Abstract

A 19‐year‐old girl complained of an enlarged cervical mass. Based on clinical and cytological assessments, it was diagnosed as thyroid follicular carcinoma and left thyroidectomy was performed. Although thyroid neoplasms are rare in young people, differentiation is needed when the rapid growth of a goiter is detected.

Keywords: follicular carcinoma, juvenile goiter, thyroid neoplasm

1. INTRODUCTION

Thyroid carcinomas, especially thyroid follicular carcinoma, are rare in young people. Papillary carcinoma in the thyroid accounts for about 90% of thyroid carcinomas, and follicular carcinoma accounts for about 6% of thyroid carcinomas; the incidence of thyroid cancer in people in their twenties or younger is approximately 1 in 100 000 in Japan.1 Herein, we introduce a case of juvenile thyroid follicular carcinoma showing the rapid growth of a goiter.

2. CASE PRESENTATION

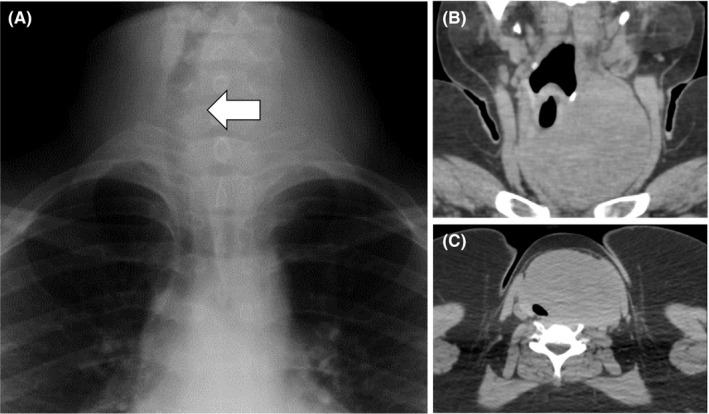

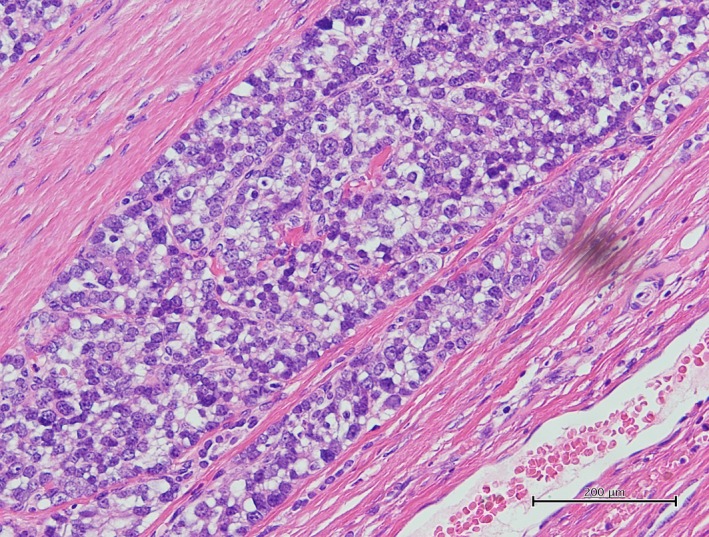

A 19‐year‐old girl who had a complaint of a swollen and enlarged feeling of her cervical mass for a few months visited our hospital (Figure 1). The patient had no particular past or family history including thyroidal disorders or other neoplasms. Cervical examination by ultrasonography revealed a diffusely enlarged left thyroid tumor showing a heterogenous pattern without clear capsule formation (Figure 2A), in which internal blood flow was augmented by a Doppler scan (Figure 2B). Endocrine examination showed that the patient was euthyroid and there were no thyroid autoantibodies (Table 1). A chest X‐ray showed a tracheal shift to the right and a dense shadow of the neck (Figure 3A). Computed tomography showed enlargement of the left thyroidal lesion and airway constriction (Figure 3B, coronal view; Figure 3C, horizontal view). Based on the results of cytology of a fine‐needle aspiration specimen, a follicular neoplasm was suspected. Left thyroidectomy was then performed, and a pathological diagnosis of follicular carcinoma (pT3N0M0 pStage I) was made on the basis of examination of the resected thyroid lesion (Figure 4). Cancer recurrence was not observed for a period of 1 year after surgery.

Figure 1.

Swollen cervical mass

Figure 2.

Ultrasonography revealed a diffusely enlarged left thyroid tumor (A). A Doppler scan showed augmented blood flow in the thyroid tumor (B)

Table 1.

Thyroid‐related laboratory data

| Normal range | ||

|---|---|---|

| TSH | 2.78 μU/mL | 0.33‐4.05 |

| FT4 | 0.91 ng/dL | 0.97‐1.69 |

| FT3 | 4.26 pg/mL | 2.30‐4.00 |

| Tg | 1533 ng/mL | 0.00‐33.70 |

| TgAb | Negative | <13.6 |

| TPOAb | Negative | <2.6 |

| CEA | 0.69 ng/mL | <5 |

| sIL‐2R | 391 U/mL | <391 |

Figure 3.

A chest X‐ray showed a tracheal shift to the right and a high‐density area in her neck (A, arrow). Computed tomography showed an enlarged thyroid tumor shifting the trachea to the right (B) and constricting the airway (C)

Figure 4.

Pathology of the resected thyroid tumor stained with hematoxylin and eosin showed proliferation of heteromorphic follicular carcinoma cells with capsular invasion

3. DISCUSSION

Thyroid follicular carcinoma is very rare in teenagers. In general, a simple goiter is seen in young females, and thyroid carcinomas tend to be found in middle‐aged to elderly women. In adults, nodule prevalence has been estimated to be 2%‐6% by palpation and 19%‐35% by ultrasound.2 Some studies using sonography showed that the prevalence of thyroid nodules in pediatrics is 0.2%‐5.1%.3 However, it has been estimated that 25% of thyroid nodules are malignant in children, while only 5% of them are malignant in adults.3 There has been no well‐documented report regarding the occurrence of follicular carcinoma in teenagers; however, in a 20‐year study on thyroid cancer in children and adolescents in China, 7 (8.4%) of 83 patients were reported to have follicular carcinoma.4

Childhood‐onset thyroid carcinoma is a more metastatic and aggressive local disease than thyroid carcinoma in adults.5 Therefore, management of thyroid nodules in children needs more attention than that in adults, and early detection is important. Nevertheless, children with thyroid carcinoma, especially those with follicular carcinoma, have a relatively good prognosis even if they have neck or distant metastasis.6 In addition, the general development and thyroid function of children born from mothers with childhood‐onset thyroid carcinoma do not seem to be affected by their former diseases.7

Not only thyroidectomy but also radioiodine ablation can be chosen as treatment for childhood‐onset thyroid carcinoma. Although radioiodine therapy is effective even for inoperable cases and adjuvant radioiodine therapy has been reported to reduce the risk of locoregional and distant recurrence,8 other cancer risk is increased by radioiodine therapy, particularly in the salivary gland, rectum, and colon; the risk of cancer in soft tissue and bone, leukemia, and pulmonary fibrosis might also be increased.9 Therefore, the balance of benefits and risks should be carefully considered. Pediatric follicular carcinoma has a lower frequency of metastasis and a lower grade of malignancy than those of papillary carcinoma.10

Considering this rare case, cervical lesions in children should be carefully followed up, and when growing potential is detected in young cases, thyroidal neoplasms should be readily differentiated by clinical and cytological assessments.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have stated explicitly that there are no conflicts of interest in connection with this article.

Oka K, Shien T, Otsuka F. Thyroid follicular carcinoma in a teenager: A case report. J Gen Fam Med. 2018;19:170–172. 10.1002/jgf2.185

REFERENCES

- 1. Matsuda A, Matsuda T, Shibata A, et al. Cancer incidence and incidence rates in Japan in 2007: a study of 21 population‐based cancer registries for the Monitoring of Cancer Incidence in Japan (MCIJ) project. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2013;43:328–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dean DS, Gharib H. Epidemiology of thyroid nodules. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;22:901–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Corrias A, Mussa A. Thyroid nodules in pediatrics: which ones can be left alone, which ones must be investigated, when and how. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2013;5(Suppl 1):57–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mao XC, Yu WQ, Shang JB, Wang KJ. Clinical characteristics and treatment of thyroid cancer in children and adolescents: a retrospective analysis of 83 patients. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2017;18:430–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ho WL, Zacharin MR. Thyroid carcinoma in children, adolescents and adults, both spontaneous and after childhood radiation exposure. Eur J Pediatr. 2016;175:677–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kowalski LP, Gonçalves Filho J, Pinto CA, Carvalho AL, de Camargo B. Long‐term survival rates in young patients with thyroid carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:746–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Balázs G, Lukács G, Juhász F, Györy F, Oláh E, Balogh E. Special features of childhood and juvenile thyroid carcinomas. Surg Today. 1996;26:536–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sawka AM, Thephamongkhol K, Brouwers M, Thabane L, Browman G, Gerstein HC. A systematic review and metaanalysis of the effectiveness of radioactive iodine remnant ablation for well‐differentiated thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3668–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jarzab B, Handkiewicz‐Junak D, Wloch J. Juvenile differentiated thyroid carcinoma and the role of radioiodine in its treatment: a qualitative review. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12:773–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Farahati J, Bucsky P, Parlowsky T, Mäder U, Reiners C. Characteristics of differentiated thyroid carcinoma in children and adolescents with respect to age, gender, and histology. Cancer. 1997;80:2156–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]