Abstract

Incidence of post-donation hypertension, risk factors associated with its development and impact of type of treatment received on renal outcomes were determined in 3700 kidney donors. Using Cox proportional hazard model, adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for cardiovascular disease (CVD), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60, <45, <30 mL/min/1.73m2, end stage renal disease (ESRD) and death in hypertensive donors were determined. After a mean (SD) of 16.6 (11.9) years of follow-up, 1126 (26.8%) donors developed hypertension and 894 were receiving anti-hypertensive medications. Hypertension developed in 4%, 10% and 51% at 5, 10, and 40 years, respectively and was associated with proteinuria, eGFR < 30, 45 and 60 mL/min/1.73m2, CVD and death. Blood pressure was <140/90 mmHg at last follow-up in 75% of hypertensive donors. Use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (compared to other antihypertensive agents) was associated with lower risk for eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73m2, HR 0.64 (95% CI 0.45–0.9), p = 0.01 and also less ESRD; HR 0.03 (95% CI 0.001–0.20), p = 0.004. In this predominantly Caucasian cohort, hypertension is common after donation, well controlled in the majority of donors and factors associated with its development are similar to those in the general population.

Introduction

Reduction in renal mass and function are associated with a progressive increase in blood pressure and the development of systemic hypertension in animal models and humans with low nephron number (1, 2).

Studies addressing changes in blood pressure and the development of new onset hypertension following kidney donation have been generally small and suffered from short follow-up. One meta-analysis reported that systolic blood pressure (SBP) increased by 1.1 mmHg per decade, while diastolic blood pressure (DBP) did not change and there was no difference in the prevalence of hypertension between donors and controls (3). This study included donors (60%) and non-donors who underwent uninephrectomy for disease or had renal agenesis (3). In a meta-analysis that specifically addressed hypertension in kidney donors. Boudville et al. reported that mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures were 6 and 4 mmHg higher in kidney donors than in controls (4). The risk of incident hypertension, however, could not be accurately determined due to the inability to pool results from the 6 studies comparing donor to controls due to statistical heterogeneity (4). Understanding hypertension after donation is important, as it appears to be a leading cause of ESRD, particularly, late after donation (5, 6). Attributing ESRD to hypertension is problematic as almost none of these cases are biopsy proven. This is very important as the proportion of ESRD attributed to hypertension is overestimated as evidenced from case series where patients whose ESRD is “caused” by hypertension do not exhibit histological pattern of benign nephrosclerosis (7). Moreover, the evidence linking hypertension to CKD is far from convincing as hypertension may actually be a result of underlying kidney disease rather than causing it (8). Very little data exist on how well hypertension is treated in donors and with what agents. This is highly, as most clinicians believe that agents that interrupt the renin-angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) would be beneficial due to their excellent antihypertensive properties with the added benefit of ameliorating hyperfiltration, which attends the reduction in renal mass from uninephrectomy. This hyperfiltration, is not driven by a rise of intraglomerular pressure (9). The Kidney Disease Improving Global Kidney Outcomes (KDIGO) Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Follow-up Care of Living Kidney Donors states: “There is a need for well-designed studies to quantify the impact of live kidney donation on hypertension risk, as well as the impact of hypertension before and after donation on clinical outcomes including lifetime ESRD incidence” (10).

The aims of this analysis are, therefore, to determine the incidence and risk factors for hypertension after donation, describe how it is treated and also assess its association with the development of reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), proteinuria, ESRD, cardiovascular disease (CVD) and death.

Materials and methods

Study population

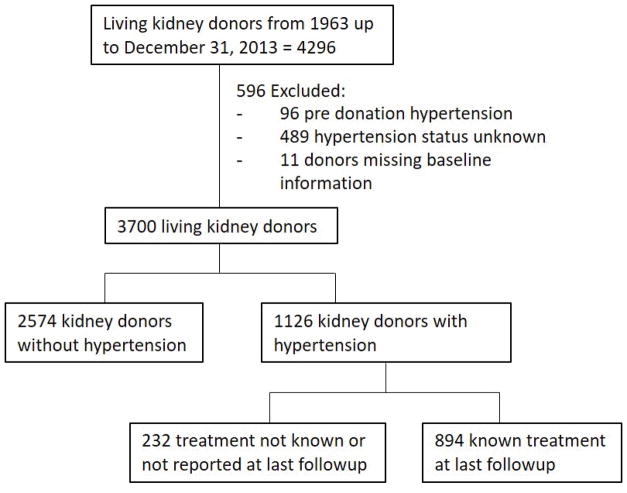

This is a longitudinal followup study of kidney donors who have donated between 1963 and December 31, 2014 (n=4296) at the University of Minnesota. Of these, 96 were excluded only from the incidence analysis because of pre-donation hypertension, 489 were also excluded because there were no records of their hypertension status (i.e. surveys not returned or missing answers on the surveys they returned) and 11 donors had missing information at time of donation (Figure 1). The remaining 3700 kidney donors in whom hypertension status was known, 1126 developed post-donation hypertension, and 894 of them reported being on treatment. The type and date of initiation of anti-hypertension medication was reported (Figure 1). We also studied the outcomes of the 96 donors who were hypertensive at time of donation. Donors were consented and all procedures were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (HSC #0301M39762).

Figure 1. Study participants.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria algorithm.

Data gathering methods

Laboratory and demographic variables are entered into our database at time of donation. Starting in 2003, donors are contacted at 6, 12 and 24 months, and then every 3 years indefinitely as previously described (11). Most donors, 87.5%, returned at least one survey. At each contact, donors are asked about hypertension requiring treatment. Donors are also asked to provide recent laboratory test results and copies of records (or, if not done, to have these tests); alternatively, with donors’ permission, we contact their local clinics for recent medical history, physical examination notes, and laboratory test results, including serum creatinine, glucose, urinalysis, and urinary protein measurements. Blood pressure measurements are performed at each patient clinic site following routine care procedures. Blood pressure measurements were reported at the time of evaluation and date of last follow-up. In addition, blood pressure measurements were obtained from clinical records and from patient surveys at varied time points and this data were used to assess the progression of blood pressure from time of donation to last followup.

Exposures and outcomes

Hypertension was defined by receipt of antihypertensive medications. Donors who had a diagnosis of hypertension (HTN) were asked to provide the date of initial diagnosis and provided the name and start date for each antihypertensive agents. Antihypertensive agents were grouped as follows: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) vs. other classes. Proteinuria was defined as a urinary albumin excretion > 30 mg/g creatinine, 24-hour urinary protein > 200 mg/day or ≥ 2+ on urine dipstick. End stage renal disease (ESRD) was defined by needing dialysis, undergoing a kidney transplant, or being placed on the deceased donor wait list for a transplant. To calculate serial eGFR, we used the CKD - EPI equation (12). Hyperlipidemia was defined in the survey as high cholesterol treated by diet or medication.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous data with normal distributions are presented as mean (SD) and categorical variables using frequencies and percentages. Differences between groups were assessed using student t-test and Chi-square for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The progression of blood pressure by time was determined using mixed models analysis for repeated measures with unequally spaced time points with an unstructured covariance structure. The estimated mean blood pressure values were plotted as a function of time since donation. A main effect by hypertension status and by time since donation were determined. An HTN status × time since donation interaction term was considered to determine if progression of blood pressure was different between groups. Cox proportional hazard model multivariate stepwise procedure was used to determine covariates associated with the development of hypertension. Variables entered in the model included: sex, age, race, relationship to recipient, family history of HTN and the following variables at time of donation (BMI, serum glucose, eGFR, SBP and DBP, hyperlipidemia and smoking status). A significance level of 0.15 and 0.20 was required to allow a variable for entry and stay into the model, respectively. Time of censoring was the date of last follow-up and death was modeled as a competing risk factor for incident hypertension and for all clinical outcomes. Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate HRs for incident hypertension by quintiles of age at time of donation adjusted for same variables as described above. Kaplan-Meir cumulative incident curves were developed by quintiles of age at time of donation and categories of risk factors. Difference among quintiles of age and categories of risk factors were assessed using Log-rank test. Risk factors for incident hypertension chosen were: male sex, age at time of donation > 49.6 years, family history of hypertension, BMI > 25 kg/m2, SBP and/or DBP >130/85 mmHg, and hyperlipidemia. Based on the number of risks factors, donors were placed in four different categories: no risk factors, 1, 2 or more than 3 risk factors. Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess unadjusted HRs for incident hypertension by categories of risk factors. We chose not to adjust in this case because the risk factor categories included the potential confounders. Cox proportional hazard models were also used to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for death, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, ESRD and development of eGFR <60, <45 and <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 in those with and without hypertension. HRs were adjusted for the same variables as described above and for the development of post-donation CVD, diabetes and proteinuria as time varying covariates. Cox proportional hazard models were also used to estimate, in those with post-donation hypertension, HRs for all clinical outcomes with death as a competing risk factor between those on ACEI or ARB (ACE/ARB) vs. those on other agents. HRs were adjusted for sex, race, current age, relationship to recipient time to diagnosis of hypertension and covariates present at time of last followup: body mass index, fasting glucose, SBP, DBP, hyperlipidemia, presence of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, smoking and eGFR. Because diagnosis of hypertension and time of initiation of anti-hypertensive treatment occurred at varying times during follow-up, hypertension and anti-hypertensive treatment were modeled as time varying covariates. Hypertension, diabetes and proteinuria were also modeled as a time varying covariates. A Cox proportional hazard model was also used to estimate HRs for clinical outcomes in those with hypertension at time of donation and those without baseline hypertension after adjustment for same variables as described for the multivariate stepwise procedure using death as a competing risk factor. Statistical significance was set at a p-value of 0.05. SAS version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, was used for all statistical analysis.

Results

Of the 4296 individuals who donated a kidney between 1963 – 2014, 96 were excluded from the incidence analysis for having pre-donation hypertension and 489 donors with unknown post-donation hypertension status (Figure 1). Donors with unknown hypertensive status were more likely to be women (54.8 vs. 31.5%), more likely to be smokers (45.7 vs. 29.2%) and had a lower eGFR at donation (99.7 vs. 103.4 mL/min/1.73m2), but were otherwise comparable to those with known hypertension status (data not shown). Of the remaining 3700, 1126 (30%) donors reported hypertension and 894/1126 (79.4%) reported receiving treatment and provided the anti-hypertensive agent(s) they were receiving (Figure 1). Donors who developed hypertension were on average 2 years older, were more likely to have donated to a first degree relative, have smoked and had a higher BMI, higher SBP, DBP, higher fasting glucose, and higher total cholesterol (Table 1). eGFR at donation was lower in those who later developed hypertension; mean (SD); 99.4 (33.8) vs. 105.1 (33.2), p < 0.001. In those with post-donation hypertension, SBP by 2.9 (0.2) mmHg/decade, progressing at a greater rate than in those without post-donation hypertension 2.0 (0.2) mmHg/decade, p < 0.0001 (Figure 2). DBP rose by 0.9 (0.1) mmHg/decade in those who developed post-donation hypertension compared to 2.4 (0.2) mmHg/decade, p < 0.0001 in those without post-donation hypertension.

Table 1.

General characteristics at time of donation, mean (SD) or %

| Post-donation Hypertension | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| No | Yes | ||

|

|

|||

| 2574 (69.6) | 1126 (30.4) | P-value | |

| Males, % | 41.0 | 42.7 | 0.3 |

| Age, years | 38.3 (11.4) | 40.4 (11.9) | < 0.001 |

| White | 95.1 | 94.4 | 0.4 |

| First degree relative, % | 67.8 | 85.1 | < 0.001 |

| Smoker, % | 26.5 | 36.0 | < 0.001 |

| Family history of HTN, % | 32.0 | 33.0 | 0.6 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.6 (4.3) | 26.3 (4.5) | < 0.001 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 105.1 (33.2) | 99.4 (33.8) | < 0.001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 118.8 (12.7) | 121.4 (13.2) | < 0.001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 72.1 (9.7) | 75.5 (9.8) | < 0.001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.89 (0.16) | 0.92 (0.17) | < 0.001 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 92.4 (12.8) | 95.7 (15.9) | < 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 190.7 (37.7) | 197 (41.5) | 0.002 |

HTN = hypertension. BMI = body mass index. eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate. SBP = systolic blood pressure. DBP = diastolic blood pressure.

Figure 2. Observed and predicted progression of post donation blood pressure in those with and without post-donation hypertension.

SBP = systolic blood pressure and DBP = diastolic blood pressure. Circles are observed values and lines are predicted values. The mean (SE) post donation SBP/DBP was greater in hypertensives donors 123.4 (0.4)/74.5 (0.3) mmHg than in non-hypertensives donors 120.7 (0.2)/73.6 (0.2) mmHg, p < 0.0001. The (mean (SE) SBP slope was greater for hypertensives donors than in non-hypertensive donors, p < 0.0001. The (mean (SE) slope for DBP was greater in non-hypertensives than in hypertensives, p < 0.0001.

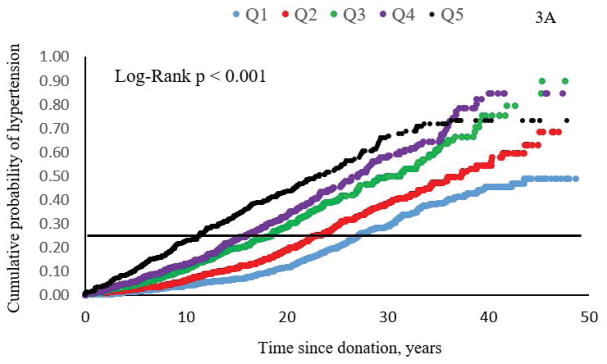

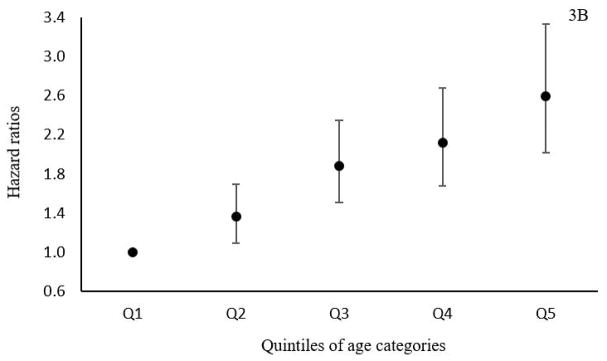

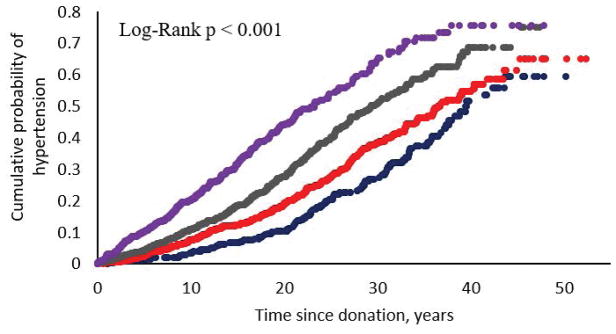

The median (IQ range) time to diagnosis of hypertension was 15.3 (range 7.9 – 23.7) years after donation and mean (SD) age at diagnosis was 56.7 (12.6) years. Figure 3A shows cumulative probability of hypertension by quintiles of age at time of donation. The number of years from donation to reach a 25% cumulative probability of hypertension for the group of individuals who at time of donation were in the lowest quintile of age was 29.8 years compared to 13.2 years for those who were in the highest quintile of age (> 49.6 years) at time of donation, Log-Rank test p < 0.001. Figure 3B shows the adjusted HRs for incident hypertension in kidney donors by quintiles of age at donation. Risk of hypertension development was 2.6 fold greater in those who donated in the highest quintile of age compared to those who donated in the lowest quintile of age. Cumulative probability of hypertension was also higher in donors who had a greater number of any of the following risk factors at time of donation: age ≥ 49.6 years, family history of hypertension, body mass index ≥ 25 kg/m2, SBP ≥ 130 mmHg, DBP ≥ 85 mmHg and hyperlipidemia. For those with no risk factors, the mean time to hypertension was 31.0 years (95% CI 28.1 – 34.1) years compared to 13.2 (95% CI 11.4 – 15.0) years for those with 3 or more risk factors, Log-Rank p < 0.001. Accordingly, the HR for developing hypertension progressively increased with more risk factors and in those with 3 or more risk factors the HR was 3 fold higher than for those with no risk factor at time of donation (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Cumulative probability of post donation hypertension by quintiles at age of donation (A) and adjusted hazard ratios for incident hypertension (B).

Q = quintiles of age at time of donation. Q1 = 15.5 – 27.8, Q2 = 27.9 – 35.1, Q3 = 35.2 – 42.0, Q4 = 42.1 – 49.5 and Q5 = 49.5 – 74.9 years. For graph B, values are HRs (95% CI).

Figure 4.

Cumulative incidence of post donation hypertension by number of risk factors at time of donation.

Predictors of hypertension development

Older age, family history of hypertension, higher BMI, higher fasting serum glucose, SBP, DBP, hyperlipidemia and being a smoker were associated with a higher risk of incident hypertension (Table 2). The strongest covariates associated with this risk were family history of hypertension, HR 1.25 (95% CI: 1.08 – 1.46) and hyperlipidemia 3.1 (95% CI 2.65 – 3.63). Being white was associated with a 30% lower risk of developing hypertension, p = 0.03. Donating to a first-degree family member was, however, not associated with incident hypertension (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable risk of incident hypertension (n = 3445)

| At donation | HRs (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 1.03 (1.03, 1.04) | < 0.001 |

| White | 0.7 (0.51, 0.97) | 0.03 |

| Family history of HTN | 1.25 (1.08, 1.46) | 0.004 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 1.05 (1.04, 1.07) | < 0.001 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.03 |

| SBP, mmHg | 1.02 (1.01, 1.02) | < 0.001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 0.005 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3.1 (2.65, 3.63) | < 0.001 |

| Smoker | 1.12 (0.97, 1.31) | 0.1 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.07 |

HRs = hazard ratios. HTN = hypertension. BMI = body mass index. eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate. SBP = systolic blood pressure and DBP = diastolic blood pressure. For continuous variables HR is per unit value. Variables entered in the model included: sex, age, race, relationship to recipient, family history of HTN and the following variables at time of donation (BMI, serum glucose, eGFR, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, hyperlipidemia and smoking status). A total of 3700 individuals were entered into the mode, but due to missing values only 3445 were used in the multiple regression procedure.

Antihypertensive use and adequacy of blood pressure control

Most (61.2%) of hypertensive donors are treated with one antihypertensive agent, 25.3% are treated with 2, while 13% required ≥ 3 agents, data not shown. The most commonly prescribed agents were ACE/ARB alone or combined with other agents, 38%. In 19.1% ACEI were used as the only treatment and 6% were treated with an ARB alone. The combination of a diuretic or a beta-blocker with ACE/ARB represented 10.8% and ACE/ARB with a calcium channel blocker or a vasodilator was used in 2.3% of hypertensive donors. At last follow-up, donors on ACE/ARB were highly comparable to donors treated with other agents except for having a lower pulse pressure and being 4 years older (Table 3).

Table 3.

Donor characteristics according to anti-hypertensive class at last followup.

| Categories of anti-hypertensive agents | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| ACEI or ARB | Other anti-hypertensive agents | p value | |

| n (%) | 340 (38) | 554 (62) | |

| Male, % | 45.0 | 40.4 | 0.2 |

| Age at HTN diagnosis | 56 (11.8) | 57.2 (12.6) | 0.2 |

| Current age | 71.2 (12.6) | 67.6 (11.9) | <0.001 |

| Time to HTN, years | 16.2 (10.2) | 16.1 (10.3) | 0.9 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 61.3 (21.1) | 58 (20.5) | 0.5 |

| SBP, mmHg | 128.4 (14.7) | 129.8 (16.6) | 0.2 |

| DBP, mmHg | 76.7 (9) | 75.3 (11.3) | 0.06 |

| Pulse pressure, mmHg | 51.7 (13) | 54.5 (15.6) | 0.006 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.8 (5.3) | 29.6 (5.9) | 0.6 |

Values are means (SD). HTN = hypertension. eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate. SBP and DBP = systolic and diastolic blood pressure. ESRD = end stage renal disease. CVD = cardiovascular disease. BMI = body mass index.

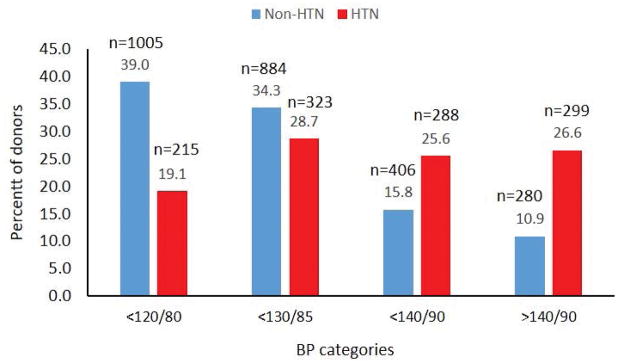

At last follow-up, 73.4% of hypertensive donors had BP < 140/90 mmHg and 19% had systolic and diastolic blood pressure values in the optimal range < 120/80 mmHg (Figure 5). In those without a diagnosis of hypertension, 280 (10.9 %) reported blood pressure values in the hypertensive range and 15.8% in the pre-hypertensive range.

Figure 5.

Level of blood pressure control by hypertension status.

Hypertension and risk of major events

After accounting for covariates present at time of donation and post-donation conditions including diabetes, hyperlipidemia and new cardiovascular disease, we found that hypertensive donors were more likely to have diabetes, HR 1.77 (95% CI 1.2–2.6), p=0.004 and more likely to have proteinuria, HR 1.55 (95% CI 1.03–2.32), p=0.03 (Table 4). A sensitivity analysis excluding donors who developed post-donation diabetes continued to show an increase in HR for proteinuria for those who developed post-donation hypertension, HR 1.84 (95% CI 1.15–2.90), p=0.01. Hypertensive donors were more likely to have eGFR <60, <45 and <30 mL/min/1.73m2 (Table 4). The risk of developing ESRD, however, was not higher in those with hypertension: HR 0.96 (95% CI 0.15 – 8.23), p = 1.0. Similarly, the risk of death was not different between those with and without hypertension, (Table 4).

Table 4.

Clinical characteristics of those with post-donation hypertension at last followup

| Outcomes | Non-HTN | HTN | Hazard ratios (95% CI) | p Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | 3.8 (99/2579) | 11.7 (131/1121) | 1.03 (0.46 – 2.40) | 0.9 |

| Diabetes | 2.1 (53/2579) | 15.8 (177/1121) | 1.77 (1.20 – 2.61) | 0.004 |

| Proteinuria | 3.2 (83/2576) | 14.6 (163/1118) | 1.55 (1.03 – 2.32) | 0.03 |

| eGFR < 60 | 32.2 (831/2579) | 56.6 (634/1121) | 1.44 (1.21 – 1.72) | <0.0001 |

| eGFR < 45 | 6.6 (170/2579) | 24.9 (279/1121) | 1.89 (1.42 – 2.52) | <0.0001 |

| eGFR < 30 | 0.89 (23/2579) | 7.1 (80/1121) | 2.26 (1.24 – 4.25) | 0.009 |

| ESRD | 0.16 (4/2579) | 2.1 (23/1118) | 0.96 (0.15 – 8.23) | 0.97 |

| CVD | 4.4 (113/2572) | 25.8 (288/1117) | 1.42 (1.05 – 1.92) | 0.02 |

HRs adjusted for age, race, relationship category and at time of donation (fasting glucose, body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, smoking and estimated glomerular filtration rate, diabetes post-donation (except when diabetes was the dependent variable), hyperlipidemia, and cardiovascular disease (except when CVD was the dependent variable). Hypertension, diabetes and proteinuria were modeled as a time varying covariate for death, proteinuria, ESRD and eGFR <60, <45 and <30. In the case of CVD only hypertension and diabetes were modelled as time varying covariates. For diabetes, only hypertension was modelled as a time varying covariate. ESRD = end stage renal disease. CVD = cardiovascular disease. All events occurred after diagnosis of hypertension.

Anti-hypertensive agents and outcomes

Hypertensive donors on ACE/ARB when compared to use of other agents, had a lower risk of eGFR <45; HR 0.64 (95% CI 0.45, 0.90), p = 0.01 and lower risk of ESRD: 0.03 (95% CI 0.001, 0.21), p = 0.004 (Table 5). ACEI or ARB use was not associated with proteinuria development, 1.04 (95% CI 0.63, 1.68), p value = 0.9 or death from any cause 1.25 (95% CI 0.67, 2.27), p value = 0.5 (Table 5). An additional analysis comparing non-hypertensive donors, hypertensive donors treated with ACEI/ARB and hypertensive donors treated with other agents, showed that post-donation hypertension was associated with a greater HRs for all clinical outcomes, except for eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73m2, regardless of the type of treatment received. The risk of eGFR<30 mL/min/1.73m2 or ESRD in those treated with ACE/ARB were not different from those observed in donors who did not develop post-donation hypertension, (Table 6).

Table 5.

Impact of ACEI/ARB use and clinical outcomes.

| Anti-hypertensive Category | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| ACEI/ARB | Other | |||

|

| ||||

| Clinical outcome n (%) | 340 (38) | 554 (62) | HRs (95% CI) | p value |

| Death | 23 (6.8) | 64 (11.5) | 1.25 (0.67, 2.27) | 0.5 |

| CVD, n (%) | 41 (12.3) | 94 (17.3) | 0.8 (0.52, 1.22) | 0.3 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 27 (8.1) | 56 (10.2) | 0.96 (0.57, 1.58) | 0.4 |

| Proteinuria, n % | 32 (9.61) | 58 (10.6) | 1.04 (0.63, 1.68) | 0.9 |

| eGFR<60, n (%) | 123 (36.3) | 237 (42.6) | 0.88 (0.69, 1.11) | 0.3 |

| eGFR<45, n (%) | 53 (15.6) | 136 (24.3) | 0.64 (0.45, 0.9) | 0.01 |

| ESRD, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 15 (2.7) | 0.03 (0.001, 0.21) | 0.004 |

HRs adjusted for sex, race and the following variables at time of last followup (age, fasting glucose, body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, smoking and estimated glomerular filtration rate, diabetes post-donation (except when diabetes was the dependent variable), hyperlipidemia, and cardiovascular disease (except when CVD was the dependent variable). Hypertension, diabetes and proteinuria were modeled as a time varying covariate. ESRD = end stage renal disease. CVD = cardiovascular disease. All events occurred after diagnosis of hypertension. Use of ACE inhibitors (ACEI) or ARB and diabetes were included as a time varying covariate.

Table 6.

HRs for clinical outcomes by hypertension status and anti-HTN treatment.

| HRs (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Clinical outcome | Non-HTN (1) | HTN other meds (2) | HTN ACE/ARB (3) | p value, 2 vs 1 | p value, 3 vs 1 |

| Diabetes | 1 | 2.75 (1.90, 3.98) | 2.70 (1.77, 4.08) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| CVD | 1 | 2.05 (1.60, 2.62) | 1.74 (1.27, 2.35) | < 0.0001 | 0.0004 |

| Proteinuria | 1 | 2.40 (1.74, 3.29) | 2.59 (1.80, 3.70) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| eGFR 60 | 1 | 1.12 (0.97, 1.28) | 1.14 (0.96, 1.35) | 0.12 | 0.13 |

| eGFR45 | 1 | 1.96 (1.57, 2.45) | 1.61 (1.20, 2.13) | < 0.0001 | 0.001 |

| eGFR30 | 1 | 3.73 (2.33, 6.08) | 1.83 (0.92, 3.47) | < 0.0001 | 0.07 |

| ESRD | 1 | 4.99 (1.82, 15.1) | 0.81 (0.11, 3.72) | 0.002 | 0.07 |

| Death | 1 | 2.71 (1.82, 3.98) | 2.30 (1.29, 3.86) | 0.0005 | 0.0005 |

HRs adjusted for sex, age, race, relationship to recipient, family history of HTN and the following variables at time of donation: serum glucose, eGFR, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, presence of hyperlipidemia and smoking status. Time of initiation of ACEinh/ARB or other medications were treated as a time varying covariates.

Outcomes in donors who were hypertensive at donation

Donors with hypertension prior to donation (n=96) were more likely to have family history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia. They were about 10 years older, had greater BMI, SBP, DBP and higher serum glucose values than those without hypertension at time of donation (Table 7). Donors with pre-donation hypertension were diagnosed with HTN 4.3 (1.9) years before donation. Risks for the different clinical outcomes between those with and without hypertension at time of donation were not different (Table 8).

Table 7.

General characteristics in donors with and without hypertension at donation; mean (SD) or %

| n | HTN at baseline | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| No | Yes | ||

|

| |||

| 4200 | 96 | p value | |

| Females | 56.8 | 56.3 | 0.9 |

| Age, years | 38.9 (11.6) | 49.9 (10.7) | < 0.0001 |

| White | 94.2 | 96.9 | 0.3 |

| First degree relative | 74.1 | 68.8 | 0.2 |

| Smoker | 31.2 | 22.9 | 0.08 |

| Family history of HTN, | 31.8 | 47.7 | 0.002 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 4.9 | 25.0 | < 0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.8 (4.3) | 27.4 (3.8) | 0.0006 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 103.0 (33.9) | 98.0 (35.3) | 0.2 |

| SBP, mmHg | 119.6 (13) | 130.2 (12.8) | < 0.0001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 73.3 (9.9) | 78.7 (10) | < 0.0001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.90 (0.16) | 0.89 (0.18) | 0.4 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 93.2 (14.5) | 99.6 (16.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 192.0 (39.1) | 200.6 (37.6) | 0.1 |

HTN = hypertension. BMI = body mass index. eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate. SBP = systolic blood pressure. DBP = diastolic blood pressure.

Table 8.

Prevalence and adjusted HRs for clinical outcomes in donors with (n=96) and without hypertension at donation.

| Outcomes | Non-HTN, % (n/N) | HTN, % (n/N) | HRs (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | 6.2 (230/3700) | 8.3 (8/96) | 0.83 (0.20, 2.31) | 0.8 |

| Proteinuria | 6.7 (246/3694) | 11.5 (11/96) | 1.42 (0.42, 3.49) | 0.5 |

| eGFR < 60 | 39.59 (1465/3700) | 58.33 (56/96) | 1.12 (0.73, 1.63) | 0.6 |

| eGFR < 45 | 12.14 (449/3700) | 20.83 (20/96) | 0.98 (0.46, 1.84) | 1.0 |

| eGFR < 30 | 2.78 (103/3700) | 6.25 (6/96) | 1.89 (0.53, 5.22) | 0.3 |

| ESRD | 0.73 (27/3697) | 1.05 (1/95) | - | |

| CVD | 10.87 (401/3689) | 19.15 (18/94) | 0.89 (0.39, 1.75) | 0.8 |

| Death | 6.2 (230/3700) | 8.3 (8/96) | 0.76 (0.18, 2.18) | 0.7 |

HRs adjusted for: age, sex, race, relationship, family history, BMI, glucose, SBP, DBP, eGFR, smoke and hyperlipidemia. HRs for ESRD could not be calculated. eGFR < 60, 45, 30 = estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60, 45, 30.

Discussion

These results demonstrate that roughly a third of kidney donors develop hypertension after donation and risk factors for its development are similar to what is seen in the general population. We found that one fourth of donors receiving anti-hypertensive medications are poorly controlled (>140/90 mmHg) and one tenth of donors without a diagnosis of hypertension had blood pressure readings in the hypertensive range.

We have previously shown that the prevalence of hypertension is similar to general population controls drawn from the 2003–2004 and 2005–2006 waves of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) after matching on age, gender, race and BMI(11). The prevalence of hypertension in our current cohort compared to US adults from a more recent wave of NHANES 2011 – 2014 is shown in Table 9. The prevalence in US adults is twofold higher in those <60 years of age and 1.7 fold higher in those >60 years of age when compared to our cohort of mostly white kidney donors. Prevalence of hypertension, however, in non-white kidney donors does appear to be higher. Lentine et al., using medical claims and drug treated hypertension definitions, demonstrated a 30–50% higher prevalence of hypertension in non-Hispanic black donors compared to non-Hispanic white donors, but no difference between non-Hispanic black donors and NHANES controls of the same ethnicity (13). Hispanic donors, however, had a higher prevalence than the general population Hispanic controls. Collectively, these studies do not suggest that prevalence of hypertension is higher in donors with the exception of Hispanic donors. Our data cannot shed light on hypertension in minorities as most of our donors are white.

Table 9.

Prevalence of hypertension by categories of age at time of last follow-up in donors compared to U.S. population.

| Age categories, years | Donors | NHANES 2011 – 2014 |

|---|---|---|

| 18 – 39 | 4.2% | 7.3% |

| 40 – 59 | 15.6% | 32.4% |

| > 59 | 47.7% | 65.0% |

Comparing incidence of hypertension in donors and appropriate controls has been difficult because most donors are not followed prospectively. In addition, most data regarding incident hypertension in the general population comes from cohorts like the Framingham Study (14), Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study (15) and others in which the ascertainment of incident hypertension has been carried out for the near term only. For example, the incidence of hypertension in 5554 ARIC participants followed for a median of 11.9 years was 21.6%. The mean age of these participants was 61.9 years. The older age (compared to kidney donors) and the observation that minimal hypertension is seen in the first 10 years after donation limits the ability to make any meaningful comparisons regarding incident hypertension in kidney donors. Perhaps the most comprehensive and careful attempt to answer whether the incidence of hypertension is higher in kidney donors comes from the meta-analysis by Boudville et al. (4). In 6 studies involving 249 donors and 161 controls, only one study reported a higher incidence in donors (16). Of note, a recent meta-analysis of 52 studies comparing 118426 kidney donors to 117656 controls suggest no evidence of higher all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease or hypertension in donors (17). Standardized mean difference of DBP (mean difference in DBP between donors and controls divided by pooled standard deviation) was 0.17 mmHg higher in donors. We noted a greater rise in DBP in donors without post-donation hypertension (compared to hypertensive donors). Nevertheless, higher risk of incident cardiovascular disease was mainly in those who developed post-donation hypertension. A plausible explanation for this apparently paradoxical association is that SBP and pulse pressure are better predictor of cardiovascular diseases than DBP or mean blood pressure (18–21). In addition, those with post-donation hypertension were more likely to be diabetics, which is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (22, 23). The rates of CVD we observed in nonhypertensive donors of 4.5% and 15.3% in hypertensive donors are considerably lower than the rate of 36% reported in non-Hispanic whites (24).

The covariates that we found to be associated with incident hypertension (age, gender, family history of hypertension, SBP, DBD and BMI) carried almost similar weights as they do in the general population. For example, family history of hypertension was associated with a 25% higher risk in our cohort and in the Framingham cohort it was associated with 20% risk. BMI, SBP, DBP at time of donation conveyed almost identical risks in donors and Framingham participants (14). This may indirectly suggest that there might be no effect modification between uninephrectomy and other risk factors for the development of hypertension.

The majority of kidney donors had blood pressure value <140/90 mmHg while receiving treatment. Data from the 2009–2010 NHANES wave indicate that only 45.5% of the general population have adequately controlled blood pressure (25). However, 25% have poorly controlled blood pressure and 1 out of 10 donors with repeated readings >140/90 mmHg was not receiving treatment. Donors deserve to have a long-term plan for medical care so conditions that are readily treatable such as hypertension and diabetes do not go unaddressed.

These results suggest that hypertension is associated with reduced eGFR and proteinuria. This association is far from causal as the link between non-malignant hypertension and CKD is weak. In fact, a meta-analysis of 10 randomized trials of 26521 patients assigned to antihypertensive therapy or a lower blood pressure target failed to show benefit in terms of reducing renal endpoints that spanned rises in creatinine, BUN or ESRD (8). Therefore, in the general population and also in kidney donors, it remains unclear whether pre-existent renal disease is sufficient to explain the association of hypertension and future loss of renal function.

A third of donors received ACE/ARB. We expected to see more frequent use of these agents considering their ability to abrogate intra-glomerular hypertension and reducing the likelihood of native proteinuric kidney disease progression (26, 27). Although currently unknown, it is conceivable that the general practitioner would be reluctant to use these agents in someone with a single kidney. The use of these agents in our cohort was associated with less donors reaching an eGFR < 45 mL/min/1.73m2 or ESRD as compared to those treated with other agents and the risk was similar to non-hypertensive donors. While this data, by no means, provides conclusive evidence of the superiority of ACEI/ARB in this population, the observed associations provide a rationale for performing further research to determine the utility of ACEI/ARB use to decrease the risk of low GFR and the development of ESRD in individuals with post-donation hypertension. Importantly, the mechanism of hyperfiltration after donation is not driven by a rise in intra-glomerular pressure, but rather by an increase in the glomerular surface area (9), therefore, such an observed benefit cannot be readily explained by these agents ability to alleviate intra-glomerular hypertension. In reality, only a large size, randomized clinical trial can provide evidence supporting the associations observed in this retrospective analysis. One has to also consider that the demonstrated benefit of these ACEI/ARB are largely seen in patients with proteinuria and extrapolating that information to kidney donors who are generally non-proteinuric is not without limitations. Nevertheless, we feel that ACEI and ARB should be considered amongst the preferred agents in kidney donors who are hypertensive.

These analyses have limitations. The overwhelming majority of our donors are Caucasian (97% vs. 75% in US kidney donors), which limits extrapolating the results from this analysis into other ethnic groups. The issue of self-report is also important. However, previous studies have shown that the concordance between hypertension diagnoses was extremely high when it was defined by need for treatment (28, 29). Moreover, the majority of diagnosis was abstracted from medical records, as well. The associations we observed between ACEI/ARB and less eGFR <45 ml/min/1.73m2 or and ESRD is greatly limited by the retrospective design of the study and possible selection bias.

In all, this analysis shows that kidney donors have similar risk factors for developing hypertension to the general population. ACEI or an ARB are the most commonly used antihypertensive medications and their use appears to be associated with lower risks of eGFR< 45 ml/min/1.73m2 ESRD. The latter can only be confirmed in a prospectively designed study involving a much larger number of donors. Opportunities exist to optimize level of blood pressure control in hypertensive donors and actively follow donors so hypertension does not go untreated.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (5P01 DK013083).

Abbreviations

- ACEI

ACE inhibitor

- ACEI

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor

- ARB

angiotensin receptor blocker

- ARB

angiotensin receptor blocker

- ARIC

Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DBP

diastolic blood pressure

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- HR

hazard ratio

- HTN

hypertension

- KDIGO

Kidney Disease Improving Global Kidney Outcomes

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

References

- 1.Brenner BM, Garcia DL, Anderson S. Glomeruli and blood pressure. Less of one, more the other? Am J Hypertens. 1988;1(4 Pt 1):335–347. doi: 10.1093/ajh/1.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanzaki G, Tsuboi N, Haruhara K, Koike K, Ogura M, Shimizu A, et al. Factors associated with a vicious cycle involving a low nephron number, hypertension and chronic kidney disease. Hypertens Res. 2015;38(10):633–641. doi: 10.1038/hr.2015.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasiske BL, Ma JZ, Louis TA, Swan SK. Long-term effects of reduced renal mass in humans. Kidney Int. 1995;48(3):814–819. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boudville N, Prasad GV, Knoll G, Muirhead N, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Yang RC, et al. Meta-analysis: risk for hypertension in living kidney donors. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(3):185–196. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-3-200608010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anjum S, Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Bae S, Luo X, Grams ME, et al. Patterns of End-Stage Renal Disease Caused by Diabetes, Hypertension, and Glomerulonephritis in Live Kidney Donors. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(12):3540–3547. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matas AJ, Hays RE, Ibrahim HN. A Case-Based Analysis of Whether Living Related Donors Listed for Transplant Share ESRD Causes with Their Recipients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(4):663–668. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11421116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlessinger S, Tankersley M, Curtis J. Clinical documentation of end stage renal disease due to hypertension. Am J Kid Dis. 1994;25(5):655–660. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)70275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu C. Does non-malignant hypertension reduce the incidence of renal dysfunction? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hum Hypertens. 2001;15:99–106. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lenihan CR, Busque S, Derby G, Blouch K, Myers BD, Tan JC. Longitudinal study of living kidney donor glomerular dynamics after nephrectomy. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(3):1311–1318. doi: 10.1172/JCI78885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.OUTCOMES KDIG. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Follow-up Care of Living Kidney Donors. 2017 doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001769. Available from: http://kdigo.org/home/guidelines/livingdonor/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Ibrahim HN, Foley R, Tan L, Rogers T, Bailey RF, Guo H, et al. Long-term consequences of kidney donation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(5):459–469. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, Saab G, Salvalaggio PR, Axelrod D, et al. Racial variation in medical outcomes among living kidney donors. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):724–732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dannenberg AL, Garrison RJ, Kannel WB. Incidence of hypertension in the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health. 1988;78(6):676–679. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.6.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juraschek SP, Bower JK, Selvin E, Subash Shantha GP, Hoogeveen RC, Ballantyne CM, et al. Plasma lactate and incident hypertension in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(2):216–224. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watnick TJ, Jenkins RR, Rackoff P, Baumgarten A, Bia MJ. Microalbuminuria and hypertension in long-term renal donors. Transplantation. 1988;45(1):59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Keefe L, Raymond A, Oliver-Williams C, et al. Mid and long term health risks in living kidney donors. Ann Intern Med. 2018 doi: 10.7326/M17-1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franklin SS, Wong ND. Hypertension and cardiovascular disease: contributions of the Framingham heart study. Global heart. 2013;8(1):49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sesso HD, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Hennekens CH, Gaziano JM, Manson JE, et al. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, pulse pressure, and mean arterial pressure as predictors of cardiovascular disease risk in Men. Hypertension. 2000;36(5):801–807. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.5.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Psaty BM, Arnold AM, Olson J, Saad MF, Shea S, Post W, et al. Association between levels of blood pressure and measures of subclinical disease multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19(11):1110–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bundy JD, Li C, Stuchlik P, Bu X, Kelly TN, Mills KT, et al. Systolic Blood Pressure Reduction and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Network meta-analysis. JAMA cardiology. 2017;2(7):775–781. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diabetes mellitus: a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease. A joint editorial statement by the American Diabetes Association; The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; The Juvenile Diabetes Foundation International; The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; and The American Heart Association. Circulation. 1999;100(10):1132–1133. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin-Timon I, Sevillano-Collantes C, Segura-Galindo A, Del Canizo-Gomez FJ. Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: Have all risk factors the same strength? World journal of diabetes. 2014;5(4):444–470. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i4.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update. Circulation. 2017:135. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo F, He D, Zhang W, Walton RG. Trends in prevalence, awareness, management, and control of hypertension among United States adults, 1999 to 2010. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(7):599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jafar TH, Schmid CH, Landa M, Giatras I, Toto R, Remuzzi G, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and progression of nondiabetic renal disease. A meta-analysis of patient-level data. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(2):73–87. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-2-200107170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruggenenti P. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II antagonism in nondiabetic chronic nephropathies. Semin Nephrol. 2004;24(2):158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skinner KM, Miller DR, Lincoln E, Lee A, Kazis LE. Concordance between respondent self-reports and medical records for chronic conditions: experience from the Veterans Health Study. The Journal of ambulatory care management. 2005;28(2):102–110. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200504000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tisnado DM, Adams JL, Liu H, Damberg CL, Chen WP, Hu FA, et al. What is the concordance between the medical record and patient self-report as data sources for ambulatory care? Med Care. 2006;44(2):132–140. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000196952.15921.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]