Abstract

Co-ordinated interaction between distinct cell types is a hallmark of successful immune function. A striking example of this is the carefully orchestrated cooperation between helper T cells and B cells that occurs during the initiation and fine-tuning of T-cell dependent antibody responses. While these processes have evolved to permit rapid immune defense against infection, it is becoming increasingly clear that such interactions can also underpin the development of autoimmunity. Here we discuss a selection of cellular and molecular pathways that mediate T cell/B cell collaboration and highlight how in vivo models and genome wide association studies link them with autoimmune disease. In particular, we emphasize how CTLA-4-mediated regulation of CD28 signaling controls the engagement of secondary costimulatory pathways such as ICOS and OX40, and profoundly influences the capacity of T cells to provide B cell help. While our molecular understanding of the co-operation between T cells and B cells derives from analysis of secondary lymphoid tissues, emerging evidence suggests that subtly different rules may govern the interaction of T and B cells at ectopic sites during autoimmune inflammation. Accordingly, the phenotype of the T cells providing help at these sites includes notable distinctions, despite sharing core features with T cells imparting help in secondary lymphoid tissues. Finally, we highlight the interdependence of T cell and B cell responses and suggest that a significant beneficial impact of B cell depletion in autoimmune settings may be its detrimental effect on T cells engaged in molecular conversation with B cells.

Keywords: follicular helper T cells (Tfh), B cells, germinal center, autoimmunity, costimulation, CD28, CTLA-4, immunotherapy

Introduction

Effective collaboration between T and B cells is a central tenet of protective immunity. Such interactions underlie the development of optimal affinity-matured antibody responses that are required for host defense, permitting the rapid neutralization of bacterial toxins and blockade of viral cell entry. Over the last decade however, it has become apparent that T cell/B cell collaboration also underpins the development of many autoimmune responses leading to undesirable sequelae. Thus, many of the cellular and molecular pathways familiar to us in the context of effective immunity are also implicated in the development of autoimmunity.

In this review we highlight the interdependence of T cell and B cell responses, both in the initiation of humoral immunity and in the context of immune memory. We then home in on the pathways supporting T cell/B cell collaboration and discuss how costimulatory signals orchestrate the chemokine receptor modulation that drives T cell localization to the T-B border and the altered motility that promotes follicular entry. The importance of SLAM family members in stabilizing adhesive interactions between T and B cells is considered, as is the role of cytokines that support or hinder the emergence of T cell help for the B cell response. Next we examine the early work linking follicular helper T cell (Tfh) differentiation to the development of autoimmunity in mice and describe how this prompted a wave of interest in the analysis of blood-borne Tfh-like cells in human autoimmunity. We illustrate how many of the pathways considered earlier are linked to human autoimmunity by probing GWAS datasets for 10 selected autoimmune diseases.

Throughout the review we focus in particular on the Tfh cell subset that enter B cell follicles to support germinal center (GC) formation. However, it is important to note that interactions between B cells and non-Tfh subsets may also play roles in promoting autoimmunity. A recent exciting development in this regard is covered in our final section on T Cell/B Cell Collaboration Outside Secondary Lymphoid Tissues where we discuss the identification of “peripheral helper” T cells that lack bona fide Tfh markers yet appear to provide help to B cells at sites of autoimmune inflammation. Finally, we close the article by discussing the potential to interrupt T cell/B cell collaboration in autoimmune settings by therapeutic B cell depletion.

Interdependence of T cell and B cell responses

Implicit in the concept of T cell help for B cells is a notion of directionality, implying that T cells are the providers of help and B cells the recipients. However, it has become clear that the reality is far more equitable, with sequential inputs required from both cell types for a successful overall outcome. This is elegantly demonstrated by the molecular underpinnings of the germinal center response, which relies on tightly regulated bi-directional interactions between follicular helper T cells (Tfh) and B cells.

Tfh cell differentiation is a highly complex multistage endeavor [reviewed in (1)], and B cells play an integral role in this process from the moment Tfh cell precursors first interact with B cells at the follicular border in spleen or interfollicular region in lymph nodes (2, 3) and throughout the GC reaction. In the absence of cognate B cells, Tfh precursors expressing Bcl6 (the master transcription factor for Tfh differentiation) fail to assume a mature Tfh cell phenotype within the follicle (3). The maintenance of Tfh cells requires sustained antigenic stimulation and B cells represent the key antigen presenting cell type during the GC reaction (4, 5). Moreover, there is a positive correlation between Tfh cell and GC B cell numbers in GC, emphasizing the intimate functional relationship between the two cell subsets (4, 6).

When it comes to memory responses, T cells play a clear role in the emergence of memory B cells via the GC reaction, and it appears that the inverse is also true, with B cells actively supporting the efficient generation or maintenance of T cell memory (7). Elegant experiments revealed a key role for memory B cells in presenting antigen to memory Tfh cells to drive Bcl6 re-expression (8), and the location of memory Tfh cells in B cell follicles (9, 10) makes them ideally placed for such contacts. In addition to cognate interaction, the role of B cells in T cell memory may include the provision of costimulatory ligands, as well as their contribution to the structural organization and architecture that supports immune responses.

Pathways supporting T cell/B cell collaboration

Several key pathways regulating T cell/B cell collaboration have been identified over the years (11), and we highlight a number of examples below.

CD40/CD40L

CD40 and CD40L have long been recognized as key players in humoral immunity and are essential for GC formation (11–13). Blockade of CD40L signaling during an ongoing GC reaction was shown to abrogate the response, emphasizing the need for continuous CD40-CD40L interactions throughout the GC lifespan (14). Clinical studies identified mutations in CD40L as a common cause for human genetic immunodeficiency X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome, where patients presented with impaired GC development emphasizing the importance of T cell/B cell collaboration in the pre-GC stages of adaptive immune responses (11, 15).

CD28/CTLA-4

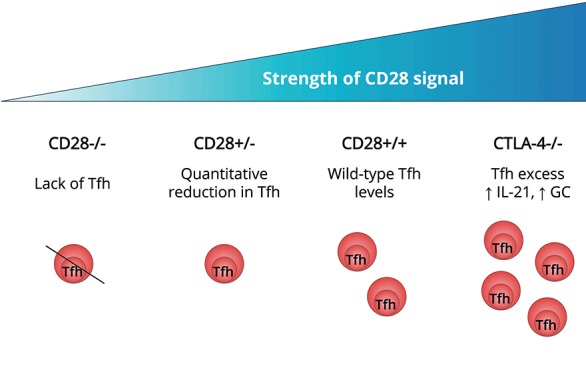

Experiments in the late 1990's established that CD28 signaling was required for CD4 T cells to upregulate CXCR5 and migrate into B cell follicles (16), explaining the defect in GC formation in mice lacking CD28 (17) or its ligands (18). CXCR5 induction permits responsiveness to CXCL13 expressed by stromal cells in the follicle and, in association with downregulation of CCR7 (19), guides T cell follicular migration. The G-protein-coupled receptor S1PR2 appears to cooperate with CXCR5 to ensure localization and retention of Tfh at the GC site (20). The amount of CD28 engagement directly influences Tfh differentiation since T cells heterozygous for CD28 showed reduced Tfh induction despite normal activation (Figure 1). The CD28 pathway is regulated by CTLA-4 which binds to the same ligands, CD80 and CD86, but with higher affinity than CD28. Although widely credited with imparting a negative signal, in our view the available evidence does not support this idea and instead suggests that CTLA-4 regulates CD28 engagement by competing for and downregulating their shared ligands (22, 23). The CTLA-4 pathway restricts the formation of Tfh by limiting T cell CD28 engagement (21) and CTLA-4 expression in the regulatory T cell compartment is essential for this process (24, 25). Accordingly, deficiency or blockade of CTLA-4 in mice leads to hyper-engagement of CD28, overproduction of Tfh and spontaneous GC formation (21). CD28 is also required for the development of the follicular regulatory T cells (Tfr) that negatively regulate the GC response (26) (for recent reviews of Tfr please see Wing et al. (27), Fazilleau and Aloulou (28) and Xie and Dent (29) in this collection).

Figure 1.

Strength of T cell CD28 engagement influences Tfh differentiation. In mice that are deficient in CD28 signaling, T cells fail to form Tfh (16–18). T cells expressing less CD28, as a result of gene heterozygosity, exhibit a quantitative reduction in Tfh generation compared with wildtype T cells (21). In mice lacking CTLA-4, regulation of CD80 and CD86 is impaired resulting in excessive CD28 engagement. This is associated with spontaneous Tfh induction, increased T cell IL-21 production and formation of germinal centers (21).

OX40

The ability of CD28 to promote Tfh development may reflect its capacity to upregulate secondary costimulatory receptors such as OX40 and ICOS. CD28 engagement triggers T cell OX40 upregulation (16) and ligation of OX40 in turn promotes CXCR5 expression (30). Mice expressing OX40L constitutively on dendritic cells showed increased numbers of CD4 T cells in their B cell follicles (31) and conversely deficiency (32) or blockade (33) of OX40 reduced Tfh numbers after viral challenge. Importantly, B cell expression of OX40L has also been shown to support Tfh development (34).

Despite the above, the involvement of OX40 in Tfh differentiation remains controversial; indeed in one study engagement of OX40 was shown to impair Tfh development by promoting expression of Blimp-1 (35) which can inhibit Bcl6 and extinguish the Tfh programme (36). Similarly, in the context of Listeria monocytogenes infection, mice lacking OX40 showed intact Tfh differentiation, and treatment of wildtype mice with agonistic anti-OX40 antibodies expanded effector T cells at the expense of Tfh (37). Thus the involvement of OX40 may be context dependent, with strain-specific and site-specific differences being noted in one study (38). It remains possible that OX40 stimulates the survival or expansion of all differentiated T cells rather than instructing the Tfh differentiation process per se.

ICOS

ICOS is known to be required for the GC response (39–42) and its engagement promotes the differentiation (43) and maintenance (44) of Tfh cells. The level of ICOS upregulation on T cells undergoing activation in vivo is tightly coupled to the level of CD28 engagement (21) consistent with the idea that CD28 may promote GC formation via the ICOS pathway. ICOS is superior to CD28 in its capacity to activate phosphoinositide 3-kinase which is known to be required for Tfh cell differentiation and GC formation (6, 45). It has been suggested that ICOS can substitute for CD28 in later phases of the Tfh response (46) although the timing may be critical since extinguishing CD28 at the time of OX40 induction (using OX40-Cre CD28-floxed mice) showed the response was still CD28-dependent at this stage (47, 48). B cells may be an important source of ICOSL since mice lacking B cell-expression of this molecule exhibit significantly reduced Tfh and GC B cell numbers in response to peptide immunization (49, 50). Intriguingly this may reflect a role for ICOSL on bystander (non-cognate) B cells which engages ICOS on T cells approaching the T-B border, promoting their motility and hastening their follicular entry and subsequent Tfh maturation (51). ICOS signaling downregulates the transcription factor Klf2 in both mouse and human T cells and this is critical for ensuring follicular localization of Tfh by keeping CXCR5 high but CCR7, CD62L, PSGL-1, and S1PR1 low (44). Mirroring the findings in murine models, humans with ICOS deficiency show reduced blood Tfh cell frequencies and defects in GC and memory B cell formation (52, 53).

SLAM family members

During a GC reaction, T and B cells are required to repeatedly engage with each other to facilitate interactions between the receptor/ligand pairs described above. At the T-B border, early interactions between antigen-specific T and B cells are long-lived, while within GC, most cognate Tfh/GC B cell interactions last less than 5 min, but are associated with extensive surface contacts (54, 55). These interactions are stabilized by expression of signal lymphocyte activation molecule (SLAM) family receptors Ly108 and CD84 and SLAM-associated protein (SAP) (56, 57). The importance of these molecules is highlighted by SAP-deficient mice, where Tfh cell differentiation is impaired leading to profound defects in formation of GC, long-lived plasma cells and memory B cells (58–61). Similar observations have been made in X-linked lymphoproliferative disease patients with SAP-deficiency (62).

Cytokines

IL-2 is a powerful inhibitor of Tfh differentiation (43, 63) by virtue of its STAT5-dependent induction of Blimp-1 (43, 64). Intriguingly, it has been shown that activated dendritic cells in the outer T zone use CD25 expression to quench T cell derived IL-2 thereby generating a microenvironment that favors Tfh formation (65). Tfh differentiation is also influenced by other cytokines, most notably IL-6 in mice (66) and IL-12 in humans (67, 68). Intravital imaging studies have revealed that cognate interactions with GC B cells induce Ca2+-dependent co-expression of IL-21 and IL-4 in Tfh (69). These cytokines further promote GC B cell responses, providing a positive feedback loop between Tfh and GC B cells.

T cell/B cell collaboration in autoimmunity

Widespread recognition of the importance of T cell/B cell collaboration in driving immune-mediated pathology came from a landmark paper in 2009 (70) linking overproduction of Tfh with systemic autoimmunity. This work focused on sanroque mice which have a mutation in the E3 ubiquitin ligase Roquin-1 that regulates mRNA stability and is required for appropriate repression of ICOS expression. Mice with the Roquin mutation exhibited high ICOS expression, excessive Tfh formation and lupus-like pathology, however this was abolished if the mice were rendered SAP-deficient, consistent with a critical role for T cell/B cell collaboration in driving this pathology. It was subsequently shown that the Roquin mutation dramatically increased progression to type 1 diabetes (T1D) in a TCR transgenic mouse model (71). In a separate mouse model, microarray analysis of T cells responding to pancreatic antigen revealed a striking signature for Tfh differentiation, and cells with a Tfh phenotype showed an enhanced capacity to induce diabetes upon adoptive transfer (72). SAP dependent T cell/B cell interactions have been shown to be essential in the K/BxN model of arthritis (73), where a role for gut microbiota in promoting disease via Tfh induction has been identified (74). A separate study revealed that collagen-induced arthritis could be ameliorated by T cell specific CXCR5 deficiency consistent with the potential involvement of Tfh (75). Findings from mouse models prompted investigation of cells with a Tfh-like phenotype in a wide variety of disease settings in humans, leading to the appreciation that these cells are overrepresented in multiple autoimmune diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjögren's syndrome, T1D, myasthenia gravis, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and multiple sclerosis (MS) (76–78).

The exact provenance of blood-borne cells with a Tfh phenotype has been the subject of much debate. Elegant intravital imaging revealed that while Tfh readily move between GC they only rarely enter the circulation (79). It is widely recognized that Tfh have a circulating memory counterpart (80–83), however expression of many Tfh markers is reduced in the circulation (84, 85) with CXCR5 being least affected (4). Blood-borne CD4+CXCR5+ cells have been shown to be superior at supporting B cell antibody production and class-switching in vitro compared to their CD4+CXCR5- counterparts (86–90). Importantly, CXCR5+ cells can be found in the blood of SAP-deficient mice and humans, consistent with the idea that they arise prior to T cell differentiation into mature Tfh within GC (89). Despite their controversial origin and likely heterogeneity, it has become clear that upon antigen exposure circulating Tfh-phenotype cells can migrate to secondary lymphoid tissue and participate in GC reactions suggesting they represent a bona fide functional memory subset (91).

There are many possible explanations for the observed elevation in Tfh-like cells in autoimmune settings. In some cases, this may be secondary to generalized immune activation associated with disease. However, Tfh changes can be detected prior to the onset of overt disease in children at risk of T1D (92), and insulin-specific T cells are enriched for a CXCR5+ Tfh precursor population in children who have only recently developed islet autoantibodies (93). The blood Tfh signature is frequently linked to disease activity (76, 78), and successful treatment of SLE has been shown to decrease Tfh while numbers of Th1 and Th2 cells remain unaltered (94). Persistent antigen has been suggested to favor Tfh differentiation and maintenance (4, 95), so continuous availability of tissue antigen could potentially support this response in chronic autoimmune conditions.

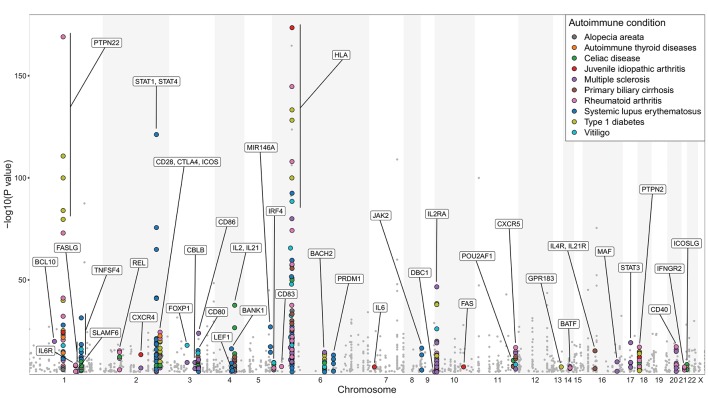

The strongest genetic association with autoimmunity maps to the HLA region (96), consistent with its role in presenting the TCR ligands that drive pathogenic and regulatory (97) T cell responses. Interestingly, other genes conferring susceptibility to autoimmunity in humans include many candidates associated with T cell/B cell collaboration. Accordingly, in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) from ten selected autoimmune conditions (T1D, RA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, autoimmune thyroid diseases, vitiligo, alopecia areata, SLE, MS, primary biliary cirrhosis, celiac disease), polymorphisms in several genes integral for T cell/B cell co-operation bear significant associations with disease susceptibility (Figure 2). These genes are highlighted on the basis of their relevance to T cell/B cell collaboration, however it should be noted that many are also likely to influence T cell interactions with other cell types, such as dendritic cells. A selection of these is discussed below.

Figure 2.

Genes involved in regulating T cell/B cell collaboration are associated with autoimmunity. Manhattan plot of GWAS analysis for 10 selected autoimmune diseases: alopecia areata, autoimmune thyroid diseases (Hashimoto's thyroiditis and Graves' disease), celiac disease, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, MS, primary biliary cirrhosis, RA, SLE, T1D, and vitiligo. Statistical strength of association (-Log10P) is plotted against genomic position. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes with known function in regulating T cell/B cell collaboration are marked with colored circles; other SNPs are marked with gray dots. More than 60% of the highlighted genes are implicated in more than one of the 10 selected autoimmune diseases. The NHGRI-EBI Catalog of published genome-wide association studies (98) was used to generate this figure (catalog version: gwas_catalog_v1.0.2-associations_e92_r2018-05-12; access date 17.05.2018). Only SNP traits with a p-value of <1.0 × 10−5 in the overall (initial GWAS + replication) population are included in this catalog. For clarity, the y-axis scale used in this figure excludes HLA-DRB1 SNP associations with -Log10P values of 299, 250 (x2), 185.4 in RA and 224.4, 206, 183 in MS, and an insulin SNP association with -Log10P of 185 in T1D. This figure only serves illustrative purposes and no direct comparisons should be made between associations taken from different studies.

Costimulatory molecules

The CD28, CTLA4, and ICOS genes are located within a 300 kb region on human chromosome 2 and likely arose from sequential gene duplication (99). Variation at this locus is associated with autoimmunity (100) and blockade of CD28 signaling with CTLA-4-Ig fusion protein is a recognized treatment strategy in a number of autoimmune disease settings (101). As mentioned above, autoimmunity in sanroque mice is associated with de-repression of ICOS mRNA, and dysregulated ICOS expression is also believed to underlie the increase in Tfh and autoimmune phenotype seen in the Sle1 lupus-prone mouse model (102). The genes encoding the ligands for these receptors, CD80, CD86, and ICOSLG, are also associated with autoimmunity (Figure 2), consistent with the need to tightly control the core pathways that control the induction of T cell help. CD40, which provides an essential pathway for GC B cells to perceive T cell help, is implicated in multiple autoimmune diseases (103) as is DBC1 which regulates its downstream signaling (104). OX40L contributes to pathology in a mouse model of SLE (34) and polymorphisms in OX40L (TNFSF4) are associated with several diseases where humoral immunity is known to be perturbed including SLE and RA, leading to the investigation of this pathway as a therapeutic target (105).

Cytokines

Cytokines are important regulators of the GC response, and many of the key cytokines implicated in shaping Tfh and GC B cell differentiation are associated with autoimmune susceptibility. IL2RA, which encodes the high affinity subunit for the IL-2-receptor shows one of the strongest associations with T1D outside of the HLA region (106), and as discussed above, IL-2 signaling potently inhibits Tfh differentiation. The IL2 and IL21 genes located next to each other on human chromosome 4 (107), and IL4RA and IL21RA on chromosome 16 (108) also bear a strong association with autoimmunity, potentially reflecting the key roles of IL-21 and IL-4 in orchestrating collaboration between Tfh and B cells within GC (109, 110). Also highlighted by GWAS are IL6, IL6R, and BANK1 which controls IL-6 secretion (111). While IL-12 is considered to be the major cytokine driving Tfh formation in humans (67, 68), this differentiation fate can also be promoted by IL-6. The demonstration that plasmablast-derived IL-6 can promote Tfh differentiation, in a manner that can be inhibited by treatment with the anti-IL-6R antibody tocilizumab (112), highlights a further positive feedback loop between Tfh and B cells.

Additional genes linked to T cell/B cell collaboration

Other autoimmune-susceptibility genes featured in Figure 2 include the protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPN22, which controls the number and activity of Tfh cells (113), and PTPN2, deficiency of which leads to increased Tfh cells, GC and autoimmune pathology (114). The chemokine receptors CXCR5 and CXCR4, which play integral roles in regulating cell distribution across GC and facilitating Tfh and GC B cell interactions, are also highlighted (19, 115). The GWAS data also highlight Gpr183, the gene encoding the 7α,25-dihydroxycholesterol receptor EBI-2, which must be downregulated for appropriate B cell positioning in GC (116, 117). Indeed forced expression of EBI-2 was shown to diminish the GC response and instead direct B cells to extrafollicular sites (117) while transduction of T cells with an EBI-2 expression vector impaired their capacity to localize to GC (118). Another gene product associated with autoimmunity in this dataset is SLAMF6, which co-operates with SAP to promote T cell/B cell adhesion and is essential for formation of functional GC (119). Importantly, in addition to surface molecules and soluble factors, the GWAS data also draw attention to a number of transcription factors associated with the GC response including BATF, IRF4, Maf, Bob1 (Pou2af1), Rel and Blimp-1 (Prdm1) (36, 120–125), further highlighting the link between T and B cell interactions and autoimmune susceptibility.

T cell/B cell collaboration outside secondary lymphoid tissues

Development of tertiary lymphoid structures is frequently seen in chronically inflamed tissues (126), and T cell/B cell collaboration at ectopic sites has been suggested to fuel ongoing autoimmunity (127). Recent findings suggest T cells providing B cell help outside secondary lymphoid organs may bear a distinct phenotype; accordingly Rao et al. described a PD-1hiCXCR5−CD4+ “peripheral helper” T cell population in the synovium of patients with RA which lacked Bcl6 but expressed IL-21, CXCL13, ICOS, and Maf (128). These cells actively promoted memory B cell differentiation into plasma cells in vitro and were located adjacent to B cells both inside and outside synovial lymphoid aggregates.

Similarly, in a murine model of airway inflammation, T cells interacting with B cells in the lung exhibited a CXCR5−Bcl6− phenotype despite possessing high B cell helper potential, likely via their expression of CD40L, IL-21, and IL-4 (129). Remarkably, around 40% of lung-infiltrating B cells in this model showed a GC phenotype implying effective T cell/B cell collaboration, even though the cells were present in loose aggregates rather than well-organized structures.

The relationship of peripheral helper T cells to Tfh cells is currently unclear. However, one study documenting CXCR5−BCL6−CXCL13+ T cells in rheumatoid synovial fluid postulated that these may derive from Tfh cells undergoing progressive differentiation, and loss of CXCR5 and Bcl6 in the synovium (130). The provenance of peripheral helper T cells remains an important question for future clarification.

Interrupting T cell/B cell collaboration by B cell depletion

Since autoimmunity may arise through over-exuberant T and B cell interactions leading to autoantibody production, depletion of the B cell population has been explored as a treatment strategy. Surprisingly, this has only a moderate effect on serum autoantibody levels, which does not correlate with efficacy, implying an alternative mechanism underlies the beneficial impact (131, 132). Given the interdependence of Tfh and B cell responses highlighted above, one possibility is that B cell depletion affects Tfh cells. Indeed, it has been shown in mice that deletion of GC B cells substantially impairs Tfh homeostasis (4, 133).

In human studies, Xu et al. reported a significant reduction in circulating Tfh frequencies and serum IL-21 levels following B cell depletion with rituximab in patients with T1D, emphasizing Tfh and B cell interdependence in this disease setting (134). Similarly, the elevation in circulating Tfh seen in individuals with Sjögren's syndrome was shown to be normalized by B cell depletion (135).

However, a study by Wallin et al. found no reduction in Tfh numbers in lymph nodes and blood from patients treated with rituximab prior to kidney transplantation (136). This finding may reflect “setting-dependent” roles for B cells in Tfh cell maintenance in humans. Of note, this study identified Tfh cells using CD57 expression which was initially reported to mark GC-resident functionally mature Tfh (137, 138), but was subsequently shown to be expressed by less than a third of GC-resident Tfh cells (139). Therefore, investigating the dynamics of CD57- Tfh cells may be of interest here.

More recently, B cell depletion with ocrelizumab, a humanized anti-CD20 antibody, has been shown to slow disease progression in patients with some forms of MS when compared to placebo or interferon beta-1a treatment (140, 141). Whether B cell depletion impacts Tfh homeostasis in this disease setting is currently unclear, however treatment has been associated with a decrease in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) T cells as well as B cells and a reduction in CSF levels of the chemokine CXCL13 (142) which can be produced by Tfh cells. Overall, effects on Tfh homeostasis may offer an additional explanation for the efficacy of B cell depletion in certain settings.

Conclusion

Cooperation between T cells and B cells has been fine-tuned by evolutionary pressures to optimize rapid immune defense. These interactions ensure successful long-term immunity, exemplified by the development of effective T cell and B cell memory. Given that chronic autoimmune diseases may be sustained by the perpetuation, rather than initiation, of self-directed immune responses, the bi-directional interaction between T and B cells may be key to this and may therefore constitute an important therapeutic target.

Author contributions

LP wrote and edited the manuscript and designed figures. NE designed figures and reviewed and edited the manuscript. VO, FH, ER, EN, and CW reviewed and edited the manuscript. LW conceptualized, wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The work of the authors is supported by the Medical Research Council, Diabetes UK and The Rosetrees Trust. The authors have received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 675395.

References

- 1.Crotty S. T follicular helper cell differentiation, function, and roles in disease. Immunity (2014) 41:529–42. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coffey F, Alabyev B, Manser T. Initial clonal expansion of germinal center B cells takes place at the perimeter of follicles. Immunity (2009) 30:599–609. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerfoot SM, Yaari G, Patel JR, Johnson KL, Gonzalez DG, Kleinstein SH, et al. Germinal center B cell and T follicular helper cell development initiates in the interfollicular zone. Immunity (2011) 34:947–60. 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumjohann D, Preite S, Reboldi A, Ronchi F, Ansel KMM, Lanzavecchia A, et al. Persistent antigen and germinal center B cells sustain T follicular helper cell responses and phenotype. Immunity (2013) 38:596–605. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deenick EK, Chan A, Ma CS, Gatto D, Schwartzberg PL, Brink R, et al. Follicular helper T cell differentiation requires continuous antigen presentation that is independent of unique B cell signaling. Immunity (2010) 33:241–53. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rolf J, Bell SE, Kovesdi D, Janas ML, Soond DR, Webb LMC, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity in T cells regulates the magnitude of the germinal center reaction. J Immunol. (2010) 185:4042–52. 10.4049/jimmunol.1001730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitmire JK, Asano MS, Kaech SM, Sarkar S, Hannum LG, Shlomchik MJ, et al. Requirement of B cells for generating CD4+ T cell memory. J Immunol. (2009) 182:1868–76. 10.4049/jimmunol.0802501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ise W, Inoue T, McLachlan JB, Kometani K, Kubo M, Okada T, et al. Memory B cells contribute to rapid Bcl6 expression by memory follicular helper T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2014) 111:1–6. 10.1073/pnas.1404671111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asrir A, Aloulou M, Gador M, Pérals C, Fazilleau N. Interconnected subsets of memory follicular helper T cells have different effector functions. Nat Commun. (2017) 8:847. 10.1038/s41467-017-00843-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fazilleau N, Eisenbraun MD, Malherbe L, Ebright JN, Pogue-Caley RR, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, et al. Lymphoid reservoirs of antigen-specific memory T helper cells. Nat Immunol. (2007) 8:753–61. 10.1038/ni1472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crotty S. A brief history of T cell help to B cells. Nat Rev Immunol. (2015) 15:185–9. 10.1038/nri3803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawabe T, Naka T, Yoshida K, Tanaka T, Fujiwara H, Suematsu S, et al. The immune responses in CD40-deficient mice: impaired immunoglobulin class switching and germinal center formation. Immunity (1994) 1:167–78. 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90095-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foy TM, Laman JD, Ledbetter JA, Aruffo A, Claassen E, Noelle RJ. gp39-CD40 interactions are essential for germinal center formation and the development of B cell memory. J Exp Med. (1994) 180:157–63. 10.1084/jem.180.1.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi Y, Dutta PR, Cerasoli DM, Kelsoe G. In situ studies of the primary immune response to (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl)acetyl. V. Affinity maturation develops in two stages of clonal selection. J Exp Med. (1998) 187:885–95. 10.1084/jem.187.6.885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen RC, Armitage RJ, Conley ME, Rosenblatt H, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, et al. CD40 ligand gene defects responsible for X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome. Science (1993) 259:990–3. 10.1126/science.7679801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker LSK, Gulbranson-Judge A, Flynn S, Brocker T, Raykundalia C, Goodall M, et al. Compromised OX40 function in CD28-deficient mice is linked with failure to develop CXC chemokine receptor 5-positive CD4 cells and germinal centers. J Exp Med. (1999) 190:1115–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferguson SE, Han S, Kelsoe C, Thompson CB. CD28 is required for germinal center formation. J Immunol. (1996) 156:4576–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borriello F, Sethna MP, Boyd SD, Schweitzer AN, Tivol EA, Jacoby D, et al. B7-1 and B7-2 have overlapping, critical roles in immunoglobulin class switching and germinal center formation. Immunity (1997) 6:303–13. 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80333-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haynes NM, Allen CDC, Lesley R, Ansel KM, Killeen N, Cyster JG. Role of CXCR5 and CCR7 in follicular Th cell positioning and appearance of a programmed cell death gene-1 high germinal center-associated subpopulation. J Immunol. (2007) 179:5099–108. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moriyama S, Takahashi N, Green JA, Hori S, Kubo M, Cyster JG, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 is critical for follicular helper T cell retention in germinal centers. J Exp Med. (2014) 211:1297–305. 10.1084/jem.20131666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang CJ, Heuts F, Ovcinnikovs V, Wardzinski L, Bowers C, Schmidt EM, et al. CTLA-4 controls follicular helper T-cell differentiation by regulating the strength of CD28 engagement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2015) 112:524–9. 10.1073/pnas.1414576112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker LSK, Sansom DM. Confusing signals: recent progress in CTLA-4 biology. Trends Immunol. (2015) 36:63–70. 10.1016/j.it.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker LSK, Sansom DM. The emerging role of CTLA4 as a cell-extrinsic regulator of T cell responses. Nat Rev Immunol. (2011) 11:852–63. 10.1038/nri3108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wing JB, Ise W, Kurosaki T, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells control antigen-specific expansion of Tfh cell number and humoral immune responses via the coreceptor CTLA-4. Immunity (2014) 41:1013–25. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sage PT, Paterson AM, Lovitch SB, Sharpe AH. The coinhibitory receptor CTLA-4 controls B cell responses by modulating T follicular helper, T follicular regulatory, and T regulatory cells. Immunity (2014) 41:1026–39. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linterman MA, Pierson W, Lee SK, Kallies A, Kawamoto S, Rayner TF, et al. Foxp3+ follicular regulatory T cells control the germinal center response. Nat Med. (2011) 17:975–82. 10.1038/nm.2425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wing JB, Tekgüç M, Sakaguchi S. Control of germinal center responses by T-follicular regulatory cells. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:1910 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fazilleau N, Aloulou M. Several follicular regulatory T cell subsets with distinct phenotype and function emerge during germinal center reactions. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:1792 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie MM, Dent AL. Unexpected help: follicular regulatory T cells in the germinal center. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:1536. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flynn S, Toellner K-M, Raykundalia C, Goodall M, Lane P. CD4 T cell cytokine differentiation: the B cell activation molecule, OX40 ligand, instructs CD4 T cells to express interleukin 4 and upregulates expression of the chemokine receptor, Blr-1. J Exp Med. (1998) 188:297–304. 10.1084/jem.188.2.297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brocker T, Gulbranson-Judge A, Flynn S, Riedinger M, Raykundalia C, Lane P. CD4 T cell traffic control: in vivo evidence that ligation of OX40 on CD4 T cells by OX40-ligand expressed on dendritic cells leads to the accumulation of CD4 T cells in B follicles. Eur J Immunol. (1999) 29:1610–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boettler T, Moeckel F, Cheng Y, Heeg M, Salek-Ardakani S, Crotty S, et al. OX40 facilitates control of a persistent virus infection. PLoS Pathog. (2012) 8:e1002913. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tahiliani V, Hutchinson TE, Abboud G, Croft M, Salek-Ardakani S. OX40 cooperates with ICOS to amplify follicular Th cell development and germinal center reactions during infection. J Immunol. (2017) 198:218–28. 10.4049/jimmunol.1601356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cortini A, Ellinghaus U, Malik TH, Cunninghame Graham DS, Botto M, Vyse TJ. B cell OX40L supports T follicular helper cell development and contributes to SLE pathogenesis. Ann Rheum Dis. (2017) 76:2095–103. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boettler T, Choi YS, Salek-Ardakani S, Cheng Y, Moeckel F, Croft M, et al. Exogenous OX40 stimulation during Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection impairs follicular Th cell differentiation and diverts CD4 T cells into the effector lineage by upregulating blimp-1. J Immunol. (2013) 191:5026–35. 10.4049/jimmunol.1300013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnston RJ, Poholek AC, DiToro D, Yusuf I, Eto D, Barnett B, et al. Bcl6 and Blimp-1 are reciprocal and antagonistic regulators of T follicular helper cell differentiation. Science (2009) 325:1006–10. 10.1126/science.1175870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marriott CL, Mackley EC, Ferreira C, Veldhoen M, Yagita H, Withers DR. OX40 controls effector CD4+ T-cell expansion, not follicular T helper cell generation in acute Listeria infection. Eur J Immunol. (2014) 44:2437–47. 10.1002/eji.201344211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akiba H, Takeda K, Kojima Y, Usui Y, Harada N, Yamazaki T, et al. The role of ICOS in the CXCR5+ follicular B helper T cell maintenance in vivo. J Immunol. (2005) 175:2340–8. 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McAdam AJ, Greenwald RJ, Levin MA, Chernova T, Malenkovich N, Ling V, et al. Icos is critical for CD40-mediated antibody class switching. Nature (2001) 409:102–5. 10.1038/35051107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tafuri A, Shahinian A, Bladt F, Yoshinaga SK, Jordana M, Wakeham A, et al. ICOS is essential for effective T-helper-cell responses. Nature (2001) 409:105–9. 10.1038/35051113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dong C, Juedes AE, Temann UA, Shresta S, Allison JP, Ruddle NH, et al. ICOS co-stimulatory receptor is essential for T-cell activation and function. Nature (2001) 409:97–101. 10.1038/35051100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dong C, Temann UA, Flavell RA. Cutting edge: critical role of inducible costimulator in germinal center reactions. J Immunol. (2001) 166:3659–62. 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi YS, Kageyama R, Eto D, Escobar TC, Johnston RJ, Monticelli L, et al. ICOS receptor instructs T follicular helper cell versus effector cell differentiation via induction of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6. Immunity (2011) 34:932–46. 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weber JP, Fuhrmann F, Feist RK, Lahmann A, Al Baz MS, Gentz L-J, et al. ICOS maintains the T follicular helper cell phenotype by down-regulating Krüppel-like factor 2. J Exp Med. (2015) 212:217–33. 10.1084/jem.20141432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gigoux M, Shang J, Pak Y, Xu M, Choe J, Mak TW, et al. Inducible costimulator promotes helper T-cell differentiation through phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2009) 106:20371–6. 10.1073/pnas.0911573106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walker LSK, Wiggett HE, Gaspal FMC, Raykundalia CR, Goodall MD, Toellner K-MM, et al. Established T cell-driven germinal center B cell proliferation is independent of CD28 signaling but is tightly regulated through CTLA-4. J Immunol. (2003) 170:91–8. 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Webb LMC, Linterman MA. Signals that drive T follicular helper cell formation. Immunology (2017) 152:185–94. 10.1111/imm.12778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Linterman MA, Denton AE, Divekar DP, Zvetkova I, Kane L, Ferreira C, et al. CD28 expression is required after T cell priming for helper T cell responses and protective immunity to infection. Elife (2014) 3:1–21. 10.7554/eLife.03180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mak TW, Shahinian A, Yoshinaga SK, Wakeham A, Boucher LM, Pintilie M, et al. Costimulation through the inducible costimulator ligand is essential for both T helper and B cell functions in T cell-dependent B cell responses. Nat Immunol. (2003) 4:765–72. 10.1038/ni947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Hwang D, Yang XO, Kang HS, Ma L, et al. Generation of T Follicular helper cells is mediated by interleukin-21 but independent of T helper 1, 2, or 17 cell lineages. Immunity (2008) 29:138–49. 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu H, Li X, Liu D, Li J, Zhang X, Chen X, et al. Follicular T-helper cell recruitment governed by bystander B cells and ICOS-driven motility. Nature (2013) 496:523–7. 10.1038/nature12058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bossaller L, Burger J, Draeger R, Grimbacher B, Knoth R, Plebani A, et al. ICOS Deficiency is associated with a severe reduction of CXCR5+CD4 germinal center Th cells. J Immunol. (2006) 177:4927–32. 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Warnatz K, Bossaller L, Salzer U, Skrabl-Baumgartner A, Schwinger W, Van Der Burg M, et al. Human ICOS deficiency abrogates the germinal center reaction and provides a monogenic model for common variable immunodeficiency. Blood (2006) 107:3045–52. 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allen CDC, Okada T, Tang HL, Cyster JG. Imaging of germinal center selection events during affinity maturation. Science (2007) 315:528–31. 10.1126/science.1136736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Okada T, Miller MJ, Parker I, Krummel MF, Neighbors M, Hartley SB, et al. Antigen-engaged B cells undergo chemotaxis toward the T zone and form motile conjugates with helper T cells. PLoS Biol. (2005) 3:e150. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qi H, Cannons JL, Klauschen F, Schwartzberg PL, Germain RN. SAP-controlled T-B cell interactions underlie germinal centre formation. Nature (2008) 455:764–9. 10.1038/nature07345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cannons JL, Qi H, Lu KT, Dutta M, Gomez-Rodriguez J, Cheng J, et al. Optimal germinal center responses require a multistage T cell:B cell adhesion process involving integrins, SLAM-associated protein, and CD84. Immunity (2010) 32:253–65. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Czar MJ, Kersh EN, Mijares LA, Lanier G, Lewis J, Yap G, et al. Altered lymphocyte responses and cytokine production in mice deficient in the X-linked lymphoproliferative disease gene SH2D1A/DSHP/SAP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2001) 98:7449–54. 10.1073/pnas.131193098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crotty S, Kersh EN, Cannons J, Schwartzberg PL, Ahmed R. SAP is required for generating long term humoral immunity. Nature (2003) 421:282–7. 10.1038/nature01318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cannons JL, Yu LJ, Jankovic D, Crotty S, Horai R, Kirby M, et al. SAP regulates T cell-mediated help for humoral immunity by a mechanism distinct from cytokine regulation. J Exp Med. (2006) 203:1551–65. 10.1084/jem.20052097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yusuf I, Kageyama R, Monticelli L, Johnston RJ, Ditoro D, Hansen K, et al. Germinal center T follicular helper cell IL-4 production is dependent on signaling lymphocytic activation molecule receptor (CD150). J Immunol. (2010) 185:190–202. 10.4049/jimmunol.0903505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cannons JL, Tangye SG, Schwartzberg PL. SLAM family receptors and SAP adaptors in immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. (2011) 29:665–705. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ballesteros-Tato A, León B, Graf BA, Moquin A, Adams PS, Lund FE, et al. Interleukin-2 inhibits germinal center formation by limiting T follicular helper cell differentiation. Immunity (2012) 36:847–56. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johnston RJ, Choi YS, Diamond JA, Yang JA, Crotty S. STAT5 is a potent negative regulator of T FH cell differentiation. J Exp Med. (2012) 209:243–50. 10.1084/jem.20111174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li J, Lu E, Yi T, Cyster JG. EBI2 augments Tfh cell fate by promoting interaction with IL-2-quenching dendritic cells. Nature (2016) 533:110–4. 10.1038/nature17947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Crotty S. Follicular Helper CD4 T Cells (T FH). Annu Rev Immunol. (2011) 29:621–63. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ma CS, Suryani S, Avery DT, Chan A, Nanan R, Santner-Nanan B, et al. Early commitment of nave human CD4+ T cells to the T follicular helper (FH) cell lineage is induced by IL-12. Immunol Cell Biol. (2009) 87:590–600. 10.1038/icb.2009.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schmitt N, Morita R, Bourdery L, Bentebibel SE, Zurawski SM, Banchereau J, et al. Human dendritic cells induce the differentiation of interleukin-21-producing T follicular helper-like cells through interleukin-12. Immunity (2009) 31:158–69. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shulman Z, Gitlin AD, Weinstein JS, Lainez B, Esplugues E, Flavell RA, et al. Dynamic signaling by T follicular helper cells during germinal center B cell selection. Science (2014) 345:1058–62. 10.1126/science.1257861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Linterman MA, Rigby RJ, Wong RK, Yu D, Brink R, Cannons JL, et al. Follicular helper T cells are required for systemic autoimmunity. J Exp Med. (2009) 206:561–76. 10.1084/jem.20081886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Silva DG, Daley SR, Hogan J, Lee SK, Teh CE, Hu DY, et al. Anti-islet autoantibodies trigger autoimmune diabetes in the presence of an increased frequency of islet-reactive CD4 T cells. Diabetes (2011) 60:2102–11. 10.2337/db10-1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kenefeck R, Wang CJ, Kapadi T, Wardzinski L, Attridge K, Clough LE, et al. Follicular helper T cell signature in type 1 diabetes. J Clin Invest. (2015) 125:292–303. 10.1172/JCI76238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chevalier N, Macia L, Tan JK, Mason LJ, Robert R, Thorburn AN, et al. The role of follicular helper T cell molecules and environmental influences in autoantibody production and progression to inflammatory arthritis in mice. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2016) 68:1026–38. 10.1002/art.39481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Teng F, Klinger CN, Felix KM, Bradley CP, Wu E, Tran NL, et al. Gut Microbiota Drive autoimmune arthritis by promoting differentiation and migration of peyer's patch T follicular helper cells. Immunity (2016) 44:875–88. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moschovakis GL, Bubke A, Friedrichsen M, Falk CS, Feederle R, Förster R. T cell specific Cxcr5 deficiency prevents rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:1–13. 10.1038/s41598-017-08935-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tangye SG, Ma CS, Brink R, Deenick EK. The good, the bad and the ugly — TFH cells in human health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. (2013) 13:412–26. 10.1038/nri3447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vinuesa CG, Linterman MA, Yu D, MacLennan ICM. Follicular helper T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. (2016) 34:335–68. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ueno H. T follicular helper cells in human autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. (2016) 43:24–31. 10.1016/j.coi.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shulman Z, Gitlin AD, Targ S, Jankovic M, Pasqual G, Nussenzweig MC, et al. T follicular helper cell dynamics in germinal centers. Science (2013) 341:673–7. 10.1126/science.1241680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lüthje K, Kallies A, Shimohakamada Y, Belz GT, Light A, Tarlinton DM, et al. The development and fate of follicular helper T cells defined by an IL-21 reporter mouse. Nat Immunol. (2012) 13:491–8. 10.1038/ni.2261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu X, Yan X, Zhong B, Nurieva RI, Wang A, Wang X, et al. Bcl6 expression specifies the T follicular helper cell program in vivo. J Exp Med. (2012) 209:1841–52, S1–24. 10.1084/jem.20120219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weber JP, Fuhrmann F, Hutloff A. T-follicular helper cells survive as long-term memory cells. Eur J Immunol. (2012) 42:1981–8. 10.1002/eji.201242540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Choi YS, Yang JA, Yusuf I, Johnston RJ, Greenbaum J, Peters B, et al. Bcl6 expressing follicular helper CD4 T cells are fate committed early and have the capacity to form memory. J Immunol. (2013) 190:4014–26. 10.4049/jimmunol.1202963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hale JS, Youngblood B, Latner DR, Mohammed AUR, Ye L, Akondy RS, et al. Distinct memory cd4+ t cells with commitment to t follicular helper- and t helper 1-cell lineages are generated after acute viral infection. Immunity (2013) 38:805–17. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kitano M, Moriyama S, Ando Y, Hikida M, Mori Y, Kurosaki T, et al. Bcl6 Protein expression shapes pre-germinal center B cell dynamics and follicular helper T cell heterogeneity. Immunity (2011) 34:961–72. 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Locci M, Havenar-Daughton C, Landais E, Wu J, Kroenke MA, Arlehamn CL, et al. Human circulating PD-1+CXCR3-CXCR5+ memory Tfh cells are highly functional and correlate with broadly neutralizing HIV antibody responses. Immunity (2013) 39:758–69. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Morita R, Schmitt N, Bentebibel SE, Ranganathan R, Bourdery L, Zurawski G, et al. Human blood CXCR5+CD4+T cells are counterparts of t follicular cells and contain specific subsets that differentially support antibody secretion. Immunity (2011) 34:108–21. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chevalier N, Jarrossay D, Ho E, Avery DT, Ma CS, Yu D, et al. CXCR5 expressing human central memory CD4 T cells and their relevance for humoral immune responses. J Immunol. (2011) 186:5556–68. 10.4049/jimmunol.1002828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.He J, Tsai LM, Leong YA, Hu X, Ma CS, Chevalier N, et al. Circulating precursor CCR7loPD-1hi CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells indicate Tfh cell activity and promote antibody responses upon antigen reexposure. Immunity (2013) 39:770–81. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Boswell KL, Paris R, Boritz E, Ambrozak D, Yamamoto T, Darko S, et al. Loss of circulating CD4 T cells with B cell helper function during chronic HIV infection. PLoS Pathog. (2014) 10:e1003853. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sage PT, Alvarez D, Godec J, Andrian UH von, Sharpe AH. Circulating T follicular regulatory and helper cells have memory-like properties. J Clin Invest. (2014) 124:5191–204. 10.1172/JCI76861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Viisanen T, Ihantola E-L, Näntö-Salonen K, Hyöty H, Nurminen N, Selvenius J, et al. Circulating CXCR5+PD-1+ICOS+ follicular T helper cells are increased close to the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in children with multiple autoantibodies. Diabetes (2017) 66:437–447. 10.2337/db16-0714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Serr I, Fürst RW, Ott VB, Scherm MG, Nikolaev A, Gökmen F, et al. miRNA92a targets KLF2 and the phosphatase PTEN signaling to promote human T follicular helper precursors in T1D islet autoimmunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2016) 113:E6659–68. 10.1073/pnas.1606646113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.He J, Zhang X, Wei Y, Sun X, Chen Y, Deng J, et al. Low-dose interleukin-2 treatment selectively modulates CD4+ T cell subsets in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Med. (2016) 22:991–3. 10.1038/nm.4148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fahey LM, Wilson EB, Elsaesser H, Fistonich CD, McGavern DB, Brooks DG. Viral persistence redirects CD4 T cell differentiation toward T follicular helper cells. J Exp Med. (2011) 208:987–99. 10.1084/jem.20101773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fernando MMA, Stevens CR, Walsh EC, De Jager PL, Goyette P, Plenge RM, et al. Defining the role of the MHC in autoimmunity: a review and pooled analysis. PLoS Genet (2008) 4:e1000024. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ooi JD, Petersen J, Tan yu H, Huynh M, Willett ZJ, Ramarathinam SH, et al. Dominant protection from HLA-linked autoimmunity by antigen-specific regulatory T cells. Nature (2017) 545:243–7. 10.1038/nature22329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.MacArthur J, Bowler E, Cerezo M, Gil L, Hall P, Hastings E, et al. The new NHGRI-EBI Catalog of published genome-wide association studies (GWAS Catalog). Nucleic Acids Res. (2017) 45:D896–901. 10.1093/nar/gkw1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gough SCL, Walker LSK, Sansom DM. CTLA4 gene polymorphism and autoimmunity. Immunol Rev. (2005) 204:102–15. 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00249.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ueda H, Howson JMM, Esposito L, Heward J, Snook H, Chamberlain G, et al. Association of the T-cell regulatory gene CTLA4 with susceptibility to autoimmune disease. Nature (2003) 423:506–11. 10.1038/nature01621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bluestone JA, St. Clair EW, Turka LA. CTLA4Ig: bridging the basic immunology with clinical application. Immunity (2006) 24:233–8. 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mittereder N, Kuta E, Bhat G, Dacosta K, Cheng LI, Herbst R, et al. Loss of immune tolerance is controlled by ICOS in Sle1 mice. J Immunol. (2016) 197:491–503. 10.4049/jimmunol.1502241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Peters AL, Stunz LL, Bishop GA. CD40 and autoimmunity: the dark side of a great activator. Semin Immunol. (2009) 21:293–300. 10.1016/j.smim.2009.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kong S, Thiruppathi M, Qiu Q, Lin Z, Dong H, Chini EN, et al. DBC1 is a suppressor of B cell activation by negatively regulating alternative NF-κB transcriptional activity. J Immunol. (2014) 193:5515–24. 10.4049/jimmunol.1401798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Webb GJ, Hirschfield GM, Lane PJL. OX40, OX40L and autoimmunity: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. (2016) 50:312–32. 10.1007/s12016-015-8498-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pociot F, Akolkar B, Concannon P, Erlich HA, Julier C, Morahan G, et al. Genetics of type 1 diabetes: what's next? Diabetes (2010) 59:1561–71. 10.2337/db10-0076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Parrish-Novak J, Dillon SR, Nelson A, Hammond A, Sprecher C, Gross JA, et al. Interleukin 21 and its receptor are involved in NK cell expansion and regulation of lymphocyte function. Nature (2000) 408:57–63. 10.1038/35040504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ozaki K, Kikly K, Michalovich D, Young PR, Leonard WJ. Cloning of a type I cytokine receptor most related to the IL-2 receptor beta chain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2000) 97:11439–44. 10.1073/pnas.200360997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Weinstein JS, Herman EI, Lainez B, Licona-Limón P, Esplugues E, Flavell R, et al. TFH cells progressively differentiate to regulate the germinal center response. Nat Immunol. (2016) 17:1197–205. 10.1038/ni.3554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chevrier S, Kratina T, Emslie D, Tarlinton DM, Corcoran LM. IL4 and IL21 cooperate to induce the high Bcl6 protein level required for germinal center formation. Immunol Cell Biol. (2017) 95:925–32. 10.1038/icb.2017.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wu Y-Y, Kumar R, Haque MS, Castillejo-Lopez C, Alarcon-Riquelme ME. BANK1 Controls CpG-Induced IL-6 Secretion via a p38 and MNK1/2/eIF4E translation initiation pathway. J Immunol. (2013) 191:6110–6. 10.4049/jimmunol.1301203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chavele K-M, Merry E, Ehrenstein MR. Cutting edge: circulating plasmablasts induce the differentiation of human T follicular helper cells via IL-6 production. J Immunol. (2015) 194:2482–5. 10.4049/jimmunol.1401190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Maine CJ, Marquardt K, Cheung J, Sherman LA. PTPN22 controls the germinal center by influencing the numbers and activity of T follicular helper cells. J Immunol (2014) 192:1415–24. 10.4049/jimmunol.1302418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wiede F, Sacirbegovic F, Leong YA, Yu D, Tiganis T. PTPN2-deficiency exacerbates T follicular helper cell and B cell responses and promotes the development of autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. (2016) 76:85–100. 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Allen CDCC, Ansel KM, Low C, Lesley R, Tamamura H, Fujii N, et al. Germinal center dark and light zone organization is mediated by CXCR4 and CXCR5. Nat Immunol. (2004) 5:943–52. 10.1038/ni1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Pereira J, Kelly L, Xu Y, Cyster J. EBV induced molecule-2 mediates B cell segregation between outer and center follicle. Nature (2009) 460:1122–6. 10.1038/nature08226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gatto D, Paus D, Basten A, Mackay CR, Brink R. Guidance of B cells by the orphan G protein-coupled receptor EBI2 shapes humoral immune responses. Immunity (2009) 31:259–69. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Suan D, Nguyen A, Moran I, Bourne K, Hermes JR, Arshi M, et al. T follicular helper cells have distinct modes of migration and molecular signatures in naive and memory immune responses. Immunity (2015) 42:704–18. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kageyama R, Cannons JL, Zhao F, Yusuf I, Lao C, Locci M, et al. The receptor Ly108 functions as a SAP adaptor-dependent on-off switch for T cell help to B cells and NKT cell development. Immunity (2012) 36:986–1002. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ise W, Kohyama M, Schraml BU, Zhang T, Schwer B, Basu U, et al. The transcription factor BATF controls the global regulators of class-switch recombination in both B cells and T cells. Nat Immunol. (2011) 12:536–43. 10.1038/ni.2037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bollig N, Brüstle A, Kellner K, Ackermann W, Abass E, Raifer H, et al. Transcription factor {IRF4} determines germinal center formation through follicular T-helper cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2012) 109:8664–9. 10.1073/pnas.1205834109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kroenke MA, Eto D, Locci M, Cho M, Davidson T, Haddad EK, et al. Bcl6 and Maf cooperate to instruct human follicular helper CD4 T cell differentiation. J Immunol. (2012) 188:3734–44. 10.4049/jimmunol.1103246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ochiai K, Maienschein-Cline M, Simonetti G, Chen J, Rosenthal R, Brink R, et al. Transcriptional regulation of germinal center B and plasma cell fates by dynamical control of IRF4. Immunity (2013) 38:918–29. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Stauss D, Brunner C, Berberich-Siebelt F, Höpken UE, Lipp M, Müller G. The transcriptional coactivator Bob1 promotes the development of follicular T helper cells via Bcl6. EMBO J. (2016) 35:881–98. 10.15252/embj.201591459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Chen G, Hardy K, Bunting K, Daley S, Ma L, Shannon MF. Regulation of the IL-21 gene by the NF- B transcription factor c-Rel. J Immunol. (2010) 185:2350–9. 10.4049/jimmunol.1000317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Neyt K, Perros F, GeurtsvanKessel CH, Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. Tertiary lymphoid organs in infection and autoimmunity. Trends Immunol. (2012) 33:297–305. 10.1016/j.it.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Corsiero E, Nerviani A, Bombardieri M, Pitzalis C. Ectopic lymphoid structures: powerhouse of autoimmunity. Front Immunol. (2016) 7:430. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Rao DA, Gurish MF, Marshall JL, Slowikowski K, Fonseka CY, Liu Y, et al. Pathologically expanded peripheral T helper cell subset drives B cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Nature (2017) 542:110–4. 10.1038/nature20810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Vu Van D, Beier KC, Pietzke LJ, Al Baz MS, Feist RK, Gurka S, et al. Local T/B cooperation in inflamed tissues is supported by T follicular helper-like cells. Nat Commun. (2016) 7:10875. 10.1038/ncomms10875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Manzo A, Vitolo B, Humby F, Caporali R, Jarrossay D, Dell'Accio F, et al. Mature antigen-experienced T helper cells synthesize and secrete the B cell chemoattractant CXCL13 in the inflammatory environment of the rheumatoid joint. Arthritis Rheum. (2008) 58:3377–87. 10.1002/art.23966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Fabris M, de Vita S, Blasone N, Visentini D, Pezzarini E, Pontarini E, et al. Serum levels of anti-CCP antibodies, anti-MCV antibodies and RF iga in the follow-up of patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with rituximab. Autoimmun Highlights (2010) 1:87–94. 10.1007/s13317-010-0013-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Cambridge G, Perry HC, Nogueira L, Serre G, Parsons HM, De La Torre I, et al. The effect of B-cell depletion therapy on serological evidence of B-cell and plasmablast activation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis over multiple cycles of rituximab treatment. J Autoimmun. (2014) 50:67–76. 10.1016/j.jaut.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Yusuf I, Stern J, McCaughtry TM, Gallagher S, Sun H, Gao C, et al. Germinal center B cell depletion diminishes CD4+ follicular T helper cells in autoimmune mice. PLoS ONE (2014) 9:e102791. 10.1371/journal.pone.0102791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Xu X, Shi Y, Cai Y, Zhang Q, Yang F, Chen H, et al. Inhibition of increased circulating Tfh cell by anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody in patients with type 1 diabetes. PLoS ONE (2013) 8:e79858. 10.1371/journal.pone.0079858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Verstappen GM, Kroese FGM, Meiners PM, Corneth OB, Huitema MG, Haacke EA, et al. B cell depletion therapy normalizes circulating follicular TH cells in primary Sjögren syndrome. J Rheumatol. (2017) 44:49–58. 10.3899/jrheum.160313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wallin EF, Jolly EC, Suchánek O, Bradley JA, Espéli M, Jayne DRW, et al. Human T-follicular helper and T-follicular regulatory cell maintenance is independent of germinal centers. Blood (2014) 124:2666–74. 10.1182/blood-2014-07-585976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kim CH, Rott LS, Clark-Lewis I, Campbell DJ, Wu L, Butcher EC. Subspecialization of CXCR5+ T cells: B helper activity is focused in a germinal center-localized subset of CXCR5+ T cells. J Exp Med. (2001) 193:1373–81. 10.1084/jem.193.12.1373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Rasheed A-U, Rahn H-P, Sallusto F, Lipp M, Müller G. Follicular B helper T cell activity is confined to CXCR5hiICOShi CD4 T cells and is independent of CD57 expression. Eur J Immunol. (2006) 36:1892–903. 10.1002/eji.200636136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Bentebibel S-E, Schmitt N, Banchereau J, Ueno H. Human tonsil B-cell lymphoma 6 (BCL6)-expressing CD4+ T-cell subset specialized for B-cell help outside germinal centers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2011) 108:E488–97. 10.1073/pnas.1100898108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Montalban X, Hauser SL, Kappos L, Arnold DL, Bar-Or A, Comi G, et al. Ocrelizumab versus placebo in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. (2017) 376:209–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Hauser SL, Bar-Or A, Comi G, Giovannoni G, Hartung H-P, Hemmer B, et al. Ocrelizumab versus interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. (2017) 376:221–34. 10.1056/NEJMoa1601277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Alvarez E, Piccio L, Mikesell RJ, Trinkaus K, Parks BJ, Naismith RT, et al. Predicting optimal response to B-cell depletion with rituximab in multiple sclerosis using CXCL13 index, magnetic resonance imaging and clinical measures. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. (2015) 1:205521731562380. 10.1177/2055217315623800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]