Abstract

Background:

Risk of community-acquired Clostridium difficile infection (CA-CDI) following antibiotic treatment specifically for urinary tract infection (UTI) has not been evaluated.

Methods:

We conducted a nested case-control study at Kaiser Permanente Northern California, 2007–2010, to assess antibiotic prescribing and other factors in relation to risk of CA-CDI in outpatients with uncomplicated UTI. Cases were diagnosed with CA-CDI within 90 days of antibiotic use. We used matched controls and confirmed case-control eligibility through chart review. Antibiotics were classified as ciprofloxacin (most common), or low risk (nitrofurantoin, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim), moderate risk, or high risk (e.g. cefpodoxime, ceftriaxone, clindamycin) for CDI. We computed the adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the relationship of antibiotic treatment for uncomplicated UTI and history of relevant gastrointestinal comorbidity (including gastrointestinal diagnoses, procedures, and gastric acid suppression treatment) with risk of CA-CDI using logistic regression analysis.

Results:

Despite the large population, only 68 cases were confirmed with CA-CDI for comparison with 112 controls. Female sex [81% of controls, adjusted odds ratio (OR) 6.3, CI 1.7–24), past gastrointestinal comorbidity (prevalence 39%, OR 2.3, CI 1.1–4.8), and nongastrointestinal comorbidity (prevalence 6%, OR 2.8, CI 1.4–5.6) were associated with increased CA-CDI risk. Compared with low-risk antibiotic, the adjusted ORs for antibiotic groups were as follows: ciprofloxacin, 2.7 (CI 1.0–7.2); moderate-risk antibiotics, 3.6 (CI 1.2–11); and high-risk antibiotics, 11.2 (CI 2.4–52).

Conclusions:

Lower-risk antibiotics should be used for UTI whenever possible, particularly in patients with a gastrointestinal comorbidity. However, UTI can be managed through alternative approaches. Research into the primary prevention of UTI is urgently needed.

Keywords: antimicrobial stewardship, Clostridium difficile infection, community-based studies, outpatient care, urinary tract infection

Introduction

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is a critical challenge. While most cases are acquired in hospitals or long-term care facilities, recent studies suggest that community-acquired CDI (CA-CDI), defined as cases that occur without a healthcare facility admission in the preceding 90 days, accounts for about 20–40% of the case burden.1,2 Transmission from the community is believed to be an important factor in the burden of hospital-acquired CDI. Specific antibiotic agents predict CA-CDI risk.1–5 However, past studies included patients with a variety of underlying infections, making it difficult to apply to the knowledge for specific infections. Urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common indications for outpatient antibiotic treatment.6,7 Therefore, we conducted a nested case-control study focusing on outpatient UTI antibiotic prescribing to explore strategies to reduce CA-CDI risk.

Methods

The study was approved by the local institutional review board and a waiver of informed consent was granted.

Setting

Kaiser Permanente Northern California provides capitated, integrated, and comprehensive healthcare to 3.9 million members. No resource has been disseminated to standardize the treatment of UTI. Two Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines were used during the study period, ‘Guidelines for antimicrobial treatment of uncomplicated acute bacterial cystitis and acute pyelonephritis in women’,8 and ‘Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults’.9 To detect CDI, the health plan uniformly used the enzyme immunoassay test that detects toxins A and B.10

Study population

The study cohort included adults who received at least one antibiotic prescription for acute uncomplicated UTI in an outpatient care setting (including the emergency department or via a telephone visit) during 2007–2010. We excluded those who had a diagnosis of CDI recorded in the 100 days preceding their UTI diagnoses, were pregnant, hospitalized, or living in a skilled nursing facility or long-term care facility. We also excluded those who were immunocompromised, defined as having a malignancy or human immunodeficiency virus, a history of steroid use equivalent to at least 20 mg/day of prednisone for 2 months or longer, or being on dialysis. UTI was defined using International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 diagnosis codes 599.0, 595.0, and 595.9. Uncomplicated UTI was confirmed independently by two infectious disease physicians and an antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist (lead author) using chart review.

CA-CDI cases

Members of the eligible cohort who had loose stools and a positive CDI test at least 3 days after their antibiotic start date and within 90 days after their antibiotic stop date were defined as cases. The date of stool collection was defined as the case’s index date.

Controls

For each case, we randomly selected two potential controls with antibiotic-treated UTI but no CA-CDI diagnosis within the critical time period after starting and stopping their antibiotic prescription. Each potential control was matched to its case on medical center, age, and date of visit for UTI, using the closest age and date match possible. Potential controls were assigned an index date corresponding to the index date of the matched case.

Data collection

A data analyst obtained patient demographic information, antibiotic dispensing, and past diagnoses and procedures from the electronic medical record. Patient age, sex, and race/ethnicity were obtained from membership data. We obtained details of antibiotic regimens that ended within the 90-day period preceding the index date, including the agent, dose (mg/pill), frequency (pills/day), and duration (days). We also obtained gastric acid suppression treatment, including use of proton pump inhibitors and histamine-2 receptor antagonists, for the 12-month period before the index date. For patients who used both drug classes, we focused on the class used most recently before the index date. The patient’s past gastrointestinal diagnoses (regional enteritis, ulcerative colitis, diverticula of intestine, and other functional digestive disorders) and gastrointestinal procedures (ICD-9 procedure codes 42–54) were obtained from ICD-9 codes recorded on the electronic medical record during the 12-month period before the index date. We also calculated the Charlson comorbidity index using ICD-9 diagnostic codes, excluding peptic ulcer disease because it is related to gastric acid suppression treatment. This index assigns one to six points to each of 22 conditions. It was originally developed to predict the risk of death in the subsequent 12 months but has been used extensively in observational research as a summary measure of comorbidity.

The infectious disease team (two physicians and one pharmacist) reviewed charts to identify the reasons for all antibiotic treatments during the 90-day period before the index date. Variables included past medical history, urinary symptoms (dysuria, urgency, frequency, suprapubic pain or tenderness), fever, urinary analysis, urinary culture date, urinary organism isolated, and results of antibiotic susceptibility testing from clinical microbiology data, if available. Although sensitivity to penicillin and amoxicillin was not performed, sensitivity to ampicillin was considered a substitute. Similarly, cefazolin was considered a substitute for cephalexin and dicloxacillin, and ceftriaxone a substitute for cefpodoxime.

Statistical analysis

We defined ‘gastrointestinal comorbidity’ as including relevant gastrointestinal diagnoses (including functional disorder and diverticulitis), procedures (including gallbladder or biliary tract, intestinal, and gastric operations), or use of gastric acid suppression treatment (including proton pump inhibitors and H-2 receptor antagonists). Ciprofloxacin was a commonly used antibiotic, but others were used less commonly. We combined the less commonly used antibiotic agents into groups based on the magnitude of their association with CDI risk as published in the literature:11 high risk (cefpodoxime, ceftriaxone, clindamycin), moderate risk (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, ampicillin, azithromycin, cefuroxime, cephalexin, erythromycin), and low risk (nitrofurantoin, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and dicloxacillin). For patients who used multiple antibiotic agents, we classified each patient based on their highest-risk antibiotic exposure within the 90 days before their index date, with ciprofloxacin placed in between low risk and moderate risk. We also counted the total number of antibiotic courses and assessed the duration of use of antibiotic.

We used logistic regression analysis to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the relationships between antibiotic use and risk of CA-CDI. Variables were retained in the model if they were significant at an α of 0.05 or functioned as confounders. p Values were estimated using the χ2 test. We also estimated the population attributable risk, that is, the proportion of cases that would not have occurred in the eligible study population, if one could replace higher-risk antibiotic exposures with lower-risk exposures.12 All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Eligible cases and controls

The number of potential CDI cases identified in the eligible cohort was 99. During case confirmation, 31 patients were excluded because they resided in a skilled nursing facility or long-term care facility. Thus, the number of confirmed CDI cases was 68. Two potential controls were selected per potential CDI case, resulting in 198 potential controls. Following confirmation, 62 were excluded because they resided in a skilled nursing facility or long-term care facility. In addition, 24 were excluded because they did not have antibiotic exposure during the 90-day period before their index date, because case-control matching was not to the exact day. Thus, the number of confirmed controls was 112.

Characteristics of cases and controls

Characteristics of cases and controls are shown in Table 1. Cases and controls had similar age distributions due to matching. Compared with the controls, CDI cases were more likely to be women (96% versus 81%, p < 0.01). They also were more likely than controls to have a Charlson comorbidity (any Charlson comorbidity compared with none: 21% versus 6%, p < 0.01). Cases and controls were broadly similar with respect to presence of recurrent UTI and fever at the time of the UTI diagnosis. Among 12 cases and 40 controls whose first course of antibiotic for UTI was nitrofurantoin or sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, 1 case (8%) and 6 controls (15%) had recurrent UTI. Cases were somewhat more likely to have used an antibiotic for reasons other than UTI during the 90-day period before their index date, to have visited an emergency department for their index UTI, and to have a positive urinalysis and urine culture test, although these differences were not statistically significant. Among the 22% of cases and 15% of controls who used antibiotic for reasons other than UTI, the indications were cellulitis, bronchitis, dental infection, and diverticulitis. Case-control differences in history of gastrointestinal comorbidity were striking (68% versus 39%, p < 0.001), and included differences in use of a proton pump inhibitor (32% versus 13%, p < 0.001), a gastrointestinal diagnosis (31% versus 13%, p < 0.01), and a gastrointestinal procedure (10% versus 4%, p < 0.07).

Table 1.

Characteristics of outpatients with urinary tract infection (UTI) who received an antibiotic, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, 2007–2010, in relation to risk of community-acquired Clostridium difficile infection.

| Characteristic | Cases (n =

68) |

Controls (n =

112) |

p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age, years | |||||

| 18–49 | 18 | 26 | 30 | 27 | * |

| 50–64 | 18 | 26 | 30 | 27 | |

| 65–79 | 17 | 25 | 34 | 30 | |

| 80+ | 15 | 22 | 18 | 16 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 3 | 4 | 21 | 19 | <0.01 |

| Female | 65 | 96 | 91 | 81 | |

| Race | |||||

| White | 44 | 65 | 64 | 57 | 0.32 |

| African-American | 6 | 9 | 7 | 6 | |

| Asian-American | 2 | 3 | 13 | 12 | |

| Multiracial | 5 | 7 | 8 | 7 | |

| Unknown | 11 | 16 | 20 | 18 | |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | |||||

| 46–59 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| ⩾60 | 58 | 85 | 87 | 78 | |

| Not measured | 7 | 10 | 25 | 22 | 0.06 |

| Charlson comorbidity index$ | |||||

| None | 54 | 79 | 105 | 94 | <0.01 |

| Any (except ulcer) | 14 | 21 | 7 | 6 | |

| Recurrent UTI | |||||

| No | 59 | 87 | 99 | 88 | 0.82 |

| Yes | 9 | 13 | 13 | 12 | |

| Fever | |||||

| Not taken | 7 | 10 | 8 | 7 | |

| No | 50 | 74 | 92 | 82 | 0.16 |

| Yes | 7 | 10 | 12 | 11 | |

| Antibiotic for reasons other than UTI during 90-day period before index | |||||

| No | 53 | 78 | 95 | 85 | 0.32 |

| Yes | 15 | 22 | 17 | 15 | |

| Emergency department for index UTI | |||||

| No | 55 | 81 | 99 | 88 | 0.19 |

| Yes | 13 | 19 | 13 | 12 | |

| Urinalysis | |||||

| Not done | 11 | 16 | 19 | 17 | |

| Negative | 7 | 10 | 18 | 16 | 0.37 |

| Positive | 50 | 74 | 75 | 67 | |

| Urine culture | |||||

| Not performed | 16 | 24 | 30 | 27 | |

| Negative | 15 | 22 | 33 | 29 | 0.27 |

| Positive | 37 | 54 | 49 | 44 | |

| Any pre-existing gastrointestinal comorbidity | |||||

| None | 22 | 32 | 68 | 61 | |

| Any | 46 | 68 | 44 | 39 | <0.001 |

| Gastric acid suppression‡ | |||||

| None | 35 | 52 | 80 | 72 | |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 22 | 32 | 15 | 13 | <0.001 |

| H-2 receptor antagonist | 11 | 16 | 17 | 15 | 0.35 |

| Gastrointestinal diagnosis§ | |||||

| None | 47 | 69 | 97 | 87 | <0.01 |

| Any | 21 | 31 | 15 | 13 | |

| Gastrointestinal operation¶ | |||||

| None | 61 | 90 | 108 | 96 | |

| Any | 7 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 0.07 |

Controls were matched to cases on age to the closest year possible.

Included 6 cases and 3 controls with diabetes, 6/2 with chronic pulmonary disease, 5/0 with renal disease, 4/1 with congestive heart failure, 4/1 with peripheral vascular disease, and 4/5 with other comorbidities.

Gastric acid suppression treatment was obtained from pharmacy data for the 12-month period before the index date. Patients were assigned to the drug used more recently before the index date.

Two cases and 4 controls had a functional disorder, 9 cases and 10 controls had diverticulitis.

The cohort included 3 cases and 1 control with a gall bladder or biliary tract operation; 3 cases with an intestinal operation; 1 case and 1 control with an operation on the appendix; 1 control with a hernia repair; 1 control with an operation on the stomach; and 1 control with a nonspecified gastrointestinal operation.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Relationship of antibiotic exposure with risk of CA-CDI

Recall that we required eligible cases and controls to have exposure to an antibiotic in the 90 days before their index date. Among those exposed to a low-risk antibiotic, 100% used either nitrofurantoin or sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim. After adjusting for sex, history of a gastrointestinal comorbidity, and Charlson comorbidity index, we observed striking associations between antibiotic risk group and risk of CDI (Table 2). Using the low-risk group as the referent, the adjusted OR was 2.7 (CI 1.0–7.2) for ciprofloxacin, 3.6 (CI 1.2–11) for moderate-risk antibiotics, and 11.2 (CI 2.4–52) for high-risk antibiotics. Past gastrointestinal comorbidities (OR 2.3, CI 1.1–4.8) and Charlson comorbidity (OR 2.8, CI 1.4–5.6) were also associated with CA-CDI risk, while women were at 6.3-fold greater risk than men (CI 1.7–24). Because risk was so much higher in women, we conducted a subgroup analysis restricted to women. We observed the same pattern of association with use of antibiotics (compared with low-risk agents: ciprofloxacin, OR 2.9, CI 1.1–8.0; moderate risk, OR 3.7, CI 1.2–11; and high risk, OR 8.0, CI 1.8–37), with ORs of 2.2 for Charlson comorbidity (CI 1.0–4.9) and 3.0 for gastrointestinal comorbidity (CI 1.5–6.2).

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the association of antibiotic use and other factors with risk of Clostridium difficile infection in outpatient patients with urinary tract infection (UTI) who received an antibiotic, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, 2007–2010.a

| Characteristic* | Cases (n =

68) |

Controls (n = 112) |

% | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | |||||

| Sex (female versus male) | 65 | 96 | 91 | 81 | 6.3 | 1.7–24 | <0.01 |

| Gastrointestinal (any versus none)$ | 46 | 68 | 44 | 39 | 2.3 | 1.1–4.8 | 0.03 |

| Charlson comorbidity (any versus none) | 14 | 21 | 7 | 6 | 2.8 | 1.4–5.6 | <0.01 |

| Antibiotic risk group‡ | |||||||

| Low risk | 7 | 10 | 30 | 27 | 1.0 | Ref. | – |

| Ciprofloxacin | 32 | 47 | 56 | 50 | 2.7 | 1.0–7.2 | 0.05 |

| Moderate risk | 19 | 28 | 22 | 20 | 3.6 | 1.2–11 | 0.02 |

| High risk | 10 | 15 | 4 | 4 | 11.2 | 2.4–52 | <0.01 |

Controls were matched to cases on age to the closest year possible.

Gastric acid suppression treatment included use of a proton pump inhibitor or H2 receptor antagonist and was obtained from pharmacy data for 12-month period before the index date. We also obtained the patient’s history of a gastrointestinal diagnosis (regional enteritis, ulcerative colitis, diverticula of intestine, and other functional digestive disorders) and gastrointestinal procedures (42.0–54.99).

Indicates the high-risk antibiotic agent used during the 90 days before the index date, coded using a hierarchy: high risk (cefpodoxime, ceftriaxone, clindamycin) > moderate risk (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, ampicillin, azithromycin, cefuroxime, cephalexin, erythromycin) > ciprofloxacin > low risk (nitrofurantoin, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, dicloxacillin).

We used the results of the analysis in Table 2 to estimate the population attributable risk related to the antibiotic agent, using prevalence levels measured in the controls. Based on the low resistance rate to nitrofurantoin and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim in our patient cohort, we assume that 85% of the population could have been switched to a low-risk antibiotic (nitrofurantoin or sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim). We estimate that 44% of the CA-CDI cases would have been prevented, with the majority (60%) having come from the ciprofloxacin group, because this agent was used so frequently.

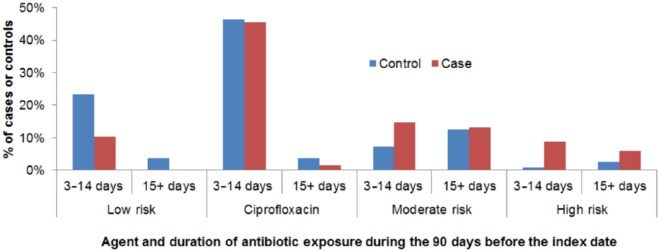

We found no case-control difference in the number of antibiotic courses received during the 90 days before the diagnosis of C. difficile (one course, 62% of cases, 67% of controls; two courses, 18% and 14%; three to five courses, 21% and 19%, respectively, p = 0.74). The duration of antibiotic use by antibiotic risk level (low, ciprofloxacin, moderate, high) is shown in Figure 1. For patients who used multiple antibiotics, the duration is the sum of the total across risk levels. A total of 21% of cases and 22% of controls used an antibiotic for 15 days or longer during the 90 days before their index date. We noted that the most common regimen was ciprofloxacin for up to 14 days. We could not perform a detailed analysis of duration of antibiotics because of the small sample size and the need to account for different antibiotic risk levels.

Figure 1.

Distribution of antibiotic agent and duration among Clostridium difficile infection cases and controls with urinary tract infection who received an antibiotic in an outpatient setting, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, 2007–2010.

Urinary pathogens and antibiotic sensitivities

Among those with a positive urine culture (39 cases, 50 controls), Escherichia coli was the most common pathogen (29 cases, 35 controls) (Table 3). Among cases with pathologically confirmed UTI, 4 out of 29 (14%) of E. coli strains were resistant to nitrofurantoin, while 34% were resistant to sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim. Among controls, only 1 out of 34 (3%) was resistant to nitrofurantoin, while 20% were resistant to sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim.

Table 3.

Urinary pathogens and antibiotic sensitivities among 39 cases with Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) and 50 controls with a positive urine culture who received an antibiotic in an outpatient setting, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, 2007–2010.

| CDI cases* | No. diagnosed | No. tested | Number sensitive/number

tested |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMP | A/S | CZ | CIPRO | GEN | CRE‡ | NITRO | TZP | TOBRA | SMX/TMP | |||

| Escherichia coli | 29 | 27 | 16/29 | 21/29 | 28/29 | 26/29 | 27/29 | 29/29 | 25/29 | 28/28 | 22/25 | 19/29 |

| Enterococcus faecium | 1 | 1 | 0/1 | –$ | – | 0/1 | – | – | 1/1 | – | – | – |

| Gram-negative rods | 1 | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Klebsiella pneumonia | 4 | 4 | 0/1 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 3/4 | 4/4 | 3/4 | 3/4 |

| Proteus mirabilis | 2 | 2 | 1/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | – | 2/2 |

| Pseudomonas aerogenosa | 1 | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Staphylococcus. species | 3 | 1 | – | – | – | 1/1 | 1/1 | – | 1/1 | – | – | 1/1 |

| Controls* | ||||||||||||

| E. coli | 35 | 35 | 19/34 | 22/34 | 33/34 | 32/34 | 33/34 | 34/34 | 33/34 | 34/34 | 29/30 | 24/30 |

| E. faecium | 1 | 1 | 1/1 | – | – | 1/1 | – | – | 1/1 | – | – | – |

| Gram-negative rods | 2 | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Group B β hemolytic Streptococcus agalactiae | 2 | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| K. pneumonia | 4 | 4 | 2/3 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 2/4 | 4/4 | 2/2 | 4/4 |

| Morganella morganii | 1 | 1 | – | – | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| P. mirabilis | 3 | 3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 0/3 | 3/3 | 2/2 | 3/3 |

| P. aerogenosa | 1 | 1 | – | 0/1 | – | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | – | 1/1 | 1/1 | – |

| Staphylococcus species | 2 | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

One CDI case and one control had both E. coli and P. mirabilis; one case had both E. coli and Klebsiella.

‘–’ = not tested for the antibiotic.

Ertapenem, imipenem, or meropenem.

AMP, ampicillin; A/S, ampicillin/sulbactam; CRE, carbapenem; CZ, cefazolin; CIPRO, ciprofloxacin; GEN, gentamicin; NITRO, nitrofurantoin; SMX/TMP, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim; TOBRA, tobramycin; TZP, tazobactam/piperacillin.

Discussion

We studied the association of antibiotic exposure with risk of CA-CDI in outpatients with UTI. Our results for patients with UTI were similar to past studies that examined a wide range of infections.11,12 To our knowledge, this case-control study is the first to focus on outpatient UTI patients. We are not aware of any study focused on inpatients with UTI.

Our study has two key limitations. First, because CA-CDI is rare, only 68 cases were identified for this study, despite its setting in a large population exceeding 3 million persons and the 4-year period of accrual. Second, few men were included in the study. Due to the low prevalence of UTI in men, our cohort consisted mostly of women. Thus, our study findings may not generalize well to men.

Notwithstanding the small sample size, the study provided significant and novel results. In outpatients with UTI, patient comorbidity was associated with increased risk for CA-CDI, ciprofloxacin and other moderate- to high-risk agents were frequently selected in place of lower-risk agents, and the combination of patient comorbidity with use of moderate- to high-risk antibiotics was associated with greatly increased CA-CDI risk.

Risk of CA-CDI was 6.3-fold higher (CI 1.7–24) in women than men, although few men were included in the study. This finding is consistent with two recent studies, although the association we measured was larger than past reports.4,13 In population-based studies in Connecticut (2006) and North Carolina (2005), women had about two times the risk of CA-CDI observed in men.

We observed that a past gastrointestinal comorbidity was associated with 2.3-fold (CI 1.1–4.8) increased risk of CA-CDI. This is consistent with a recent meta-analysis.14 Past gastrointestinal comorbidity was highly prevalent, affecting 68% of the cases and 39% of the controls, with gastric acid suppression therapy affecting 48% of the cases and 28% of controls. Nongastrointestinal comorbidity was associated with 2.8-fold (CI 1.4–5.6) increased risk of CDI, affecting 21% of the cases but only 6% of the controls. These results are consistent with past studies, although most were focused on hospital-associated CDI cases with substantially greater comorbidity burden.15 A gastrointestinal or Charlson comorbidity combined with use of ciprofloxacin or a more risky antibiotic was associated with 10–20 times greater risk of CA-CDI compared with the combination of no gastrointestinal comorbidity and low-risk antibiotic. The high prevalence of a gastrointestinal comorbidity in our relatively healthy population suggests that reducing overall antibiotic use in UTI management is important for combating CA-CDI in the outpatient setting. Furthermore, antibiotic consumption in community-based patients has been linked to antibiotic resistance at both the individual and community levels.16 Because we can readily identify patients with comorbidity from their clinical history, it should be possible to shift antibiotic use to lower-risk agents in this especially vulnerable population.

Ciprofloxacin, a member of the fluoroquinolone class, was the most frequently used antibiotic. This is consistent with a national report on uncomplicated UTI in US women, 2002–2011.17 Fluoroquinolone disrupts microbiome composition and increases the risk of colonization and infection with resistant and multidrug-resistant organisms.18,19 In July 2016, the US Food and Drug Administration updated its warning for fluoroquinolones’ disabling side effects, which involve tendons, muscles, joints, nerves, and the central nervous system.20 Although effective for UTI, fluoroquinolones should be reserved for the most serious cases.21 All ciprofloxacin users were prescribed a 3-to 14-day supply, with 10-day supply being the most common, despite the recommended 3-day regimens for UTI. Broad-spectrum cephalosporins have also been associated with microbiome disruption, colonization, and infection with multidrug-resistant organisms including CDI,11,21 and they have inferior efficacy for UTI.22

Although we were unable to perform a detailed analysis to determine the relationship between treatment durations that were longer than necessary and risk of CA-CDI, we recommend that practitioners consider prescribing the shortest effective duration of treatment for outpatient UTI. Despite IDSA guidelines for uncomplicated UTI, nearly 50% of cases and controls in our study received up to 14 days of ciprofloxacin, while more than 20% of cases and controls had antibiotics for at least 15 days. Greater adherence to guidelines would decrease unnecessary, prolonged and inappropriate antibiotic exposure, thereby decreasing the risk of CA-CDI.

Nitrofurantoin and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim were associated with lowest risk of CA-CDI compared with other antibiotic agents. Among pathologically confirmed UTI, 34% of cases and 20% of controls in our study were resistant to sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim.21 Previous studies reported 20% of pathologically confirmed UTI cases to be resistant to sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim.23,24 Given these findings, one can recommend nitrofurantoin for first-line empiric antibiotic for UTI.21 Until recently, nitrofurantoin was contraindicated in patients with a creatinine clearance less than 60 ml/min, however, in 2015, this cutpoint was reduced to less than 30 ml/min for short-term use (⩽7 days).25 Of note, no patient in our study had an estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 30 ml/min. Although not used in our study, fosfomycin trometamol (3 g in a single dose) is another recommended option, although its efficacy is inferior to other standard short-course regimens.21 For patients with UTI with multiple risk factors, we recommend nitrofurantoin as the first-line empiric antibiotic. Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim could also be considered as a potential first-line antibiotic for UTI in locations with at least 80% urinary pathogen sensitivity.21 For patients who are intolerant to both antibiotics, fosfomycin may be used as an alternative.

In addition to postmenopausal status, some women are prone to recurrent UTIs (at least twice in 6 months or at least three times in 12 months) with sexual activity being a key risk factor and the mode of transmission being transfer of fecal matter from the rectum to the vagina.26 Continuous low-dose antibiotics and postcoital antibiotics have been suggested as a management strategy.27–29 Long-term low-dose UTI prophylaxis with nitrofurantoin is associated with rare but serious adverse pulmonary and liver reactions.29 Long-term use of sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim may lead to rapid antibiotic resistance.21

Providers should consider behavioral and nonantimicrobial approaches to UTI management. Risk of progression of outpatient UTI to tissue invasion or sepsis is minimal, and studies have reported clinical cure can be achieved in 25–42% of women with uncomplicated cystitis treated with placebo alone.30,31 For patients who are presumed to be at low risk for progression of infection, clinicians should consider educating patients on the self-limiting nature of uncomplicated UTI, the benefit of watchful waiting, and the harm associated with overuse of antibiotics, including adverse effects and antibiotic resistance. Awareness of the harms could encourage patients to seek UTI symptom management instead of UTI treatment when clinically applicable. This would involve delaying an antibiotic order until the patient complains of pain.32 Delaying antibiotic prescriptions and restriction of antibiotic treatment to symptomatic cases only could reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing.33 Nonantimicrobial therapies including cranberry juice and tablets, probiotics, and immunoprophylaxis using Uro-Vaxom E. coli extract (Terra-Laba, Zagreb, Croatia) have shown promising results.33 A recent Cochrane review concluded that short-term use of methenamine hippurate is effective in preventing recurrent UTIs in patients with a normal renal tract.34

Prevention is an under-researched aspect of UTI management. Patient education on correct wiping after using the toilet, adequate hydration and frequent urination, precoital bathing and postcoital voiding, avoiding feminine products, and avoiding use of certain birth control products may reduce the incidence of UTI. Further research together with public health efforts to promote improved hygiene, sexual practices, and health behaviors among girls and women is urgently needed to reduce UTI-related morbidity and use of antibiotics for UTI.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Community Benefit Program.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ORCID iD: Lisa J. Herrinton  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5702-7162

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5702-7162

Contributor Information

Ivy Y. Ge, Inpatient Pharmacy, Kaiser Permanente Northern California South San Francisco Medical Center, 1200 El Camino Real, 3rd Floor, South San Francisco, CA 94080, USA.

Helene B. Fevrier, Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente, Oakland, CA, USA

Carol Conell, Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente, Oakland, CA, USA.

Malika N. Kheraj, Department of Infectious Disease, Kaiser Permanente Redwood City Medical Center, Redwood City, CA, USA

Alexander C. Flint, Department of Neurology, Kaiser Permanente Redwood City Medical Center, Redwood City, CA, USA

Darvin S. Smith, Department of Infectious Disease, Kaiser Permanente Redwood City Medical Center, Redwood City, CA, USA

Lisa J. Herrinton, Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente, Oakland, CA, USA

References

- 1. Dumyati G, Stevens V, Hannett GE, et al. Community-associated Clostridium difficile infections, Monroe County, New York, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 2012; 18: 392–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Khanna S, Pardi DS, Aronson S, et al. The epidemiology of community-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Durham DP, Olsen MA, Dubberke ER, et al. Quantifying transmission of Clostridium difficile within and outside healthcare settings. Emerg Infect Dis 2016; 22: 608–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kutty PK, Woods CW, Sena AC, et al. Risk factors for and estimated incidence of community-associated Clostridium difficile infection, North Carolina, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 2010; 16: 198–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deshpande A, Pasupuleti V, Thota P, et al. Community-associated Clostridium difficile infection and antibiotics: a meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013; 68: 1951–1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Niska R, Bhuiya F, Xu J. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2007 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Report 2010; 6: 1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shapiro DJ, Hicks LA, Pavia AT, et al. Antibiotic prescribing for adults in ambulatory care in the USA, 2007–09. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014; 69: 234–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Warren JW, Abrutyn E, Hebel R, et al. Guidelines for antimicrobial treatment of uncomplicated acute bacterial cystitis and acute pyelonephritis in women: Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Clin Infectious Dis 1999; 29: 745–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 40: 643–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010; 31: 431–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brown KA, Khanafer N, Daneman N, et al. Meta-analysis of antibiotics and the risk of community-associated Clostridium difficile infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57: 2326–2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rothman K, Greenland S. Modern epidemiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Centers for Disease Control. Surveillance for community-associated Clostridium difficile–Connecticut, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008; 57: 340–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Janarthanan S, Ditah I, Adler DG, et al. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and proton pump inhibitor therapy: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 1001–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Evans CT, Safdar N. Current trends in the epidemiology and outcomes of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60(Suppl. 2): S66–S71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bell S, Davey P, Nahwani D, et al. Risk of AKI with gentamicin as surgical prophylaxis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014; 25: 2625–2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kobayashi M, Shapiro DJ, Hersh AL, et al. Outpatient antibiotic prescribing practices for uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women in the United States, 2002–2011. Open Forum Infect Dis 2016; 3: ofw159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Langdon A, Crook N, Dantas G. The effects of antibiotics on the microbiome throughout development and alternative approaches for therapeutic modulation. Genome Med 2016: 8: 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Paterson DL. ‘Collateral damage’ from cephalosporin or quinolone antibiotic therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38(Suppl. 4): S341–S345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA advises restricting fluoroquinolone antibiotic use for certain uncomplicated infections; warns about disabling side effects that can occur together, https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm500143.htm (accessed 1 March 2017).

- 21. Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: a 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52: e103–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hooton TM, Roberts PL, Stapleton AE. Cefpodoxime vs ciprofloxacin for short-course treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis: a randomized trial. JAMA 2012; 307: 583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bouza E, Burillo A, Muñoz P. Antimicrobial therapy of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. Med Clin North Am 2006; 90: 1141–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Loo VG, Poirier L, Miller MA, et al. A predominantly clonal multi-institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 2442–2449. Erratum in: N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. The American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatric Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63: 2227–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Epp A, Larochelle A, Lovatsis D, et al. Recurrent urinary tract infection. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2010; 32: 1082–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nickel JC. Practical management of recurrent urinary tract infections in premenopausal women. Rev Urol 2005; 7: 11–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vahlensieck W, Perepanova T, Johansen TEB, et al. Management of uncomplicated recurrent urinary tract infections. Eur Urol Suppl 2016; 15: 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Muller AE, Verhaegh EM, Harbarth S, et al. Nitrofurantoin’s efficacy and safety as prophylaxis for urinary tract infections: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis of controlled trials. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017; 23: 355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Christiaens TC, De Meyere M, Veschraegen G, et al. Randomized controlled trial of nitrofurantoin versus placebo in the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infection in adult women. Br J Gen Pract 2002; 52: 72–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ferry SA, Holm SE, Stenlund H, et al. Clinical and bacteriological outcome of different doses and duration of pivmecillinam compared with placebo therapy of uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection in women: the LUTIW project. Scan J Prim Health Care 2007; 25: 49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Duane S, Beatty P, Murphy AW, et al. Exploring experiences of delayed prescribing and symptomatic treatment for urinary tract infections among general practitioners and patients in ambulatory care: a qualitative study. Antibiotics 2016; 5: E27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Al-Badr A, Al-Shaikh G. Recurrent urinary tract infections management in women: A review. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2013; 13: 359–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee BS, Bhuta T, Simpson JM, et al. Methenamine hippurate for preventing urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 10: CD003265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]