Abstract

Objective

Previous gene expression analysis identified a network of co-expressed genes that is associated with β-amyloid neuropathology and cognitive decline in older adults. The current work targeted influential genes in this network with quantitative proteomics to identify potential novel therapeutic targets.

Methods

Data came from 834 community-based older persons who were followed annually, died and underwent brain autopsy. Uniform structured postmortem evaluations assessed the burden of β-amyloid and other common age-related neuropathologies. Selected reaction monitoring quantified cortical protein abundance of 12 genes prioritized from a molecular network of aging human brain that is implicated in Alzheimer’s dementia. Regression and linear mixed models examined the protein associations with β-amyloid load and other neuropathologic indices as well as cognitive decline over multiple years prior to death.

Results

The average age at death was 88.6 years. 349 participants (41.9%) had Alzheimer’s dementia at death. A higher level of PLXNB1 abundance was associated with more β-amyloid load (p=1.0×10−7) and higher PHFtau tangle density (p=2.3×10−7), and the association of PLXNB1 with cognitive decline is mediated by these known Alzheimer’s disease pathologies. On the other hand, higher IGFBP5, HSPB2, AK4 and lower ITPK1 levels were associated with faster cognitive decline and, unlike PLXNB1, these associations were not fully explained by common neuropathologic indices, suggesting novel mechanisms leading to cognitive decline.

Interpretation

Using targeted proteomics, this work identified cortical proteins involved in Alzheimer’s dementia and begins to dissect two different molecular pathways: one affecting β-amyloid deposition and another affecting resilience without a known pathologic footprint.

INTRODUCTION

While there have been rapid advances in our understanding of the role of age-related neuropathologies in Alzheimer’s dementia, much of its underlying neurobiology remains unclear. Systems biology and network-based approaches have identified novel coexpression networks and gene targets within these networks that are implicated in late onset Alzheimer’s dementia1, 2. Using RNA sequencing (RNAseq) gene expression data from a large sample of postmortem human brains, we previously reported robust relationships between a network of co-expressed cortical genes and the burden of brain β-amyloid deposition, the pathologic hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), as well as decline in cognition, the clinical hallmark of Alzheimer’s dementia3. This group of co-expressed genes, arbitrarily labelled module 109 (m109), represents a cortical transcriptional program that is the most proximal molecular event occurring prior to cognitive decline in aging. Further, our prior modeling suggests that m109 is causally implicated in Alzheimer’s dementia through two independent mechanisms: a minor effect on brain amyloid deposition and a major effect that is independent of β-amyloid and other pathologies3. The m109 consists of 390 genes, and we prioritized 30 unique nodal genes as potential drivers of the network’s biological function. In an initial round of functional validation, we tested 21 of these 30 genes in human astrocytes and/or human neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC). Of the 14 genes examined in vitro using primary human astrocytic cell cultures, INPPL1 and PLXNB1 RNA knockdown reproducibly reduced the production of pathogenic soluble Aβ42. Interestingly, none of the genes were validated following neuronal perturbation. These experiments provided functional validation that the INPPL1 and PLXNB1 genes may play an important role in mediating m109’s effect on β-amyloid metabolism. Much of the variance in cognitive decline explained by m109 remains unexplained after we account for the effect of PLXNB1 and INPPL1, supporting the network finding that some genes in this network influence cognitive decline independent of AD pathology3.

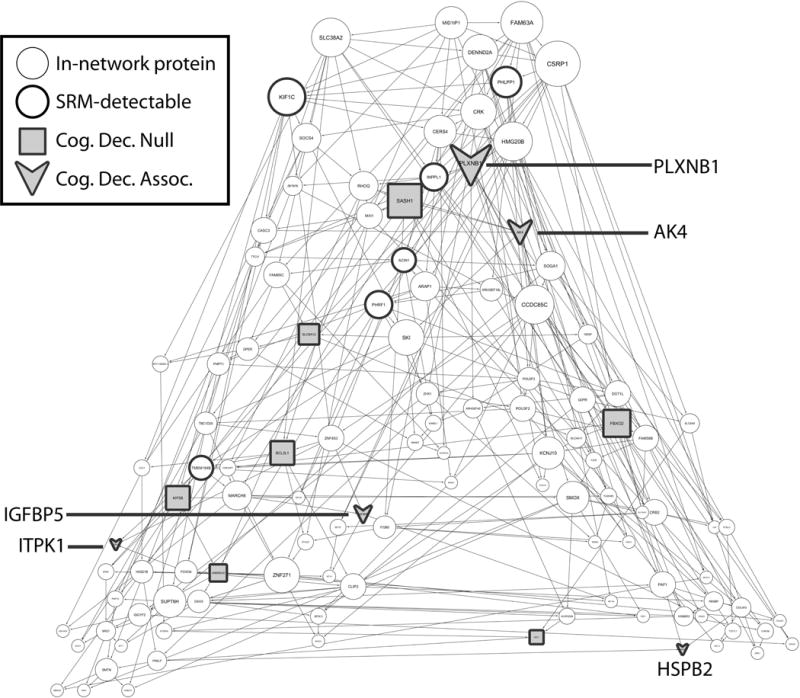

In this study, we used selection reaction monitoring (SRM) quantitative proteomics to quantify protein levels of 12 of the nodal genes within m109 (Figure 1). With these data, we extended our prior findings in two ways. First, we quantified the protein abundance of PLXNB1, our best candidate gene (INPPL1 did not pass quality control), in postmortem human brain, confirmed its relation to β-amyloid at the protein level, and examined its association with other Alzheimer’s pathologic and clinical phenotypes. Second, we quantified 11 additional proteins prioritized within m109 (some of which could not be tested in our in vitro system) to examine their associations with cognitive decline as well as AD and other age-related neuropathologies.

Figure 1.

In-network proteins in module m109. Figure 1 shows selected proteins in m109 network. Nodes with thicker border are proteins (N=18) that are detected in our SRM experiment and shaded nodes (N=12) are those that are quantifiable. Arrows represent proteins that are associated with cognitive decline (N=5), and squares represent those that did not reach the cut-off for a significant association.

METHODS

Study participants

Participants were community based older persons enrolled in two ongoing cohort studies of aging and dementia, the Religious Orders Study (ROS)4 and Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP)5. Both studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Rush University Medical Center. Participants entered the studies without known dementia and agreed to annual assessments as well as brain donation after death. A written informed consent and an anatomical gift act were obtained from each participant.

SRM proteomics was performed at Pacific North National Laboratory (PNNL). Brain samples for distribution to PNNL were identified on November 16, 2012. At that time there were 995 participants who had died and had completed cognitive assessments and neuropathologic evaluation. By mid-January 2016, we had sent the first 834 samples in the interest of time elected to perform the first round of SRM proteomics that included the proteins from m109. The average age at death was 88.6 years (standard deviation [SD]: 6.5; range 65.9-108.3). A majority were female (65.8%) and almost all were non-Latino whites (95.9%). The average years of education was 16.3 (SD: 3.6; range 3-28).

Cognitive assessment and clinical diagnosis

Detailed neuropsychological and clinical examinations were administered each year to participants in both studies6. The overall follow-up rate exceeded 95%. The cognitive battery consists of 17 tests and assesses multiple domains of cognitive ability. To minimize floor or ceiling artifact of individual test, a composite score was used to measure the decline in cognition many years prior to death. Briefly, scores for each test were standardized using baseline means and SDs of both cohorts, and the resulting z-scores were then averaged across the tests to derive the measure of global cognition.

Annual clinical diagnosis was based on the recommendations of the joint working group of the National Institute of Neurologic and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS/ADRDA)7. Results from cognitive assessment and physical examination were reviewed, and a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia was made by a clinician if participant demonstrates progressive worsening of cognition as well as deficit in memory and at least one other cognitive domain8. At the time of death, a summary diagnostic opinion regarding participant’s final cognitive status was provided by a neurologist after reviewing available clinical data9.

Neuropathology measures

Brain autopsy follows standard protocol10. Neuropathologic evaluations, blinded to clinical data, assessed the burden of common age-related neuropathologies, including AD, cerebral infarcts, Lewy bodies, hippocampal sclerosis, TDP-43, cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), atherosclerosis and arteriolosclerosis. Specifically, β-amyloid and PHFtau tangle pathologies were measured in 8 predetermined brain regions using molecular specific immunohistochemistry11. 20μm sections were immunostained with one of three monoclonal antibodies (4G8, 1:9000, Covance Labs, Madison, WI; 6F/3D, 1:50, Dako North America Inc., Carpinteria, CA; and 10D5, 1:600, Elan Pharmaceuticals, San Francisco, CA) for β-amyloid. PHFtau tangles were assessed using an antibody specific for phosphorylated tau: AT8 (1:1,000, Innogenetics, San Ramon, CA). β-amyloid deposition was quantified using image analysis. Percent area positive for β-amyloid within each region was square root transformed and averaged to compute a summary score for β-amyloid load. PHFtau tangles per mm2 were quantified using stereology within each region and then averaged to obtain a summary score for PHTtau tangle density.

Chronic macroscopic infarcts was recorded during gross examination and confirmed histologically12. Presence of microinfarcts were determined in a minimum of 9 regions, identified using haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain13. Lewy bodies in substantial nigra, limbic and neocortical regions was identified using α-synuclein immunostaining14. Hippocampal sclerosis was assessed using H&E stained sections from mid-hippocampus15. TDP-43 staging from amygdala to limbic and neocortical regions were determined using monoclonal TDP-43 antibody16. CAA was assessed in 4 neocortical regions using immunohistochemistry17. β-amyloid depositions in meningeal and parenchymal vessels in each region were rated and averaged across to obtain a summary CAA measure. Severity of atherosclerosis was graded by gross examination of vessels in the circle of Willis, and arteriolosclerosis was graded on H&E stained sections of basal ganglia18.

Targeted SRM proteomics

Targeted proteomics analysis was performed using frozen tissue from dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), the same brain region selected for RNAseq and other omic analysis. The sample preparation for LC-SRM analysis follows standard protocol19, 20. To meet the scale of the study, all the liquid handling steps were performed in 96 well plate format using Epmotion 5075 TMX (Eppendorf) or Liquidator96 (Rainin). An average ~20 mg of brain tissue from each individual was homogenized in denaturation buffer (8M urea, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA). Following denaturation, 400 ug protein aliquots were taken for further alkylation with 40 mM iodoacetamide and digestion with trypsin (1:50 w/w trypsin to protein ratio). The digests were cleaned using solid phase extraction (SPE) using Strata C18-E (55 μm, 70 Å) 25 mg/well 96-well plates (Phenomenex) on positive pressure manifold CEREX96 (SPEware). The SPE protocol is as follows. After thawing the plate the samples were acidified by adding 80 μL of 10% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to achieve final 1% concentration. The wells were washed using gravity flow twice with 600 μL of methanol and once with 600 μL of 0.1% TFA. The samples were loaded onto the SPE plate and allowed to flow through using gravity flow followed by 1 psi positive air pressure. The wells with loaded samples were washed three times with 600 μL of solvent containing 5% acetonitrile and 0.1% TFA. To remove residual washing solvent the well beds were dried with 30 psi flow. Finally the peptides were eluted from C18 beds with 400 μL of solvent containing 80% acetonitrile and 0.1% TFA. After drying down overnight on SpeedVac (Thermo Fisher), the samples were reconstituted in 85 μL or 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 7.8). The peptide concentrations obtained were measured using BCA assay. Tryptic peptide concentrations were readjusted to 1 ug/uL. 30 uL aliquots were mixed with 30 uL synthetic peptides (Supplementary Table 1). For the previously prioritized 30 genes, we selected 55 proteotypic peptides based on reanalysis of comprehensive LC-MS/MS dataset of all human tissues21. The 55 synthetic heavy peptides labeled with 13C/15N on C-terminal lysine or arginine were purchased from New England Peptide (Gardner, MA) with cysteine modification with carbamidomethylation. 27 of the 55 peptides were detected in a few representative brain samples (Supplementary Table 1 Column 4), which were subsequently quantified in the entire sample-set with 79 technical controls. Details on SRM method configuration are reported in Supplementary Table 2.

LC-SRM experiments were performed on a nano ACQUITY UPLC coupled to TSQ Vantage MS instrument, with 2 μL of sample injection for each measurement. A 0.1% FA in water and 0.1% in 90% ACN were used as buffer A and B, respectively. Peptide separations were performed by an ACQUITY UPLC BEH 1.7 μm C18 column (75 μm i.d. × 25 cm) at a flow rate 350 nL/min using gradient of 0.5% of buffer B in 0-14.5 min, 0.5-15% B in 14.5-15.0 min, 15-40% B in 15-30 min and 45-90% B in 30-32 min. The heated capillary temperature and spray voltage was set at 350 °C and 2.4 kV, respectively. Both the Q1 and Q3 were set as 0.7 FWHM. The scan width of 0.002 m/z and a dwell time of 10 ms were used.

The SRM data were analyzed by Skyline software22. All the data were manually inspected to ensure that (1) chromatographic peaks of the endogenous peptides coincide with the standards; (2) shapes of the peaks agree, and (3) orders and ratios of the transition intensities agree between light and heavy isotopes. Transitions interfering with co-eluting peptides were excluded from quantification. Examples of chromatograms from randomly selected samples are shown at https://www.radc.rush.edu/targeted_srm.htm. The peak area ratios of endogenous light peptides and their heavy isotope-labeled internal standards (i.e., L/H peak area ratios) were then automatically calculated by the Skyline software and the transitions without matrix interference was used for accurate quantification.

The reproducibility of the measurements and the quality of peptide quantification were assessed using 79 technical controls. The technical controls came from a pooled sample by mixing an aliquot of each homogenized brain sample. These identical samples were randomly scattered across the plates with a ratio of 8 per plate. Notably, variance across the technical controls is exclusively due to sample processing and instrumental measurements. We consider a peptide signal informative if the variance across the individual brain samples, which includes both technical and biological variances, exceeds 2-fold of technical variance. 9 of 27 detectable peptides did not meet the 2-fold threshold and were excluded (Supplementary Table 1 Column 5). Two peptides (BCL2L1_1 and SLC6A12_1) had the ratios close to 2, but were retained considering reasonably low CV values and convincing chromatographic profiles.

After testing for sensitivity and quality of quantification we retained 18 peptides corresponding to 12 proteins, including AK4, ANKRD40, BCL2L1, FBXO2, HSPB2, IGFBP5, ITPK1, KIF5B, PLXNB1, SASH1, SLC6A12 and VAT1 (Supplementary Table 3). For proteins with multiple peptides quantified, the peptide with the highest signal to noise ratio was used. The peptide relative abundances were log2 transformed and centered at the median.

Statistical analysis

Spearman correlations, t-tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA) described bivariate relationship between demographic, cognitive and neuropathologic measures with targeted protein abundance. Since in vitro model reported that knockdown of the PLXNB1 gene expression reduces β-amyloid, we tested the hypothesis that higher PLXNB1 protein abundance was associated with more severe β-amyloid. To do so, we fit linear regression models with β-amyloid load as the continuous outcome, and PLXNB1 abundance as the predictor. We subsequently examined the protein association with other pathologic and cognitive phenotypes.

To follow up on the effect of m109 overexpression on cognitive decline, we also examined 11 additional prioritized proteins in relation to cognitive decline in a series of linear mixed models. In these models, annual global cognitive scores was the longitudinal continuous outcome; the model predictors included a term for time in years prior to death which estimates the mean rate of cognitive decline (i.e. slope), and a term for the interaction between time and protein abundance which estimates the mean change of cognitive slope with every log2 unit increase in protein abundance. For proteins shown association with cognitive decline, we further examined their relationship with common age-related neuropathologies. Here, each neuropathologic index was the outcome, and linear regression or logistic regression models were used for the hypothesis testing.

Analyses were performed using SAS/STAT® software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Unless otherwise noted, all the models were controlled for demographics and the technical confounder of plate.

RESULTS

Characteristics of study participants

At the time of death, 349 people (41.9%) were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia. The percentage was higher for pathologic diagnosis of AD, where 520 (62.4%) met intermediate or high likelihood for AD according to modified NIA-Reagan criteria23. In addition, a considerable burden of non-AD pathologies was observed (Table 1). Notably, over 50% of these decedents had TDP-43 inclusions, 20% had Lewy bodies and nearly 10% had hippocampal sclerosis. Cerebral vascular diseases were also common. Over a third had macroscopic infarcts and nearly 30% had microinfarcts. Moderate to severe atherosclerosis and arteriolosclerosis were observed in about 40% each, as was moderate to severe CAA.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of study participants

| Variable | Mean, SD |

| Age at death (years) | 88.6, 6.5 |

| Female (n, %) | 549, 65.8% |

| Education (years) | 16.3, 3.6 |

| Non-Latino white (n, %) | 799, 95.9% |

| Length of follow-up (years) | 6.7, 4.1 |

| Clinical AD dementia (n, %) | 349, 41.9% |

| Pathologic diagnosis of AD† (n, %) | 520, 62.4% |

| β-amyloid load | 1.6, 1.2 |

| PHFtau tangle density | 6.2, 7.5 |

| Macroscopic infarcts (n, %) | 299, 35.9% |

| Microinfarcts (n, %) | 239, 28.7% |

| Lewy bodies (n, %) | 181, 21.7% |

| Hippocampal sclerosis (n, %) | 71, 8.6% |

| TDP-43 inclusion (% positive) | |

| None | 352, 48.2% |

| Amygdala only | 133, 18.2% |

| Amygdala and limbic only | 147, 20.1% |

| Amygdala, limbic and neocortex | 98, 13.4% |

| Cerebral amyloid angiopathy | |

| None | 167, 20.5% |

| Mild | 355, 43.5% |

| Moderate | 185, 22.7% |

| Severe | 109, 13.4% |

| Atherosclerosis (n, %) | |

| None | 107, 12.9% |

| Mild | 60, 43.3% |

| Moderate | 280, 33.7% |

| Severe | 84, 10.1% |

| Arteriolar sclerosis (n, %) | |

| None | 212, 25.6% |

| Mild | 299, 36.1% |

| Moderate | 225, 27.2% |

| Severe | 92, 11.1% |

SD: Standard deviation

Intermediate or high likelihood according to modified NIA-Reagan criteria

Overall, we did not observe strong correlations between protein abundance and demographics, with the exception for VAT1 where males had higher VAT1 protein level than females. As expected, PLXNB1 was strongly correlated with β-amyloid and PHFtau tangles. Several proteins, including AK4, FBXO2, HSPB2, IGFBP5, ITPK1 and VAT1, also showed bivariate correlations with AD pathologies. In addition, we observed that the ITPK1 protein level was lower with more advanced staging of TDP-43 inclusions and the IGFBP5 protein level was elevated with the presence of Lewy bodies. There was a lack of correlation between targeted proteins and cerebral infarcts or vessel pathologies.

PLXNB1 and β-amyloid pathology

We first tested the association of PLXNB1 protein abundance with β-amyloid load. Consistent with the finding from our prior in vitro models, higher PLXNB1 abundance was associated with more β-amyloid load (Estimate=0.633, Standard error [SE]=0.118, p=1.0×10−7), as well as more PHFtau tangles (Estimate=0.702, SE=0.135, p=2.3×10−7). The latter association was attenuated by approximately one-half (Estimate=0.367, SE=0.121, p=0.003) after controlling for β-amyloid load, suggesting the effect of PLXNB1 on tau tangle pathology is largely mediated by β-amyloid.

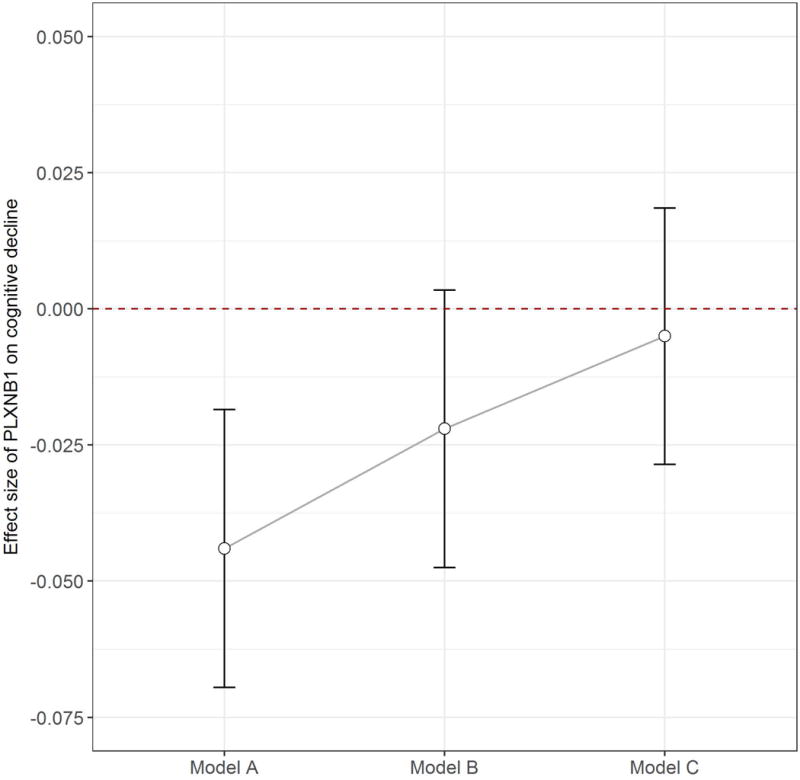

Since the bivariate examination suggests that PLXNB1 protein level was primarily correlated with AD pathology; we next tested the hypothesis that the association of PLXNB1 with cognitive decline was attenuated after accounting for AD pathology. In a linear mixed model adjusted for age, sex, education and plate, PLXNB1 abundance in the DLPFC was associated with faster cognitive decline (Estimate=-0.044, SE=0.013, p=0.001). Next, we augmented the model by further adjusting for β-amyloid load and PHFtau tangle density. Both β-amyloid (Estimate=-0.010, SE=0.004, p=0.008) and tangles (Estimate=-0.045, SE=0.003, p<0.001) were strongly related to faster decline. By contrast, the association of PLXNB1 was attenuated and no longer significant (p=0.645), suggesting that its role in aging-related cognitive decline is mediated by AD pathology (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PLXNB1 protein with cognitive decline. Figure 2 illustrates the association of PLXNB1 protein abundance with annual rate of cognitive decline before and after the adjustment for measures of AD pathology. On the x-axis, “Model A” refers to the protein association from the model without adjusting for AD pathology; “Model B” refers to the association from the model adjusted for amyloid pathology; “Model C” refers to the association from the model adjusted for both amyloid and tangle pathologies. For each model, the point estimate +/- 1.96 standard error of the effect size is shown on the y-axis.

Associations of IGFBP5, HSPB2, AK4, ITPK1 with cognitive decline and neuropathologies

We examined the other 11 targeted proteins from m109 in relation to cognitive decline. Considering that multiple proteins were tested separately, statistical significance was adjusted using Bonferroni correction at α level of 0.005 (0.05/11), although this is overly conservative since all of these genes are derived from a single network module composed of co-expressed genes. Four proteins survived full correction for multiple testing (Table 2). IGFBP5 had the strongest signal: higher IGFBP5 abundance was associated with a faster rate of cognitive decline (p=1.2×10−16). Both AK4 and HSPB2 showed similar associations with faster cognitive decline. The ITPK1 protein was also associated with decline, but the direction was reversed such that higher abundance was associated with less decline (p=7.8×10−5).

Table 2.

the association of 11 targeted proteins with cognitive decline

| Protein | Estimate, SE, p |

|---|---|

| AK4 | −0.090, 0.020, 7.3×10−6 |

| ANKRD40 | −0.0009, 0.009, 0.922 |

| BCL2L1 | −0.012, 0.022, 0.576 |

| FBXO2 | −0.023, 0.011, 0.033 |

| HSPB2 | −0.048, 0.011, 7.4×10−6 |

| IGFBP5 | −0.063, 0.008, 1.2×10−16 |

| ITPK1 | 0.056, 0.014, 7.8×10−5 |

| KIF5B | 0.006, 0.012, 0.606 |

| SASH1 | 0.006, 0.009, 0.512 |

| SLC6A12 | −0.034, 0.013, 0.006 |

| VAT1 | −0.023, 0.009, 0.017 |

SE: standard error

Results presented are estimates for interaction terms between proteins and time in years prior to death. Estimates were obtained from separate linear mixed model for longitudinal data. The models were adjusted for age, sex, education and plate.

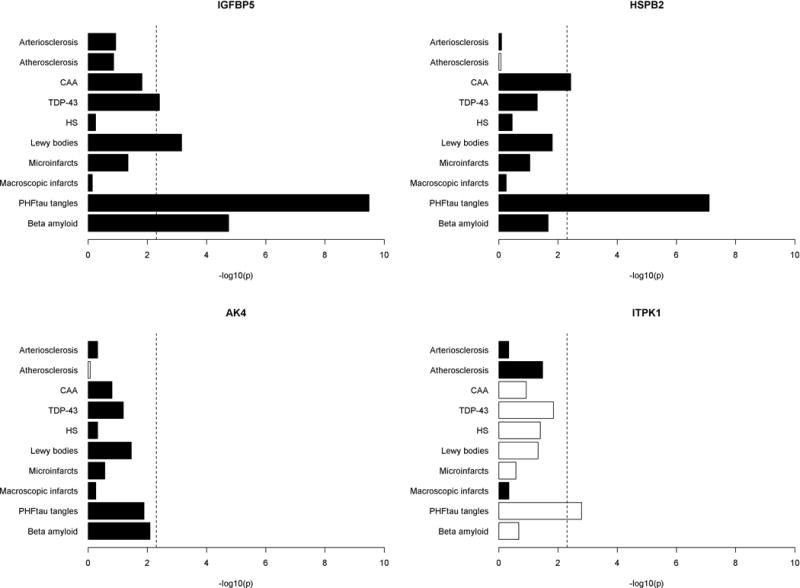

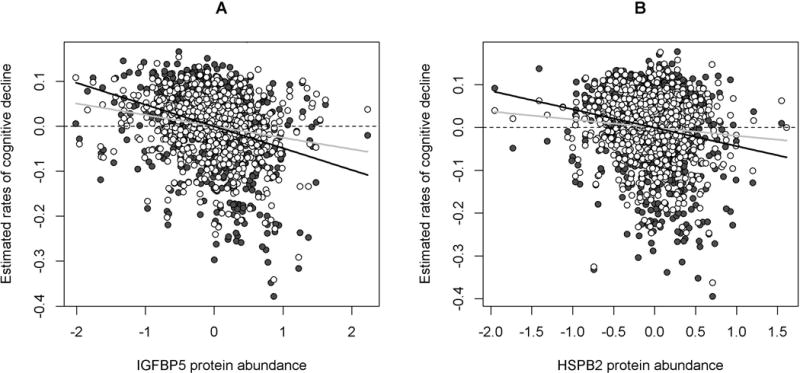

We next investigated the associations of these 4 proteins with AD and other common pathologies (Figure 3), and the results revealed distinct association patterns. IGFBP5 and HSPB2 were implicated in both AD and other neuropathologies. After correcting for multiple testing to account for the 10 different neuropathologic indices being evaluated, higher IGFBP5 protein level was associated with more β-amyloid and PHFtau tangles, as well as greater odds for Lewy bodies and more severe TDP-43 pathologies (ps<0.005). Notably, the effect of the protein on cognitive decline was not fully explained by these pathologies. Analysis using a linear mixed model showed that the association of IGFBP5 with cognitive decline was attenuated but remained significant after the adjustment for AD, Lewy body and TDP-43 pathologies (p=1.7×10−7). Figure 4a illustrates that the correlation between IGFBP5 and the rate of cognitive decline after adjusting for neuropathologies (gray line) was weaker than the one before the adjustment (black line), but it still evidently deviated from the null. This suggests that IGFBP5 may also be mediating the effects of other, as yet unmeasured neuropathologies. Similarly, higher HSPB2 protein level was associated with more PHFtau tangles and more severe CAA, and the association of HSPB2 with cognitive decline was attenuated but persisted after adjusting for tangles and CAA (p=0.020) (Figure 4b). Unfortunately, the IGFBP5 and HSPB2 genes were not included in our previous in vitro models in neurons or astrocytes, so we have no parallel in vitro data.

Figure 3.

Associations of IGFBP5, HSPB2, AK4 and ITPK1 proteins with common neuropathologies. Figure 3 illustrates associations of AK4, HSPB2, IGFBP5 and ITPK1 with common age related neuropathologies. Results are presented as -log10(p) such that higher the value, more significant the association. Each bar was derived from a separate model with corresponding pathologic index as the outcome and protein abundance the predictor. Black color represents positive association and white negative association. Vertical dotted line is the reference cut-off representing p=0.005.

Figure 4.

IGFBP5 and HSPB2 proteins with cognitive decline before and after the adjustment for neuropathologies. Figure 4 illustrates the associations of the IGFBP5 (Panel A) and HSPB2 (Panel B) proteins with cognitive decline. Dark gray circles are person-specific rates of decline estimated from a linear mixed model adjusted for demographics, plotted against protein abundance. The black line represents the regression line between protein abundance and cognitive decline without controlling for neuropathologies. White circles are person-specific rates of decline estimated from a separate linear mixed model adjusted for demographics and neuropathologies, plotted against protein abundance. The gray line represents the regression line between protein abundance and cognitive decline after controlling for neuropathologies. Notably, the gray line is flatter than the black line, but it still deviates from the horizontal reference line that represents the null.

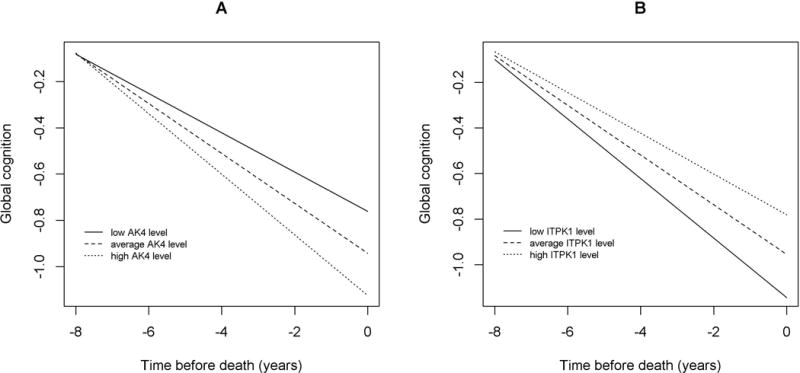

By contrast, both AK4 and ITPK1 were associated with cognitive decline (Figure 5), and the two proteins had little relationship with the brain pathologies measured in this study. None of the associations of AK4 with neuropathology measures survived the correction for multiple testing, suggesting that these pathologies were not primary drivers for the effect of AK4 on cognitive decline. We did not observe ITPK1 association with β-amyloid load. Higher ITPK1 abundance was associated with lower PHFtau tangle density, but the association of ITPK1 with cognitive decline persisted after the adjustment for the tangle pathology (p=0.002). In our previous in vitro models, knockdown of ITPK1 did not significantly alter Aβ42 secretion in neurons or astrocytes, consistent with our current findings of no relation to β-amyloid (AK4 was not tested).

Figure 5.

AK4 and ITPK1 proteins with cognitive decline. Figure 5 illustrates the associations of the AK4 (Panel A) and ITPK1 (Panel B) proteins with cognitive decline. For each panel, the line types show cognitive decline for representative females with mean age and education but different levels of protein abundance (solid lines: 10th percentile; dash lines: 50th percentile; dotted lines: 90th percentile).

Finally, we examined the extent to which the protein levels of IGFBP5, HSPB2, AK4, and ITPK1 explain the variance in person specific cognitive decline, above and beyond the effect by common neuropathologies. Consistent with our prior report, AD, cerebral infarcts, Lewy bodies, hippocampal sclerosis, TDP-43, CAA, atherosclerosis and arteriolosclerosis explained 38% variance in cognitive decline. After adjusting for these neuropathologies, IGFBP5 protein levels explained additional 3%, HSPB2 0.4%, AK4 1% and ITPK1 1%, each separately. Together, they explained a total of 4% of variance in cognitive decline, an important fraction for which we now have biological correlates to explore further.

DISCUSSION

Using a systems biology approach, we previously reported that overexpression of a RNA coexpression network module, m109, results in more β-amyloid pathology and faster cognitive decline. Our initial in vitro validation effort implicated two of these genes - INPPL1 and PLXNB1 - in β-amyloid pathology. PLXNB1 was further validated in this work, with a consistent direction of effect. All three sets of data – cortical RNA sequence data, in vitro perturbation data from human astrocytes, and now direct measure of cortical protein abundance – converge in supporting a role for PLXNB1 in AD pathology. The cross-sectional RNAseq and proteomic measures yield associations, preventing a formal comment on causality; however, the in vitro experiment suggests that one effect of PLXNB1 could be causal in astrocytes. That is, increasing levels of PLXNB1 may contribute to the accumulation of β-amyloid and is less likely to be a result of that pathology. PLXNB1 is the transmembrane receptor for Semaphorin 4D (SEMA4D). The protein functions as a GTPase activating protein for R-Ras, which downregulates R-Ras activity in response to SEMA4D and induces axonal growth cone collapse24, 25. However, little has been reported about the role of PLXNB1 in Alzheimer’s dementia. Data in this study add an important second layer of validation to our efforts to dissect cortical molecular networks to identify new targets for Alzheimer’s dementia intervention. In particular, we find that the level of protein expression is related to AD in the target human organ, providing a robust set of observations for further drug development studies. Unfortunatley, the other lead m109 candidate gene, INPPL1, was not evaluated in this effort as the SRM assay failed quality control measures. It is currently being repeated.

PLXNB1 confirms our network approach and provides a new target in relation to the biology of β-amyloid. However, it does not fully explain the role of m109 in cognitive decline. The other genes prioritized from m109 offer an exciting, complementary set of insights into the role of the module: AD and other pathologies do not fully explain either the association of higher levels of IGFBP5, HSPB2 and AK4 with faster cognitive decline, or the association of higher ITPK1 with slower decline. IGFBP5 shows the strongest signal for cognitive decline, and it is also associated with a broader range of neuropathologies. The burden of these pathologies only partially mediates the effect of this protein on cognitive decline. IGFBP5 is a binding protein that regulates the activity of insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) which play a crucial role in neurodevelopment26 and apoptosis27. Evidence from mice models show that neuronal IGFBP5 overexpression results in motor neuron degeneration and myelination defects28. HSPB2 belongs to a superfamily of heat shock proteins (HSPs) that regulate protein aggregation and clearance as well as respond to proteotoxic stress29. An earlier study on postmortem human brain reported extracellular expression of HSPB2 in plaques and CAA, suggesting the protein’s involvement in fibrillar β-amyloid deposition30. In this study, we also observed a strong relationship between HSPB2 and CAA and the protein association with β-amyloid is nominal; however, these associations do not fully explain HSPB2’s role in cognitive decline.

The last two proteins, AK4 and ITPK1, are of particular interest as both are associated with cognitive decline but have little relation to brain pathologies measured in this study. They can be considered as proteins associated with resilience. Here we define resilience as changes in cognitive function that are not explained by known neuropathologies, i.e., residual cognitive decline31. This definition assumes that all living humans have some resilience, with some having more and others less than average. Thus, resilience factors may be associated with slower or faster decline as we have shown previously32. AK4 is a mitochondrial protein that belongs to an adenylate kinase (AK) family of enzymes. Human AK4 is reported to phosphorylate AMP, dAMP, CMP and dCMP33. A prior study shows increased AK4 protein level in hypoxia-treated cells and spinal cords of ALS mice, suggesting the endogenous level of AK4 protein may elevate in response to various stress34. ITPK1 is a regulatory enzyme that plays a key role in intracellular inositol phosphate metabolism35. Higher phosphorylated forms of inositol in mammalian cells, IP6 in particular, are essential for life. Animal models show that reduced ITPK1 level can cause neural tube defects36.

The role of these four proteins in aging-related cognitive decline not explained by known neuropathologies offers an opportunity to identify molecular drivers of cognition in old age that represent novel pathways. The causes of dementia are heterogeneous, and AD, cerebral vascular disease, Lewy bodies and hippocampal sclerosis are traditionally thought to be the primary drivers for cognitive impairment and dementia37–39. However, recent evidence from clinical and postmortem data suggests that a majority of late life cognitive decline is not due to these common neuropathologies40. Indeed, other pathologic markers, TDP-43 and white matter changes for instance, also contribute to cognitive decline and dementia15, 41. Thus, proteins such as the four identified in this study may represent targets that are causally related to pathologies yet to be recognized or measured. On the other hand, it is plausible that these proteins are involved in neurobiological substrates of resilience or reserve or in response to proteotoxic stress. For instance, the HSPs families function as molecular chaperones to suppress stressed-induced protein unfolding42. As a result, change in HSPs level has been observed in aging and neurodegenerative disorders such as AD and PD43. Previous studies also show that greater amount of multiple presynaptic proteins and their interactions reduce cognitive impairment and dementia risk, independent of AD pathology and infarcts, as does neuron density as well as cortical ENC1, UNC5C and BDNF expression40, 44–47. Considering that older persons with cognitive impairment or dementia most often have mixed neuropathologies48, targets for a specific pathology are clearly of high value. However, we recently showed that there are nearly 250 combinations of neuropathologies among just over 1000 persons; no single combination was present in more than 10% of the sample and nearly 100 people had a unique combination not present in any other person49. Thus, finding a therapeutic target that can drive cognition independent of common neuropathologies may be a more practical and cost efficient approach to delaying the onset of Alzheimer’s dementia50.

Our network approach identified m109, that is, the module most proximal to cognitive decline3. Our two validation strategies have confirmed the importance of this set of genes and are beginning to dissect a series of correlated transcriptional programs involved in cognition. Our earlier work had shown that m109 is likely to be non-cell autonomous since its component genes are spread across several cell types, including astrocytes, microglia and neurons: m109 may capture a set of inter-cellular signals that are important in advancing age. PLXNB1 appears to be an important driver of a minor component of m109 which influences amyloid pathology, while IGFBP5, HSPB2, AK4, and ITPK1 provide entry points to the more exciting non-amyloid components of cognitive decline that remain to be explored. These results illustrate the strength of the network approach in prioritizing key genes for further investigation as well as the essential role of multiple, complementary validation efforts to fully explore the role of prioritized genes that are unlikely to cleanly fit in a simple narrative. It also highlights the observation that, while the reductionist perspective of a molecular network is a powerful approach to initiate projects, it does not capture the full complexity of the pathobiology of the aging brain: it is a useful platform from which to launch investigations but is just the start of a long road to understand critical phenomena that may be targeted in future therapeutic development efforts.

As proteins are the physical bases of neural networks and have served as the popular targets of most pharmaceutical interventions, our findings offer novel therapeutic targets for the prevention and treatment of cognitive decline and dementia. Nonetheless, the study has several limitations. First, lack of replicates within individual brains did not account for variability of protein expression due to spatial heterogeneity. Notably, this potential variability was effectively offset by the large sample size used in this study and the fact that variability would bias towards the null. Second, transcriptomic and proteomic data came from a single brain region, the DLPFC. As cognitive profiles may differ across brain regions, examination of other brain regions may help to identify additional proteins that are involved in cognitive impairment and dementia. Data collection from additional regions is currently underway. In addition, ROS and MAP are voluntary cohorts, and participants were older and highly educated. Thus, generalizability of these findings needs to be confirmed by samples from other longitudinal cohorts. The study also has many strengths. Findings are based on a large sample of autopsied individuals. SRM proteomics technique, in combination with annual cognitive evaluations many years prior to death and comprehensive neuropathologic assessments, provide a unique high-quality multi-level data from same individuals to perform robust statistical modeling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institute on Aging grants R01AG17917, P30AG10161, RF1AG15819, U01AG46152, R01AG042210, R01AG057911, and the Illinois Department of Public Health. Portions of this work were supported by National Institutes of Health grant P41GM103493. The proteomics work described herein was performed in the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, a national scientific user facility sponsored by the Department of Energy and located at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, which is operated by Battelle Memorial Institute for the Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC05-76RL0 1830. We are grateful to all the ROS and MAP participants, and we also thank the staff and investigators at the Rush Alzheimer’s disease Center. To obtain data from ROS and MAP for research use, please visit the RADC Research Resource Sharing Hub (www.radc.rush.edu).

Footnotes

- Conception and design of the study: LY, VAP, PLD, DAB

- Acquisition and analysis of data: LY, VAP, JAS, PDP, RLS, TLF, TS, RDS, PLD, DAB

- Drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures: LY, VAP, CG, SM, TY, RCS, ASB, JAS, PLD, DAB

POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST(/P)(P)Nothing to report

References

- 1.Zhang B, Gaiteri C, Bodea LG, et al. Integrated systems approach identifies genetic nodes and networks in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2013 Apr 25;153(3):707–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaiteri C, Ding Y, French B, Tseng GC, Sibille E. Beyond modules and hubs: the potential of gene coexpression networks for investigating molecular mechanisms of complex brain disorders. Genes, brain, and behavior. 2014 Jan;13(1):13–24. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mostafavi S, Gaiteri C, Sullivan S, et al. A molecular network of the aging brain implicates INPPL1 and PLXNB1 in Alzheimer’s disease. bioRxiv. 2017:205807. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the religious orders study. Current Alzheimer research. 2012 Jul;9(6):628–45. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Boyle PA, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the rush Memory and Aging Project. Current Alzheimer research. 2012 Jul;9(6):646–63. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Yu L, Segawa E, Sytsma J, Bennett DA. Conscientiousness, dementia related pathology, and trajectories of cognitive aging. Psychology and aging. 2015 Mar;30(1):74–82. doi: 10.1037/pag0000013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984 Jul;34(7):939–44. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Aggarwal NT, et al. Decision rules guiding the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in two community-based cohort studies compared to standard practice in a clinic-based cohort study. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;27(3):169–76. doi: 10.1159/000096129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007 Dec 11;69(24):2197–204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA. The neuropathology of probable Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Annals of neurology. 2009 Aug;66(2):200–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.21706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Tang Y, Arnold SE, Wilson RS. The effect of social networks on the relation between Alzheimer’s disease pathology and level of cognitive function in old people: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet neurology. 2006 May;5(5):406–12. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider JA, Bienias JL, Wilson RS, Berry-Kravis E, Evans DA, Bennett DA. The apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele increases the odds of chronic cerebral infarction [corrected] detected at autopsy in older persons. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2005 May;36(5):954–9. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000160747.27470.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Barnes LL, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Microinfarct pathology, dementia, and cognitive systems. Stroke. 2011 Mar;42(3):722–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Yu L, Boyle PA, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA. Cognitive impairment, decline and fluctuations in older community-dwelling subjects with Lewy bodies. Brain. 2012 Oct;135(Pt 10):3005–14. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nag S, Yu L, Capuano AW, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis and TDP-43 pathology in aging and Alzheimer disease. Annals of neurology. 2015 Jun;77(6):942–52. doi: 10.1002/ana.24388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu L, De Jager PL, Yang J, Trojanowski JQ, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. The TMEM106B locus and TDP-43 pathology in older persons without FTLD. Neurology. 2015 Mar 3;84(9):927–34. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu L, Boyle PA, Nag S, et al. APOE and cerebral amyloid angiopathy in community-dwelling older persons. Neurobiology of aging. 2015 Nov;36(11):2946–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arvanitakis Z, Capuano AW, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Relation of cerebral vessel disease to Alzheimer’s disease dementia and cognitive function in elderly people: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet Neurology. 2016 Aug;15(9):934–43. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30029-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petyuk VA, Qian WJ, Smith RD, Smith DJ. Mapping protein abundance patterns in the brain using voxelation combined with liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Methods (San Diego, Calif) 2010 Feb;50(2):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andreev VP, Petyuk VA, Brewer HM, et al. Label-free quantitative LC-MS proteomics of Alzheimer’s disease and normally aged human brains. Journal of proteome research. 2012 Jun 01;11(6):3053–67. doi: 10.1021/pr3001546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim MS, Pinto SM, Getnet D, et al. A draft map of the human proteome. Nature. 2014 May 29;509(7502):575–81. doi: 10.1038/nature13302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacLean B, Tomazela DM, Shulman N, et al. Skyline: an open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments. Bioinformatics (Oxford England) 2010 Apr 01;26(7):966–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. The National Institute on Aging and Reagan Institute Working Group on Diagnostic Criteria for the Neuropathological Assessment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiology of aging. 1997 Jul-Aug;18(4 Suppl):S1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oinuma I, Ishikawa Y, Katoh H, Negishi M. The Semaphorin 4D receptor Plexin-B1 is a GTPase activating protein for R-Ras. Science. 2004 Aug 6;305(5685):862–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1097545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ito Y, Oinuma I, Katoh H, Kaibuchi K, Negishi M. Sema4D/plexin-B1 activates GSK-3beta through R-Ras GAP activity, inducing growth cone collapse. EMBO reports. 2006 Jul;7(7):704–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Kusky J, Ye P. Neurodevelopmental effects of insulin-like growth factor signaling. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology. 2012 Aug;33(3):230–51. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marshman E, Green KA, Flint DJ, White A, Streuli CH, Westwood M. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 and apoptosis in mammary epithelial cells. Journal of cell science. 2003;116(4):675–82. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon CM, Rauskolb S, Gunnersen JM, et al. Dysregulated IGFBP5 expression causes axon degeneration and motoneuron loss in diabetic neuropathy. Acta neuropathologica. 2015 Sep;130(3):373–87. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1446-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stetler RA, Gan Y, Zhang W, et al. Heat shock proteins: cellular and molecular mechanisms in the central nervous system. Progress in neurobiology. 2010;92(2):184–211. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilhelmus MM, Otte-Holler I, Wesseling P, de Waal RM, Boelens WC, Verbeek MM. Specific association of small heat shock proteins with the pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease brains. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2006 Apr;32(2):119–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2006.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Yu L, et al. Much of late life cognitive decline is not due to common neurodegenerative pathologies. Annals of neurology. 2013;74(3):478–89. doi: 10.1002/ana.23964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu L, Boyle PA, Segawa E, et al. Residual decline in cognition after adjustment for common neuropathologic conditions. Neuropsychology. 2015;29(3):335. doi: 10.1037/neu0000159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panayiotou C, Solaroli N, Johansson M, Karlsson A. Evidence of an intact N-terminal translocation sequence of human mitochondrial adenylate kinase 4. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2010 Jan;42(1):62–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu R, Strom AL, Zhai J, et al. Enzymatically inactive adenylate kinase 4 interacts with mitochondrial ADP/ATP translocase. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2009 Jun;41(6):1371–80. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verbsky JW, Chang SC, Wilson MP, Mochizuki Y, Majerus PW. The pathway for the production of inositol hexakisphosphate in human cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005 Jan 21;280(3):1911–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411528200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Majerus PW, Wilson DB, Zhang C, Nicholas PJ, Wilson MP. Expression of inositol 1,3,4-trisphosphate 5/6-kinase (ITPK1) and its role in neural tube defects. Advances in enzyme regulation. 2010;50(1):365–72. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sonnen JA, Larson EB, Crane PK, et al. Pathological correlates of dementia in a longitudinal, population-based sample of aging. Annals of neurology. 2007 Oct;62(4):406–13. doi: 10.1002/ana.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Launer LJ, Petrovitch H, Ross GW, Markesbery W, White LR. AD brain pathology: vascular origins? Results from the HAAS autopsy study. Neurobiology of aging. 2008 Oct;29(10):1587–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nelson PT, Smith CD, Abner EL, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis of aging, a prevalent and high-morbidity brain disease. Acta neuropathologica. 2013 Aug;126(2):161–77. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1154-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Yu L, et al. Much of late life cognitive decline is not due to common neurodegenerative pathologies. Annals of neurology. 2013 Sep;74(3):478–89. doi: 10.1002/ana.23964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dawe RJ, Yu L, Leurgans SE, et al. Postmortem MRI: a novel window into the neurobiology of late life cognitive decline. Neurobiology of aging. 2016 Sep;45:169–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buchner J. Supervising the fold: functional principles of molecular chaperones. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 1996 Jan;10(1):10–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leak RK. Heat shock proteins in neurodegenerative disorders and aging. Journal of cell communication and signaling. 2014 Dec;8(4):293–310. doi: 10.1007/s12079-014-0243-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Honer WG, Barr AM, Sawada K, et al. Cognitive reserve, presynaptic proteins and dementia in the elderly. Transl Psychiatry. 2012 May 15;2:e114. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson RS, Nag S, Boyle PA, et al. Neural reserve, neuronal density in the locus ceruleus, and cognitive decline. Neurology. 2013 Mar 26;80(13):1202–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182897103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buchman AS, Yu L, Boyle PA, Schneider JA, De Jager PL, Bennett DA. Higher brain BDNF gene expression is associated with slower cognitive decline in older adults. Neurology. 2016 Feb 23;86(8):735–41. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.White CC, Yang HS, Yu L, et al. Identification of genes associated with dissociation of cognitive performance and neuropathological burden: Multistep analysis of genetic, epigenetic, and transcriptional data. PLoS Med. 2017 Apr;14(4):e1002287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007 Dec 11;69(24):2197–204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boyle PA, Yu L, Wilson RS, Leurgans SE, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Person-specific contribution of neuropathologies to cognitive loss in old age. Ann Neurol. 2017 Dec 15; doi: 10.1002/ana.25123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bennett DA. Mixed pathologies and neural reserve: Implications of complexity for Alzheimer disease drug discovery. PLoS medicine. 2017 Mar;14(3):e1002256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.