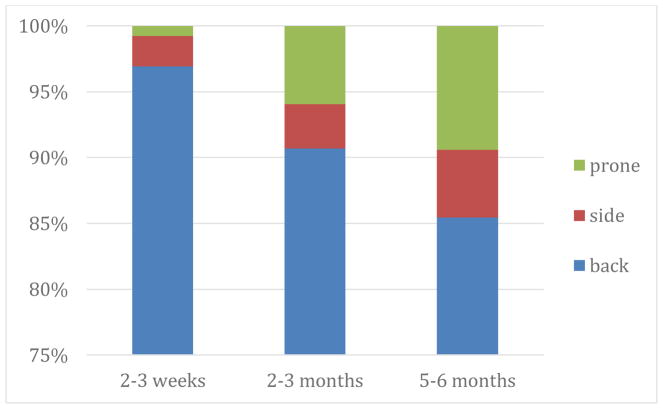

While mothers who believed that infant position increased the risk of both SIDS and suffocation were more likely to place infants supine throughout the first six months, as infants grew older, fewer believed that prone positioning increased the risk for SIDS (p<0.001) or suffocation (p<0.001). This was not impacted by the messaging received. High self-efficacy against SIDS and suffocation also affected positioning less as infants grew older (see Figure 3). Although high self-efficacy against both SIDS and suffocation was associated with increased supine positioning in both groups at 2–3 weeks (p<0.001), by 5–6 months it was not correlated in either messaging group.

Figure 3.

Usual sleep position of infants whose mothers had high self-efficacy against SIDS

When mothers were asked about the specific actions taken against both SIDS and suffocation, mothers who stated that they placed their infants on the side as a preventive measure were both more likely to place their infant supine at 2–3 weeks, regardless of the intervention group. Also regardless of intervention group, these mothers were more likely to place their infants on the side at 2–3 months and 5–6 months (p<0.0001). In addition, the intervention group did not impact whether mothers stated that they placed infants supine to prevent SIDS or suffocation. However, as infants grew older, mothers were less likely to state that they placed infants supine to prevent SIDS (p<0.001) or suffocation (p<0.001), but were more likely to state that they placed infants on the side to prevent SIDS (p=0.013) or suffocation (p=0.001).

Socioeconomic Status and Sleep Position

Throughout the study period sleep position was not altered by socioeconomic status. There was no significant difference in supine vs. nonsupine sleeping either usually or last night when comparing those with Medicaid/no insurance to those with commercial insurance, or when comparing those who received WIC to those who did not receive WIC at all three time points (all p>0.124).

The Influence of Others on Sleep Position

At the baseline survey and 2–3 week follow up when >90% of women chose the supine position, mothers were more likely to place their infants supine if a nurse had discussed sleep position with them (p=0.02). In contrast, at baseline, mothers were more likely to choose prone if they had discussed sleep position with the infant’s father (p=0.04). As the infant became older, the influence of both nurses and the infant’s father became non-significant, while the influence of friends became increasingly significant. Further, mothers were more likely to place their infants prone at 2–3 months (p=0.025) and 5–6 months (p<0.001) if they had discussed sleep position with friends.

Discussion

In this randomized controlled trial of health messaging targeting African-American mothers, we found that receipt of an enhanced message about SIDS risk reduction and suffocation prevention did not affect parental practices regarding infant sleep positioning. Rates of supine positioning were not statistically different in the two groups. Reasons for positioning and influences on decisions regarding position changed with time.

Consistent with prior studies, our data demonstrate the effectiveness of public health campaigns such as Back to Sleep, as 94% of the African-American mothers who participated in this study knew that the recommended sleep position was supine. Some may have been placing their infants supine without knowing why they were doing so. However, as infants grew older, there was a gradual but significant increase in infants being placed on the side and in the prone position, and receiving enhanced messaging did not alter this. This change was particularly concerning because much of it was occurred between 1 and 4 months of age, which is the period of highest SIDS risk.[32] Further, the risk of SIDS is exceptionally high in unaccustomed prone infants, those who are typically placed supine but are newly placed prone, either by a caregiver or by rolling from the side position.[33] Thus, altering the typical position to either side or supine lying between 2 and 3 weeks and 2 and 3 months is troubling.

Given the small number of infants who were placed in unsafe sleep positions in the baseline control group, it is perhaps not surprising that enhanced messaging did not create any statistically significant changes in position through the first follow-up at 2–3 weeks. The fact that it did not in any way alter the gradual decrease in the proportion of African-American infants placed supine over the first 6 months was however unexpected. The failure of education geared more towards avoiding suffocation than SIDS to alter behaviors and beliefs may indicate that data showing African Americans are more concerned about suffocation than SIDS[11] in newborns is no longer accurate, that this concern is not sufficient to change behavior, or that this concern is outweighed by the fear of aspiration when supine. Future qualitative and quantitative studies are needed to elucidate this. However, our data also indicate that as infants aged, maternal self-efficacy against both SIDS and suffocation ceased to correlate with sleep positioning, which may indicate that educational campaigns that aim to empower parents to prevent SIDS and other sleep related deaths may not be sufficient to reinforce supine sleeping in older infants. The decreasing effect of maternal self-efficacy as infants grow older may be the result of experience. As mothers become increasingly comfortable with their infants, they may become more comfortable with the risk or their own infant’s ability to avoid this risk. Perceived social norms and pressures from friends and family members may also play a role in the change in position.[34] The fact that this change in position begins to occur by 2–3 months rather than only at 5–6 months makes it unlikely to correlate with the ability of infants to roll from supine to prone (which usually occurs at approximately 4 months). This is also reflected in the observations that maternal belief that prone position increases the infant’s risk of SIDS or suffocation declines as the infant becomes older; mothers also are more likely to cite infant preference as a reason for positioning as the infant is older.

We also found a shift in trusted sources for mothers during this same time period. Mothers who cited the nurse as a trusted source in the newborn period were more likely to choose the supine position. However, by the time that the infant was 2–3 months of age, friends became significant as trusted sources. It is possible that, when the mother and infant are both experiencing new difficulties, such as colic, that may make it more difficult for the infant to sleep, mothers may become frustrated and look to alternative sources for advice. Further, we found that pediatrician advice did not significantly affect sleep position decisions. This is consistent with a qualitative study that found that parents seek information from multiple sources and are comfortable making decisions against the advice of their pediatricians.[21] The increased reliance on friends’ advice is particularly concerning because those who rely on their advice were more likely to place infants prone.

We acknowledge the limitations of our study. First, our study recruited mothers from a single geographic area, and the participants were less likely to attend college, more likely to be unmarried and more likely to have Medicaid health insurance than has been reported in national surveys of African-American women.[35] We also acknowledge that numbers of mothers who reported nonsupine positioning were small, and this may have introduced sampling bias. In addition, despite concerted and repeated efforts to contact mothers for follow-up interviews, our attrition rate over 6 months was 47%. While our recruitment targets accounted for potentially high attrition rates, mothers completing all interviews were demographically different than those who did not complete the interviews, in that they were older, better educated, and more likely to have private insurance. Prior studies have shown these mothers are demographically less likely to place infants prone,[5, 6, 28] raising concern that this attrition rate may have skewed our results and somewhat affecting generalizability. However, the fact that we found no difference in supine vs. nonsupine positioning with relation to socioeconomic status markers at any of the three time points, and the lack of difference in demographic characteristics of mothers in the 2 intervention groups at study enrollment and the last interview suggests that our results are not the result of selection bias. Further, there were no highly publicized infant deaths during the data collection period that might have impacted on our results. The NICHD Safe to Sleep campaign, which supersedes the Back to Sleep campaign and which includes strategies to prevent other sleep-related causes of infant death, including accidental suffocation and strangulation, began in late 2012. However, we do not believe that the campaign impacted our results, as there were no widely publicized public service announcements or brochures distributed, and any impact would have been seen equally in the two groups. Finally, we acknowledge limitations inherent in parental reporting. We did not directly observe sleep practices, and mothers may have been reluctant to admit to nonsupine positioning, thus leading to an overestimate of supine positioning. In addition, there is potential for a social desirability bias, as mothers receiving the enhanced message may have had a different reporting tendency compared to the mothers receiving the standard message. Maternal willingness to be forthcoming about actual practices may also have been impacted by questions about self-efficacy. However, if any of these factors had impacted on our results, we would have anticipated that mothers in the enhanced message group were less likely to report nonsupine positioning. However, our sleep position rates were comparable to those seen for African-Americans in other surveys,[28] and so we believe that these responses are fairly representative of the general African-American population.

As we consider further efforts to reduce the risk of SIDS in high risk groups, specifically African Americans, our data support the need for further efforts to target parents when infants are between 1 and 4 months of age, when SIDS rates are highest. The educational campaigns should focus on the additional risks of the unaccustomed prone position and should be targeted at parents, additional caregivers who may be placing infants in new positions during this period, and those who are providing advice to parents. Ideally, these campaigns would begin before the child was born, as part of prenatal care and parenting classes. Given that we have shown that as infants get older, self-efficacy against SIDS and suffocation stop corresponding to infant positioning, focusing efforts on teaching the increased risk up to 4 months, may help to reverse that trend.

Conclusion

While the vast majority of mothers are aware of and plan to follow safe sleep recommendations, there are many factors which contribute to the change in sleep position over the first 6 months of life. One such factor is the belief that the infant sleeps better when in the prone position, resulting in an increased percentage of mothers choosing the prone position. Further, at approximately 2–3 months infant age, mothers are beginning to place their infants prone more frequently, and this is coincident with the increasing influence of the advice from friends as opposed to healthcare professionals. Further work, focusing on infant sleep position and the increased risk of positional change between 1 and 4 months, when the risk for SIDS is highest, is needed. In addition, outreach and education regarding safe infant sleep practices must not be limited to parents.

Acknowledgments

Research Support: This project was supported by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources Service Administration 1R40MC21511 and the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities P20MD000198.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.United States Department of Health and Human Services (US DHHS), Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), Office of Analysis and Epidemiology (OAE), Division of Vital Statistics (DVS) [Accessed March 9 2018];Linked Birth /Infant Death Records on CDC WONDER Online Database. http://wonder.cdc.gov/lbd.html.

- 2. [Accessed March 12 2018];National Infant Sleep Position study website. http://slone-web2.bu.edu/ChimeNisp/Main_Nisp.asp.

- 3.Moon RY. Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: updated 2016 recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20162938. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kattwinkel J, Brooks J, Keenan ME, Malloy MH. Changing concepts of sudden infant death syndrome: implications for infant sleeping environment and sleep position. American Academy of Pediatrics. Task Force on Infant Sleep Position and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Pediatrics. 2000;105(3 Pt 1):650–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.3.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hauck FR, Herman SM, Donovan M, et al. Sleep environment and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome in an urban population: the Chicago Infant Mortality Study. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 Part 2):1207–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li DK, Petitti DB, Willinger M, et al. Infant sleeping position and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome in California, 1997–2000. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(5):446–55. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blair PS, Fleming PJ, Smith IJ, et al. Babies sleeping with parents: case-control study of factors influencing the risk of the sudden infant death syndrome. CESDI SUDI research group. BMJ. 1999;319(7223):1457–62. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleming PJ, Blair PS, Bacon C, et al. Environment of infants during sleep and risk of the sudden infant death syndrome: results of 1993–5 case-control study for confidential inquiry into stillbirths and deaths in infancy. Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths Regional Coordinators and Researchers. BMJ. 1996;313(7051):191–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7051.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpenter RG, Irgens LM, Blair PS, et al. Sudden unexplained infant death in 20 regions in Europe: case control study. Lancet. 2004;363:185–91. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasinski KA, Kuby A, Bzdusek SA, Silvestri JM, Weese-Mayer DE. Effect of a sudden infant death syndrome risk reduction education program on risk factor compliance and information sources in primarily black urban communities. Pediatrics. 2003;111(4 Pt 1):e347–54. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.e347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moon RY, Oden RP, Joyner BL, Ajao TI. Qualitative analysis of beliefs and perceptions about sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) among African-American mothers: Implications for safe sleep recommendations. J Pediatr. 2010;157(1):92–7e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.01.027. S0022-3476(10)00042-9 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PRAMStat. Atlanta, GA: [Accessed July 18 2017]. https://www.cdc.gov/prams/pramstat/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corwin MJ, Lesko SM, Heeren T, et al. Secular changes in sleep position during infancy: 1995–1998. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):52–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colson ER, McCabe LK, Fox K, et al. Barriers to Following the Back-to-Sleep Recommendations: Insights From Focus Groups With Inner-City Caregivers. Ambul Pediatr. 2005;5(6):349–54. doi: 10.1367/A04-220R1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mosley JM, Stokes SD, Ulmer A. Infant sleep position: discerning knowledge from practice. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(6):573–82. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.6.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moon RY, Omron R. Determinants of infant sleep position in an urban population. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2002;41(8):569–73. doi: 10.1177/000992280204100803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ottolini MC, Davis BE, Patel K, Sachs HC, Gershon NB, Moon RY. Prone infant sleeping despite the "Back to Sleep" campaign. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:512–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.5.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willinger M, Ko C-W, Hoffman HJ, Kessler RC, Corwin MJ. Factors associated with caregivers' choice of infant sleep position, 1994–1998: the National Infant Sleep Position Study. JAMA. 2000;283(16):2135–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.16.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moon RY, Biliter WM. Infant sleep position policies in licensed child care centers after back to sleep campaign. Pediatrics. 2000;106(3):576–80. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.3.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moon RY, Weese-Mayer DE, Silvestri JM. Nighttime child care: inadequate sudden infant death syndrome risk factor knowledge, practice, and policies. Pediatrics. 2003;111(4 Pt 1):795–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oden R, Joyner BL, Ajao TI, Moon R. Factors influencing African-American mothers' decisions about sleep position: a qualitative study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(10):870–80. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30705-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathews A, Joyner BL, Oden RP, He J, McCarter R, Jr, Moon RY. Messaging Affects the Behavior of African American Parents with Regards to Soft Bedding in the Infant Sleep Environment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Pediatr. 2016;175:79–85 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willinger M, Hoffman HJ, Wu K-T, et al. Factors associated with the transition to nonprone sleep positions of infants in the United States: the National Infant Sleep Position Study. JAMA. 1998;280:329–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.4.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muhuri PK, MacDorman MF, Ezzati-Rice TM. Racial differences in leading causes of infant death in the United States. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2004;18(1):51–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brenner R, Simons-Morton BG, Bhaskar B, et al. Prevalence and predictors of the prone sleep position among inner–city infants. JAMA. 1998;280:341–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.4.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brenner RA, Simons-Morton BG, Bhaskar B, Revenis M, Das A, Clemens JD. Infant-parent bed sharing in an inner-city population. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(1):33–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willinger M, Ko CW, Hoffman HJ, Kessler RC, Corwin MJ. Trends in infant bed sharing in the United States, 1993–2000: the National Infant Sleep Position study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(1):43–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colson ER, Rybin D, Smith LA, Colton T, Lister G, Corwin MJ. Trends and factors associated with infant sleeping position: the national infant sleep position study, 1993–2007. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(12):1122–8. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.234. 163/12/1122 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown H, Prescott R. Applied Mixed Models in Medicine. 2. Chichester, West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu H, Wu T. Sample size calculation and power analysis of time-averaged difference. J Mod Appl Stat Meth. 2005;4(2):434–45. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diggle PJ, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moon RY. Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: evidence base for 2016 updated recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20162940. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell EA, Thach BT, Thompson JMD, Williams S. Changing infants' sleep position increases risk of sudden infant death syndrome. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1136–41. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.11.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colson E, Geller NL, Heeren T, Corwin MJ. Factors associated with choice of infant sleep position. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20170596. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed July 19, 2016];2006–2010 American Community Survey. 2012 http://factfinder2.census.gov.