Abstract

The kidneys are the most vulnerable genitourinary organ in trauma, as they are involved in up to 3.25% of trauma patients. The most common mechanism for renal injury is blunt trauma (predominantly by motor vehicle accidents and falls), while penetrating trauma (mainly caused by firearms and stab wound) comprise the rest. High-velocity weapons impose specifically problematic damage because of the high energy and collateral effect. The mainstay of renal trauma diagnosis is based on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT), which is indicated in all stable patients with gross hematuria and in patients presenting with microscopic hematuria and hypotension. Additionally, CT should be performed when the mechanism of injury or physical examination findings are suggestive of renal injury (e.g. rapid deceleration, rib fractures, flank ecchymosis, and every penetrating injury of the abdomen, flank or lower chest). Renal trauma management has evolved during the last decades, with a distinct evolution toward a nonoperative approach. The lion’s share of renal trauma patients are managed nonoperatively with careful monitoring, reimaging when there is any deterioration, and the use of minimally invasive procedures. These procedures include angioembolization in cases of active bleeding and endourological stenting in cases of urine extravasation.

Keywords: hematuria, kidney injury, multiple trauma, renal injury

Background

Renal trauma management has evolved during the last decades, with a clear transition toward a nonoperative approach.1–4 This transition is probably derived from a combination of several aspects. First, the accumulative knowledge about the safety and outcome of the renal trauma nonoperative approach,1–17 and also for the management of other internal organs like the spleen and liver.18–21 Second, the improvement in imaging modalities [mainly computed tomography (CT) scanning]22 and in minimally invasive treatment techniques. These techniques include angioembolization in cases of active bleeding,23–25 and endourological stenting in cases of urine extravasation.22,26,27 The purpose of this review is to present the current best practice management of renal trauma.

Epidemiology, etiology and pathophysiology

Epidemiology

Despite its relatively protected retroperitoneal position, the kidney is the most commonly injured organ of the genitourinary system during trauma.28 Renal trauma can be an isolated injury but in 80–95% of cases there are concomitant injuries.16,29,30 Renal trauma affects predominantly men, 72–93% of cases,3,5,31,32 and it is more frequent in the young population with a mean age range from 31 to 38 years.5,16,17 The mean age is even younger when only penetrating trauma is included (27–28 years).6,30

The prevalence of renal trauma among trauma patients ranges from 0.3% to 3.25%,12,17,33–36 and the most common mechanism for renal injury is blunt trauma. Blunt renal trauma accounts for 71–95% of renal trauma cases.5,12,23,26,32–35

Etiology and pathophysiology of blunt renal trauma

In a systematic review conducted by Voelzke and Leddy, blunt renal trauma in the adult population was caused primarily by motor vehicle accidents (MVAs) (63%), followed by falls (43%), sports (11%) and pedestrian accidents (4%), while blunt trauma in the pediatric population was caused by more falls (27%) and pedestrian accidents (13%) and fewer MVAs (30%).31 In another review of the pediatric trauma registry, McAleer and colleagues found that pediatric renal blunt trauma was caused by bicycling (28%), falls (23%), all-terrain vehicle riding (8%), playground (8%), motorcycling (6%), team sports (6%), rollerblading (6%), playing ball (4%), equestrian sports (3%) and trampoline jumping (1%); no kidneys were lost in this study.37

The pathophysiology of blunt renal trauma is not completely understood but it seems that the major elements that cause the trauma are deceleration and acceleration forces. The kidney is covered by fat and the Gerota facia in the retroperitoneum, and the renal pedicle and uretero-pelvic junction (UPJ) are the major attachment elements; therefore, deceleration forces on these elements may cause renal injury like rupture or thrombosis.38 Acceleration forces may cause collision of the kidney in its surrounding elements, like the ribs and spine, and cause parenchymal and vascular injury.38

Abnormal kidneys that were found in 7% of the patients with blunt renal trauma are frequently injured by low-velocity impacts; nevertheless, contrast studies should be generously indicated, since the management of abnormal kidneys unmasked by trauma is largely dependent on the type of pathology.39 Schmidlin and colleagues found that pre-existing kidney abnormalities included hydronephrosis (38%), cysts (17%), tumor (7%), ectopic kidney (7%) and others (31%).39 According to a computer-simulated model, a liquid-filled incompressible compartment appears to amplify the force of the trauma impact, and therefore may explain the higher vulnerability of an abnormal kidney with hydronephrosis or a cyst.40

Etiology and pathophysiology of penetrating renal trauma

Most penetrating renal traumas, which are more severe and less predictable than blunt traumas, are caused by firearms (83–86%) and stab wound (14–17%).6,30 In combat scenarios, various kind of fragments [e.g. improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and other shrapnel] also cause penetrating renal trauma. Penetrating trauma is classified according to the velocity of the projectile: high-velocity projectiles (e.g. rifles), medium velocity (e.g. handguns) and low velocity (e.g. knife stab).

High-velocity weapons inflict greater damage because the bullets transmit large amounts of energy to the tissues. They form a temporary expansive cavitation that immediately collapses and creates shear forces and destruction in a much larger area then the projectile tract itself. Cavity formation disrupts tissue, ruptures blood vessels and nerves, and may fracture bones away from the path of the missile. In lower velocity injuries, the damage is usually confined to the track of the projectile.

The position of a stab wound affects its management. A stab wound to the anterior abdomen may injure vital renal structures like the renal pelvis and the vascular pedicle, while a stab wound posterior to the anterior axillary line will injure the parenchyma but less likely the vital renal parts.41

Classification and injury severity

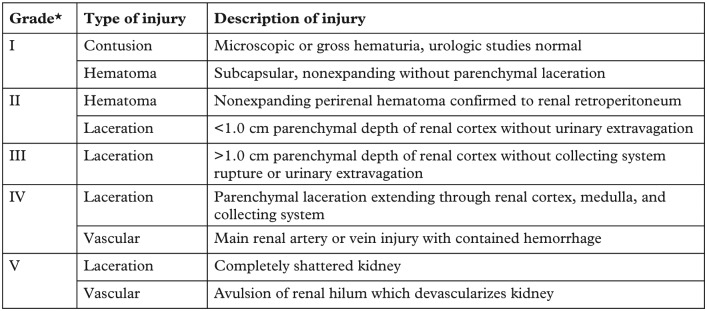

The most common renal trauma classification is the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) classification (Figure 1), an anatomic description, scaled from 1 to 5, representing the least to the most severe injury.42

Figure 1.

Renal trauma classification by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST).42

*Advance one grade for bilateral injuries up to grade III.

The AAST classification was validated by five studies.29,36,43–45 The AAST grade of renal injury, the overall injury severity of the patient, and the requirement of blood transfusion were the primary factors in determining the patient’s need for nephrectomy36,45 and overall outcome.36,43 The AAST grade is a predictor for morbidity in blunt and penetrating renal injury, and for mortality in blunt injury.44 The AAST grade has a statistically significant correlation with the need for surgery (from 0 to 93%) and for the risk for nephrectomy (0–86%).29 Moreover, patients with gunshot injury have higher AAST grades than those with blunt trauma.45

A substratification was proposed by Dugi and colleagues in 2010.46 They divided grade 4 into 4a (low risk) and 4b (high risk) according to three CT findings that were associated with the need for urgent intervention: perirenal hematoma rim distance larger than 3.5 cm, intravascular contrast extravasation, and medial renal laceration. They found that patients with zero to one risk factors (4a) were at low risk for intervention (7.1%), while those with two to three risk factors (4b) were at remarkably higher risk 66.7%.46 Another revision was proposed by Buckley and colleagues in 2011.47 According to the proposed definition, grade 4 injury includes all collecting system, renal pelvis, and segmental arterial/venous injuries. Grade 5 in this stratification is limited to major vascular injuries.

Injury severity distribution according to the AAST classification (based on two national trauma registry studies5,17 and a systematic review31): grade I, 22–28%; grade II, 28–30%; grade III, 20–26%; grade IV, 15–19%; grade V, 6–7%.

Initial evaluation: patient history, physical examination and laboratory tests

Initial assessment of every trauma patient that arrives in the emergency department includes a primary survey to evaluate airway, breathing and circulation, and taking vital signs, that is, heart rate, blood pressure, and blood oxygen saturation.

Patient history

Patient history and details of the event that caused the injury may not be available in a hemodynamically unstable patient, but when the patient is stable these data are very relevant for making the right treatment decisions. Understanding the injury mechanism and the forces involved is important because in cases of high deceleration or acceleration forces there is a high risk of renal injury, and further imaging should be done.38 The patient’s medical history is relevant as well. Pre-existing kidney abnormalities put the patient at specific risk, even from low-velocity impacts, and therefore further imaging studies should be generously indicated. The management of abnormal kidneys unmasked by trauma is largely dependent on the type of pathology.39,40 In cases of a solitary kidney or a solitary functioning kidney, a nephrectomy should be avoided unless it is crucial.

Physical examination

Physical examination helps to determine the location, extent and the severity of the injury. Blunt trauma to the flank, back, lower thorax and upper abdomen may harm the kidney. The physician should look for penetrating entry and exit wounds, abdominal peritoneal signs (e.g. guarding sign, rebound tenderness), and signs that may indicate renal trauma, such as visible hematuria, flank/upper abdomen hematoma, palpable mass, ecchymosis or abrasions, and rib fractures.48–50

Laboratory tests

Urine analysis, hematocrit and creatinine levels are necessary tests in order to diagnose microscopic hematuria, current blood loss status and baseline renal function,51 respectively. When active bleeding is suspected, blood type cross and match is mandatory. Additional laboratory evaluation should include complete blood count, blood gases and complete chemistry, including glucose, electrolytes, liver function tests, amylase and lipase to evaluate for other possible abdominal organ injury.

Hematuria, visible or nonvisible, is a very common sign of renal trauma. Nonvisible, also known as microscopic hematuria, is defined as three or more red blood cells (RBCs)/high power field (HPF) for adults52 and over 50 RBCs/HPF for pediatric patients.53 Visible hematuria is only present in 35–77% of renal trauma cases.10,45,54 Almost half of the patients with grade II renal trauma and 30% of the patients with grade IV renal trauma have no hematuria at presentation.45 Visible hematuria is even less common in penetrating renal injuries.30 Therefore, there is no absolute relationship between the type or degree of hematuria and the type and severity of the injured kidney.

Imaging

Computed tomography

Intravenous contrast-medium enhanced computed tomography (CT) is currently the gold standard imaging method for hemodynamically stable patients with blunt and penetrating renal trauma.1,48,55,56 It is widely available and it can quickly and accurately locate renal and other organ injuries by the anatomic and functional information that is essential for accurate staging.57 Concern regarding the toxicity of the contrast medium has not been confirmed, since low rates of contrast-induced nephropathy are seen in trauma patients.58 CT for renal trauma should include four phases: precontrast, postcontrast arterial (35 s post intravenous injection), postcontrast nephrogenic/portal venous (75 s post intravenous injection) and delayed (5–10 min post intravenous injection).22,57 The precontrast phase can identify renal calculi, which affect management,39,40 active bleeding or intraparenchymal hematoma.57 Postcontrast phases identify parenchymal and vascular damage, including the presence of active extravasation of contrast, other solid organ damage (e.g. liver and pancreas) and physiological variants that may affect management.57 The delayed phase can visualize the collecting system and possible ureteric injury.22 If the delayed phase cannot be performed during initial assessment due to urgent priorities, it should be completed whenever possible.

Intravenous pyelography

Intravenous pyelography (IVP) has been replaced by contrast-enhanced CT, except as an intraoperative tool to confirm the presence of a contralateral functioning kidney in a hemodynamically unstable patient, who could not complete preoperative CT. The use of intraoperative IVP includes a one-shot bolus injection of contrast media (2 mg/kg), followed by a single plain film taken after 10 min.59

Ultrasound

Ultrasound (US) is used to define free fluid in the setting of trauma, but it is inferior to CT in its resolution and the ability to accurately describe renal injury.60,61 In well trained and experienced hands, renal lacerations and hematomas can be reliably identified and delineated.62 However, US examination is unable to distinguish fresh blood from extravasated urine, and cannot identify vascular pedicle injuries and segmental infarct.60 US can be used for follow up of hydronephrosis, renal laceration managed nonoperatively and postoperative fluid collection.48 The absence of radiation, which is one of the main advantages of US, is very relevant for pediatric patients.

Indication for initial imaging

The goal of initial imaging is to grade the renal injury, demonstrate contralateral kidney and pre-existing renal abnormalities, and identify injuries to other organs. The decision to obtain an initial image is based on clinical aspects and the mechanism of injury. According to the European Association of Urology (EAU)63 and the American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines,55 CT should be performed in all hemodynamically stable blunt trauma patients with either gross hematuria or patients presenting with microscopic hematuria and hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg) at presentation. It should be clear that hemodynamic instability does not allow the diagnostic use of a CT. Moreover, CT should be performed when the mechanism of injury or the physical examination findings are suggestive of renal injury (i.e. rapid deceleration, a rib fracture, substantial flank ecchymosis, and every penetrating injury of the abdomen, flank or lower chest).

Indication for reimaging

The goal of reimaging is to diagnose possible complications and to evaluate clinical deterioration. Current guidelines recommend reimaging for patients with high-grade injuries after 2–4 days.48,55,63 Reimaging is also indicated for patients with clinical signs of complications, such as fever, worsening flank pain, ongoing blood loss and abdominal distension.48,55,63

Renal trauma management

The priorities of renal trauma management are (on descending order) avoiding mortality by bleeding control, nephron sparing and avoiding complications. In the past, the common practice to achieve these goals was to operate. Clinicians assumed that the best way to control bleeding is by surgery and the highest chance to avoid nephrectomy is by surgery where you can reconstruct vascular, UPJ or parenchymal injury as needed. In the last decades, real trauma management has evolved with a constant transition toward a nonoperative approach with nonoperative management (NOM) when needed, due to accumulative knowledge of the safety and better outcome of this approach.2–5,31 This approach includes both pediatric and adult populations.

Current indications for renal intervention

Absolute indications

According to current guidelines,55,63 absolute indications for renal intervention are hemodynamic instability and unresponsiveness to aggressive resuscitation due to renal hemorrhage, grade 5 vascular injury and an expanding or pulsatile perirenal hematoma found during laparotomy performed for associated injuries.

Relative indications

The renal trauma subcommittee summarized relative indications for renal exploration.48 They include a large laceration of the renal pelvis, avulsion of the UPJ, coexisting bowel or pancreatic injuries, persistent urinary leakage, and postinjury urinoma or perinephric abscess with failed percutaneous or endoscopic management. Additional indications are abnormal intraoperative one-shot IVP, devitalized parenchymal segment with associated urine leak, complete renal artery thrombosis of both kidneys or of a solitary kidney, and renal vascular injuries after failed angiographic management.

Nonoperative management

NOM includes observation with supportive care, bed rest with vital signs and laboratory test monitoring and reimaging when there is any deterioration), with the use of minimally invasive procedures (angioembolization or ureteral stenting) if indicated.

In two large-scale cohorts, renal trauma was managed nonoperatively in 84–95% of cases, with 2.7–5.4% of NOM failure.5,31 The effectiveness of NOM is supported by a systematic review and meta-analysis64 and by a smaller prospective study,11 and was found to be effective in treating complications of primary treatment as well.15

Nonoperative management for patients with blunt renal trauma

Grade I–II Patients with grade I and II renal trauma should be treated with NOM. In several studies, there was no need for a nephrectomy in any patient and rare indications for renal exploration.45,47,65

Grade III In two studies with grade III blunt renal trauma patients the reconstruction rate was 73% (87/119) and 11% (9/82) and the nephrectomy rate was 3.3% (4/119) and 4.8% (4/82), respectively.45,65 The nephrectomy rate was very low (1.8%) in another study (3/171).66 Aragona and colleagues found that among 21 patients with grade III blunt renal trauma the nephrectomy rate was 9% but when it was divided into two periods (2001–5, 2006–10) it was found that during the second period there were no nephrectomies. This is attributed to the growing use of angioembolization.54 Angioembolization has a success rate of 89% for the first time and 82% when repeated,67 and its effectiveness has been proven in treating patients with even higher grade renal trauma (IV/V).9,14,23,24,67 Therefore, patients with grade III renal trauma can be treated with NOM, by active monitoring and use of angioembolization if indicated.

Grade IV–V Most grade IV blunt renal injuries are treated nonoperatively, with a low incidence of nephrectomy.7,68 As mentioned before, there is a trend toward NOM for patients with grade IV blunt trauma with better outcome,54 which is attributed to the use of angioembolization. Lanchon and colleagues presented their first-line NOM protocol in 149 patients with grade IV or V renal blunt trauma. NOM was successful in 82% of the patients, with higher success in patients with grade IV (89% versus 52%) and the predictors for NOM failure were higher grade and hemodynamic instability. Eighteen percent underwent angioembolization, 17% underwent ureteral stent insertion, and 18% required delayed surgery.9 McGuire and colleagues used a similar protocol in 117 patients with grade III–V renal trauma. A total of 83% were treated with NOM and 9.3% (9/97) needed intervention: angioembolization in eight cases and only one case of nephrectomy. Predictors for intervention were grade V [relative risk (RR) 4.4] and use of platelets (RR 8.9). Van der Wilden and colleagues found that 77% (154/201) of patients with grade IV or V blunt renal trauma had successful NOM with no loss of kidney units. Age over 55 years and MVAs were the only two predictors for NOM failure.16 Angioembolization was successful in all nine patients with grade V blunt renal trauma in another study.24

According to these data, patients with grade IV–V blunt renal trauma who are hemodynamically stable should have the opportunity for NOM with active surveillance.55

Nonoperative management for patients with penetrating renal trauma

In the past, penetrating renal trauma was an absolute indication for renal exploration. Currently there is increasing evidence that supports NOM for hemodynamically stable patients with penetrating renal trauma.2,4,18,19,21 Penetrating renal trauma has a higher nephrectomy rate per grade injury,29 a higher rate of multiorgan injuries30 and a higher failure rate of angioembolization compared with blunt renal trauma.23 Nevertheless, most penetrating injuries can be treated nonoperatively.69 Moolman and colleagues found that 63% (47/64) were treated with NOM, none of them needed surgery.10

Operative management

Despite the obvious benefits of NOM, there are several situations in which surgery is the best option. Bjurlin and colleagues found that among 19,572 patients with renal trauma, 16.6% were managed surgically.5 Most clinicians would operate in hemodynamically unstable patients who do not respond to resuscitation.59 The most common approach is transperitoneal,70 with isolation of the renal artery and renal vein before renal exploration as a safety maneuver.71 This approach was found to reduce the nephrectomy rate from 56% to 18%.72 Vessel isolation was well described by Santucci and McAninch.29 Optimal control of the renal vessels enables the surgeon to avoid unnecessary nephrectomy by a thorough evaluation of the retroperitoneal area, although Gonzalez and colleagues found that vascular control of the renal hilum before opening Gerota’s fascia has no impact on the nephrectomy rate, transfusion requirements or blood loss.73 A stable hematoma should not be opened while a central or expanding hematoma, which indicates injuries of major vessels (renal vessels, aorta, vena cava), should be surgically explored.48

Renal salvage by renorrhaphy or partial nephrectomy requires maximal exposure of the kidney, debridement of nonviable tissue, control of bleeding by sutures, watertight closure of the collecting system and closure of parenchymal injuries. The omental flap of perirenal fat can be used for coverage of large defects.48 In all cases, drainage of the ipsilateral retroperitoneum is recommended for at least 48 h.29 In cases of suspected pancreatic injury, a second, pancreatic drainage should be placed to prevent abscess or fistula formation.74

Complications

Early complications include bleeding, infection, perinephric abscess, sepsis, urinary fistula, hypertension, urinary extravasation and urinoma. Delayed complications include bleeding, hydronephrosis, calculus formation, chronic pyelonephritis, hypertension, arteriovenous fistula, hydronephrosis and pseudo aneurysms. Most of the complications can be treated nonoperatively, percutaneously and endourologically. Renal trauma is a rare cause of hypertension and is estimated to be less than 5%.75 Persistent urinary extravasation from an otherwise viable kidney after blunt trauma often responds to stent placement or percutaneous drainage as necessary.76

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ORCID iD: Noam D. Kitrey  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5587-1485

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5587-1485

Contributor Information

Tomer Erlich, Department of Urology, The Chaim Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer, Israel.

Noam D. Kitrey, Department of Urology, The Chaim Sheba Medical Center, 2 Sheba Road, Tel Hashomer, 5262100, Israel.

References

- 1. Serafetinides E, Kitrey ND, Djakovic N, et al. Review of the current management of upper urinary tract injuries by the EAU Trauma Guidelines Panel. Eur Urol 2015; 67: 930–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Santucci RA, Fisher MB. The literature increasingly supports expectant (conservative) management of renal trauma–a systematic review. J Trauma 2005; 59: 493–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McCombie SP, Thyer I, Corcoran NM, et al. The conservative management of renal trauma: a literature review and practical clinical guideline from Australia and New Zealand. BJU Int 2014; 114(Suppl. 1): 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Broghammer JA, Fisher MB, Santucci RA. Conservative management of renal trauma: a review. Urology 2007; 70: 623–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bjurlin MA, Fantus RJ, Villines D. Comparison of nonoperative and surgical management of renal trauma: can we predict when nonoperative management fails? J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2017; 82: 356–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bjurlin MA, Jeng EI, Goble SM, et al. Comparison of nonoperative management with renorrhaphy and nephrectomy in penetrating renal injuries. J Trauma 2011; 71: 554–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Buckley JC, McAninch JW. Selective management of isolated and nonisolated grade IV renal injuries. J Urol 2006; 176: 2498–2502; discussion 2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jansen JO, Inaba K, Resnick S, et al. Selective non-operative management of abdominal gunshot wounds: survey of practise. Injury 2013; 44: 639–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lanchon C, Fiard G, Arnoux V, et al. High grade blunt renal trauma: predictors of surgery and long-term outcomes of conservative management. A prospective single center study. J Urol 2016; 195: 106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moolman C, Navsaria PH, Lazarus J, et al. Nonoperative management of penetrating kidney injuries: a prospective audit. J Urol 2012; 188: 169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Toutouzas KG, Karaiskakis M, Kaminski A, et al. Nonoperative management of blunt renal trauma: a prospective study. Am Surg 2002; 68: 1097–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wessells H, Suh D, Porter JR, et al. Renal injury and operative management in the United States: results of a population-based study. J Trauma 2003; 54: 423–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Altman AL, Haas C, Dinchman KH, et al. Selective nonoperative management of blunt grade 5 renal injury. J Urol 2000; 164: 27–30; discussion 30–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McGuire J, Bultitude MF, Davis P, et al. Predictors of outcome for blunt high grade renal injury treated with conservative intent. J Urol 2011; 185: 187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moudouni SM, Hadj Slimen M, Manunta A, et al. Management of major blunt renal lacerations: is a nonoperative approach indicated? Eur Urol 2001; 40: 409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van der Wilden GM, Velmahos GC, Joseph DK, et al. Successful nonoperative management of the most severe blunt renal injuries: a multicenter study of the research consortium of New England Centers for Trauma. JAMA Surg 2013; 148: 924–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McClung CD, Hotaling JM, Wang J, et al. Contemporary trends in the immediate surgical management of renal trauma using a national database. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013; 75: 602–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goin G, Massalou D, Bege T, et al. Feasibility of selective non-operative management for penetrating abdominal trauma in France. J Visc Surg 2016; 154: 167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lamb CM, Garner JP. Selective non-operative management of civilian gunshot wounds to the abdomen: a systematic review of the evidence. Injury 2014; 45: 659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Coccolini F, Catena F, Moore EE, et al. WSES classification and guidelines for liver trauma. World J Emerg Surg 2016; 11: 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Oyo-Ita A, Chinnock P, Ikpeme IA. Surgical versus non-surgical management of abdominal injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015: CD007383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fischer W, Wanaselja A, Steenburg SD. JOURNAL CLUB: incidence of urinary leak and diagnostic yield of excretory phase CT in the setting of renal trauma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015; 204: 1168–1172; quiz 1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hotaling JM, Sorensen MD, Smith TG, 3rd, et al. Analysis of diagnostic angiography and angioembolization in the acute management of renal trauma using a national data set. J Urol 2011; 185: 1316–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brewer ME, Jr, Strnad BT, Daley BJ, et al. Percutaneous embolization for the management of grade 5 renal trauma in hemodynamically unstable patients: initial experience. J Urol 2009; 181: 1737–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miller DC, Forauer A, Faerber GJ. Successful angioembolization of renal artery pseudoaneurysms after blunt abdominal trauma. Urology 2002; 59: 444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alsikafi NF, McAninch JW, Elliott SP, et al. Nonoperative management outcomes of isolated urinary extravasation following renal lacerations due to external trauma. J Urol 2006; 176: 2494–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Haas CA, Reigle MD, Selzman AA, et al. Use of ureteral stents in the management of major renal trauma with urinary extravasation: is there a role? J Endourol 1998; 12: 545–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Salimi J, Nikoobakht MR, Zareei MR. Epidemiologic study of 284 patients with urogenital trauma in three trauma center in Tehran. Urol J 2004; 1: 117–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Santucci RA, McAninch JM. Grade IV renal injuries: evaluation, treatment, and outcome. World J Surg 2001; 25: 1565–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kansas BT, Eddy MJ, Mydlo JH, et al. Incidence and management of penetrating renal trauma in patients with multiorgan injury: extended experience at an inner city trauma center. J Urol 2004; 172: 1355–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Voelzke BB, Leddy L. The epidemiology of renal trauma. Transl Androl Urol 2014; 3: 143–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zabkowski T, Skiba R, Saracyn M, et al. Analysis of renal trauma in adult patients: a 6-year own experiences of trauma center. Urol J 2015; 12: 2276–2279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baverstock R, Simons R, McLoughlin M. Severe blunt renal trauma: a 7-year retrospective review from a provincial trauma centre. Can J Urol 2001; 8: 1372–1376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Herschorn S, Radomski SB, Shoskes DA, et al. Evaluation and treatment of blunt renal trauma. J Urol 1991; 146: 274–276; discussion 276–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Krieger JN, Algood CB, Mason JT, et al. Urological trauma in the Pacific Northwest: etiology, distribution, management and outcome. J Urol 1984; 132: 70–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wright JL, Nathens AB, Rivara FP, et al. Renal and extrarenal predictors of nephrectomy from the national trauma data bank. J Urol 2006; 175: 970–975; discussion 975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McAleer IM, Kaplan GW, LoSasso BE. Renal and testis injuries in team sports. J Urol 2002; 168: 1805–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schmidlin F, Farshad M, Bidaut L, et al. Biomechanical analysis and clinical treatment of blunt renal trauma. Swiss Surg 1998: 237–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schmidlin FR, Iselin CE, Naimi A, et al. The higher injury risk of abnormal kidneys in blunt renal trauma. Scand J Urol Nephrol 1998; 32: 388–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schmidlin FR, Schmid P, Kurtyka T, et al. Force transmission and stress distribution in a computer-simulated model of the kidney: an analysis of the injury mechanisms in renal trauma. J Trauma 1996; 40: 791–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bernath AS, Schutte H, Fernandez RR, et al. Stab wounds of the kidney: conservative management in flank penetration. J Urol 1983; 129: 468–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moore EE, Shackford SR, Pachter HL, et al. Organ injury scaling: spleen, liver, and kidney. J Trauma 1989; 29: 1664–1666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kuo RL, Eachempati SR, Makhuli MJ, et al. Factors affecting management and outcome in blunt renal injury. World J Surg 2002; 26: 416–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kuan JK, Wright JL, Nathens AB, et al. American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Organ Injury Scale for kidney injuries predicts nephrectomy, dialysis, and death in patients with blunt injury and nephrectomy for penetrating injuries. J Trauma 2006; 60: 351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shariat SF, Roehrborn CG, Karakiewicz PI, et al. Evidence-based validation of the predictive value of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma kidney injury scale. J Trauma 2007; 62: 933–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dugi DD, 3rd, Morey AF, Gupta A, et al. American Association for the Surgery of Trauma grade 4 renal injury substratification into grades 4a (low risk) and 4b (high risk). J Urol 2010; 183: 592–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Buckley JC, McAninch JW. Revision of current American Association for the Surgery of Trauma renal injury grading system. J Trauma 2011; 70: 35–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Santucci RA, Wessells H, Bartsch G, et al. Evaluation and management of renal injuries: consensus statement of the renal trauma subcommittee. BJU Int 2004; 93: 937–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Alsikafi NF, Rosenstein DI. Staging, evaluation, and nonoperative management of renal injuries. Urol Clin North Am 2006; 33: 13–19, v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Buckley JC, McAninch JW. The diagnosis, management, and outcomes of pediatric renal injuries. Urol Clin North Am 2006; 33: 33–40, vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hoke TS, Douglas IS, Klein CL, et al. Acute renal failure after bilateral nephrectomy is associated with cytokine-mediated pulmonary injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 18: 155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Davis R, Jones JS, Barocas DA, et al. Diagnosis, evaluation and follow-up of asymptomatic microhematuria (AMH) in adults: AUA guideline. J Urol 2012; 188: 2473–2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Husmann DA. Pediatric genitourinary trauma. In: Wein AJ, Kava]oussi LR, Partin AW, et al. (eds) Campbell-Walsh urology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2016, 3539 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Aragona F, Pepe P, Patane D, et al. Management of severe blunt renal trauma in adult patients: a 10-year retrospective review from an emergency hospital. BJU Int 2012; 110: 744–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Morey AF, Brandes S, Dugi DD, 3rd, et al. Urotrauma: AUA guideline. J Urol 2014; 192: 327–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kawashima A, Sandler CM, Corl FM, et al. Imaging of renal trauma: a comprehensive review. Radiographics 2001; 21: 557–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Alonso RC, Nacenta SB, Martinez PD, et al. Kidney in danger: CT findings of blunt and penetrating renal trauma. Radiographics 2009; 29: 2033–2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Colling KP, Irwin ED, Byrnes MC, et al. Computed tomography scans with intravenous contrast: low incidence of contrast-induced nephropathy in blunt trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014; 77: 226–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Morey AF, McAninch JW, Tiller BK, et al. Single shot intraoperative excretory urography for the immediate evaluation of renal trauma. J Urol 1999; 161: 1088–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. McGahan JP, Richards JR, Jones CD, et al. Use of ultrasonography in the patient with acute renal trauma. J Ultrasound Med 1999; 18: 207–213; quiz 215–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Perry MJ, Porte ME, Urwin GH. Limitations of ultrasound evaluation in acute closed renal trauma. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1997; 42: 420–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ather MH, Noor MA. Role of imaging in the evaluation of renal trauma. J Pak Med Assoc 2002; 52: 423–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kitrey ND, Djakovic N, Gonsalves M, et al. EAU guidelines on urological trauma. 2017; 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mingoli A, La Torre M, Migliori E, et al. Operative and nonoperative management for renal trauma: comparison of outcomes. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2017; 13: 1127–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Santucci RA, McAninch JW, Safir M, et al. Validation of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma organ injury severity scale for the kidney. J Trauma 2001; 50: 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Buckley JC, McAninch JW. Revision of current American Association for the Surgery of Trauma renal injury grading system. J Trauma 2011; 70: 35–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Huber J, Pahernik S, Hallscheidt P, et al. Selective transarterial embolization for posttraumatic renal hemorrhage: a second try is worthwhile. J Urol 2011; 185: 1751–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Santucci RA, McAninch JM. Grade IV renal injuries: evaluation, treatment, and outcome. World J Surg 2001; 25: 1565–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Keihani S, Xu Y, Presson AP, et al. Contemporary management of high-grade renal trauma: results from the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Genitourinary Trauma study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2018; 84: 418–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Nash PA, Bruce JE, McAninch JW. Nephrectomy for traumatic renal injuries. J Urol 1995; 153: 609–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Carroll PR, Klosterman P, McAninch JW. Early vascular control for renal trauma: a critical review. J Urol 1989; 141: 826–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. McAninch JW, Carroll PR. Renal trauma: kidney preservation through improved vascular control-a refined approach. J Trauma 1982; 22: 285–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Gonzalez RP, Falimirski M, Holevar MR, et al. Surgical management of renal trauma: is vascular control necessary? J Trauma 1999; 47: 1039–1042; discussion 1042–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rosen MA, McAninch JW. Management of combined renal and pancreatic trauma. J Urol 1994; 152: 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Monstrey SJ, Beerthuizen GI, vander Werken C, et al. Renal trauma and hypertension. J Trauma 1989; 29: 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Matthews LA, Smith EM, Spirnak JP. Nonoperative treatment of major blunt renal lacerations with urinary extravasation. J Urol 1997; 157: 2056–2058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]