Abstract

Focal neuroinflammation is considered one of the hypotheses for the cause of temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) with amygdala enlargement (AE). Here, we report a case involving an adult female patient with TLE-AE characterized by late-onset seizures and cognitive impairment. Anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) antibodies were detected in her cerebrospinal fluid. However, administration of appropriate anti-seizure drugs (ASD), without immunotherapy, improved TLE-AE associated with NMDAR antibodies. In the present case, two clinically significant observations were made: 1) anti-NMDAR antibody-mediated autoimmune processes may be associated with TLE-AE, and 2) appropriate administration of ASD alone can improve clinical symptoms in mild cases of autoimmune epilepsy.

Keywords: Amygdala enlargement, Anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antibody, Autoimmune encephalitis, Temporal lobe epilepsy

Highlights

-

•

Anti-NMDAR antibody-mediated autoimmune processes may be associated with temporal lobe epilepsy with amygdala enlargement

-

•

Administration of an appropriate anti-seizure drug, without immunotherapy, improved clinical symptoms in this patient

-

•

This patient presented with a milder form or “forme fruste” of anti-NMDAR encephalitis

1. Introduction

In recent years, an increasing number of reports have indicated an association between amygdala enlargement (AE) and temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) [1]. Focal neuroinflammation is considered one of the hypotheses for the cause of TLE-AE. However, the etiology is not fully understood, and there is no consensus regarding its treatment. Here, we describe a patient with TLE-AE associated with Anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) antibody. Administration of appropriate anti-seizure drugs (ASD), without immunotherapy, improved her clinical symptoms.

2. Case

A right-handed female office worker in her 50's was admitted to an outside hospital for the evaluation of cognitive dysfunctions, emotional disturbances, and suspected epilepsy. She had a history of breast cancer (stage 0) in her 40's, but no other significant medical history. She had experienced impaired attention, memory deficits, and emotional instability for 6 years. She received various pharmacotherapies under the diagnosis of depression and early-onset dementia, but her symptoms did not improve. By the second year, her colleagues witnessed her staring, suggesting the possibility of epileptic seizures. Therefore, she began receiving valproic acid, 400 mg daily. However, brief episodes of impaired consciousness continued, and her cognitive dysfunction gradually worsened. Consequently, she was forced to discontinue working.

On mental status examination, she demonstrated bradykinesia and bradyphrenia. Her family reported witnessing focal seizures, with loss of consciousness, on a weekly to monthly basis.

We recorded one habitual seizure during 24-hour inpatient video-electroencephalographic (EEG) monitoring. A focal impaired awareness seizure, with behavioral arrest, blank stare, and unresponsiveness, lasted approximately 50 s. Ictal EEG recordings showed rhythmic waveforms of varying amplitude and frequency in the temporal region on the left side. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) indicated left AE with hyperintense T2/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery signal (Fig. 1) upon visual inspection by a certificated radiologist and a certificated epileptologist. Interictal brain single-photon emission computed tomography using N-isopropyl-[123I]-p-iodoamphetamine showed hypoperfusion in the left hemisphere. The diagnosis of TLE-AE was established, and she was started on carbamazepine (CBZ), 200 mg daily. After starting CBZ, focal impaired awareness seizures were controlled; her mood symptoms and cognitive impairment also abated. She was discharged home on CBZ, following which, her treatment was changed to zonisamide (ZNS) monotherapy because of a rash.

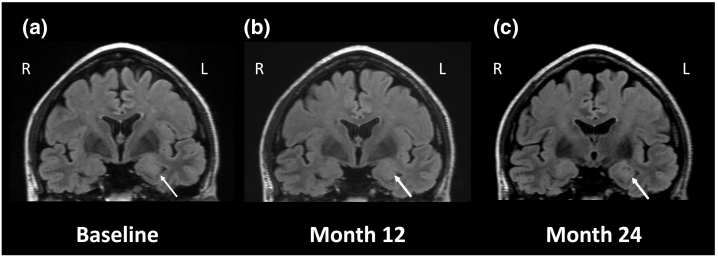

Fig. 1.

Changes in amygdala volume in coronal fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MRI images.

(a) Enlargement of and high signal intensity in the left amygdala (arrow) are detected at initial hospitalization (Baseline). (b) MRI conducted after 12 months of cessation of seizures shows reduction of left amygdala enlargement. (C) MRI obtained after 24 months of cessation of seizures shows remission of amygdala enlargement and recovery of hyperintensity.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) antibody test results arrived during outpatient follow-up, and revealed the presence of anti-NMDAR antibodies, detected by both cell-based assay and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. We performed a search for underlying tumors, but none were found.

Immunotherapy was proposed because we suspected that anti-NMDAR antibody-mediated autoimmune processes might cause TLE-AE, but the patient and her family were reluctant to implement it because they believed she had already recovered to her premorbid state. We respected their opinions and decided to treat her without administering immunotherapy. During a 3-year follow-up, she maintained seizure freedom on ZNS 200 mg daily, and neuropsychological examination revealed that her verbal intelligence quotient and memory functions were particularly improved (Fig. 2). Moreover, reduction in the volume of the enlarged amygdala was observed on MRI. The most recent MRI showed that the difference in volume between the left and right amygdalae had disappeared. Subsequently, she regained her job and continues to work. She provided written informed consent for the publication of this case report.

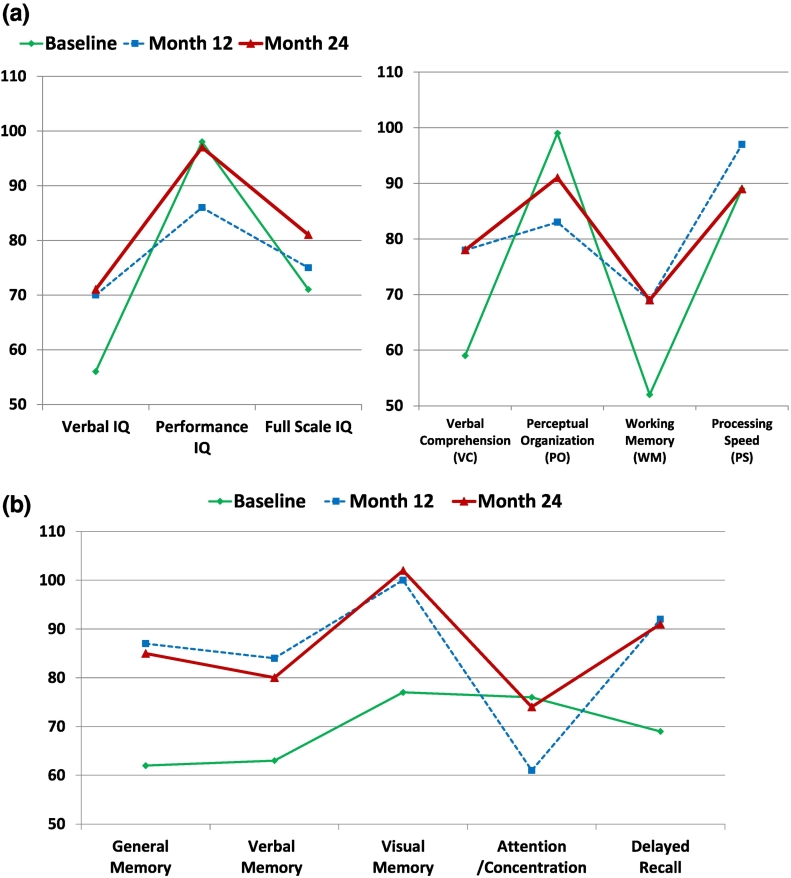

Fig. 2.

Chronological change of neuropsychological examinations.

(a) WAIS-III: Changes in IQ score reveal remarkable improvement in verbal IQ and increase in full IQ score after the cessation of seizures (left). Verbal comprehension and working memory are particularly improved after the cessation of seizures in subcategories of WAIS-III (right).

(b) WMS-R scores: Attention/concentration scores decreased transiently, but in other categories of memory function, significant improvement was recognized after the cessation of seizures.

Neuropsychological examinations reveal the changes in the patient's verbal IQ and memory as the left temporal function was particularly improved after the cessation of seizures due to appropriate ASD.

WAIS-III: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Third Edition, WMS-R: Wechsler Memory Scale – Revised, IQ: Intelligence Quotient.

3. Discussion

In the present case, we made two clinically significant observations: 1) anti-NMDAR antibody-mediated autoimmune processes may be associated with TLE-AE, 2) appropriate administration of ASD alone can improve clinical symptoms in mild cases with autoimmune TLE-AE.

In our patient, the characteristics of the seizure-related features were: a later onset of seizure; greater frequency of focal impaired awareness, rather than convulsive, seizures; and ipsilateral interictal discharges over the enlarged amygdala. Her MRI findings are consistent with those in previous reports of TLE-AE [1]. Besides the common features of TLE-AE, other clinical features, such as memory and emotional disturbances, and presence of anti-NMDAR antibodies in CSF, also meet the proposed diagnostic criteria for anti-NMDAR encephalitis [2]. However, the present case was different from the typical anti-NMDAR encephalitis in that the progress was slow and there were no other symptoms, such as abnormal movements, decreased level of consciousness, or autonomic dysfunction. Therefore, we believe that our patient presented with a milder form or “forme fruste” of anti-NMDAR encephalitis. To date, a few reports have indicated that voltage-gated potassium channel (VGKC)-complex or glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibodies are among the pathophysiological factors underlying autoimmune TLE-AE [1], [3]. No previous reports have demonstrated the presence of anti-NMDAR antibodies in TLE-AE; to the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report indicating that anti-NMDAR antibody-mediated processes may be associated with TLE-AE.

Recently, Malter et al. reported a large group suspected of autoimmune TLE-AE based on clinical symptoms, and EEG and MRI findings, but test results for serum antibodies against cell membrane antigens, such as VGKC, GAD, NMDAR, and paraneoplastic antigens, were negative [4]. Since neuronal antibodies in the CSF were not measured in their cohort, the detection of anti-NMDAR antibody-associated TLE-AE may have been overlooked in some of their cases. Both CSF and serum tests for neuronal antibodies are mandatory for suspected cases of autoimmune encephalitis to prevent false-positive or false-negative diagnosis.

Second, appropriate administration of ASD alone can improve clinical symptoms in patients with milder form of autoimmune TLE-AE. It is known that appropriate administration of ASD results in good seizure control in most cases of TLE-AE. However, immunological tests have not been performed in many such cases, and the existence of antibodies may have been overlooked.

It is generally believed that immediate immunotherapy should be considered to prevent severe consequences when autoimmune etiology is suspected. However, in our patient, administration of ASD, without immunotherapy, terminated her TLE-AE seizures. As a result, her cognitive functions improved, and she was able to achieve social participation.

Similar to our case, some studies have reported cases involving patients with autoimmune epilepsy who respond adequately to treatment with ASD alone [5], [6], [7]. The largest observational study of 50 patients revealed that 10% of the patients with autoimmune epilepsy had become seizure-free with ASD treatment alone, and all of them had received ASD with sodium channel blocking properties, such as CBZ, phenytoin, lacosamide, and oxcarbazepine [7]. In a systematic review, Cabezudo-García et al. found that many of these patients were treated with ASD having sodium channel blocking properties [8]. The reason why only such ASD achieved seizure control in autoimmune epilepsy is unknown, but it is hypothesized that sodium channel blockers improve autoimmune encephalitis indirectly through their strong anti-seizure action for focal seizures or directly affect immune systems [5], [7].

Remission of AE was observed in our patient on MRI, which is consistent with a predictor for a favorable clinical outcome described in a previous study [4]. Therefore, it is important to observe the change in the volume of the enlarged amygdala by MRI during regular follow-ups. Voh Rhein et al. suggested that physicians should start treatment with ASD in mild cases of autoimmune encephalitis, evaluate its effectiveness, and initiate immunotherapy if there is an exacerbation of seizures, a deterioration of cognition or mood, or progress of the disease is indicated by MRI findings during follow-ups across 3 months [9]. By using these treatment strategies, it is possible to avoid unnecessary consumption of medical resources and the unacceptable side effects of immunotherapy. Moreover, these strategies may help avert the side effects from immunotherapy and extend to patients with contradictions to immunotherapy.

In conclusion, anti-NMDAR antibody-mediated autoimmune processes may be associated with TLE-AE, and appropriate administration of ASD alone can improve clinical symptoms in patients with a milder form of autoimmune TLE-AE. Further reports should be accumulated to determine whether anti-NMDAR-associated autoimmune pathology is present more frequently in TLE-AE, and whether the prognosis of a patient group treated with only ASD differs from that of a group receiving combination treatment with ASD and immunotherapy, in mild and subacute/chronic cases.

Disclosure

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Beh S.M.J., Cook M.J., D'Souza W.J. Isolated amygdala enlargement in temporal lobe epilepsy: a systematic review. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;60:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graus F., Titulaer M.J., Balu R., Benseler S., Bien C.G., Cellucci T. A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:391–404. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00401-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner J., Witt J.A., Helmstaedter C., Malter M.P., Weber B., Elger C.E. Automated volumetry of the mesiotemporal structures in antibody-associated limbic encephalitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:735–742. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-307875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malter M.P., Widman G., Galldiks N., Stoecker W., Helmstaedter C., Elger C.E. Suspected new-onset autoimmune temporal lobe epilepsy with amygdala enlargement. Epilepsia. 2016;57:1485–1494. doi: 10.1111/epi.13471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gast H., Schindler K., Z'Graggen W.J., Hess C.W. Improvement of non-paraneoplastic voltage-gated potassium channel antibody-associated limbic encephalitis without immunosuppressive therapy. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;17:555–557. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Podewils F., Suesse M., Geithner J., Gaida B., Wang Z.I., Lange J. Prevalence and outcome of late-onset seizures due to autoimmune etiology: a prospective observational population-based cohort study. Epilepsia. 2017;58:1542–1550. doi: 10.1111/epi.13834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feyissa A.M., López Chiriboga A.S., Britton J.W. Antiepileptic drug therapy in patients with autoimmune epilepsy. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017;4 doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabezudo-García P., Mena-Vázquez N., Villagrán-García M., Serrano-Castro P.J. Efficacy of antiepileptic drugs in autoimmune epilepsy: a systematic review. Seizure. 2018;59:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Rhein B., Wagner J., Widman G., Malter M.P., Elger C.E., Helmstaedter C. Suspected antibody negative autoimmune limbic encephalitis: outcome of immunotherapy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;135:134–141. doi: 10.1111/ane.12575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]