Abstract

A 23-year-old woman was referred to the tertiary centre with acute kidney injury and severe metabolic alkalosis following an accidental ethylene glycol poisoning. The patient had been treated with continuous haemodiafiltration and regional citrate anticoagulation, and a tracheostomy was performed due to pneumonia. Besides severe metabolic alkalosis and hypernatremia, the laboratory tests revealed total protein of 108 g/L on admission to the tertiary centre. The haemodiafiltration with regional citrate anticoagulation continued with parallel correction of the alkalosis and normalisation of the total plasma protein. The tracheostomy was decannulated and the patient was discharged to the district hospital. The case demonstrates the usefulness of regional citrate anticoagulation even in severe metabolic alkalosis which was likely related to the method setting prior to admission and to an overcompensation of the initial severe metabolic acidosis. The unusual hyperproteinaemia might be interpreted with the aid of the Stewart-Fencl model of the acid-base regulation.

Keywords: Citrate accumulation, Continuous renal replacement therapy, Hyperproteinaemia, Metabolic alkalosis, Regional citrate anticoagulation, Stewart-Fencl acid base concept

Introduction

Metabolic alkalosis is one of the known side effects of regional citrate anticoagulation (RCA), and heparin anticoagulation is advocated if alkalosis is severe. Many units apply RCA as a default and when carefully adjusted to the patient's needs (here bleeding from tracheostomy, metabolic alkalosis, and hypernatremia), it may safely stabilise homeostasis even in critical metabolic alkalosis. The case also demonstrates unusual hyperproteinaemia, which might be interpreted using the Stewart-Fencl concept of acid-base regulation.

Case Report

A 23-year-old otherwise healthy woman was referred to a medical high-dependency unit in a regional hospital after 1 week of hypogastric pain and vomiting. The only previous medical history was a suicide attempt 7 years ago. On admission to the regional hospital, she presented with expressive aphasia, vertigo, and unsteady gait.

Laboratory findings were severe metabolic acidosis with hyperlactataemia (see Table 1). Brain computed tomography and lumbar puncture showed no pathology. She was treated with 680 mmol of i.v. bicarbonate, infusions, and antipyretics due to pyrexia. Toxicology screening showed traces of ethylene glycol and abundant glycolic acid in urine, which triggered immediate therapy with i.v. ethanol. After 16 h, she lost consciousness, developed convulsions, was intubated, and was admitted to the intensive care unit. Her status complicated with an aspiration pneumonia, sepsis, and renal failure. Toxicology confirmed ethylene glycol poisoning, likely dozens of hours or days prior to admission. The treatment included antibiotics for pneumonia and continuous haemodiafiltration.

Table 1.

Selected laboratory parameters on days 0, 16 (admission to tertiary hospital), 19, and 23 (discharge from tertiary hospital)

| Day 0 | Day 16 | Day 19 | Day 23 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 6.70 | 7.64 | 7.52 | 7.43 |

| Sodium, mmol/L | 158 | 158 | 143 | 136 |

| Potassium, mmol/L | 5.2 | 5.4 | 4.0 | 4.3 |

| Total calcium, mmol/L | 1.69 | 3.13 | 2.13 | 1.99 |

| Magnesium, mmol/L | 0.82 | 1.07 | 1.59 | 1.52 |

| Chloride, mmol/L | 114 | 86 | 101 | 100 |

| Phosphate, mmol/L | 2.72 | 0.92 | 1.15 | 1.86 |

| Lactate, mmol/L | 14 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.1 |

| Total plasma protein, g/L | 56 | 62 | 107.7 | 73.5 |

| Albumin, g/L | 33 | 28 | 40.2 | 46.8 |

| paCO2, kPa | 1.52 | 8.01 | 4.64 | 4.48 |

| Atot–, mEq/L | 10.73 | 10.38 | 12.10 | 13.75 |

| SID, mmol/L | 13.53 | 75.28 | 46.4 | 37.5 |

| XA–, mmol/L | 38.18 | 6.32 | 3.32 | 6.76 |

Atot-, weak acids; SID, strong ion difference; XA–, unmeasured anions including lactate.

Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) used bicarbonate-buffered solutions (CRRT dosage 1.6 L/h) and citrate-calcium module (Ci-Ca). The estimated citrate level within the blood circuit was 4.0–4.7 mmol/L throughout the run of CRRT.

After improvement of consciousness, an extubation attempt was made on day 7, which failed on day 8 due to sputum retention with subsequent reintubation. A dilatation tracheostomy was made on day 12. Unfortunately, it required two revisions due to bleeding in the following days.

The patient was referred to the tertiary hospital on day 16 due to the development of an intractable metabolic alkalosis, two organ failures, and a bleeding from tracheostomy.

Initial bronchoscopy on admission to the tertiary centre eliminated atelectasis and secured an open bronchial tree and the microbiology specimens. These allowed ceasing the antibiotics after 5 days (day 21). Echocardiography showed mildly globally reduced ejection fraction of the left ventricle and a thrombus in the right internal jugular vein, likely related to the previous cannulation. Chest X-ray showed an infiltration of the right lower lobe consistent with previously diagnosed and treated aspiration pneumonia.

The laboratory test on admission to the tertiary centre confirmed metabolic alkalosis, hypernatraemia (see Table 1), and elevation of the renal parameters - urea of 37 mmol/L and serum creatinine of 422 μmol/L. Total to ionised calcium ratio was 2.42 (2.93/1.21), indicating citrate accumulation [1]. There was markedly high total plasma protein of 107.7 g/L, which led to an extension for the electrophoresis as part of the differential diagnosis of the suspected hyperviscosity syndrome. This investigation was subsequently repeated (for both, see Table 2).

Table 2.

Electrophoresis of plasma protein on days 19 and 22

| Day 19 | Day 22 | Reference range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total protein, g/L | 107.7 | 73.5 | 65–85 |

| Albumin, % | 40.2 | 46.8 | 55.8–66.1 |

| Alpha 1 globulins, % | 10.9 | 7.2 | 2.9–4.9 |

| Alpha 2 globulins, % | 10.2 | 10.7 | 7.1–11.8 |

| Beta 1 globulins, % | 6 | 5.2 | 4.7–7.2 |

| Beta 2 globulins, % | 8.4 | 5.3 | 3.2–6.5 |

| Gamma globulins, % | 24.3 | 24.8 | 11.1–18.8 |

| Albumin-globulin ratio | 0.67 | 0.88 |

Based on pathologic results of the electrophoresis, an immunoassay on the free light chains was performed on day 21. The findings of free kappa of 170 mg/L (reference range 3.3–19.4), free lambda of 106 mg/L (reference range 5.71–26.3), and kappa/lambda ratio of 1.61 (range 0.26–1.55) exclude a suspected myeloma.

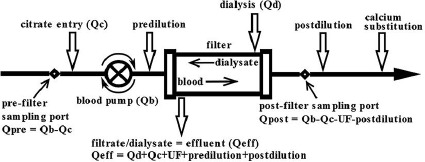

The patient was treated with CRRT and RCA (Fig. 1) with 4$ trisodium citrate, 10$ calcium chloride replacement, and calcium-free lactate-buffered solution (Lactocitrate®, GML, Czech Republic). With flow of dialysate at 1.5 L/h, the plasmatic natrium was lowered by 10 mmol/L in the first 24 h. Then, incrementing the dialysate flow to 2.2 L/h, the normal acid-base parameters were reached on day 20. In the meantime, the patient restored consciousness and after weaning of the respiratory support was decannulated on day 22. On day 23, CRRT was ceased after restoration of diuresis and the patient was transferred back to the regional hospital high-dependency unit.

Fig. 1.

Scheme of continuous hemodiafiltration with regional citrate anticoagulation.

She was improving slowly and was discharged home from the regional hospital on day 48 with no need for any kind of renal replacement therapy. At the time of submission of this case report, the patient is at home in a good performance status, with healed tracheostomy and normal renal functions, taking care about her child.

Protocol of Regional Citrate Anticoagulation (Fig. 1)

The protocol of CRRT at the intensive care unit in the tertiary hospital encompasses the AquariusTM (Nikkiso Medical, UK) machine fitted with a large area high-flux polysulfone filter (Bellco, Mirandola, Italy, 1.9 m2). Regional blood decalcification is provided by the 4$ trisodium citrate, which is administered prefilter. Calcium is replaced in the form of 10$ calcium chlorate infused to the venous limb of the circuit just before returning blood into the patient's circulation. The default initial citrate flow is 200 mL/h with correction according to the post-filter level of ionised calcium targeting 0.25–0.35 mmol/L. 10$ calcium chloride continuous infusion starts at 10 mL/h and is then titrated to maintain arterial ionised calcium between 0.85 and 1.2 mmol/L. The default dialysis/replacement fluid is the calcium-free lactate-buffered solution LactocitrateⓇ (GML, Czech Republic) [2].

The current protocol secures normal homeostasis and normal lactate levels [3] balancing input of citrate related to the blood flow with the flow of acidic dialysis/substitution fluid. The applied model of blood flow around 90–110 mL/min enables “flow-limited dialysis” on a large-area filter [2, 3, 4, 5]. The calcium-citrate complex is partly dialysed (35–40$) [4] and partly metabolised in the liver and other tissues producing bicarbonate. Both the administered citrate and lactate are valuable energetic sources [3]. Both ionised calcium levels from the circuit and from the patient are measured every 3–6 h. The whole procedure is performed according to the algorithm by an intensive care nurse.

Discussion

After exposure to the prolonged metabolic acidosis due to the ethylene glycol poisoning, the patient developed a severe metabolic alkalosis while treated with RCA. Of note, the initial hyperlactataemia was most likely pseudolactataemia consistent with a picture of ethylene glycol poisoning [6]. Moreover, there were no other obvious explanations for high lactate levels.

The estimated circuit citrate levels do not explain the alkalosis; however, they were at the upper normal level (4.0–4.7 mmol/L) [7, 8]. The increased load of citrate might not be compensated by an administered CRRT dosage of 1.6 L/h representing 23 mL/kg•h. The high sodium level developed also in relation to the administration of high volume of trisodium citrate. Depending on the area of applied filter, this amount may not provide adequate removal of the citrate-calcium complexes in the effluent nor balance the systemic load of substrates, which are converted to bicarbonate in the intermediate metabolism [3, 4]. The homeostatic stability was resolved with balanced dosage of RCA as depicted after the admission to the tertiary centre.

High plasma protein with potential hyperviscosity syndrome in a patient with no previous protein substitution is a form of plasma or albumin required to exclude monoclonal gammopathy and multiple myeloma. The electrophoresis and the levels of light chain proteins (Table 2) showed pathologic numbers; however, the ratio remained close to normal (or in a wider range of normal [9]), virtually excluding monoclonal gammopathies.

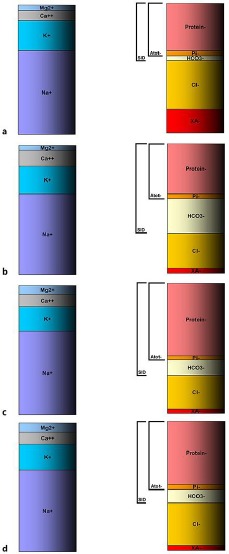

Excluding an impact of dehydration, the authors hypothesise about the gross hyperproteinaemia as an accompanying phenomenon in a severe homeostatic disorder in a patient with preserved liver function and relative haemodynamic stability. This could be interpreted applying the Stewart-Fencl concept and the rule of electroneutrality. The negatively charged plasmatic proteins increased weak acids and the strong ion difference (SID) compensating the removal of abundant bicarbonate by CRRT.

The parameters of acid-base status were calculated using the following formulas [10]:

SID = HCO3– + Atot–

XA– = Na+ + K+ + Ca2+ + Mg2+ - Cl– - SID

Atot− = Alb × (0.123 × pH − 0.631) + Pi × (0.309 × pH − 0.469)

The results are demonstrated in Table 1 and in a non-proportional scheme (Fig. 2). Our hypothesis might be further supported by the methodology calculating Atot– with a total protein [11] and not only albumin. This methodology, however, is questionable as it omits the positively charged plasmatic proteins and reflects the negatively charged ones, which are the majority.

Fig. 2.

Schematic (non-proportional) development of acid-base status using the Stewart-Fencl approach. a Day 0: admission, severe metabolic acidosis due to ethylene glycol and its metabolites. Low bicarbonate is partly caused by renal failure. b Day 16: admission to tertiary centre, severe metabolic alkalosis, high SID made by markedly elevated bicarbonate level. c Day 19: normal pH achieved by dialysis removal of abundant bicarbonate and by rising hyperproteinemia. d Day 22: restoration of normal conditions. Atot–, weak acids; Pi–, inorganic phosphate; SID, strong ion difference; XA–, unmeasured anions, i.e., lactate; Cl–, measured chloride.

The literature mentioning treatment of metabolic alkalosis using CRRT, and particularly together with RCA, remains scarce [12, 13]. Nevertheless, a number of units use RCA as a default on all continuous or extended dialysis circuits. The reasons are described in a meta-analysis [14] showing the advantages of RCA modalities over heparin anticoagulation and the KDIGO Guidelines [15] promoting RCA as an ideal intensive care modality which should be applied even in a patient without bleeding risk.

Statement of Ethics

The patient's next of kin signed an informed consent form to publish the case at the time of the patient's discharge from the tertiary centre.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no financial or other conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Link A, Klingele M, Speer T, Rbah R, Pöss J, Lerner-Gräber A, et al. Total-to-ionized calcium ratio predicts mortality in continuous renal replacement therapy with citrate anticoagulation in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2012 May;16((3)):R97. doi: 10.1186/cc11363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balik M, Zakharchenko M, Leden P, Otahal M, Rulisek J, Brodska H, et al. The effects of a novel calcium-free lactate buffered dialysis and substitution fluid for regional citrate anticoagulation—prospective feasibility study. Blood Purif. 2014;38((3–4)):263–72. doi: 10.1159/000369956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balik M, Zakharchenko M, Leden P, Otahal M, Hruby J, Polak F, et al. Bioenergetic gain of citrate anticoagulated continuous hemodiafiltration—a comparison between 2 citrate modalities and unfractionated heparin. J Crit Care. 2013 Feb;28((1)):87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balik M, Zakharchenko M, Otahal M, Hruby J, Polak F, Rusinova K, et al. Quantification of systemic delivery of substrates for intermediate metabolism during citrate anticoagulation of continuous renal replacement therapy. Blood Purif. 2012;33((1–3)):80–7. doi: 10.1159/000334641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgera S, Schneider M, Slowinski T, Vargas-Hein O, Zuckermann-Becker H, Peters H, et al. A safe citrate anticoagulation protocol with variable treatment efficacy and excellent control of the acid-base status. Crit Care Med. 2009 Jun;37((6)):2018–24. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a00a92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fijen JW, Kemperman H, Ververs FF, Meulenbelt J. False hyperlactatemia in ethylene glycol poisoning. Intensive Care Med. 2006 Apr;32((4)):626–7. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0076-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Ostermann M. Bench-to-bedside review: citrate for continuous renal replacement therapy, from science to practice. Crit Care. 2012 Dec;16((6)):249. doi: 10.1186/cc11645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider AG, Journois D, Rimmelé T. Complications of regional citrate anticoagulation: accumulation or overload? Crit Care. 2017 Nov;21((1)):281. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1880-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katzmann JA, Clark RJ, Abraham RS, Bryant S, Lymp JF, Bradwell AR, et al. Serum reference intervals and diagnostic ranges for free kappa and free lambda immunoglobulin light chains: relative sensitivity for detection of monoclonal light chains. Clin Chem. 2002 Sep;48((9)):1437–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fencl V, Jabor A, Kazda A, Figge J. Diagnosis of metabolic acid-base disturbances in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000 Dec;162((6)):2246–51. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.9904099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kellum JA, Elbers PW, editors. London: Lulu Enterprises, UK Ltd.; (2009). Stewart's Textbook of Acid-Base (p. 236) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yessayan L, Yee J, Frinak S, Kwon D, Szamosfalvi B. Treatment of Severe Metabolic Alkalosis with Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy: Bicarbonate Kinetic Equations of Clinical Value. ASAIO J. 2015 Jul-Aug;61((4)):e20–5. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu SC, Wang MC, Liu HL, Tsai MC, Huang JJ. Extreme metabolic alkalosis treated with normal bicarbonate hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001 Apr;37((4)):E31. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(01)90017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu MY, Hsu YH, Bai CH, Lin YF, Wu CH, Tam KW. Regional citrate versus heparin anticoagulation for continuous renal replacement therapy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012 Jun;59((6)):810–8. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Global KDI Group OKAKIW Kdigo clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney inter. 2012;2:1–138. [Google Scholar]