Abstract

Acinetobacter baumannii is a Gram-negative nosocomial pathogen that causes soft tissue infections in patients who spend a long time in intensive care units. This recalcitrant bacterium is very well known for developing rapid drug resistance, which is a combined outcome of its natural competence and mobile genetic elements. Successful efforts to treat these infections would be aided by additional information on the physiology of A. baumannii. Toward that end, we recently reported on a small RNA (sRNA), AbsR25, in this bacterium that regulates the genes of several efflux pumps. Because sRNAs often require the RNA chaperone Hfq for assistance in binding to their cognate mRNA targets, we identified and characterized this protein in A. baumannii. The homolog in A. baumannii is a large protein with an extended C terminus unlike Hfqs in other Gram-negative pathogens. The extension has a compositional bias toward glycine and, to a lower extent, phenylalanine and glutamine, suggestive of an intrinsically disordered region. We studied the importance of this glycine-rich tail using truncated versions of Hfq in biophysical assays and complementation of an hfq deletion mutant, finding that the tail was necessary for high-affinity RNA binding. Further tests implicate Hfq in important cellular processes of A. baumannii like metabolism, drug resistance, stress tolerance, and virulence. Our findings underline the importance of the glycine-rich C terminus in RNA binding, ribo-regulation, and auto-regulation of Hfq, demonstrating this hitherto overlooked protein motif to be an indispensable part of the A. baumannii Hfq.

Keywords: virulence factor, gene regulation, biofilm, bacterial adhesion, RNA binding protein, AbsR25, chaperone, Gram negative pathogen, resistance, small RNA, intrinsically disordered protein, pathogen

Introduction

Acinetobacter baumannii is a recalcitrant Gram-negative pathogen notorious for prolonged persistence in intensive care units. It is a major cause of infection outbreaks in hospitals and is responsible for as much as 80% of the reported infections in some countries (1, 2). The ability of A. baumannii to form resistant biofilms and survive harsh desiccated conditions, compounded by resistance to multiple antibiotics and common disinfectants, makes it even more difficult to eradicate it from the hospital settings (3, 4). The alarming rate of multidrug resistance, extensive drug resistance, and pan-drug resistance and the prevalence of the recently discovered metallo-β-lactamases among A. baumannii clinical strains warrant its status as a “superbug” (5–7).

Much of the information on pathogenesis and virulence factors of A. baumannii has come to light only recently (8). Small RNA (sRNA)3-based regulation of pathogenesis is a common and effective strategy for a pathogen to fine-tune the expression of virulence genes at the post-transcriptional level (9). Recently, our group reported a novel sRNA in A. baumannii, AbsR25, which regulates the expression of a few efflux pump genes, including a novel fosfomycin efflux pump (10, 11). Similar sRNAs have been reported to be involved in regulation of virulence, metabolism, stress tolerance, and antibiotic resistance in other bacterial pathogens (9, 12). However, most of the sRNA in Gram-negative bacteria require an RNA chaperone, Hfq, to exert their effects (13). Hfq is a central component of the global post-transcriptional regulatory machinery that involves sRNA and their target mRNA (14). It belongs to the Sm-like (LSm) class of proteins that carry Sm domains similar to those found in eukaryotic RNA-binding proteins. Originally discovered in Escherichia coli as a host factor required for replication of Qβ bacteriophage (hence the name Hfq), Hfq is now recognized as an RNA chaperone that facilitates the interaction of sRNAs with their cognate mRNA targets, thereby altering their stability and/or translation (13). Hfq forms a toroid of six monomers that contain an N-terminal α-helix, followed by five antiparallel β-sheets and an unstructured C-terminal tail. The toroid presents two different faces, proximal and distal, and the rim of the toroid for RNA interaction. Recent studies have speculated that the rim of the toroid and the C terminus tail somehow assist in this interaction (14). Being an important factor in sRNA-mediated regulation throughout the Gram-negative species, the requirement of Hfq becomes a prerequisite for the so-called fine-tuning of regulation of gene expression (15).

Initial studies with inactivation of hfq in E. coli resulted in a myriad of effects like reduced growth rate and impaired stress tolerance asserting a general role of Hfq in bacterial physiology (16). Later studies on hfq mutants of pathogens like Vibrio cholerae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella enterica, and Klebsiella pneumoniae reported attenuated virulence in murine models, defective secretory profiles, reduced adhesion and invasion of mammalian cells and dissemination into organs, motility defects, and decreased expression of various virulence factors (17–20). These observations stem from the involvement of Hfq-dependent sRNA in regulation of these key processes, which later led to experimental identification of these sRNA (21).

However, the sRNA landscape of A. baumannii remains largely unexplored, and so does the role of this extra long stretch of Hfq in the biology of A. baumannii. We describe here the hfq gene and its corresponding protein product in A. baumannii ATCC 17978. The Hfq protein of A. baumannii is unusual, as it carries an unusually long C terminus rich in glycine residues. We studied the functional importance of this glycine-rich region of Hfq by complementing the hfq deletion mutant with full-length as well as truncated versions of Hfq. Contrary to the previously held view that the repetitive glycine residues might not be of much importance (22), our experiments conclude that this flexible C-terminal tail is an integral functional part of A. baumannii Hfq.

Results

A. baumannii codes for an unusually long Hfq protein with a glycine-rich C terminus

A sequence similarity search using E. coli Hfq as query against the A. baumannii ATCC 17978 proteome returned a 168-amino acid-long protein, A1S_3785. Multiple-sequence alignment of this sequence with well-studied counterparts from other bacterial species revealed a significant level of similarity at the N-terminal region (Fig. S1) with conserved Gln-8, Phe-39, Lys-56, and His-57, known to be involved in RNA binding (23). The C-terminal region (CTR), however, carries a distinctive repetitive GGFGGQ amino acid pattern (Fig. S1), suggesting a duplication event in the evolutionary history of A. baumannii, as the codon usage in this region is similar to the rest of the A. baumannii proteins (Table S1).

This glycine-rich CTR appears to be a signature of the Moraxellaceae family (Fig. S2), with the well-studied Hfq from Acinetobacter baylyi bearing a similar extension despite significant difference in the genetic organization (Fig. S3A) (22). It was predicted that the CTR falls into random coils (Fig. S3B), and the Hfq 3D model (Fig. S3C), prepared using homology modeling, takes into consideration only the first 72 amino acids because this CTR has no homology to the structures submitted to the Protein Data Bank. This makes the CTR of A. baumannii unique and different from the previously studied CTR of E. coli and V. cholerae Hfq (24–26). To ensure that A. baumannii indeed expressed the abnormally long Hfq protein, MALDI-TOF MS–based analysis was carried out. The Hfq protein was confidently identified from a mixture of total proteins with two different peptides (Mowse score: Peptide 1 = 39, Peptide 2 = 52). Furthermore, mass accuracy in conjunction with Mr was used to attain high-confidence identification (Fig. S4).

The C terminus of Hfq is required for better sRNA interaction

To investigate the functional importance of the C terminus in RNA chaperoning, truncated versions of recombinant Hfq protein were expressed and purified for RNA interaction studies. Hfq66 (66 amino acids) contained only the core Sm domain; Hfq72 (72 amino acids) consisted of the residues that align with the Protein Data Bank template, P. aeruginosa Hfq; Hfq92 (92 amino acids) was a truncation that had the mean length of E. coli (102 amino acids) and P. aeruginosa Hfq (82 amino acids) with a very short stretch of glycine-rich repeats (Fig. S5A). Hfq168 represents the full-length WT version of A. baumannii Hfq.

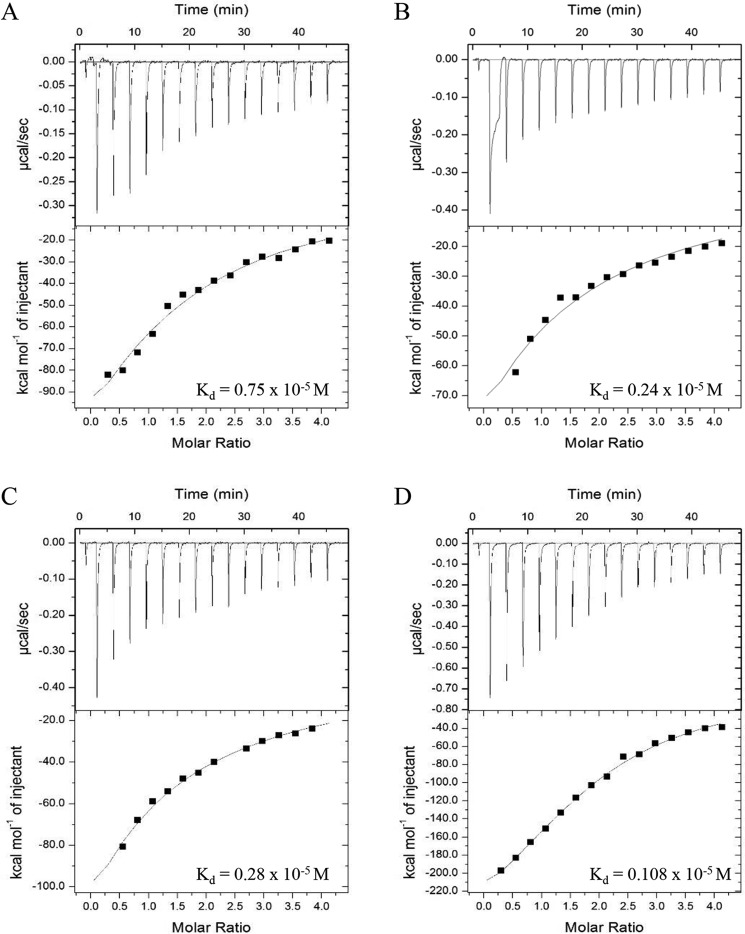

An electrophoretic mobility shift assay was carried out to assess the in vitro RNA-binding activity of Hfq. The recombinant Hfq formed complexes with the E. coli small RNA (DsrA and MicA) and the A. baumannii sRNA (AbsR25), as shown by retardation profiles of the sRNA obtained after staining the gel with SYBR Green II dye (Fig. 1, A–C). BSA was used as a negative control, and no binding was observed between sRNA and BSA. Similarly, no binding was observed between Hfq and randomly selected DNA molecules (Fig. S5B). Quantitative in vitro RNA–protein interactions were studied by isothermal calorimetery (ITC). For binding studies, AbsR25 sRNA was selected, as it has already been established as a trans-acting sRNA in A. baumannii (10). Because AbsR25 interacts with Hfq (as seen in a gel retardation assay), we tried to assess its interaction with the truncated variants of Hfq. The AbsR25 small RNA was titrated into purified Hfq variants, and the dissociation constant (Kd) values were determined (Fig. 2). Although all of the variants could bind to AbsR25, the binding affinity of Hfq168 was highest, followed by Hfq72 and Hfq92. Hfq66 had the least binding affinity toward AbsR25 small RNA (Fig. 2). This significance of CTR and its dynamics with sRNA were missed in the report on A. baylyi Hfq and a very recent report on A. baumannii Hfq (22, 27).

Figure 1.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay to assess Hfq and sRNA interaction. In vitro transcripts of E. coli sRNAs MicA (A) and DsrA (B) and A. baumannii sRNA, AbsR25 (C), at a fixed concentration of 2 pmol, were incubated with increasing concentrations of Hfq ranging from 0 to 25 pmol, for complex formation (marked by arrowheads). Lane i, sRNA alone; lane ii, sRNA + BSA; lanes iii–vii, sRNA + 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 pmol of Hfq protein, respectively.

Figure 2.

ITC-based interaction between sRNA, AbsR25 and Hfq truncations. 1 μm protein samples were titrated with 25 μm AbsR25 over a series of injections, and binding affinities (dissociation constant, Kd) were determined for Hfq66 (A), Hfq72 (B), Hfq92 (C), and Hfq168 (D).

Truncated Hfq proteins maintain their secondary structure over a range of temperature

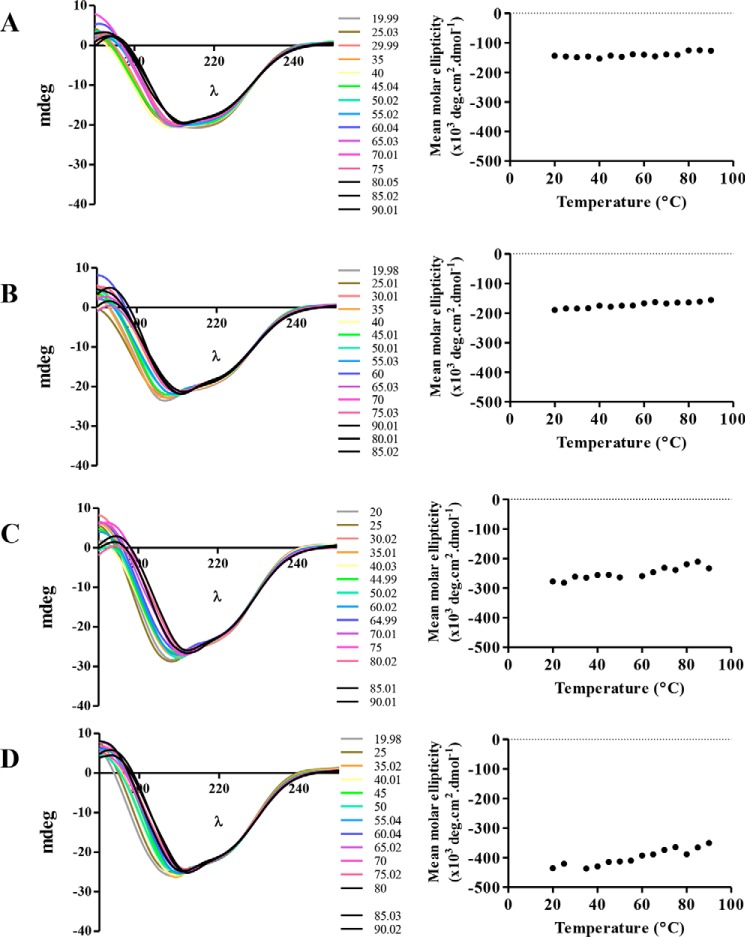

The Hfq protein is thermostable and retains its secondary structure even at high temperatures (28). To assess whether the C terminus was an important factor in determining this thermostability, we compared the CD spectra of the truncated proteins over a range of temperatures. Despite previous reports on C terminus–dependent stability (29), our results showed that all of the truncations of Hfq maintained their secondary structure, as there was little change in the spectra at increasing temperatures, and the mean molar ellipticity at 208 nm remained fairly constant for all of the truncated versions (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Analysis of secondary structure of Hfq truncations. The secondary structure of Hfq truncations was studied by assessing the CD spectra of the purified proteins at various temperatures. The CD spectra of Hfq66 (A), Hfq72 (B), Hfq92 (C), and Hfq168 (D) and corresponding molar ellipticity at 208 nm (over a range of temperatures) indicate that the truncations of Hfq are thermostable, similar to the full-length protein.

Hfq is required for growth and stress tolerance with the C terminus being indispensable

Considering the importance of CTR in RNA binding and the already reported role of Hfq-sRNA–based regulation in the physiology of other Gram-negative bacteria, we hypothesized that the CTR would also be important for normal physiological processes of A. baumannii (29). An hfq deletion mutant of A. baumannii was constructed using a homologous recombination-based approach (Fig. S6) (30). The deletion of hfq in A. baumannii (Δhfq) was complemented by plasmid-borne expression of different variants of hfq from the native promoter. The expression of the variants of Hfq protein was determined to be similar by Western blotting (Fig. S7).

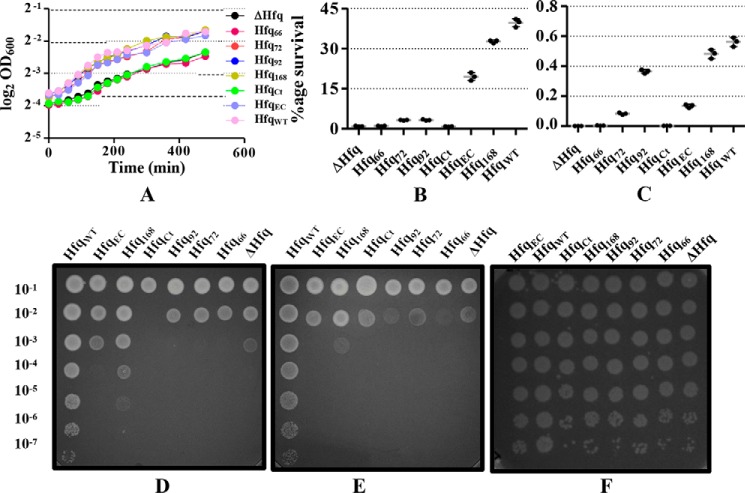

The loss of hfq in A. baumannii resulted in stunted growth as compared with the WT cells (Fig. 4A). Plasmid-borne expression of full-length Hfq (Hfq168) could complement the growth defect very well, but Hfq66 and HfqCt could not (Fig. 4A). There was a marked difference in the length of the lag phase and the final optical density. Other constructs, Hfq72, Hfq92, and HfqEC, had an almost identical growth profile, which was close, at best, to the WT- or the Hfq168-complemented phenotype (mean differences were not significant, as determined by Tukey's test). This observation probably explains why previous studies missed studying the importance of this CTR in the physiology of A. baumannii (22, 27).

Figure 4.

The effect of Hfq deletion and subsequent complementation, by constructs carrying varying lengths of C terminus, on physiology of A. baumannii. A, the growth profile of all the strains. The bacterial strains were grown at 37 °C with 200-rpm shaking, and the growth was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 600 nm. Each point represents the mean of triplicates with S.D. shown as error bars. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA, and p value was 0.0014. Tukey's test was used as a post hoc test to determine statistical significance of all pairs of data. B, effect of Hfq deletion and the presence of the C terminus on oxidative stress tolerance. The actively growing cells were briefly exposed to methyl viologen, and surviving cells were determined. The percentage survival was determined with respect to the untreated control. Each bar represents the mean of triplicates, with the error bar representing the S.D. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA, and p value was <0.0001. Tukey's test was used as a post hoc test to determine the statistical significance of all pairs of data. C, effect of Hfq deletion and the presence of the C terminus on thermal stress tolerance. The actively growing cells were briefly exposed to 55 °C, and surviving cells were determined. The percentage survival was determined with respect to the untreated control. Each bar represents the mean of triplicates with the error bar representing the S.D. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA, and p value was <0.0001. Tukey's test was used as a post hoc test to determine the statistical significance of all pairs of data. D, effect of Hfq deletion and presence of C terminus on acid stress tolerance. Overnight-grown cells were diluted in fresh LB and spotted on a plate containing LB agar at pH 5. The plate was incubated overnight at 37 °C, and the growth was compared with the control plate (F, containing LB at pH 7). E, effect of Hfq deletion and the presence of C terminus on osmotic stress tolerance. Overnight-grown cells were diluted in fresh LB and spotted on a plate containing LB agar supplemented with 2% NaCl. The plate was incubated overnight at 37 °C, and the growth was compared with the control plate (F, containing LB agar).

Because small RNA are involved in cellular adaptation to environmental stress, Hfq is intricately involved as well (29). To validate this claim, the cells were subjected to oxidative, thermal, acidic, and osmotic stress by using various physical and chemical agents.

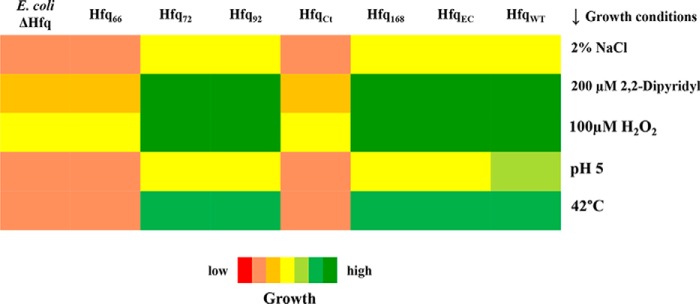

The WT cells had a better survival rate after a brief exposure to methyl viologen, an oxidizing agent, than the cells lacking hfq (Fig. 4B). The importance of CTR was highlighted by the fact that only the full-length Hfq expressed in trans could complement the deficit in oxidative stress adaptation. The E. coli Hfq could also complement the loss of hfq in this case, but only up to a limited extent. Similar observations were made in the case of thermal stress tolerance (Fig. 4C), as the percentage survival of WT cells was about 5 times higher than the hfq-debilitated cells after a brief heat shock. The impact of Hfq on acidic and osmotic stress tolerance was assessed by spotting serial dilutions of overnight cultures of A. baumannii cells onto LB agar plates at pH 5 and plates supplemented with 2% NaCl. The growth of A. baumannii cells at pH 5 (Fig. 4D) was reminiscent of the pattern seen in oxidative and thermal stress tolerance. The WT cells and the cells complemented with full-length Hfq could adapt to the stress and grew well in contrast to the cells expressing Hfq without the CTR. However, the same could not be concluded from the growth on NaCl (Fig. 4E), as no clear results were obtained. Unsurprisingly, the A. baumannii Hfq, except for the Hfq66 truncation, could complement the loss of hfq in E. coli as well (Fig. 5 and Fig. S7). This supports our hypothesis that the evolution of Hfq probably followed different routes in E. coli and A. baumannii.

Figure 5.

Complementation of E. coli Δhfq with different constructs of A. baumannii Hfq. Growth of E. coli cells, complemented with variants of Hfq, under different conditions (shown on the right) has been represented as varying colors ranging from red (low growth) to green (increased growth).

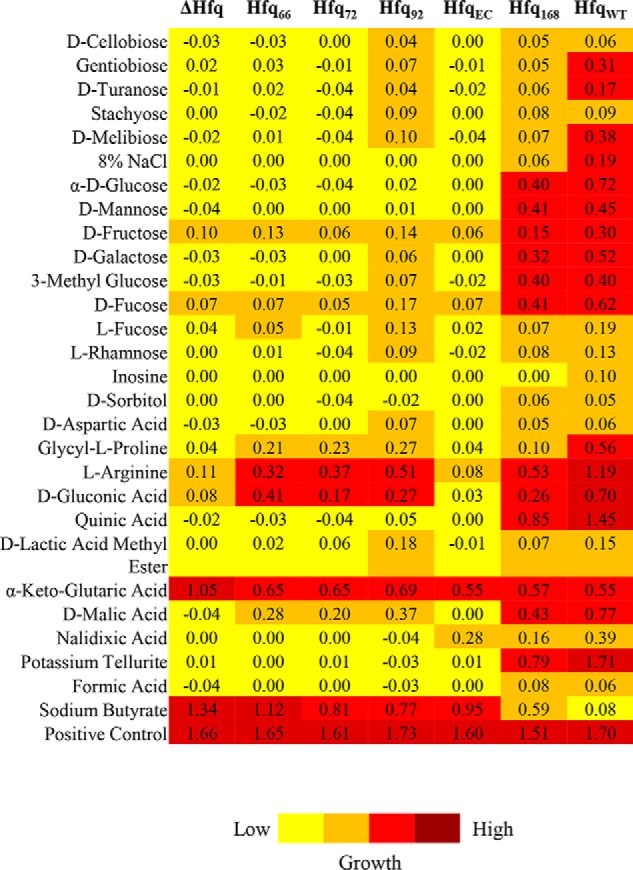

The presence of the C terminus is important for functional Hfq in carbon metabolism

The impact of Hfq and the requirement of CTR for a normal growth profile of A. baumannii led us to suspect its role in adaptation to carbon sources. A panel of various carbon sources including sugars, sugar acids, organic acids, amino acids, nucleosides, and a few stress-causing agents is available in a 96-well format in the BIOLOG GEN III microplatesTM (Biolog Inc.) (Table S2). It was observed that the cells lacking hfq were deficient in the metabolism of various carbon sources, despite similar growth of all of the cells in the control wells (Fig. 6). The inability of the hfq deletion mutant to metabolize certain substrates hints at the involvement of an Hfq-dependent sRNA-based switchover mechanism that helps the bacterium to utilize alternate sources of carbon (31). Importantly, a few of these substrates, including glucose, galactose, and mannose, were not metabolized by cells expressing truncated Hfq, suggesting that A. baumannii, under stress, employs sRNA to regulate metabolism of these substrates. It was also interesting to note that the cells expressing Hfq92 could utilize certain substrates like fucose, rhamnose, and stachyose (Fig. 6), but the cells expressing a similarly sized E. coli Hfq (but lacking the repeats) could not, highlighting the importance of glycine-rich repeats. Because Acinetobacter spp. have been historically known to be involved in bioremediation and biotransformation, this unusual structure of C terminus might be assisting sRNA–mRNA interactions involved in metabolism of these substrates (32–34).

Figure 6.

The effect of Hfq deletion and truncation on carbon metabolism in A. baumannii. The growth of hfq mutant and complemented strains was assayed on Gen III microplates and is depicted in varying colors ranging from low growth (yellow) to increased growth (red).

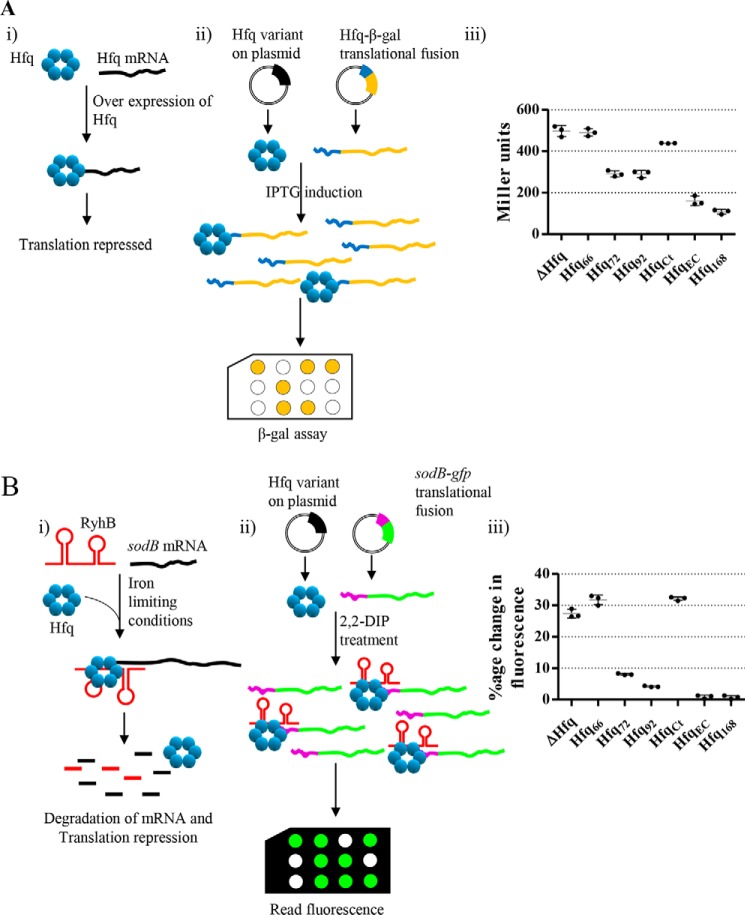

The C terminus is required for Hfq auto-regulation and sRNA-based regulation

It has been reported previously that the core Sm domain of E. coli Hfq could bind to sRNA in vitro but was deficient in regulatory roles (35). We questioned whether the C terminus in A. baumannii was important for Hfq to fulfill its regulatory roles. Hfq auto-regulates its expression by binding to its mRNA, resulting in a feedback inhibition loop (Fig. 7A (i)). The truncated versions of Hfq and translational fusion of hfq-lacZ were co-expressed in E. coli Δhfq. The cells were induced with IPTG to express hfq-lacZ fusion and simulate conditions where Hfq is overexpressed (Fig. 7A (ii)). The ability of different variants of Hfq to auto-regulate the expression of Hfq was measured as the ability to repress the activity of β-gal. It was observed that the Hfq variants deficient in C terminus were deficient in auto-regulation (Fig. 7A (iii)). Although some degree of auto-regulation was observed in the case of Hfq72 and Hfq92 (the difference between the two was not statistically significant), it was not as high as in the WT A. baumannii Hfq (Hfq168) (p < 0.001).

Figure 7.

Role of C terminus in maintaining regulatory functions of Hfq. A, auto-regulation of Hfq. i, the general scheme of auto-regulatory effect of Hfq on its own mRNA. To control the expression of hfq, the Hfq binds to its mRNA and represses the translation. ii, the assay design for studying auto-regulation. The various Hfq constructs were co-expressed in E. coli Δhfq along with an Hfq-lacZ translational fusion. The expression of Hfq-lacZ fusion was induced by the addition of IPTG, and the expression levels were determined by an ortho-nitrophenyl-β-galactoside–based β-gal assay. iii, β-gal activity was expressed as Miller units and compared. B, ribo-regulation of sodB mRNA. i, general scheme of RyhB-sodB regulation. Under iron-limiting conditions, RyhB binds to sodB mRNA, assisted by Hfq, and causes translational repression of sodB. ii, the various Hfq constructs were co-expressed in E. coli Δhfq along with an sodB-gfq translational fusion carrying the 5′-UTR of the A. baumannii sodB gene. Iron-deficient conditions were created by the addition of 2,2-dipyridyl, and the expression of sodB-gfp fusion was determined by measuring fluorescence of the cells. iii, percentage change in cellular fluorescence upon the addition of 2,2-dipyridyl as compared with normal conditions was determined. In both A (iii) and B (iii), each bar represents the mean of three experiments, and the error bars represent S.D. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA, and p value was <0.0001. Tukey's test was used as a post hoc test to determine the statistical significance of all pairs of data.

Because the C terminus was deemed important for auto-regulation of hfq expression, we proceeded to assess whether it was important for small RNA-based regulation as well. RyhB, an E. coli small RNA, negatively regulates the expression of sodB, when it is overexpressed, by binding to its 5′-UTR (Fig. 7B (i)) (36). This interaction is facilitated by Hfq, and the absence of Hfq abolishes this regulatory control, leading to uncontrolled expression of sodB. A translational fusion between 5′-UTR of A. baumannii sodB and GFP was co-expressed along with Hfq variants in E. coli Δhfq. We observed a lower relative change in GFP fluorescence in cells expressing full-length Hfq than in the Hfq-deficient cells (Fig. 7B (iii)), indicating the participation of A. baumannii Hfq in the RyhB-sodB regulatory circuit. The increase in GFP fluorescence in the case of Hfq168 was five times lower than that of Hfq72 and Hfq92 (p < 0.01), indicating that the CTR is required for efficient ribo-regulation. Because auto-regulation and ribo-regulation are dependent on successful RNA–Hfq interaction, these processes were affected, similar to the in vitro sRNA binding, when CTR was removed from Hfq. However, the inability of Hfq72 and Hfq92 to participate in auto- and ribo-regulation, despite very similar sRNA binding, could be explained by unavailability of critical acidic residues at the C-terminal tip of the Hfq (37). The C-terminal tip of Hfq168 has similar acidic residues (Fig. S1), which account for successful auto- and ribo-regulation by this variant in an E. coli genetic background.

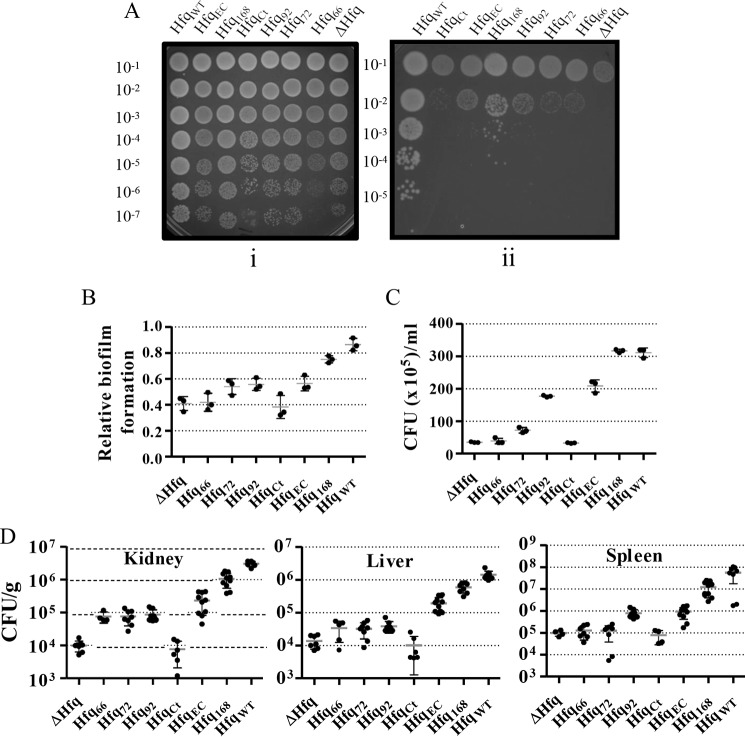

The C terminus is important for virulence

Because it is a clinically relevant bacterium, virulence mechanisms of A. baumannii are of great interest. We studied the role of Hfq in virulence of A. baumannii in terms of resistance to desiccation, biofilm formation, adherence to eukaryotic cell membranes, organ load in infected animal models, and antibiotic resistance, all of which have led to its success as a pathogen.

In an in vitro simulation of the hospital conditions, the A. baumannii cultures were allowed to dry in a polystyrene microtiter plate. The cells were revived by adding fresh medium, and the surviving population was determined by spotting the dilutions on an LB agar plate. It was clear that Hfq is a vital factor for survival under desiccation (Fig. 8A), as the deletion mutant as well as the cells expressing Hfq devoid of CTR had a limited revival. The revival of cells expressing the full-length Hfq (Hfq168) proves that full-length Hfq with the CTR is necessary for rescue of hfq-debilitated cells from desiccation.

Figure 8.

Importance of C terminus for virulence and virulence factors. A, desiccation assay. Actively growing A. baumannii cells were desiccated in a polystyrene 96-well plate at 25 °C and 40% relative humidity. After 60 h, the desiccated cells were resuspended in LB broth, and dilutions were spotted on LB agar plates (ii). Serial dilutions of cells before the desiccation were also spotted on a control plate (i). B, microtiter plate biofilm assay. Actively growing cells of A. baumannii were added to wells of a microtiter plate and incubated for 48 h at 30 °C, and the optical density was read at 600 nm. The wells were thoroughly washed, stained with fresh crystal violet, and washed again. The stained biomass was dissolved in methanol and quantified by measuring optical density at 575 nm. Relative biofilm formation was determined by calculating the ratio of A575 and A600. Each bar represents the mean of three experiments, and the error bars represent S.D. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA, and the p value was <0.0001. Tuckey's test was used as a post hoc test to determine the statistical significance of all pairs of data. C, adhesion of A. baumannii cells to the human embryonic kidney cells (HEK 293). The A. baumannii cells were incubated with the HEK 293 cells, at a multiplicity of infection of 100, for 1 h. The cells were subsequently washed, and their dilutions were spread on LB agar plates to determine the number of cells adhering to the eukaryotic cell membrane. Each bar represents the mean of three experiments, and the error bars represent S.D. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA, and the p value was <0.0001. Tuckey's test was used as a post hoc test to determine the statistical significance of all pairs of data. D, organ load of bacterial cells in mice infected with A. baumannii. The mice were rendered neutropenic by administration of cyclophosphamide and were subsequently infected by A. baumannii via intravenous injection. The mice were sacrificed after 24 h of infection, and the organ homogenates were prepared in PBS. Dilutions of the organ homogenates were spread on LB agar plates to determine the number of colony-forming units (CFU). Each point represents the mean of five different mice (n = 5), and the error bars represent S.D. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA, and the p value was <0.0001. Tukey's test was used as a post hoc test to determine the statistical significance of all pairs of data.

In vitro biofilm formation was assessed by a microtiter plate biofilm assay. The A. baumannii cells were allowed to form biofilms on polystyrene plates, which were stained with crystal violet and quantified. The cells devoid of Hfq were deficient in biofilm formation, an effect that could be complemented by the expression of full-length Hfq, Hfq168 (Fig. 8B). The expression of Hfq lacking the C terminus (Hfq66, Hfq72, Hfq92, and HfqEC) could not restore the biofilm on par with the biofilm formed in case of WT A. baumannii (p < 0.05).

To assess bacterial adhesion, the initiation of infection, A. baumannii cells were allowed to infect the HEK 293 cells, and the number of colony-forming units adhered to the membranes of the eukaryotic cells was determined. The deletion of hfq led to about 1 log reduction in adherence of A. baumannii cells (Fig. 8C). The importance of CTR in adhesion is obvious, as complementation by full-length Hfq restores the ability of A. baumannii to adhere to the eukaryotic cells. However, the cells expressing Hfq lacking the C terminus only partially restore it.

The virulence of A. baumannii was also studied in mouse models of infection. The mice were immunocompromised by administration of cyclophosphamide and injected intravenously with A. baumannii strains. The mice were sacrificed after 24 h of infection. Organ homogenates were made for kidney, liver, and spleen excised from the mice in PBS, and their dilutions were spread on LB agar plates to determine the bacterial load in these organs. Spleen appeared to be the most affected organ, followed by kidneys and liver. There was an average 3 log decreased bacterial load in case of hfq debilitated cells as compared with the WT cells (Fig. 8D). The bacterial load in the case of cells expressing Hfq lacking the CTR was higher than the deletion mutant but significantly less than the cells expressing full-length Hfq (p < 0.001). This again reflects the importance of full-length Hfq with an intact CTR.

The A. baumannii strains were examined for their antibiotic resistance. Being a rather sensitive strain, deletion of hfq in A. baumannii ATCC 17978 did not display a major change in resistance toward most of the drugs (38). However, a 2-fold reduction in the minimum inhibitory concentration of nalidixic acid and gentamycin was observed in A. baumannii Δhfq, a phenomenon that could be reversed only by the expression of full-length Hfq (Table 1). An interesting finding was the increase in resistance toward meropenem in A. baumannii Δhfq, which was not found in the WT cells as well as cells expressing the full-length Hfq. These observations hint at the involvement of sRNA in drug resistance in A. baumannii and the subsequent importance of Hfq. It is also evident that the CTR region is important to maintain this activity of Hfq. Taken together, these results reflect the importance of Hfq in governing the virulence of A. baumannii and validate the importance of CTR in these effects.

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations of antibacterials that showed variation in antibacterial potential against A. baumannii strains expressing a variant of Hfq

| Antibacterial agent | MICa |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔHfq | Hfq66 | Hfq72 | Hfq92 | Hfq168 | HfqEC | HfqCt | HfqWT | |

| μg/ml | ||||||||

| Nalidixic acid | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Gentamycin | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 4.8 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 4.8 |

| Meropenem | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 2 |

a Minimum inhibitory concentration.

Discussion

Overall, our experiments suggest that Hfq governs physiological properties like growth, stress tolerance, and virulence, implying that A. baumannii recruits small RNA for regulation of these processes. This also means that Hfq could in itself be considered a significant virulence factor. Therefore, further studies could be aimed at targeting Hfq as a plausible drug target. In addition, our experiments tried to demystify the presence and establish the importance of glycine-rich repeats at the C terminus. Most of the studies on the C terminus of Hfq have focused attention on residues that follow the Sm domain (from amino acid 66 onward) simply because other bacterial Hfq proteins do not have this glycine-rich CTR (26, 35, 39). Although it is known that Hfq66 is deficient in many physiological capabilities, there are conflicting reports about the importance of amino acids from 66 to 72. Therefore, we used both of the truncations in complementation experiments to rule out any problems due to experimental setup (14, 35, 39). Our observations indicate a marked difference in physiology of cells expressing Hfq66, Hfq72, and Hfq92 and confirm the importance of residues that lie beyond the Sm domain. The expression of these truncated variants of Hfq protein could not complement the loss of Hfq in A. baumannii, which was evident from various assays performed to compare the fitness of hfq deletion mutant and the cells complemented by expression of truncated variants of Hfq. Importantly, this variation in fitness was not due to suboptimal expression, as the expression of these truncated versions of Hfq was similar (Fig. S7).

Sequence analysis also suggests that Hfq might belong to a category of proteins bundled under an umbrella term, intrinsically unstructured proteins (40). Such proteins, despite varied origins, share certain characteristic features like (a) compositional bias, (b) the presence of small residues, (c) the presence of amino acids that provide flexibility, and (d) lower frequency of hydrophobic residues, all of which A. baumannii Hfq conforms to (40, 41). The fact that intrinsically unstructured proteins are highly regulated and placed under auto-regulatory control furthers the notion that Hfq belongs to this category of proteins (33). Intrinsically unstructured proteins are also found in the eukaryotic glycine-rich protein (GRP) family. The members of the GRP family have an RNA recognition domain at the N terminus and a glycine-rich domain at the C terminus (42). This glycine-rich tail imparts flexibility and assists these proteins in RNA binding and interaction with other protein partners. Coincidentally, a search for domains in the Hfq sequence reveals a distant relation of the CTR to the GRP family (Fig. S9). Considering the structure and function of Hfq, a C-terminal assist in homo- as well as heteromeric interactions seems to be an obvious advantage. Interestingly, GRPs have been reported to be central in RNA chaperoning and stress adaptation, much like Hfq (43). All of these observations may hint at an evolutionary relation between the prokaryotic and eukaryotic LSm proteins.

Unfortunately, at this time, the exact mechanistic details of the involvement of glycine-rich repeats are not known. It has recently been revealed that the length of the flexible tail between the core Sm domain and the acidic C-terminal residues is critical in determining the stringency in substrate specificity. The necessity of the interaction between the acidic residues on this tip and the basic residues in the core of Hfq is probably the reason why the CTR does not assume a fixed secondary structure but is rich in flexible residues like glycine. This elongated tail may have caused a relaxed specificity of substrate selection in Hfq, allowing better interaction with low-affinity sRNA. Theoretically, this immensely expands the substrate range of A. baumannii Hfq and might even allow yet-to-be-discovered interactions. Future studies aimed at structural characterization of A. baumannii Hfq may assist in elucidation of the role of the C terminus at the molecular level. Another avenue opened up by this study is the identification of sRNA involved in the regulation of physiological processes in A. baumannii. The defects brought about by hfq deletion point toward the involvement of small RNA in those respective properties, and careful experimentation and analysis could reveal these small RNA in the future.

Experimental procedures

Strains, plasmids, and culture conditions

The strains used in this study are listed in Table S3. Luria broth (LB) was used for culturing bacteria and was supplemented with 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol and 50 μg/ml (E. coli) or 15 μg/ml (A. baumannii) kanamycin, whenever required. Both E. coli and A. baumannii were routinely grown at 37 °C with 200-rpm agitation, unless specified. The plasmids and oligonucleotide primers used in this study are listed in Tables S4 and S5, respectively.

Bioinformatic analysis

The computational analysis has been detailed in supporting information section S1.

Recombinant DNA procedures

Hfq deletion mutant was generated by a homologous recombination–based approach using a kanamycin cassette flanked by a 125-bp region that flanks the hfq ORF. The deletion mutant was complemented by expressing various truncations of Hfq (generated by overlap extension PCR) from plasmid pWHN678. The truncated Hfq were also cloned in plasmid pET28 and expressed as hexahistidine derivatives in E. coli BL21 DE2 for nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid–based affinity purification.

All of the methods pertaining to recombinant DNA, gene deletion, complementation, cloning, and expression of Hfq protein are mentioned in supporting information section S2.

Mass spectrometric analysis using MALDI MS/MS

The cell lysates of WT and A. baumannii Δhfq were resolved by 15% Tricine-SDS-PAGE, and the band corresponding to Hfq was identified by MALDI MS/MS. The detailed methodology of MALDI MS/MS is explained in supporting information section S3.

Gel retardation assay

An electrophoretic mobility shift assay kit (Molecular Probes) was used for the gel retardation assay according to the manufacturer's instructions with some minor modifications. Small RNA AbsR25, DsrA, and MicA were incubated in binding buffer for 30 min in the presence of increasing amounts of Hfq. BSA was included as negative control. The complexes were resolved on 6% native gel. The gel was stained with SYBR Green and visualized using a Typhoon FLA scanner (GE Biosciences). The detailed methodology can be found in supporting information section S4.

ITC

AbsR25 transcript (20 μm) was titrated into 200 μl of 1 μm purified Hfq truncations in reaction buffer (20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 5% glycerol). Calorimetry was performed using MicroCal iTC200 (Malvern Instruments Ltd.) and is detailed in supporting information section S5.

Analysis of CD spectrum

The proteins were dialyzed in CD buffer (20 mm phosphate buffer, pH 8.0, 200 mm NH4Cl, 500 mm NaF, 2.5% glycerol). 1 mg/ml protein was assayed in a quartz cuvette of 0.1-cm path length. The CD analysis was done using a JASCO J-1000 spectrophotometer, and the data were analyzed using a dichroweb interface.

Complementation assays

Genetic complementation of E. coli and A. baumannii Δhfq was carried out by plasmid-borne expression of truncated Hfq. The levels of expression of truncated versions of Hfq proteins were assessed and ensured to be similar by Western blotting described in detail in supporting information section S6.

Growth of the strains was monitored by recording the optical density of the culture in Luria broth over time. The utilization of various carbon sources was assessed by using the Biolog bacterial identification system. The strains were grown in the biology plate containing different carbon sources, and the growth was determined by the spectrophotometric measurement of color produced by tetrazolium dye.

Thermal stress assessment was done by exposing the actively growing cells of A. baumannii to 65 °C for 30 min. The surviving population was determined by spreading the cells on LB plates. In the case of E. coli, dilutions of the overnight-grown cells were spotted on LB agar plates and incubated at 42 °C.

Osmotic, nutritive, and acid stress were simulated by the addition of 2% NaCl (w/v), 200 μm 2,2-dipyridyl (2,2-DIP; iron chelator), and agar plates made of LB at pH 5. Serial dilutions of the overnight-grown cells were spotted on these modified LB agar plates and incubated overnight at 37 °C.

A. baumannii cells were exposed to oxidative stress by the addition of 5 mm methyl viologen to the actively growing cells for 30 min. The surviving population was determined by spreading the cells on LB agar plates. In the case of E. coli, dilutions of overnight culture were spotted on LB agar containing 100 μm H2O2.

For the desiccation resistance assay, the overnight culture of A. baumannii cells was diluted in fresh LB, and 10 μl of the suspension was taken in a well of a polystyrene 96-well plate and allowed to dry at 25 °C with 40% relative humidity for 48 h. The cells were subsequently revived by the addition of fresh LB broth, and the surviving population was determined by spreading the suspension on LB agar plates.

In vitro biofilm formation was studied by growing A. baumannii cells in borosilicate tubes. The tubes were incubated for 48 h at 30 °C and washed in PBS, and the resulting biofilm was stained with freshly prepared 1% crystal violet. The tubes were again kept for 30 min at room temperature. The tubes were finally washed in PBS, and the stain was dissolved in methanol. The A575 was determined as a measure of biofilm formed. Antimicrobial susceptibility assays were carried out using the broth dilution method in Mueller Hinton broth as per Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines.

Bacterial adhesion was determined on HEK 293 cells in 24-well plates. The mammalian cells were incubated with the bacterial cells at a multiplicity of infection of 100 for 1 h. The wells were carefully washed with PBS multiple times, and the cells were subsequently scraped off. Dilutions of the scraped suspension were spread on LB agar plates to determine the adhered bacteria.

All of the complementation assays to determine the ability of hfq truncations to complement the gene deletion have been described in detail in supporting information section S7.

Auto-regulation of Hfq

Plasmid pR131 contains an hfq-lacZ translational fusion. The plasmid was transformed into E. coli Δhfq. The plasmids carrying the complementing truncations of hfq were individually co-transformed along with pR131. The cells were grown until exponential phase, and overexpression of hfq-lacZ was induced by the addition of 2 mm IPTG for 30 min. 1 ml of culture was withdrawn, and its A600 was measured. The cells were collected by centrifugation, and the β-gal activity was determined by a classical ortho-nitrophenyl-β-galactoside–based assay. A detailed methodology can be found in supporting information section S8.

Ribo-regulation by Hfq

sodB-gfp translational fusion was constructed in plasmid pRPT21. The plasmid was transformed into E. coli Δhfq, and the plasmids expressing the hfq truncations were individually co-transformed. The cells were grown to exponential phase and were treated with 2,2-DIP for 30 min to simulate iron-deficient conditions that lead to overexpression of SodB. The relative change in fluorescence of the cells was measured before and after the 2,2-DIP treatment by measuring the fluorescence at excitation of 480 nm and emission of 519 nm. The method is explained in detail in supporting information section S9.

Animal studies

All protocols pertaining to animal studies were approved by the institutional animal ethics committee following the CPCSEA (Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals) guidelines. A neutropenic mouse model for A. baumannii infection was prepared using 8-week-old female BALB/c mice, as described earlier (44). The details are given in supporting information section S10.

Statistical analysis

All of the data were presented as mean values ± S.D. One-way ANOVA was used to assess the randomness of the data and a measure of overall statistical significance between the different groups. Tukey's test was used as a post hoc test to determine statistical significance in the means of all the possible pairs of data. The graphs were drawn, and the statistical significance was determined using GraphPad Prism version 5 software. Significance (p) values are indicated as follows: *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001; ****, p ≤ 0.0001.

Author contributions

A. S. and R. P. conceptualization; A. S. data curation; A. S. and R. S. software; A. S. and R. P. formal analysis; A. S. and V. D. validation; A. S., V. D., R. S., K. D., V. K. G., J. A., T. B., A. V., K. A., M. S., and R. P. methodology; A. S. and R. P. writing-original draft; A. S., K. A., and R. P. writing-review and editing; A. S., V. D., and R. P. investigation; R. P. supervision; R. P. resources; R. P. funding acquisition; A. S. and R. P. visualization; R. P. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Prof. Udo Bläsi (Max F. Perutz Laboratories, Vienna Biocenter, Austria), Prof. Raghavan Varadarajan (IISc Bangalore, India), Prof. Naveen Kumar Navani (IIT Roorkee), and Prof. Brian Davies (University of Texas, Austin, TX) for various vital plasmids used in this study. We also extend heartfelt thanks to Prof. Partha Roy and members of his laboratory for animal cell lines. We are extremely thankful to Dr. Susan Gottesman and her group at NCI, National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD) for providing the anti-Hfq antibody as a kind gift. We are also thankful to Dr. Rahul Das (IISER Kolkata, India) and Madhusudhanarao Katiki and Pranav Kumar (IIT Roorkee, India) for immense help with biophysical studies and the entire Molecular Bacteriology and Chemical Genetics Laboratory (IIT Roorkee) for extensive support during the animal experiments. We especially thank Dr. Naveen Kumar Navani (IIT Roorkee) for suggestions and input during the experiments and critical comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by Department of Biotechnology, Government of India, Grant BT/PR11943/MED/29/874/2014; Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India, Ph.D. support fellowships (to A. S., R. S., T. B., and A. V.); a grant from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India (to V. D.); and a grant from the Indian Council of Medical Research (to J. A.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

This article contains Tables S1–S5, Figs. S1–S9, and sections S1–S10.

- sRNA

- small RNA

- LSm

- Sm-like

- CTR

- C-terminal region

- ITC

- isothermal calorimetery

- IPTG

- isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside

- β-gal

- β-galactosidase

- GRP

- glycine-rich protein

- LB

- Luria broth

- Tricine

- N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine

- 2,2-DIP

- 2,2-dipyridyl

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

References

- 1. Peleg A. Y., Seifert H., and Paterson D. L. (2008) Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21, 538–582 10.1128/CMR.00058-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bigot S., and Suzana S. P. (2017) The influence of two-partner secretion systems on the virulence of Acinetobacter baumannii. Virulence. 8, 653–654 10.1080/21505594.2017.1283465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kawamura-Sato K., Wachino J., Kondo T., Ito H., and Arakawa Y. (2010) Correlation between reduced susceptibility to disinfectants and multidrug resistance among clinical isolates of Acinetobacter species. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65, 1975–1983 10.1093/jac/dkq227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mussi M. A., Gaddy J. A., Cabruja M., Arivett B. A., Viale A. M., Rasia R., and Actis L. A. (2010) The opportunistic human pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii senses and responds to light. J. Bacteriol. 192, 6336–6345 10.1128/JB.00917-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Poulikakos P., Tansarli G. S., and Falagas M. E. (2014) Combination antibiotic treatment versus monotherapy for multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant, and pandrug-resistant Acinetobacter infections: a systematic review. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 33, 1675–1685 10.1007/s10096-014-2124-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abbott A. (2005) Medics braced for fresh superbug. Nature 436, 758–758 10.1038/436758a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gordon N. C., and Wareham D. W. (2010) Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: mechanisms of virulence and resistance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 35, 219–226 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee C.-R., Lee J. H., Park M., Park K. S., Bae I. K., Kim Y. B., Cha C.-J., Jeong B. C., and Lee S. H. (2017) Biology of Acinetobacter baumannii: pathogenesis, antibiotic resistance mechanisms, and prospective treatment options. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Papenfort K., and Vogel J. (2014) Small RNA functions in carbon metabolism and virulence of enteric pathogens. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 4, 91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sharma R., Arya S., Patil S. D., Sharma A., Jain P. K., Navani N. K., and Pathania R. (2014) Identification of novel regulatory small RNAs in Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS One 9, e93833 10.1371/journal.pone.0093833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sharma A., Sharma R., Bhattacharyya T., Bhando T., and Pathania R. (2017) Fosfomycin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii is mediated by efflux through a major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporter—AbaF. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72, 68–74 10.1093/jac/dkw382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Svensson S. L., and Sharma C. M. (2016) Small RNAs in bacterial virulence and communication. Microbiol. Spectr. 4 10.1128/microbiolspec.VMBF-0028-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vogel J., and Luisi B. F. (2011) Hfq and its constellation of RNA. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 578–589 10.1038/nrmicro2615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Updegrove T. B., Zhang A., and Storz G. (2016) Hfq: the flexible RNA matchmaker. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 30, 133–138 10.1016/j.mib.2016.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sobrero P., and Valverde C. (2012) The bacterial protein Hfq: much more than a mere RNA-binding factor. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 38, 276–299 10.3109/1040841X.2012.664540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tsui H. C., Leung H. C., and Winkler M. E. (1994) Characterization of broadly pleiotropic phenotypes caused by an hfq insertion mutation in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Microbiol. 13, 35–49 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00400.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ding Y., Davis B. M., and Waldor M. K. (2004) Hfq is essential for Vibrio cholerae virulence and downregulates σ expression. Mol. Microbiol. 53, 345–354 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04142.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sonnleitner E., Hagens S., Rosenau F., Wilhelm S., Habel A., Jäger K. E., and Bläsi U. (2003) Reduced virulence of a hfq mutant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa O1. Microb. Pathog. 35, 217–228 10.1016/S0882-4010(03)00149-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sittka A., Pfeiffer V., Tedin K., and Vogel J. (2007) The RNA chaperone Hfq is essential for the virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 63, 193–217 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05489.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chiang M.-K., Lu M.-C., Liu L.-C., Lin C.-T., and Lai Y.-C. (2011) Impact of Hfq on global gene expression and virulence in Klebsiella pneumoniae. PLoS One 6, e22248 10.1371/journal.pone.0022248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Amin S. V., Roberts J. T., Patterson D. G., Coley A. B., Allred J. A., Denner J. M., Johnson J. P., Mullen G. E., O'Neal T. K., Smith J. T., Cardin S. E., Carr H. T., Carr S. L., Cowart H. E., DaCosta D. H., et al. (2016) Novel small RNA (sRNA) landscape of the starvation-stress response transcriptome of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. RNA Biol. 13, 331–342 10.1080/15476286.2016.1144010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schilling D., and Gerischer U. (2009) The Acinetobacter baylyi hfq gene encodes a large protein with an unusual C terminus. J. Bacteriol. 191, 5553–5562 10.1128/JB.00490-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang A., Schu D. J., Tjaden B. C., Storz G., and Gottesman S. (2013) Mutations in interaction surfaces differentially impact E. coli Hfq association with small RNAs and their mRNA targets. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 3678–3697 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beich-Frandsen M., Večerek B., Konarev P. V., Sjöblom B., Kloiber K., Hämmerle H., Rajkowitsch L., Miles A. J., Kontaxis G., Wallace B. A., Svergun D. I., Konrat R., Bläsi U., and Djinovic-Carugo K. (2011) Structural insights into the dynamics and function of the C-terminus of the E. coli RNA chaperone Hfq. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 4900–4915 10.1093/nar/gkq1346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fortas E., Piccirilli F., Malabirade A., Militello V., Trépout S., Marco S., Taghbalout A., and Arluison V. (2015) New insight into the structure and function of Hfq C-terminus. Biosci. Rep. 35, e00190 10.1042/BSR20140128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vincent H. A., Henderson C. A., Ragan T. J., Garza-Garcia A., Cary P. D., Gowers D. M., Malfois M., Driscoll P. C., Sobott F., and Callaghan A. J. (2012) Characterization of Vibrio cholerae Hfq provides novel insights into the role of the Hfq C-terminal region. J. Mol. Biol. 420, 56–69 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.03.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kuo H.-Y., Chao H.-H., Liao P.-C., Hsu L., Chang K.-C., Tung C.-H., Chen C.-H., and Liou M.-L. (2017) Functional characterization of Acinetobacter baumannii lacking the RNA chaperone Hfq. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2068 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arluison V., Folichon M., Marco S., Derreumaux P., Pellegrini O., Seguin J., Hajnsdorf E., and Regnier P. (2004) The C-terminal domain of Escherichia coli Hfq increases the stability of the hexamer. Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 1258–1265 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04026.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chao Y., and Vogel J. (2010) The role of Hfq in bacterial pathogens. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13, 24–33 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tucker A. T., Nowicki E. M., Boll J. M., Knauf G. A., Burdis N. C., Trent M. S., and Davies B. W. (2014) Defining gene-phenotype relationships in Acinetobacter baumannii through one-step chromosomal gene inactivation. MBio 5, e01313–14 10.1128/mBio.01313-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peleg A. Y., de Breij A., Adams M. D., Cerqueira G. M., Mocali S., Galardini M., Nibbering P. H., Earl A. M., Ward D. V., Paterson D. L., Seifert H., and Dijkshoorn L. (2012) The success of Acinetobacter species: genetic, metabolic and virulence attributes. PLoS One 7, e46984 10.1371/journal.pone.0046984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Paisio C. E., Talano M. A., González P. S., Magallanes-Noguera C., Kurina-Sanz M., and Agostini E. (2016) Biotechnological tools to improve bioremediation of phenol by Acinetobacter sp. RTE1.4. Environ. Technol. 37, 2379–2390 10.1080/09593330.2016.1150352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hanson K. G., Nigam A., Kapadia M., and Desai A. J. (1997) Bioremediation of crude oil contamination with Acinetobacter sp. A3. Curr. Microbiol. 35, 191–193 10.1007/s002849900237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Desouky A.-E.-H. (2003) Acinetobacter: environmental and biotechnological applications. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2, 71–74 10.5897/AJB2003.000-1014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vecerek B., Rajkowitsch L., Sonnleitner E., Schroeder R., and Bläsi U. (2008) The C-terminal domain of Escherichia coli Hfq is required for regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 133–143 10.1093/nar/gkm985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Massé E., Vanderpool C. K., and Gottesman S. (2005) Effect of RyhB small RNA on global iron use in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 187, 6962–6971 10.1128/JB.187.20.6962-6971.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Santiago-Frangos A., Jeliazkov J. R., Gray J. J., and Woodson S. A. (2017) Acidic C-terminal domains autoregulate the RNA chaperone Hfq. Elife 6, e27049 10.7554/eLife.27049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Valentine S. C., Contreras D., Tan S., Real L. J., Chu S., and Xu H. H. (2008) Phenotypic and molecular characterization of Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates from nosocomial outbreaks in Los Angeles County, California. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46, 2499–2507 10.1128/JCM.00367-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Olsen A. S., Møller-Jensen J., Brennan R. G., and Valentin-Hansen P. (2010) C-terminally truncated derivatives of Escherichia coli Hfq are proficient in riboregulation. J. Mol. Biol. 404, 173–182 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.09.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dyson H. J., and Wright P. E. (2005) Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 197–208 10.1038/nrm1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rogelj B., Godin K. S., Shaw C. E., and Ule J. (2011) The functions of glycine rich regions in TDP-43, Fus and related RNA binding proteins. In RNA Binding Proteins (Zdravko Lorkovic, ed), pp. 1–17, Landes Bioscience and Springer Science Austin, TX [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sachetto-Martins G., Franco L. O., and de Oliveira D. E. (2000) Plant glycine-rich proteins: a family or just proteins with a common motif? Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1492, 1–14 10.1016/S0167-4781(00)00064-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim J. S., Park S. J., Kwak K. J., Kim Y. O., Kim J. Y., Song J., Jang B., Jung C. H., and Kang H. (2007) Cold shock domain proteins and glycine-rich RNA-binding proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana can promote the cold adaptation process in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 506–516 10.1093/nar/gkl1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. García-Quintanilla M., Caro-Vega J. M., Pulido M. R., Moreno-Martínez P., Pachón J., and McConnell M. J. (2016) Inhibition of LpxC increases antibiotic susceptibility in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 5076–5079 10.1128/AAC.00407-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.