Abstract

Background

Providing culturally competent and person-centered care is at the forefront of changing practices in behavioral health. Significant health disparities remain between people of color and whites in terms of care received in the mental health system. Peer services, or support provided by others who have experience in the behavioral health system, is a promising new avenue for helping those with behavioral health concerns move forward in their lives.

Purpose

We describe a model of peer-based culturally competent person-centered care and treatment planning, informed by longstanding research on recovery from serious mental illness used in a randomized clinical trial conducted at two community mental health centers.

Methods

Participants all were Latino or African American with a current or past diagnosis within the psychotic disorders spectrum as this population is often underserved with limited access to culturally responsive, person-centered services. Study interventions were carried out in both an English-speaking and a Spanish-speaking outpatient program at each study center. Interventions included connecting individuals to their communities of choice and providing assistance in preparing for treatment planning meetings, all delivered by peer-service providers. Three points of evaluation, at baseline, 6 and 18 months, explored the impact of the interventions on areas such as community engagement, satisfaction with treatment, symptom distress, ethnic identity, personal empowerment, and quality of life.

Conclusions

Lessons learned from implementation include making cultural modifications, the need for a longer engagement period with participants, and the tension between maintaining strict interventions while addressing the individual needs of participants in line with person-centered principles. The study is one of the first to rigorously test peer-supported interventions in implementing person-centered care within the context of public mental health systems.

Introduction

Health disparities research indicates that ethnic minorities in urban environments comprise one of the most disenfranchised populations in American medicine [1]. Psychiatric services are rarely tailored to their needs, preferences, and cultural contexts, resulting in many individuals refusing services and others receiving poor quality care [2]. The awareness of these disparities [1] has led to the development of culturally responsive services to address the needs of multicultural populations [3], including person-centered planning (PCP) [4], a promising approach to promoting cultural responsiveness in care.

In addition to addressing disparities in care, PCP is recognized as a practice key to transforming the current mental health system to a person-centered, recovery orientation [2,5,6]. Person-centered care reshapes the practices of traditional treatment planning, which is dominated largely by symptom management, to an individualized approach addressing quality of life (QOL) concerns [7] that is organized around a person’s unique strengths and preferences [8,9]. The PCP approach may help to decrease health care disparities in part by incorporating an individual’s cultural preferences [10–12] such as seeking help from informal or ‘natural’ supports in his or her community (e.g., family, clergy, etc.) rather than relying on formal systems of support inside the mental health system.

Evidence suggests that between one quarter and two thirds of people diagnosed with schizophrenia experience an amelioration of symptoms and live productive lives in the community over time [13–16]. Still, people with psychosis often are viewed within the mental health system as unable to assume responsibility for directing their own care. Although emerging psychosocial interventions (e.g., Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) [17]) have been applied with increasing success among people with psychosis over the last decade [18], much work remains in transforming services to be person centered.

One promising adaptation to this PCP process is use of a facilitative advocate [19]. An advocate, also termed a ‘coach’ or ‘recovery mentor’, assists people with serious mental illnesses to identify hopes and dreams, and to ensure that these are used as the basis for the person-centered care plan. The current study incorporates peer advocates, people with personal experience with mental illness, into the PCP process builds on the growing evidence around ‘peer-based’ services [20–24], which involve ‘one or more persons who have a history of mental illness . . . offering services and/or supports to other people with serious mental illness who are considered to be not as far along in their own recovery’ [25]. The growth of peer-based services has been exponential over the previous decade, with peer providers providing services including outreach work, case management, as staff in social clubs and respite programs, working as coaches in supported employment or education programs, and mentoring people coming out of hospitals [20,26–29].

Evidence suggests that peer-based services are at least as effective as services provided by those without a personal history of illness [20]. Peer staff may be better able to develop rapport with ‘difficult-to-engage’ patients [30], and the recipients of peer-based services demonstrate decreased use of alcohol and other drugs and fewer hospitalizations [20,31,32]. Furthermore, peer-delivered services involve ‘giving and receiving help based on values of respect and mutual agreement . . . not based on psychiatric models’, which can increase a patient’s sense of self-worth [33–35]. Peers also act as potential role models who have survived and thrived, and can instill visceral hope for someone with mental illness [36]. Peer support remains a promising practice in need of stronger scientific support.

We describe the rationale, design, and lessons learned during the implementation of a randomized clinical trial testing the effect of using peer facilitative advocates to promote culturally responsive person-centered care planning on QOL variables, community connections, and coping for people of color with psychotic disorders. Although we suspect that the interventions examined in this study would be beneficial to all recipients in public mental health care, we focused our initial efforts on those who have been at greatest risk of being disempowered. The study sought to examine two primary hypotheses as follows: (1) that peer facilitative advocates increase the cultural responsiveness and person-centered nature of care and (2) that person-centered care planning in combination with peer-based community inclusion (CI) interventions improves outcomes for African Americans and Latinos with psychosis. This study represents the first of its kind to operationalize PCP interventions and to test these practices in a real-world context. This article is intended to serve as reference source illustrating design modifications and concerns.

Methods

Study design

The study is a randomized clinical trial of peer-supported PCP and community integration for African Americans and Latinos who have experienced psychosis in the context of either a thought or mood disorder. The study protocol was approved by both the Yale University Human Subjects Investigation Committee and the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services Institutional Review Board.

Participant eligibility

Participants in the experimental trial were eligible if they (a) self-identified as being of African and/or Latino origin; (b) were age 18 and older; (c) had experienced psychosis in the context of a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or affective disorder with psychotic features determined by provider diagnosis; and (d) were receiving outpatient psychiatric services at the time of recruitment. A broad definition of psychosis was used to represent the many manifestations of psychotic phenomena, arguably gaining external validity at the expense of internal validity [37]. Eligible individuals had a current or past diagnosis consistent with the DSM-IV-TR schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, or a current or past diagnosis of psychosis as a part of another Axis I disorder (e.g., bipolar affective disorder with psychotic features). Exclusion criteria included the presence of an organic brain syndrome or dementia.

Procedures

Recruitment, consent, and randomization

Recruitment of participants occurred at two large state-operated Community Mental Health Centers located in urban areas of Connecticut and serving people who are uninsured and living at or below the poverty level. Potentially eligible participants initially were identified via clinician, and subsequently were also recruited through fliers or by research team staff, including peer providers who hosted information tables at designated hours in lobby areas of the centers. Each center has individual outpatient programs for monolingual Spanish speaking Latinos.

Individuals who agreed to participate in the study completed an informed consent document. To ensure comprehension of the consent process, the research team developed a ‘Quiz for Understanding’ consisting of several multiple choice questions. In the development of the protocol, the team also redesigned recruitment forms to ensure that any legal conservatorship (a designated legal guardian) was included in the consent process. In some cases, individuals served by the public sector in Connecticut have been assigned a ‘conservator of person’ after being legally determined to be unable to make independent informed decisions. For those individuals, their conservator was contacted and the conservator provided consent, with the individuals providing assent.

Following completion of the baseline assessment, participants within each site were randomly assigned via a computer-generated random number protocol, which yielded a list of numbers then used by research assistants to assign participants to one of three study arms. Interviewers were blind to the arm at baseline data collection.

Trial arms

The control and two treatment arms in this trial are as follows:

-

1)

Control arm – standard care incorporating illness management (IMR). As standard care at each Community Mental Health Center typically varies widely, Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) training/materials were provided to clinicians at both sites in an effort to standardize routine outpatient services. IMR is an evidence-based approach to IMR skills training. ‘Illness Management and Recovery’ is a clinical ‘toolkit’, which has been developed as part of the National Evidence-Based Practices for Severe Mental Illness Project [38]. The program helps people set meaningful goals for themselves, acquire information and skills to develop more mastery over their psychiatric illness, and make progress toward their recovery through weekly sessions (individual or group) conducted by trained practitioners. Illness management was incorporated as an element of the control arm to provide a more rigorous comparison arm against which the experimental arms would be evaluated.

-

2)

Arm II – standard care plus facilitation of person-centered care (PCP). In addition to standard care with IMR, participants randomized to this arm are offered a peer mentor who is available to work in collaboration with the participant and his or her primary clinical provider to organize and conduct a series of planning meetings that bring together the individual with his or her network of professional and natural supports. Depending on individual preference, the peer mentor may accompany the participant to the planning meetings, or he/she may work directly with the participant ‘behind the scenes’ to support the individual in taking a more active role within the team planning sessions. The peer role is less formal than the typical service role, and the mentors are willing to meet with people at the times and locations of their preference (e.g., at a coffee shop). The peer mentors provide participants with information about the treatment planning process and how to communicate effectively with treatment providers, and conduct a strengths-based planning interview to identify aspirations, talents, and interests that may not have been incorporated into the plan previously. Mentors are available to provide premeeting preparation and coaching, and can attend the treatment planning meeting with the participant to help ensure that the participant’s preferences and priorities are not subverted, overtly or covertly, by others in attendance at the planning meeting, including professional helpers and significant others. The mentors also share their own experiences with treatment planning and information about their personal recovery process. The sharing of stories, experiences, hopes and dreams, and disappointments among people with similar life experiences is an important component of this arm. The initial series of PCP meetings between the participant and the mentor are convened within 1 month of the person’s enrollment in the study. During this period, the mentor gets to know the individual, educates him or her about the PCP process, and supports the discovery or rediscovery of aspirations, dreams, interests, and preferences. This information is then meant to inform subsequent formal PCP meetings that are carried out in collaboration with the study participant’s primary clinical provider and his or her natural support network (when desired by the person)

-

3)

Arm III – IMR/PCP plus CI. Community inclusion participants in this arm receive standard care and PCP and also ‘CI’ activities that consist of regular social and recreational group and/or individual outings that enable participants to join in the ongoing rhythms of community life. The arm is based on the premise that some individuals who have designed a more ‘person-centered plan’ with the support of a peer mentor (Arm 2) also will benefit from ongoing assistance to activate that plan and to carry out the community-based activities identified within it. Weekly CI groups consist of 6–10 study participants and take place over a 6-month period. The schedule of individual activities varies with participant need and interests. This intervention, again supported by peer staff trained in the role of community connectors, is an opportunity for study participants to pursue interests and develop valued roles. Staff in this intervention are titled community connectors to best describe their role in facilitating community outings designed to afford participants opportunities to learn, apply, and refine both social and daily living skills through participation in the activities of their choice surrounded, and supported by other people in recovery. It is based on an ‘in vivo’ approach to ‘supported community living’ [39,40] similar to other in vivo models in educational [41–45], vocational [46–48], residential [49,50], and social rehabilitation [50,51]. Within such models, skills and interests are developed in natural settings in which they are to be applied rather than in treatment locations. Activities in this arm are structured with progressive levels of participant autonomy. Independent of these weekly activities, participants are encouraged to identify other participants with whom they can share community explorations and excursions that involve common interests. Low-cost and seasonal activities are encouraged, as these are activities participants will likely continue on their own upon completion of the program. Community connection groups also focus on cultivating personal relationships as the key to increasing participants’ involvement in their treatment and in their communities. Thus, informal discussions and relationship building are encouraged to promote group interaction, unity, and mutual support among members.

Cultural modifications

Our attention to culture influenced several intervention modifications over the course of the study. First, we modified our strengths-based assessment tool used by our recovery mentors to ask explicitly about culture and culturally relevant experiences. We vetted these materials with our recovery staff and made additional changes based on feedback from participants. All materials were translated and back translated into Spanish for those participants who were monolingual Spanish speakers.

Beyond the importance of talking to Latino participants in their native language, bicultural Latino staff members were able to relate to participants by employing and being receptive to culturally appropriate colloquialisms and modes of expression. For example, after establishing trust through demonstrations of respect (e.g., initially using a formal address such as Usted), communication styles were often informal – characterized by teasing/joking, expressions of endearment (e.g., hija, mi negrita), slang, storytelling, and small talk (e.g., talking about soccer).

Focusing on personal as opposed to professional relationships (with both participants and referring clinical staff) was another important cultural modification, along with the selection and planning of culturally relevant community activities (food and fun). Location of community-based groups took place in comfortable environments, such as a Latino neighborhood church.

The study employed a wide range of people as peer workers, and we strove to increase the diversity of staff and to offer cultural competency training and experiences, and so on. However, during the course of the project, we found that there were important issues related to the ethnicity of the supervisory staff, many of whom are Caucasian. Participants, as well as community group leaders, noted this tension around a group including only African Americans as members. In the words of one participant, it was reminiscent of a ‘plantation’, watching the black group leaders with the white supervisory staff participating in the group of all African American participants. We synthesized this feedback from both participants and staff and made adjustments by having the supervisor step back from the group and bringing in additional African American staff. For another participant, being in a group restricted in membership by race/ethnicity was uncomfortable and felt discriminatory and against the mission of the civil rights movement.

Cultural competence and attention were transmitted as much or more through language, approach, and style as through specific rituals or activities. Participants also recounted stories regarding shared history in Puerto Rico, particularly growing up in rural areas, for example, talking about their recipes for appropriately fermenting sugarcane to make an alcoholic beverage for personal use or sale, or talking about famous Puerto Ricans. Conversations concerning the ‘conditions of the motherland’ appeared to help a migrant population to feel more connected to life in the mainland US. Participants also spontaneously talked about experiences of trauma related to their upbringing in Puerto Rico that may reflect their comfort with staff and other participants.

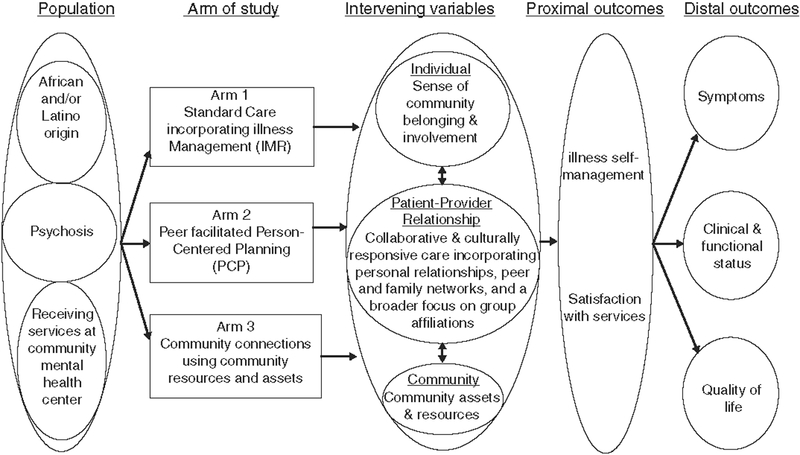

Selection of outcomes

The model depicted in Figure 1 stipulates the variables that we hypothesize to mediate the effects of illness management and PCP for low-income, urban adults of color with psychosis. Each intervention was carried out for a 6-month period following the baseline assessment.

Figure 1.

Illustration of arms in person-centered care for psychosis among low-income, urban adults of color interventions

We hypothesize that participants who receive person-centered care (Arms II and III) and CI support (Arm III) will have increased illness self-management and greater satisfaction with services than participants who received standard services/IMR only (Arm I). Primary outcome variable are self-management and satisfaction. Secondary outcomes are symptoms and QOL [52].

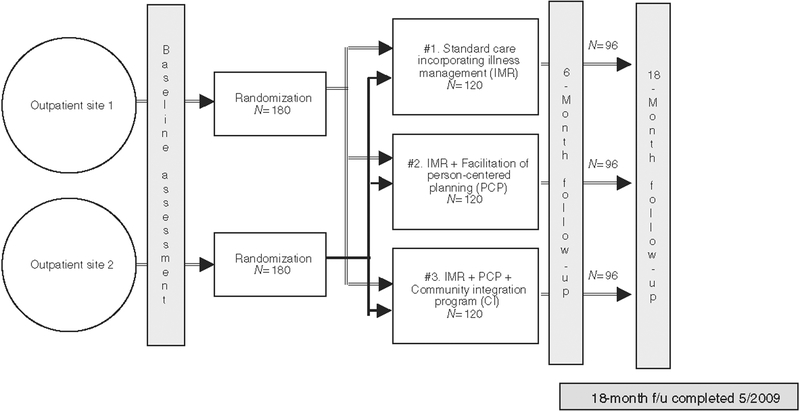

Assessment periods

Assessments were conducted at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months post intervention (typically an 18-month post baseline assessment). At each time period, trained research assistants administered a structured interview battery containing our measures of interest in the primary language of the participant (English or Spanish). Assessments took on average 90 min and were generally well received by participants. Figure 2 graphically represents the timeline for assessments and intervention periods.

Figure 2.

Design and timeline for the study

Table 1 contains measures associated with various levels of analyses and mechanisms of hypothesized change.

Table 1.

Measures used to assess fidelity, intervening variables, proximal outcomes, and distal outcomes associated with person-centered planning intervention

| Mechanism of change | Level of analysis | Construct | Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fidelity | N/A | Fidelity to illness management and recovery | Ongoing supervision and consultation |

| Fidelity to person-centered planning | Treatment Planning Questionnaire [44] | ||

| Intervening variables | Individual | Sense of community | Sense of Community Index [45,46] |

| Personality | NEO-Five-Factor Inventory [47] | ||

| Hopes and fears | Possible Selves [49,50] | ||

| Ethnic identity | Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure [51] | ||

| Scale of Ethnic Experiences [81] | |||

| Coping | Africultural Coping System Inventory [53] | ||

| Brief COPE [54] | |||

| Patient-provider relationship | Working alliance | Working Alliance Inventory - Short Form Revised [55] | |

| Autonomy and support in therapeutic relationship | Health Care Climate Questionnaire [56] | ||

| Recovery-oriented practices | Recovery Self-Assessment Revised [57] | ||

| Community | Social capital | Full Harmonized Social Capital Inventory [58] | |

| Proximal outcomes | Individual | Empowerment | Empowerment Scale [59] |

| Hope | Hope Scale [61] | ||

| Self-esteem | Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale [64] | ||

| Social support | Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL) [63] | ||

| Satisfaction with services | MHSIP Consumer Satisfaction Survey [65] | ||

| Distal outcomes | Individual | Quality of life | Quality of Life Interview [66] |

| Symptoms | Paranoid Ideation and Psychoticism | ||

| Subscales of the SCL-90 [67] | |||

| Symptom Distress Scale (adapted from Nguyen, | |||

| et al., 1993 for the MHSIP Mental | |||

| Health Report Card) | |||

| Medical health | Addiction Severity Index - Limited Form [68] | ||

| Alcohol and drug use | Addiction Severity Index - Limited Form [68] | ||

| Functioning | Global Assessment of Functioning - Modified Version [70] |

Fidelity

Fidelity to PCP was assessed at each time point using the Treatment Planning Questionnaire, a 49-item measure developed to assess the degree to which treatment planning meetings and plans themselves reflected principles of person-centered care [53].

Intervening variables

Three levels of intervening variables were examined in this study – the individual, the patient–provider relationship, and the community. At the level of the individual, data were collected on individual sense of community, personality dimensions, hopes and fears for the future, ethnic identity and experiences, and coping. Four facets of one’s sense of community were measured by the 12-item Sense of Community Index [54,55] that assesses membership, influence, reinforcement of needs, and shared emotional connection. The NEO-Five-Factor Inventory [56] was used to assess dimensions of personality, including neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness. The Possible Selves measure was used to assess hopes and fears for the future, likelihood of attaining each of the specified selves, and a rating of a sense of control in attaining the selves [57–59]. Ethnic identity was assessed via the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure [60], which is a 14-item measure designed to measure two dimensions of ethnic identity: ethnic identity search and ethnic identity achievement. In addition, we used the Scale of Ethnic Experiences [61], a 32-item self-report questionnaire that can be used across ethnic groups to measure various dimensions of ethnic identity. The Scale of Ethnic Experience (SEE) yields a total ethnic identity score and three subscale scores as follows: Perceived Discrimination, Social Affiliation, and Mainstream Comfort. Two coping inventories were used – the Africultural Coping System Inventory (ACSI) [62] and the Brief COPE[63]. The ACSI is a self-report, 30-item, scale designed to measure the coping behaviors employed by African Americans during stressful encounters with the environment. The Brief COPE is a 28-item measure assessing 14 conceptually different coping reactions.

Several measures were used to assess aspects of the patient–provider relationship. The Working Alliance Inventory – Short Form Revised (WAISFR) [64] is an abbreviated 12-item questionnaire that assesses three specific aspects of the therapeutic relationship between client and therapist including mutually agreed-upon goals, consensus on how to achieve these goals, and the strength of the bond that the participant perceives having with his/her clinician. The Health-Care Climate Questionnaire is a 17-item measure that assesses perceptions of the degree of autonomy and support offered within the clinical relationship [65]. The Recovery Self-Assessment Revised is a 32-item measure that assesses the degree to which practices at an organization are recovery oriented [66]. The Full Harmonized Social Capital Inventory was used to assess social capital. This instrument contains 45 items that capture dimensions of social participation, civic participation, social networks and social support, reciprocity and trust, and view of the local area [67].

Proximal outcomes

It is hypothesized that the changes in intervening variables will result in increased sense of empowerment and hope about the future, enhanced self-esteem, greater levels of social support, and greater satisfaction with services. Measures used included the Empowerment Scale [68], a 28-item, consumer-constructed scale that assesses five dimensions of empowerment as follows: self-esteem and self-efficacy, power/powerlessness, community activism and autonomy, optimism and control over the future, and righteous anger. The Hope Scale is a 12-item measure that assesses (a) agency (goal-directed determination) and (b) pathways (planning ways to meet goals) [69,70]. Social support was assessed using the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List [71,72]. This 40-item instrument measures perceived availability of four types of support – tangible support, appraisal support, self-esteem support, and belonging support. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, a 10-item measure, was used to assess positive and negative self-esteem [73]. Satisfaction with services was assessed using the MHSIP Consumer Satisfaction Survey [74].

Distal outcomes

Distal outcomes include QOL, symptoms and symptoms distress, medical health, alcohol, and drug use. QOL was assessed by the QOL interview [75], which assesses QOL across several domains including overall satisfaction with life, living situation, daily activities and functioning, family, social relations, finances, work and school, legal and safety issues, and health. Symptoms were assessed by the Paranoid Ideation and Psychoticism Subscales of the Symptom Checklist (SCL)-90 [76]. Symptom distress was measured by a 15-item instrument adapted from the SCL-90 anxiety dimension and SCL-10 [74] that was created for the MHSIP Mental Health Report Card. The Limited Form of the Addiction Severity Index was used to assess medical problems and alcohol and drug use [77,78] The Global Assessment of Functioning – Modified Version [79] is a scale (ranging from 1 to 100) that quantifies the rater’s judgment of the individual’s overall level of psychological, social, and occupational functioning.

Statistics

Statistical power

The selected sample size was calculated using the planned contrasts option of the power analysis module in STATISTICA (StatSoft, Inc, 2000). According to this calculation, a sample size of N = 190 is required for each contrast analysis that assumes a power of .80, a conventional alpha of .05, and a modest effect size (f = .25). Based on our previous experience with this population, we estimated an attrition rate of 16% per arm, which would provide an adequate number of participants (i.e., 202) for the main contrast between the IMR þ PCP and IMR þ PCP þ CI groups.

Planned statistical analyses

We will employ data reduction strategies in order to compute composite scores of the study variables, which allows for the examination of fewer outcomes and the resultant management of experimentwise error. Planned analyses include analysis of variance for a series of 2 × 3 (site by treatment arm) comparisons to examine the extent to which the within-site randomization was successful, comparison of the two communities investigated in terms of demographics such as socioeconomic indicators and voting rates, improvement of participants in the various arms, linear mixed model regression analyses to examine the role of individual and community differences in influencing outcomes, and structural equation modeling analyses to examine paths of improvement and mediating and moderating variables associated with improvement.

Results

Sample characteristics

To date, recruitment and follow-up assessment of all participants is complete. Demographic characteristics are shown in Table 2. Of note, of the 292 participants, 86% were unemployed and 57% had never been married. Levels of general functioning (GAF: DSM-IV-TR) ranged from 21 to 85 at baseline, with a mean level of 46 (SD = 10.6) indicating moderate impairment.

Table 2.

Baseline demographic characteristics

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 43.5 ±10.4 | |

| Highest grade completed | 10.9 ±3.0 | |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 151 (51.7) | |

| Women | 141 (48.3) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| African American | 164(56.2) | |

| Latino | 102 (34.9) | |

| Mixed | 17(5.8) | |

| Other | 9(3.1) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 29 (9.9) | |

| Widowed | 12(4.1) | |

| Separated | 26 (8.9) | |

| Divorced | 57(19.5) | |

| Never married | 168(57.5) | |

| Employment status | ||

| Not employed | 252 (86.3) | |

| Employed part time | 35 (12.0) | |

| Employed full time | 4(1.4) |

Recruitment

Our initial recruitment approach, to identify participants through referral by their treating clinician, proved difficult and problematic. Clinical staff often referred those clients who they thought would ‘do well’ in the study, that is, participate and attend the designated study interventions. In fact, the interventions were geared toward people who were most difficult to engage and least involved in their communities, those that clinical staff was reluctant to include. To minimize this type of selection bias and to examine the utility of peer involvement, we began a supplemental recruitment method where peer staff members were available in the lobbies or other public areas of the mental health center with information about the study, and to whom people could provide permission for research staff to determine their eligibility through follow-up with their clinician. This strategy increased recruitment rates and helped to involve people more representative of the target population that clinical staff was reluctant to refer. Informal feedback from participants suggests that they appreciated being able to discuss their questions and concerns with peers who shared similar life experiences before agreeing to participate in the trial.

Lessons learned

In the following section, we discuss a number of lessons learned regarding the ‘process’ issues involved in implementing a set of interventions that could be standardized for methodological purposes while still remaining flexible and person centered in keeping with the aims of our research. These lessons were not derived from formal qualitative methods but rather from a review of extensive anecdotal reports from participants and staff. These reports had been discussed at length and documented in weekly project meetings throughout the implementation phase of the research. The validity of these lessons therefore is limited by their anecdotal source, and we limit our presentation of lessons learned to only the themes that surfaced repeatedly across staff and participants.

Many participants found that the 6-month intervention period was not sufficient time to establish and build a strong and trusting relationship with their primary peer supporter. They often expressed interest in expanding their involvement in the last 1–2 months of the study as the intervention was drawing to a close. Further complicating this picture was the fact that a number of the study’s peer staff also worked in other part-time peer-based roles at the participating centers. This ambiguity made it difficult to control the ‘ending’ of the formal intervention period and led to methodological concerns as participants could have more extended contact with peers in their ongoing routine service settings. Peers were offered significant up-front training in the principles and practices of person-centered recovery planning and how to encourage the implementation of PCP through their mentoring supports. Both clinical staff and participant response to the interventions over time prompted us to modify and/or expand the training curriculum and supervision to more thoroughly address the group dynamics and the potential tensions that may arise with the introduction of the peer mentor into the participants’ lives and the primary patient–provider relationships. We found that some of our most skilled and assertive peer staff required additional training in the ‘art of diplomacy’ when acting as an advocate during treatment planning meetings. This training was necessary in order to foster a productive team dynamic where the mentor would be perceived as a helpful supplement rather than as an external threat or critic. Peer staff (both PCP mentors and community connectors) also found it difficult to set their own limits at times when participants’ pushed them to deliver beyond what could reasonably be expected of the staff member in his/her role on the project. This aspect of the intervention proved to be a complex issue, which contributed to role confusion among staff as the frequency, intensity, and type of contact between peers and participants intentionally was not prescribed in keeping with the person-centered nature of the study and our understanding of best practice peer support.

Further clouding this role confusion was the difficulty we experienced in retaining distinct activities across the two intervention arms. We intentionally had designed these interventions to be delivered by separate peer staff for methodological purposes and our desire to maintain simplicity in the experimental interventions. However, both participants and peer staff expressed a preference to have supports delivered in a continuous manner by the primary person with whom they had formed a relationship. The ability to respect personal treatment preferences while also maintaining methodological rigor was just one of the many ethical challenges the research team faced throughout the course of implementation. The discussion of such challenges is beyond the scope of this article and warrants attention unto itself in future publications.

Although the parameters of the mentoring interventions allowed for some flexibility, they were clear in the objective of not inadvertently shifting dependence on the professional treatment system to dependence on a peer provider. This restriction of objective further complicated the roles of the peer staff, as some felt a sense of duty to go ‘above and beyond’ based on their own personalities or desire to ‘give back’ having themselves greatly benefited from peer support in their own illness and recovery. Although this held true for staff in both intervention arms, it was a particular issue for mentors, who by study design, were limited to a focus on treatment planning preparation and mentoring and explicitly discouraged from providing the in vivo community-based supports that characterize the Arm 3 Community Connector intervention. Each of these areas of complexity required significant ongoing training and supervision with the peer staff so that the interventions could be attractive and responsive to participant need while also remaining as methodologically rigorous as possible and respecting the limits and personal wellness of peer staff.

Finally, the need for cultural modifications around both the design of peer-based interventions and the training needs of staff represented an important lesson learned in the implementation of the study. Peer staff required additional competency building to respond to the diversity of multicultural issues (i.e., looking beyond race and ethnicity to consider age, gender, sexual orientation, etc.) and how these issues may impact participant and clinician response to the mentoring intervention. For example, we found that many Latinos were initially protective of their clinicians as they interpreted the novel role of the mentor as a potential intrusion on the primary clinician–patient dyad as this relationship was considered both highly valued and personal. Reports of peer staff also indicated that Latinos were more difficult to engage in the community integration activities compared to their African American counterparts as many Latinos expressed already having well-developed community and social networks and felt less need for support in this area.

Discussion

Despite the increased attention to recovery-oriented systems change as a result of national reports and transformation efforts, there is limited guidance for clinical practitioners regarding the translation of recovery concepts into concrete everyday practices. Existing guidelines often describe recovery-oriented supports that are independent of the formal clinical treatment system or that have been based largely on theoretical positions, first-person narratives, and the experience of multiple system stakeholders including persons in recovery, administrators, and service providers [4,80]. Although these are valuable knowledge sources, efforts would benefit from an enhanced empirical evidence base demonstrating the impact of recovery-oriented supports on both clinical and QOL outcomes. Our randomized controlled trial tests the efficacy of peer-supported, person-centered treatment planning and community-based rehabilitation for people of color with serious mental illness.

The findings of the present study will provide much needed information about the translation of recovery concepts into the routine practice of clinical treatment planning. Findings are expected to identify which specific key practices of person-centered treatment planning (e.g., providing a copy of the plan to the participant, having the support of a peer facilitator, enrolling natural supporters, etc.) have the greatest impact on treatment and QOL outcomes. Information gained from the study may be used to inform a wide range of clinical and administrative decisions within the public mental health system and aide state and national recovery-oriented transformation efforts.

This study has been designed to address many of the limitations of previous research on recovery-oriented practice and systems change as one of the common criticisms is that ‘recovery’ practice does not lend itself readily to being operationalized to concrete practice. Several methodological issues are acknowledged. The use of persons in recovery as peer supporters in the intervention arms was complicated by pre-existing relationships outside of the 6-month time period of intervention. In addition, the use of self-report data to measure psychosocial factors and perceived benefit of study interventions may contain bias (e.g., intentional or unintentional distortions, reluctance to comment critically on the peer-based intervention). Despite these limitations, we believe the current study will provide much needed information about PCP and peer-provided support.

Conclusions

Findings from this study should provide needed insights into the potential impact of person-centered treatment planning on clinical, recovery, and QOL outcomes. Data from this study will offer guidance to mental health systems seeking concrete practice change that will positively impact the lives of persons living with serious mental illness.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number R01 MH067687–01-A2) and is registered with clinical-trials.gov (identifier NCT0023193).

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity – A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General, Rockville, MD, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health, Rockville, MD, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.A practical guide for implementing the recommended national standards for culturally and linguistically appropriate services in healthcare. [homepage on the Internet]. 2001. Available at: http://www.omhrc.gov/clas/guide3a.asp (accessed on 7 September 2009).

- 4.Tondora J, Pocklington S, Gregory Gorges A, et al. Implementation of person-centered care and planning: how philosophy can inform practice. Unpublished paper, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine (IOM). Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerteis M, Edgman-Levitan L, Daley Jl, Delbanco TL. Medicine and health from the patient’s perspective In Gerteis M, Edgman-Levitan L, Daley Jl, Delbanco TL. (eds). Through the Patient’s Eyes. Jossey-Bass, Inc., San Francisco, CA, 1993, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Brien J, Lovett H. Finding a Way Toward Everyday Lives: The Contribution of Person Centered Planning. Pennsylvania Office of Mental Retardation, Harrisburg, PA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Brien C, O’Brien J. The Origins of Person-Centered Planning: A Community of Practice Perspective. Responsive Systems Associates, Inc., Syracuse, NY, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rapp C The strengths model of case management: results from twelve demonstrations. Psychosoc Rehabil J 1989; 13: 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vandiver BJ. Psychological nigrescence revisited: introduction and overview. J Multicult Couns Devel 2001; 29: 165. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casas JM, Pytluk SD. Hispanic identity development: implications for research and practice In Ponterotto JG, Casas JM, Suzuki LA, et al. (eds). Handbook of Multicultural Counseling. Sage Publications, Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA, 1995, pp. 155–80. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pope-Davis DB, Liu WM, Ledesma-Jones S, Nevitt J. African American acculturation and black racial identity: a preliminary investigation. J Multicult Couns Devel 2000; 28: 98–112. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strauss JS, Carpenter W. The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia, II. Relationships between predictor and outcome variables: a report from the WHO international pilot study of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974; 31: 37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carpenter WT, Kirkpatrick B. The heterogeneity of the long-term course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1988; 14: 645–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson L, McGlashan TH. The varied outcomes of schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry 1997; 42: 34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGlashan TH. Early detection and intervention of schizophrenia: rationale and research. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 172: 3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mueser KT, Meyer PS, Penn DL, et al. The illness management and recovery program: rationale, development, and preliminary findings. Schizophr Bull 2006; 32: S32–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drake RE, Mueser KT. Psychosocial approaches to dual diagnosis. Schizophr Bull 2000; 26: 105–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marrone J, Hoff D, Helm DT. Person-centered planning for the millennium: we’re old enough to remember when PCP was just a drug. J Vocat Rehabil 1997; 8: 285–97. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davidson L, Chinman M, Kloos B, et al. Peer support among individuals with severe mental illness: a review of the evidence. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 1999; 6: 165–87. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magura S, Cleland C, Vogel H, et al. Effects of dual focus mutual aid on self-efficacy for recovery and quality of life. Adm Policy Ment Health & Ment Health Serv Res 2007; 34: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowe M, Bellamy C, Baranoski M, et al. A peer-support, group intervention to reduce substance use and criminality among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2007; 58: 955–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hebert M, Rosenheck R, Drebing C, et al. Integrating peer support initiatives in a large healthcare organization. Psychol Serv 2008; 5: 216–27. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Felton C, Stastny P, Shern D, et al. Consumers as peer specialists on intensive case management teams: impact on client outcomes. Psychiatr Serv 1995; 46: 1037–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davidson L, Chinman M, Sells D, Rowe M. Peer support among adults with serious mental illness: a report from the field. Schizophr Bull 2006; 32: 443–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellamy CD, Garvin C, MacFarlane P, et al. An analysis of groups in consumer-centered programs. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil 2006; 9: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young AS, Chinman M, Forquer SL, et al. Use of a consumer-led intervention to improve provider competencies. Psychiatr Serv 2005; 56: 967–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chinman M, Rosenheck R, Lam J, Davidson L. Comparing consumer and nonconsumer provided case management services for homeless persons with serious mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis 2000; 188: 446–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlson LS, Rapp CA, McDiarmid D. Hiring consumer-providers: barriers and alternative solutions. Community Ment Health J 2001; 37: 199–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sells D, Davidson L, Jewell C, et al. The treatment relationship in peer-based and regular case management services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2006; 57: 1179–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clarke GN, Herincks HA, Kinney RF, et al. Psychiatric hospitalizations, arrests, emergency room visits, and homelessness of clients with serious and persistent mental illness: findings from a randomized trial of two ACT programs vs. usual care. Ment Health Serv Res 2000; 2: 155–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rowe M, Bellamy C, Baranoski M, et al. A peer-support, group intervention to reduce substance use and criminality among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2007; 58: 955–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mead S, Hilton D, Curtis L. Peer support: a theoretical perspective. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2001; 25: 134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salzer MS, Shear SL. Identifying consumer-provider benefits in evaluations of consumer-delivered services. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2002; 25: 281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Besio SW, Mahler J. Benefits and challenges of using consumer staff in supported housing services. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1993; 44: 490–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moxley PD, Mowbray CT. Consumers as Providers in Psychiatric Rehabilitation. International Association of Psychosocial Rehabilitation Services, Columbia, MD, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campbell S. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research. Rand McNally, Chicago, IL, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torrey WC, Drake RE, Dixon L, et al. Implementing evidence-based practices for persons with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatr Serv 2001; 52: 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stayner D, Davidson L, Tebes JK. Supported partnerships: a pathway to community life for persons with serious psychiatric disabilities. Community Psychologist 1996; 29: 14–7. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davidson L, Shahar G, Stayner DA, et al. Supported socialization for people with psychiatric disabilities: lessons from a randomized controlled trial. J Community Psychol 2004; 32: 453–77. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cook JA, Razzano L. Vocational rehabilitation for persons with schizophrenia: recent research and implications for practice. Schizophr Bull 2000; 26: 87–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Becker D, Drake R. Individual placement and support: a community mental health center approach to vocational rehabilitation. Community Ment Health J 1994; 30: 193–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mowbray CT, Collins M, Bybee D. Supported education for individuals with psychiatric disabilities: long-term outcomes from an experimental study. Soc Work Res 1999; 23: 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collins ME, Bybee D, Mowbray CT. Effectiveness of supported education for individuals with psychiatric disabilities: results from an experimental study. Community Ment Health J 1998; 34: 595–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDiarmid D, Rapp C, Ratzlaff S. Design and initial results from a supported education initiative: the kansas consumer as provider program. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2005; 29: 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bell MD, Bryson G. Work rehabilitation in schizophrenia: does cognitive impairment limit improvement? Schizophr Bull 2001; 27: 269–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wexler BE, Bell MD. Cognitive remediation and vocational rehabilitation for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2005; 31: 931–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drake RE, Becker DR, Bond GR. Recent research on vocational rehabilitation for persons with severe mental illness. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2003; 16: 451–5. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown MA, Ridgway P, Anthony WA, Rogers ES. Comparison of outcomes for clients seeking and assigned to supported housing services. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1991; 42: 1150–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rog DJ. The evidence on supported housing. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2004; 27: 334–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bellack AS. Skills training for people with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2004; 27: 375–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davidson L, Roe D. Recovery from versus recovery in serious mental illness: one strategy for lessening confusion plaguing recovery. J Ment Health 2007; 16: 459–70. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tondora J, O’Connell MJ. The treatment planning questionnaire assessing person-centered aspects of service and treatment planning. Unpublished measure, Yale Program for Recovery and Community Health, New Haven, CT, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 54.McMillan DW, Chavis DM. Sense of community: a definition and theory. J Community Psychol 1986; 14: 6–23. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chavis DM, Newbrough JR. The meaning of ‘community’ in community psychology. J Community Psychol 1986; 14: 335–40. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Costa PTJ, McCrae RR. Stability and change in personality assessment: the revised NEO personality inventory in the year 2000. J Pers Assess 1997; 68: 86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oyserman D, Saltz E. Competence, delinquency, and attempts to attain possible selves. J Pers Soc Psychol 1993; 65: 360–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oyserman D The lens of personhood: viewing the self and others in a multicultural society. J Pers Soc Psychol 1993; 65: 993–1009. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oyserman D, Bybee D, Terry K, HartJohnson T. Possible selves as roadmaps. J Res Pers 2004; 38: 130–49. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Phinney JS. The multigroup ethnic identity measure: a new scale for use with diverse groups. J Adolesc Res 1992; 7: 156–76. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Malcarne VL, Chavira DA, Fernandez S, Liu P. The scale of ethnic experience: development and psychometric properties. J Pers Assess 2006; 86: 150–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Utsey SO, Adams EP, Bolden M. Development and initial validation of the Africultural coping systems inventory. J Black Psychol 2000; 26: 194–215. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med 1997; 4: 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hatcher RL, Gillaspy JA. Development and validation of a revised short version of the working alliance inventory. Psychother Res 2006; 16: 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Williams G, Freedman Z, Deci E. Supporting autonomy to motivate patients with diabetes for glucose control. Diabetes Care 1998; 21: 1644–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.O’Connell M, Tondora J, Croog G, et al. From rhetoric to routine: assessing perceptions of recovery-oriented practices in a state mental health and addiction system. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2005; 28: 378–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Green H, Fletcher L. Social Capital Harmonised Question Set: A Guide to Questions for Use in the Measurement of Social Capital. Social and Vital Statistics Division, Office for National Statistics, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wowra SA, McCarter R. Validation of the empowerment scale with an outpatient mental health population. Psychiatr Serv 1999; 50: 959–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Babyak MA, Snyder CR, Yoshinobu L. Psychometric properties of the hope scale: a confirmatory factor analysis. J Res Pers 1993; 27: 154–69. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, et al. The will and the ways: development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. J Pers Soc Psychol 1991; 60: 570–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brookings JB, Bolton B. Confirmatory factor analysis of the interpersonal support evaluation list. Am J Community Psychol 1988; 16: 137–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cohen S, Hoberman HM. Positive events and social supports as buffers of life change stress. J Appl Soc Psychol 1983; 13: 99–125. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rosenberg M Conceiving the Self. Basic Books, New York, NY, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nguyen TD, Attkisson CC, Stegner BL. Assessment of patient satisfaction: development and refinement of a service evaluation questionnaire. Eval Program Plann 1983; 6: 299–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lehman AF. A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Eval Program Plann 1988; 11: 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Derogatis LR, Rickels K, Rock AF. The SCL-90 and the MMPI: a step in the validation of a new self-report scale. Br J Psychiatry 1976; 128: 280–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody G, O’Brien CP. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the addiction severity index. J Nerv Ment Dis 1980; 268: 26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McLellan AT. New data from the addiction severity index: reliability and validity in three centers. J Nerv Ment Dis 1985; 173: 412–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hall RCW. Global assessment of functioning: a modified scale. Psychosomatics 1995; 36: 267–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tondora J, Davidson L. Practice Guidelines for Recovery-Oriented Behavioral Health Care. Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, Hartford, CT, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Anthony WA, Cohen MR, Farkas MD. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Sargent College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Boston University, Boston, MA, 2002. [Google Scholar]