Abstract

The growing prominence of community-based participatory research (CBPR) presents as an opportunity to improve tobacco-related intervention efforts. CBPR collaborations for tobacco/health, however, typically engage only adults, thus affording only a partial understanding of community context as related to tobacco. This is problematic given evidence around age of tobacco use initiation and the influence of local tobacco environments on youth. The CEASE and Resist youth photovoice project was developed as part of the Communities Engaged and Advocating for a Smoke-free Environment (CEASE) CBPR collaboration in Southwest Baltimore. With the broader CEASE initiative focused on adult smoking cessation, CEASE and Resist had three aims: (1) elucidate how youth from a high-tobacco-burden community perceive/interact with their local tobacco environment, (2) train youth as active change agents for tobacco-related community health, and (3) improve intergenerational understandings of tobacco use/impacts within the community. Fourteen youth were recruited from three schools and trained in participatory research and photography ethics/guiding principles. Youth met at regular intervals to discuss and narrate their photos. This article provides an overview of what their work revealed/achieved and discusses how including participatory youth research within traditionally adult-focused work can facilitate intergenerational CBPR for sustainable local action on tobacco and community health.

Keywords: community-based participatory research, health research, tobacco prevention and control, child/adolescent health, health promotion

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use continues to account for a disproportionate amount of morbidity and mortality across the United States (Thun et al., 2013), with low-income, urban, and communities of color especially burdened by tobacco-related causes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015b). Research shows that lower income communities and communities of color tend to have higher tobacco retail densities and advertising (J. G. L. Lee, Henriksen, Rose, Moreland-Russell, & Ribisl, 2015; Rodriguez, Carlos, Adachi-Mejia, Berke, & Sargent, 2013), and there is a growing body of place-based research that demonstrates linkages between local tobacco environments and tobacco-related behaviors and health outcomes. For example, the local tobacco retail and advertising environment has been identified as a critical element of place context that influences tobacco use and cessation (Cantrell et al., 2015; Peterson, Lowe, & Reid, 2005; Reitzel et al., 2011). Even so, efforts to curb tobacco use and mitigate consequent outcomes have largely come up short, especially for low-income communities of color (Patten et al., 2008). Most successful interventions to date have been the result of work with largely middle to higher income and predominantly White communities, with very little success demonstrated in communities suffering from the largest tobacco-related inequities (Fagan et al., 2007).

The growing prominence of community-based participatory research (CBPR) approaches has presented as an opportunity to improve intervention efforts and has gained increasing traction within tobacco-related research (Andrews, Newman, Heath, Williams, & Tingen, 2012; Messiah et al., 2015; Sheikhattari et al., 2016). Many CBPR collaborations concerning tobacco, however, typically engage only adult members of affected communities (Andrews et al., 2012), and thus afford only a partial understanding of community context as related to tobacco use. This, of course, is problematic given the evidence indicating that tobacco use initiation commonly begins during youth (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015a). Moreover, literature has demonstrated negative tobacco-related behaviors and outcomes among youth who have more tobacco stores and advertising in their communities and near their schools (Adams, Jason, Pokorny, & Hunt, 2013; Henriksen, Schleicher, Feighery, & Fortmann, 2010; Lipperman-Kreda et al., 2014; Mennis & Mason, 2016; Mennis, Mason, Way, & Zaharakis, 2016). Efforts to reduce tobacco-related health inequities, especially those at the community level taking a place-based approach, accordingly could stand to benefit greatly from exploring opportunities to more critically involve youth in the CBPR process. Ideally, such involvement would include avenues for active youth participation in research design and implementation, and any policy and action strategizing work for research translation. Furthermore, given increasing awareness of the importance of taking a life-course approach to health promotion and intervention (Ferraro, Schafer, & Wilkinson, 2016; Lynch & Smith, 2005), intergenerational efforts involving both adults and youth could prove quite valuable in addressing tobacco-related health inequities.

In this article we provide an overview of a CBPR collaborative developed in Southwest Baltimore to improve tobacco-related community health, Communities Engaged and Advocating for a Smoke-free Environment. Specifically, we present the process and findings from a youth photovoice project—CEASE and Resist— designed to facilitate inclusion of critical perspectives and contributions of youth within the overall CBPR collaborative. We developed the project with the belief that the most effective strategies for long-term success and sustainability are those which engage adults and youth and promote critical discussion and action across generations—allowing for cross-generational perspective sharing and the elucidation of potential intergenerational differences in tobacco-related experiences, perceptions, concerns, and risks. As such, we describe how integrating youth photovoice into an ongoing adult-led and adult-focused CBPR smoking cessation project can create opportunities for sustainable inter-generational action for tobacco control. The article begins with an overview of the CEASE collaborative and is followed by the presentation of the CEASE and Resist photovoice process, methods, and a findings snapshot. The article closes with a discussion of local CEASE and Resist impacts and prospects for intergenerational CBPR, as well as plans and prospects for future iterations of CEASE and Resist.

BACKGROUND

What Is CEASE?

Communities Engaged and Advocating for a Smoke-free Environment, or CEASE, is a CBPR project that brings together an interdisciplinary community action board (CAB) of residents and coresearchers with health, education, sociology, psychology, faith-based, and art backgrounds (Wagner et al., 2016). CEASE is designed to improve tobacco prevention and cessation outcomes among inner-city residents in communities with high rates of poverty and adult tobacco use in Southwest Baltimore City. Southwest Baltimore has one of the highest densities of tobacco retailers in the Baltimore City: 45 stores/10,000 people, compared to 24 stores/10,000 people for Baltimore City overall (Petteway & Ames, 2011). Moreover, local research has shown that up to 54% of Southwest Baltimore residents smoke (Sheikhattari et al., 2010), compared with 25% of all Baltimore City residents overall (Petteway & Ames, 2011). These same Southwest Baltimore communities also have the highest death rates from lung cancer and heart disease in the city (Petteway & Ames, 2011), for each of which tobacco use has impacts and implications.

After several years of work to build a trustable relationship and a shared agenda, the CEASE initiative has been able to provide cessation services to more than 800 community residents with nicotine dependence (Wagner et al., 2016). Part of this project, examining the effectiveness of group-based versus individual counseling services, has been tested through experimental methodologies with overall quit rates comparable to other trials (Sheikhattari et al., 2016; Wagner et al., 2016). In addition, a variety of other preventive research/intervention strategies have been developed, including the CEASE and Resist youth photovoice project.

What Is CEASE and Resist?

CEASE and Resist is a youth participatory research project developed to create opportunities for youth to critically engage in the CBPR process as resident-experts alongside the adults, with the purpose of ensuring that youth experiences and perspectives were included in the development of community policy and action strategies based on the CEASE initiative. The overall goal was to gain an understanding of how youth from Southwest Baltimore perceive tobacco-related issues and interact with their local tobacco environment, as well as train them to become active change agents for community health. The research team for this project and the work reported here included two faculty at local schools of public health, an epidemiologist at a local health department, a youth programs director at a local community organization and charter school, and various other community organization leaders who served on the CEASE CAB.

CEASE and Resist youth used a participatory research method commonly referred to as photovoice (Catalani & Minkler, 2010; Wang, 2006; Wang & Burris, 1997). Photovoice uses photography, narration, and critical discussion to identify community strengths and weaknesses and facilitate participants’ empowerment for action (Wang, 2006). It has been used as a research and community assessment tool for years and has been used to critically engage youth in health-related research on a broad range of topics (Catalani & Minkler, 2010; Wang, 2006). This has included youth photovoice examining pro- and antitobacco community environment characteristics (Tanjasiri, Lew, Kuratani, Wong, & Fu, 2011), documenting aspects of the tobacco retail environment (J. P. Lee, Lipperman-Kreda, Saephan, & Kirkpatrick, 2013), and exploring perceptions regarding tobacco use in relation to cancer (Woodgate & Busolo, 2015). With roots in critical education, feminist theory, and other participatory frameworks and photo-elicitation traditions (Wang & Burris, 1997), photovoice projects are noted for their ability to transform perspectives on pressing community concerns and inspire action for change. More important, they afford traditionally excluded community members an avenue for social action and civic engagement. In this way, photovoice serves to enhance community member agency within contexts that tend to impede or masked it, facilitating empowerment and building action capacity. We accordingly identified photovoice as an ideal method and process to critically engage community youth and amplify their collective voice within deliberations and strategizing around an important community issue such as tobacco control and the tobacco environment.

The photovoice method is premised on three core goals of the research process (Wang & Burris, 1997): (1) enable people to record and reflect on their community’s strengths and concerns, (2) promote critical dialogue and knowledge about important issues through large and small group discussions of photographs, and (3) reach policy makers. This methodology, accordingly, is perfectly suited for the CEASE collaborative’s CBPR orientation, drawing strength from its ability to elicit critical insight, perspective, and contextualized meanings narrated in the voice/words of youth participants. The photovoice process generally entails nine steps (not necessarily always followed in sequence) as outlined in Table 1 (adapted from Wang, 2006).

Table 1.

General Photovoice Process

| 1. Identification and selection of key stakeholders (policy makers, community leaders) |

| 2. Recruitment of photovoice participants |

| 3. Introduction of the photovoice methodology to participants and facilitation of a discussion about photo-taking safety, cameras, power, and ethicsa |

| 4. Collection of informed consent and/or assent |

| 5. Posing of initial themes for taking photosb |

| 6. Distribution of cameras and review of how to use them |

| 7. Provision of time for participants to take photos if done as a guided/accompanied activity. Otherwise, provision of guidelines for when to take photos (e.g., daylight, during routine daily activities) |

| 8. Meeting to discuss photos and identify themes |

| 9. Planning with participants to share photos, narratives, and recommendations with policy makers and community leaders |

NOTE: CEASE = Communities Engaged and Advocating for a Smoke-free Environment.

Youth in the CEASE and Resist project were also provided basic training in elements of photography, for example, composition (contrast, color, leading lines, natural frames etc.) and lighting (indoor/outdoor, natural, flash, concerns etc.).

Youth were also provided basic background and training on community health, tobacco health in the community, and concepts related to social determinants of health and health equity.

METHOD AND PROCESS

Recruitment and Training

For the CEASE and Resist photovoice project, 14 youth between fifth and eighth grade were recruited from three schools in Southwest Baltimore. CEASE Community Action Board (CAB) members visited with local school principals to discuss the project and identify opportunities for collaboration and support in the recruitment process, as well as for project activities (e.g., meeting space that afforded computers for photo review and editing). Information packets for the principals and for sending home with potential youth participants were prepared by the CAB in advance of these discussions, detailing the CEASE initiative and the planned photovoice project. This process was greatly facilitated by strong ties CAB members had within the community and their existing knowledge of key community leaders and assets that could be made available to the CEASE and Resist project. Indeed, the project would not have been possible, whether due to logistics or recruitment limitations, without core CAB members embracing it, committing time and resources to recruitment, and ensuring adequate meeting space was secured within the community.

Once recruitment was completed, CEASE and Resist facilitators held two project Overview and Orientation Sessions with youth and their parent/guardians to go over project process, logistics, and discuss matters related to project risks, benefits, confidentiality, and consent/assent. There were two primary facilitators for the project. One facilitator (one of the authors) had developed and led two youth photovoice projects previously, and at the time was serving as an epidemiologist at a local health department. The other facilitator was the youth programs director at a local community organization and neighborhood charter school attended by some of the youth participants. The CEASE facilitators provided parents/guardians and youth basic training/background in community health, tobacco-related health in the community, and concepts related to social determinants of health and health equity. No informed consent (from parent/guardian) or assent forms (from youth) were obtained until after potential youth participants and their parents/guardians attended these meetings. The Human Subjects Protection Plan was approved by the CEASE Advisory Board and then by Morgan State University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB Nos. 08/04-0023 and 11/02-0011).

Photovoice Process

Once consent/assent was obtained, youth attended two Participant Training Sessions covering basic participatory research principles, camera use, and ethics/guiding principles of photography, including concerns around participant safety and taking photos of people. CEASE facilitators then provided youth with digital cameras and instructed them to begin taking photos on the project theme: youth perspectives on the tobacco environment and community health. Photo-taking was not planned as a guided, group, or a CEASE facilitator-led process; rather, youth were free to take photos on their own time as they went about their daily lives.

CEASE facilitators held a total of eight Photo Review Sessions at regular intervals (i.e., weekly) where youth brought their photos for discussion. At each Review Session, youth copied their photos to computers, selected their favorite five photos of the current photo “batch,” and completed a photovoice narrative for each of their favorites with guidance from CEASE facilitators. Each week, facilitators asked participants to generate narratives on why they took each particular photo. The process was guided by the SHOWED technique, introduced in the public health literature by Wallerstein and Bernstein (1988) and later adapted (Wang, 1999). SHOWED (or sometimes SHOWeD) represents six critical inductive questions for guiding comprehensive dialogues and generating narratives. SHOWED questions have varied slightly in application—usually with minor adaptations to the “E”—but generally include the following: (1) What do you See in this photograph? (2) What is really Happening in the photograph? (3) How does this relate to Our lives? (4) Why do these issues exist? (5) How can we become Empowered by our new social understanding? and (6) What can we Do to address these issues? (Wallerstein & Bernstein, 1988). Participants in this project used SHOWED as part of a guide that included an additional set of five inductive questions/prompts, forming the acronym PHOTO (see Pies & Parthasarathy, 2008): (1) Describe your Picture, (2) What is Happening in your picture? (3) Why did you take a picture Of this? (4) What does this picture Tell us about life in your community? and (5) How does this picture provide Opportunities to improve life in your community? We included PHOTO along with SHOWED because we believed that its more simplistic phrasing was easier to process by participants and because we believed there were overlapping yet distinct concepts in each that bring value in formulating narratives and discussion (e.g., Empowerment and Opportunities).

At the next-to-final Review Session, participants selected their final favorite five photos to be printed and framed. Youth participants received a stipend for each training and Photo Review Session.

Photovoice Thematic Analysis

Youth participants took hundreds of photos during the project. Of these photos, 62 were identified by the youth as their favorite and most meaningful/important photos. Youth deemed these photos worthy of sharing with the broader community, and each was accordingly printed and framed for exhibition. Out of this pool of 62 framed photos, youth selected their top 25 favorite photos through consensus—resulting in a final count of 25 framed photos for thematic analysis. For the thematic analysis, first the youth sorted the 25 photographs according to broad themes as they saw related tobacco and community health. As a CBPR project, consensus building is the cornerstone for any decision making, so the youth then presented the themes to the photovoice facilitators, other researchers, staff, and CAB members. Grouping decisions were based not only on the photo content but also the photo intent as communicated by the youth through their narratives. All thematic grouping modifications and names were finalized through consensus with the youth participants.

CEASE AND RESIST FINDINGS SNAPSHOT AND IMPACT

Through the collaborative theming process, the 25 selected photos revealed four prominent themes: Harmful Nicotine, Tobacco and Community Health, Marketing, and Prevention and Help. These thematic group names were decided on collaboratively by youth participants, photovoice facilitators, and research team members.

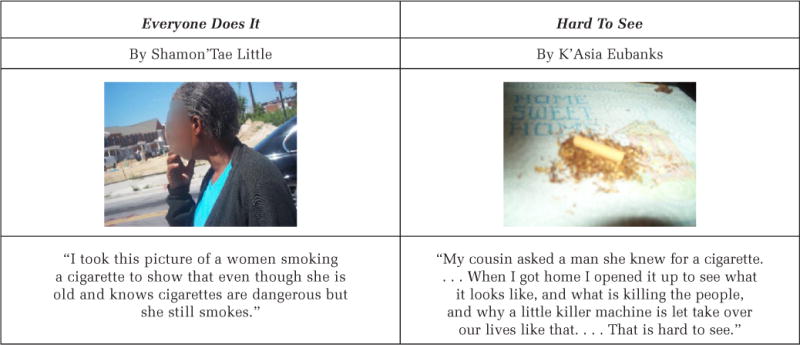

Harmful Nicotine

Eight of the final 25 photographs chosen by participants related to the harms of nicotine. Photos illustrated different facets of nicotine as an addictive drug, ranging from “hidden” chemicals to the compulsive use of tobacco. Examples of photographs and narratives are shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Harmful Nicotine

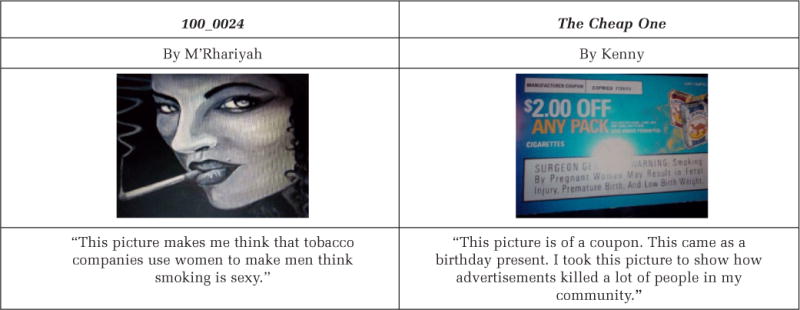

Marketing

This was a topic that greatly concerned participants, and they grouped six photos within this theme. Their keen eye actually uncovered many of the tricks the industry uses to get new customers (Figure 2), including associating smoking with sex and sexiness, and plastering local corner stores with brightly colored posters advertising discounts and sales.

FIGURE 2.

Marketing

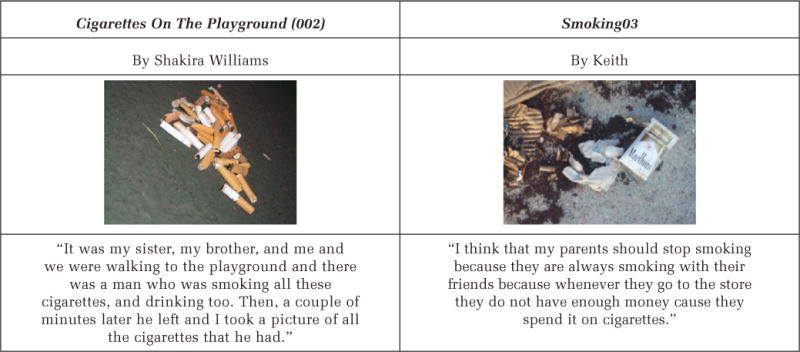

Tobacco and Community Health

Youth selected five photos within this thematic group. Even at their young age, the youth who participated in the CEASE and Resist project realized several of the deleterious consequences of tobacco to their community health. Notably, they identified important indirect health consequences of smoking at the community level, for example, neighborhood pollution from tobacco packaging and cigarette butts, and at the family/household level, for example, potential food insecurity due to spending limited financial resources on cigarettes. Again, exemplary photographs and narratives are included in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Tobacco and Community Health

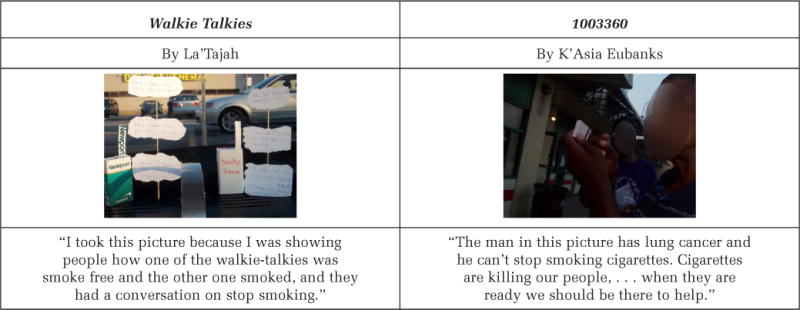

Prevention and Help

Youth grouped and analyzed a total of six photos within this theme. Many participants found creative ways to communicate their thoughts on tobacco use and the importance of cessation services (Figure 4). While youth were not explicitly guided in doing so, project facilitators encouraged them to think broadly and creatively in how they chose to capture tobacco-related issues in their community. And one of the facilitators had an interest and secondary project focus on street theatre as an intervention approach, which may have inspired CEASE and Resist participants’ photographic work.

FIGURE 4.

Prevention and Help

CEASE and Resist Community Impact

A core goal of photovoice is to share participants’ work with community leaders and policy makers. For this project, the research team worked with youth over several sessions to discuss and edit the narratives for their top 25 framed photos to prepare them for public exhibition. An initial exhibition was collaboratively planned at a community venue as a celebration ceremony for the youth. Participants’ relatives and friends were invited, along with community partners and local government representatives. After a brief description of the project, each participant discussed what she or he had learned through the process. The chosen photographs were displayed and, for that particular occasion, the youth were available for comment and discussion.

Following the reception, members of the CEASE research team were approached with an invitation for the youth to exhibit their photographs at City Hall. This gave youth and their families an opportunity to discuss their tobacco-related concerns with their city council representatives and city health officials. The exhibition was mounted at the central entry corridor so all councilmembers, staff, and visitors could view the photographs. Their work revealed perspectives on the tobacco environment that had not been included in community or city-wide efforts to address tobacco-related health concerns, particularly their views on how tobacco use affects their neighborhood environmental quality and household food security. Moreover, their work revealed how they, as youth, perceive and process their daily exposures to the local tobacco retail and marketing environment. At the time of the project, there had not been any youth-focused or youth-led tobacco efforts in their specific community, and city-wide efforts through the local health department (where one of the authors led community epidemiology work) were focused almost exclusively on the provision of adult cessation services. Thus, the work completed by the youth in this project broke ground in numerous ways, not the least of which was their presentation of their work at City Hall—a youth tobacco photovoice first for their community.

Following the City Hall exhibit, little further discussion of the photographs and their narratives took place with these initial youth participants in part due to CEASE staff turnover, in part due to competing scholarly activities, and in part due to the some of the youth moving away to attend schools outside the Southwest Baltimore community where CEASE is anchored. However, this initial work laid the foundation for numerous future activities in which youth have been playing a central role within the overall CEASE collaborative. For example, youth participants’ made presentations at two annual CEASE conferences in 2014 and 2015 and helped develop and complete two subsequent photovoice projects in 2014 and 2015. For each of these projects, two CEASE and Resist youth took responsibility to lead photovoice facilitation activities. These projects led directly to the formation of the Youth Tobacco Advisory Council (YTAC) in 2014, with members selected from different middle and high schools within the community. Two CEASE and Resist participants led recruitment for the YTAC and helped develop the YTAC agenda and areas for policy recommendations. The council—initially guided by CEASE and Resist youths’ research—remains active, having monthly meetings to discuss policy options and present recommendations to the Baltimore City Tobacco Coalition, and provide testimony to support tobacco control policies and regulations—such as the passage of the Clean Air Act for the State of Maryland and the City of Baltimore. The City Health Department, after becoming engaged through the initial photovoice project presented here, has funded several projects under CEASE and YTAC youth leadership.

DISCUSSION AND FUTURE DIRECTION

Toward Sustainable Intergenerational Change

Photovoice can provide a unique opportunity for adult community members, public health researchers and practitioners, and local policy makers to see and learn from the perspectives of youth living in communities disproportionately burdened by tobacco-related problems. The CEASE and Resist photovoice project successfully engaged and trained youth in tobacco-related community-based research, and in doing so transformed CEASE from being an exclusively adult-led and adult-focused CBPR project, to being one that is youth-inclusive and intergenerational in nature. In this context, youth participants’ work revealed important and missing perspectives on the local tobacco environment and opened up the door for broader youth participation and city–community collaboration. Indeed, the youth photovoice project was instrumental in establishing a more dynamic and open communication between city agencies, council members, community residents, and members of the CEASE collaborative. Even so, this project also highlights the challenges of CBPR—namely, the challenge of sustainability and longer term impact. As noted above, there was very little project-related activity with many of the initial CEASE youth following the City Hall exhibit, and CEASE and Resist lost momentum. Maintaining the CEASE and Resist project for multiple cohorts of youth, deepening discussions with local policy makers, and pursuing community-specific policy change were desired goals that, of course, require more than a few photo exhibits. Thus, even though the CEASE collaborative, youth participants and their families, and CEASE partners showed commitment throughout the CEASE and Resist process, and even though many remain committed, the overall impact potential of CEASE and Resist was not fully realized in the initial project.

However, while there were limitations to the direct impacts of the initial CEASE and Resist project (apart from making CEASE an intergenerational endeavor), it had multiple indirect impacts that remain significant not only for youth but also adults. For example, although not originally included as a project aim, some parents became quite engaged in the process. They began acting as chaperons for their children (accompanying their youth to meetings and community venues to take pictures for safety, and so forth) and became increasingly engaged over the duration of the project. Many started to sign up for the smoking cessation classes offered by CEASE, some became CEASE volunteers, and others became CBPR partners as CAB members. This is consistent with other research studies showing that often participants of photovoice assume leadership roles in addition to research and service objectives (Carlson, Engebretson, & Chamberlain, 2006; Minkler, Garcia, Williams, LoPresti, & Lilly, 2010).

Furthermore, parent engagement has resulted in the formal development of a youth initiative that has benefited their local community and other areas of the city. For example, two additional youth photovoice projects were implemented in years 2014 and 2015, drawing leadership and guidance from parents and youth of the initial CEASE and Resist project. Furthermore, other CEASE youth-based programs such as the YTAC have been continuously funded in the past 3 years by the city health department. Additionally, 6 out of the 14 youth originally recruited for the CEASE and Resist project have become antitobacco advocates and led CEASE youth-based projects in roles such as facilitating meetings, coaching dance and theatrical performances, and presenting at the Baltimore City Tobacco Advisory Council. The CEASE and Resist project also created capacity and set the stage for other school-based tobacco prevention initiatives. In 2014, the CEASE partnership evaluated the impact of photovoice on leadership development among middle school students (Henry, 2015). And photovoice has been used further as a strategy to engage students in educating their community about harmful effects of tobacco—work that has led to the development of other tobacco-related afterschool performing arts interventions (Addison, 2015).

Thus, while the initial CEASE and Resist project lost steam, it opened the door for youth inclusion and planted the seeds for longer term and more dynamic work involving youth within the overall CEASE CBPR partnership. CEASE and Resist has accordingly served to spark a truly intergenerational CBPR project within which both youth and adults—and both children and their parents—now have the opportunity to actively contribute to and benefit from. This has not only strengthened and enhanced the overall CEASE collaborative in terms of programmatic direction and reach but has greatly improved the collaborative’s prospects for sustainability. Not only has CEASE been able to connect with and impact adult smokers and nonsmokers, but importantly, it has now simultaneously been able to involve and influence youth—facilitating their empowerment and perhaps preventing their and their peer’s future tobacco use. Such an intergenerational approach means that efforts within the Southwest Baltimore community aimed at addressing tobacco and community health will continue to reflect perceptions and experiences of residents across the age spectrum. This could accordingly improve prospects for developing and implementing meaningful place-based and age/life stage-specific interventions, policies, and action strategies going forward. This intergenerational approach is accordingly responsive to research articulating the importance of lifecourse perspectives within public health, particularly with regard to tobacco use (Ferraro et al., 2016; Niemelä et al., 2017; Taylor et al., 2014).

CEASE and Resist youths’ level of engagement during and after the project is consistent with other youth-led work on tobacco that suggests participatory approaches can effectively build youth awareness and build efficacy (Hinnant, Nimsch, & Stone-Wiggins, 2004; Winkleby et al., 2004). However, while we did expect the project to help transform CEASE into an intergenerational CBPR partnership, we did not anticipate or expect participants to remain so actively involved as leaders and conveners in subsequent projects. We believe this speaks to the ability of photovoice as an “empowerment” process to promote leadership development. Photovoice commonly involves participants who have not yet engaged socially or politically on important community issues, but they experience, encounter, and contend with these issues through their daily lives. They accordingly possess a wealth of embodied and lived expertise of their local contexts. However, in the absence of formal structures and explicit opportunities for civic and political participation, participants are not routinely afforded avenues or venues to voice concerns and take collective action. In this capacity, photovoice, especially for youth, can serve as the initial spark to their formal engagement, serving not necessarily to create leadership, but rather to reveal it—that is, to unmask and amplify the already existing leadership qualities present within communities. We believe the visual and very tangible nature of photovoice in this context renders the connections between research and action more apparent to youth and that this helps youth recognize their power and ability to meaningfully contribute to their communities. Thus, we see the conscientization (Freire, 2000) element of photovoice as fundamental to their initial realization and visualization of themselves as leaders, and as their entrée to continued leadership development.

While the benefits of CBPR are well-documented, less is known about the potential value and impacts of intergenerational CBPR work. Similarly, intergenerational photovoice projects on health-related topics remain quite rare (Garcia et al., 2013). However, the limited work completed to date suggests it is an area worth growing. And while the goal of the work we present here was focused only on how to make the overall CEASE CBPR partnership intergenerational—that is, integrate youth perspective via photovoice—the extent to which youth photovoice participants’ parents became engaged during and after CEASE and Resist suggests a valuable opportunity to actually develop true intergenerational photovoice projects involving both parents and children. At present, plans are underway for the development of a second iteration of CEASE and Resist, which will take an intentional inter-generational design to further explore tobacco-related experiences, perceptions, risks, and opportunities within and between multiple generations of Southwest Baltimoreans. Coupling photovoice with participatory mapping methodologies, mediated through smartphone use and web-based GIS (geographic information system), is a strong consideration.

Conclusion

Tobacco use remains a fundamental area of concern for improving community well-being, and tobacco-related health inequalities warrant sustained attention. As collective public health efforts continue to take on these challenges, it will be increasingly important to identify and pursue opportunities for more inclusive and dynamic research and practice approaches. The CEASE and Resist photovoice project presented here illustrates one such approach, bringing youth perspective into the fold of an ongoing CBPR project focused on adult smoking cessation. As such, this work makes a unique contribution to the tobacco use literature, highlighting the potential value and promise of inter-generational CBPR work on tobacco and community health, and the potentially instrumental role youth photovoice can play in facilitating this initial shift. Similarly focused interventions and programs, especially those with a place-based and community- specific focus, might benefit from not only actively including youth but also from integrating participatory methodologies. Taken together, such an integrated approach may improve sustainability, which in turn can enhance prospects for local policy and practice change. Future efforts should consider deliberate inter-generational CBPR designs from the outset and explore the utility of participatory methods like photovoice for deepening collaborative efforts, aligning adult–youth/parent–child community health interests, and strengthening intergenerational bonds within the community.

Acknowledgments

The authors completed this research on behalf of the CEASE Initiative (Communities Engaged and Advocating for a Smoke-free Environment). We acknowledge members of the CEASE partnership including the members of the community action board, peer motivators, the staff and administrators of People’s Community Health Center, and other community partners and organizations that supported our planning and hosted CEASE programs. This research received financial support from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (Grants MD000217 and MD002803), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grants DA012390 and DA019805), and Pfizer Inc. The Human Subjects Protection Plan was approved by the CEASE Advisory Board, and then by Morgan State University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 11/02-0010).

References

- Adams ML, Jason LA, Pokorny S, Hunt Y. Exploration of the link between tobacco retailers in school neighborhoods and student smoking. Journal of School Health. 2013;83:112–118. doi: 10.1111/josh.12006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addison T. Paper presented at 143rd meeting of the American Public Health Association: Health in All Policies. Chicago, IL: 2015. Nov, Developing youth leadership and empowerment through CBPR. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JO, Newman SD, Heath J, Williams LB, Tingen MS. Community-based participatory research and smoking cessation interventions: A review of the evidence. Nursing Clinics of North America. 2012;47:81–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell J, Anesetti-Rothermel A, Pearson JL, Xiao H, Vallone D, Kirchner TR. The impact of the tobacco retail outlet environment on adult cessation and differences by neighborhood poverty. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2015;110:152–161. doi: 10.1111/add.12718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson ED, Engebretson J, Chamberlain RM. Photovoice as a social process of critical consciousness. Qualitative Health Research. 2006;16:836–852. doi: 10.1177/1049732306287525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalani C, Minkler M. Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Education & Behavior. 2010;37:424–451. doi: 10.1177/1090198109342084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco use among middle and high school students – United States, 2011-2014. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports. 2015a Apr 17; Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6414a3.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current cigarette smoking among adults – United States, 2005-2014. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports. 2015b Nov 13; doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6444a2. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6444a2.htm?s_cid=mm6444a2_w. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ferraro KF, Schafer MH, Wilkinson LR. Childhood disadvantage and health problems in middle and later life: Early imprints on physical health? American Sociological Review. 2016;81:107–133. doi: 10.1177/0003122415619617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum; 2000. (30th anniversary ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Garcia CM, Aguilera-Guzman RM, Lindgren S, Gutierrez R, Raniolo B, Genis T, Clausen L. Intergenerational photovoice projects: Optimizing this mechanism for influencing health promotion policies and strengthening relationships. Health Promotion Practice. 2013;14:695–705. doi: 10.1177/1524839912463575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Feighery EC, Fortmann SP. A longitudinal study of exposure to retail cigarette advertising and smoking initiation. Pediatrics. 2010;126:232–238. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry S. Paper presented at 143rd meeting of the American Public Health Association: Health in All Policies. Chicago, IL: 2015. Nov, Evaluation of a photovoice project among youth to address tobacco in a Baltimore city community. [Google Scholar]

- Hinnant LW, Nimsch C, Stone-Wiggins B. Examination of the relationship between community support and tobacco control activities as a part of youth empowerment programs. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31:629–640. doi: 10.1177/1090198104268680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JGL, Henriksen L, Rose SW, Moreland-Russell S, Ribisl KM. A systematic review of neighborhood disparities in point-of-sale tobacco marketing. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105:e8–e18. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JP, Lipperman-Kreda S, Saephan S, Kirkpatrick S. Tobacco environment for Southeast Asian American youth: Results from a participatory research project. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2013;12:30–50. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2013.759499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipperman-Kreda S, Mair C, Grube JW, Friend KB, Jackson P, Watson D. Density and proximity of tobacco outlets to homes and schools: relations with youth cigarette smoking. Prevention Science. 2014;15:738–744. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0442-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch J, Smith GD. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:1–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennis J, Mason M. Tobacco outlet density and attitudes towards smoking among urban adolescent smokers. Substance Abuse. 2016;37:521–525. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2016.1181135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennis J, Mason M, Way T, Zaharakis N. The role of tobacco outlet density in a smoking cessation intervention for urban youth. Health & Place. 2016;38:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.health-place.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messiah A, Dietz NA, Byrne MM, Hooper MW, Fernandez CA, Baker EA, Lee DJ. Combining community-based participatory research (CBPR) with a random-sample survey to assess smoking prevalence in an under-served community. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2015;107:97–101. doi: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Garcia AP, Williams J, LoPresti T, Lilly J. Sí Se Puede: Using participatory research to promote environmental justice in a Latino community in San Diego, California. Journal of Urban Health. 2010;87:796–812. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9490-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemelä S, Räisänen A, Koskela J, Taanila A, Miettunen J, Ramsay H, Veijola J. The effect of prenatal smoking exposure on daily smoking among teenage offspring. Addiction. 2017;112:134–143. doi: 10.1111/add.13533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten CA, Brockman TA, Ames SC, Ebbert JO, Stevens SR, Thomas JL, Carlson JM. Differences among Black and White young adults on prior attempts and motivation to help a smoker quit. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson NA, Lowe JB, Reid RJ. Tobacco outlet density, cigarette smoking prevalence, and demographics at the county level of analysis. Substance Use & Misuse. 2005;40:1627–1635. doi: 10.1080/10826080500222685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petteway R, Ames A. 2011 Baltimore City neighbor-hood health profiles. Baltimore, MD: Baltimore City Health Department, Office of Epidemiology and Planning; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Reitzel LR, Cromley EK, Li Y, Cao Y, Dela Mater R, Mazas CA, Wetter DW. The effect of tobacco outlet density and proximity on smoking cessation. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101:315–320. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.191676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez D, Carlos HA, Adachi-Mejia AM, Berke EM, Sargent JD. Predictors of tobacco outlet density nationwide: a geographic analysis. Tobacco Control. 2013;22:349–355. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikhattari P, Apata J, Kamangar F, Schutzman C, O’Keefe A, Buccheri J, Wagner FA. Examining smoking cessation in a community-based versus clinic-based intervention using community-based participatory research. Journal of Community Health. 2016;41:1146–1152. doi: 10.1007/s10900-016-0264-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanjasiri SP, Lew R, Kuratani DG, Wong M, Fu L. Using photovoice to assess and promote environmental approaches to tobacco control in AAPI communities. Health Promotion Practice. 2011;12:654–665. doi: 10.1177/1524839910369987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AE, Howe LD, Heron JE, Ware JJ, Hickman M, Munafò MR. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring smoking initiation: Assessing the role of intrauterine exposure: Smoking in pregnancy and offspring smoking. Addiction. 2014;109:1013–1021. doi: 10.1111/add.12514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thun MJ, Carter BD, Feskanich D, Freedman ND, Prentice R, Lopez AD, Gapstur SM. 50-year trends in smoking-related mortality in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368:351–364. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1211127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner FA, Sheikhattari P, Buccheri J, Gunning M, Bleich L, Schutzman C. A community-based participatory research on smoking cessation intervention for urban communities. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2016;27:35–50. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2016.0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Bernstein E. Empowerment education: Freire’s ideas adapted to health education. Health Education Quarterly. 1988;15:379–394. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior. 1997;24:369–387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC. Photovoice: A participatory action research strategy applied to women’s health. Journal of Women’s Health. 1999;8:185–192. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1999.8.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC. Youth participation in photovoice as a strategy for community change. Journal of Community Practice. 2006;14:147–161. doi: 10.1300/J125v14n01_09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winkleby MA, Feighery E, Dunn M, Kole S, Ahn D, Killen JD. Effects of an advocacy intervention to reduce smoking among teenagers. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:269–275. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate RL, Busolo DS. A qualitative study on Canadian youth’s perspectives of peers who smoke: An opportunity for health promotion. BMC Public Health. 2015;15 doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2683-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]