Abstract

Solid‐state structures, based on a Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) search, show that there is a CαN/C′Ocis attraction in the torsional system OcisC′CαN of valine, causing a chirality chain. The Cα configuration controls the chirality of the rotation around the C′−Cα bond, which in turn induces a distortion of the planar unit CαC′(O)O to a flat asymmetric tetrahedron. Conformational “reactions” take place in an energy profile with respect to clockwise and counterclockwise rotation around the C′−Cα bond as well as stretching and flattening of the tetrahedron. The molecular property CαN/C′Ocis attraction of valine is maintained in its di‐ and tripeptides.

Keywords: amino acids, chirality, conformation, peptides, valine

Natural amino acids with their inherent molecular properties are the building blocks of proteins. Herein, we show that for valine, the chirality chain from the configuration at the Cα position through the torsional system Ocis−C′−Cα−N, leads to the distortion of the planar group CαC′(Ocis)Otrans to a flat tetrahedron.

A search in the Cambridge Structural Database for H3N−CH(iPr)−C′(O)O gave 68 hits, with 28 structures containing independent molecules. Thus, 105 cases are available for analysis (these are collected in Tables S1 and S2 in the Supporting Information). As these tables comprise up to 65 entries, truncated Table 1 and Table 2 are used in this Communication.

Table 1.

Zwitterionic valine structures.

| Entry | CSD symbol[a] | Chirality chain | Distances [Å] | Attraction CαN/C′O angles [°] | Comments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Config. Cα |

Ocis‐C′‐Cα‐N rotation angle ψ [°] |

Otrans‐C′‐Cα‐Ocis

pyramidal angle θ [°] |

Ocis−N | Ocis−C(iPr) | N‐Cα‐C′(O) | (iPr)C‐Cα‐C′(O) | |||

| 1 | LVALIN01(1) | L | −17.48 | −177.78 | 2.66 | 3.39 | 109.26 | 112.72 | enantiomer(1) |

| 4 | VALIDL03 | L | −23.31 | −179.09 | 2.67 | 3.33 | 110.02 | 112.47 | racemate[b] |

| 8 | LVALIN01(2) | L | −42.81 | −177.66 | 2.76 | 3.10 | 109.33 | 110.48 | enantiomer(2) |

| 12 | AHEJEC(1)[c] | D | 17.95 | 177.75 | 2.66 | 3.38 | 109.31 | 112.98 | enantiomer(1) |

| 18 | AHEJEC03(2)[c] | D | 43.99 | 177.82 | 2.75 | 3.09 | 109.23 | 110.74 | enantiomer(2) |

| 20 | OPEFUL[1] | L | −5.53 | −181.00 | 2.60 | 3.51 | 107.19 | 116.10 | +l‐valine⋅HCl adduct |

| 25 | GUQJUZ[1](2) | L | −20.39 | −177.28 | 2.64 | 3.30 | 107.90 | 112.64 | +valine⋅naphthalene‐ 1,5‐(SO3H)2 adduct |

| 30 | GOLVUY | L | −35.59 | −177.34 | 2.69 | 3.17 | 108.04 | 110.44 | +d‐n‐BuAA[d] |

| 40 | SONCED[c] | D | 25.84 | 179.48 | 2.68 | 3.31 | 109.52 | 112.63 | +l‐phenylalanine |

| average | −27.74 | −178.32 | 2.69 | 3.28 | 108.86 | 111.95 | |||

[a] Parenthesis () indicate independent molecules in the unit cell, whereas brackets [] differentiate between +NH3CH(iPr)COO− and +NH3CH(iPr)COOH. [b] Racemates given as l‐compounds. [c] For average calculation rotation angle and distortion angle are inverted. [d] AA=amino acid.

Table 2.

Valine zwitterions protonated at the carboxylic group by strong acids.

| Entry | CSD symbol[a] | Chirality chain | Distances [Å] | Attraction CαN/C′O angles [°] | Comments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Config. Cα |

Ocis‐C′‐Cα‐N rotation angle ψ [°] |

Otrans‐C′‐Cα‐Ocis

pyramidal angle θ [°] |

Ocis−N | Ocis−C(iPr) | N‐Cα‐C′(O) | (iPr)C‐Cα‐C′(O) | |||

| 1 | WIHQUA(1) | L | 1.77 | −182.10 | 2.66 | 2.66 | 107.24 | 111.77 | H2NbOF5 |

| 8 | VALHCL10 | L | −3.72 | −182.11 | 2.68 | 2.68 | 108.41 | 109.80 | HCl, H2O |

| 16 | TUZJIJ | L | −11.44 | −177.98 | 2.65 | 2.65 | 107.86 | 110.89 | TsOH, H2O |

| 24 | WIHQUA(2)[b] | L | −15.68 | −178.90 | 2.68 | 2.68 | 107.69 | 113.46 | H2NbOF5 |

| 32 | BANPOW(4) | L | −20.98 | −177.94 | 2.69 | 2.69 | 107.69 | 110.13 | HClO4 |

| 40 | DUMZOB | L | −25.00 | −179.10 | 2.71 | 2.71 | 107.07 | 113.47 | HCl, Bn ester |

| 48 | ROKBOI(2) | L | −32.49 | −179.22 | 2.76 | 2.76 | 108.63 | 109.72 | HNO3 |

| 56 | ESAPET01(1) | L | −14.91 | −179.54 | 2.65 | 2.65 | 110.26 | 112.59 | H2PbO3, 2HNO3, H2O |

| 65 | VALCAC | L | −35.46 | −179.94 | 2.67 | 2.67 | 105.99 | 110.48 | CaCl2(H2O) |

| average | −18.69 | −179.06 | 2.67 | 3.36 | 107.69 | 112.38 | |||

[a] Parenthesis () indicate independent molecules in the unit cell. [b] Racemates given as l‐compounds.

There are 40 structure determinations of valine in its zwitterionic form (see Table S1). Three representative examples of pure valine racemate and enantiomers are given at the beginning of Table 1. The valine enantiomers have two independent molecules in the unit cell, differentiated by parentheses. The second part of Table 1 contains zwitterionic valine structures in different environments, selected such that Table 1 does not exceed ten entries.

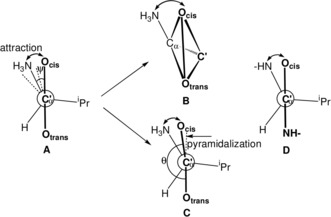

We determined the torsion angles ψ=Ocis−C′−Cα−N of the valine racemate (Table 1, entry 4) and enantiomers (entries 1 and 8). We differentiate the oxygen atoms of the carboxylic group as Ocis and Otrans according to their orientation with respect to the amino nitrogen atom (Figure 1 A). As the torsion angles ψ measure the rotation around the Cα−C′(O)O bond, we call them rotation angles. For l‐valine in enantiomers and racemates the rotation angles ψ are negative (Figure 1 A), for d‐valine they are positive. A four‐atom system such as Ocis−C′−Cα−N is chiral, unless the torsion angle ψ is 0 or 180°. According to the helicity rule of the CIP system,1 positive rotation angles result in (P)‐conformation and negative angles in (M)‐conformation.

Figure 1.

A) Rotation angles ψ=Ocis−C′−Cα−N in the zwitterionic racemate and enantiomers (dashed) of l‐valine (Table 1, entries 1, 4, 8), looking down the C′−Cα bond (symbol C′α). B) Distortion of the planar system CαC′(O)O to a chiral flat tetrahedron (exaggerated). C) Attraction CαN/C′O: bending of C′−Ocis towards Cα−NH3. D) Conformation of valine in di‐ and tripeptides.

The central carbon atom of the carboxylic group of valine is sp2‐hybridized. Thus, the unit CαC′(O)O should be planar and achiral. However, a deviation from planarity results in a flat tetrahedron, which is chiral, due to its four different corners C′, Cα, Ocis, and Otrans (Figure 1 B). A measure of its chirality is the torsion angle θ=Otrans−C′−Cα−Ocis. The torsion angles θ will be called pyramidalization angles. They determine the deviation of Ocis from the plane Otrans−C′−Cα (Figure 1 B and 1C) due to the attraction CαN/C′O (see below). The configuration of the flat tetrahedron will be specified by (R)/(S) according to the priority sequence Ocis>Otrans>C′>Cα of the CIP system.1 For valine in peptides the priority sequence is O>N>C′>Cα. The flat tetrahedron in Figure 1 B and 1C has (S)‐configuration. Thus, the complete stereochemistry of l‐valine in enantiomers and racemates is L(M)(S) and that of d‐valine is D(P)(R).

In the tables, all the hits of the CSD search are included irrespective of old/new, low/high quality, because each hit is an individual structure determination. Multiple analyses help to evaluate small effects such as tetrahedral distortions. For the relatively large pyramidalization angle θ=177.10° of AHEJEC03(2) (Table S1, entry 18), the deviation of Ocis from the plane Otrans−C′−Cα amounts to 0.021 Å. However, the following analysis will show that both the induction from the given chirality at Cα to the torsional system OcisC′CαN and from the torsional system to the pyramidalization of the planar group CαC′(O)O occurs with high diastereoselectivity.

The second part of Table 1 shows structures in which the valine zwitterion crystallizes together with l‐valine molecules protonated by strong acids or co‐crystallizes with natural and unnatural amino acids. In all cases the induction chain L→(−)→(−) is perfect. In the 40 cases of Table S1, there is one example in which the rotation angle ψ adopts a small positive value, inducing (P)‐configuration in the flat tetrahedron. Concerning the induction from the torsional system to the flat tetrahedron there are four exceptions (θ>−180°).

In entries 1–40 of Tables 1 and S1 the valine zwitterion is in completely different environments. Irrespective of the changing packing and hydrogen‐bond networks, a unique structural motif is common to all structures, the chiral induction chain. The given l/d‐chirality at the Cα position controls the arrangement of the torsional system OcisC′CαN in the narrow range from 3.49° to −53.26° of rotation angles ψ. The other 303° of the full circle are not occupied by sample points. The torsional system OcisC′CαN in turn induces the preferred (S)‐configuration in the flat tetrahedron with high selectivity.

Strong acids protonate valine at the carboxylic group to give salt‐like structures with the cation H3N‐CH(iPr)‐C′(O)OH+. In all the structures of Tables 2 and S2 (54 cases), protonation occurs on the Otrans atom except for HOSMEA (entry 54). In three cases, the Otrans centre is alkylated to give the methyl and benzyl esters (entries 39, 40, and 46). Protonation and alkylation differentiate Ocis and Otrans with respect to the lengths of the C′−O bonds. The C′−O bonds are much longer in the COH/R system compared to the C=O group.

The range of rotation angles ψ in Tables 2 and S2 from 1.77° to −43.91° is even a little narrower than in Tables 1 and S1. According to the chirality chain, the two slightly positive rotation angles in entries 1 and 2 induce positive pyramidal angles. The 49 negative rotation angles from entry 3 to entry 52 in the l‐valine series result in negative pyramidal angles (9 exceptions; θ>−180°). Thus, the results in Tables 2 and S2 corroborate the high selectivities in protonation as well as rotation and pyramidalization angles.

At the end of Table S2 (see the Supporting Information) eleven structures are listed in which valine zwitterions coordinate as ligands in metal complexes. The induction from the Cα position to the torsional system OcisC′CαN is perfect; from the torsional system to the flat tetrahedron there are two exception (θ>−180°).

In Table S1 (see the Supporting Information) there is one l‐Val with a positive rotation angle and Table S2 contains two l‐Val entries with slightly positive rotation angles. They are the positive parts of the range from −53.26° to 3.49°, which is well in agreement with the fact that the Cα configuration confers induction onto the torsional system OcisC′CαN. However, the chirality of the torsional system OcisC′CαN changes from (M) for −53.26–0° to (P) for 0–3.49°.

In the torsional system OcisC′CαN of the valine zwitterions, the Cα−NH3 bond is close to eclipsing the C′−Ocis bond, indicating an attraction Cα−NH3/C′−Ocis. This is evident in the small negative rotation angles ψ (average ψ=−27.74° in Table S1, ψ=−18.69° in Table S2, and average ψ=−22.13° in Tables S1 and S2, see the Supporting Information). We think the attraction is due to NH…Ocis hydrogen bonding.

The attraction Cα−NH3/C′−Ocis should manifest itself also in structural parameters like distances and bond angles. In the torsional system OcisC′CαN, proof for an attraction comes from the distances Ocis−N and Ocis−C(iPr) in Tables 1 and S1 and Tables 2 and S2 (columns 6 and 7; see the Supporting Information). Increasing the rotation angle ψ from 0 to −53° should increase the distances Ocis−N and decrease the distances Ocis−C(iPr) in the same way. However, excluding the outlier 2.48 Å (see Table S2, entry 13 in the Supporting Information), the interval of the distances Ocis−N spans only 0.2 Å from 2.60–2.82 Å, whereas the interval of the distances Ocis−C(iPr) overstretches 0.6 Å from 3.00–3.60 Å. This shows that the torsional system OcisC′CαN resists elongation of the distance Ocis−N by adjusting bond lengths and angles such as to keep the distance Ocis−N as constant as possible. As the van der Waals radii of O and N are 1.55 and 1.60 Å,2 the Ocis−N distances are far below the sum of the van der Waals radii, indicating an attractive interaction in the torsional system OcisC′CαN.

In columns 8 and 9 of Tables 1 and S1, the bond angles N‐Cα‐C′(O) and (iPr)C‐Cα‐C′(O) are compared. The N‐Cα‐C′(O) angles are generally below the tetrahedral angle (average 108.86°; see Table S1) and smaller than the (iPr)C‐Cα‐C′(O) angles, which are above the tetrahedral angle (average 111.95°). Tables 2, 2 and Tables S2 and S3 show the same trends. As the size of the isopropyl substituent could be a reason for the large angles (iPr)C‐Cα‐C′(O), we checked the 78 zwitterionic structures of alanine in the CSD. In alanine, Cα−NH3 and Cα−CH3 have similar sizes. The averages of the angles H3N‐Cα‐C′(O) and H3C‐Cα‐C′(O) in alanine are 109.70° and 111.44°,3 confirming the attraction Cα−NH3/C′−Ocis, which in turn is the reason for the chirality transfer from the Cα configuration to the torsional system OcisC′CαN.

Thus, distances and torsion as well as bond angles prove the attraction Cα−NH3/C′−Ocis, in which C′−Ocis and Cα−NH3 bend towards each other (Figure 1 C) in valine and also in alanine.

The 105 sample points of Tables S1 and S2 are shown in the histogram of Figure 2. l‐compounds crowd in the lower right quadrant. In Figure 2 the d‐compounds are inverted to l‐compounds. Exceptions appear in the lower left quadrant. The best‐fit line of the 102 compounds with negative rotation angles indicates a good correlation of rotation and pyramidalization angles (step 2 of the chirality chain). The best‐fit line is additional proof for the attraction Cα−NH3/C′−Ocis. It shows that the more the Ocis centre is removed from the perpendicular plane OtransC′Cα in Figure 1 C, the larger the torsion angle ψ.

Figure 2.

Histogram of the correlation of rotation angles (ordinate) and pyramidalization angles (abscissa) of the 105 sample points of Tables S1 and S2. d‐compounds inverted to l‐compounds (R 2=0.2944, ρ<3.85×10−9;102 compounds with negative rotation angles).

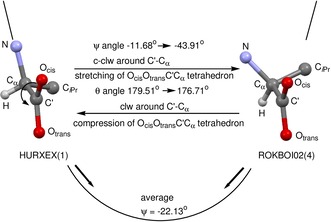

Movement along the best‐fit line in Figure 2 describes readily occurring conformational changes as exemplified for the “reaction” HURXEX(1) → ROKBOI02(4). The descent from HURXEX(1) to ROKBOI02(4) along the best‐fit line implies a rotation around the C′−Cα axis in a specific direction and an increasing distortion of the flat tetrahedron. Rotation around the C′−Cα axis of HURXEX(1) from −11.68° to −43.91° of ROKBOI02(4) is a counter‐clockwise (c‐clw) movement of 32.23°. It is associated with a stretching of the flat tetrahedron, indicated by an increase of the pyramidalization angle from 179.51° to 176.71° (Figure 3). The other way round, the ascent from HURXEX(1) to ROKBOI02(4) is a clockwise rotation around C′−Cα combined with a compression of the flat tetrahedron.

Figure 3.

Conformational “reactions” HURXEX(1)→ROKBOI02(4) and ROKBOI02(4)→HURXEX(1).

In Figure 3 the reaction HURXEX(1) → ROKBOI02(4) is embedded in an energy profile with respect to rotation around the C′−Cα bond in valine. The accumulation of sample points is interpreted as the energy minimum.4, 5 Following the arrows towards the energy minimum, conformations of type HURXEX(1) rotate preferentially counter‐clockwise stretching the flat tetrahedron, whereas those of type ROKBOI02(4) rotate clockwise flattening the tetrahedron.

Table 3 summarizes rotation and pyramidalization angles as well as distances and bond angles of valine‐containing tripeptides (Figure 1 D). There is not much difference between valine at the amino end, in the middle or at the carboxy end and the results are well in line with the valine structures in Tables S1 and S2.

Table 3.

Valine in tripeptides.

| Entry | CSD symbol[a] | Tripeptide | Chirality chain | Distances [Å] | Attraction CαN/C′O angles [°] | Comments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Config. Cα |

Ocis‐C′‐Cα‐N ψ [°] |

Otrans(Namide)‐C′α‐Ocis

θ [°] |

Ocis−N | Ocis−C(iPr) | N‐Cα‐C′(O) | (iPr)C‐Cα‐C′(O) | ||||

| 1 | DVLTLV10[b] | Val‐Trp‐Val | DLL | 15.58 | 177.88 | 2.87 | 3.07 | 107.25 | 110.44 | amino end (D) |

| 2 | AQOWAE | Val‐Gly‐Gly | L | −0.79 | −179.35 | 2.70 | 3.52 | 109.44 | 111.35 | carboxy end, HCl |

| 3 | BEVYIL | Val‐Val‐Val | LLL | −31.74 | −176.74 | 2.75 | 3.26 | 109.74 | 109.47 | carboxy end, CF3COOH |

| 4 | XEPZAU(1) | Val‐Ile‐Ala | LLL | −42.92 | −177.06 | 2.74 | 3.15 | 107.71 | 112.67 | |

| 5 | BEVYIL | Val‐Val‐Val | LLL | −43.80 | −176.67 | 2.76 | 3.06 | 107.23 | 108.82 | amino end, CF3COOH |

| 6 | XEPZAU(2) | Val‐Ile‐Ala | LLL | −44.68 | −174.99 | 2.74 | 3.08 | 107.34 | 110.63 | |

| 7 | XEPZAU(3) | Val‐Ile‐Ala | LLL | −46.51 | −178.50 | 2.74 | 3.05 | 105.97 | 110.19 | |

| 8 | XEPZAU(4) | Val‐Ile‐Ala | LLL | −47.69 | −177.44 | 2.76 | 3.05 | 106.91 | 110.16 | |

| 9 | BEVYIL | Val‐Val‐Val | LLL | −50.01 | −177.49 | 2.81 | 3.06 | 108.95 | 110.31 | carboxy end |

| 10 | CUWRUH | Gly‐Gly‐Val | L | −50.71 | −180.21 | 2.86 | 3.11 | 110.28 | 111.96 | |

| 11 | DVLTLV10 | Val‐Trp‐Val | DLL | −52.20 | −178.29 | 2.62 | 3.35 | 110.03 | 111.68 | carboxy end (L) |

| 12 | BEVYIL | Val‐Val‐Val | LLL | −54.03 | −178.68 | 2.82 | 3.03 | 106.78 | 109.25 | middle CF3COOH |

| 13 | BEVYIL | Val‐Val‐Val | LLL | −54.47 | −176.94 | 2.89 | 2.96 | 106.41 | 108.78 | amino end |

| 14 | COPBIS10 | Val‐Gly‐Gly | L | −58.32 | −178.58 | 2.86 | 3.00 | 107.05 | 110.78 | amino end |

| 15 | BEVYIL | Val‐Val‐Val | LLL | −58.51 | −179.75 | 2.84 | 3.01 | 106.02 | 110.55 | middle |

| Average | −43.46 | −177.91 | 2.78 | 3.12 | 107.81 | 110.47 | ||||

[a] Parenthesis ( ) indicate independent molecules in the unit cell. [b] For average calculation rotation angle and pyramidalization angle inverted.

All the rotation angles of valine in the tripeptides are negative except for entry 1 (Table 3), which contains d‐valine at the amino end. They span the typical range from −0.79° to −58.51°. The (M)‐torsional system induces (S)‐chirality in the flat tetrahedron with one exception, the value −179.8° of which is close to −180°. The distances Ocis−N are short and the bond angles N‐C′‐Cα are far below the tetrahedral angle due to the attraction CαN/C′Ocis.

As the analysis of valine‐containing dipeptides comprises 78 examples, Table S3 is given in the Supporting Information. The results correspond to those obtained up to now. The range of rotation angles is from 6.45° to −71.60° except for MOBYEH, which contains 8 independent molecules, four of which have the expected small negative rotation angles. However, four MOBYEH molecules have the unfavorable syn‐conformation with respect to the C′−Cα bond, which entails large rotation angles. The selectivity of distortion of the flat tetrahedron is better than 80 %. The distances Ocis−N and Ocis−C(iPr) as well as the angles N−C′−Cα and (iPr)C−Cα−C′(O), confirming the attraction CαN/C′Ocis, are comparable to Tables S1 and S2.

Pyramidalization of the unit CαC′(O)O in Val is caused by the Cα−N/C′−Onear attraction. There are other weak interactions, resulting in pyramidalizations, for example, n→π* interactions. In proteins, the approach of an adjacent C=O group to the C′ position of a carboxamide below 3.22 Å is considered a weak non‐covalent n→π* attraction.6 In the dipeptides of Table S3, three such pyramidalizations by n→π* interactions are present (entries 5, 10, 28).

The small negative ψ angle and the induced (S)‐pyramidalization, controlled by the configuration at the Cα position and the attraction Cα−N/C′−Ocis, are inherent properties of the l‐Val molecule, which may be overruled in proteins by other effects. Thus, valine enters into α‐helix domains with small negative ψ angles and (S)‐pyramidalization. However, when valine is used as a building block in β‐sheet domains, dramatic changes in the ψ angles and a chirality change of the pyramidalization takes place.7, 8

As other amino acids show similar effects as valine, further studies are in progress.

Experimental Section

The Cambridge Structural Database ver. 5.399 (update May 2018) was used for a search of the compounds in Tables 1–3 and Tables S1–S3. The programs OLEX 2,10 Mercury CSD ver. 3.10.2,11 and ConQuest ver. 1.2212 were used for the structure analyses.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

H. Brunner, T. Tsuno, ChemistryOpen 2018, 7, 696.

Dedicated to Prof. Dr. Manfred Scheer, the successor of Prof. Dr. Henri Brunner on the Chair of Chemistry at the University of Regensburg

Contributor Information

Prof. Dr. Henri Brunner, Email: henri.brunner@chemie.uni-regensburg.de.

Prof. Dr. Takashi Tsuno, Email: tsuno.takashi@nihon-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1. Cahn R. S., Ingold C., Prelog V., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1966, 5, 385–415; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1966, 78, 413–447. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alvarez S., Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 8617–8636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Publication in preparation.

- 4. Bye E., Scheizer B., Dunitz J. D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 5893–5898. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brunner H., Balázs G., Tsuno T., Iwabe H., ACS Omega 2018, 3, 982–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Newberry R. W., Raines R. T., Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 1838–1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Esposito L., Vitagliano L., Zagari A., Mazzarella L., Protein Sci. 2000, 9, 2038–2042. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hollingsworth S. A., Karplus P. A., Biomol. Concepts 2010, 1, 271–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Groom C. R., Bruno I. J., Lightfoot M. P., Ward S. C., Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 2016, B72, 171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dolomanov O. V., Bourhis L. J., Gildea R. J., Howard J. A. K., Puschmann H. J., Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Macrae C. F., Bruno I. J., Chisholm J. A., Edgington P. R., McCabe P., Pidcock E., Rodriguez Monge L., Taylor R., van de Streek J., Wood P. A., J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 466–470. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bruno I. J., Cole J. C., Edgington P. R., Kessler M., Marcrae C. F., McCabe P., Pearson J., Taylor R., Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 2002, B58, 389–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary