Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Levels of amyloid-β 42 (Aβ42), total Tau (tTau) and phosphorylated Tau-181 (pTau) are well-established cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers of Alzheimer disease (AD), but variability in manual plate-based assays has limited their use. We examined the relationship between CSF biomarkers, as measured by a novel automated immunoassay platform, and amyloid PET.

METHODS

CSF samples from 200 individuals underwent separate analysis for Aβ42, tTau and pTau with the automated Roche Elecsys cobas e 601 analyzer. Aβ40 was measured with the IBL plate-based assay. Positron emission tomography (PET) with Pittsburgh Compound B (PIB) was performed less than one year from CSF collection.

RESULTS

Ratios of CSF biomarkers (tTau/Aβ42, pTau/Aβ42 and Aβ42/Aβ40) best discriminated PIB-positive from PIB-negative individuals.

DISCUSSION

CSF biomarkers and amyloid PET reflect different aspects of AD brain pathology and therefore less than perfect correspondence is expected. Automated assays are likely to increase the utility of CSF biomarkers.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, biomarker, cerebrospinal fluid, cut-off, amyloid

1. Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD) refers to the progressive brain disease that is characterized by amyloid plaques, which are comprised primarily of amyloid-β peptide 42 (Aβ42), and neurofibrillary tangles, which are comprised primarily of Tau, including phosphorylated forms of Tau. Individuals with AD are typically asymptomatic (have no apparent cognitive decline) for one to two decades during the preclinical phase of the disease [1, 2]. As the disease progresses, individuals enter the symptomatic phase when they develop cognitive decline that culminates in dementia. Fluid biomarkers can identify individuals with AD brain pathology who are in either the preclinical phase or the symptomatic phase of the disease. Decreases in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ42 levels and increases in CSF total Tau (tTau) and phosphorylated Tau-181 (pTau) may be the earliest markers of AD brain pathology [3–6]. CSF Aβ42, tTau or pTau individually, and especially the ratios of CSF tTau/Aβ42 and pTau/Aβ42, predict future cognitive decline of cognitively normal adults [7, 8] and individuals diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to AD [9–12].

It is likely that the use of AD biomarkers will continue to increase in clinical practice and clinical trials. As demonstrated by clinicopathological series, the clinical diagnosis of AD can be incorrect [13], so biomarkers may be helpful in establishing an accurate diagnosis. CSF biomarkers are especially useful when the etiology of cognitive impairment is uncertain and AD is a possible cause [14]. Drug trials now routinely test CSF or imaging biomarkers in potential participants after it was found that many individuals enrolled in past AD drug trials did not have AD brain pathology [15–18]. CSF biomarkers are also being utilized in clinical trials to verify that drugs are having expected biological effects and may eventually be used as surrogate endpoints [15, 16]. When an effective drug for AD is available, CSF biomarkers will become even more important in guiding the diagnosis and management of patients.

CSF Aβ42, tTau and pTau were the first biomarkers described for AD [19] and now molecular imaging biomarkers have also become well established [20, 21]. Radiotracers that bind to β-amyloid (e.g., Pittsburgh Compund B [PIB], florbetapir, florbetaben, and flutametamol) or aggregated Tau (e.g., flortaucipir) can visualize plaques and tangles, respectively, with Positron Emission Tomography (PET). While these PET imaging techniques provide information regarding the degree and spatial distribution of brain pathology, there are limitations to their use, including high cost, limited access, use of radiation, and imaging of only a single type of pathology per scan [22, 23]. A number of studies have previously evaluated the relationship between CSF biomarkers of AD and amyloid PET and found a strong inverse correlation between levels of CSF Aβ42 and binding of amyloid PET tracers [3, 5, 6, 24–33]. The ratio of Aβ42 with another AD biomarker (e.g. tTau/Aβ42, pTau/Aβ42, or Aβ42/Aβ40) may provide the best correlation with amyloid PET measures [24, 30, 32].

The use of CSF biomarkers has been limited by a number of technical factors. There has been substantial variability in the intra- and inter-lab performance of the three most commonly used commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) for CSF Aβ42, tTau and pTau: INNOTEST, AlzBio3, and Meso Scale Discovery (MSD). Issues with these assays include high lot-to-lot variability [34] and between-lab variability associated with differences in lab procedures and analytical techniques since the assays are run manually [12, 35–37]. Practically, since most assays are based on the 96-well plate immunoassay format, labs must await a large number of samples to financially justify analysis, which in turn leads to delays in obtaining results. The lack of standardized reference materials for quantitation of these analytes has made it difficult to compare absolute values across assays and studies [38]. Taken together, these issues have prevented the establishment of universal diagnostic cut-offs for CSF biomarkers and decreased the potential utility of CSF biomarkers in the clinic and in clinical trials.

Next generation automated assay platforms are being developed to overcome the shortcomings of previous assay systems. One such assay platform is the Elecsys® cobas e 601analyzer developed by Roche Diagnostics. This assay platform exhibits high degrees of precision, accuracy, reliability and reproducibility, with very low variability, in large part due to its automation [39]. We tested this novel assay platform using CSF samples obtained from individuals who had also undergone amyloid PET. CSF Aβ42, tTau, and pTau were measured separately with Elecsys assays. CSF Aβ40 was measured with a standard plate-based ELISA [24]. We then examined the relationship between cortical amyloid load as defined by PIB PET and CSF Aβ42, Aβ40, tTau, pTau and three ratios of Aβ42 with another AD biomarker (tTau/Aβ42, pTau/Aβ42 and Aβ42/Aβ40).

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Participants, standard protocol approvals and consents

Participants were community-dwelling volunteers enrolled in studies of normal aging and dementia at the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) at Washington University in St. Louis. Participants had no neurological, psychiatric or systemic medical illness that might compromise longitudinal study participation and no medical contraindication to lumbar puncture (LP) or PET. All participants underwent clinical assessments that included the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR)[40]. APOE genotype was obtained from the Knight ADRC Genetics Core [41]. All procedures were approved by the Washington University Human Research Protection Office, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Participants included in this study underwent a clinical assessment, LP and PIB PET within a 365 day period. Of participants who met these criteria, two-hundred were selected based on cortical amyloid load by PIB PET (25% PIB-positive and 75% PIB-negative based on a previously established cut-off [42]). We chose to include more PiB-negative participant samples to enrich for discordant (PIB-negative and CSF biomarker positive) cases. Further, we chose participants with a broad range of CSF Aβ42 values. Selection was independent of participant demographics and clinical status.

2.2 CSF collection, processing and analysis

CSF was collected under standardized operating procedures. Participants underwent LP at 8 am following overnight fasting. Twenty to thirty mls of CSF was collected in a 50 ml polypropylene tube via gravity drip using an atraumatic Sprotte 20 gauge spinal needle. The entire sample was gently inverted to disrupt potential gradient effects and centrifuged at low speed to pellet any cellular debris. 500 uL of CSF was aliquoted into polypropylene tubes and stored at −80°C as previously described [5].

Aβ42, tTau, and pTau were measured with the corresponding Elecsys immunoassays on the Elecsys cobas e 601analyzer – a fully automated system. The Elecsys immunoassays are electrochemiluminescence immunoassays employing a quantitative sandwich principle with a total assay duration of 18 minutes. Pristine aliquots from the selected cohort were measured according to the Roche study protocol (RD002967) written specifically to measure these samples. Aβ40 concentrations were measured with a plate-based ELISA from IBL International (Hamburg, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A single lot of assays for each analyte (either Elecsys for Aβ42, tTau and pTau or IBL for Aβ40) was used to measure all samples to avoid lot-to-lot variability.

2.3 Amyloid Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging

Participants underwent a 60-minute dynamic scan with 11[C] Pittsburgh Compound B (PIB) [43]. PET imaging was performed with a Siemens 962 HR+ ECAT PET or Biograph 40 scanner (Siemens/CTI, Knoxville KY). Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using MPRAGE T1-weighted images was also acquired. Structural MRIs were processed using FreeSurfer [44] (http://freesurfer.net/) to derive cortical and subcortical regions of interest used in the PET processing [45, 46]. Regional PIB values were converted to standardized uptake value ratios (SUVRs) using cerebellar grey as a reference and partial volume corrected using a regional spread function approach [45, 46]. Values from the left and right lateral orbitofrontal, medial orbitofrontal, precuneus, rostral middle frontal, superior frontal, superior temporal, and middle temporal cortices were averaged together to represent a mean cortical SUVR. PIB positivity was defined as a mean cortical SUVR>1.42 [42], which is commensurate with a mean cortical binding potential of 0.18 that have previously been used to define PIB positivity [45].

2.4 Statistical analyses

Characteristics of PIB-positive and PIB-negative groups were compared using T-tests for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. Performance of the Elecsys assay has not yet been formally established for measuring Aβ42 concentrations <200 pg/ml or >1,700 pg/ml. None of the samples used for this study had Aβ42 concentrations <200 pg/ml. Concentrations of Aβ42 >1,700 pg/ml were extrapolated based on the calibration curve. These values are restricted to research use and are not for clinical decision making. Values for CSF biomarkers, including single analytes and ratios, were compared to PIB PET SUVR using Spearman correlation.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were performed to determine the cut-offs for each CSF biomarker analyte and ratio that best distinguished PIB-positive from PIB-negative individuals. Positive percent agreement (PPA) was defined as the percent of PIB-positive individuals who were positive by a CSF biomarker measure. Negative percent agreement (NPA) was defined as the percent of PIB-negative individuals who were negative by a CSF biomarker measure. Overall percent agreement (OPA) was defined as the sum of the PIB-positive individuals who were positive by a CSF biomarker measure and the PIB-negative individuals who were negative by a CSF biomarker measure divided by the entire cohort size. The CSF biomarker single analyte or ratio value with the highest Youden index (PPA plus NPA minus 1) was selected as the cut-off value. Analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism version 6.07 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

CSF samples from 198 individuals were analyzed (see Table 1 for participant characteristics). Samples from two participants in the selected cohort were omitted due to failure of PIB PET quality control (i.e., movement artifact or out of LP-PET window of 365 days). The average absolute interval from LP to PIB PET was 67 ± 78 days (mean ± standard deviation). Most of the participants (n=176, 89%) were cognitively normal at the time of CSF collection with a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) of 0, but some (n=22, 11%) had very mild (CDR 0.5) or mild (CDR 1) dementia. By design, 50 (~25%) of the individuals were PIB-positive (mean cortical SUVR>1.42). As expected, individuals who were PIB-positive were more likely to be cognitively impaired (30% versus 5%, p<0.0001), older (72.5 ± 7.2 versus 64.2 ± 9.6 years, p<0.0001), and carry an APOE ε4 allele (56% versus 31%, p<0.01). Additionally, PIB-positive individuals were more likely to be male (p<0.01) in this cohort.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| PIB negative | PIB positive | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n= | 148 | 50 | |

| CDR 0/0.5/1/2/3 | 141/7/0/0/0 | 35/11/3/1/0 | |

| CDR>0 (%), a | 5% | 30% | p<0.0001 |

| MMSE, b | 29.1 ± 1.2 | 28.0 ± 3.0 | p<0.001 |

| Age at LP (years), b | 64.2 ± 9.6 | 72.5 ± 7.2 | p<0.0001 |

| Gender (% male), a | 34% | 58% | p<0.01 |

| Education (years), b | 15.9 ± 2.5 | 15.5 ± 3.0 | N.S. |

| APOE ε4 positive (%), a | 31% | 56% | p<0.01 |

| PIB Mean cortical SUVR, b | 1.04 ± 0.12 | 2.40 ± 0.70 | p<0.0001 |

| Elecsys Aβ42, pg/ml, b | 1428 ± 610 | 789 ± 256 | p<0.0001 |

| IBL Aβ40, pg/ml, b | 13950 ± 4347 | 15310 ± 4147 | p=0.06 |

| Elecsys tTau, pg/ml, b | 191 ± 76 | 309 ± 127 | p<0.0001 |

| Elecsys pTau, pg/ml, b | 16.7 ± 7.8 | 30.3 ± 14.8 | p<0.0001 |

| Elecsys tTau/Aβ42, b | 0.150 ± 0.090 | 0.420 ± 0.173 | p<0.0001 |

| Elecsys pTau/Aβ42, b | 0.013 ± 0.010 | 0.041 ± 0.020 | p<0.0001 |

| Elecsys Aβ42/IBL Aβ40, b | 0.103 ± 0.028 | 0.052 ± 0.014 | p<0.0001 |

percent, p values by chi-square;

mean ± standard deviation, p values by student’s T-test

3.2. Correlations between CSF biomarker measures and PIB binding

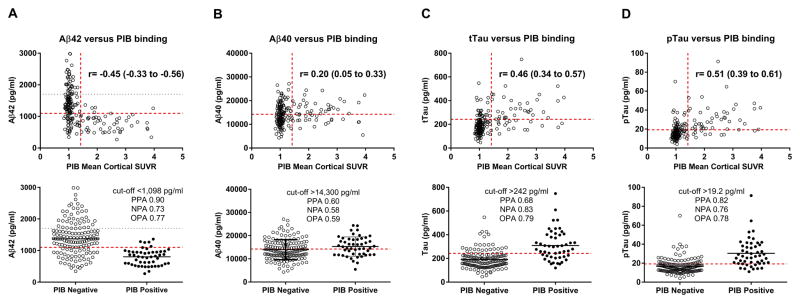

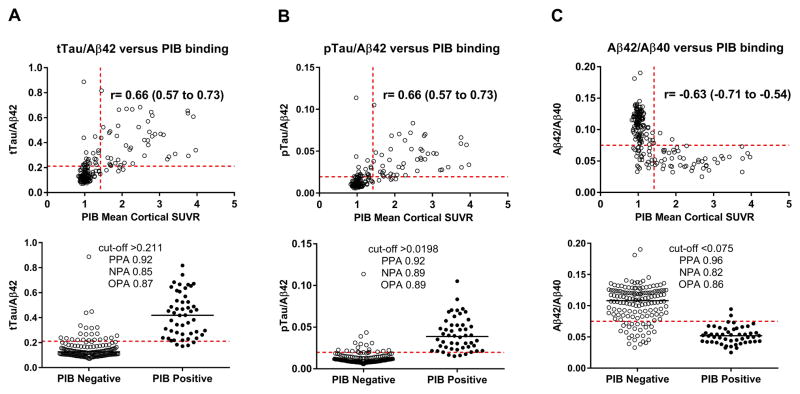

The Elecsys cobas e 601analyzer was used to measure levels of Aβ42, tTau and pTau. At the time of analysis, this platform did not have an Aβ40 assay available. Therefore, Aβ40 levels were measured with the IBL Aβ40 ELISA kit. The values for Aβ42, Aβ40, tTau or pTau were plotted versus PIB mean cortical SUVR (Fig. 1, upper panels). By Spearman correlation analysis, PIB binding was negatively correlated with CSF Aβ42 (r=−0.45, p<0.0001) and positively correlated with CSF Aβ40 (r=0.20, p<0.01), tTau (r=0.46, p<0.0001) and pTau (r=0.51, p<0.0001). PIB binding was positively correlated with tTau/Aβ42 (r=0.66), pTau/Aβ42 (r=0.66), and negatively correlated with Aβ42/Aβ40 (r=−0.63), all at p<0.0001 (Fig. 2, upper panels). Notably, tTau and pTau were almost perfectly correlated (r=0.98, p<0.0001).

Fig. 1. Single CSF analyte values compared to PIB binding.

PIB binding was negatively correlated with CSF Aβ42 (A) and positively correlated with CSF Aβ40 (B), tTau (C) and pTau (D). Each point represents the analyte value and PIB mean cortical SUVR for one individual. The horizontal red dashed lines represent the cut-off values that best distinguish between PIB-positive and PIB-negative individuals. The horizontal grey dotted line represents the upper limit of quantitation for Aβ42 (A). For the upper panels, the vertical red dashed lines represent the established cut-off value for PIB positivity (SUVR>1.42). The Spearman correlation coefficient (r) with 95% confidence intervals is indicated. For the lower panels, individuals were dichotomized into PIB negative (SUVR≤1.42) and PIB positive (SUVR>1.42) groups. The lower panels indicate the cut-off values and associated positive percent agreement (PPA), negative percent agreement (NPA) and overall percent agreement (OPA) for each CSF analyte with PIB binding.

Fig. 2. CSF ratios compared to PIB binding.

PIB binding is positively correlated with CSF tTau/Aβ42 (A), pTau/Aβ42 (B), and Aβ42/Aβ40 (C). Each point represents the ratio of analytes and PIB mean cortical SUVR for one individual. The horizontal red dashed lines represent the cut-off values that best distinguish between PIB-positive and PIB-negative individuals. For the upper panels, the vertical red dashed lines represent the established cut-off value for PIB positivity (SUVR>1.42). The Spearman correlation coefficient (r) with 95% confidence intervals is indicated. For the lower panels, individuals were dichotomized into PIB negative (SUVR≤1.42) and PIB-positive (SUVR>1.42) groups. The lower panels indicate the cut-off values and associated positive percent agreement (PPA), negative percent agreement (NPA) and overall percent agreement (OPA) for each CSF analyte with PIB binding.

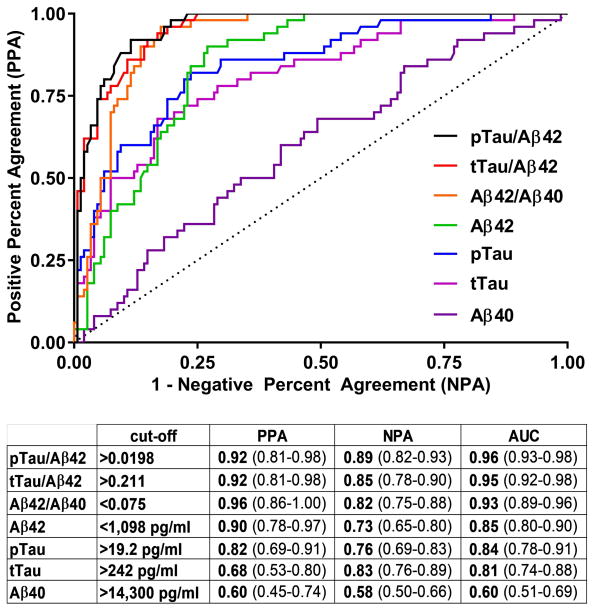

3.3. Determination of cut-offs for CSF biomarker measures

ROC analyses were performed to determine the cut-offs for each biomarker analyte and ratio that best distinguished PIB status (positive or negative). Because PIB PET is not the gold standard for brain amyloid deposition (autopsy is the gold standard), we refer to positive percent agreement (PPA) rather than sensitivity and negative percent agreement (NPA) rather than specificity. The cut-offs selected are depicted in the lower panels of Fig. 1 for Aβ42 (A), Aβ40 (B), tTau (C) and pTau (D) and Fig. 2 for tTau/Aβ42 (A), pTau/Aβ42 (B), and Aβ42/Aβ40 (C). The lower panels also indicate the associated PPA, NPA and OPA for each CSF measure with PIB status. The ROC curves and a summary of cut-off characteristics for all biomarker measures are shown in Fig. 3. Inspection of the ROC curves shows that Aβ42/Aβ40 and Aβ42 have a lower NPA for a given PPA at most potential cut-off values compared to the other ratios or single analytes, respectively (e.g., at a cut-point with a PPA of 0.50 for all analytes, the NPA for Aβ42/Aβ40 is lower than for tTau/Aβ42 and pTau/Aβ42 and the NPA for Aβ42 is lower than for tTau and pTau). For the cut-off values selected, the PPAs for tTau/Aβ42, pTau/Aβ42, and Aβ42/Aβ40 were high (0.92–0.96) with somewhat lower NPAs (0.82–0.89). The PPA and NPA for Aβ42, tTau and pTau as single analytes (0.68–0.90 for PPA and 0.73–0.83 for NPA) were not as high as the three ratios, but were superior to Aβ40 (0.60 for PPA and 0.58 for NPA).

Fig. 3. Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) curves for CSF biomarkers compared to PIB binding.

For ROC analysis, individuals were dichotomized into PIB-negative (SUVR≤1.42) and PIB-positive (SUVR>1.42) groups. For each CSF biomarker measure, the table indicates the cut-off values and associated positive percent agreement (PPA), negative percent agreement (NPA) and area under the ROC curve (AUC) for the measure compared to PIB status. 95% confidence intervals are included in parentheses.

Levels of Aβ42 >1,700 pg/ml were extrapolated and therefore estimated, so we performed alternative analyses to determine whether inaccuracies in high Aβ42 values could bias our results. We reanalyzed our data treating individuals with Aβ42 >1,700 pg/ml as biomarker negative, regardless of the level of other analytes (Supplemental Fig. 1). Notably, all 40 individuals in our cohort with Aβ42 values >1,700 pg/ml were PIB-negative. We found minimal changes in the results, likely because individuals with Aβ42 >1,700 pg/ml typically do not have significant AD brain pathology and therefore rarely have elevated tTau or pTau. The only small differences we found were that the NPA for tTau/Aβ42 increased from 0.85 to 0.86 and the NPA for Aβ42/Aβ40 increased from 0.82 to 0.83 when individuals with Aβ42 >1,700 pg/ml were considered biomarker negative. We therefore concluded that estimation of Aβ42 values >1,700 pg/ml did not affect concordance with PIB PET.

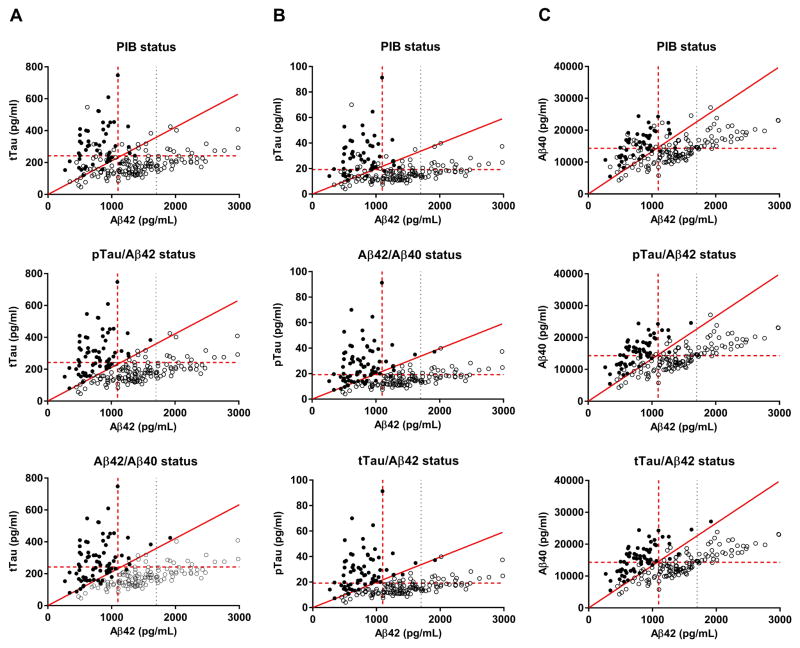

3.4. Concordance of CSF ratios and PIB binding

Since the three CSF ratios (tTau/Aβ42, pTau/Aβ42, and Aβ42/Aβ40) performed well in discriminating PIB-positive and PIB-negative individuals, we next examined the degree to which the CSF ratios were concordant with other CSF ratios and with PIB status (Table 2). Biomarker status (positive or negative according to the cut-offs previously discussed) was visualized in scatterplots of CSF tTau versus Aβ42 (Fig. 4A), pTau versus Aβ42 (B), and Aβ40 versus Aβ42 (C). There was concordance of all three CSF ratios and PIB PET in 166 of 198 individuals in our cohort (84%): all three CSF ratios were positive in 46 of the 50 PIB-positive individuals (92%) and all three CSF ratios were negative in 120 of the 148 PIB-negative individuals (81%). Four individuals were PIB-positive but either all three CSF ratios were negative (two individuals) or Aβ42/Aβ40 was positive but tTau/Aβ42 and pTau/Aβ42 were negative (two individuals). Sixteen individuals were PIB-negative but all three CSF ratios were positive. Twelve individuals were PIB-negative and had partial discordance of the CSF ratios; most (ten of twelve) had high Aβ42/Aβ40.

Table 2.

Concordance between CSF tTau/Aβ42, pTau/Aβ42, Aβ42/Aβ40 and PIB PET.

| n (% of PiB group) | CDR | PIB SUVR | tTau/Aβ42 | pTau/Aβ42 | Aβ42/Aβ40 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0/0.5/1/2/3 | >1.42 | >0.211 | >0.0198 | <0.075 | ||

| PiB positive, n=50 | ||||||

| PIB + and all CSF ratios + | 46 (92%) | 31/11/3/1/0 | 2.45 ± 0.71 | 0.440 ± 0.165 | 0.0434 ± 0.0194 | 0.050 ± 0.011 |

| PIB +, all CSF ratios − | 2 (4%) | 2/0/0/0/0 | 1.74 ± 0.23 | 0.175 ± 0.005 | 0.0156 ± 0.0006 | 0.089 ± 0.007 |

| tTau/Aβ42 and pTau/Aβ42 −, Aβ42/Aβ40 + | 2 (4%) | 2/0/0/0/0 | 1.98 ± 0.07 | 0.193 ± 0.012 | 0.0172 ± 0.0006 | 0.069 ± 0.003 |

| PiB negative, n=148 | ||||||

| All CSF ratios − | 120 (81%) | 114/6/0/0/0 | 1.03 ± 0.10 | 0.120 ± 0.030 | 0.0104 ± 0.0026 | 0.114 ± 0.019 |

| All CSF ratios + | 16 (11%) | 16/0/0/0/0 | 1.16 ± 0.14 | 0.334 ± 0.162 | 0.0322 ± 0.0228 | 0.050 ± 0.011 |

| Aβ42/Aβ40 +, tTau/Aβ42 and pTau/Aβ42 − | 6 (4%) | 6/0/0/0/0 | 0.98 ± 0.08 | 0.189 ± 0.013 | 0.0165 ± 0.0019 | 0.067 ± 0.005 |

| Aβ42/Aβ40 and tTau/Aβ42 +, pTau/Aβ42 − | 4 (3%) | 3/1/0/0/0 | 1.06 ± 0.16 | 0.222 ± 0.003 | 0.0192 ± 0.0003 | 0.066 ± 0.007 |

| tTau/Aβ42 and pTau/Aβ42 +, Aβ42/Aβ40 − | 1 (1%) | 1/0/0/0/0 | 1.05 | 0.222 | 0.0203 | 0.083 |

| tTau/Aβ42 +, Aβ42/Aβ40 and pTau/Aβ42 − | 1 (1%) | 1/0/0/0/0 | 1.32 | 0.223 | 0.0183 | 0.084 |

Fig. 4. Concordance of CSF ratios and PIB binding.

The status (positive or negative according to CSF ratios or PIB binding) was evaluated in scatterplots of CSF tTau versus Aβ42 (A), pTau versus Aβ42 (B), and Aβ40 versus Aβ42 (C). Each point represents CSF biomarkers in one individual. Solid points have a positive biomarker status (as defined in the plot titles) and open points have a negative status. The horizontal red dashed lines represent the cut-off values for CSF tTau (A), pTau (B) and Aβ40 (C). The vertical red dashed lines represent the cut-off value for Aβ42. The vertical grey dotted lines represent the upper limit of quantitation for Aβ42. The sloped solid red lines represent the cut-off values for tTau/Aβ42 (A), pTau/Aβ42 (B), and Aβ40/Aβ42 (C).

There was concordance of PIB PET and all three CSF ratios in 21 of the 22 individuals in our cohort with cognitive impairment (CDR>0): Fifteen individuals were positive by all measures and six were negative by all measures. One individual rated CDR 0.5 was PIB-negative, Aβ42/Aβ40 and tTau/Aβ42 positive but pTau/Aβ42 negative. The six individuals rated CDR>0 who were negative by both PET PIB and all three CSF ratios likely have a non-AD cause of their cognitive symptoms. In all 198 cases, tTau/Aβ42 was positive if pTau/Aβ42 was positive, but tTau/Aβ42 was positive in some individuals (n=5) when pTau/Aβ42 was negative. Notably, many of the individuals with partial discordance of the CSF ratios had values close to the cut-offs and therefore may be in a transitional or borderline stage (see Table 2).

4. Discussion

Overall we found a high concordance between PIB PET and CSF biomarkers of AD as measured by the automated Elecsys cobas e 601 analyzer. Ratios of CSF biomarkers that included Aβ42 (tTau/Aβ42, pTau/Aβ42 and Aβ42/Aβ40) best distinguished PIB-positive from PIB-negative individuals. All three CSF ratios were positive in 46 of the 50 PIB-positive individuals (92%) and all three CSF ratios were negative in 120 of the 148 PIB-negative individuals (81%). Out of the 32 individuals (16% of the cohort) with discordance between the three CSF ratios and PIB PET, 28 individuals were negative by PIB but positive by at least one CSF ratio.

Previous reports have identified amyloid PET negative individuals with positive CSF biomarkers [3, 5, 6, 42]. Recent work has demonstrated that amyloid PET negative but CSF biomarker positive individuals have increased rates of amyloid accumulation, suggesting these individuals have early AD brain pathology and are likely to develop amyloid PET positivity [3, 42]. While CSF biomarkers and amyloid PET are both markers of amyloid pathology, CSF biomarkers indicate the state of Aβ42 production and clearance at the time of LP while amyloid PET images the accumulation of neuritic amyloid plaques over many years. Additionally, amyloid PET tracers are designed to bind to neuritic amyloid plaques [47], whereas CSF biomarkers could be more sensitive to deposition of both neuritic amyloid plaques and diffuse amyloid plaques [48]. It appears likely that CSF biomarkers become positive very early in the course of the disease, before sufficient amyloid has accumulated to create an amyloid PET signal. Therefore, less than perfect correspondence of PIB PET and CSF biomarkers is expected and may reflect differences in AD brain pathology.

Notably, we found that in cases of partial discordance between CSF biomarker ratios and PIB PET (when some, but not all, CSF biomarker ratios agreed with PIB PET), Aβ42/Aβ40 was typically the positive ratio (nine of eleven cases) in PIB-negative cases and was the sole positive ratio in two PIB-positive cases. These findings suggest that abnormal Aβ42/Aβ40 may be the earliest indicator of amyloid brain pathology, potentially reflecting stage one of preclinical AD (amyloid deposition but no abnormalities in tTau or pTau) [49]. Compared to Aβ42, the ratio of Aβ42/Aβ40 may better reflect deposition of amyloid because it may normalize for individual variation in overall amyloid production [24]. However, many of the cases with partial discordance of CSF ratios have borderline values and selecting different cut-offs would change the concordance of the ratios somewhat. Larger studies are required to determine whether Aβ42/Aβ40 becomes altered at an earlier stage than tTau/Aβ42 and pTau/Aβ42. Interestingly, we also found that tTau and pTau were almost perfectly correlated (r=0.98, p<0.0001) in our cohort. It is possible that tTau and pTau may be less highly correlated in a cohort enriched for non-AD dementia—this is a topic for future studies.

The Roche Elecsys cobas e 601 analyzer and other automated assays for CSF biomarkers are likely to increase the utility of CSF biomarkers in research, clinical trials and clinical diagnosis. Further studies are needed to examine the concordance between CSF biomarkers of AD as measured by the Elecsys cobas e 601 analyzer and other amyloid PET tracers. Studies are also needed to evaluate whether CSF biomarkers of AD as measured by the Elecsys cobas e 601 analyzer predict future cognitive decline. It is unclear whether the same cut-off values that correspond with amyloid PET status will also best predict cognitive decline. Finally, comparison of CSF biomarkers with brain autopsy data in cases with a short CSF collection to autopsy interval would be helpful in demonstrating that CSF biomarkers as measured by the Elecsys cobas e 601 analyzer are strongly correlated with AD brain pathology.

Given the high degree of precision, accuracy, reliability and reproducibility of the Elecsys cobas e 601 analyzer [39], it is possible that an Elecsys CSF biomarker measure could be found that is reproducible across all sites worldwide and is highly predictive of AD brain pathology. It is important to note that pre-analytical factors may affect CSF biomarker values, especially of Aβ42. Therefore, further refinement of CSF testing for AD will require rigorous standardization of pre-analytical factors, including sample collection and processing. It will also be important to further define when it is appropriate for clinicians to perform CSF testing for AD. When a disease modifying agent for AD becomes available, many patients will be interested in learning their amyloid status, and it will be important to have clear guidelines in place for all aspects of CSF testing.

HIGHLIGHTS.

CSF biomarkers of AD were measured with the Roche Elecsys assay

tTau/Aβ42, pTau/Aβ42 and Aβ42/Aβ40 best distinguished PIB PET status

All three CSF ratios were positive in 92% of PIB-positive individuals

All three CSF ratios were negative in 81% of PIB-negative individuals

CSF biomarkers may detect AD pathology earlier than amyloid PET

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Systematic review: Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers of Alzheimer disease (AD) are used in research, clinical trials and to inform clinical diagnosis. Technical factors, including lot-to-lot variability in assays, have limited the utility of CSF assays.

Interpretation: CSF biomarker values measured with the automated Roche Elecsys cobas e 601 analyzer were compared to PIB PET. We found that ratios of CSF biomarkers that included Aβ42 (tTau/Aβ42, pTau/Aβ42 and Aβ42/Aβ40) best distinguished between individuals who were PIB-positive and PIB-negative. Discordance between CSF biomarkers and PIB PET may occur because CSF biomarkers measure different aspects of AD brain pathology.

Future directions: Automated assays for CSF biomarkers are likely to improve the reliability of CSF testing for AD. Further work is needed to standardize pre-analytical factors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the research volunteers who participated in the studies from which these data were obtained and their supportive families. We would like to thank the Clinical, Biomarker and Imaging Cores at the Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center for sample and data collection. We thank Sandra Rutz and Valeria Lifke at Roche Diagnostics GmbH, who were the Development Leads for the Aβ42 and tTau/pTau assays, respectively. This study was supported by National Institute on Aging grants P01AG026276, P01AG03991, and P50AG05681 (JC Morris, PI) and a research grant from Roche Diagnostics (AM Fagan, PI). Additional support for imaging was provided by the Barnes Jewish Hospital Foundation and the NIH P30NS098577, R01EB009352, and UL1TR000448.

Abbreviations

- Aβ42

amyloid-β peptide 42

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- AUC

area under the curve

- CDR

Clinical Dementia Rating

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- LP

lumbar puncture

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PIB

Pittsburgh Compound B

- pTau

phosphorylated Tau-181

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- SUVR

standardized uptake value ratio

- tTau

total Tau

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Schindler is currently supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants K23AG053426 and R03AG050921. During part of this study she was supported by UL1 TR00448, Sub-Award KL2 TR000450. She has a family member with stock in Eli Lilly. Ms. Gray reports no conflicts. Dr. Gordon reports no conflicts. Dr. Xiong is supported by NIH grants R01AG034119 and R01AG053550. Dr. Batrla-Utermann, Ms. Quan, and Dr. Wahl are employees of Roche Diagnostics, the developer and manufacturer of the Elecsys assay. Dr. Benzinger has investigator initiated research funded by Avid Radiopharmaceuticals (a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly), and is an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Roche, Jansen, and Biogen. Dr. Holtzman co-founded and is on the scientific advisory board of C2N Diagnostics. He consults for Genentech, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Proclara, Glaxosmithkline, and Denali. Washington University receives research grants to the lab of Dr. Holtzman from C2N Diagnostics, Eli Lilly, AbbVie, and Denali. Dr. Morris has served as a consultant for Lilly USA and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Morris receives research support from Eli Lilly/Avid Radiopharmaceuticals and is funded by NIH grants P50AG005681, P01AG003991, P01AG026276 and UF01AG032438. Dr. Fagan is supported by NIH grants including P50AG005681, P01AG003991, P01AG026276 and UF01AG03243807. She is on the Scientific Advisory Boards for Roche Diagnostics, IBL International and AbbVie and consults for Biogen, DiamiR, LabCorp and Araclon Biotech/Griffols.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Price JL, Morris JC. Tangles and plaques in nondemented aging and “preclinical” Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of neurology. 1999;45:358–68. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199903)45:3<358::aid-ana12>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price JL, McKeel DW, Jr, Buckles VD, Roe CM, Xiong C, Grundman M, et al. Neuropathology of nondemented aging: presumptive evidence for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurobiology of aging. 2009;30:1026–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmqvist S, Mattsson N, Hansson O Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis detects cerebral amyloid-beta accumulation earlier than positron emission tomography. Brain: a journal of neurology. 2016;139:1226–36. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, Goate A, Fox NC, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367:795–804. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, Lee SY, Dence CS, Shah AR, et al. Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Abeta42 in humans. Annals of neurology. 2006;59:512–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Shah AR, Aldea P, Roe CM, Mach RH, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid tau and ptau(181) increase with cortical amyloid deposition in cognitively normal individuals: implications for future clinical trials of Alzheimer’s disease. EMBO molecular medicine. 2009;1:371–80. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagan AM, Roe CM, Xiong C, Mintun MA, Morris JC, Holtzman DM. Cerebrospinal fluid tau/beta-amyloid(42) ratio as a prediction of cognitive decline in nondemented older adults. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:343–9. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.3.noc60123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li G, Sokal I, Quinn JF, Leverenz JB, Brodey M, Schellenberg GD, et al. CSF tau/Abeta42 ratio for increased risk of mild cognitive impairment: a follow-up study. Neurology. 2007;69:631–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000267428.62582.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duits FH, Teunissen CE, Bouwman FH, Visser PJ, Mattsson N, Zetterberg H, et al. The cerebrospinal fluid “Alzheimer profile”: easily said, but what does it mean? Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2014;10:713–23e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brys M, Pirraglia E, Rich K, Rolstad S, Mosconi L, Switalski R, et al. Prediction and longitudinal study of CSF biomarkers in mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiology of aging. 2009;30:682–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansson O, Zetterberg H, Buchhave P, Londos E, Blennow K, Minthon L. Association between CSF biomarkers and incipient Alzheimer’s disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a follow-up study. The Lancet Neurology. 2006;5:228–34. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, Figurski M, Coart E, Blennow K, et al. Qualification of the analytical and clinical performance of CSF biomarker analyses in ADNI. Acta neuropathologica. 2011;121:597–609. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0808-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beach TG, Monsell SE, Phillips LE, Kukull W. Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease at National Institute on Aging Alzheimer Disease Centers, 2005–2010. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2012;71:266–73. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31824b211b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molinuevo JL, Blennow K, Dubois B, Engelborghs S, Lewczuk P, Perret-Liaudet A, et al. The clinical use of cerebrospinal fluid biomarker testing for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis: a consensus paper from the Alzheimer’s Biomarkers Standardization Initiative. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2014;10:808–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris JC, Selkoe DJ. Recommendations for the incorporation of biomarkers into Alzheimer clinical trials: an overview. Neurobiology of aging. 2011;32(Suppl 1):S1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hampel H, Wilcock G, Andrieu S, Aisen P, Blennow K, Broich K, et al. Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease therapeutic trials. Progress in neurobiology. 2011;95:579–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Tan L, Yu JT. Prevention Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD. 2016;50:927–45. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sperling RA, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Karlawish J, Donohue M, Salmon DP, et al. The A4 study: stopping AD before symptoms begin? Science translational medicine. 2014;6:228fs13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galasko D, Chang L, Motter R, Clark CM, Kaye J, Knopman D, et al. High cerebrospinal fluid tau and low amyloid beta42 levels in the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease and relation to apolipoprotein E genotype. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:937–45. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.7.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frisoni GB, Bocchetta M, Chetelat G, Rabinovici GD, de Leon MJ, Kaye J, et al. Imaging markers for Alzheimer disease: which vs how. Neurology. 2013;81:487–500. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829d86e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, Wang Y, Blomqvist G, Holt DP, et al. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Annals of neurology. 2004;55:306–19. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Witte MM, Foster NL, Fleisher AS, Williams MM, Quaid K, Wasserman M, et al. Clinical use of amyloid-positron emission tomography neuroimaging: Practical and bioethical considerations. Alzheimer’s & dementia. 2015;1:358–67. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Brien JT, Herholz K. Amyloid imaging for dementia in clinical practice. BMC medicine. 2015;13:163. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0404-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewczuk P, Matzen A, Blennow K, Parnetti L, Molinuevo JL, Eusebi P, et al. Cerebrospinal Fluid Abeta42/40 Corresponds Better than Abeta42 to Amyloid PET in Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD. 2017;55:813–22. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grimmer T, Riemenschneider M, Forstl H, Henriksen G, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, et al. Beta amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease: increased deposition in brain is reflected in reduced concentration in cerebrospinal fluid. Biological psychiatry. 2009;65:927–34. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jagust WJ, Landau SM, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Koeppe RA, Reiman EM, et al. Relationships between biomarkers in aging and dementia. Neurology. 2009;73:1193–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bc010c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landau SM, Lu M, Joshi AD, Pontecorvo M, Mintun MA, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Comparing positron emission tomography imaging and cerebrospinal fluid measurements of beta-amyloid. Annals of neurology. 2013;74:826–36. doi: 10.1002/ana.23908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mattsson N, Insel PS, Landau S, Jagust W, Donohue M, Shaw LM, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of CSF Ab42 and florbetapir PET for Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of clinical and translational neurology. 2014;1:534–43. doi: 10.1002/acn3.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmqvist S, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Vestberg S, Andreasson U, Brooks DJ, et al. Accuracy of brain amyloid detection in clinical practice using cerebrospinal fluid beta-amyloid 42: a cross-validation study against amyloid positron emission tomography. JAMA neurology. 2014;71:1282–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmqvist S, Zetterberg H, Mattsson N, Johansson P, Minthon L, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. Detailed comparison of amyloid PET and CSF biomarkers for identifying early Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2015;85:1240–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tolboom N, van der Flier WM, Yaqub M, Boellaard R, Verwey NA, Blankenstein MA, et al. Relationship of cerebrospinal fluid markers to 11C-PiB and 18F-FDDNP binding. Journal of nuclear medicine: official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2009;50:1464–70. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.064360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fagan AM, Shaw LM, Xiong C, Vanderstichele H, Mintun MA, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Comparison of analytical platforms for cerebrospinal fluid measures of beta-amyloid 1-42, total tau, and p-tau181 for identifying Alzheimer disease amyloid plaque pathology. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1137–44. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vos SJB, Gordon BA, Su Y, Visser PJ, Holtzman DM, Morris JC, et al. NIA-AA staging of preclinical Alzheimer disease: discordance and concordance of CSF and imaging biomarkers. Neurobiology of aging. 2016;44:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vos SJ, Visser PJ, Verhey F, Aalten P, Knol D, Ramakers I, et al. Variability of CSF Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers: implications for clinical practice. PloS one. 2014;9:e100784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mattsson N, Andreasson U, Persson S, Arai H, Batish SD, Bernardini S, et al. The Alzheimer’s Association external quality control program for cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2011;7:386–95. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mattsson N, Andreasson U, Persson S, Carrillo MC, Collins S, Chalbot S, et al. CSF biomarker variability in the Alzheimer’s Association quality control program. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2013;9:251–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schindler SE, Sutphen CL, Teunissen C, McCue LM, Morris JC, Holtzman DM, et al. Upward drift in cerebrospinal fluid amyloid beta 42 assay values for more than 10 years. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.06.2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mattsson N, Zegers I, Andreasson U, Bjerke M, Blankenstein MA, Bowser R, et al. Reference measurement procedures for Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers: definitions and approaches with focus on amyloid beta42. Biomarkers in medicine. 2012;6:409–17. doi: 10.2217/bmm.12.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bittner T, Zetterberg H, Teunissen CE, Ostlund RE, Jr, Militello M, Andreasson U, et al. Technical performance of a novel, fully automated electrochemiluminescence immunoassay for the quantitation of beta-amyloid (1-42) in human cerebrospinal fluid. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2016;12:517–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pastor P, Roe CM, Villegas A, Bedoya G, Chakraverty S, Garcia G, et al. Apolipoprotein Eepsilon4 modifies Alzheimer’s disease onset in an E280A PS1 kindred. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:163–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.10636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vlassenko AG, McCue L, Jasielec MS, Su Y, Gordon BA, Xiong C, et al. Imaging and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in early preclinical alzheimer disease. Annals of neurology. 2016;80:379–87. doi: 10.1002/ana.24719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mintun MA, Larossa GN, Sheline YI, Dence CS, Lee SY, Mach RH, et al. [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67:446–52. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228230.26044.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fischl B, van der Kouwe A, Destrieux C, Halgren E, Segonne F, Salat DH, et al. Automatically parcellating the human cerebral cortex. Cerebral cortex. 2004;14:11–22. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Su Y, D’Angelo GM, Vlassenko AG, Zhou G, Snyder AZ, Marcus DS, et al. Quantitative analysis of PiB-PET with FreeSurfer ROIs. PloS one. 2013;8:e73377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Su Y, Blazey TM, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME, Marcus DS, Ances BM, et al. Partial volume correction in quantitative amyloid imaging. NeuroImage. 2015;107:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clark CM, Pontecorvo MJ, Beach TG, Bedell BJ, Coleman RE, Doraiswamy PM, et al. Cerebral PET with florbetapir compared with neuropathology at autopsy for detection of neuritic amyloid-beta plaques: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet Neurology. 2012;11:669–78. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cairns NJ, Ikonomovic MD, Benzinger T, Storandt M, Fagan AM, Shah AR, et al. Absence of Pittsburgh compound B detection of cerebral amyloid beta in a patient with clinical, cognitive, and cerebrospinal fluid markers of Alzheimer disease: a case report. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1557–62. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2011;7:280–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]