Abstract

Background:

To improve measures of monthly tobacco cigarette smoking among non-daily smokers, predictive of future non-daily monthly and daily smoking.

Methods:

Data from United States National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, tracking adolescents, ages 12–21, over 14 years were analyzed. At baseline, 6501 adolescents were assessed; 5114 individuals provided data at waves 1 and 4. Baseline past 30-day non-daily smokers were classified using quantity-frequency measures: cigarettes smoked/day by number of days smoked in the past 30 days.

Results:

Three categories of past 30-day non-daily smokers emerged using cigarettes/month (low:1–5, moderate: 6–60, high: 61+) and predicted past 30-day smoking at follow-up (low: 44.5%, moderate: 60.0%, high: 77.0%, versus 74.2% daily smokers; rT= −0.2319, p < 0.001). Two categories of non-smokers plus low, moderate and high categories of non-daily smokers made up a five-category non-daily smoking index (NDSI). High NDSI (61+ cigs/mo.) and daily smokers were equally likely to be smoking 14 years later (High NDSI OR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.53–1.80 [daily as reference]). Low (1–5 cigs/mo.) and moderate (6–60 cigs/mo.) NDSI were distinctly different from high NDSI, but similar to one another (OR = 0.21, 95% CI = 0.15–0.29 and OR = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.14–0.34, respectively) when estimating future monthly smoking. Among those smoking at both waves, wave 1 non-daily smokers, overall, were less likely than wave 1 daily smokers to be smoking daily 14 years later.

Conclusions:

Non-daily smokers smoking over three packs/month were as likely as daily smokers to be smoking 14-years later. Lower levels of non-daily smoking (at ages 12–21) predicted lower likelihood of future monthly smoking. In terms of surveillance and cessation interventions, high NDSI smokers might be treated similar to daily smokers.

Keywords: Non-daily smoking, Tobacco cigarette smoking, Adolescents, Future smoking, Longitudinal

1. Introduction

Monthly and daily measures of tobacco cigarette smoking have been fundamental to United States surveillance (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CCD), 2013; Johnston et al., 2014; Kvaavik et al., 2014). When reporting U.S. trends in current cigarette smoking among youth and adults, smoking prevalence is measured based upon self-reported tobacco use in the past 30-days, which includes both daily and non-daily smong adults compared with those in their 30s and beyond (Okuyemi et al., 2002; Owen et al., 1995) and non-daily smoking has been shown to progress into daily smoking (Gilpin et al., 2001; Robertson et al., 2015). Public health and policy considerations have tended to focus on daily smokers in part due to health consequences (Benowitz and Henningfield, 1994; Coggins et al., 2009; Okuyemi et al., 2002; Shiffman, 1989; Shiffman et al., 1994). Although there are likely health risks associated with lower levels of smoking, the greatest increases in mortality are observed among daily cigarette smokers and among those smoking more than one pack per day (Bjartveit and Tverdal, 2005; Teo et al., 2006).

Smokers consuming low numbers of cigarettes are not well defined; they have been referred to as “chippers”, “low-rate”, “occasional”, “intermittent”, “light”, and “non-daily smokers” (Hennrikus et al., 1996; Husten et al., 1998; Owen et al., 1995; Shiffman, 1989; Wortley et al., 2003). National surveys define “non-daily” smoking in a variety of ways; smoking weekly or less than weekly [but not daily], having smoked at least 100 cigarettes and currently smoking on some days (CCD, 1994, 2011). U.S. adult data also indicate that the percentage of non-daily smokers has been increasing over the years and the proportion of non-daily smoking remains substantial (CCD, 1996; Jamal et al., 2014). Annual surveys of U.S. 12th grade students from 1975 to 2013 showed a 29% decrease in daily smoking, including a 40% decrease in those smoking 10+ cigarettes/day (Kozlowski and Giovino, 2014). Observations that monthly smokers in the U.S. are increasingly reporting non-daily use is one indication that the current smoking population is softening, rather than hardening and call for better measures of monthly smoking (Kozlowski and Giovino, 2014; Warner, 2015). Further, decreases in cigarette smoking among U.S. adolescents are larger for those reporting smoking ≥½ pack of cigarettes daily vs. measuring life time smoking, suggesting the need for more precise measures of monthly smoking (Warner, 2015).

This study sought to classify non-daily smokers with the development of a measure created from a quantity-frequency (QF) measure. The QF measure is a product of the number of cigarettes smoked per day (CPD) on the days smoked and the total reported number of days cigarettes were smoked in the past 30 days, using data from the United States National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) survey (Harris and Udry, 1994). Using a QF measure, non-daily smokers were reclassified into subgroups in order to answer several questions: (1) To what extent does a reclassification predict two criterion variables: monthly (past 30-day smoking) and daily smoking at a 14-year follow-up?(2) Is it possible to identify a subset of non-daily monthly smokers who are similar to daily smokers in terms of future (14 years later) monthly and daily smoking? (3) Is there a group of low-level, non-daily monthly smokers who are similar to those who have ever smoked cigarettes but have not smoked in the past 30-days when predicting smoking 14 years later? (4) How do subgroups of non-daily smokers compare to those who have never smoked in terms of monthly smoking when measured 14 years after initial assessment?

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

The sample included data from waves 1 and 4 of the United States National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). Add Health is a nationally representative interviewer administered longitudinal sample of U.S. adolescents in grades 7 through 12 during the 1994–95 school year (n = 6501); respondents were 12–21 years old at initial assessment. This cohort was followed through young-adulthood and the most recent follow-up, wave 4, occurred in 2008 (ages 25–34); 5114 individuals provided data from both waves 1 and 4 (78.7% of original cohort)

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographic variables.

Age was a continuous variable calculated using birth date of respondent, sex was binary and reported by the interviewer when the in-home questionnaire was administered at wave 1. Race, a categorical variable, was self-reported as White, Black or African American, American Indian or Native American, Asian/Pacific Islander, or other. Grade in school was continuous (grade 7 through 12) and was recorded at wave 1 interview; grade was recoded into three categories: 7th and 8th, 9th and 10th, 11th and 12th grades. Analyses controlled for demographic variables discussed here.

2.2.2. Tobacco-related variables

2.2.2.1. Age at first cigarette.

“How old were you when you smoked a whole cigarette for the first time?”

2.2.2.2. Cigarette smoking status.

Current smokers (monthly smokers) at wave 1 reported having smoked cigarettes on at least one day in the past 30 days: “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes?” (Responses ranged from 0 to 30 days). The number of cigarettes smoked per day, was a discrete measure: “During the past 30 days, on the days that you smoked, how many cigarettes per day (CPD) did you smoke?” Non-daily smokers included those who reported that they had ever smoked a whole cigarette in their life but had not smoked in the past 30 days or, smoked between 1 and 29 days in the past 30 days; daily smokers smoked on all 30 days. Never smokers reported never smoking an entire cigarette in their life

2.2.2.3. Quantity-frequency (QF) for monthly smoking.

A QF measure was created by multiplying CPD by the number of days smoked during the past 30 days. Monthly QF was represented by cigarettes per month (CPM)

2.2.2.4. “Regular” daily cigarette smokers. Assessed at wave 1:

“Have you ever smoked cigarettes regularly, that is, at least 1 cigarette every day for 30 days?” Responses were binary (yes/no)

2.2.2.5. Recent quit attempt. Assessed at wave 1:

“During the past 6 months, have you tried to quit smoking cigarettes?” Responses were binary (yes/no)/

2.2.2.6. Monthly smoking 14 years later (future monthly smoking).

Determined among wave 1 respondents who were retained at wave 4; respondents were monthly smokers if, at wave 4, they had smoked cigarettes on any days in the previous 30 days

2.2.2.7. Daily smoking 14 years later (future daily smoking).

Respondents were daily smokers if, at wave 4, they had smoked on all days in the past 30. Those not classified as daily smokers were grouped together

2.2.2.8. Smokeless tobacco use.

Assessed at wave 1 with the question “During the past 30 days, on how many days have you used chewing tobacco or snuff?” Responses were continuous but were then recoded as a dichotomous variable (no use/any use in the past 30 days)

2.3. Statistical procedures

After adjusting for the sampling design and clustering effects (Chantala, 2006), frequencies were reanalyzed to identify proportions for demographic characteristics, smoking status, and smokeless tobacco use. Means and standard errors were calculated for age at both waves and monthly cigarettes smoked at wave 4. Logistic regression models were analyzed to estimate the odds of both past 30-day smoking and daily smoking at 14-year follow-up. All analyses were estimated using sampling weights correcting for the sampling design and any nonresponse (Chantala, 2006). Estimates of standard errors, variances and confidence intervals were adjusted for clustering at the school level (Chantala, 2006). All analyses were completed using Stata version 13 (Statacorp, 2013) 2.3.1. Non-daily monthly and daily smoking analyses. Non-daily monthly (past 30-day) smokers were categorized based on data from waves 1 and 4. Categories were based on logistic regression analyses using the wave 1 QF measure of monthly smoking and led to the development of three categories to classify past 30-day non-daily smokers and demonstrate a linear trend predicting monthly smoking 14 years later. The QF measure for current non-daily smokers was also divided into tertiles (1–5, 6–36, >36 cigarettes per month) and categories were adjusted to better represent cigarette pack size. Based on these divisions, the non-daily categories were low: 1–5 cigarettes per month (CPM), moderate: 6–60 CPM and high: 61+ CPM. These non-daily monthly smoking categories (low, moderate and high) were cross-tabulated with monthly smoking 14 years later and also with daily smoking 14 years later (wave 4 measures) and 95% confidence intervals were computed. To test for homogeneity within each of these three groups of non-daily monthly smokers, a median split of each sub-category (creating a low and a high split for each) was completed; chi-square tests and 95% confidence intervals tested for significant differences between each median split. To further investigate non-daily monthly smokers, cross-tabulations explored the relationship between sub-category and ever regular smoking (assessed at wave 1) and whether or not a quit attempt was made in the past six months prior to the wave 1 survey. The categorization of smokers at wave 4 based on their wave 1 smoking category was analyzed using cross-tabulations and 95% CI’s (see Figs. 1 and 2)

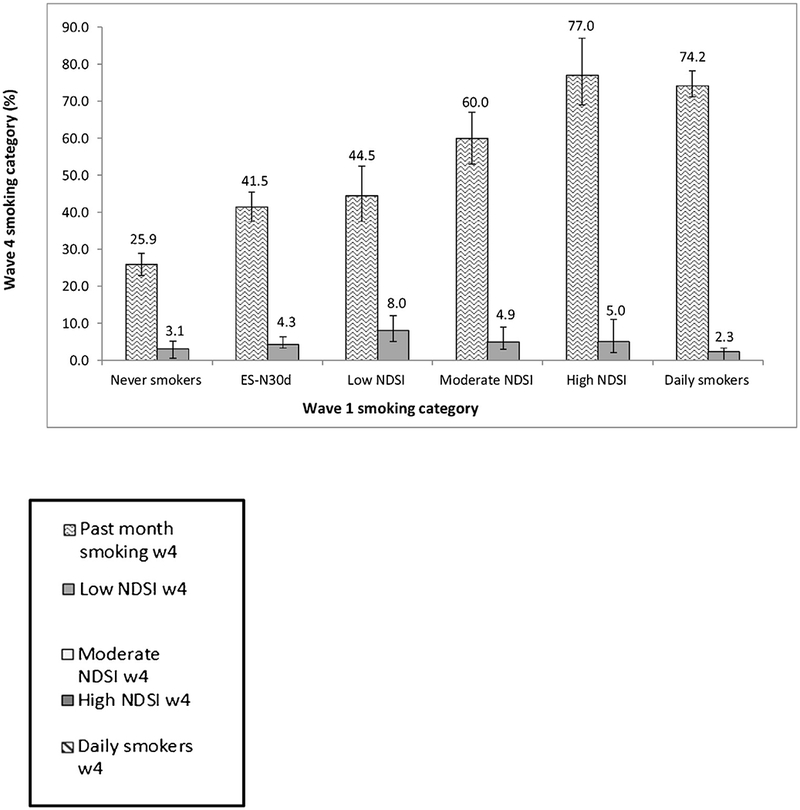

Fig. 1.

Percentage of wave 4 past month smoking or low-level monthly smoking. Percentages of wave 4 (14 years later) monthly cigarette smoking and low monthly smoking (low NDSI) are shown, based on smoking categorization at wave 1; data from United States National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), 1994–2008(1).

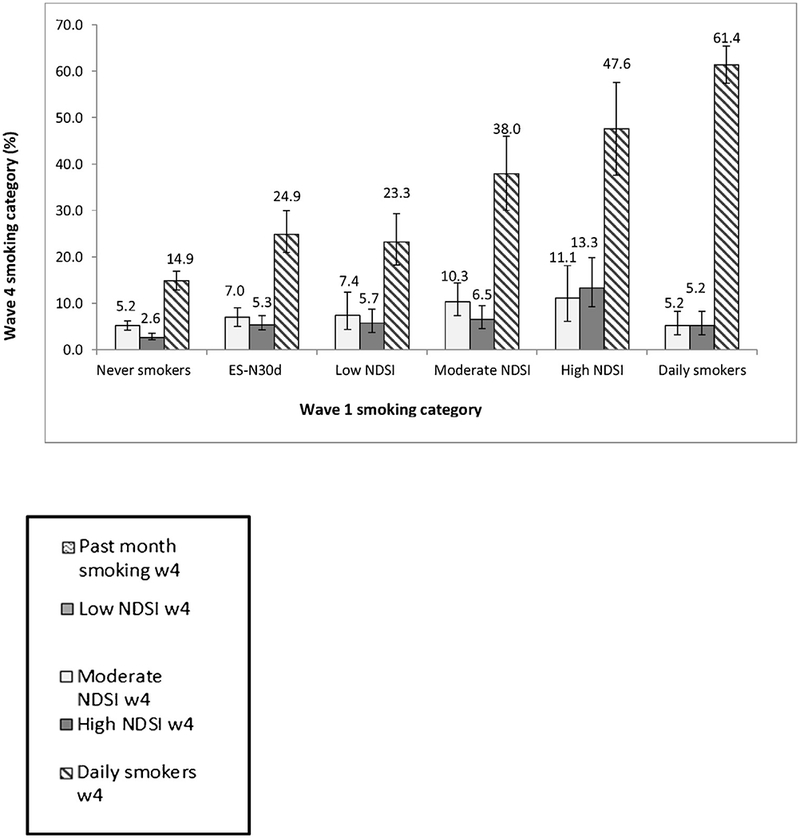

Fig. 2.

Percentages of wave 4 daily, moderate and high NDSI smokers. Percentages of wave 4 (14 years later) moderate and high monthly smoking, as well as percentages of daily smoking, based on smoking categorization at wave 1; data from United States National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), 1994–2008 (1).

2.3.2. Non-daily smoking index (NDSI).

Daily smokers were the comparison group when investigating non-daily monthly smoker sub-categories. A non-daily smoking index (NDSI) was then created; NDSI combines two groups of non-monthly smokers (those who have never smoked a cigarette in their life and those who have ever smoked a cigarette but have not done so in the past 30 days) with the previously described three category measure (low/1–5 CPM, moderate/6–60 CPM, and high/61+ CPM). We include two groups of non-current (past 30-day) smokers: never smokers and those who ever smoked but not in the past 30 days as part of the index because these groups are part of “non-daily” smokers as a whole, more specifically, non-daily smokers who have either never smoked a cigarette or those who are not currently smoking. Therefore, the NDSI is a five-category scale ranging from never smokers to a “high” level of current non-daily smokers in order to examine what happens to these five groups over time in this study.

The five-category NDSI is made up of the following groups: never smoked a whole cigarette, ever smoked a whole cigarette but not past 30-day (ES-N30d), 1–5 cigarettes/month (low NDSI), 6–60 cigarettes/month (moderate NDSI), and 61+ cigarettes/month (high NDSI). The NDSI was analyzed in two separate logistic regression models using the two criterion variables to predict the odds of monthly smoking 14 years later and odds of daily smoking 14 years later. A third logistic regression model was analyzed to predict daily smoking among those who were smoking at both waves 1 and 4

3. Results

A total of 5114 individuals provided data at both waves 1 and 4(21.34% lost to follow-up). Differences between those lost to follow-up and those who completed both waves of data collection were tested using Chi-square analyses; there were no significant differences at wave 1 between the two groups in terms of grade in school, sex, wave 1 level of smoking, age first smoked a whole cigarette or past 30-day use of smokeless tobacco. At wave 1, there were 1593 (24.5%; 1003 non-daily and 590 daily smokers) current smokers out of a total of 6504 valid cases (24.5%). There were 796 (15.9%) respondents who were current smokers at both waves 1 and 4, and 453 (9.0%) current smokers at wave 1 who were not monthly smokers when measured at wave 4.

Mean age at wave 1 was 16.0 years (SE = 0.12), and 29.0 years (SE = 0.12) at waves 1 and 4, respectively. Demographic variables were adjusted for survey weights and sampling design: the sample was 51.0% male (unadjusted n = 2353), 71.6% white (unadjusted n = 4038), grade in school was evenly distributed (7th/8th grade:34.0%, 9th and 10th grade: 34.2%, and 11th and 12th grade: 31.8%), and the majority of the sample (92.7%) at wave 1 had not used smokeless tobacco in the past 30 days

3.1. Ever regular smoking and age of first cigarette

Mean age of first cigarette smoked (13–14 years old) did not differ significantly by NDSI category. Among ever regular smokers, low NDSI smokers were significantly more likely to have tried to quit in the 6 months prior to wave 1 compared with high NDSI smokers (75.4% vs. 53.1%, p < 0.05), and with daily smokers (75.4% vs. 51.2%, p < 0.05)

3.2. Quantity-frequency (QF) measure

The quantity-frequency (QF) measure of cigarettes per month (CPM) ranged from 1 to 810 CPM among non-daily smokers and 30–1800 CPM among daily smokers. In the context of the full-scale QF measure, CPD and days smoked per month were correlated [H9251] = 0.52. Both CPD (OR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.94–0.99) and number of days smoked (OR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.95–0.98) are predictors of the outcome (wave 4 past 30-day smoking). Prior to being categorized, the non-daily QF measure was analyzed in a logistic regression model and was also predictive of having smoked in the past 30-days at wave 4 (OR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.53–1.80)

3.3. Past 30-day (monthly) smoking 14 years later

To compare categories of non-daily monthly smokers with daily smokers, three sub-categories of non-daily monthly smokers were used: low (1–5 cigarettes/month, 36.3%), moderate (6–60 cigarettes/month, 42.1%) and high (61+ cigarettes/month, 21.6%). Non-daily monthly categories were homogenous; when each category was divided in half using a median split we found no reliable difference between the high and low division for each particular category (low: p = 0.123, moderate: p = 0.932, high: p = 0.098).

Results from the logistic regression model estimating odds of future monthly smoking (adjusted for grade in school, race, sex and past 30-day smokeless tobacco use) are shown in Table 1. In general, non-daily monthly smokers, compared with daily smokers, had decreased odds of reporting monthly smoking 14 years later, with the exception of high NDSI smokers, who demonstrated similar odds to daily smokers and were most likely to be past-month smokers 14 years later. When observing lower level NDSI smokers (never smokers through moderate NDSI smokers) those who smoked fewer cigarettes per month were least likely to have smoked in the past 30 days 14 years later, compared with daily smokers at wave 1 who were the most likely to be past-month smokers at wave 4 (Table 1). Fig. 1 shows the percentages of monthly smoking (ES-N30d) and low NDSI at wave 4, based on wave 1 smoking category. There was a linear relationship among the non-daily monthly smokers (monthly smoking: low NDSI: 44.5%, moderate NDSI:60.0%, high NDSI: 77.0.0%) in relation to likelihood of no monthly smoking measured 14 years later (Kendall’s Tau-b [r[H9270]] = 0.3355, p < 0.001). High NDSI smokers and daily smokers were not significantly different from one another when estimating likelihood of future monthly smoking (high NDSI: OR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.53–1.80).

Table 1.

Odds ratios of monthly and of daily smoking at 14 year follow up, by original Non-Daily Smoking Index (NDSI) and selected demographic categories

| Baseline characteristics | Smoking category at 14year follow-up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| monthly smoking | daily smoking | |||||

| N (%) | OR | 95% CI | N (%) | OR | 95% CI | |

| NDSI wave 1 | ||||||

| Never smoked a whole cigarette | 675 (25.9) | 0.08** | 0.06−0.11 | 371 (14.9) | 0.08** | 0.06−0.10 |

| ES-N30d | 344 (41.5) | 0.21** | 0.15−0.29 | 202 (24.9) | 0.18** | 0.13−0.24 |

| Low NDSI | 131 (44.5) | 0.22** | 0.14−0.34 | 71 (23.3) | 0.16** | 0.11−0.24 |

| Moderate NDSI | 195 (60.0) | 0.45** | 0.29−0.58 | 118 (38.0) | 0.36** | 0.25−0.51 |

| High NDSI | 123(77.0) | 0.97 | 0.53−1.80 | 78 (47.6) | 0.52** | 0.33−0.81 |

| Daily smokers | 347 (74.2) | 1.00 | ref | 282 (61.4) | 1.00 | ref |

| Grade | ||||||

| 7/8th | 610 (43.7) | 1.00 | ref | 384 (28.1) | 1.00 | ref |

| 9/10th | 624 (37.6) | 0.54** | 0.44−0.66 | 381(23.2) | 0.53** | 0.43−0.67 |

| 11/12th | 544 (34.5) | 0.37** | 0.30−0.45 | 332 (22.0) | 0.39** | 0.31−0.49 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1264 (40.5) | 1.00 | ref | 838(27.2) | 1.00 | ref |

| Black/African American | 335 (33.4) | 1.17 | 0.86−1.59 | 178 (16.7) | 0.88 | 0.67−1.14 |

| America Indian/Native American | 65 (45.3) | 1.30 | 0.84−2.02 | 37(31.9) | 1.30 | 0.73−2.29 |

| Asian | 49 (29.7) | 0.81 | 0.51−1.29 | 25 (15.9) | 0.66 | 0.41−1.04 |

| Other | 97 (33.0) | 0.93 | 0.68−1.28 | 43 (14.7) | 0.53* | 0.37−0.77 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 957 (43.4) | 1.00 | ref | 579 (26.7) | 1.00 | ref |

| Female | 858 (34.2) | 0.63* | 0.54−0.74 | 543 (22.4) | 0.75* | 0.64−0.88 |

| Past 30-day smokeless tobacco use | ||||||

| None | 1602 (37.2) | 1.00 | ref | 997 (23.9) | 1.00 | ref |

| Any | 182 (57.2) | 1.35 | 0.99−1.83 | 109 (33.6) | 0.94 | 0.67−1.32 |

Note: N reflects the sample size prior to survey weighting and design effect adjustment; percentages reflect the proportion of each category who were monthly or who were daily smokers 14 years later, after adjusting for survey weights and design effects. ES-N30d = Ever smoked a whole cigarette, but not in the past 30-days. Data from the United States National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) survey, 1994–2008 (1).

p < 0.05.

p < 0.001.

Compared with ES-N30d smokers, non-daily monthly smokers, as a whole, had greater odds of monthly smoking 14 years later; however, low NDSI smokers were the exception, and were very similar to ES-N30d smokers (Table 1). Figs. 1 and 2 also show the similarities between less than monthly and low NDSI smokers; when looking at monthly smoking 14 years later, these categories were nearly identical. This similarity between these low-level groups is again displayed in Fig. 2, which shows the percentage of moderate, high and daily smokers at wave 4, grouped by wave 1 category. Among wave 1 ever smokers, ES-N30d smokers had the lowest odds of monthly smoking at wave 4 (Table 1)

3.4. Daily smoking 14 years later

Results from the logistic regression model estimating odds of future daily smoking are also shown in Table 1 (adjusted for grade in school, race, sex and past 30-day smokeless tobacco use). As monthly smoking category increases, the odds of daily smoking increase (never: OR = 0.08, 95% CI = 0.06–0.10, ES-N30d OR = 0.18, 95% CI = 0.13–0.24, low NDSI: OR = 0.16, 95% CI = 0.11–0.24; moderate NDSI: OR = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.25–0.51; high NDSI: OR = 0.52, 95% CI = 0.33–0.81; daily smokers as the reference group). Daily smokers had about twice the odds of daily smoking 14 years later compared with high NDSI smokers. ES-N30d and low NDSI smokers were not significantly different from one another in terms of pre dicting future daily smoking and both groups had twice the odds of future daily smoking compared with never smokers.

Among those who had smoked any amount in the past 30-days at wave 4 (n = 1858), there was only 1 smoker who had never smoked a cigarette at wave 1 (of the 3752 “never” smokers) who moved on to being a daily smoker at wave 4. 52.3% of wave 1 low NDSI, 63.7% of wave 1 moderate NDSI and 61.8% of wave 1 high NDSI smokers were smoking daily at wave 4 (none of which were significantly different from one another) and 82.9% of wave 1 daily smokers were daily smokers at wave 4. Results from the logistic regression examining future daily smoking among those who were smoking at both waves 1 and 4 indicate that all groups of wave 1 non-daily smokers are about one-third as likely (compared with wave 1 daily smokers) to be daily smokers at wave 4 (wave 1 low NDSI OR = 0.23, 95% CI = 0.14–0.37, moderate NDSI OR = 0.37, 95% CI = 0.24–0.55, high NDSI OR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.19–0.55; daily smokers as the reference group)

4. Discussion

4.1. Non-daily monthly smoking categories

This analysis of U.S. adolescent smokers suggests that non-daily monthly adolescent smokers could be categorized into three groups (low, moderate and high), that offer practical cut-offs for monthly smoking categories and which predict monthly smoking 14 years later. Although tertiles could be used as a guide, it may be more constructive to apply the described low, moderate and high categories of non-daily smokers across different samples since a tertile-based measure will be influenced by the composition of each sample. We noted that there was homogeneity within non-daily monthly smoking categories (no differences found between upper and lower halves of each category) in predicting future monthly smoking, further supporting these divisions.

4.2. non-daily smoking index (NDSI)

After creating three categories that allowed for non-daily monthly smokers to be compared with daily smokers when predicting future monthly smoking and future daily smoking, we considered whether there was a subset of low-level monthly smokers who were similar to those who have ever smoked, but were not monthly smokers. The NDSI is an original measure designed to be inclusive of all non-daily smokers, including those who ever smoked but not in the past 30 days (ES-N30d) and those who have never smoked

4.3. Changes in non-daily smokers over time and similarities between high NDSI and daily smokers

A study following young adults in New Zealand for 17 years found that non-daily smokers at age 21 were significantly greater odds of becoming daily smokers 17 years later (compared with non-smokers) (Robertson et al., 2015). Similarly, among our sample, adolescents (grades 7–12) who smoked on a non-daily basis, compared with never smokers, were more likely to have smoked in the past 30-days and were more likely to smoke daily when followed-up 14 years later. Despite non-daily smokers being more likely to smoke in the future, compared with never smokers, these occasional or non-daily smokers are a heterogenous group and it is important to examine differences among sub-groups of non-daily smokers (Edwards et al., 2010).

A large percentage of daily smokers at wave 1 fell within the same range of CPM reported by non-daily smokers in the high NDSI group, indicating that while non-daily and daily smokers are characterized differently, CPM are similar among these groups, which may reflect different factors motivating cigarette use. Further, high NDSI smokers were nearly indistinguishable from daily smokers in terms of future monthly smoking, supporting the consideration that higher level non-daily smokers (high NDSI) are similar to daily smokers. Non-daily smokers with high CPM (high NDSI) act just as daily smokers do in predicting smoking 14 years later, despite the expectation that some believe dependence would require one to be a daily smoker (Berg et al., 2009; Hajek et al., 1995; Harris et al., 2008; Levinson et al., 2007). The high NDSI category is comprised of a wide range of smokers (those smoking 61–810 cigarettes per month). From a prevention and surveillance standpoint, it is better to be overly inclusive, rather than excluding some smokers, espe cially when concluding that these high level smokers should be treated similarly to daily smokers.

Because daily smokers made up 68.5% of all smokers at wave 4, we were interested in examining the effects of wave 1 NDSI on future daily smoking among only those smoking at both waves 1 and 4. Wave 1 daily smokers were more likely than wave 1 non-daily smokers to be smoking daily 14 years later, which is also demonstrated in the analysis including all wave 1 smokers who were followed-up at wave 4 (regardless of smoking status at wave 4) (see Table 1); this full analysis allows for better discrimination of categories of wave 1 NDSI in predicting future daily smoking. Wave 1 ES-N30d smokers (ever tried but had not smoked in past 30 days) and low NDSI smokers (1–5 cigs/mo.) were both twice as likely as wave 1 never smokers to be smoking daily 14 years later; these groups were not significantly different from one another in predicting daily smoking. Wave 1 moderate and high NDSI smokers were also similar to one another when predicting future daily smoking; however, moderate and high NDSI smokers were different from each of the lower NDSI categories (never, ES-N30d and low). Said differently, those smoking above the 1–5 cigarettes per month (moderate NDSI and above) threshold are more likely to be future daily smokers compared with wave 1 never smokers, and those who smoked less frequently (≤5 cigarettes in the past 30-days at wave 1). Despite that wave 1 high NDSI smokers and daily smokers are significantly different when predicting future daily smoking, the similarity found between these two groups predicting future monthly smoking indicates an important similarity between the two groups

4.4. Similarities between ES-N30d and low NDSI smokers

Low NDSI smokers were not just beginning use of cigarettes when the survey was given: average age of first cigarette smoked was nearly three years younger than the current average age of those smoking 1–5 CPM (low NDSI smokers) at wave 1. Given this information, low NDSI smokers were a group of particular interest. Just as high NDSI and daily smokers were indistinguishable from one another; low NDSI and ES-N30d (ever, but not past 30-day) smokers similarly shared this relationship. While ES-N30d smokers and low NDSI smokers are different from higher level smokers (both high NDSI and daily smokers), in terms of both daily and monthly smoking 14 years later, the similarity between these two low-level groups when predicting future monthly and daily smoking could serve as an argument for a combined group. When investigating future monthly smoking, we observed marked differences in future monthly smoking between ES-N30d smokers and never smokers on the baseline survey. This finding suggests that adolescents who are not monthly smokers, but have tried any amount of cigarettes in their lifetime, are at increased risk of becoming smokers in the future, compared with their never-smoking counterparts. Those who never smoked cigarettes were least likely to smoke in the future. However, given that in 2013, nearly 15% of adolescents had tried smoking by eighth grade (Johnston et al., 2014), prevention programs should not only aid young smokers in quitting, but give much needed attention to non-daily smokers in an effort to prevent low-level adolescent smokers from becoming heavier smokers as adults.

Some limitations of this study are worth noting. Not all students who smoked may have reported being a smoker at wave 1; a U.S. study found those aged 12–17 years old displayed a 3% under-reporting rate when compared with serum cotinine levels, although serum cotinine may not be a perfect biomarker when measuring low-level smokers due to its short half-life (Caraballo et al., 2004) and lack of specificity to cigarette smoking; moreover, it is unclear whether underreporting has varied over time. The Add Health survey did not collect biochemical markers to validate this finding, however, self-report data may be just as accurate (Tennekoon and Rosenman, 2015). Other tobacco use in this study includes chewing tobacco and snuff use only, as use of other products was not collected.

There are several strengths in using the Add Health dataset despite that the last wave analyzed was in 2008. The data set is a U.S. nationally representative longitudinal dataset, which followed adolescents in grades 7–12 over a 14-year period. Wave 1 includes data on an age group that is more inclined to experiment with cigarette smoking, thus a 14-year follow-up allowed for the assessment of future smoking behavior among a group at-risk to future cigarette smoking. Other strengths include the collection of both CPD and number of days smoked as continuous measures; other surveys (Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey, YRBS) contain categorical measures which create methodological challenges (McGinley and Curran, 2014). Continuous QF measures for all non-cigarette nicotine/tobacco products in national surveys could be beneficial in improving surveillance of product use.

A non-daily smoking index (NDSI) may be a practical classification which is inclusive of all non-daily smokers. Similarly simple measures have been shown to be very useful in measuring heaviness of daily smoking (Heatherton et al., 1989). Based on evidence that, in the U.S., the current youth smoking population is softening (Kozlowski and Giovino, 2014; Warner, 2015), the introduction of a more precise measure to categorize smokers is needed to better describe non-daily smokers

Role of funding source

University of Pennsylvania, Tobacco Centers of Regulatory Science (TCORS). Grant number: P50-CA-179546–01

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Other than Dr. Mahoney, the other co-authors have no financial interest in this study and no conflicts of interests to disclose. Dr. Mahoney has previously served as a consultant to Pfizer regarding Chantix® and the topic of smoking cessation, has received peer-reviewed research funding from Pfizer’s Global Research Award for Nicotine Dependence (GRAND), has conducted smoking cessation clinical trials, and has served as a paid expert witness in litigation against the tobacco industry; he also currently serves as the Medical Director for the NYS Smokers Quitline

References

- Benowitz NL, Henningfield JE, 1994. Establishing a nicotine threshold for addiction. The implications for tobacco regulation. N. Engl. J. Med. 331, 123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CJ, Lust KA, Sanem JR, Kirch MA, Rudie M, Ehlinger E, Ahluwalia JS, An LC, 2009. Smoker self-identification versus recent smoking among college students. Am. J. Prev. Med. 36, 333–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjartveit K, Tverdal A, 2005. Health consequences of smoking 1–4 cigarettes per day. Tob. Control 14, 315–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1994. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 1992, and changes in the definition of current cigarette smoking. MMWR 43, 342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1996. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 1994. MMWR 45, 588.9132579 [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010. Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2000–2009. MMWR 59, 1063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011. Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years—United States, 2005–2010. MMWR 60,1207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013. Tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011 and 2012. MMWR 62, 893–897. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caraballo RS, Giovino GA, Pechacek TF, 2004. Self-reported cigarette smoking vs. serum cotinine among US adolescents. Nicotine Tob. Res. 6, 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantala K, 2006. Guidelines For Analyzing Add Health Data Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC. [Google Scholar]

- Coggins CR, Murrelle EL, Carchman RA, Heidbreder C, 2009. Light and intermittent cigarette smokers: a review (1989–2009). Psychopharmacology (Berl) 207, 343–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards SA, Bondy SJ, Kowgier M, McDonald PW, Cohen JE, 2010. Are occasional smokers a heterogeneous group? An exploratory study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 12, 1195–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin E, Emery S, Farkas A, Distefan J, White M, Pierce J, 2001. The California Tobacco Control Program: A Decade of Progress, Results from the California Tobacco Surveys, 1990–1998. University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, pp. 1–291. [Google Scholar]

- Hajek P, West R, Wilson J, 1995. Regular smokers, lifetime very light smokers, and reduced smokers: comparison of psychosocial and smoking characteristics in women. Health Psychol. 14, 195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Udry JR, 1994. National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health). Waves I & II, 1996:2001–2002. [Google Scholar]

- Harris JB, Schwartz SM, Thompson B, 2008. Characteristics associated with self-identification as a regular smoker and desire to quit among college students who smoke cigarettes. Nicotine Tob. Res. 10, 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Rickert W, Robinson J, 1989Measuring the heaviness of smoking: using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Br. J. Addict. 84, 791–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennrikus DJ, Jeffery RW, Lando HA, 1996. Occasional smoking in a Minnesota working population. Am. J. Public Health 86, 1260–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husten CG, McCarty MC, Giovino GA, Chrismon JH, Zhu B, 1998. Intermittent smokers: a descriptive analysis of persons who have never smoked daily. Am. J. Public Health 88, 86–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, Agaku IT, O’Connor E, King BA, Kenemer JB, Neff L, 2014. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2013. MMWR 63, 1108–1112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA, 2014. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results On Drug Use, 1975–2013: Volume II, College Students And Adults Ages 19–55. Institute For Social Research, The University Of Michigan, Ann Arbor. [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Kawkins J, Harris WA, Chyen D, 2014. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2013. MMWR 63 (Suppl.4), 1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski LT, Giovino GA, 2014. Softening of monthly cigarette use in youth and the need to harden measures in surveillance. Prev. Med. Rep. 1, 53–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvaavik E, von Soest T, Pedersen W, 2014. Nondaily smoking: a population-based, longitudinal study of stability and predictors. BMC Public Health 14, 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson AH, Campo S, Gascoigne J, Jolly O, Zakharyan A, Tran ZV, 2007. Smoking, but not smokers: identity among college students who smoke cigarettes. Nicotine Tob. Res. 9, 845–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinley JS, Curran PJ, 2014. Validity concerns with multiplying ordinal items defined by binned counts: an application to a quantity-frequency measure of alcohol use. Methodology (Gott.) 10, 108–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuyemi KS, Harris KJ, Scheibmeir M, Choi WS, Powell J, Ahluwalia JS 2002. Light smokers: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob. Res. 4 (Suppl.2), S103–S112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen N, Kent P, Wakefield M, Roberts L, 1995. Low-rate smokers. Prev. Med. 24, 80–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson L, Iosua E, McGee R, Hancox RJ, 2015. Non-daily, low-rate daily and high-rate daily smoking in young adults: a 17 year follow-up Nicotine Tob. Res, epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Paty JA, Kassel JD, Gnys M, Zettler-Segal M, 1994. Smoking behavior and smoking history of tobacco chippers. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, 1989. Tobacco chippers—individual differences in tobacco dependence. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 97, 539–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statacorp, 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13 StataCorp LP, College Station, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Surgeon General, 2014. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

- Tennekoon V, Rosenman R, 2015. The pot calling the kettle black? A comparison of measures of current tobacco use. Appl. Econ. 47, 431–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo KK, Ounpuu S, Hawken S, Pandey M, Valentin V, Hunt D, Diaz R, Rashed W, Freeman R, Jiang L, Zhang X, Yusuf S, INTERHEART Study Investigators, 2006. Tobacco use and risk of myocardial infarction in 52 countries in the INTERHEART study: a case-control study. Lancet 368, 647–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner KE, 2015. The remarkable decrease in cigarette smoking by American youth: further evidence. Prev. Med. Rep. 2, 259–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortley PM, Husten CG, Trosclair A, Chrismon J, Pederson LL, 2003. Nondaily smokers: a descriptive analysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 5, 755–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]